4

Competitive Advantage

From the moment you are born to your last day, it is a perpetual struggle to gain the upper hand and crush your enemies

Sun Tzu, The Art of War

In Chapter 3 we found that industry mattered for both investors and managers in terms of the returns that can be made, i.e. different industries make different returns.1 However, in most industries some organisations seem to consistently outperform their rivals in generating value for shareholders. Over the 10 years 1998–2008, incorporating just the start of the Global Financial Crisis, those who invested in GM and Ford at the beginning of that decade saw average annual losses of 22.3% and 21.2% respectively (i.e. from 1998 their total investment, including reinvested dividends, diminished on average by one fifth each year for 10 years). On the other hand, those who had the luck or foresight to invest in Oshkosh, a manufacturer in the very same industry, would have been far happier. They made average annual gains of 5.9%.

Why is it then that some organisations, in the same industry, consistently perform better or worse than others? Some of the answers to this question lie in an understanding of competitive advantage and competitive strategy.

Competitive Advantage

Industry rivalry benefits customers and consumers but harms industry profitability as marketing/development/etc. costs go up, and/or selling prices come down (see industry life cycle discussion in Chapter 3). All organisations, with the exception of monopolies, must compete with other organisations for customers. Even not-for-profit organisations increasingly must compete for the hearts and minds of the communities within which they operate by showing how they create a value that is greater than the alternative means of providing similar products, services or experiences.

An organisation with a competitive advantage can create and deliver better benefits to consumers than their competitors and simultaneously earn higher profits than the average of other organisations competing in the same market. Competitive advantage is the unique position that an organisation occupies in an industry and this is supported by distinctive resources and capabilities that are discussed in Chapter 5. Ideally organisations aim for sustainable competitive advantage, rather than short-lived positions (although in a few industries evolution is so fast that short-lived advantages may be the only way forward), so that they can consistently outperform their competitors in their chosen strategic outcomes. In industry terms (as we saw in Chapter 3), competitive advantage means that an organisation exploits market

Michael Porter argues there are two generic forms of sustainable competitive advantage:

- Cost advantage: an organisation can do the same things as its rivals but do so at a lower delivered cost, i.e. total costs – not just product/service costs. Such organisations exploit economies of scale, scope and learning (or experience) effects and are obsessed with efficiency and cost control.

- Differentiation advantage: an organisation offers something of value that is unique or sufficiently better than rivals to be seen as unique. These organisations create a form of monopoly in that nobody else can deliver the same product/service-based value to the target market. Their obsessions centre on protecting and improving their uniqueness in brand, product, process etc.

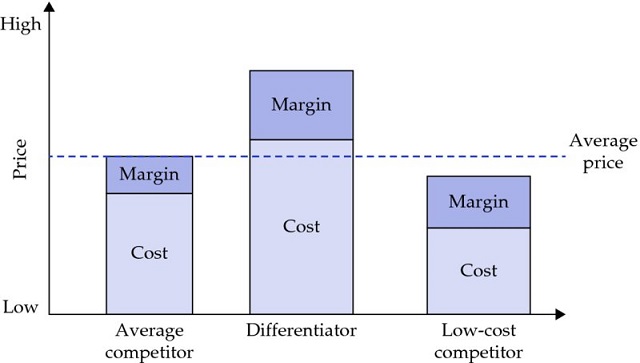

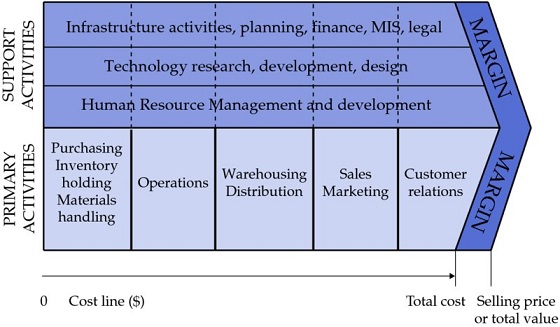

Figure 4.1 shows the profit potential of either of these positions. The differentiator competitor prices its products and services much higher than the average organisation and also has higher costs, but is able to realise a larger margin to reflect the value it is adding to the consumer. The low-cost competitor is able to price lower than the average organisation as it has lower costs and still achieves a higher margin. The low-cost competitor also has the option to increase its price close to the average competitor which may seriously erode the latter’s profits.

Figure 4.1 Cost and differentiation advantages

Although exceptions may exist, we can state the general facts that:

- Organisations with competitive advantage are more profitable, or create more value, than their rivals

- Organisations that consistently demonstrate higher profitability or value than rivals have competitive advantage(s)

- Organisations may be very good but may not be better than the others with which they are competing; consequently, many organisations do not have competitive advantage

- The degree to which an organisation can achieve competitive advantage is constrained, to some extent, by the dynamics of its industry.

Competitive Strategy

Competitive advantage is a measure of the relative superiority of a few organisations over others, whereas competitive strategy comprises the ongoing decisions or actions that each organisation undertakes to achieve its goals, a major one of which is competitive advantage. Definitions of strategy are legion and rather than attempt to re-invent the already re-invented we will stick with the non-controversial and classic definition by Alfred Chandler for the purposes of this chapter. This is that strategy is:

… the determination of the long-run goals and objectives of an enterprise, and the adoption of courses of action and the allocation of resources necessary for carrying out these goals.

Such strategies generally manifest themselves in the position an organisation adopts in terms of its stance relative to its competitors (be they other organisations in a for-profit arena or alternative investments of time, money etc. by key stakeholders in a not-for-profit arena), its products or services and its choice of buyer segments. This incorporates the broad value proposition that the organisation is offering compared to rivals and the customers to whom the value is offered.

An organisation with a competitive strategy should be able to describe its business model (see Chapter 6, Business Model Advantage) or the expression of how it adds value, using either or both of these two approaches. We explore them further in the paragraphs that follow.

Strategy as Positioning (or “Fit”)

As industries grow and evolve, the requirements for strategic success (i.e. Critical Success Factors or CSFs) also change. Each organisation, in order to survive, must (a) ensure a fit between its strategy and the CSFs of the industry, and (b) strive for competitive advantage over rivals who are also striving for the same thing.2 In this sense, all organisations have a strategy – whether this is a formally designed set of goals and plans or an unspoken consistency in a stream of decisions/actions does not really matter. However, as indicated above, only a few organisations have competitive advantage(s).

The Generic Strategy Matrix

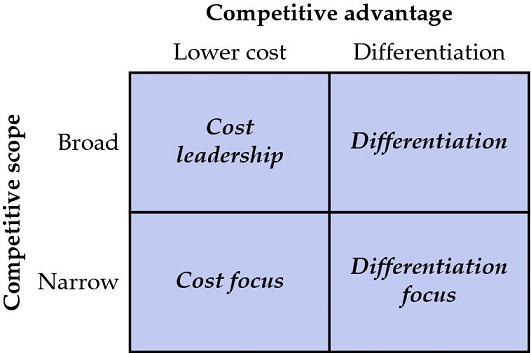

Unfortunately the traditional use of the same generic terminology (e.g. cost and differentiation) to describe both advantage and strategy can lead to confusion.3 We can see how this can happen by looking at the most commonly used strategic positioning framework, Michael Porter’s Generic Strategy Matrix (GSM), where strategic choices between cost and differentiation (which Porter labels the Competitive Advantage axis) are combined with a choice about the scope of attack: whether to compete across a broad front (a wide range or target market), or focus firepower on a particular segment or niche. This creates the four generic strategy categories that can be seen in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 Generic competitive strategies )

(Source: adapted from Michael E. Porter (1985) Competitive Advantage (New York: The Free Press)

This confusion between advantage and strategy here is potentially damaging to your wealth as the differences between generic strategies and advantages are critical. Strategic advantages protect the organisation against rivals and reduce the power of buyers/suppliers and the threat of entry and substitution – generic strategies, per se, may not. So, simply placing a company or a brand in a category (e.g. GM with its focus on scaled in cost leadership; BMW with its focus on broadening the appeal of its engineering innovations in differentiation; Land Rover with it narrow range and market segments in differentiation focus; and Hyundai with its small range and generally lower prices in cost focus) does not mean that it has a competitive advantage by being in that box. Hence it is dangerous to assume that because your strategy will place you in one category or another your organisation will be okay. Other factors will dictate whether that strategy confers an advantage in an industry. For example, historical factor conditions and a string of poor investment decisions mean that GM in 2009 certainly did not have a competitive advantage. Whereas Hyundai’s home conditions in Korea, aligned with their skill in deploying their low-cost strategy, combined with how this nicely “fits” with an increased sense of frugality in times of global financial crisis, would indicate that Hyundai at that point in time did have a competitive advantage.

