2

Macro-Shocks

He who is best prepared can best serve his moment of inspiration.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

25 June 2016, managers in Shanghai China were dismayed to learn that their wages had just fallen by 14% in one hour! The reason – the UK had just decided by a slim margin to leave the European Union in what has become known as “Brexit”. Although this might have appeared to be a local issue about who governs the UK, the British people or a European bureaucracy, the ramifications of the vote were immediate and global. Currency markets saw the value of the pound fall against all other currencies and the price of gold rose. Stock markets fell around the world reflecting this new uncertainty, not only for the UK and Europe, but also their other trading partners. In the run up to the election, organisations had held off investing in the UK as it was unclear whether the vote to leave or to remain in Europe would prevail.

Now the vote had happened, businesses had to make strategic decisions in the light of this seismic change. The changing context was already affecting organisations in different ways, with some UK businesses benefiting from the fall in the value of sterling, making their exports more competitive and those relying heavily on imported resources seeing their cost base rise, making them potentially less competitive. Foreign organisations with UK-based operations, such as Nissan, were fearful that Europe might impose tariffs on their products and services and banks such as JP Morgan Chase and HSBC were talking about relocating some of their operations and thousands of jobs to continental European countries.

Brexit was also having widespread effects on organisations further afield. The prospect of the UK going it alone was enthusiastically greeted by former colonies, such as Canada, New Zealand and Ghana, and countries such as Mexico where organisations actively campaigned to have trade deals with the UK. The idea of Brexit was also being seized upon by nationalist parties in Europe seeking to distance themselves from Brussels and even by Donald Trump’s Presidential campaign announcing a “Brexit plus plus plus” in order to “make America great again”. His victory on 8 November was seen as tumultuous for the USA and, as with the UK Brexit, threw markets and organisations into great uncertainty. Neither event was expected but the resulting massive uncertainty was forcing organisations to re-evaluate their strategic situations in the light of potential positive and negative influences. What should their strategies be now?

One reason for the intensity of the UK Brexit shock and the unpreparedness of so many organisations was that it was widely believed, by the vast majority of politicians, the media, intelligentsia and leaders of major organisations, that the UK public would vote to remain in Europe. Even the Government of the time had no “plan” for what to do as a result of a vote for leave – indeed for months afterwards the new British Prime Minister, Theresa May, was constantly attacked as having no plan for the economy. Another reason for organisations not being prepared was a lack of precedent as the UK was the first country ever to leave the EU. A further complication was that the Brexit vote was not binding on the British Government and the Law Lords had argued that Members of Parliament could vote differently from the wishes of the British people – which would create a constitutional crisis. Until the British Government formally triggered Article 50, nothing would change with Europe, but after that there would be just two years to negotiate the terms of withdrawal. This would be highly complex. There would be multiple EU institutions to contend with and, if the agreement was to be broad, including not just trade but also security and foreign policy, then all 27 countries had to find agreement. If no agreement could be reached between the UK and the EU then all treaties under which the UK is governed by the EU would be dissolved.

Organisations therefore had to consider what to do in response to the vote, the likelihood of British politicians breaking with Europe, the agreement(s) that might, or might not, arise between the UK and Europe and the time frame in which this would all be acted out. Organisational strategists had to think through possible future scenarios and contingency plans. Whatever the eventual shape and implications of Brexit, it was a major, largely unanticipated event with shock waves resounding around the world, impacting on peoples, organisations and institutions across multiple geographic regions, with differing intensities at different times.

Brexit is an example of what is called a macro-shock: a major event in the broad context within which organisations are embedded, and over which they can exert little, if any, control. While the Brexit vote was widely anticipated, the outcome was a surprise. Sudden unexpected major contextual changes grab attention as they excite major reactions from a wide range of stakeholders (witness the media frenzy surrounding the BP oil leak in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010). These sudden breaks with the past might be described as “inflexion points” where past trends change markedly, invalidating previous forecasts. However, macro-contextual change may also be more gradual in nature. For instance, the biggest challenges facing humanity are identified as global warming, ageing and growing populations, declining fossil fuel reserves and species extinction. Even though they are gradual, these so-called “megatrends” are major challenges forcing organisations to adjust or perish.

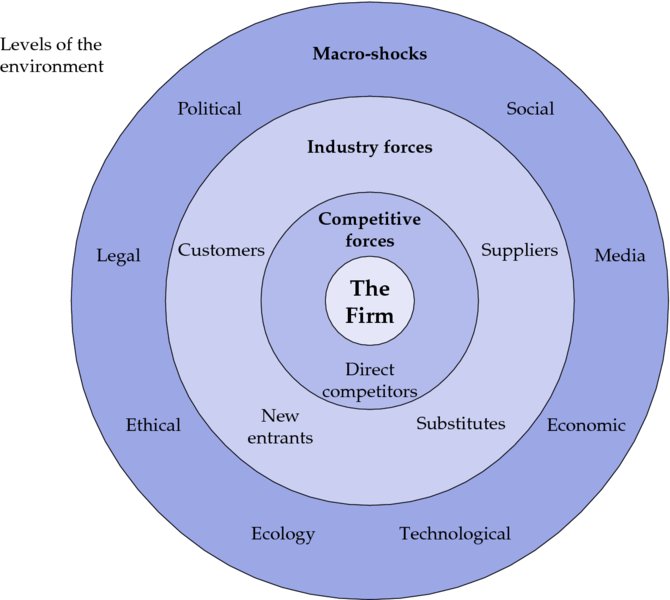

Consequently, the primary pathway toward better strategy development may be the realisation that organisations and their strategies do not operate in a vacuum. They are open systems that take resources and information from the environment and transform them into products and services that are fed back into the environment. This open systems perspective emphasises the interconnectedness of the firm and multiple levels of the environment. For instance, Australia’s mining industry is being negatively affected by the slow-down in demand from China. Some of these key forces in the organisational environment are illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 Some of the many interactions between organisations and their environment

(Source: Davis and Frederick, 1984)

Organisations are subject to a wide range of shocks from such forces. Institutional pressures from regulators, stock markets and governments can directly affect how industries and organisations operate; industry-level shocks and the actions of competitors, suppliers and customers (discussed in Chapter 3 Industry Forces and Chapter 4 Competitive Advantage), together with internal shocks (see Chapter 10 Managing Change), can all have major consequences for an organisation. However, this chapter focuses on the broad macro-environment beyond these levels, where organisations have little direct influence. From this “deterministic perspective”, which views organisations as constantly buffeted on the seas of change with managers often heroically attempting to keep the “boat afloat”, the key for strategists is to be what Coleridge called the “best prepared”. Best prepared to counter the strategic threats and grasp emerging opportunities in order to recalibrate, so that the strategic “dreams”, visions or inspirations that we described in Chapter 1 Strategic Purpose can still be achieved or adjusted.

The Impacts of Macro-Environmental Forces: The Role of Boundedness

Brexit has differential impacts on organisations and industries. For some organisations, the effect is direct and specific. Those UK organisations dependent on foreign imports have to decide whether to pass their rising costs to the consumer by increasing their prices, such as potato chip maker Walkers Snack Food Limited, or, for some food manufacturers, by reducing the size of packets while maintaining the same price. UK Airline organisations, such as Ryanair and Easyjet, have seen their profits hit whereas other organisations, such as GlaxoSmithKline, have seen their sales increase and Diageo anticipated that its profits will increase as overseas sales of whisky are repatriated to a weaker British pound. The fall in the British pound means that British organisations are now cheaper than before, eliciting takeover bids for iconic businesses such as ARM Holdings for £24.3bn (€28.6bn) by Japanese tech investor Softbank, and Unilever for £114bn (€134bn) by US giant Kraft Heinz. The social effects of Brexit may also affect UK organisations with an anticipated reduction in immigration. Already organisations are worried that they will not be able to cope with a shortage of both skilled and unskilled labour. The impact of Brexit also may have a direct effect on other non-UK industries, such as increased demand for holidays in the UK and growth in banking and manufacturing sectors on the continent, anticipating more difficult trading conditions between the UK and Europe in the future. For other industries, the effect will be indirect, emphasising the connectedness point made earlier. The potential relocation of banking organisations may affect the availability of finance for small businesses, for instance. Domestic B2B (business to business) industries with no foreign imports may not be affected directly by the weakness of the currency or the uncertainty regarding trading relationships with Europe, but may be affected if their customers are affected.

