9

Crossing Borders

You may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one;

I hope some day you’ll join us, and the world will live as one.

John Lennon (1940–1980)

When I am at Milan, I do as they do in Milan; but when

I go to Rome, I do as Rome does.

St Augustine (354–430) Roman theologian and philosopher

James Dyson is a British inventor famous for creating a revolutionary new vacuum cleaner that didn’t use a dust bag and was significantly more efficient than competitor products. This product innovation that turned a “boring” domestic machine into a high-performance object of desire was an immediate hit in the UK market and soon Dyson was selling his product to overseas markets as well as at home. Dyson followed this triumph by inventing a revolutionary washing machine containing two contra-rotating drums to give greater performance than other models, hand dryers, air conditioners and supersonic hair dryers. Such successful entrepreneurialism earned Dyson national recognition and his company “cult hero” status in Britain. So, imagine the shock when he announced that his factory in Malmesbury, England, was to close and all manufacturing moved to Malaysia. There was widespread outcry in the UK press and from the trade unions. “This latest export of jobs by Dyson is confirmation that his motive is making even greater profit at the expense of UK manufacturing and his loyal workforce. Dyson is no longer a British product.”1 Not only would 865 jobs be lost, but this also seemed to symbolise so much of British industrial history: the loss of yet another world-beating product overseas. Why would Dyson, a hero of British entrepreneurialism, risk the wrath of his countrymen for the sake of profit?

Dyson is just one example of an organisation that rapidly succeeds in its home market, quickly begins to export its products and then moves production overseas to reduce costs and/or to be closer to other markets. This raises a number of questions central to international business strategies. Why do countries specialise and organisations trade across national boundaries, and how recent is this phenomenon? Why do some organisations leave their home country for another? What are the obstacles to crossing borders? What strategies are used for competing internationally? Which borders should be crossed? What methods can be used to enter different countries? How might an organisation make a strategic retreat? And how can firms structure themselves for competing across borders?

Why Do Countries Specialise and Organisations Trade Across National Boundaries?

Although a relatively new academic subject, international business itself is not new. Evidence survives of the Phoenicians mining for tin in Cornwall, England, in 500 BC. The Cistercian monks engaged in pan-European wool trading in the 13th century. In the 15th century, the rise of the city republics, such as Venice, saw substantial integration into international trade. Soon afterwards, in the Age of Empires, the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, French and British controlled and traded with many far-flung countries. The political power of these countries rested upon the economic power of trade, which came to be dominated by trading companies such as the East India Company (India), Hudson Bay Company (North America) and Inchcape (Asia).

In essence, trade results in a higher level of economic well-being for its participants. This logic, at the level of the parent nation, was articulated famously in Adam Smith’s theory of absolute advantage: “If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it off them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage.”2 Each nation, then, should specialise in producing goods in which it has a natural or acquired advantage. For example, Scotland has an absolute cost advantage over Spain in producing whisky. Nike, for instance, has benefited from the absolute advantages of different countries as it is carrying out R&D in the US; fabric, rubber and plastic shoe component production in Korea, Taiwan and China; and assembly in India, China, the Philippines, Thailand and other low-wage locations.

What if a country has no natural advantages? To address this question, in 1817, David Ricardo developed a theory of comparative advantage, which examined the relative costs of production between goods in each country.3 On this basis, countries should produce and trade in goods that they are best equipped to produce, even though their cost of producing other goods may still be lower than the countries with which they are trading. Traditionally, these theories focused on natural resource endowments, population and capital, but critical roles are now recognised for social and cultural factors such as human capital and management capabilities.

To improve on the rather static nature of the early theories, a more dynamic model was proposed by Hecksher (1919) and Ohlin (1933). Their HOS model of factor endowments argues that as a country specialises in a particular product, the main factor of production, such as land, labour or capital, becomes increasingly scarce and expensive. As a consequence, countries that may have a large labour force, encouraging labour-intensive production, are likely to experience rising wages. To compensate for such pressures, countries need to develop other advantages. In order to explain the development of Japan and the catching-up process of industrialisation, Kaname Akamatsu coined the term “The flying geese pattern of development”. This model was presented to the world’s academic audiences in 1961. It explains Japan’s post-war transition away from cheap labour, through acquiring technology and developing capabilities, as reflected in changing industry emphases on textiles, chemicals, shipbuilding, cars and electronics. It also explains the rapid rise of NICs (newly industrialised countries) by recognising that comparative advantage shifts across countries over time. Such Tiger economies, including Singapore, Taiwan, Malaysia and Korea, have grown organisations that are beating Japanese industry in many areas and some, such as Samsung, can now claim to be world leaders at the forefront in several product areas.

Why Do Organisations Leave Their Home Countries?

Within these broad national trends, organisations attempt to adjust to changing contexts such as those identified by ESTEMPLE (see Chapter 2). For organisations such as Samsung, with growing demand for its products in overseas markets, direct investment in production capacity abroad becomes increasingly attractive to reduce logistics costs. As the product becomes standardised, production may be moved to areas where manufacturing costs are low. This dynamic is captured in Raymond Vernon’s article “International Investment and International Trade in the Product Life Cycle”. Vernon suggests an international product life cycle4 theory to explain why the location of industries changes. “As production and consumption increase, production costs decline and markets expand, so exports increase. With increasing competition, price cutting forces production to shift to cheaper countries.” On this basis, we have an explanation for the transfer of Dyson’s manufacturing as well as the cataclysmic decline in traditional British industries such as mining, shipbuilding and textiles.

Some organisations may be more likely than others to internationalise. Organisations that own hard-to-replicate proprietary advantage, such as technology, brand name or distribution, may come to dominate the home market and later overseas markets.5 This does not fully explain all differences between organisations and industries. For instance, Tesco, which has been the undisputed leader in the UK supermarket industry for many years, is still primarily a domestic operation. This oligopolistic theory was refined in John Dunning’s eclectic theory, which centred on ownership, location and internalisation (OLI). The organisation has to: have some ownership of specific unique assets that can be transferred (O) and which will offset the additional costs of competing overseas; locate where cheap capital, labour and other resources can be obtained and where logistics costs can be minimised in terms of transportation and tariffs (L); be able to make transfers internally to retain control of revenue generation (I). Those organisations that derive most from internalising activities will be the most competitive in foreign markets. The eclectic theory suggests that where an organisation’s OLI advantages are high, organisations are more likely to prefer an integrated mode of entry across borders.6

Organisations, then, are motivated to cross borders to exploit new market opportunities and to reduce labour costs. They may also be motivated by needing lower cost supplies and/or securing procurement such as key raw materials. The rising costs of R&D and technology may need investment greater than can be sustained in the domestic market. Having operations in overseas countries may reduce the risk of fluctuating exchange rates and also allow arbitrage benefits by using resources in one country to benefit another. The “Californianisation of society”, or globalisation of tastes, increases pressure for universal brands and products. This can be as much at the personal level, with products such as smartphones and iPads, as with business consumers wanting similar service and products around the world for all their subsidiaries. Such standardisation suits high-tech products with low cultural content, and encourages economies of scale and scope in producers. Other pressures encourage the integration and coordination of operations in different countries. When the blockbusting film The Matrix was launched, it had the distinction of being the first film to open simultaneously around the world. Where there are short product life cycles, such as with movies and computer software, it is now essential to have coordinated global product launches to reduce the time for competitive response and illegal copying. Microsoft’s Windows, for instance, launches simultaneously worldwide. Coordination also allows learning through the transfer of best practice, people and information. These advantages of gaining new markets, reducing costs, timing benefits, learning and arbitrage opportunities are real but have to generate a competitive advantage for the organisation. Specifically, crossing borders must offer value propositions more attractive than those available at home. Even if opportunities seem to satisfy this criterion, numerous obstacles exist which may impair their realisation.

What Are the Obstacles to Crossing Borders?

Obstacles can be classified into four types: (1) political and legal barriers, (2) commercial factors, (3) technical issues and (4) cultural factors.