One of the strengths of the GSM is its simplicity. This makes it a useful starting point for discussions about strategy, positioning and advantage. However, simplicity can be a weakness too, and it can blind users to alternative options. It can be helpful, therefore, to also think about positioning in relation to other complementary frameworks. We describe different frames below.

Four different scope strategies

In a more detailed description of the competitive scope dimension depicted in the GSM, Henry Mintzberg4 suggests there are four generic approaches:

- Unsegmentation: the organisation offers the same products across a broad range of market segments, e.g. Coca-Cola, Wal-Mart, Google

- Segmentation: the organisation still addresses a broad range of market segments but designs different products for those segments, e.g. Honda, Dell, British Airways

- Niche: the organisation focuses on one segment of the market, e.g. Ryanair, LVMH Group, Mothercare

- Customisation: the organisation focuses on individual customers and shapes their offering to the unique requirements of that buyer, e.g. upmarket homes, event organisation, golf course design.

The strategic “clock”

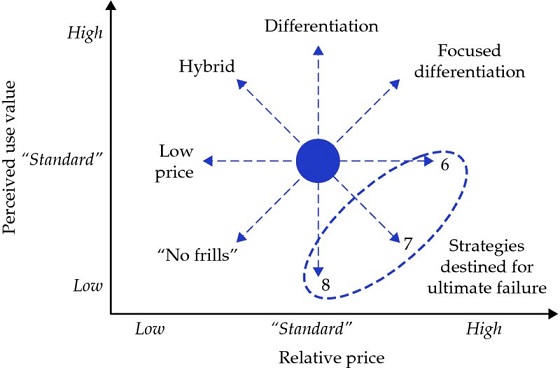

Within a strategic group, Michael Porter’s Generic Strategy Matrix suggests that there are still low-cost and differentiation positions – termed cost focus and differentiation focus – and that whether competing on focus or across the whole market, it is a major problem for any company to be “stuck in the middle”, with neither sufficient differentiation advantage to claim a price premium or guarantee customer loyalty, nor sufficient cost advantage to underpin superior margins at prevailing prices. However, other authors are not so sure that this is such an either/or choice and point to the success of Japanese car organisations such as Toyota or Honda in offering high-quality, highly and flexibly featured vehicles produced at low cost with substantial brand equity. Another generic strategy framework that does acknowledge the possibility of a high-value/low-cost strategy is the strategic clock (Figure 4.3). This suggests that viable strategy options depend on how the organisation’s offering is perceived by the market in terms of its price relative to other offerings and its relative perceived use value. Whereas a low-price strategy offers a standard perceived use value at a low price, a differentiation strategy offers a high perceived use value at a standard price.

Figure 4.3 The strategic clock

(Source: Cliff Bowman (1988) Strategy in Practice (Harlow: Prentice Hall))

The strategic clock5 goes further, however, and acknowledges the viability of the high-value/low-price “hybrid” (e.g. the Japanese car manufacturers on entry to the US or Tesco as in the case in this book); high-value/high-price “focused differentiator” (e.g. luxury goods); and low-value/low-price “no-frills” (e.g. low-cost airlines) strategic options. Both the no-frills and the focused differentiator options are consistent with Porter’s focus quadrants. As with the GSM, the differentiators can leverage their differentiation through price premiums or increased volumes/market share. Those operating in the low-price arena will tend to experience price wars that will put pressure on margins and encourage cost reductions that will push them towards the no-frills segment. The remorseless pressure of imitation and competition, meanwhile, will tend to pull the hybrids into the competitive orbit of the differentiators.

According to the strategic clock, the strategies that are doomed to ultimate failure are those where the offering ends up being perceived to have low relative use value but standard or higher relative price. Marlboro (cigarettes), Compaq (computers) and Kodak (photofilm) were able to maintain high relative prices over a long period but as they fell out of fit with the wider environment, their perceived relative “use value” declined. They ended up in the lower right-hand quadrant of the strategic clock and sales fell accordingly. In competitive markets, significant price decreases were needed to save them from a niche existence. However, in markets where an organisation is in a monopoly position, or is able to lock in customers, it is entirely possible for them to have a sustainable strategy that is characterised by high price and low perceived user value.

Six different differentiation strategies

You will have noticed that the strategic clock has made a subtle but significant reorientation to price as an advantage rather than cost (it is important in strategy to remember that these are not the same or necessarily even related – think about how Nike, for example, succeeded for many years with a low-cost, high-price strategy). Another framework by Henry Mintzberg endorses this stance in suggesting that all strategy and advantage is based on some form of differentiation of which price is one variant. It takes Porter’s simple differentiation column on the GSM and suggests six different forms of differentiation strategy (Table 4.1). Any of these may or may not lead to sustainable competitive advantage depending on (a) the value the customer places on the chosen option, and (b) how much better the organisation is than its rivals in delivering this option.

Table 4.1 Six basic differentiation strategies

| Strategy | Description |

| Low price | A lower price than rivals, e.g. the no-frills airlines versus the big national carriers in the US and Europe |

| Image | A brand or reputation, e.g. Coca-Cola, Mercedes, Gucci, Harvard Business School etc. |

| Support | Provision of back-up or after-sales service, e.g. Dell |

| Quality | A more durable or reliable product or one with higher performance, e.g. digital cameras (pixels) |

| Design | Different product functions, e.g. pharmaceuticals, mobile phones |

| Undifferentiation | Same as the others, e.g. car rental organisations, financial service organisations, petrol stations, steel businesses etc. |

Source: adapted from Mintzberg, 1998

A useful insight from these six options is the fact that many organisations basically do the same as each other – they are undifferentiated. They offer similar products at similar prices with similar service etc. and still make enough money to earn an acceptable return on invested capital (ROIC) – just how differentiated is one financial services institution from another, for example? Note that whether a strategy is actually undifferentiated or not may depend on who you ask – most if not all organisations are trying to adopt a different position. The less differentiated they actually are, the greater their need for “gaming” to improve their strategic position.

Gaming for position

When there are very few competitors (as, for example, in an oligopolistic industry), or many undifferentiated competitors, strategic moves must explicitly take into account the potential (and likely) responses of rivals. Game theory6 is that branch of economics/strategy that analyses decision processes and outcomes when each actor makes decisions – for example, pricing, capacity, product introduction – based on the anticipated actions and reactions of its rivals. Delving into the full intricacies (and mathematics) of game theory is beyond the scope of this text but the following example gives a flavour of the sort of reasoning in a game theoretic decision.

Suppose that a capital-intensive industry, dominated by two main, equal-sized and not very differentiated organisations called Caesar and Brutus, has demand that exceeds current supply. The CEOs of Caesar and Brutus are contemplating expanding capacity but the nature of the manufacturing process is such that capacity can only be expanded in relatively large and expensive lumps. The CEO of Brutus has a financial model that shows her the following profit figures for her company depending on the expansion outcomes:

- No expansion by either – Brutus profit: US$360 million per year (i.e. maintaining current profits)

- Brutus expands and Caesar does not – Brutus profit: US$400 million per year

- Brutus does not expand but Caesar does – Brutus profit: US$300 million per year

- Both expand – Brutus profit: US$320 million per year.

But she knows that the CEO of Caesar has exactly the same set of figures for his company. So what to do?

John Nash (made popularly famous through the film A Beautiful Mind) won a Nobel Prize in economics for his analysis of such situations. His insights demonstrated why the most likely outcome in such cases is that both organisations expand (i.e. outcome 4 above, a worse outcome than Brutus doing nothing). One way to understand why this is so is to put yourself in the place of either CEO and answer this question: “Given you do not know what the other organisation will do, what is the decision you can make that you will never (financially) regret whatever your opposite number does?” You might also further understand why tacit or even explicit (generally illegal) collusion is so tempting in oligopolistic competition; and why it has become popular to develop “blue ocean” strategies (see below) – strategies that enable you to get clear of the bloody “red ocean”, where the undifferentiated pack is fighting it out at close-quarters.