Macro-shocks may also have a delayed impact. Brexit will take years to work out and although some effects maybe realised fairly quickly, others may emerge only gradually. In some instances, the duration of the effect(s) can be short-lived; airlines may be able to adjust capacity quickly, firms may be able to reset prices rapidly; whereas for other organisations the effects may linger – universities are losing students and highly skilled staff due to uncertainty and these may be tough to regain.

The impacts of macro-shocks may also have unexpected consequences. Even very negative shocks can inadvertently stimulate innovation. For instance, Brexit appears to be encouraging previously unlikely trading relationships. Some suggest that the UK may be significantly reoriented towards the rest of the world – something that would not have been possible while part of the European Union. Arguably Brexit might stimulate reform in the European Union, which could be positive for all. In other types of macro-shock, such as the volcanic eruption that took place several years ago in Iceland, disrupting global flights, alternative technologies might be encouraged as a consequence (perhaps aircraft engine design may alter), institutions may revisit prevailing rules and regulations in order to safeguard organisations and customers in the future, and some organisations may benefit directly from the shock – ironically in the Iceland case, its tourism has experienced a boom, with visitors keen to see an exploding volcano.

Macro-shocks often reverberate for some time, triggering other after-shocks either in a literal sense or metaphorically. For instance, some suggest the UK Brexit had some influence upon the US election and also may influence subsequent elections in European countries. The characterisation of a macro-shock as an earthquake, sending a major disruptive pulse or pulses into the environment, may be appropriate for some types of shock, lending itself to linear analysis of consequences. The pulses, or ripples, may follow a predictable entropic pattern, allowing their consequences for the environment to be anticipated by a skilful strategist. On the other hand, where macro-shocks occur in a social system, such as Brexit, the decay effects may be different from an earthquake, and indeed may escalate, which would make the prediction of consequences altogether more complex.

In any event, macro-shocks do need to be interpreted with care as they can be ignored or distorted to serve “blinkered” corporate purposes. Emerging shocks, such as the credit crunch of 2008/9, could have been anticipated and used as an opportunity to carry out deep restructuring changes far earlier than actually happened. In this instance, organisations should not be viewed as entirely passive recipients of change. Top management teams, for instance, may be limited in their ability to understand environmental complexity and to perceive the need for change in their organisations. Less limited thinking and more forthright anticipation of environmental concerns could have lessened the effect of this Global Financial Crisis.

It is safe to say that most organisations did not anticipate or plan for Brexit, even though there had been deep-seated and growing resentment of European controls among the UK population for some time. Why should it be so difficult for organisations to predict an event like this even though it could harm them? Organisations may be limited in the way in which they perceive the world and potential threats. This cognitive limitation, or boundedness, may mean that they just do not perceive potential threats, as they focus too narrowly on their own activities. In addition, major events may have their origins in rather obscure and minor happenings. This is often known as the “butterfly effect”: that “the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil may set off a tornado in Texas”. In terms of Brexit, the flap of a butterfly’s wings might have been years of protests by UK fisherman about Spanish trawlers taking fish away from them and feeling constrained by regulation to do nothing about it except sell up and change industry, large numbers of dairy farms closing across the country as they could not satisfy European regulations and remain competitive, and growing anger about an open immigration policy that was perceived to be taking jobs away from UK citizens. These were not new signals and yet may be described as “weak signals” – unstructured and fragmented but persistent counter impulses to the norm that can begin to form patterns.

Edward Lorenz, in trying to predict weather patterns at MIT during the 1960s, is widely credited with recognising that very small differences in initial conditions are rapidly amplified by evolution into complex patterns. By rounding the numbers in his calculations, from six to three places, widely divergent trajectories arose rapidly in his predictions from reality. Such observed complexity has led to the term “chaos” being applied, implying that prediction of the future is impossible. Ian Stewart in his book Does God Play Dice?1 takes a more optimistic view, observing that chaos and order, rather than being polar opposites, are in fact intertwined so that irregular behaviour is governed by a deterministic system. Such systems are not truly random and so for small parts of the complexity some order can be determined.

Fortunately, not all macro-shocks fall into the category of being very difficult to predict. For instance, it is widely known that world oil resources are depleting rapidly and will cease to be a major energy source this century. This will be a huge shock to the way organisations operate and will require fundamental shifts in organisations’ strategy. However, organisations are aware of this coming change and in the automotive industry, incumbents Honda and Toyota are already committing vast resources to R&D to produce alternative ways to power cars such as the use of hydrogen cells, dual fuel engines and lithium-ion batteries. New organisations such as Tesla are predicated on the macro-shift to new energy sources. The interconnectedness of these organisations, as shown in Figure 2.1, could result in major changes throughout the entire value chain, from supplier relationships to customer perceptions of what makes a good car. In this instance, some firms are clearly anticipating a macro-shock and are adjusting to compensate for a new reality.

Detecting Movements in the Macro-Environment

It is widely believed that there will be widespread oil shortages in the future as the costs of extraction rise inexorably. However, some automobile manufacturers do not appear to be taking any substantial measures in anticipation of an impending oil crisis. This may in part be explained by individual organisations’ propensity for perceiving macro-shocks. As we shall see later in the book, organisations can be so bounded in their perceptions, often when they are at the peak of their success, that they fail to perceive, or through arrogance choose to ignore, changes and trends that do not fit their conception of how the world will be. Danny Miller has likened this situation to the Icarus Paradox, where the Greek boy, learning how to fly successfully with wings of feathers and wax made by his doting father, flew too close to the sun with disastrous consequences. Organisations that have successful strategies but which fail to adjust to a changing macro-context can suffer terrible damage and may even be doomed. For instance, digital camera inventor, Kodak, was determined to continue to promote photo film to the world, where historically it had made huge profits, even though there was a strong trend towards consumers buying digital cameras. The result was that their core organisation declined precipitously and they failed to promote the new technology, leading to the demise of the organisation. In the UK, Marks & Spencer was the greatest retailer in the nation’s history and yet failed to perceive, or at least acknowledge, changing social tastes and fashions in the high street. Profits crashed, its share price plummeted, swathes of senior executives “left” and the firm was subjected to a takeover bid.

Not understanding and adjusting to macro-environmental forces can be perilous for organisations. This therefore raises the question: how can organisations understand their macro-environment?

Ginter and Duncan provide a good example of this, describing tobacco organisation R. J. Reynolds’ activities in detecting the implications of the US Surgeon General’s report on the harmful effects of smoking. As the authors note: “The environment is not a very mysterious concept. It means the surroundings of an organisation; the climate in which the organisation functions. The concept becomes challenging when we try to move from simple description of the environment to analysis of its properties.”2

Organisations should thus engage continually in four activities, the first letters of which form the acronym SMFA:

- Scanning for warning signs, macro-changes and trends that will affect the firm

- Monitoring for specific trends and patterns

- Forecasting to develop projections of anticipated outcomes of those trends

- Assessing to determine timing and effects of macro-changes on the firm.

Analysing Macro-Environmental Forces

Which areas of the macro-environment should be scanned, monitored, forecasted and assessed? For the purposes of strategic analysis, and under what might be termed the “outside-in” analytical framework, the complexity of interaction of an organisation with its external environment may be decomposed into macro-environmental shocks, industry forces (consumers, suppliers, threat of new entrants, substitutes) and competitive forces (direct competitors). Generally, the focal organisation has the highest degree of influence in the centre of Figure 2.2 – where decisions are made about the firm’s strategies, resource policies and configuration – and this declines outwards across successive boundaries.

Figure 2.2 Conceptual decomposition of the business and its environment to structure strategic analysis

Adopting this outside-in approach is useful to avoid myopia, or seeing the world in the firm’s own image. A common conceptual tool for embracing the macro-environment is PEST analysis, which stands for political, economic, social and technological issues. The value of the technique is in identifying drivers for change in the broad context that could affect the firm’s industry and the firm itself. PEST is a process technique as it makes explicit how forces in the macro-environment will change over time, rather than offering a snapshot view – a criticism often directed at many other strategy frameworks. PEST’s other advantage is as a handy acronym that helps strategists avoid partial coverage of a large macro-territory. Indeed, it has been remarked that the worst failing of a strategist is not to see the whole picture, or the “elephant issue”! There can be a natural tendency for analysis to be skewed towards economic and financial issues, perhaps because they are more tractable (data may be more readily available and there are convenient tools and techniques available for their analysis) and there are significant institutional pressures to engage in this legitimating language. PEST and its derivatives (outlined below) offer an important protection against this bias. Good sources of data for its components can be found on the websites of the Economist Intelligence Unit (www.eiu.com), the World Bank (www.worldbank.org) and Organisation Environment Risk Intelligence (www.beri.com).

