11

Evaluating Strategic Performance

What gets measured gets managed [but some of the most important issues in strategic management cannot be quantified at all].

Peter Drucker

Jimmy Choo makes great shoes. A Malaysian fashion designer, Jimmy Choo’s business attracted global attention when his shoes were worn by Princess Diana, and then were made famous by the US TV series “Sex and the City”.

But just three years after listing on the UK stock market, the business has been put up for sale. Its owner, JAB Holdings, the investment vehicle of the German Reimann family, are unwinding their positions in high-end goods and focusing upon lower-value consumer products.

At the time of writing, Jimmy Choo’s reported profits are £59m, its shares are trading at 204 pence and at a PE of 49x. There is speculation that Coach, the US handbag giant, has enough cash to offer £1bn for the company. These look like big numbers and on the face of it Jimmy Choo, the company, seems successful. But any potential acquirer needs to fully evaluate Jimmy Choo’s stand-alone strategic performance before it considers what it might bring to the business as a new parent. And Jimmy Choo’s current managers need to be mindful of the damage that a new parent could do to the family brand.

So, how has Jimmy Choo performed to date? How should its strategic performance be evaluated? What are its prospects for the future? Our first Pathway chapter set out the importance of having a clear over-arching strategic purpose that reflects an organisation’s identity (Jimmy Choo’s is certainly clear about that: “Jimmy Choo is a 21st century luxury accessories brand, with shoes at its heart, offering an empowered sense of glamour and a playfully daring spirit” jimmychoo.com/en/customer-service/about-us.html). But our penultimate chapter now investigates how performance toward that purpose – how an organisation has fared so far, its ability to win and keep winning – can be evaluated and managed.

We do this by starting with a review of traditional or conventional stock market and accounting-based performance measures, then we look at assessing performance more strategically. After this, we investigate the growing awareness of ethical principles that should be adhered to, and environmental and social measures of success. We conclude by offering some suggestions as to how this broad range of concerns can be balanced, and the risks associated with them mitigated. But first, back to Jimmy Choo …

Accounting-Based Performance Measures

The classic way to begin evaluating the strategic performance of an organisation is to reach for the financials to evaluate the company’s health. This is historical analysis and uses accounting measures of performance. An organisation’s annual report and accounts is the best source for this information if available (see www.companieshouse.gov.uk for instance, although there are many other sources of data, such as www.bloomberg.com; www.financials.morningstar.com; www.thomsonreuters.com etc.).

Key questions to ask include whether sales are growing or in decline. Is the organisation’s market (or segment) share increasing or in decline? What costs are being incurred to make those sales – and is this changing over time? Overall is the organisation profitable and how does this compare with previous years? For Jimmy Choo, the annual report shows that the organisation has sales of £364m (2016), most from retail, and 76% of this is from the sale of shoes. Sales increased 6% from 2014 to 2015 and 14% by end of 2016, which appears healthy. The company achieved a consolidated net income of £19.4m, whereas the previous year it made a £10.8m loss partly due to the costs of listing on the stock exchange.

Apart from raw data that is published in an organisation’s accounts, performance ratios can reveal deeper insights into how an organisation is doing. For instance, what is the Return on Capital Employed (ROCE: profit before interest and tax divided by capital employed)? This indicates the organisation’s effectiveness in generating profit from assets. ROCE can be broken down into its constituent parts, using DuPont analysis (see www.investopedia.com/articles/fundamental-analysis, for instance), that will allow the analyst to understand the constituents of sale margin and capital productivity and the specific activities that are sources of superior (and inferior) performance. Other measures of profitability to consider include Return on Equity (RoE) (Net Income divided by Shareholders’ Equity), Return on Assets (RoA) (Operating Profit divided by Total Assets), Gross Margin (Sales minus Cost of Goods and Services divided by Sales), Operating Margin (Operating Profit divided by Sales) and Net Margin (Net Income divided by Sales). This is not an exhaustive list of profitability ratios that can be calculated, but they are generally the most widely used. Jimmy Choo’s operating margin is 9.4%.

One should also be mindful of how an organisation is being funded in order to achieve its performance. For instance, does it have high levels of debt (gearing or leverage)? Jimmy Choo has net debt of £121m. What is the cost of capital? Typically, an organisation’s cost of capital consists of the cost of equity capital (required dividend and capital gain) and its cost of debt capital (interest rate). When compared with operating profit after tax, an organisation’s Economic Value Added (EVA) can be calculated (EVA = net operating profit after tax – cost of capital). The big advantage of using EVA is that it takes risk into account as the higher the risk, the higher the interest rate on debt and shareholder dividend expectations.