Blue Ocean Strategies

Competitive strategy for most organisations means red ocean strategy – companies fighting tooth and nail in highly competitive, often mature, markets. The prospect of vicious endless bloody competition has prompted some of them to seek new territories in which to prosper. Organisations that are able to create “uncontested market space” may well benefit if there is new demand for their products and services. This requires organisations to think differently from the norm, to find new sources of differentiation and to perceive new market opportunities. For instance, organisations that did not fall into copycat traps associated with red oceans include:

- Anita Roddick’s Body Shop that went against traditional ways of how cosmetics are developed and sold. She challenged the industry’s previous assumptions and produced cosmetics that were about natural ingredients that would appeal to her customers’ concern for the environment. Through a combination of low-key marketing, consumer education and social activism, she created ethical consumerism that had massive impact.

- Cirque du Soleil was a Canadian circus troupe in a dying industry. It decided to collapse two industries into one: theatre and circus. This led to a new type of offering that did not have animals, invested heavily in high-quality performers and produced musical shows with themed storylines. This saw Cirque open up entire new venues and a new audience (who were prepared to pay higher prices) and today it is the largest theatrical producer in the world.

- Swatch challenged the assumption that a watch was a luxury or high-tech item that people only needed one of. It sold watches as collectable fashion accessories.

In these examples, there are start-ups with new ways of perceiving an industry (The Body Shop) and innovations to the previous way of thinking and operating (Cirque du Soleil and Swatch). Chapter 8 explores in more detail how organisations may embark on new ventures in order to find and benefit from new uncontested market spaces.

The term now used to describe the creation of new uncontested market spaces is blue ocean strategy. It was created by Kim and Mauborgne7 whose research shows that while 86% of organisation or product launches are line extensions, or incremental improvements, they only account for 62% of organisational revenue and 39% of profits. Value innovations (the remaining 14% of launches) account for 38% of revenue and 61% of profits. Their insight is related to the S-curve (see Chapter 3) that shows how a product will hit a plateau where further improvement will either be impossible or prohibitively expensive. Organisational performance over the long term thus requires new market spaces to be created for different products and services. For instance, the Swatch watch resulted from embattled Swiss watch manufacturers facing serious decline. They found themselves being forced to reconceive the market for watches or face collapse and so produced collectable fashion accessories, rather than just timepieces.

Kim and Mauborgne’s promotion of value innovation, as the technique for coming up with something new, is an approach that ensures that an organisation’s strategy focuses on providing added value to customers rather than just invention for the sake of it. Hence, the selling of books without bookstores, or nappies that are disposable, or flights that operate more like buses are as much “value innovations” as the smartphone. Kim and Mauborgne suggest that value innovation can be advanced by any manager asking structured questions such as:

-

What factors could be eliminated that an industry has taken for granted?

In banking, the question that the first internet bank, egg, asked was: do banks need branches? In the higher education sector, online providers question the need for the vast investments in real estate characteristic of most universities.

-

What product/service elements could be reduced below the industry standard?

In the airline industry, Southwest Airlines, Ryanair and easyJet all ask about the need for in-flight meals, paper tickets and luggage in the hold. More recently, low-cost carriers have been thinking that seats, windows and even pilots may not be necessary.

-

What elements could be lifted above the standard?

In the consumer electronics industry, Dyson asked whether mundane day-to-day objects, like vacuum cleaners and washing machines, could have designer styling.

-

What should be introduced that the industry has never offered the customer?

In the watch industry, Swatch’s idea was that you could launch watches like fashion collections. In the book retail industry, many bookshops have in-store cafes.

-

Could a new offering win buyers without any marketing hype?

The Smart car or BMW’s Mini created demand simply through people seeing them on the streets.

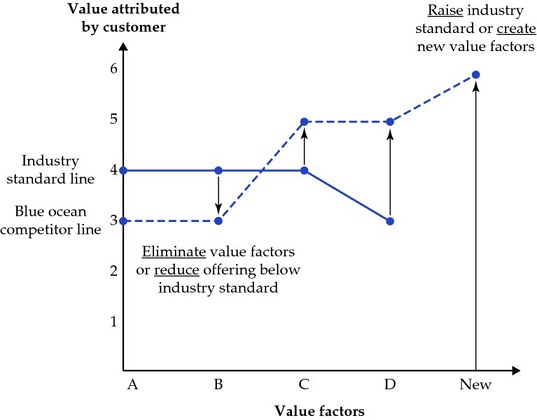

For an example of a blue ocean competitor, see Figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4 Blue ocean strategies

The main attraction of blue ocean strategy is that it allows an organisation to dominate the new territory and set the terms of engagement with the customer. Indeed, a smart blue ocean competitor will invest in barriers to entry to this new territory and this may cause it not only to differentiate by doing something differently, but also to keep its costs under control in order to reduce the incentive for other organisations to enter and undercut it. We see blue oceans then as pre-competitive markets, existing before other capable competitors invade the territory, increasing competition and again forcing organisations to choose between cost or differentiation positions.

However, there are risks to blue ocean strategy, not least that customers will not value the new territory. Even if they do, the organisations’ product/service offerings and value innovation will take time to pay off and may even fail.

Supporting Competitive Position

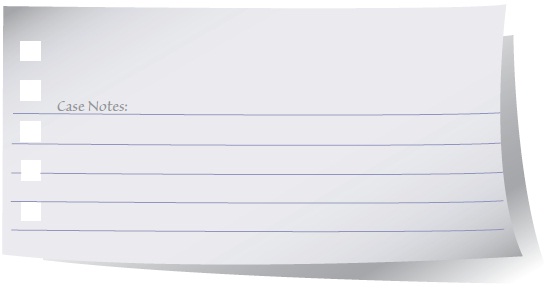

Industrial organisational theorists like Porter stress the importance of establishing a close fit between the strategy of the organisation and the critical success factors of the environment. This emphasis has tended to deflect attention away from the fact that establishing an advantageous position depends on performing competitively valuable activities better than rivals. Porter highlights this through the value chain (Figure 4.5).

Figure 4.5 The generic value chain

(Source: adapted from Michael E. Porter (1985), Competitive Advantage (New York: Free Press))

What the value chain does is to focus our attention on the underlying activities and capabilities that are the prime source of developing and maintaining an advantageous position in the market. This source will vary by organisation so that whether an activity is merely a (necessary) cost or a source of strategic value (advantage) varies between different organisations across different industries. Marketing (via branding and distribution) is the key value differentiator for Coca-Cola, and so is a focus on investment and development, whereas operations and outbound logistics, making and delivering the cola, are operations to be made as efficient and cost-effective as possible. For Federal Express, however, distribution and logistics comprise its core differentiated offering.

One need not respect the sections in the chain as Porter drew it. Many modern organisations don’t have purchasing or warehousing or inventory in the way that companies did in the 1980s when the value chain was first drawn (think of Google for instance). It is better to use the broad outline of the chain to express your organisation’s business model (see Chapter 6), thinking through and drawing the things it does to convert inputs into outputs of a market value greater than the cost of conversion. If an activity in the value chain is not a necessary cost, or does not add value greater than its cost, or the value added is low relative to other activities in the chain, then you should ask whether it is worth continuing with it. Maybe there is a case for outsourcing such an activity if a provider can achieve the same or better, reliably and at lower cost. This sort of thinking has driven a great deal of outsourcing in the financial services industries to low-wage economies such as India where there is also high-quality IS/IT capability. In Formula 1 motor racing, the Williams team outsources the parts of its racing cars, preferring to rely upon the world-class engineering skills of a wide variety of component suppliers rather than trying to be world-class at everything in-house. Williams’ contribution is providing a critical set of skills as a strategic assembler of components.