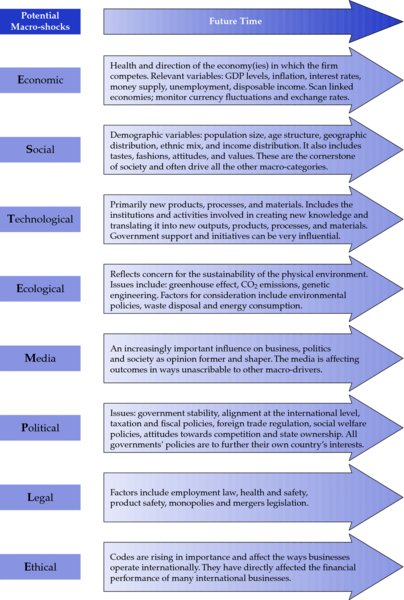

Since PEST was developed, other important macro-categories have emerged to reflect today’s more varied organisation environment. We have coined ESTEMPLE, which is illustrated in Figure 2.3, to incorporate these new categories.

Figure 2.3 Conceptual decomposition of the macro-environment using ESTEMPLE

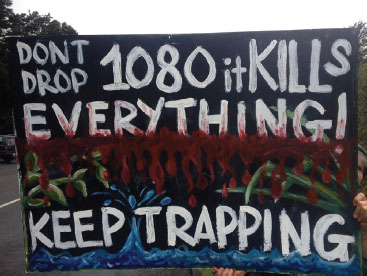

ESTEMPLE adds ecological, ethical, legal and media factors to our appreciation of the macro-context, reflecting a groundswell in current concerns regarding the sustainability of the ecological environment and the role of the firm in its management/ consumption (see Chapter 11, Evaluating Performance). Ecological concerns can now dramatically affect the health of organisations, such as the massive fall out in damages for BP after the Deep Water Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. Concerns over fracking in the US and UK are now leading to significant levels of public protest and levels of pollution in urban areas are seeing major changes in local policies that have widespread implications for communities and organisations. Ethical standards vary across borders and can be triggered by stakeholder actions (such as government intervention and investor sell-offs), altering codes of practice and influencing organisation decisions. Conflicting ethical standards can be very difficult for international organisations to manage. A growing body of research now shows that the media are an independent force, often supranational, influencing and shaping social opinion. For instance, national media are important in generating national solidarity and shaping perceptions of threat3 when, for example, foreign firms launch hostile takeover bids. Through dramatising risk to the loss of national resources, jobs, identities and culture, national media are defining the nation and mobilising the response.4 The influencing role of media is now directly acknowledged by newly elected President Trump who has debarred CNN, the New York Times and the BBC from an off-camera press conference and who has railed against fake news, saying it is a danger to the people.5 Media also includes social media that may allow crowds to influence others in dramatic and immediate ways. For instance, the Arab Spring uprising in Tunisia was communicated rapidly to neighbouring countries on people’s mobile phones and this may have potentially influenced subsequent actions. The importance of media is evident when markets are moved and corporate policies and actions influenced contrary to the dictates of rational economics. This has been observed in situations of financial bubbles such as the build-up of the housing bubble in the US.6

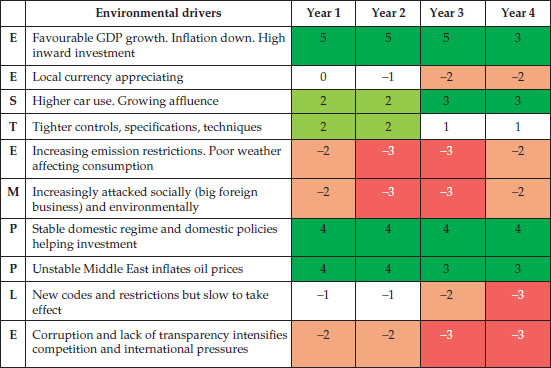

Identifying Key Macro-Environmental Forces

Clearly all ESTEMPLE issues are present continuously in the macro-context, but the important questions for the strategist are: which ones will be most relevant and will drive change in an industry, how might these change over time, and which of these factors, or collection of factors, will drive change for a particular organisation context? A first step to understanding which ESTEMPLE factors are most important is to construct a Temporal Impact Matrix (TIM) (see Figure 2.4). In this matrix, a list of key factors is made on the vertical axis and along the horizontal axis time periods are denoted appropriate to the industry.7 For each factor a positive or negative score is indicated for each time period. The scale for these scores can be determined by the user but the figure ranges from +5 for major positive effect to –5 for major negative effect. This score may also be weighted by likelihood of occurrence (for instance a major positive factor may have a +5 score but only a 10% likelihood of occurring, giving an actual score of +0.5). For visual impact, positive scores may be coloured green and negative scores red, as a heat map of opportunities (green) and threats (red). The resulting TIM will show quickly the main threats and opportunities in the macro-context for the organisation and also their timing. Where environments are largely predictable, organisations can plan for the future with confidence.8

Figure 2.4 Temporal Impact Matrix for the Moroccan Oil Industry

Notes:

The time periods in this matrix are yearly, but there could be a different unit of analysis to suit the context being analysed.

Note that some macro shock categories on the vertical axis occur more than once. This indicates that there may be more than one important factor in that category and it may be positive or negative.

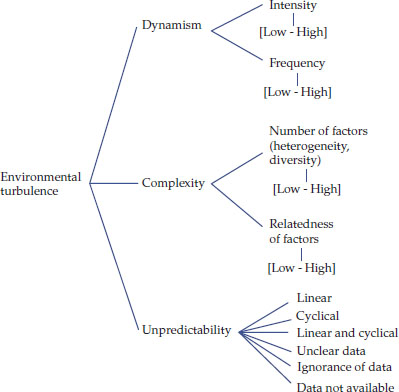

However macro-environments vary in their level of turbulence and this will affect the certainty to which a strategist may plan. For this reason, it is important for the strategist to determine the turbulence of the environment within which the strategic analysis is being conducted. Figure 2.5 shows that the turbulence of the environment can be conceived in three dimensions:9

- Dynamism (intensity and frequency of change)

- Complexity (number, relatedness and diversity of factors)

- Unpredictability (cyclicality of change and clarity of data).

Figure 2.5 Dimensions of environmental turbulence

(Source: adapted from Volberda, 1998)

Although an environment may be dynamic, with intense and frequent changes, this may not be a problem if patterns can be detected (and the data is reliable). In these circumstances, strategists can forecast the future and plan with some confidence. Hugh Courtney, Jane Kirkland and Patrick Viguerie in “Strategy under uncertainty”, published in Harvard Business Review, recognise that different strategy tools might be appropriate for different levels of environmental uncertainty.10 They show, in Table 2.1, that while forecasting might be appropriate in predictable environments, which they term “Clear enough future”, when it is difficult to detect a single pattern because some factors are not related, then forecasts are of less use and may even be harmful. In these circumstances, it may be necessary to engage in contingency planning, with a limited set of alternatives that a firm can follow depending upon how macro-events work out. These “Alternate futures” lend themselves to options analysis and can be seen in the Brexit situation described at the beginning of the chapter. Here, before the vote, it was clear that a number of banks were already planning for a binary outcome: (1) what to do if Brexit did not happen, and (2) what to do if it did? Where an environment is highly dynamic, very complex and unpredictable, organisations may not be able to decide and plan for specific options. In these circumstances, where there are considerable uncertainties that are likely to be highly important, scenario thinking11 is a useful technique. Royal Dutch/Shell is famous for its development of scenario planning techniques, and benefited from being able to anticipate the effects of the 1973 oil crisis by selling off its excess oil supplies before the worldwide glut in 1981. They developed a method for constructing detailed plausible alternative views about the future based on groupings of key environmental drivers and were able to develop a strategy to position the organisation effectively for the future. It is important to note with scenarios that they are not expected to materialise in the form envisaged (as this would then fall into options analysis) but a firm’s strategy should be assessed for robustness in the face of the scenarios created. It is also possible that the environmental context is so uncertain that even scenarios do not make much sense. In these circumstances, there are no bases for envisaging or planning for the future. In such situations of “True ambiguity” perhaps the only wisdom is to be prepared to react to whatever the context throws up.