Political and legal barriers occur through the use of regulation, duties and quotas that can limit free flow of people, cash and products. For instance, to impede the importation of Japanese electronics, the French required all imported goods of this type to go through a single customs point, located in the mountains. Ownership policies, such as refusing total ownership (particularly if the industry is perceived as strategic) and only allowing joint ventures, for instance, may disrupt attempts to improve international coordination of business. This was the case for foreign companies trying to enter the Chinese market during the 1990s, when only joint ventures were allowed.

Commercial factors may include limited access to distribution networks (as these may be tied up already by incumbent competitors), the need for customisation, and differentiated approaches to sales and marketing.

Differences in technical standards can increase costs, and transportation difficulties can reduce the benefits of economies of scale and standardisation. There may also be a spatial need to be present locally, for instance in the provision of health care.

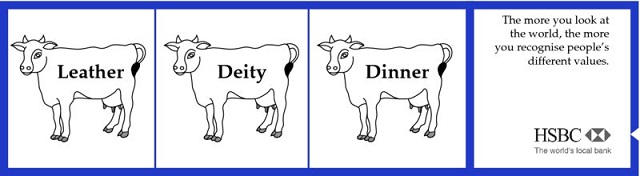

Cultural barriers may exist as differences in social attitudes, beliefs and norms, and in terms of language, etiquette and way of interacting. These may hamper interactive communication and reduce the benefits of standardisation. For instance, the British are notorious for using language in an opaque way. Where the British say: “I hear what you say”, foreigners will understand this to mean “He accepts my point of view”. In actual fact, what is meant is “I disagree”. When the British say: “That’s an original point of view”, foreigners will tend to think that their ideas are interesting and liked, whereas what is meant is “You are crazy, or very silly”. In some countries, great emphasis is placed on getting to know the people one is negotiating with, whereas other countries focus more on the transaction itself. For one large UK company that recently acquired a firm in Spain, the UK Director decided to visit the Spanish MD for a discussion about strategy. As time was tight, and in order to be efficient, the UK Director requested a working lunch over sandwiches. The Spanish MD regarded this as a personal slight as removing lunchtime also removed the time, necessary in his eyes, for the building of relationships – critical for doing business in Spain. Furthermore, where was the Spanish firm to get sandwiches from?

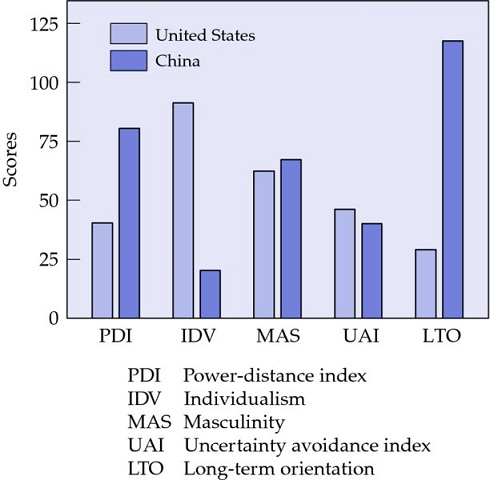

From our examples, one can perceive many different aspects of national culture. Studies aimed at crystallising such differences have concentrated on: (1) ethological perspectives, such as Hall’s study7 on silent differences like the importance of time, social and physical space, material goods, friendship, types of agreement and the relative importance of context versus content; (2) country cultures, such as Huntingdon’s work8 identifying civilisation clusters by language, religion, beliefs and institutional and social structures; (3) economic cultural differences, such as Whiteley’s work,9 which examines business systems and forms of capitalism; and (4) country cultures based on managerial values. Probably the most famous, and certainly the largest survey into managerial values, is by Dutch academic Geert Hofstede, who surveyed 116,000 IBM employees across 53 different nations to assess national cultures based on work-related values.10 With subsequent refinements, Hofstede categorised them according to five dimensions:

-

Power-distance, or the degree of inequity among people that a country’s population sees as normal.

Countries such as the USA, Germany and the Netherlands scored low on power-distance, while Russia and China scored high.

-

Individualism vs. collectivism, or the degree to which people prefer to act as individuals rather than as members of groups.

Countries or regions such as Hong Kong, Indonesia and West Africa scored low on individualism; while the USA and the Netherlands scored high.

-

Masculinity vs. femininity, or the degree to which values often labelled masculine (e.g. assertiveness, competitiveness, performance orientation) prevail over those often labelled feminine (e.g. relationships, solidarity, service).

Scandinavian countries, the Netherlands and Russia scored low on masculinity; Japan and Germany scored high.

-

Uncertainty avoidance, or the degree to which people preferred structured rather than unstructured situations.

Countries such as Hong Kong, Indonesia and the USA scored low, while Japan, Russia and France scored high.

-

Long-term vs. short-term orientation.

Countries such as Japan and China scored high on long-term orientation, whereas the USA and Britain scored low.

These different orientations can affect many things that relate to strategy, from the type of management theories that one nation develops or favours, to a nation’s preference for certain types of action over others, to the way staff behave, develop and implement strategy.

While Hofstede’s work has been criticised for focusing on a single organisation, other researchers, such as Laurent,11 have sampled more broadly and still identified systematic patterns of national differences among managers in their assumptions concerning power, structure, roles and hierarchy. Later research by Fons Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner, following in Hofstede’s footsteps, has identified cultural discriminators12 by examining value-oriented differences.

Dimensions such as those identified by Hofstede have been used extensively by international business researchers to understand variations in implementing strategies in different national contexts.13

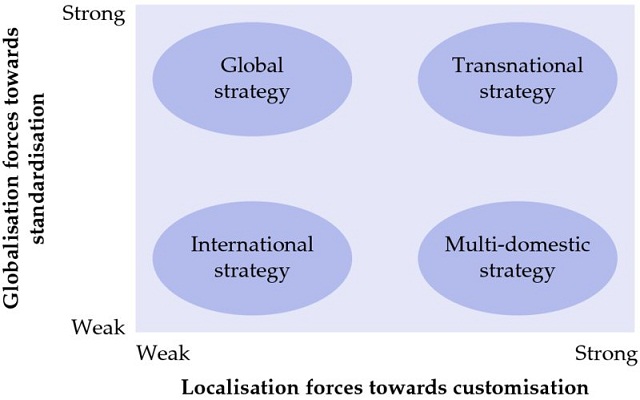

The four categories of obstacles to global integration identified above push organisations away from standardisation towards local customisation. While this means that scale advantages are harder to achieve, there are benefits of being focused more locally. These include being more responsive to customers, enabling a better understanding of their needs and being able to adapt more quickly to their demands. A useful framework for capturing this tension between the attractions of globalisation and localisation is captured in Prahalad and Doz’s global integration/local responsiveness grid (see Figure 9.1).14

Figure 9.1 Global integration/local responsiveness grid

(Source: adapted from Prahalad and Doz, 1987)

What Strategies Can Be Used for Competing Internationally?

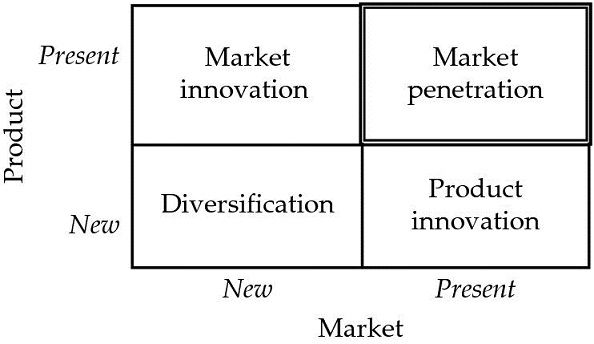

First outlined in 1965, Igor Ansoff’s Growth Vector Components Matrix is perhaps the first, and still one of the most useful, frameworks for thinking about development options in strategic management. Figure 9.2 shows an adapted version of the matrix with its four generic growth choices: diversification, product innovation, market innovation and market penetration. There is a suggestion that for risk-averse companies the best pathway to adopt is to expand through market penetration as the organisation is well versed in the dynamics of competition in its own sector. It is only when this route for growth becomes limited, perhaps due to regulators trying to reduce the potential for monopoly power, that alternative directions should be pursued, and for risk-averse companies this often means market innovation – expanding into new markets, perhaps in overseas territories but selling current products. This is relatively low risk although it can still go wrong – see Tesco’s problems in trying to break into the Californian and Chinese markets, or Walmart trying to enter Germany. Organisations may then wish to begin product innovations, although these can be riskier, more expensive and longer-term propositions than overseas expansion. When, finally, these avenues are becoming exhausted, organisations may engage in diversification (sometimes called conglomerate diversification) – entry into new markets with new products. This is widely perceived as the riskiest growth pathway (see Chapter 7’s discussion on diversification). More recent versions of the policy matrix tend to focus more upon the deployment of current capabilities and competencies, but the fundamental idea of staying with what you know before expanding into the unknown remains true. From this one can gather that overseas expansion potentially offers a riskier route to growth than just growing in domestic markets, although the opportunities may be substantially greater than in the home market. If growth objectives cannot be met at home then overseas expansion is likely.