In some instances, it is preferable to keep an activity in-house as it is deemed strategic to the organisation as a whole. Keeping it in-house may be linked to protecting core capabilities and resources (of which more in the next chapter) and maintaining organisational flexibility. This is the thinking of Ferrari who prefer to carry out nearly all of its engineering in-house. Maintaining an activity may also be part of a loss-leader strategy, whereby you make a loss on one activity (e.g. Formula 1 racing) to promote value elsewhere in the organisation (e.g. the perception of a brand as “high performance”). Or it may be that you need to face up to a long-cherished activity becoming uneconomic!

So far, we have considered value chains as simple linear sequences with a question mark over which parts should be kept in-house and those that might be outsourced. However, many organisations have much more complex value chains than represented here so far. Organisations will have many products and services and may be competing in many markets (see Chapter 7 on Corporate Advantage). These may require quite different positioning strategies for advantage in those marketplaces. In order to take this additional complexity into account, Cummings and Angwin (2004)8 created a value chimera (see Figure 4.6). This takes the basic shape of the value chain but gives it many “heads” to depict a strategic reality for most organisations of any size with different “horses for courses”, or brands or products that will require different positioning strategies. It can be useful to think of how an organisation’s different product lines are positioned to meet different target markets on the right-hand side of the chimera (e.g. think about where the Volkswagen group’s Lamborghini, Audi, Seat, Skoda and VW might sit in the Generic Strategy Matrix) and then analyse how the organisation can allow resources and capabilities to be combined for cost savings earlier in the chimera so that the left-hand side can generate significant economies of scale. For strategists, the trick is to achieve competitive advantages in different marketplaces, scale economies among suppliers and manage tensions throughout the value chain in order to enable expertise to be transferred across different “horses”. Effective strategic positioning of the whole value chain should enable greater value to be created than the collective costs of running these many activities separately.

Figure 4.6 The value chimera as a way to link corporate and competitive strategy

At the beginning of the chapter we asked the question: why has Oskosh Truck been able to remain a star performer over a sustained period of time, while other organisations in the same industry have performed much worse? We can now see that such long-term superior profitability depends on how much better an organisation’s strategy fits with its industry forces relative to its rivals and its attention to developing and marshalling unique resources and capabilities to maintain and improve that position. We also know that others in the industry are attempting to wrest away Oskosh’s advantage, because that’s what happens in mature industries. On rare occasions, macro-shocks, in the form of significant technological advance (e.g. electricity, the telephone, the internet), batter down the existing advantages of incumbents but, in the main, advantages are slowly eroded by the prevailing winds of imitation and substitution.

In line with Sun Tzu’s quote at the beginning of the chapter, the driving quest of all organisational strategy must be to gain the upper hand and crush your enemies before they crush you. Finding and protecting a unique valuable position(s) in the market is key. However, being better than others at the same thing is highly unlikely to remain unique (advantageous) in the long term. It is critical for organisations to develop continuously to remain in optimal fit with their market(s) and the broader environment, and to protect and invest in sources of difference to avoid loss of competitive advantage.

Strategists must be paranoid – the competition are out to catch and overtake you. You must stay apart from the crowd!

Competitive Advantage Key Learnings Mind-Map

Having read and reviewed this chapter, outline what you believe to be the key learnings from the chapter and the relationships between these on the note pages below.

4-1 Tesco: The Train Pulling in is Tesco

In 1997, Tesco, the UK’s largest retailer and its biggest private employer, announced its intention to establish a 2,508 square-metre supermarket at the train station of the village of Gerrards Cross in the county of Buckinghamshire, southeast England. Gerrards Cross is an affluent village with a typical house price costing almost four times the national average. Most of the 7,342 villagers were horrified at the thought of a mass-market retail outlet and, citing concerns about increased traffic and the impact on local retailers, the district and county planning offices refused permission for the store to be established. Tesco management appealed that decision to the highest level of government. Their appeal was approved and, from November 2005, Tesco, with 2004 revenues of over £31bn, would become a big part of little Gerrards Cross.

On hearing of the success of the company’s appeal, the village greengrocer relet his property to a betting shop. He recognised what many had found out before – when Tesco comes to town, local food retailers leave. In 1950, there were over 260,000 independent grocery stores throughout the UK. Sixty years later that number was less than 40,000, with even some of these being Tesco outlets. The modern-day Tesco not only has over 30% share of the overall UK grocery market through its stores and online services, it also has significant presence in the petrol retail market and a growing position in a variety of other areas, including clothing, home goods and personal finance. Combining this with its growing international ventures in Europe, the USA and Asia makes Tesco an irresistible retail force.

Ironically, Tesco itself started as a very small store. Returning to his family home after serving as an air force mechanic in World War I, Jack Cohen, son of a Polish-Jewish tailor, made a living by selling cans of food from a market stall in London’s East End. He began by buying £30 of army surplus rations, taking them to the Well Street market, and selling them for a profit of £1. As well as army surplus food stocks, Cohen’s low-cost purchases included unlabelled tins from salvage merchants who had themselves bought the products as reject batches from large manufacturers. Cohen would relabel the dented cans and sell them on at very low prices to grateful customers living on tight post-war budgets; customers who could not afford the prices charged by the established “high street” retailers like J. Sainsbury and Marks & Spencer.

By 1930, Jack Cohen was operating a string of stalls across markets all over London and, such was his increased purchasing power and acumen, had become a wholesaler to other stall holders. The dubious sourcing strategies of some of their supply channels meant that he and his nephew still had to rebadge cans with new labels to disguise their brand origins. One day, needing a new label for a batch of tea, Cohen combined the first three letters of the supplier’s name with the first two letters of his surname and “Tesco” was born. He opened his first store in 1931. By taking advantage of the post-war housing boom outside London, and paying low rents to grateful developers, he had 100 stores by 1939. Tesco’s profits came from high-volume sales driven by low prices (“pile it high, sell it cheap”) based on Cohen’s obsession for low-cost inputs that included low employee wages. On a 1946 visit to America he found a mechanism that both increased throughput and reduced (employee) costs – self-service. Tesco stores became self-service “supermarkets”.

By the early 1960s, as J. Sainsbury opened lavish new premises that focused on offering well-presented quality products (at higher prices) to its middle-class customers, Tesco had expanded to over 400 outlets through the acquisition of cheap stores. In 1961, it opened a new-look store in Leicester combining food and non-food items and providing undercover parking for 1,000 cars. Its new format caused further clashes with the brand-name manufacturers. They had often taken the company to court for setting its own retail prices in defiance of the “resale price maintenance” laws under which the supplier set the retail prices. Tesco fought these laws and eventually, by one vote, the British Parliament struck them down; price wars were now legal between competing chains. Over the next decade they grew rapidly as thousands of small stores, stripped of price protection, closed throughout the country.

In the mid-1960s, Tesco increased sales further when it introduced “Green Shield Stamps”. Customers collected these, based on the value of their purchases, and traded them in for goods when they had collected the stipulated amount. Its up-market rival J. Sainsbury was disdainful of such inducements and campaigned unsuccessfully for their removal. In the 1970s, with Britain in the grip of national union action and the working week reduced to three days, Tesco sales and profits declined. In response, the company dispensed with stamps and slashed prices to reflect the £20m annual cost savings. The shoppers returned and sales surged ahead once more.

Throughout the next two decades, Tesco expanded its product range, store size and polished a new image as it wooed consumers, employees and local authorities. It introduced share incentive programmes for workers. Its small, crowded, untidy, “pile it high” stores were closed to make way for spacious, tidy supermarkets, hypermarkets and specialty shops catering for the increased affluence and mobility of its customer base. High-end brands shared shelf space with (cheaper) Tesco branded products across an increased range of products. This enabled the brand-conscious consumer to shop alongside her more price-sensitive companion. In 1995, Tesco overtook J. Sainsbury to become the largest retailer in Britain.

Tesco remains price competitive as it must but the reality is that all supermarket chains use their buying power to manage costs and so the actual price differences between the majors are minimal. In 2007, a trolley of 100 common items bought at Tesco for £173.97 cost just 74p less at Asda, a large but more down-market rival (data from The Grocer). Comparing bigger shopping baskets of 10,000 items yielded a similar result, with Asda and Tesco charging the same for almost three-quarters of their goods. What price differences exist in reality are too small to be noticed by most shoppers and hence it is perception that becomes critical, and here Tesco’s budget for branding (perception shaping) is much larger than that of any of its rivals.