In order to interpret the ratios listed above, comparisons are required, both over time and against competitors. For instance, comparisons over time will tell you whether a profitability measure is improving or deteriorating. Jimmy Choo operates in the luxury consumer goods industry, dominated by LVMH, which is capitalised at £126bn. Other competitors include Christian Dior (£50bn), Coach (£12bn) and Burberry Group (£9bn). They have much more robust net income figures (LVMH: £4bn; Christian Dior: £1.6bn; Coach: £511m; Burberry Group: £262m) and much stronger operating margins (LVMH: 18%; Christian Dior: 17%; Coach: 23%; Burberry Group: 17%). Jimmy Choo is clearly a small company in comparison to these competitors which might mean there are economies of scale in the business and/or that Jimmy Choo is not as well run as the other companies.

Stock Market Performance Measures

An organisation’s share price reflects its earnings and dividend payments, both historic and future. In this way, it contains fundamental value as well as future expectations. An organisation’s share price means little in isolation but being viewed over time, and in comparison with competitors and indexes, it can be very revealing. In the case of Jimmy Choo, the share price has jumped in the last nine months and this needs explaining. It could be that the luxury goods industry is improving (rather than anything Jimmy Choo is doing) and it might also be due to some anticipation that the business might be sold. Compared with the sector, since going public Jimmy Choo’s share price has underperformed the luxury goods sector, although the recent surge has brought it much closer to the norm.

An organisation’s P/E ratio is the ratio of the organisation’s share price to its earnings per share (P/E = share price divided by eps). It denotes a market’s expectations of an organisation’s risk or growth or both, so that a low P/E ratio suggests low risk or low growth, or both, and visa versa. As with an organisation’s share price, its P/E needs to be compared with other competitors, its sector/industry and even the market as a whole in order to be able to interpret effectively. In Jimmy Choo’s case, its P/E of 49 is substantially higher than top competitors such as LVMH (29x), Christian Dior (29x); Coach (23x); Burberry Group (27x) and the luxury goods sector of 18.3x. This might reflect very high growth expectations of Jimmy Choo, plus takeover prospects for the company, but might also reflect very high risk. To get answers to this question, and to understand the numbers in more detail, it is necessary to carry out a strategic assessment.

Strategy Assessment

The brief review above indicates a number of performance measures that ought to be taken into account when embarking on a review of an organisation’s performance. The treatment here is only to highlight a few indicators and does not represent a comprehensive review of what would normally be conducted, nor the detail of the techniques that should be followed, for which there is insufficient space here. However, these key figures and comparisons will raise important issues to consider, not least around the strategic purpose of an organisation and, importantly, how achievable this will be in the future. For instance, even if an organisation is exhibiting high profitability today, based on a specific competitive advantage, to what extent is this likely to continue? This requires a detailed understanding of how the business is competing in its market(s) (Chapter 4), what supports the organisation’s competitive strategy (Chapter 5) and the nature of its business model (Chapter 6). For Jimmy Choo, for instance, the company clearly produces a highly differentiated product with a premium price. Originally its success was based upon the talents of Jimmy Choo himself and co-founder Tamara Mellon. Choo left the company in 2001 and Mellon left in 2011. In 2016 she launched a lawsuit against the firm, saying it had bankrupted the new business she started. In organisations of this type there may well be follow-on talent able to design for this company in an effective way, and there will be momentum to their sales from previous success, but new designs that are distinctive and appeal to its target customers are critical to the future success of Jimmy Choo. Reviewing the backgrounds of the Board of Directors may reveal the extent to which there is design talent in evidence, as this is key to Jimmy Choo’s success. The attractiveness of Jimmy Choo to an acquirer such as Coach should be whether there is a unique shoe design capability that sustains the company’s competitive advantage. Although Coach may be a better-run company and could probably make Jimmy Choo more efficient through economies of scale, and so achieve a short-term financial gain through streamlining the business, for the purchase to have long-term value, the sources of competitive advantage must be in place, and remain post deal.

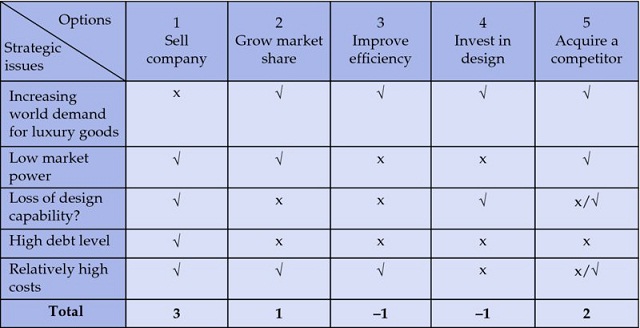

So far, we have only considered Jimmy Choo from the perspective of a potential buyer. It is also important to think of its strategic position from the perspective of its own top management (and the owners). Why is the business for sale? Is it just that the owner has other agendas to pursue or do they feel that Jimmy Choo will not be a good investment in the future. To better understand this viewpoint, it is useful to review the strategic options open to an organisation. One way to do this is to create a strategic options grid to evaluate the best way forward for Jimmy Choo (see Figure 11.1). Strategic issues that are relevant to the organisation will have been identified through earlier analyses (using Chapters 1–10 in the Strategy Pathfinder). Strategic options may be self-evident, but also can come from creative insight.