Table 2.1 Appropriate strategy tools

| Clear enough future | Alternate futures | Possible futures | True ambiguity | |

| What can be known | A single forecast precise enough for determining strategy | A few discrete outcomes that define the future | A range of possible scenarios | No basis to forecast the future |

| Analytic tools | Traditional strategy tool kit |

Decision analysis; Option valuation models; Game theory; Scenario planning |

Latent demand research; Technology forecasting; Scenario planning |

Analogies and pattern recognition; Nonlinear dynamic models |

Adapted from Courtney, Kirkland and Viguerie (1997)

Developing Scenarios

In order to construct scenarios, the ESTEMPLE analysis should be revisited. All of the forces in the ESTEMPLE analysis should be assessed in terms of their level of impact and level of uncertainty (see Figure 2.6). Forces that have high impact and high uncertainty are suitable for scenario analysis.

Figure 2.6 Identifying environmental forces for a car manufacturer to construct scenarios

* Note that the ESTEMPLE consists of multiple forces of importance for some categories and none for others. This avoids the problem of assigning equal weight to each category in analysis.

** Forces are selected that are both high impact and high uncertainty. Forces that are high impact and highly certain should not be used as these can be planned for.

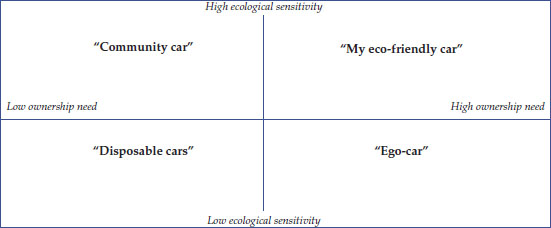

From Figure 2.6, it can be seen that there are four forces that might be suitable for scenario analysis. Two should be selected that are not correlated with each other to create the uncorrelated axes of a scenario framework. In Figure 2.7, the forces selected are ownership need and ecological sensitivity. The four scenario quadrants should then be labelled provocatively to stimulate thought.

- “Community car”: Cars shared by community members and not owned personally.

- “Ego car”: Most people have cars that represent their social status and self-image.

- “My eco-friendly car”: Eco-friendly but personalised cars.

- “Disposable cars”: Cars are cheap and freely available on the street.

Figure 2.7 Scenarios for a car manufacturer

For each of the scenarios, further description can be built in to further enrich the picture and to begin to consider some implications. In Figure 2.7 the scenarios are very much product centred but could be more contextual in nature. For the product-centred scenarios, “Ego car” implies high design values, high product variety and probably high variety in prices, unlike “Disposable car” where cheap non-descript cars may prevail, that do not require purchase but perhaps short rental periods. “Community car” suggests a degree of customisation based on socio-economic contexts and eco-friendly values, whereas “My eco-friendly car” suggests a wide range of vehicle types that all embody fuel economy and few by-products while being individually distinctive. Where organisations take the time to carry out scenario analysis in detail, they can then be populated with stories to make them evocative. For instance, what media stories might be headlines in the “Ego car” scenario – perhaps someone buying the fastest road car or one covered in gold leaf? For “Community car” it might be about the numbers of people using just one car. In some cases, organisations have even created newspaper headlines, created stories and even hired actors to act out situations in order to make scenarios seem plausible and real.

Once scenarios are created, managers can consider strategies that may be robust in the face of these different situations. For instance, what might BMW’s strategy be if faced with these four scenarios? The aim here (and to draw the distinction between alternative futures) is that scenarios should not be predictive of the future but be considered as plausible futures that allow managers to explore a set of possibilities and increase their perceptiveness of the key forces at work in the environment. Strategies can then be assessed in terms of their robustness in the face of the scenarios created.

Scenario thinking can be used to facilitate contingency planning and/or to work against the possibility of bounded thinking and the Icarus Paradox. For Royal Dutch/Shell, scenario development had two goals: (1) a protective goal to enable the firm to anticipate and understand the risks involved in doing its business, and (2) an entrepreneurial goal to discover new strategic options. In creating “macrocosms” Royal Dutch/Shell used scenarios as a fundamental aid to changing mental models of future opportunities and risk.12

Environmental analysis tools aim to improve the quality of executive decision-making. Some techniques, such as single-point forecasting, lend themselves easily to integration with central planning. Similarly, planning can cope easily with the identification of a limited set of future outcomes. However, managers are apt to confuse this with a set of multi-point scenarios, complaining that three or four forecasts are less helpful than one. This is to misunderstand the purpose of scenarios: full-blown strategies should not be developed for each scenario and then each tested against the other by some financial means such as Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) to see which scenario is the “best” (even if a management team were willing to do this). The temptation should also be resisted of assigning probabilities to scenarios as this is more the preserve of forecasting and would negate the exercise. Similarly, scenarios should not be thought of as good, bad or medium. The aim is to develop a set of scenarios against which the resilience of an organisation’s strategy can be assessed and management can be forewarned of possible vulnerabilities.13 Ian Wilson, in his article “From scenario thinking to strategic action” published in Technological Forecasting and Social Change, highlights how scenarios can be used to strengthen strategy formation and suggests four levels of sophistication from sensitivity/risk assessment for a specific strategic decision to the development of a strategy resilient to a wide range of organisation conditions. A fuller treatment of scenario development is contained in Van der Heijden’s classic work, Scenarios: The Art of Strategic Conversation.

Strategic Agility: Flexing with the Environment

As the world becomes increasingly interconnected, the ability of organisations to be agile and steer a path between rigidity and flexibility becomes a strategic imperative. Rigidity is often promoted by the drive for efficiencies in complex operations in stable environments, whereas responding “willy-nilly” to change can be a difficult characteristic for small entrepreneurial firms to shake off. Real problems can occur where macro-forces demand change and yet the firm is structurally rigid and therefore resistant to alteration.14 These structural rigidities impede change and may result in “strategic drift”, where the organisation begins to fall badly out of alignment with the changing organisation context.15 An example would be Kodak, once a world leader in photo film production and the inventor of the digital camera. Kodak failed to engage fully in a digital world due to internal rigidities that feared the loss of photo film revenue should digital camera development be pursued. The world moved rapidly towards adopting digital cameras and devices incorporating digital camera technology, leaving Kodak in terminal decline.

The most heavily used technique to assess this matching of the firm to its environment, to avoid drift, is SWOT analysis, in which a firm’s internal strengths and weaknesses are explicitly matched against external opportunities and threats. In revealing mismatches between the firm and its environment, strategic options can be generated to enhance the fitness of the firm.

It is critical to remember that SWOT is not just about generating lists of factors, as the analysis only has value if there is an explicit comparison, or fitting, of strengths against opportunities and threats and weaknesses against opportunities and threats. While many students and practitioners may well use SWOT as a starting place for their analysis, the technique has many weaknesses used in this way, not least the issue of how strengths and weaknesses are actually determined. For instance, what are the strengths identified relative to? In our experience, one way of avoiding long lists of strengths or weaknesses that don’t relate to the external competitive environment is to reverse SWOT into a TOWS analysis, whereby environmental threats and opportunities are examined before summarising organisational strengths and weaknesses. As you might expect in this chapter’s deterministic view of strategy (and this is contrary to other viewpoints expressed in later chapters), here the outside/in perspective is encouraged. In any event, SWOT/TOWS is best used as the culmination of other more focused analysis. So it may be useful to perform an ESTEMPLE analysis first and then plot out a Temporal Impact Matrix as a way of determining macro-environmental threats and opportunities. These can then be related to an organisation’s fitness through comparison with internal strengths and weaknesses (see Chapter 5). Furthermore, SWOT/TOWS analysis can summarise insights on different layers of the external environment in addition to macro-environmental concerns, and so can include influences from the industry and competitive environment, which we will cover in later chapters.