Figure 9.2 Strategic development options matrix

(Source: adapted from Ansoff, 1965)

Another way of thinking about strategic options for acquisition is to consider Figure 9.3, an adapted version of the Five Forces of Industry (first outlined in Chapter 3). This shows how an acquisition can help an organisation bridge borders between itself and potential competitors, customers, suppliers, substitutes or new unrelated opportunities.

Figure 9.3 Cross border types of M&A

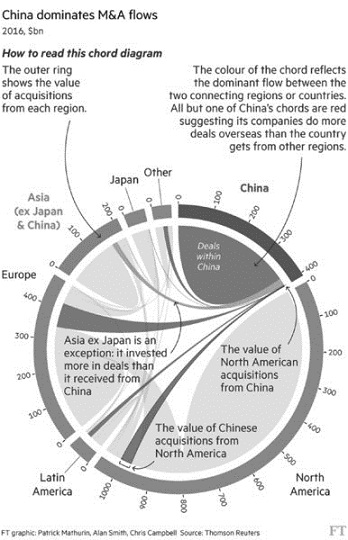

Each of these different types of acquisition may be in the same geographic area as the acquirer such as Tesco/Booker, but also might be in a different territory such as Teva Pharmaceutical’s acquisitions of biotech companies around the world. In 2016, $173bn of cross-border M&A were transacted (37% of all M&A by value and 21% by numbers of deals). At the time of writing, China dominates the outward flows of M&A and 2016 saw its biggest bid ever by ChemChem buying Swiss agribusiness Syngenta for $44bn (see Figure 9.4). At the moment, China’s outbound M&A focuses most on the EMEA region but also carries out a lot of deals in the US. However, there appear to be concerns in China that this pattern of activity is not as desirable as it once was.

Figure 9.4 China dominates outward flows of M&A

(Source: Financial Times, 29 September 2016; article by Arash Massoudi in London, Don Weinland in Hong Kong, and James Fontanella-Khan in New York)

The degree of pressure from globalisation forces requiring standardisation and localisation forces requiring local cultural richness will determine the strategies that organisations will adopt. Figure 9.1 identifies the following four dominant styles. International strategy, where organisations have (a) just begun to expand overseas but do not perceive a dominance of either dimension and (b) no need to customise a product, and its high and distinctive value gives few incentives to invest in scale economies. This may be a pre-competitive state, so new competitors may force choices. Global strategy, which emphasises economies of scale through the standardisation of products and services. This strategy lends itself towards high-volume production and very efficient logistics and distribution systems. A weakness is geographic concentration of such activity and isolation from target markets. Multi-domestic strategy, which emphasises differentiating products and services through adapting to local market needs. Customisation, through tailoring packaging and service at the point of sale, incurs greater costs but there are advantages in greater flexibility and responsiveness to local demands, as well as allowing differential pricing across different markets. Transnational strategy, seeks to optimise the trade-offs between global and multi-domestic strategies by dispersing the organisation’s resources according to their most beneficial location. Typically, activities close to the customer are more decentralised and those further away are more centralised as less adaptation is required. The potential risk is whether the value of local adjustment is really realised as the successful melding together of two organisations’ resources, processes and structures is needed. This requires a “recombination” capability which is vital for creating and capturing value. Successfully managing this capability is the highest-order competitive advantage of the MNE and yet is very difficult to achieve as it presents a paradox – strong organisational routines are key for efficient organisational processes and yet their rigidity can also be detrimental to agile recombination. These internal tensions and their criticality are highlighted by Cummings and Angwin’s (2004) value chimera (discussed in Chapter 4), where different organisational approaches to the paradox are illustrated.

Which Borders Should Be Crossed?

With forces pushing organisations to expand overseas as well as opportunities attracting them to other countries, organisations need to decide on where to expand or move to, and what method(s) to use. Through entering another country, organisations ought to earn a return higher than the risk-adjusted weighted average cost of capital (WACC). This focuses attention on both the opportunities, in terms of market prospects and competitive conditions, as well as the risks of operating in that territory.

Analytical techniques outlined in Chapter 2 can be used to assess the dynamics of the macro-environment of a new country. There exists considerable macro data on economic variables (e.g. GDP per capita, disposable income, investment rates), social data (e.g. urbanisation levels, socio-economic distribution), demographic factors (e.g. population profile) and institutional variables (e.g. government spending, quality of infrastructure) on websites of the Economist Intelligence Unit (www.eiu.com), the World Bank (www.worldbank.org) and Business Environment Risk Intelligence (www.beri.com). These data allow regression analyses to identify drivers of spending/potential spending patterns. For instance, one important relationship recognised through this approach is the middle-class effect, which shows that an increase in GDP per capita can have a disproportionately larger positive effect on middle-class disposable income. A small increase in GDP, therefore, can result in great increases in spending on aspirational goods, such as smartphones and 3D TVs, by the middle classes.

Further insight into a country’s competitive advantage can be gained through the application of Michael Porter’s country Diamond.15 The framework (introduced in Chapter 5) is based on the principle that the national environment exerts a powerful dynamic influence on the performance of the organisation. The level of domestic rivalry in particular is critical for promoting improvements in other local factors – such as skilled labour, R&D capability and infrastructure – and geographical concentration magnifies the interaction between these factors. The framework, while useful, has received criticism for being based on data for 10 countries with greater economic strength/affluence than most countries in the world. The roles of chance and government seem to be presented in a positive way, but chance is unpredictable and both can act against the interests of business. While the Diamond is presented as a technique for national analysis, it must be applied in company-specific terms because “firms, not nations, compete in international markets”.16 Porter contends that only outward foreign direct investment (FDI) is valuable in creating competitive advantage and that inbound investment or foreign subsidiaries are never a solution to a nation’s problems. This conclusion has been challenged empirically.17 The model also does not adequately address the role of the multinational enterprise (MNE) and perhaps this ought to be listed as the third outside variable. For MNEs, their competitiveness is more influenced by the configuration of Diamonds outside of their home countries and this may impinge on the competitiveness of home countries.18 For different countries, then, different Diamonds need to be constructed and analysed.

For smaller countries, such as Canada, Finland and Norway, there could also be a case for using a “double Diamond”.19 Canadian organisations, for instance, needed greater economies of scale than could be obtained entirely within the domestic market. They now produce for the North American market as a whole and so are in direct competition with organisations operating in a Diamond of their own in the US. They can no longer rely entirely upon their home country’s Diamond and natural resource base. For corporate strategy, this means that the two countries of Canada and USA are integrated into a single market and for this reason a Canadian/US double Diamond is appropriate.

Porter suggests that countries, and regions within countries, can form regional clusters that are attractive for business development. Examples of such clusters might be Silicon Valley in the US, Sassuolo near Bologna in Northern Italy for ceramic tiles, and around Banbury, Oxfordshire, England for Formula 1 racing cars. Clusters promote competition, concentration and reinforcement. Networks of businesses and supporting activities in a specific region, where flagship organisations compete globally, may include private and public sector organisations, think tanks, support groups and educational institutions. It is no surprise that high-tech clusters have formed successfully around universities in the UK such as Cambridge, Oxford and Warwick, and in developing countries there are many initiatives to form clusters in order to help local businesses export their products.