Figure 11.1 Strategic option grid for Jimmy Choo

Note:The totals are the sum of the ticks (positives) minus the ‘x’s

Figure 11.1 is just a simplified indicative analysis, but it would seem that selling the company (option 1) would solve the main strategic issues of Jimmy Choo being a very small competitor with high costs in an industry where scale seems to matter, diminished design capability and a relatively high debt level. However, selling the organisation would mean it would miss out on the growth possibilities presented by the current rise in global demand for luxury goods. Growing market share (option 2) or even making an acquisition (option 5) might be alternative ways forward, although the company may not have sufficient resources to do either of these on a big enough scale to make a difference, and they may not get backing from their shareholders. The analysis could therefore be refined by weighting the relative importance of the strategic issues, which may help decisions and also by creating new options as hybrids of the original ones. Additional information could also be added to the grid, including the amount of time that each option might take to work out and additional resourcing implications. On the face of it, it would seem to be clear why the owners, the Reimann family, may wish to sell Jimmy Choo, but it is less clear why another company may want to buy it.

Broader Views of Performance: Ethics and Sustainability

While our discussion about Jimmy Choo so far has highlighted the importance of a sustainable strategy, this has been about focusing on whether the organisation’s competitive advantage may be sustainable going forwards. This is a narrow definition of sustainability that can ignore important aspects of an organisation which could undermine its future. A classic example in the UK was a speech by Gerard Ratner, former chief executive of a major UK jewellery business, Ratner Group. At a conference at the Institute of Directors he was asked how he could sell his jewellery products for such low prices? His response was: “because it’s total crap”.1The stock market reacted badly to the speech and the value of the Ratner Group fell by around £500 million, nearly resulting in the organisation’s collapse. “Doing a Ratner” is evidence of the power of CEO communications to make a difference to share prices, although in this case it also severely damaged the reputation of the company. However, it also raises ethical issues about whether it is right and proper to knowingly sell poor goods at inflated prices, even if it is not illegal. Ethical performance has become increasingly important in evaluating organisational performance – and for good reason …

The first decades of the 21st century have not been good for the public image of business. On 29 June 2009, Bernie Madoff was sentenced to 150 years in prison for defrauding investors of over $65bn through the mechanism of a giant Ponzi scheme (i.e. a scheme that promises high returns but uses the investment funds of subscribers to pay other subscribers). Mr Madoff was no fly-by-night conman. His investment company had started in the 1980s and he had risen to become a highly respected member of the investment community with positions on several prestigious non-profit boards as well as serving as Chairman of NASDAQ. He was a trusted pillar of the business community. He turned out to be a crook.

Such individual examples aside, the early years of the 21st century have been dominated by the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). A combination of factors including the overuse of debt to leverage returns, the assumption that bundling and splitting risk somehow removed it, and the underpricing of risk in general, etc. led to a big bang and the collapse of financial institutions and other companies around the world. Huge bailouts by governments were necessary to keep large institutions afloat and prevent an even more catastrophic outcome. There is a strong sense among many that the causes of the crisis emanated from the greedy, cavalier managers who, while quick to demand the rewards in good times, were equally quick to demand that society, in the form of government, throw them a lifeline when all their bets were losing ones. If you like, “private gain – public pain”.

Mr Madoff’s breach of trust and the sharp practices that contributed to the GFC are sadly not the only issues that have lowered people’s view of the role of corporations and their leaders in recent years. Consider, for example:

- The high-level chicanery at firms like Enron and World.com, aided and abetted by auditors with equally questionable values.

- The exploitation of gullible investors by “entrepreneurs”, analysts and financial services companies, with vested interests.

- The egregious level of financial compensation conferred on senior executives while they are in the job and when they are sacked, for instance Royal Bank of Scotland CEO, Fred Goodwin.

- The cavalier attitude to consumer health demonstrated by various companies as they orchestrated silence and deception about the effects of their products.

- The blind eye turned to the exploitation of off-shore workers, including children, by some of the most famous branded goods companies in the world.

- The connivance with corrupt officials and governments by some extraction companies keen to protect valuable leases and mining rights.

- Popular movies and books, such as The Corporation or Michael Moore’s works, which have presented these sorts of infamy to an increasingly receptive audience.

- The sub-plots of popular movies from Wall Street to Avatar to The Lego Movie (whose villain is the evil “Lord Business”) that “big business” is sinister and an exploiter of innocence and environments.