Underlying much of the discussion so far about the firm changing in response to/anticipation of macro-shocks is the notion of fit, or fitness of strategy. Much of the writing on the strategy of the organisation is the extent to which the firm “fits” with the context (cf. strategic gap analysis), or whether its “fit” will improve or deteriorate over time – a more dynamic view. This external consonance is important on the basis that misalignment will lead to firm underperformance. For organisational ecologists, firms cannot change easily because of structural rigidities and organisational routines (of which more later). Some large organisations, however, can and do exhibit strategic agility. Nokia of Finland, for instance, started life as a timber organisation, moved into white goods manufacturing, and then was hugely successful in mobile phones. Even now it is reinventing itself. However, such change is difficult, often requiring substantial alterations in competencies. Lou Gerstner is regarded as a brilliant strategist for having taught “the elephant” (a.k.a. IBM) to dance after its near fatal “Icarus” fall, where it failed to anticipate the decline in its mainframe organisation as desktop computing came to dominate. To some extent, the strategic issue for managers is whether the gradual change of an organisation – or “logical incrementalism”16 – is fast enough to accommodate step changes in the environment or macro-shocks. And “punctuated equilibrium” events like Brexit may always force radical and comprehensive change in an organisation or its demise.17

One of the most influential organisation books of the last decade is Competing for the Future by Gary Hamel and C. K. Prahalad. They argue that too many organisations focus on competing in the present and do not devote enough time to creating the future. They argue that organisations need to go beyond the static analysis of fitting their environment and instead should stretch and leverage their resources to redefine both the organisation and its context. For them, the key is not to anticipate the future but to create it. This suggests a philosophical shift from a more deterministic viewpoint, in which the macro-environment determines the success or failure of organisations, to an individualist, or voluntarist view where managers make a difference and can influence and shape the future context. For Gary Hamel: “The organisation that is evolving slowly is already on its way to extinction.”18 His solution is that evolution must be met with revolution. This discontinuous renewal perspective echoes Michael Hammer’s “Reengineering Work: Don’t Automate, Obliterate”,19 which advocates that managers should take bold steps and dare to accept high risk. It is an all-or-nothing proposition with an uncertain result.

In contrast, Masaaki Imai’s famous book, Kaizen: The Key to Japan’s Competitive Success, argues that continuous improvement best explains the competitive strength of so many of Japan’s organisations. This view stresses the importance of evolution and continuous learning. For Imai, Western organisations have an unhealthy obsession with one-shot solutions and revolutionary change. In our view, today’s strategists must be agile enough to recognise the virtues of both extremes. They should assess the particular organisations they advise in their macro-contexts, and create hybrid approaches that attempt to anticipate, analyse and influence the future, be aware and adaptive in the present to take advantage of opportunities as they emerge, and seek to be consistent in maintaining and building strengths that enable organisational fitness in a changing environment. While rare “Black Swan” events, defined as “the happening of the completely unexpected”, will always occur. This concept, popularised by Nassim Taleb, does not mean that the future is therefore completely unknowable and always negative. Foresight and agile configurations allow organisations to adjust and adapt to the unexpected and exploit positive potentials – not all organisations will fare badly from Brexit – and the explicit consideration of macro-drivers and strategic positioning can really work to an organisation’s advantage. To quote William Shakespeare’s Hamlet: “If it be now, ‘tis not to come; if it be not now, yet it will come – the readiness is all.”

Given this, those organisations and strategists that are “best prepared” and ready to adjust are more likely to win over the long term than those who are set in their ways.

Macro-Shocks Key Learnings Mind-Map

Having read and reviewed this chapter, outline what you believe to be the key learnings from the chapter and the relationships between these on the note pages below.

2-1 Broadwood and Steinway: Canoes versus Ironclads

John Broadwood & Sons, reputedly the oldest piano manufacturer in the world, was founded in London in 1728 and during that century made a harpsichord for the great composer, Handel. Later, in 1793, they abandoned harpsichord manufacture to concentrate on piano production. Indeed, in 1783, Thomas Jefferson, later to become the third President of America, came to discuss pianos with them. By 1843, Broadwood pianos were being used by the King of England and later Queen Victoria and the company was widely regarded as the greatest instrument manufacturer in the world. Admired for its association with the great composers, such as Ludwig van Beethoven, Chopin and Liszt, it had a highly skilled workforce and a reputation for producing the finest of pianos. But by the 1980s, the company was nearly bankrupt and although rescued, by 2000 it was just a shell company, outsourcing all piano production to Asia and licensing piano tuners for instrument maintenance. What had gone wrong for this world-class firm?

In 1851, there was an industrial census, which showed that Broadwood was one of just 12 factories in London, employing over 300 people. These craftsmen fashioned and adjusted by hand all the 3,800 pieces that went into making a Broadwood piano. The instrument consisted of a wooden frame strengthened by sophisticated wooden braces and some metal tension bars. This allowed the piano frame to take up to 16 tons of force from its strings, of which there was one per note. The firm produced around 2,500 pianos per year, which was 15% of total English production. Broadwood’s own output was 2.5 times greater than its nearest rival.

1851 also saw the Great Exhibition being held at Crystal Palace, London, where manufacturers from all over the world displayed their finest wares and competitions were held to judge which were superior. England exhibited 66 pianos, France, with producers such as Pleyel, showed 45 pianos and Germany displayed 26 pianos. The English efforts were rewarded with 12 medals, the French with nine and the Germans with eight. Unfortunately, the records documenting the number of gold medals are missing but, in numeric terms, the English pianos appear dominant. In 1867, a Broadwood piano was awarded a gold medal at the Paris Exhibition by Emperor Napoleon III.

At this time, two German brothers, Steinway, were attempting to introduce radical ideas on piano manufacture into Germany. However, the highly conservative and restrictive German guild system made it impossible for them to operate. They therefore decided to leave for America where they discovered a more sympathetic context and two innovations that were to revolutionise piano manufacture. To plough up vast areas of newly discovered land for agricultural purposes, the Americans had become highly skilled in casting ploughshares from iron. In addition, to remove the local Indian inhabitants, and to survive in the Wild West, it was necessary to develop a sophisticated handgun, the key feature of which, from the Steinways’ perspective, was a highly reliable, accurate and sensitive trigger mechanism. The Steinways adopted both of these innovations in the manufacture of their pianos. The cast iron technology allowed them to manufacture cast frames, and the handgun trigger arrangements allowed them to produce a highly sensitive and accurate key and hammer mechanism – a good example of a weapon being turned into an artproduct!

The advantage of the Steinways’ “American system”, as it became called, was that the cast iron frame could tolerate up to 30 tons of force from its strings. This allowed the use of much heavier strings, which could generate a far more powerful and richer tone as well as more compact pianos. This was particularly important for upright pianos, which, up until this time, had really been grand pianos on their side. The new hammer mechanism gave greater sensitivity to the pianist and its precise vertical movement greatly reduced the clatter of key mechanisms associated with pianos of that era. Overall these innovations also allowed cost savings of some 30%.

The next big piano exhibition took place again in London in 1862. Although the jury was accustomed to pre-Steinway sounds, two gold medals were awarded to Steinway pianos, one gold medal to a copy of a Steinway and one to a Broadwood as a souvenir des travaux passés. Nevertheless, the leading industry paper at the time, the London Musical Standard, wrote: “We [meaning the English piano industry] have no reason to dread competition in the manufacture of music instruments.” By now, Steinway had built a new factory in the US which boosted production from 500 to nearly 1,800 pianos per year. In 1873, the tables were completely turned on the English at the next big exhibition, which was staged in Vienna. England exhibited 12 instruments, France 34, and Germany 129. The Steinways’ American system was now adopted by all successful European firms and its dominance was epitomised in an advertisement at the time “as a MODERN IRONCLAD WARSHIP to a CANOE”. In 1880, in order to avoid import taxes and to tap into the European market, Steinway built a new factory in Hamburg, Germany, where they brought over their expertise in precision drilling. In 1883 even Franz Liszt was a convert to Steinway writing “it is a glorious masterpiece in power, sonority, singing quality and perfect harmonic effects”.

In 1878, at another exhibition, there was a modest square piano, which was barely noticed. It came from Japan and its makers were Yamaha.

A reasonable indicator of Broadwood’s performance in overseas markets can be seen in Australian import figures for English pianos from 1862 to 1902, among which Broadwood was the most prominent manufacturer. In 1862, Australia imported 100 pianos from England and just five from Germany. By 1886, imports from each country were running at similar levels of 230 per year. However, by 1902, over 500 pianos were being imported from Germany alone, compared with just 35 from England.

At this time, the managers of Broadwood were described as “sleepers” not “thrusters” and “gentlemen” rather than “players”. When one director died in 1881, he left a huge fortune of £424,000 and his obituary declared: “He took no share in the active portion of the business but was, however, an enthusiastic yachtsman.” A new board member, appointed in 1890, was educated at Cambridge University and Eton College. He was a keen farmer, oarsman and swimmer – “few could equal him at plunging”. He travelled extensively, “shot his tiger” but apparently visited no piano factories.