What Methods Can Be Used for Crossing Borders?

Having decided on which country to enter, the organisation has to decide on an entry strategy and its timing. The entry strategy will be determined by, among other things, the organisation’s resources and capabilities for establishing an overseas presence and the transaction costs of negotiating, monitoring and enforcing agreements; the costs of transportation; and information costs.20 The least exposure or involvement in the overseas country would involve licensing; a contractual arrangement whereby products/process technology are transferred to a licensee for commercial exploitation for royalties. Other methods used where direct investment is not justified include franchising and the use of agents and distributors. The latter two are frequently used by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), the former for the logistics of stocking, transporting and billing, the latter more for taking orders and as a salesperson. Where low intensity of investment remains but greater ownership is required, a representative office is used. This is also a popular method, being perceived as a stepping stone for future and greater engagement. Where greater commitment is intended, although ownership is limited, then the organisation may engage in a strategic alliance, which can include a joint venture or being part of a consortium. Joint ventures are the main form of foreign direct investment in emerging markets and are often encouraged by the governments of the overseas country so their citizens can engage in industrial development without loss of control. For the entering organisations, they gain local market knowledge and contacts with decision-makers. Often joint ventures have a limited life-expectancy and can end up being wholly owned by one of the founding companies. A useful typology of joint ventures can be found in the book by Dussauge and Garrette21 and suggestions for effective management in Hamel, Doz and Prahalad’s paper “Collaborate with your competitors – and win”.22

If organisations entering a country are prepared to make a substantial investment in order to gain greater control of a cross-border development, then they may either opt for a wholly owned subsidiary or an acquisition. Setting up a wholly owned manufacturing facility, sometimes called a greenfield site, is the way that Dyson, our opening example, has gone. While this is expensive and can take time, through complete ownership, the quality of production can be controlled and the Dyson vacuum cleaner can benefit from the lower-cost labour force – provided local obstacles are navigated. A more popular approach, primarily because of its speed advantages, is to acquire a pre-existing local operation.

While it is easy to see how a cross-border acquisition can potentially add value, it is always important to be aware of the common pitfalls that lead to such values being over-estimated and under-achieving. Apart from the generic reasons why acquisitions may underperform, such as inadequate due diligence (the pre-acquisition investigation of the target company), lack of integration planning, over-payment or hubris, cross-border acquisitions can present additional difficulties related to the acquired organisation operating in very different political, social/cultural and economic environments. Physical distance may present coordination difficulties and finding ways in which the new organisation can operate in a synchronous way across very different social/cultural landscapes can be a massive challenge. Even the most apparently trivial issues can be symptomatic of deep differences between organisations and can cause untold trouble. For instance, when setting a time for a meeting, in some cultures executives will arrive well before hand in order not to miss out whereas in other cultures it would be remarkable if they managed to arrive within an hour of the prescribed time – indeed in some extreme cases, they may not even believe they need to arrive on the same day! The implications are that in order to manage cross-border acquisitions, acquirers must take into consideration an additional layer of fundamental issues in order to hope for success. For a more detailed discussion of cross-border pitfalls in post-acquisition integration, see Angwin’s book Implementing Successful Post-Acquisition Management.23

The timing of border crossing is especially important because organisations can either aim to gain first-mover advantages or wait and become fast followers. The problems with first movers are significant investment and having to handle all the uncertainties without guarantees of sufficient return. However, first movers can pre-empt resources, establish their presence in terms of brands and standards, and have a head start in understanding local needs. Fast followers often need substantial resources and different strategies from first movers. They are unlikely to be the only entrants, so competition is greater. However, they are in a position to learn from the experiences of the first mover and so reduce their risks.

How Can Organisations Retreat and Retrench Back from New Markets?

In recent times, events in the Middle East have caused military, political and even business commentators to stress the importance of having a good exit strategy. As a senior CNN correspondent summed up the military lessons learnt from Iraq in the programme Crosstalk in December 2009: “Always have a clear goal, always go in with as much force as you possibly can have [and] always have an exit strategy. Or as somebody else once said: “You got to know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em, know when to walk away and know when to run.” And since the Global Financial Crisis of 2009, this has been especially true in business strategy where the skilful management of retrenchment and divestment have become increasingly important strings to the effective strategist’s bow. Indeed, for certain types of transaction, such as joint ventures, one of the most important things to establish in the initial negotiations is how each party might be able to walk away if things don’t work out – a pity perhaps that this lesson was not learned when the UK voted to leave the European Union (discussed in Chapter 2).

- Sell-offs and disposals have always been part of the MNE’s strategic arsenal as it competes in a game of global chess, adjusting its portfolio of commitments to reflect changing macro conditions and the actions of competitors. For larger organisational restructuring, there may be de-merger where the organisation breaks itself into two companies. An example is the creation of Astra and Zeneca from the company Unilever when it became apparent that separating the parent into two businesses would result in greater value than these businesses combined. And now one might argue this could be the thinking behind Unilever packaging up its spreads businesses for disposal following the failed hostile takeover by Kraft Heinz. More frequently, large businesses see that their operations in one geographic area are beginning to underperform relative to other parts of the group, or that the operations no longer fit with the group’s strategy and the decision is made to divest. This might be thought of as a proactive strategy of continuously renewing the group. It can also be that the parent is suffering from financial distress, as some large companies undoubtedly did during the recession, and may divest in order to prevent itself from going into liquidation. In the case of Shell, its vast acquisition of BG for $54bn has given it a mountain of debt to deal with. Its response has been widespread divestments on the African continent.

- While the advantages of disposal are clear for the parent company, the effect upon the disposed-of organisation may be less certain as it may have become very dependent upon resources from the parent group. There may also be significant effects upon the local overseas economy, with loss of jobs, investment, technology and economic contribution. For instance, for one automotive component supplier based in Tunisia, the exit of the German owner, who was also a major customer of the business, left the local Managing Director with a major problem of finding new customers and paying specialised employees who could not find similar work locally. With no welfare state to support the unemployed, he felt a strong personal obligation to try to keep his workforce in employment. For large divestments, local effects on employment may be severe if there was substantial population migration to this organisation in the first place, as these workers may not be able to migrate back to their place of origin and re-engage with earlier activities. In many cases, however, large companies do not aim to sever links brutally with former subsidiaries and often take significant care over trying to ensure that they can remain as viable businesses for the foreseeable future. They also have a vested interest in keeping local governments content as they may wish to engage with the country again in the future.

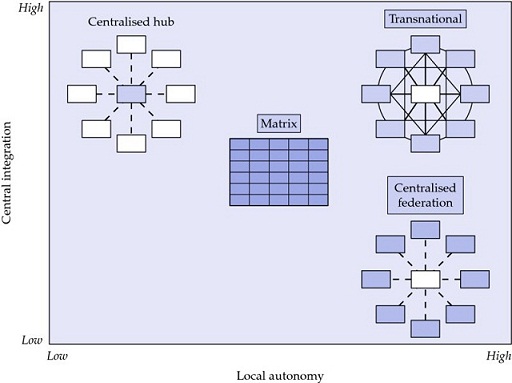

How Can Organisations Structure Themselves for Competing Across Borders?

As companies spread around the world, new organisational challenges arise. The need for coordinating and controlling, as well as adapting to local demands, places organisations under tension. The relative importance of each will vary depending on the nature of the industry. Where the need for global standardisation (and so, centralised control) is dominant, a centralised hub form is an ideal structure. Where local responsiveness is more important than global standardisation, a decentralised federation is likely. To reflect an equal emphasis on being global and local, a hybrid form was developed by ABB. The “matrix” structure was very popular at the end of the 1990s, with its dual command structure, in its simplest form, allowing employees to respond to both regional and product managers. However, its complexity led to internal confusion over responsibilities and absorbed a great deal of time in meetings and discussions necessary for coordination. Organisations have begun to move away from the matrix form and even ABB has now abandoned this structure. Bartlett and Ghoshal suggested an alternative for the global/local dilemma.24 They proposed a “transnational” design, which combines functional, product and geographic designs into networks of linked subsidiaries (see Figure 9.5). Within the network are nodes for coordination. The important feature of the transnational design is that it doesn’t focus on structure but on management processes and culture. Managerial behaviour is more important to them than structure and so a particular form is not prescribed.