- BP’s pollution of the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 and its seemingly lacklustre response

- VW’s diesel emissions scandal (“dieselgate”).

These, and many other examples, raise expectations and pose questions about the scope of our evaluation of organisations. In particular, shouldn’t we expect organisations to act ethically? And shouldn’t organisations be interested in social and environmental goals rather than just short-term financial measures of success.

Business Ethics and Corporate Integrity

The developments outlined above have ignited debates about business ethics by making it increasingly untenable for organisations to simply stand behind Milton Friedman’s famous claim that a company’s responsibility is only to conduct “business in accordance with [shareholders’] desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society”. They must be mindful of their corporate reputation and integrity.

While it is impossible to do justice to the burgeoning field of business ethics here, we offer some simple ideas that can help strategists think about their ethical performance.

Two ethical orientations

Since at least the time of the Ancient Greeks there have been two different ethical strands of thought.

The first is often termed a deontic approach (deos meaning “duty” in Ancient Greek, and, more commonly now in modern Greek “fear”). This is an “outside-in” approach based on aspiring to universal Platonic ideals. For organisations, this kind of ethics is generally manifest in written codes outlining acceptable conduct, standards, responsibilities and corporate duties which can be referred to when ethical questions arise. A famous example is Johnson & Johnson’s “Credo”, which you may like to Google.

The second is an approach often traced back to Aristotle, where ethics is related to individual and particular virtues which can be discerned “inside-out”, from self-reflection on one’s particular role within a community. This approach is often termed aretaic (arête meaning “virtue”) and in organisational terms is closely related to the open and honest portrayal of the organisation’s corporate identity that the company will adhere to. So, for example, a low-cost airline that markets low price as their primary virtue cannot be accused of being “unethical” if they only adhere to minimum industry standards in other respects: they are being consistent with their well-publicised virtue of being “low-cost”. In modern times, we might regard an aretaic approach more like an “ethos” than ethics.

Three ethical principles

- “Do not do to others what would anger you if done to you by others.” This quotation is from Isocrates, but it is a sentiment that dates back to ancient Babylonian texts and is captured in the often expressed aphorism: “Do unto others …”. From an organisational point of view this might be applied by asking questions such as “Do we treat our staff (or customers etc.) as we would like to be treated”?

- “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become universal law.” This is Immanuel Kant’s famous “categorical imperative”. In an organisational setting, this might encourage reflections such as: “I could cut corners with this trade, but what would be the result if this ‘cutting corners’ became the norm?”

- “The moral worth of an action is determined by its utility in providing happiness or pleasure as summed among all beings.” This is the founding principle of Utilitarianism of whom Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill are the most famous proponents. It is often described using the phrase “the greatest good for the greatest number of people”. In an organisation, one might reflect on how much good a particular decision might bring to stakeholders, relative to another potential course of action.

Whether one favours a deontic or aretaic perspective, or both; whether you feel more attuned to the categorical imperative, utilitarianism or another ethical principle, the aim should be fidelity and reflection. Fidelity to the chosen orientation and the principles and statements that emanate from them; and, at the same time a willingness to reflect upon and respond to changes in social, ethical, legal and ecological beliefs in the wider environment (the S E L E of ESTEMPLE outlined in Chapter 2).

While the term integrity has been increasingly bandied about in business circles, it has been used loosely and without a clear sense of what it really entails (Enron listed integrity as one of its core values). Strategists would do well to give clearer meaning to integrity by understanding it in these ethical terms.

Sustainability and The Triple Bottom Line

Students and practitioners of strategy are familiar with the concept of sustainability in the context of a sustainable competitive advantage. Advantage is sustainable if the underpinning sources are not substitutable or imitable. The durability of any advantage is a function of the isolating mechanisms impeding copying (see Chapter 4 Competitive Advantage). However, the concept of sustainability has taken on broader connotations since the World Commission on Economic Development (WCED) drew attention to the need for sustainable development as “… development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”.2

This rather loose definition has likely contributed to much of the rhetoric about sustainability lacking clarity, with sustainability becoming a rather amorphous catch-all term used to incorporate everything from corporate social responsibility to only using renewable resources and organic farming, resulting in arguments with cross-purposes. Hence, while we believe that strategists must take the force of feeling behind sustainability seriously, they would also do well to be clear about what aspect of the phenomena they are actually implying in their arguments. Table 11.1 presents a range of related concerns that can be grouped under the “sustainability” banner.