Some suggestions

Some suggestions

The ironclad versus canoe case shows the calamitous decline of the once world-beating firm of Broadwood. As such, it resonates with other major collapses in corporate history, such as the fall of IBM, Marks & Spencer and Rover Cars. The ways in which the “ironclad victory” case can be analysed is transferable to these other disasters.

1. Using an ESTEMPLE analysis, identify the macro-environmental forces for change in the piano industry.

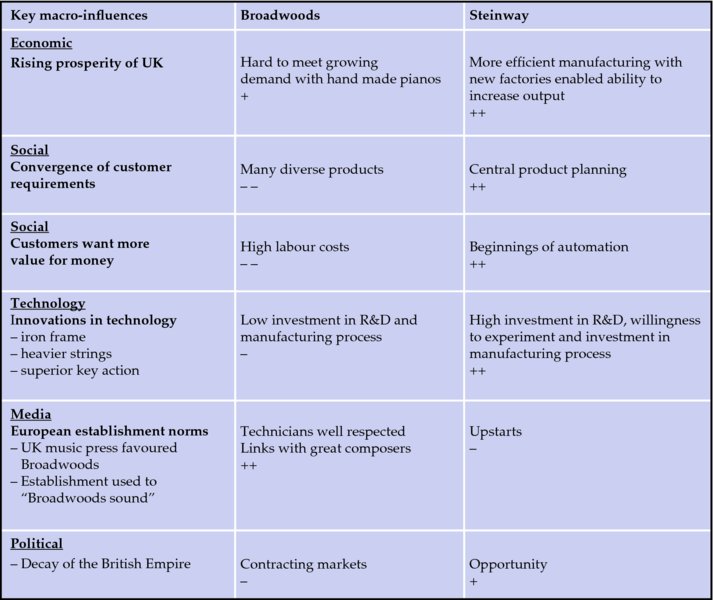

In assessing Broadwood’s evolution over time, we detect a slow but sustained drift away from its previously strong environmental fit. An ESTEMPLE analysis shows substantial changes in the macro-environment. Changes in technology in the agriculture and military industries began to be adopted in the piano industry, radically altering the way in which the piano was constructed. It was now possible to produce pianos with enhanced abilities at lower cost. The social context was also propitious. The Steinways found American society to be far more tolerant of their ideas than the German craft system. Their “American system”, with its greater volume and richer tone suited music being composed at the time, which relied increasingly on the rich sonorities of the instrument in complex harmonies and its percussive sounds. It is instructive that this new type of “romantic” music, pioneered by Beethoven some 50 years earlier, had now moved beyond the abilities of contemporary instruments, which he regarded as inadequate and lacking in powerful tone. Customers were also becoming more demanding, wanting more product for their money. Interestingly, one might argue that the media in the case are more backward- than forward-looking, and worked toward preserving the status quo and the maintenance of Broadwood’s reputation. It is possible that in this time of a weakening British Empire, there was some patriotism behind these sentiments. Politically and economically, the decline of the Empire at the turn of the century might be seen as a contributory factor in the decline in Broadwood’s export sales.

Against this shifting macro-context, Broadwood had barely changed its structure, competitive model or product. Indeed, it was very late in introducing a cast iron frame, as well as over-stringing, long after it had become commonplace in the industry. Broadwood hardly invested in R&D and relied heavily on its superior craft skills. Its management was passive rather than active, more interested in external unrelated activities, and not sensitive to a changing context. In this sense Broadwood displays sustained strategic drift.

Broadwood’s problem was that its original competitive advantage – a wide range of products with a highly skilled labour content – had become a structural rigidity. The new manufacturing methods and procedures introduced by Steinway struck at the very heart of the Broadwood model and undermined the value of their cherished assets. To move towards the Steinway system would have necessitated the removal of large amounts of skilled labour and the reduction in importance of many who remained in the company.

2. Construct an Impact Matrix to show how these changes affected Broadwood and Steinway.

A simple Impact Matrix (see Figure 2.8) shows the ways in which Broadwood and Steinway were affected by macro-shocks. It is clear that Broadwood had evolved little as major environmental shocks affected the industry. Steinway, however, had been able to capitalise on those changes in order to dominate the industry for over a century.

3. What conclusions can you draw about the effect of macro-shocks on organisations?

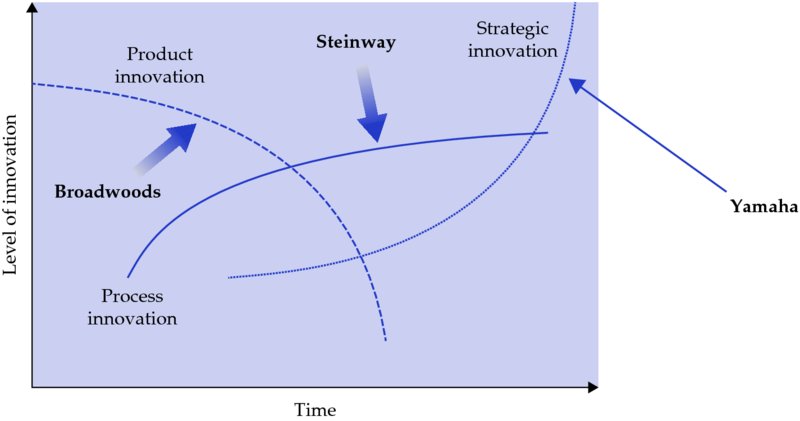

The change in competitiveness of Broadwood and Steinway suggest that as the world changed, one company was better able to adjust than the other. A model of industry evolution suggests that companies need to evolve in certain ways to remain competitive over time (see Figure 1.2). Here we can see that Broadwood stalled in a game of diminishing returns over product evolution as it failed to invest sufficiently in research and development and its costs of production became uneconomic. Steinway, however, pushed forwards into improving the manufacturing process, designing a piano that was cheaper to make (cast iron frame) and beginning a mass production process that quickly outperformed Broadwood’s hand-built crafts skill organisation. Innovating in the product and the process of production gave Steinway a significant advantage and later imitators soon overtook Broadwood who evolved too slowly. A late entrant into the industry, Yamaha then reconceived the nature of the piano as a keyboard that could have much wider application. This strategic innovation then gave Yamaha an advantage over Steinway in terms of the volumes of production that were now possible. Steinway failed to innovate in this way, becoming increasingly a niche provider of specialist high-quality pianos. The evolution of the industry can be seen in Figure 2.9.

Figure 2.8 Comparative Impact Matrix

Figure 2.9 Industry evolution

2-2 The French and British Armies: Stunning Victories and Defeats

The British Army’s numerous triumphs on the battlefield and distinctive red coat contributed to its outstanding reputation during the 19th century. The brilliant colour and gleaming steel exerted a strong psychological and emotional influence on its soldiers and on the enemy and was key in the exercise of British power. Coats were often trimmed with gold, silver or white lace depending on rank and carried between 20 and 40 buttons depending on the regiment. The headgear contributed to the striking appearance of soldiers, being imposing and topped with plumes. The British army was described by 19th-century commentators as superior in brilliance to any army in Europe with dazzling colour, a profusion of ornaments and polished accoutrements designed to present a stunning “coup d’oeil”. This martial spectacle of bedecked ranks of soldiers also communicated values of solidarity of purpose, discipline, conformity, order and efficiency. Many Britons took pride in the sight of the army as a symbol of Britain’s military superiority.

The British Army’s systematic use of red coats originated with Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army in 1645. Its popularity was probably due to the easy availability of red dyes and a simple dyeing process meant they were cheap to produce. However, they were now firmly established as the sign of an Englishman. During the American War of Independence in 1778, the American used camouflage so that they were difficult to see, unlike the massed British lines who were highly visible at the battle of Bunker Hill where they took heavy losses. Nonetheless the Redcoat persisted even though, by the 1850s, there was widespread adoption of rifles that allowed accurate long-distance fire and, in the 1880s, smokeless powder was introduced. The Redcoats were still in service during Britain’s major defeat in the Boer Wars in South Africa, although by now khaki (a light shade of yellow/brown) was being introduced in other fields of conflict such as India. Two hundred and ten years after its introduction into active service in 1902 the red coat was finally consigned to being of ceremonial use only, although it is worth noting that the French continued to use highly visible blue coats and red trousers up to the beginning of World War I where they sustained very heavy casualties.