Tesco is a classic “small to huge” success story and this deserves to be understood. However, since 2015 things have not gone so well, with growing competitive pressures from new entrants to the market such as Walmart and Amazon, a slow growth economy, failing overseas ventures in the US and China, an accounting scandal and falling share price. Meanwhile, competitors such as Sainsbury, facing many of the same issues, seem to have done well. How might this be explained?

Some suggestions

Some suggestions

Beginning in an era when many people suffered great financial hardship, Jack Cohen’s market stall sold damaged cans of food at very cheap prices. This is the ultimate in no-frills (strategic clock), cost-focus (Porter) or low-price (Mintzberg) strategies. His competitive advantage was based in low costs derived from his buying acumen (a capability) and his willingness to use (legally) dubious sources. In contrast, the more traditional high street retailers such as J. Sainsbury and Marks & Spencer were firmly in the category of broad-based differentiators offering quality of goods to underpin their higher prices. Even after the stall became “Tesco”, Cohen continued to focus on price rather than quality or product range as his main profit-generating approach. His stores were small, untidy and crowded with goods. In a sense, they were mini warehouses staffed by a few people to take customers’ money (and finally by even fewer people following the move to self-service).

The launch of “Green Shield” stamps was both a form of price discount (added value for the same price) and a mechanism for locking in customers who were tempted to add more and more points to gain higher-value “rewards”. While this value-adding ploy was in effect, Tesco still offered low prices and no-frills products/services. Dumping the stamps and slashing prices was Tesco’s last major initiative as a “no-frills” retailer.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Tesco’s consumers became increasingly affluent and less in need of lowest prices. They began to move up-market in their food and drink tastes and, while perhaps shopping for basics at the cheaper Tesco, began selectively purchasing higher-value items at J. Sainsbury and Marks & Spencer. Although strongly resisted by Cohen,9 Tesco began to follow its customers up-market as it moved from a no-frills to a low-cost (strategic clock) strategy (more broadly targeted cost advantage

Gradually Tesco crossed the major mobility barriers between its strategic group (the “pile it high and sell it cheap” retailers) and the “quality and service” strategic group made up of such stores as J. Sainsbury and Marks & Spencer. It did so by adding a perception of value without sacrificing the inducement of price. Its “strategy” emerged so gradually that its competitors did not notice the gradual erosion of the barriers.

Note that it is doubtful that Tesco management ever articulated a formal (design) plan to “take on” J. Sainsbury – they just followed their customers. The danger of an emergent strategy is that if even the company does not “know” that this strategy is in place the competitors may also remain ignorant and not respond until it is too late.

Tesco’s dominance and strategic strength emanated from its “hybrid” position on the strategic clock. On the one hand, it offered a wide range of branded and own brand products in modern, clean, efficient supermarkets with parking, facilities for children and other on-site specialist services, but it still offered (or at least appeared to offer) lower prices. It underpinned these low prices with low costs which it enjoyed because of its buying power. With many suppliers Tesco enjoys “monopsony” power in that it takes most (if not all) of the supplier’s product (readers are probably more familiar with the term “monopoly” which is where the supplier dominates the market). Note, however, that Tesco does not necessarily have the lowest costs but it certainly had at least low costs equal to its major competitors and much lower costs than its smaller rivals.

Tesco continues to grow into various other segments of consumer goods and as it grows so too does its relative buying power (its bargaining power) and its ability to differentiate itself through branding. Its latest initiative is to bid £3.7bn for Booker, the largest wholesale food provider in the UK that should allow it to gain further economies of scale and drive down its costs. Price is the key competitive weapon for broad-based retailers stocking the same goods. Any retailer with a structural cost advantage that offers the same (or better) perceived value as its competitors is a formidable contender. The Tesco train has been dominant for nearly two decades and only now may it begin to slow down.

![]()

4-2 IBB: Mirage?

In August 2004, the Financial Services Authority granted a banking licence allowing the Islamic Bank of Britain (IBB) to open its first retail branch in London, promoting sharia-compliant products. Islamic law (the sharia) bans the payment and acceptance of interest – fundamental concepts in Western banking. In early 2005, IBB opened a branch and head office in Birmingham, a lower-cost location than London, and one where a substantial proportion of the country’s Muslim population resides. Other branches followed in London and Leicester, with further branches planned for other areas of high Muslim concentration (www.islamic-bank.com). However, start-up costs on branches and direct banking widened losses to £3.1m in the first five months to December 2004. IBB is imprisoned by its fixed costs and has to grow to escape its constraints and compete with the huge cost-reducing scale economies of its giant conventional competitors. Is this quest to become the first fully fledged Islamic bank in the UK and Europe really chasing a mirage?

Muslims are the second largest religious group in Britain and, with 2 million followers, there is clearly a potential market for an Islamic bank. However, there are two problems facing IBB: (1) Muslims have historically avoided banks if they want to retain their beliefs; and (2) the Islamic banking model may not be competitive in the mature UK banking market.

Islamic beliefs

In Islam, human beings are God’s co-managers on earth and the well-being of the community must be considered when it comes to economic actions. Wealth should be neither hoarded nor wasted on unproductive ventures. Money should not be created from money, but through investment in useful activities. Interest is opposed on several grounds, but from a social perspective, it is the poor and needy who are forced to borrow whereas the rich have money to save. Interest therefore penalises the poor and rewards the rich. The accumulation of wealth through interest is deemed a reward without productive effort and is therefore selfish. On this basis, conventional banking is not appropriate for Muslims.

Islamic banking

The essential feature of Islamic finance is that it is interest-free. Sharia explicitly prohibits interest (riba) and excessive risk or uncertainty (gharar). The prohibition of interest does not mean that money may not be lent under Islamic law, it simply rules out what might be considered unearned profit. Indeed, the provider of capital should be allowed an adequate return by having a stake in the undertaking, but is not permitted to fix a predetermined rate of interest. Money is not considered a commodity in Islamic economics, but rather a bearer of risk. There should be a price for time, but not fixed in advance. Owners of capital can share the profits made by the entrepreneur based on a profit-sharing ratio rather than a predetermined rate of return. This means that the borrower and lender share risk and work more closely together to ensure the business’s success, which is more productive for society and provides cohesion between social classes because finance is available equally to anyone with a productive idea.

Two of the most popular types of “compliant” business in Islamic banking are: (1) murabahah, a contract for purchase and resale that allows customers to make purchases without having to take out loans and pay interest; and (2) mudarabah, an investment on your behalf by a more skilled person who shares part of the profits in return for time and effort (see case note below for further details).

IBB offers the following products to both Muslim and non-Muslim customers and stresses the fact that it tries to make all transactions with the bank simple for customers in terms of delivery and understanding:

- Current account – includes the same facilities as conventional current accounts but no interest is paid or charged and a credit balance preferred.

- Saving account – offers term structures and operates on a mudarabah basis, with the clients sharing in the bank’s profits, the rate being reviewed monthly.

- Treasury deposit account – for high-net-worth clients. The minimum deposit is £100,000, with fixed periods. Structured on a murabahah basis, the depositor obtains the profit from the purchase and sale of commodities.

- Masjid (mosque) proposition – a free overdraft of £1,000 to mosques for a maximum of 30 days. This is very successful because mosques are major influences on local communities. When Muslims see their mosques dealing with IBB, this boosts their confidence in the bank and its Islamic nature.

- Sweeping facility – transfers money automatically from the customers’ saving accounts to their current accounts to avoid the latter getting overdrawn.

- Other products – home finance, Islamic credit cards, internet banking in 2006. In the horizon of three to five years, the bank plans to introduce mobile banking, to offer investment and insurance products – possibly through the establishment of a UK subsidiary – and to establish physical continental European branches.

The banking market in the UK is highly consolidated, with the top six players accounting for 83% of the total market for financial retail services. The market grew at 10% (2002–3) and the banks have been posting record profits, aided by aggressive reduction in costs through the use of technology. At the same time, there has been a reduction in customer satisfaction in the level of service received.