Table 11.1 Ecological concerns related to sustainability

| Biodegradable | A product that will decompose into the earth without having a negative effect on the environment. |

| Carbon footprint | The amount of greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere by manufacture, transport, materials, activities, etc. |

| Carbon neutral | Human activities that do not increase the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere, or if they do are offset by activities that reduce CO2. |

| Ecological footprint | The amount of land needed by a person or population to sustain their lives with the consumption of natural resources, calculated and compared to the earth's ability to generate these resources. |

| Energy efficiency | Achieving the same outcome with less energy, such as achieving the same light from a lower wattage light bulb. |

| Organic | An alternative farming method that removes toxins, manufactured chemicals, synthetic additives, genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and provides products which are biodegradable. |

| Waste neutral | When the weight in kilos/pounds for products that are to be recycled is the same amount as the weight of products to be made from the recycled products. |

| Recyclable | A product or packaging that can be recycled when the end of its life cycle has been reached (e.g. cans that can be broken down into their pure matter and made into new cans). |

| Renewable materials or energy technology | Natural raw materials (e.g. timber) that can be replenished over time or using natural and perpetual energy resources such as water, wind and sun. |

| Remanufacturable | When a product reaches the end of its life cycle, it can be manufactured for a second time using the parts which remain functional (e.g. refillable printer cartridges). |

| Repurposable | A product or material which is used for another purpose once its original purpose has completed (e.g. packages such as glass jars which can be used for home storage). |

| Reusable | A product or material which is used again and again for the same purpose, such as milk bottles. |

In response to the convergence outlined above, businesses are demonstrating a commitment to sustainable development (or at least its language and reports) through reporting on the so-called triple bottom line (TBL) of economic, social and environmental performance. Economic reporting relates to the traditional balance measure of financial performance. Environmental performance relates to the sorts of concerns listed in Table 11.1. And social performance tends to be used to report upon employee and community well-being (see Table 11.2 for an example of the sort of things that might be thought through and inputted into a TBL analysis of a particular activity).

Table 11.2A “worked example” of TBL thinking from Longmount (Colorado) City Council

Street sweeping Economic factors:

|

|

Environmental factors:

|

Social factors:

|

Source: www.ci.longmont.co.us/city_council/agendas/2010/documents/033010_4C.pdf

In 1981, Freer Spreckley first proposed that organisations could report on social and environmental performance, in addition to the measure of revenue less costs traditionally shown on the bottom line of a financial statement, in a work called Social Audit – A Management Tool for Co-operative Working. In 1995, John Elkington developed a phrase reflective of these three bottom lines: “people, planet, profit”. This was adopted as the title of Shell’s first “sustainability report” in 1997. However, the phrase “triple bottom line”, which came to name the approach, was first coined by John Elkington in the 1997 book Cannibals with Forks.

Triple bottom line reporting became the dominant approach in public sector full cost accounting in 2007 following its endorsement by the UN. And most financial institutions now incorporate a TBL approach, and in the private sector a commitment to corporate social responsibility or sustainability now implies a commitment to some form of TBL reporting.

A lack of clarity around how the social and environmental bottom lines might be balanced, measured or related to the financial bottom line of an organisation means that often the social and environmental sections of TBL reporting are simply lists of intentions or commitments, targets and achievements. However, reporting and publicising commitments and achievements with regard to the three bottom lines is becoming commonplace, with laggards under more scrutiny to explain their lack of transparency. To some companies, TBL is no more than dealing with one of the “pests” of PEST, or ESTEMPLE, but to others it is regarded as a strategic necessity, not only in terms of diffusing potentially hostile political and social forces, but also in terms of potential reputational disadvantage in the minds of environmentally sensitised customers. Indeed, quotes such as the following by Bill Ford in 2005 are a good example of how these three bottom lines have become a part of today’s strategic language: “My great-grandfather’s vision was to provide affordable transport for the world. I want to expand that vision for the 21st century and provide transportation that is affordable in every sense of the word – socially and environmentally, as well as economically.”

While there is growing awareness of TBL, some commentators, notably Jeffery Pfeffer, have noted that the intense debate around ecological sustainability may have diverted attention away from human and social sustainability, particularly with regard to employees.3 However, new league tables focusing on employee engagement and “best places to work” should ensure that this does not get lost in the wash. Indeed, one thing is certain: at a time when organisations are increasingly concerned with how their corporate reputation can positively or negatively impact on their likelihood of survival, there are an increasing number of ways that performance and reputation are being measured beyond the traditional singular emphasis on financial performance (see Table 11.3).