Figure 9.5 Border crossing designs

(Source: adapted from Bartlett and Ghoshal, 1989)

At the heart of crossing borders, a paradox remains for managers: whether the international context is moving towards conformity as proposed by Levitt or whether this is something of a myth, as argued by Douglas and Wind,25 and it will remain fragmented. Should businesses anticipate and encourage convergence and aim to realise global synergies, accepting some local value destruction, or exploit local diversity at the expense of global efficiencies? To some extent the answer to this question lies in the cultural content or richness of products and services. For instance, food as a product is invested with a great deal of social and cultural values so that some foodstuffs cannot be sold in different parts of the world, such as Malaysian clove-based Kretek cigarettes, whereas products such as smartphones are much less culture-specific and can be sold with minimal alteration around the world. Therefore, in further understanding Dyson’s decision, discussed at the beginning of the chapter, to transfer manufacturing overseas and sell globally, we should take into account that his products have little cultural richness. The opportunities to reduce costs for Dyson outweighed the value of localisation. Dyson also recognised that global business is dynamic and that all organisations have to continue to fight to preserve, re-animate and grow their strategic advantages, not just in pastures old, but also in pastures new.

Crossing Borders Key Learnings Mind-Map

Having read and reviewed this chapter, outline what you believe to be the key learnings from the chapter and the relationships between these on the note pages below.

9-1 Kodak: Do You Feel Lucky?

When the tiger comes down from the mountain to the plains, it is bullied by the dogs.

Chinese proverb

When you are out of your element, your power/influence is greatly diminished, and yet crossing borders is about taking strategic risks. Although today Kodak is a struggling organisation, having been put into bankruptcy in 2012, for much of the previous century it dominated the world for photo film. During the high point of its success Kodak began to experience slow growth in its home markets and suffer from incursions of a major Japanese competitor, Fuji. The strong dollar helped Fuji adopt a policy of aggressive price reductions and also had the effect of making Kodak’s products more expensive abroad. For the fiscal year 1997, Kodak’s full-year earnings were down 24% and it was estimated that they had lost 3% of the consumer photo-film market.

At the same time China’s photo-film market was perceived to present a huge opportunity: China had a population of 1.2 billion, a GDP per head which had increased by 36% between 1990 and 1995, and increasing disposable income (as the Chinese Government covered major costs such as health and housing). Fewer than one in 10 households owned a camera, and the average purchase of films was only 0.1 rolls per head, compared with six in the USA. The Chinese were also very brand conscious and perceived foreign goods as being of superior quality.

Kodak seemed well placed to take advantage of this demand. It had experience of conducting business in China since the 1920s and had been awarded a specific technology transfer project in Xiamen in 1984. However, Kodak was suffering in the market as it had to rely on a Hong Kong regional shipping company to ship products to Chinese distributors, which meant a loss of control over product quality. The excessive transit differences also increased the rate of spoilage and rendered less certain the delivery and availability of products. Such practical obstacles threatened to damage Kodak’s reputation.

Kodak was also not alone in the market. Lucky Film Corporation, China’s largest and most profitable state-owned enterprise (SOE), controlled 25% of the Chinese market and benefited from Government support. The Ministry for Internal Trade helped Lucky set up a national sales network to market its products and also approved substantial loans and grants.

Kodak approached Lucky by proposing large investments and taking a large share in the firm. However, the Chinese refused to permit foreign majority ownership and the removal of the Lucky brand name. Lucky was also a supplier to the Chinese military and this strategic importance meant a foreign owner was unlikely.

The other main competitor at the time was Fuji, which had adopted an aggressive market penetration and investment strategy. Fuji had a solid distribution channel through China-Hong Kong Photo Products Holdings Ltd and had made significant investments in manufacturing with the explicit intention of shifting all compact camera production to China and Indonesia to decrease the costs of manufacture. However, it was also well known that the long tumultuous history between China and Japan meant that the Chinese community (investors, consumers, Government officials) would rather trust Meiguo (America/beautiful) than Riben Guizi (Japanese devils).

Kodak CEO, George Fisher, an executive passionate about China and with direct experience of FDI projects in his former role at Motorola, knew that Kodak had advantages over Fuji and had to expand into China, but what were the risks? Would they be lucky?

Some suggestions

Some suggestions

-

Why is Kodak considering expanding into China?

There is a mixture of push and pull factors acting on the firm. Contextual factors, such as the strengthening dollar, were favouring Kodak’s competitors’ aggressive pricing strategies. The overall industry was also stagnating. The evidence of the pressure was Kodak’s decline in profits. In contrast, China offered a vast, largely untapped market with strong consumer demand for foreign products. The recent strong growth in GDP per capita can be assumed to have greatly increased middle-class incomes and their aspirations for Western goods meant that the sale of cameras would be likely to increase substantially.

-

In what ways might Kodak be a tiger in relation to local Chinese competition and why might it be that, as the Chinese proverb suggests, “although you may be a superior force, in unfamiliar territory you may be weaker than local forces”?

Kodak has considerable strengths as a company with international operations. Its state-of-the-art technology was superior to anything owned by the Chinese, and the firm was well resourced financially. However, operating in the Chinese market was causing Kodak’s capabilities to be undermined. The practical difficulties of getting its products to the consumer in a fit state were damaging its reputation. Even though Lucky, the main player in the Chinese market, was inferior to Kodak, it had close and preferential links with the authorities, which allowed it to be subsidised and sponsored. The fact that the Chinese also did not permit foreign ownership also removed Kodak’s strength as a well-resourced company to influence the situation. Perhaps in attempting to purchase a substantial share of Lucky, Kodak had been acting as a tiger?

It is worth noting that, for China, having Kodak and Fuji as two tigers was beneficial: as they fend off one another to claim the coveted venison, the Chinese deer slowly transforms into a dragon, which neither of the two can defeat – the Chinese would continue to support Lucky.

Kodak clearly began to make much more progress when they approached the Chinese situation in a culturally more sensitive way. This approach was undoubtedly helped by having a CEO who had prior experience of FDI projects in China and who was passionate about the country.

-

What strategy should Kodak pursue?

Given that Kodak should expand into China, there are a number of options that might be pursued. Kodak can continue to attempt to link strongly with Lucky either as a major investment partner or through some form of alliance, or indeed continue to try to persuade the Chinese authorities that some sort of merger might be in Lucky’s and China’s best interests. If a major commitment could be put in place, this might give Kodak a major advantage over Fuji in terms of market share as well as close links with Chinese authorities. However, there is also the risk that a major tie up may cause Kodak to be severely hampered in how its Chinese operations would actually function, and once such a large commitment was made, it might be difficult to reverse.

Kodak might decide to try to do something different and arrange joint ventures or other types of alliance with other Chinese partners. As these firms were small in size, many such alliances might be necessary to gain scale and this could take a lot of time to put in place and take considerable efforts to manage/coordinate effectively. It is unlikely that this approach would really provide robust competition for Fuji, although the size of the Chinese market and its growth rate mean that there is considerable scope for competitors at this time.

Ideally Kodak needed a step change in the size of its Chinese operations and needed to control every aspect of product quality and distribution process. While a greenfield site was not politically acceptable, negotiations with the Chinese authorities might allow a compromise that would offer better options to the ones considered above. In terms of an optimal strategy, if something along these lines could be worked towards, Kodak should also be continuing talks with Lucky to prevent the chance that Fuji might take this opportunity and completely dominate the market.

Hofstede’s dimensions suggest major differences between American and Chinese cultures (see Figure 9.6).