The French had also clung to traditional ways much earlier in their history when their knights had dominated European battlefields for centuries. They were virtually invincible, with heavy armour, powerful weapons and considerable manoeuvrability. The massed ranks of knights were capable of ripping holes in enemy lines and intimidating advances. Their military power was echoed in the economic and political power of a French elite knightly class that had developed an elaborate code of chivalry and military conduct.

In 1346, however, King Edward III of England was conducting a successful campaign through Normandy where he had met little resistance. In moving his 8,000 men northwards to link up with Flemish allies, he was suddenly confronted by a far larger French army at Crécy. Edward arranged his forces around a hilltop from which he could observe the lay of the land. With his rear protected by forest and high ground, the enemy would try a frontal attack across open fields. To repulse the assault, Edward placed his yeoman archers to the fore. The English had learnt just how effective archers’ bows could be from bitter experiences in their border conflicts with the Welsh and Scottish. The English had begun to put this learning to good use by diverting a good portion of their increased wealth garnered from subduing their Celtic neighbours toward the development of technology such as the longbow. To encourage competence in the bow, competitions had been introduced around the English counties along with edicts making archery a compulsory activity. Subsequently, Edward’s longbow archers had an effective range of 300 yards, were able to hit a human target at 100 yards and could penetrate three inches of oak. With a direct hit, even armour would not deflect their arrows.

French lines were fronted with Genoese crossbowmen. Crossbow bolts could pierce the heaviest armour and these mercenaries could fire at a rate of two bolts a minute. However, despite the deadly nature of this weapon, the French nobility bitterly resented the ability of such “peasantry”. Indeed, in keeping with these beliefs, the French Catholic Church forbade the use of this “lowly” weapon by Christians against Christians. It therefore tended to be marginalised and underutilised in battle by the ruling classes. Behind the crossbowmen stood the armoured French knights on heavy warhorses supported by footmen. However, at Crécy, the narrow road to the battlefield was heavily congested. Supply carts and necessary equipment could not get through to serve the lines ahead.

The Genoese were the first to fire, but their volley fell short. Before they could reload and advance, the English let loose barrage after barrage of arrows. The Genoese, normally protected by large wooden shields, were vulnerable as most of their shields were still in the supply carts. Hundreds were killed, defenceless against the hail of arrows. A wave of French knights then charged over the Genoese ramparts, aiming to crash through the English line and break their formation. But they too were engulfed in lethal English arrows. Although the rounded surfaces on the French armour deflected the deadly tips, flat surfaces, chain mail and open helmets did not, and the horses, being much less well protected, fell with their riders. Once grounded, the French knights were virtually defenceless against the English footmen who slaughtered them with axes and daggers. The French made repeated assaults, but by the end of the day it was said that 16,000 Frenchmen had perished to England’s 300. The scale of the defeat was such that nearly every noble family in France was affected directly.

The new technology of the massed English archers had changed the landscape of war. However, the French responded to this blow to their pride and chivalry by investing further in armour. Chain mail was replaced by armour plate and warhorses also had armour plate covering vital areas. The plates became thicker and helmets had visors added. While their operational elements were reinforced, France’s strategic approach to warfare remained unchanged.

Almost 70 years later, in October 1415, Henry V led the English on another campaign in France. After capturing Harfleur and proceeding towards Calais, dwindling supplies, poor weather and casualties weakened Henry’s army. Large numbers of French knights began to converge on Henry’s position, detecting the weakening condition of their foe. At Agincourt, the French army was four times the size of the English force and now blocked their path. Henry was forced to fight.

The French were supremely confident of defeating the English through their superior numbers, the weakened condition of the English and the superb quality of their knights. Their commander, who was not of noble birth, intended to send foot soldiers into battle first and then carry out a flanking manoeuvre with the knights to destroy the English archers. However, Henry assembled his army on ploughed land made muddy by recent rain and placed his archers in the narrowest part of the battlefield, where sharpened stakes were set in the ground with bowmen and men at arms arranged among them so they could crouch, “hedgehog-like”, upon an assault by the French. This manoeuvre prevented the French from outflanking the English archers, as either side of them was thick forest, and forced a frontal assault across muddy fields.

To intimidate the English archers, the French promised to cut both of their bow fingers off to prevent them from ever drawing a bow again. The English archers now taunted the French by waving those two fingers in the air. This show of defiance so enraged the French knights, vastly superior in number, that they charged across the muddy field without their commander’s approval. Hail after hail of English arrows followed and, as before, knights and horses were cut down. The huge numbers of knights also meant that those behind continued to press forward, preventing those in front from manoeuvring, crushing those that had fallen, and impaling others on the English stakes: “so great was the undisciplined violence and pressure [of the second French line] that the living fell on top of the dead”. In this carnage, the English men at arms then came forward to finish off the floundering French knights. The French losses were again immense, with an estimated 6,000 dead in the first 90 minutes of battle. In total, the English lost just 150 men.

Despite these huge defeats, French nobles continued to patronise the armourers of Europe for a further 130 years. The incremental changes to armour only rendered the knights slightly less vulnerable to arrows, while making them slower, less manoeuvrable and thus easier targets. Indeed, the French investment in armour continued well beyond the point when firearms made it totally obsolete.

2-3 Rover: Slipping or Skidding?

In the 1950s, the Rover Car Company was a highly successful small firm operating in a niche. After World War II, demand had been increasing steadily as disposable incomes and social expectations had risen. It was a time of post-war patriotism, and Rover’s conservatively styled cars, built in Britain, had wide appeal. Many cars were also exported.

Rover P4 saloons were conservatively styled and appealed to the professional classes, such as doctors and solicitors. The cars had sumptuous interiors with handmade leather seats and polished wood fascia. The company also led the way in technological developments, such as with the creation of a gas turbine car. Design innovations added to the firm’s reputation for quality, with its new models being perceived as cutting edge. The Rover 2000, launched in the 1960s, was a radical new design and a huge hit with customers.

While the car market continued to grow during the 1960s, Rover found itself unable to meet demand, quoting waiting times of up to three years. At the same time, there was a considerable rise in car imports from the continent so that, by the 1970s, one in seven cars sold in Britain was a continental car. The firm recognised the need for greater scale economies and invested in machinery to improve efficiency and reduce the need for, and costs of, skilled labour. To operate these machines, large numbers of unskilled workers were hired.

While technology was being widely adopted by major car manufacturers, at Rover, skilled workers argued that the machines didn’t really replace them. For instance, although a highly sophisticated and very expensive computer-controlled paint shop was installed, skilled workers argued that they were still needed to deal with parts of the paintwork not covered adequately by the automated process. Workers were also paid for each task they undertook. Every time a new machine was installed, wages had to be renegotiated.

At this time, trade union power in Rover, and across the UK, was very high. The unions in Rover were very militant and there was real suspicion that this militancy was encouraged by communists attempting to destabilise the capitalist system. The number of strikes reached epidemic proportions with as many as 100 per year. The strikes also seemed to be called over the most inconsequential of issues.

Top management recognised that Rover’s profits were not rising as quickly as the cost of developing new cars. The rising costs of new technology were a growing burden and R&D was increasingly expensive. Despite the introduction of greater automation, frequent strikes meant the company was still producing far too few cars. At this time, the view became established that Rover was too small to compete worldwide. The Government therefore backed a series of mergers between many of Britain’s car companies to form British Leyland (BL).

In 1973, oil prices surged upwards causing a slump in demand for new vehicles. This forced BL into the red. The Government took the view that the UK car industry, predominantly BL, had to be preserved. In 1975, the Government took a stake in its ownership and poured £1.4bn into the company. The most modern car factory in Europe was built to produce 3,000 cars per week, but only managed 1,500 because of outdated working practices. At this time, BL was losing £1m per day. At the same time, cars imported from Japan were finding ready buyers in the UK market, where reliability was valued.

To stem the bleeding, Sir Michael Edwardes was appointed to turn BL around. His recommendation was to reduce the size of the company and to get rid of the union activists, Red Robbo (the factory union leader) in particular. Although he knew this would meet with fierce union resistance, Sir Michael believed that the workers were fed up with incessant strikes. He decided to go around the unions and ballot the workers directly about the need for mass redundancies. Although close, Sir Michael won. Red Robbo departed, mass redundancies took place and union power was reduced substantially. However, despite the cuts, BL still had insufficient funds to invest to produce cars of a similar quality to the Japanese imports.