Table 11.3 Alternative measures of performance that are linked to economic, social and environmental reputation (all information from Fortune.com)

| 2017 performance ratings | “Fortune 500”: America's biggest companies by annual revenue | “Fortune 100 Best Companies to Work For” (based on employee surveys) | “Fortune World's Most Admired Companies” (based on surveys of people external to each company) |

| 1. | Walmart | Apple | |

| 2. | Exxon Mobil | Wegman Food Markets | Amazon.com |

| 3. | Apple | Boston Consulting Group | Starbucks |

| 4. | Berkshire Hathaway | Baird | Berkshire Hathaway |

| 5. | McKesson | Edward Jones | Disney |

| 6. | United Health Group | Genentech | Alphabet |

| 7. | CVS Health | Ultimate Software | General Electric |

| 8. | General Motors | Salesforce | Southwest Airlines |

| 9. | Ford Motor | Acuity | |

| 10. | AT&T | Quicken Loans | Microsoft |

Balance in All Things: The Balanced Scorecard and Risk Assessment Matrix

As we come to the end of our penultimate pathway, it is clear that strategy, like life itself, is about balancing competing demands and opportunities, benefits and risks in order to win – or achieve an overarching purpose. Just as people must balance acknowledging past relationships, enjoying the present and planning for future well-being, organisations too must achieve a similar balance in determining their strategies.

The Balanced Scorecard

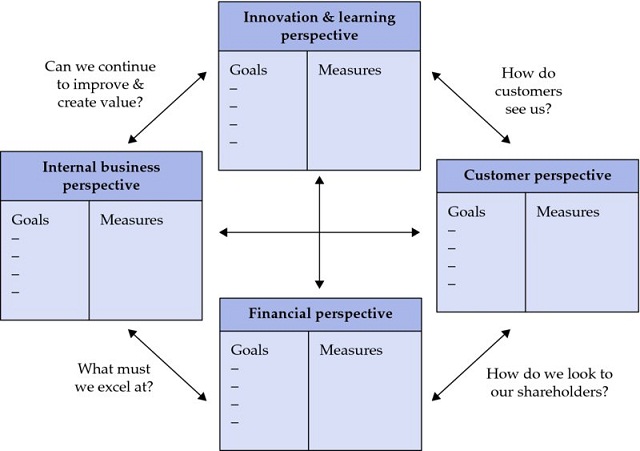

The most popular framework for helping managers to think strategically about how to balance internal and external demands and short-term and long-term goals is Kaplan and Norton’s Balanced Scorecard approach.4 This encourages the use of multiple criteria beyond the traditional financial measures that are generally used to assess performance, enabling us to factor ethical, environmental and social concerns into discussions about managing strategic performance.

The term Balanced Scorecard was developed by Art Schneiderman in 1987. Schneiderman participated in an unrelated research study in 1990 led by Robert Kaplan for management consultancy Nolan-Norton, and during this he outlined his work on performance measurement. Kaplan and David Norton subsequently developed the idea and published a 1992 Harvard Business Review article, “The balanced scorecard – measures that drive performance”. The article proved popular and was quickly followed by another in 1993 (“Putting the balanced scorecard to work”) and a book, The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action, in 1996.

The aim of the Balanced Scorecard is the presentation of financial and non-financial measures so that their individual and collective value to the firm can easily be seen on a page or in a single report (see Figure 11.2). To create a simple cross or diamond shape for the framework, three categories are used in addition to a short-term financial perspective:

- how the customer views, and what they expect from, the organisation

- internal business perspectives and processes that deliver a particular type of product/s and service/s – whether that be “Jimmy Choo type shoes” for Jimmy Choo or “efficient air travel” for Southwest Airlines

- how the firm learns, innovates and protects itself and its environment for the long term (maybe the future problem for Jimmy Choo?).

Figure 11.2 The Balanced Scorecard framework

(Source: adapted from Kaplan and Norton, 1992)

By using a Balanced Scorecard, organisations can, on the horizontal axis, consider and match assessments: “What is our differentiated corporate identity?” or “How do our customers see us?” with “How do we meet, exceed or change these expectations?” or “What must we excel at?” While on the vertical axis, assessments about balancing the short-term financial goals that must be met for the organisation to remain viable can be balanced with the investments that must be made (in people, innovation, the environment etc.) to ensure a positive long-term future.

Finally, designing a Balanced Scorecard generally includes the identification of a small number of goals in each of these four areas and measures against which progress can be charted. The measures used for assessing Balanced Scorecard achievements on each of these four dimensions can be metrics, such as return on capital employed or return on net assets, or such factors as employee attitudes, extent of customer awareness and satisfaction, or the development of knowledge or skills within the organisation that can help to drive innovation and new product development.

The Balanced Scorecard approach is now very much a part of the strategic management landscape. It is regarded as best practice in the public sectors of many Western countries, and it is used in many for-profit and not-for-profit organisations to set the performance goals that reflect their purpose, toward which a firm’s strategy aims.