Figure 9.6 Geert Hofstede’s 5D model comparing China and the USA

Substantial differences are clear for power-distance, individualism and long-term orientation. These differences should be taken into account by the Americans (on the basis that this deal is in a Chinese context). Kodak will need to adapt its negotiation style to recognise that, for the Chinese, building trust and aiming for long-term relationships are important, underlining the key issue of long-termism. For the Americans, where there is greater emphasis on rapidity and a focus on getting a contract signed, learning to be patient is important. They must recognise that for the Chinese this is more about building a long-term relationship. The American top-down decision style and use of only a few specialists in a negotiation team will be faced, provided that the negotiation is important, with a large Chinese delegation among whom decision-making is consensual. To Westerners, the opaqueness of the Chinese decision-making approach will necessitate the use of Chinese experts and contacts to make headway.

![]()

9-2 Korean Airlines: Biggles Does Korea

Flying from London to Seoul on Korean Airlines turned out to be a very interesting cultural experience for Tony Smith. Predictably for such a long flight (some 13½ hours), the aircraft was a Boeing 747, and in Korean Air livery. Passengers were greeted in Korean and English by smart and courteous cabin staff, in neatly pressed blue and white uniforms. Clearly the cabin crew was of Asian origin but while seated on the plane, awaiting takeoff, it was hard (for a Westerner) not to note the many unusual clues on-board as to the Asian-ness of the aircraft and its service.

However, after the aircraft took off, and after being lulled into this authentic Oriental ambience, Tony was suddenly subjected to a rude awakening as a clipped English public school accent punctured the air: “This is Basil your captain here. Spiffing weather today at our cruising altitude of 32,000 feet. Hope you enjoy the flight. Toodle pip!” It was hard to fathom. Surely, nobody today actually speaks like that – it was as if Biggles, the 1920s fictional flying ace, was captaining the aircraft!

The rest of the flight continued in this rather bizarre fashion, with cabin staff moving quietly, efficiently and discreetly around the aircraft while abrupt “English toff” style interjections periodically came from the flight deck. In attempting to make sense of this incongruous mixture, Tony determined that Korean Airlines might be using a tape recording to make English speakers feel more at ease. However, in attempting to make the commentary as English as possible, they had alighted upon a rather over-dramatic actor for impact. Why would the airline have gone to such trouble?

In the late 1990s, people became increasingly concerned about the poor safety record of Asian airlines. Of the five airlines that have had four or more serious crashes in the last decade, four of them are Asian. And researchers identified Korean Airlines as having the world’s worst safety record. The airlines with the best records were mostly from Anglo-Saxon English-speaking countries like Britain, Australia, Canada, Ireland and, particularly, the USA. In 1998, The Times ran a story on this research with the headline “Asian Culture Link in Jet Crashes”. One can begin to understand why an Asian airline might want to promote Anglo influences.

However, things may not be as clear as the first cut of the data might suggest. One London-based expert specialising in risk assessment claimed: “It is notoriously difficult, even misleading, to try to draw meaningful conclusions from ‘snapshots’ in aviation.” And many commentators are quick to point out that the Japanese, with a similar socio-cultural background to some of the worst performers, have one of the world’s best safety records. Despite these warnings, some analysts have begun to look at the extent to which national cultures affect pilot performance by comparing flight data with cultural characteristics.

Research done by Dutch academic Geert Hofstede in the 1970s and 1980s demonstrated that Asian nationals scored higher on dimensions of collectivism, power-distance and uncertainty avoidance than their Western counterparts. Those groups that score high on collectivism recognise their interdependent roles and obligations to group consensus, aspects indicative of a “strong” culture. Those on the high end of the power-distance scale expect and accept that power is distributed unequally, accept the necessity of hierarchies, and are less likely to challenge authority. Members of high uncertainty avoidance cultures prefer rules and set procedures to contain and resolve uncertainty, whereas low uncertainty avoidance cultures tolerate greater ambiguity and prefer more flexibility in responding to situations.

Aviation researchers have identified that total reliance on the autopilot facility is dangerous in potential crash situations, that captains can make fatal errors of judgement that can often be corrected by other crew members, and that the speed and decisiveness of decision-making is usually vital. A more recent study carried out by psychologists from the University of Texas indicates that 100% of Korean pilots claim to prefer deferring to the autopilot and always used it (the highest percentage of the 12 countries surveyed), and showed greater shame when making a mistake in front of the crew than pilots from other countries.

9-3 Banque du Sud: Building a Pan-Regional Actor?

In 2005, Banque du Sud (Tunisia) was acquired by AttijariWafa Bank (Morocco). This was the first time in the Tunisian privatisation process that there was an acquisition into Tunisia from a south Mediterranean country (i.e. Morocco). The stated aim of this acquisition was to develop different synergies between Morocco and Tunisia in terms of expertise and know-how.

The Tunisian economy has seen sustained rises in GDP over the last few years (see Table 9.1) largely as a result of greater engagement with the global economy and through adopting policies designed to promote free competition with foreign markets. For example, the Investment Code 1994 substantially improved, standardised and codified incentives for foreign investors. Wealth in the economy at the national level has allowed the funding of large infrastructure projects in particular, and at the individual level has increased the purchasing power of Tunisia’s upper and large middle class.

Table 9.1 The Tunisian economy (Tunisian dinar = TND)

| GNP constant value | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 |

| (TND millions) | 19,348 | 20,517 | 21,384 |

| GNP growth rate | 5.6% | 6.0% | 4.2% |

| Inflation rate | 2.4% | 3.6% | 2.0% |

| Investment (TND millions) | 7,536 | 7,913 | 8,410 |

| Savings (TND millions) | 7,122 | 7,799 | 7,968 |

| Exports | 10,342 | 12,054 | 13,607 |

| Imports | 14,038 | 15,960 | 17,101 |

| Tourism revenue | 1,902 | 2,290 | 2,564 |

The signing of the Agadir Agreement for the Establishment of a Free Trade Zone between the Arabic Mediterranean Nations (Tunisia, Jordan, Egypt and Morocco) in Rabat, Morocco in February 2004, aims at establishing a free trade area as a possible first step toward establishing a Euro-Mediterranean free trade area. This agreement is widely perceived as a likely driver for regional business development and may also result in the modernisation of sectors.

For some time, the Tunisian Government has been actively encouraging selected foreign direct investment (FDI), particularly for export-oriented industries. It screens potential FDI to minimise the impact of the investment upon domestic competitors and employment.

A large part of this FDI has been from Tunisia’s privatisation programme which sells off state-owned or state-controlled firms. The programme began in 1987 with the sale of the smallest and least viable public sector enterprises, but now includes major state assets such as Tunisie Télécom and there has been partial sale of the national petroleum distribution company (SNDP), the State automobile manufacturer (STIA), and a planned sale of 76.3% in Magasin Général, the Government’s 43-store supermarket chain. Every year the Ministry of Development and International Cooperation and the Foreign Investment Promotion Agency (FIPA) hold an investment promotion event, the Carthage Investment Forum, to introduce Tunisian business opportunities to global investors. In 2006, total FDI amounted to US$15bn, contributed to the creation of over 2,600 companies and some 250,000 jobs. Total FDI in 2005 was US$750m.

The largest single foreign investor to date in Tunisia is British Gas, developing an offshore gas field for US$1.1bn. Many of the world’s largest multinational enterprises (MNEs) are also invested in Tunisia, i.e. Siemens, Sony, Philips, Pirelli, Fiat, Nestle and Citibank. Spain continues to be a big investor in Tunisia and, in order to achieve a more level playing field for US companies, the US has begun a process of establishing a Free Trade Agreement (FTA).

The mobilisation and allocation of investment capital is still hampered by the under-developed nature of the local financial system. The stock and bond markets find it hard to attract investor interest and are currently flat. Foreign investors can purchase shares in Tunisian firms but they have to do this through authorised brokers or indirectly through established mutual funds. Capital controls are still in place.

The banking system is considered generally sound and is improving as the central bank has begun to enforce adherence to international norms for reserves and debt. Recent measures include strengthening the reliability of financial statements, enhanced credit risk management and improved creditors’ rights. There are now tighter rules on investments and bank licensing and the required minimum risk-weighted capital/asset ratio has been raised to 8%, consistent with the Basel Committee capital adequacy recommendations. Today 13 of the country’s 14 banks conform to this ratio (compared with just two in 1993). Despite these strict new requirements, many banks still have substantial amounts of non-performing or delinquent debt in their portfolios. The Government has established debt recovery entities to buy up these non-performing debts but there is no information on how successful this has been.