Within the UK market of 65 million, there are over 2 million Muslims. Of these, 62% are drawn from the Indian subcontinent and 21% from the Middle East and Africa. There are high concentrations in urban areas, with half living in London, and this promotes strong social cohesion. Unemployment among Muslims is almost three times the national average and the quality of their housing is among the lowest in the country. The young and the old show strong religious devotion, with 250,000 attending mosques regularly. Although strongly influenced by British society and culture, the majority of the young are proud of their Muslim identity. Many Muslims have small businesses and an increasing proportion of young Muslims are joining the professional classes. The estimated pool of savings of Muslims in the UK was £1bn in 2003.

The recent spate of terrorist attacks has raised anti-Muslim sentiment in Britain. However, no Islamic bank has been linked in any way to these activities.

Interestingly, the effect upon Muslims has been to cause them to turn more to their religion, and Islamic banks in general have witnessed a huge surge in business when their links to terrorism were shown to be unfounded.

Competition for Muslims worldwide has been rising rapidly. Many of the key players in conventional banks, such as HSBC, now provide Islamic offerings targeted at institutional clients and overseas high-net-worth individuals, rather than Muslims in Britain. Other competition comes from the providers of ethical banking, such as the Co-operative Bank, and Islamic institutions operating in the UK as subsidiaries owned by offshore operators, such as Pakistani and Bangladeshi banks. These latter banks also provide reliable and trustworthy communications channels for British Muslims with families in the Indian subcontinent. However, this service may be more valuable to first generation immigrants rather than younger generations with weaker overseas ties. Also, these banks are limited in their product range, such as money transfer.

IBB feels the increasing competition may make customers more aware of this type of banking practice and help to sell the concept and “grow the cake”. However, they think these Islamic offerings are not really Islamic in either manner or essence of operations. For instance, HSBC Amanah in raising money can borrow this informally from the parent, which is a non-Islamic channel. From a conservative Islamic point of view, this money is tainted.

There is no doubt that IBB differs significantly from conventional banks:

- Although there are similar types of risk, they are run at higher levels because of extensive trade and investment activities. However, there is no interest-rate risk.

- Liquidity management is a problem owing to the lack of sharia-compliant liquid assets and no “lender of last resort facility” with the central bank. Conventional banks’ treasuries place the excess funds overnight in money markets, lend the surplus in the interbank network, or invest in government securities. IBB cannot utilise these options, and is obliged to hold relatively large amounts of non-income-generating cash (www.islamicbankingnetwork.com).

- Islamic banks’ focus of financial accounting information is on asset allocation and return from investments and trade rather than interest rate spread, provision of loan portfolios and maturities of liabilities.

- In theory, Islamic banks should guarantee neither the capital value nor the return on investments; these banks basically pool depositors’ funds to provide professional investment management. This is similar to the operations of investment companies in the West. However, for investment companies, the public are entitled to voting rights and can monitor the company’s performance. In IBB, depositors are only entitled to share the bank’s net profit (or loss) according to the profit/loss sharing ratio stipulated in their contracts, and they cannot influence IBB’s policies. However, under English law, IBB is required to provide guarantees to depositors’ capital.

- In cases of default, there is no ambiguity about control of the assets under Islamic mark-up contracts because the financial institution retains title to the asset until the agent makes all payments.

Being an Islamic bank poses internal challenges. Firstly, the bank has had to establish an Islamic Sharia Committee to assess whether its activities are in accordance with Islamic law. This is time-consuming, costly, leads to confusion about what Islamic banking really encompasses, and hinders its widespread acceptance. It also makes it difficult for Western regulators to understand the idea of Islamic banking. This lack of understanding, coupled with lack of regulation, causes tension between Islamic banks and British regulators, and affects the regulators’ willingness to support such organisations. Indeed, the collapse of BCCI in 1991, a conventional bank but with many Muslims on its Board, prompted significant tightening of banking regulations in the UK, which caused Al-Baraka International Bank, IBB’s predecessor, to close down. Today, Western regulators require Islamic banks to maintain higher liquidity requirements because their operations are riskier than those of conventional banks. Until recently, the British tax system was unfair to Islamic banks because interest is tax-deductible, whereas profit is taxed. However, IBB has recently claimed a major victory in the battle with the authorities since changes in legislation have been announced.

There are few professional courses and trainings tailored for Islamic banking and this has resulted in a lack of qualified staff for IBB and has meant resorting to recruiting staff from conventional banks. However, such staff find adjusting difficult. In addition, the lack of trained staff slows innovation in Islamic products and means unqualified management.

Against a very competitive background, and the lack of awareness of what Islamic banking is, IBB was pleasantly surprised at the launch of its Whitechapel Branch in London, when 60 accounts were opened within the first four hours. Since then the bank has grown steadily and on its 10th anniversary was acquired by Qatari bank Masraf Al Rayan and renamed Al Rayan Bank Plc. During 2015, its profits doubled and by the end of 2016 the value of its retail and commercial asset booked had passed the £1 billion mark.

Case note: The sharia-compliant products are:

Case note: The sharia-compliant products are:

- Murabahah – a contract for purchase and resale, which allows customers to make purchases without having to take out loans and pay interest. The financial institution purchases the goods for the customer, and resells them to the customer on a deferred basis, adding an agreed profit margin. The customer then pays the sale price for the goods over instalments, effectively obtaining credit without paying interest.

- Mudarabah – refers to an investment on your behalf by a more skilled person. It takes the form of a contract between two parties, one who provides the funds and the other who provides the expertise. They agree to the division of any profits made in advance. In other words, Islamic Bank of Britain would make sharia-compliant investments and share the profits with the customer, in effect charging for its time and effort. If no profit is made, the loss is borne by the customer and Islamic Bank of Britain takes no fee.

![]()

4-3 Royal Air Maroc: Red, Green … and Blue?

Compagnie Royal Air Maroc was founded in 1957. It had 443 employees, a fleet of three DC3s and was able to draw on the facilities and expertise of Air Atlas, which was developed after World War II primarily to ship freight on Junkers JU52s between Morocco, Algeria, Spain and France. Royal Air Maroc now flies over 44,000 flights per year to 60 destinations in 30 countries in Europe, Africa, North America and the Middle East. The Moroccan Government holds approximately a two-thirds stake of the company’s capital.

The company is extremely proud of its “Royal” status, not surprisingly in a country that reveres and has great respect for its royal family. The proudest moments listed in its corporate history often involve the opening of facilities, or blessings of events, by members of Morocco’s Royal family. It also takes its status as the “national flag carrier” (hence the colours of Royal Air Maroc: red and green) very seriously.

Royal Air Maroc’s strategy is thus closely tied to the Moroccan Government’s national strategy. In November 2001, Royal Air Maroc initiated a strategic vision with the objective of turning the company into a national multiple service entity and driving force tied to Morocco’s economic development. Its website (www.royalairmaroc.com) proudly states that it is “fully aware of the citizen role [we] should play, Royal Air Maroc actively contributes to the economic development of Morocco and its international image” and that Royal Air Maroc’s strategy is “intimately linked to the economic and industrial dynamism of our country”. Furthermore, Royal Air Maroc sponsors almost all of the major Moroccan cultural and artistic events, such as the Fez Sacred Music Festival, the Rabat Festival, Essaouira Festival and the International Film Festival at Marrakesh.

The Royal Air Maroc Group is organised around six “principal growth activities” that relate to its core expertise in air transport and allied activities. There are three “basic areas”, as the company describes them (Regularly Scheduled Transport, Tourist Transport and Air Cargo), and three “allied areas” (Hospitality, Industrial Activities, and Service and Innovation).

Over the past few years, Royal Air Maroc has been growing nicely, with the “basic” divisions performing especially well, despite a business environment that has been difficult for airlines. The restructuring of these divisions’ activities around Casablanca’s airport (named after King Mohammed V) toward establishing “Casa” as the international airline hub linking Europe, Asia and the Americas into Africa has been particularly successful. This development has seen a great expansion in the number of services offered in and out of Morocco, through strategic partnerships formed with airlines such as Air France, Spain’s Iberia, Delta Airlines from the USA, Saudi’s Gulf Air, Tunisair and Emirates, and through growing Royal Air Maroc’s own services (the company opened up 11 new routes in 2004 and had added a further 15 by October 2005). Africa has been the biggest growth area, and Royal Air Maroc is seeking to play a leading role in developing further growth in the region. Toward this end, it recently created Air Sénégal International, a subsidiary based at Dakar, with 51% of the stock held by Royal Air Maroc and 49% by the Government of Senegal. This growth has seen Royal Air Maroc recently top 4 million passengers per year, 7bn dirhams in turnover, and acquire four new Airbus jets toward a planned fleet of 45 aircraft by 2010.