Risk Assessment Matrix

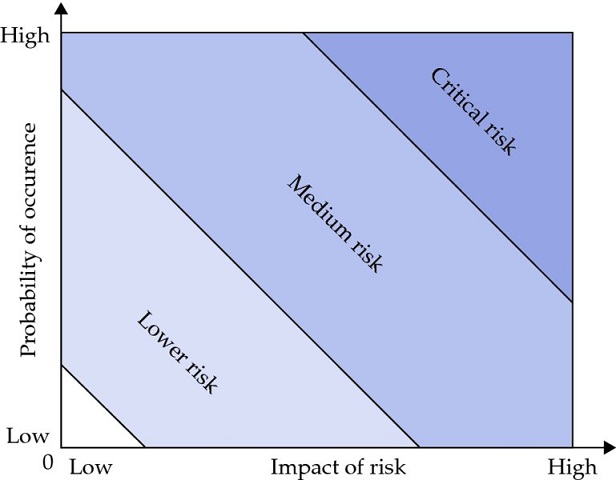

Risk management has a long history in both the finance and strategy literatures. In a nutshell, risk management is about the distribution of future outcomes as a result of internal decisions and the actions of external factors. The probability/impact Risk Management Matrix, shown in Figure 11.3, helps the user identify and analyse the different levels of risk that can be attributed to different initiatives, in the best interests of overall organisational purpose outlined here in Chapter 1.

Figure 11.3 A Risk Management Matrix

(Source: from Cummings and Angwin, 2015)

“Probability of occurrence” on the vertical axis is in reality a continuous scale, but it can be categorised as high/medium/low and attributed numeric values for the purpose of a general strategic, or big picture, discussion. “Impact of risk” is also a continuous scale but can be attributed categories in the same way. This means that you can adapt this basic figure which could be a grid with numeric scores attached or a conceptual space as presented above. Locating risks on the matrix allows a judgement to be made about what is the acceptable level of overall risk when one considers the various strategic projects the organisation has on the go or is considering, and the relationships between these.

For example, the case on Harley-Davidson at the end of this chapter puts you in the shoes of the managers of that company. They have decided to push ahead with a new electric bike – something that customers would never expected of them, and something that could be potentially damaging to the Harley brand – especially if they don’t do it well. But they have to balance a new initiative like this with the gradually rising probability that the market for their traditional big motorbikes is declining and that the impact of that could be critical to the brand over the longer term. How do they mitigate that risk?

The key message, with the Risk Management Matrix, and risk management in general, is not that risks and bold goals (be they economic, social or environmental) should be avoided or even reduced, but that people should be aware of them – they should be seen for what they are, and managed accordingly.

We have covered a lot of territory in this chapter: from valuing Jimmy Choo with traditional financial measures of performance and strategic options, to ethical considerations, sustainability concerns and the triple bottom line, and then how the Balanced Scorecard can be a way of encouraging a wide and balanced range of performance measures. This broad territory is testament to the fact that organisations have a far larger range of measures to consider when evaluating their strategic performance than is generally used. While many may argue about whether organisations are taking ethical, social and environmental concerns seriously, rather than just paying them lip-service in order to meet financial goals, there is now one point about which there can be no debate. The days of businesses claiming not to care, or not engaging with these issues, are gone. At the very least, the wider community, through the power of social media, for instance, will expect that all organisations consider, develop and defend a view of where they stand with regard to environmental sustainability and social impacts. Previously seen as the two poles of a performance axis to choose between – sustainable development or profitability – this is now a false choice as they increasingly become two sides of the same coin. As the words of Peter Drucker at the head of this chapter indicated, some of the most important things about an organisation’s strategy: environmental impacts, social factors, ethical stance, corporate reputation and sustainability, for example, are difficult to measure. But the more that citizens demand that they be measured and organisations seek to measure them, the more these aspects of performance will be managed.

Sustainability and profitability now co-exist – recognising and acting in accordance with this realisation is what will enable an organisation’s “sustain ability” into the future.

Strategic Evaluation Key Learnings Mind-Map

Having read and reviewed this chapter, outline what you believe to be the key learnings from the chapter and the relationships between these on the note pages below.

11-1 Southwest Airlines: Southwest Satisfaction

A survey by Airfarewatchdog in 2016 showed something that many considered unexpected. The air travel experts surveyed more than 11,000 customers and found that low-cost airline Southwest topped almost every category among domestic air travellers in the USA, and by a wide margin.

Southwest was rated best airline by 32% of those surveyed (the next highest airline was 19%); 47% of fliers gave Southwest top ranking, far in advance of any other rivals. But Southwest also earned top spot for its frequent flyer programme and service, while 45% of respondents thought that Southwest had the friendliest flight attendants, 31 percentage points ahead of the next best.

But anybody who has followed the results of these surveys will know that these results are not anomalies. Southwest consistently comes out on top in terms of customer satisfaction, and not just in the categories associated with the brand. How does a low-cost carrier outperform its rivals that provide more “frills” in categories like service?

The answer is focus.

Southwest prides itself on knowing what its customers value and want from them most: low-cost tickets, on-time departures and arrivals and travel made easy.