Despite privatisation, the Government remains dominant in the banking sector, controlling 11 out of 20 commercial and development banks. However, foreign participation in the capital of banks has risen significantly and now stands well over 20%.

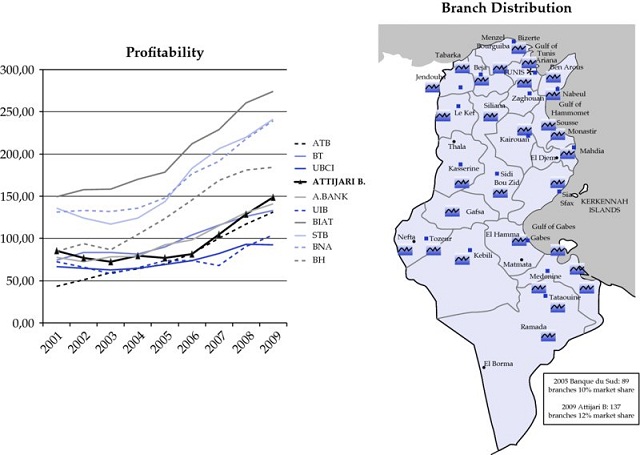

The Banque du Sud was set up in 1968 and at the end of 2005 had a registered capital of 100 million dinars (US$ 1 = TND 1.25 approximately). The bank had 89 branches throughout Tunisia and held a 10% market share. Turnover in 2002 was TND 129m, resulting in after-tax profits of TND 10.2m. It was recognised at the time that Banque du Sud had a substantial branch network and a large and diverse customer portfolio. It had a large presence in international trade and this offered significant potential for future development. Banque du Sud was engaged in every customer segment but it also had a high proportion of doubtful or uncertain credits and its ratios had been declining for some time as the competition in the banking sector was increasing. Although the bank was in a poor financial situation it did have devoted employees. However, the management of these human resources appeared weak with bad communications and poor or old systems. For instance, there were no assessment systems to evaluate the competency and skill of employees. While under state control the level of investment in information systems had been low and there had been little need for clear direction for the bank. However, now, with a deregulating economy and the likelihood of increasing bank regulations in the future, the Banque du Sud faced a major challenge.

By international standards, Morocco’s banking system is reasonably well developed and regulated. Recently consolidations have resulted in six large banks (Attijariwafa, CPM, BMCE, BMCI, SGMB and CDM) controlling 80% of loans and 88.3% of total deposits. The banking sector is divided into four categories:

- Deposit-taking banks: the five large privately owned banks; Attijariwafa; BMCE; BMCI; SGMB; CDM

- Crédit Populaire du Maroc: a mutual company and the leader in deposit-taking from Moroccans living abroad (the State is the majority shareholder)

- Specialised financial institutions: CIH; Crédit Agricole du Maroc

- Niche banks: Bank Al Amal; Media Finance; Casablanca Finance.

Foreign banks are strongly present in the private banks holding significant share stakes, e.g. BNP Paribas controls 65.1% of BMCI; Société Générale de France owns 51.6% of SGMB; Grupo Santander holds 14.6% of Attijariwafa.

With assets of 146.8 billion Moroccan Dirhams (MAD) (equivalent to US$16.7bn with MAD 8.8 = US$ 1, as at 30 June 2006), AWB is Morocco’s largest private sector bank. Attijariwafa Bank was formed in June 2004 in the course of the restructuring of the banking sector by a merger of Wafa Bank and Banque Commerciale du Maroc. With over one million customers, the bank claims a domestic market share of some 25%.

AWB is listed on the Casablanca stock exchange and is the second largest firm by capitalisation. It is fully owned by private Moroccans and foreign investors. The biggest stakes are held by Groupe ONA (33.1%) and Banco Santander (14.6%). Groupe Ona is controlled by the Moroccan royal family.

AWB is a Universal bank with strengths in corporate banking and subsidiaries in consumer and mortgage lending (where it has 27% and 20% of the market respectively), leasing, factoring, asset management and investment banking. AWB has a domestic branch network of 540 branches. AWB also has a presence in Senegal (it acquired Banque Senegalo-Tunisienne in late 2006) and is currently looking to expand into Algeria. AWB has a presence in Europe through a 100% owned subsidiary and this gives good access to Moroccan expatriates. They have 360,000 customers with total deposits of MAD 24bn as at 30 June 2006.

Since its merger with Wafa Bank and tougher economic conditions in Morocco, AWB has had to book large provisions over the last three years but, since 2005, higher credit volumes, stronger earning diversification and better cost control have improved profitability and asset quality. AWB is now well placed in retail banking to capture additional earning streams from the emerging lucrative consumer banking segment in Morocco. This should help to reduce the bank’s concentration for risk in corporate lending. The bank’s funding and liquidity profile is strong due to good access to retail deposits, including Moroccan expatriates and large government bond holdings.

AWB has completely rethought its organisational structure to place the customer at the heart of its concerns in order to enhance cross-selling, to improve levels of service and to develop specialist expertise. The group is organised now in six independent business units each with its own resources. The main guiding principles are to: strengthen management; develop a performance driven culture; encourage employees to take more responsibility; increase powers of delegation; make the execution process more professional by better internal controls.

AWB has two main objectives:

- Enhance the bank’s position in Morocco, especially in retail and small and mid-sized enterprise segments as well as investment banking.

- Strengthen its position outside of Morocco, mainly in the expatriate segment but also North and West Africa.

AWB plans to increase its branch network to 900 branches and 2.5 million customers by 2010 and wishes to control one third of the Moroccan mortgage and personal loan segments. AWB plans to consolidate its relationship with large firms, and enhance cross-selling and fee-rich transactions – this might help improve the quality of its loan portfolio and profitability.

To develop its strong position outside of Morocco, AWB plans to further enhance its share of expatriate business through its French subsidiary. It already has 26.4% of expatriate deposits which provides AWB with a comparative advantage. It also intends to expand its mortgage business by offering loans to customers wishing to purchase property in Morocco. Having an international presence helps AWB to serve the needs of some of its larger clients. AWB has a more developed appetite for expansion in North and West Africa than its competitors but its presence in these countries has never been tested by an economic downturn. The credit culture in these countries remains weak and there could be problematic exposure to credit and foreign exchange risk.

In 2005, Attijariwafa with Santander bank acquired 53.54% of Banque du Sud capital, in Tunisia, as part of its expansion plan. Approximately US$45mn was paid for the State’s 34% share of the bank’s capital and a further 17% was purchased from a private Tunisian group. “We and our strategic partner Santander bought the stake from the Tunisian government under privatization,” said Wafa Guessous, Attijariwafa Bank’s Public Relations Manager. “We want to make Banque du Sud a leader in retail banking and in financial and trade flows between Morocco, Tunisia and Spain,” she added.

The new Managing Board of the bank now ordered an exhaustive audit of the acquired bank to identify priorities and to strike a balance between shareholder, customer and wage earner interests. They aimed to create a strategic plan that would make the bank a “famous local actor”. Through this plan the bank wants to participate in the economic development of Tunisia and to adopt the logic of economic cooperation between Maghreb countries. However, despite these well-intentioned broad aspirations, the Board knew it had to take specific actions in order for the acquisition to be successful. There were questions to consider about all aspects of the business. Who would lead it? How would know-how transfer actually take place? How would AWB really benefit from the acquisition? Why did AWB think it could manage Banque du Sud better than it had been managed before?

Figure 9.7 Tunisian banking industry: comparative data

9-4 Red Cross/Red Crescent: Humanitarian Movements and Boundaries

The Red Cross is one of the world’s most recognisable symbols alongside corporate brands like Ford, Coca-Cola and Apple. However, the organisation that it symbolises is not a single multinational structure under the command of a CEO and Board of Directors. Indeed, the often-heard “International Red Cross” is something of a misnomer as no official organisation bearing that name actually exists. Rather the Red Cross “Movement’s” nearly 100 million volunteers and 12,000 full-time staff spread around the world are coordinated by a number of distinct and legally separate organisations that are united by common basic principles, objectives, symbols and statutes.