Royal Air Maroc’s latest advertising campaign subsequently promotes a strong message of confidence in the company’s future. It claims that, “in a turbulent marketplace, Royal Air Maroc affirms its assets and consolidates its strong position: this is an airline company passionately Moroccan, eager to participate in solving the big challenges facing the Kingdom, [and] modern and effective in its goals of developing tourism and industry in Morocco.” In the words of Royal Air Maroc’s own press statements: “this is an airline company perfectly armed to battle the economic ‘war of the skies’”.

However, despite this claim to be “perfectly armed”, in 2004 Royal Air Maroc announced the creation of a new subsidiary called Atlas Blue that would compete with Royal Air Maroc in the passenger air transport arena. Royal Air Maroc management explained that “the creation of [Atlas Blue as] the low-cost air carrier of Royal Air Maroc fits into the Governmental vision of initiating in our country a strong national tool geared to the development of tourist transport. This national tool will make it possible to strengthen the competitiveness of the air transport industry in our country and to turn it into a major vector for the growth of tourism in the framework of the Vision 2010 program.”

Perhaps the African continent’s first purpose-built, low-cost airline, Atlas Blue, was established with the expressed purpose of “flying certain routes from Moroccan provinces [at present Marrakesh and Agadir are the two airports served] and to and from tourist issuing markets [initially France, Belgium, Italy, Holland, England, and Germany – with research currently being done into developing Russian services] with point-to-point service”.

Atlas Blue would draw on Royal Air Maroc knowledge, facilities, capital, maintenance and other services, as well as Royal Air Maroc’s HR training facilities. But many other aspects of Atlas Blue would be separate:

- The primary distribution channel for Atlas Blue’s reservations and sales operations would be direct selling through stand-alone websites and call centres.

- Marketing: its advertising slogan is “Atlas Blue … Morocco at unbeatable prices”. Atlas Blue’s “corporate colours” are sky blue with ochre, to represent the sea and the distinctive mountains of Morocco’s inland districts (testing had shown these to be enduring images for tourists to Morocco).

- Atlas Blue’s head office would not be in Casablanca but in Marrakesh, Morocco’s premier tourist destination.

Atlas Blue’s initial fleet comprised six B737–400s with the company planning to add two further aircraft each year. However, by 2010 Royal Air Maroc was reintegrating Atlas Blue, painting all of its planes into the red and green livery of RAM thereby increasing the size of its standard fleet and refocusing the company’s competitive advantage. The Atlas Blue brand ceased to exist.

4-4 Two Brews: AB InBev vs. Your Local Craft Brewery

When I visit Interbrew’s operation in Belgium in 2003, it’s all polished steel vats and piping. It’s very different from the small craft brewing operations I’m used to and which would go on to become increasingly trendy through to 2017 and beyond.

Interbrew produces around 10 million units of Stella Artois, Interbrew’s flagship brand, each day. There are very few people to be seen, apart from the computer operators in the control room. Across the road, the old plant is now producing smaller runs of specialist brands, like the famous abbey beer Leffe, which are now an integral part of the Interbrew “family”.

Interbrew has grown very big and very global very fast, having made 24 acquisitions in 14 countries in the 10 years to 2003. According to CEO Hugo Powell, Interbrew’s seemingly paradoxical aim was to become “the world’s local brewer. Our global approach is based on strong regional platforms and supported by our great ability to adapt to local markets and cultures.”

Ludo Degelin, director of operations and manager of international technical support, explains the approach in greater detail. He begins by reviewing some of the approaches favoured by Interbrew’s competitors. Anheuser-Busch (AB), the world’s largest brewing group, tends to buy up local production facilities (important given the high distribution costs associated with beer) that can then be converted and standardised to produce their global brand – Budweiser. “It’s a good strategy that has worked well for them, but it works because they started from such a large base and they have a huge global brand. We start from a different position and in any case I don’t think their approach suits us,” Ludo explains. Guinness attempts to match local tastes (and take advantage of different licensing laws) by varying their recipe. Hence, the Belgian Guinness is stronger than in Britain, where the excise regime is a lot stiffer, and the African brew is both stronger and sweeter than the Irish. A lot of mileage can be got out of one brand in this way. However, Ludo believes this strategy is becoming problematic as drinkers increasingly move across national boundaries and are confused by the variation in what they assume to be the same product.

Interbrew, by contrast, looks to acquire breweries with brands that have a strong local identity and are market leaders, and, unlike AB, they expect to develop these brands. “It is difficult to recreate the emotional attachment that local people already have for these beers,” claims Johan Robbrecht, who works with Ludo on aspects of packaging development, “they are deeply rooted in the community, linked to particular sports and so on.” However, Interbrew does change some things. In Ludo’s words, while they do not alter the taste of a local brew too radically, they do seek to “clean up the production, using our technical experience and expertise, and then effectively relaunch it. Once this is done we offer the local management the opportunity to brew Stella, which we are building as our global flagship brand. However, [unlike Guinness] they must be able to produce it using the Belgian recipe so that it tastes as close as possible to the Stella brewed in Leuven. And, importantly,” Ludo adds, “it must come into the local market at a premium price in keeping with a premium brand.”

Over time, Interbrew aims to operate high-volume local brands that generally tap into that area’s traditional masculine sporting culture in tandem with Stella as the premium more refined brand “over and above these”, to use Ludo’s words. In this way, Ludo believes that Interbrew avoids pitfalls such as those encountered by its competitor Heineken as it attempted to penetrate Eastern Europe. In one country in particular, its approach was to discontinue local brands and replace their production with Heineken. This caused local resentment, with Heineken seen as a foreign intruder even though local people produced the beer. Then, because of Heineken’s global branding, it had to be sold at a price that very few drinkers in the East could afford (any lower would diminish the value of the product in neighbouring countries).

Ludo sees the way that Heineken now follows the same approach to international development as Interbrew as a vindication of Interbrew’s strategy. However, he stresses that tolerance for local difference must have its limits. Just adding more and more brands to the portfolio creates logistical and organisational problems, and the cost savings that can be made by discontinuing brands that are not performing must be realised in a company of Interbrew’s size. Plus, it has to be admitted that some of the local brews are not, in Ludo’s diplomatic words, “as good as they could be”. Indeed, Corporate Marketing Director Johan Peeters points out that there are some global constants in beer. “For example, if a beer is colder people will drink more of it: physiologically this is true, and this is why Guinness is brewing colder now. And all people appreciate a beer that is more consistent and technically better brewed.” However, Ludo and Johan agree that beer is also connected to human emotions and traditions. So, if you are going to change production approaches, recipes or temperatures, it must be done gradually. That local people do not like to see their traditional tastes trashed appears to be another “global constant”.

Despite the challenges associated with its rapid internationalisation, Interbrew has little option but to grow quickly given the nature of developments in the brewing industry. Analysts predicted that three or four players will dominate the world market by 2015. Stefan Descheemaeker explained the situation with a simple diagram, with profitability on the vertical axis and size on the horizontal. Between the axes he draws a “U” shape. “In the future, only the smallest micro-breweries and the largest groups will exist. You cannot survive in the middle.”

In fact, things have moved faster than anybody predicted. Interbrew became InBev when it acquired the South American brewing group Ambev in 2004. Then InBev and Anheuser-Busch combined in 2008 to become AB InBev. In 2016 AB Inbev absorbed SAB Miller to become a dominant global brewing giant.

While it is true that there are almost no breweries in the middle of Descheemaeker’s “U”, maybe that U is on its way to becoming an “I”? How on earth can your small local craft brewery compete with the muscle and guile of a behemoth like AB InBev with its family of hundreds of local brands combined with its global buying power?