To address Rover’s main weaknesses of poor mass production, poor technology and a lack of capital for investment, an alliance was formed with Honda. From Honda’s perspective, Rover offered good distribution and a design competence for the UK and European markets. The first joint product was the Rover 800, which turned out to be the most successful car since the 1960s. It had Rover styling but contained Honda engines and gearboxes. At the same time, however, there were mass resignations of Rover’s engineers who felt that they were now being overlooked. Rover’s engineering centre was subsequently put up for sale.

Now that BL had regained profitability, the UK Government tried to sell the company, but there were no offers from other car companies. Eventually British Aerospace bought the firm, although it was widely suspected that this was a political deal and not one focused on developing BL for the future. Shortly afterwards, Rover was purchased by BMW who invested huge sums in new product development and the introduction of German practices. Honda immediately withdrew from the alliance and viewed the sale as a breach of trust.

While BMW poured billions into creating new car designs to complement its own range, such as the Land Rover Defender, a new Mini and new 45 and 75 models, it encountered huge problems at the massive manufacturing facility at Longbridge. Despite sending in hundreds of BMW engineers from Germany, the problems remained. There were also intractable difficulties in dealing with the myriad suppliers who resisted change. BMW’s losses were so significant that the parent company was being harmed by “the English Patient” and made strategically vulnerable to takeover itself. There were rumours that Ford was even in talks with BMW’s owners. Facing sustained losses of £500m per year, BMW sold Rover to a management buyout team, although they kept the Mini and 4x4 production lines. In 2005, Nanjing Automobile, who then moved production to China, acquired the assets of the company. SAIC also acquired some Rover technology that then featured in a new line of luxury cars. SAIC and Nanjing Automobile merged in 2007. The Rover marque had been acquired by Ford and was subsequently sold to Tata in 2008.

2-4 Nike: Learning and Doping

Nike was founded in 1964 when Phil Knight put an MBA project he’d written into practice with Bill Bowerman, his former track coach at the University of Oregon. At a time when established companies were manufacturing sports shoes in high-wage economies, Knight’s project had shown that decreasing transport costs would mean that higher margins could be gained by sourcing shoes from countries with low labour costs. Nike began by importing shoes from Japan. However, one morning Bowerman was standing in his kitchen and had an idea. He made an outsole by pouring a rubber compound into a waffle iron. The waffle trainer was born and Nike became a design company rather than just an importer.

Initially, Nike outsourced almost all of its production to plants in Japan. However, in the early 1970s, as costs there began to rise, it was switched to Taiwan and Korea. By 1982, only Nike’s headquarters and design facility (or “campus” as it is called) were located in the USA. In 1999, Nike employed 13,000 people in the USA, while its 350 subcontractors employed nearly 500,000 in plants in China, Vietnam and Indonesia.

Knight and Bowerman’s personalities fired Nike’s purpose: a love of athletics, an appreciation of the views of real athletes and a relentless appetite for competition and striving for number 1. “Every time I tour people around [the Nike ‘campus’],” explains Geoff Hollister, who ran track with Knight at college, “I show them a picture of Phil Knight running behind Jim Grelle. Grelle was a champion and Knight never caught him – but he never stopped pursuing.”

Knight’s passion for athletic excellence attracted young and confident employees with a similar outlook. According to Nelson Farris, another of Knight’s former track teammates: “We like employees who aren’t afraid to tee it up.” The campus culture was subsequently pervaded with an “athletistocracy” that placed athletic achievement through innovative design above everything else. An article in The Sunday Times recently claimed that the words “I work for Nike” seem to have the same appeal as “I work for NASA” did 30 years ago. Those on the Nike campus developed a particular pride in their work. Once part of the fraternity, they are famously devotional. Many have tattoos of Nike’s trademark “swoosh” on their bodies.

Nike’s values are powerfully expressed in their marketing. The swoosh – which ranks alongside McDonald’s golden arches and Coca-Cola’s red and white logo as being recognised by 97% of Americans – speaks of a no-nonsense emphasis on speed and performance. The Nike tag-line “Just Do It” (born in 1988 when an advertising executive told Nike staff: “You Nike guys, you just do it”) is the second most recognisable slogan in the USA after the Marlboro Man.

In the words of one commentator, this devotion and recognition enabled Nike to “instill its products with a kind of holy superiority”. And this “holiness” and the continued growth that ensued saw Nike go from strength to strength. Its share price rose 3,686% in the period from 1980 to 1997. Nike overtook Reebok to become market leader in sports shoes in 1988. In the three years to 1996, Nike more than doubled sales, moving from a 32% share of the market in 1994 to 45% in 1996. In the three years to 1997, the group tripled in size, with worldwide sales up to $9 billion and profits to $800 million.

After achieving number one status in sports footwear, Nike pursued an increasing number of new initiatives. In 1992, Knight claimed that he wanted Nike to be not just the world’s best athletic shoemaker but “the world’s best sports and fitness company”. In an interview in the Harvard Business Review that same year, Knight described a further transformation in Nike. “For years we thought of ourselves as a production-oriented company, meaning we put all our emphasis on designing and manufacturing the product. But we understand now that the most important thing we do is market the product. We’ve come around to saying that Nike is a marketing-oriented company.” The new emphasis on marketing saw Nike seek to exploit and ram home the rebel image, with “Just Do It” supported with slogans like “You don’t win second you lose first”.

Nike moved into further pastures – including “redefining retailing” – with the launch of Nike Town stores (described as being “more like theme parks than shops”), and becoming more fashion conscious in its product design. The initial response from journalists, at publications like Vogue at least, was positive. Moreover, Nike set out to “redefine and expand the world of sports entertainment” with a joint venture with a Hollywood talent agency. The aim here was to package up events in which Nike endorsers like Charles Barkley and Michael Jordan were involved and then sell this on to sponsors and media companies. Nike’s director of advertising outlined the potential: “Forget the business Nike’s in at the moment. This is going to boom across the map, and massive amounts of money can be made.” By 1996, Nike was increasingly slapping its swoosh on everything from sunglasses to footballs to batting gloves and hockey sticks, with Nike’s VP of corporate communications proclaiming: “We are not a shoe company.” Phil Knight’s stated objective for Nike in 1996’s annual report was the “‘Swooshification’ of the world”.

However, 1997 saw a decline in Nike’s fortunes. Analysts predicted that Nike’s share of the world athletic market would drop from 47% in 1997 to 40%; correspondingly, profits had fallen by 69% at the end of 1997. The share price, which stood at $72 at the beginning of 1994, hit $30 in August 1998. Standard & Poor’s subsequently downgraded its outlook on Nike from “stable” to “negative”. The normally gung-ho Knight admitted to Advertising Age in 1998: “Everything we have tried over the past six months simply has not worked.” What happened?

In the ever-fickle fashion stakes, even Nike’s own people admitted that “we’re just not cool anymore”. Marketing guru Peter York claims that “Nike [knows that they are] not what matters at the moment,” and that this recognition has led to there being “… an air of desperation about them now. They’re doing too many special runs and limited editions, trying too hard to keep their cool. They’ve had brilliant brand marketing, but their brand stretches are unproven.”

Even more problematic, however, were the protest groups and media investigations focusing on alleged abuses at Nike’s foreign factories. The allegations made included employing children sold to the factories by brokers; poor air quality caused by petroleum-based solvents leading to breathing problems in some factories; paying well under the minimum wage; and the lack of sick pay and compensation, even for industrial injuries. Internet sites with names like www.boycottnike and www.nike-sucks fuelled the anti-Nike feeling that these allegations generated.

While Nike was actually doing little that was different from other sportswear companies, Medea Benjamin, director of Global Watch, admitted that Nike was targeted because it was “the biggest and it sets the trends. I wish we had the resources to look at Reebok, Adidas, and Converse, but we don’t.” Indeed, it was not just that Nike had become the biggest; it had also become the loudest. As Thomas Bivins, Professor of Public Relations at the University of Oregon, argued: “When a company goes out of its way to create an image [like Nike’s], it is going to be a big target.”

Nike responded as if they were mounting a legal defence. They sought to distance themselves from the factories, claiming that what their contractors did was none of their business. After this failed to wash, Nike’s PR spokesperson declared: “In a country where the population is increasing by 2.5 million a year, with 40% unemployment, it is better to work in a shoe factory than not have a job.” But the public response just got worse.