At “the sharp end”, as it were, is the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), a private humanitarian institution whose 25-member committee has unique authority under international humanitarian law to protect the life and dignity of the victims of armed conflicts. The ICRC is the lead organisation in coordinating humanitarian relief in armed conflict situations.

On the ground are the 186 national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, each of which works in slightly different ways according to their specific circumstances and capabilities but all of which are united by the Movement’s seven fundamental principles, which are summarised below:

- Humanity: We act to prevent and alleviate human suffering wherever it may be found; to protect life and health and to ensure respect for the human being; to promote mutual understanding, friendship, cooperation and lasting peace among all peoples.

- Impartiality: We relieve the suffering of individuals, being guided solely by their needs, and to give priority to the most urgent cases of distress.

- Neutrality: In order to continue to enjoy the confidence of all, the Movement may not take sides in hostilities or engage at any time in controversies of a political, racial, religious or ideological nature.

- Independence: The National Societies must always maintain their autonomy so that they may be able at all times to act in accordance with the principles of the Movement.

- Voluntary service: A voluntary relief movement not prompted in any manner by desire for gain.

- Unity: There can be only one Red Cross or one Red Crescent Society in any one country. It must be open to all.

- Universality: The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, in which all Societies have equal status and share equal responsibilities and duties in helping each other, is worldwide.

Under the Geneva Convention, relief workers from National Societies bearing Red Cross and Red Crescent authorised symbols are protected under international law and must be granted free access to people in need of help.

And, in the middle of the Movement, there is the IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies). The IFRC manages and coordinates the activities of the National Societies. It is also the lead organisation in missions not related to armed conflicts and organises interaction and cooperation with the ICRC. The IFRC is primarily funded by contributions from the National Societies. Its executive body is a secretariat led by a Secretary General supported by four division heads, but the highest body in the IFRC is the General Assembly which convenes every two years with delegates of all the National Societies.

The Red Cross Movement began in 1862, when Geneva businessman Henry Dunant had a global idea. The resources of the many Red Cross Societies that had emerged in different countries by this time could be pooled to provide humanitarian assistance in peacetime and not just to provide medical aid in times of war. Dunant wrote that “[t]hese Societies could also render great services, by their permanent existence, in times of epidemics, or of disasters such as floods, fires or other natural catastrophes”.

Further impetus was given to this idea by Henry Davison, President of the American Red Cross War Committee. In December 1918, responding to US President Woodrow Wilson’s call for ideas as to how the world might be better managed after World War I, Davison proposed a league of the world’s Red Cross Societies as a parallel to the League of Nations that Wilson had advocated. On 5 May 1919, the governors of the Red Cross Societies of France, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States signed the original Articles of Association.

Perhaps the thorniest issue for the IFRC as it has expanded its reach relates to its identity, or what a for-profit organisation might more readily call its “brand”. The red cross on a white background was the originally adopted symbol declared at the 1864 Geneva Convention. In terms of its colour it is a reversal of the Swiss national flag, a meaning that was adopted to honour the Swiss heritage of Dunant and the Movement.

However, this symbol raised issues as early as 1876 when members of the Turkish Society took the view that the red cross (redolent of the Christian Crusades in medieval times) would alienate Muslim soldiers during the Russo-Turkish war and adopted the Red Crescent symbol as an alternative. When asked by the ICRC, the Russians agreed to respect the sanctity of people under the Red Crescent banner and the Ottomans reciprocated by accepting the sanctity of those operating under the Russian Red Cross. After this local declaration of the equal validity of both symbols, the ICRC declared that it should be possible to adopt an additional protection symbol for non-Christian countries, and the Crescent was formally adopted in 1929 when the Geneva Conventions were amended. Currently the Red Crescent is the symbol used by 33 of the Movement’s 186 National Societies.

However, wary that further proliferation of symbols could be problematic (both in terms of the unity of the Movement and of people being able to recognise and respect those acting under its banner and its principles), the ICFC and the IFRC have since rejected a number of further applications to incorporate different symbols into the Movement, such as the Red Archway proposed by Afghanistan in 1935, the Red Lamb proposed by the Republic of Congo in 1963 and the Red Wheel proposed by India after Indian independence. In such instances, following the rejection of their claims, each of the National Societies concerned has agreed to use either the Red Cross or the Red Crescent as their symbol.

More problematic, though, was the Israeli Society’s (known as Magen David Adom – MDA) Red Shield of David. The ICRC and the IFRC’s rejection of the Red Shield (in the shape of the Star of David) and MDA’s desire to keep it, led to the ICRC and IFRC not officially recognising MDA as part of the Movement for many decades. In protest at their exclusion, the American Red Cross Society had been withholding its financial contribution to the IFRC since 2000. By 2008 this had amounted to US$45m.

The impasse was only resolved in 2008 when an alternative third symbol, the Red Crystal (effectively a red diamond shape in outline) was proposed and voted in by over the required two-thirds majority by delegates at a Red Cross and Red Crescent assembly conference. At the same time Magen David Adom and the Palestinian Red Crescent Society (which had been excluded previously by the statute requiring that only societies from sovereign nations be allowed to join the IFRC) were officially admitted to the Movement.

The Red Crystal can be used by any relief teams in areas where there is sensitivity about Christian or Muslim symbols. Members of MDA will be able to work across borders under the Red Crystal banner. On their own territory – or with the agreement of other states participating in relief operations abroad – they will be able to fly a flag with the Red Shield of David within the Red Crystal shape.

Discussions are now taking place as to whether other National Societies may use their own local symbols within the Red Crystal on their home territories.

9-5 HSBC: The World’s Local Bank

From humble beginnings as a regional bank established in 1865 to finance international trade along the coast of China, HSBC (Hong Kong Shanghai Banking Corporation) has grown astronomically over the past decade. It has grown both organically and through astute acquisitions to become one of the world’s biggest companies. From its early history as a collection of banks connected through British Empire or Commonwealth ties (early principal members included The British Bank of the Middle East, The Saudi British Bank and the Cyprus Popular Bank), HSBC now employs over 200,000 staff based in 87 countries and territories. The recent growth spurt can be traced to 1991, with the formation of HSBC Holdings, a holding company for the entire group with its headquarters in London and its shares quoted in London, Hong Kong and New York.

Unusually for a company of its size, however, HSBC has always championed the importance of local diversity rather than the importance of scale. In the words of Group Chief Executive Stephen Green, “We do not aspire to be a unicultural company.” This is down to the belief that, according to former Group Chairman John Bond: “People do not appreciate the one size fits all approach commonly associated with global corporations.”

But how do you continue to grow and coordinate and focus a company that operates across so many borders? One way was to adopt a unified brand. This brand, featuring the letters HSBC next to a red and white hexagon (a stylised version of the original 19th-century HSBC flag based on the cross of St. Andrew) was launched in 1998. Within a couple of years, this symbol and the letters HSBC were well recognised, but according to HSBC’s then Head of Marketing, Peter Stringer, people were not really sure what the letters stood for. They weren’t sure about the values or the character behind the HSBC name and symbol.

At around this time, a group of UK-based HSBC executives on an executive development programme settled down to discuss the ethos of their corporation and its current strategy. As part of an exercise they began to think of HSBC in terms of its personality. In other words, to think on the question: “If our company was a person, what kind of person could it and should it be?”

While this was not an easy task, one thing that surfaced very quickly in the ensuing discussion was that these executives were sure that one of their leading competitors had recently got its “personality” all wrong. Barclays Bank had just launched a media campaign extolling the virtues of its “bigness”. Celebrities like Anthony Hopkins and Robbie Coltrane told the camera that “people want things ‘big’ – and they want a big bank”. According to the HSBC executives, while people may have wanted some of the benefits that a big bank offered, they also liked the idea of dealing with a bank that “felt” small and valued particular personal relationships.

Eventually, having split themselves into three smaller groups, each group came up with a possible personality: James Bond, the current CEO of the Bank and Michael Palin.