4-5 Cereal Brothers: Cereality or Seriously?

The idea, explains David Roth, co-founder of Cereality Cereal Bar and Café, “is to become the Starbucks of cereal”. Cereality simply provides bowls of common branded cereals such as Cheerios, Lucky Charms and Quaker Oats to which customers can add toppings and milk. And many business commentators and experts believed that Roth and co-founder Rick Bacher were really on to something: watch the pair discussing the company on Donny Deutsch’s The Big Idea (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hcJ7pv0YyXA).

Roth and Bacher began testing a prototype store at the end of 2003 at Arizona State University (the store took just two months to turn a profit as students flocked to it), and by the end of 2004 new outlets had been opened in Philadelphia and Chicago with 15 more stores planned to open in 2005. Thinking further ahead, Roth and Bacher were also negotiating for space at train stations, arenas, airports and hotels.

The founders claim they created Cereality “to celebrate the very personal nature of enjoying a good bowl of cereal, anywhere and at any time. It’s a life-long staple, and yet nobody had ever figured out a way to make it work in fast food.” At Cereality customers can get a 32 oz. bowl of branded cereal, or combine brands as they wish, and select from toppings like fruit, nuts and candy and different kinds of milk for about $3. Or they can choose ready-made mixes selected by Cereality staff (called “Cereologists”). Cereality also does Smoothies made with cereal (Slurrealities™); and goods baked with cereals (Cereality Bars™ and Cereality Bites™). Bacher seems to be serious when he boasts: “Cereality is so unique, it has a patent pending.”

Customers are greeted by waiting staff wearing pyjamas in surroundings that are comfortably homely. “I wanted to create a totally cool experience where all of those (cereal) rituals and habits can be celebrated out of the home,” explains Roth. In so doing, Cereality is hoping to cash in on the comfort and nostalgia that people attach to breakfast cereal. USA Today wrote that this “latest fast-food concept is so absurdly simple, self-indulgent, and reflective on one’s inner child that, well, how can it fail?”

Cereal makers, who have been trying to find an outlet for their products beyond the breakfast table for decades and have been battling the current trend toward “low-carbs” that has contributed to an 8% decline in cereal sales in the five years to 2004, have been keen to get behind Roth and Bacher’s venture. Quaker has invested an undisclosed amount in Cereality, and General Mills and Kellogg have offered business advice. In return, the big cereal companies not only get another distribution channel, but valuable information as well. Cereality kiosks gather interesting data on who’s buying what and what combinations of cereals and toppings are popular. The pilot store has already yielded some surprises, such as a strong yearning among collegians for Cinnamon Toast Crunch, and that Quaker’s old-fashioned Life brand is the number one seller.

Roth claims to have been inspired by the cereal-loving characters on the cult 1990s TV show Seinfeld, the show which boldly claimed to be “about nothing” but was greatly loved and tremendously successful. There are some that might say that serving bowls of cereal commonly available in any supermarket is similarly a “nothing” strategy. But could Cereality become as successful as its role models Starbucks and Seinfeld?

Search “Cereality” online and you will see that they couldn’t. But Cereality’s failure to fire as a global chain like Starbucks, as envisaged by Roch and Bacher, has not deterred others with similar ideas.

Figure 4.7 London’s Cereal Brothers

An article in the June 2015 issue of etihadinflight magazine focuses on a start-up by twin brothers Gary and Alan Keery called Cereal Killers. It reports that “[t]he latest food trend in London is upmarket, inventive fast food – and the newest favourite is cereal”.

The article describes people “queuing in droves” outside Cereal Killers’ Shoreditch café, with the open-all-hours cereal concept, born when the brothers were hungover, got up late and realised there was nowhere to get a bowl of cereal, going better than the Keerys’ could have ever imagined.

As Gary explains: “for anyone who thought we were mad we are certainly proving them wrong. It’s a bit more fun to think outside the box – customers aren’t just buying the dish, but a whole experience that goes with it. If you have a theme, like cereal, it’s much easier to create that sort of fun.”

This whole experience includes cereal-inspired art, dozens of popular brand cereal choices served out of the box, cereal-related merchandise like lip balm and pocket mirrors, and the brothers’ own combinations of the cereals and flavoured milks.

Cereal Killers has generated a lot of media interest too, including a heated exchange on Channel 4 news where the Keery brothers were accused on overpricing their cereal at £3.20 a bowl.

Nevertheless the etihadinflight article concludes that “[t]he cereal trend shows no sign of letting up … Not only are the Keerys opening a second cafe in Camden, North London, but two similarly minded best-friends have opened a Moo’d Cereal House in Leeds.”

Writing your own “competitive advantage” case

Writing your own “competitive advantage” case

Refer to the section “Using Strategy Pathfinder for Assessments and Exams” at the end of the book (see p. 385). Under “the Mini Case” and “the Briefing Note”, guidance is given about how you can create your own case. You may already have an interest in organisations around you that you would like to understand in more depth – and this is a good vehicle for that purpose. There are also a large number of websites that highlight interesting organisations that you might want to find out more about. For instance:

- Websites for national newspapers

- Forbes

- TechCrunch

- uk.businessinsider.com

- www.fastcompany.com

- www.huffingtonpost.com.

It is also worth noting that in the UK there is an excellent website for company information at Companies House. The address is https://beta.companieshouse.gov.uk/.

In addition, there are good free sites for financial information on companies such as

- Google Finance

- Yahoo Finance

- Various stock exchanges.

The Motley Fool website can also provide some provocative investment suggestions at www.fool.co.uk.

![]()

Notes

- 1. The debate between the impact of industry and the firm on company returns is an ongoing one. Richard Rumelt's (1991) eminently sensible suggestion is that an intermediate position between the two is the most useful, with actual balance contingent on the particular industry.

- 2. Despite what most MBA students believe, this insight pre-dates Michael Porter by some time. As far back as 1817 the economist David Ricardo pointed out that industry prices are set by the marginal (highest cost) producer and so other producers with lower costs (competitive advantage) make higher levels of profits. That is, “[t]he exchangeable value of all commodities, whether they be manufactured or the produce of mines, or the produce of the land, is always regulated, not by the less quantity of labor that will suffice for their production under circumstances very favourable but by the greater quantity of labor necessarily bestowed on their production by those who have no such facilities, by those who continue to produce under the most unfavourable circumstance.”

- 3. In his earlier version of this matrix, Porter (1980: 39) used the term “uniqueness perceived by the customer” instead of “differentiation” advantage and it may have reduced confusion if he had stuck with the idea of uniqueness as an advantage and differentiation as a strategy aimed at building that uniqueness.

- 4. Mintzberg, H. (1998) Generic strategies: Toward a comprehensive framework, in Lamb, R. B. and Shivastava, P. (eds), Advances in Strategic Management, JAI Press.

- 5. Bowman, C. and Faulkner, D. (1997) Competitive and Corporate Strategy, Irwin.

- 6. A good read on game theory and strategy is Dixit, A. K. and Nalebuff, B. J. (2008) The Art of Strategy: A Game Theorist's Guide to Success in Business and Life, John Wiley & Sons.

- 7. Kim, W. C. and Mauborgne, R. (2005) Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant, Harvard Business School Press.

- 8. Cummings, S. and Angwin, D. N. (2004) The future shape of strategy: Lemmings and chimeras, Academy of Management Executive, 18(2): 1–16.

- 9. What the case does not reveal is the extent to which Jack Cohen persevered with a no-frills philosophy throughout his tenure firstly as owner, then as chairman/CEO and finally as “honorary life president” but non chairman. He could never resist buying cheap goods or cheap, rundown premises from which to sell these cheap goods. On one occasion a consignment of tins of “Gambos” arrived that he had purchased on holiday in South America. Nobody at Tesco knew what they were but guessed from the label that they must be plums and so stocked them in the canned fruit section. They turned out to be seeded (and hot!) peppers. In 1973 Cohen often made unilateral deals. In one instance bought a set of rundown premises with stores so dilapidated that some even lacked planning permission to be in existence. Tesco's Board defied Cohen and went back to the previous owner and persuaded them to buy them back. This deal and another failed decision signalled the end of Cohen's unchallenged rule.