To match this, they focus primarily on standardisation and fast turnarounds so that planes have the shortest “on the ground” times of any in the industry. They do not take out frills just to cut costs, but to make their operations simpler and more efficient – this means less can go wrong in seeking to deliver what customers want. For example, this means that whereas most low-cost carriers charge extra for luggage, Southwest don’t. They know that the hassles associated with monitoring and charging people for this creates uncertainty and bottlenecks. If customers need to change tickets, Southwest seeks to make that easy, estimating that the costs of making it difficult for people to change are greater than the costs of allowing some flexibility. Southwest does not waste time, money and energy on seeking to offer the kind of frills that do not contribute to giving customers what they want most from them, and this helps them to stay focused on the performance goals that matter.

Staff are motivated to be efficient partly because Southwest’s systems are efficient, and also because staff have “skin in the game”: all staff can benefit from generous share ownership schemes as part of their remuneration. In this way, staff feel that they own the company. This makes them more likely to want to seek further training (which Southwest greatly encourages), be friendlier to customers, able to see where new ideas and innovations could add value, and to volunteer these ideas too.

Some suggestions

Some suggestions

-

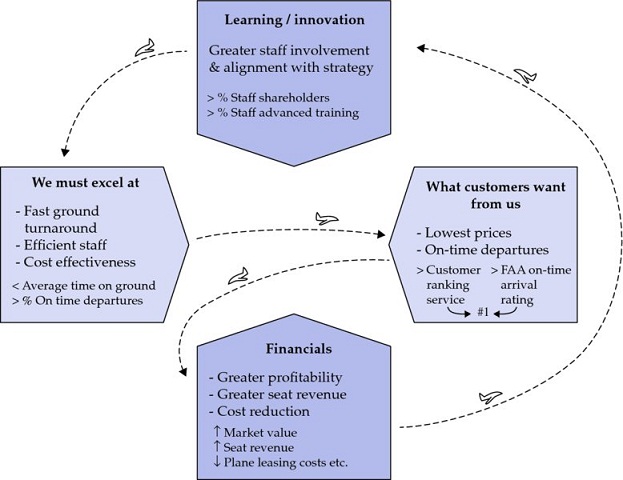

Balanced Scorecard map

There is no one best way to draw a Balanced Scorecard diagram for an organisation, but in early attempts it is useful to take a broad-brush approach and not get bogged down in detail. This encourages people to see the most important strategic elements and how they should relate to one another, creating a strategic synergy that helps the organisation stay on target to perform in the present (e.g. on-time arrival ratings; seat revenue) and develop the resources that will enable it to perform in the future (e.g. motivated and efficient staff keen to develop themselves and the company). This is the notion of “balance” that the framework, used well, can encourage stakeholders like staff to see what’s most important and, consequently, to execute the tasks that will lead most directly to good performance.

Below is an example of such a broad-brush outline of Southwest’s operating strategy in the shape of a Balanced Scorecard developed in Strategy Pathfinder’s companion book Strategy Builder: How to Create and Communicate More Effective Strategies. It is more specifically focused on Southwest’s airport operations, and it does not incorporate the importance of happy and engaged staff providing better service which is emphasised in the case above (which your drawing could make more of), but it provides you with a model you might use as the basis for your interpretation.

-

Purpose, mission and vision at the centre

As with most organisations now, it is quite easy to find Southwest’s mission and vision statements. Simply searching “Southwest vision statement” online will take you to the appropriate place in the company’s “Investor Relations” pages.

Some firms will favour either a mission or vision. Some will have both. Others may also list “values”, statements of “purpose” or “corporate philosophies” on their websites and corporate materials, but it should not be difficult to find these simple overarching expressions of what strategic performance means for almost any organisation bar the smallest and the newest.

As of 2017, Southwest’s corporate purpose, mission and vision statements were listed as follows:

- Purpose: Connect People to what’s important in their lives through friendly, reliable, and low-cost air travel.

- Mission: Dedication to the highest quality of Customer Service delivered with a sense of warmth, friendliness, individual pride, and Company Spirit.

- Vision: To become the world’s most loved, most flown, and most profitable airline.

All of these should be consistent with what you have drawn in your answer to question 1. And placing these statements in the centre of your drawing should enable you to better see how the parts should work together toward achieving these aims in much the same way as UK supermarket Tesco’s “Every little helps” statement provides the lynchpin for all the parts of its “steering wheel” (do a Google image search for “Tesco’s steering wheel”).

-

What can we learn from Southwest?

A number of important lessons for thinking about strategic performance, including the following:

- Strategic performance can mean the achievement of many different aims, not just financial aims: customer satisfaction, staff engagement, innovation, sustainable practices and so on.

- It is up to each organisation, in collaboration with its stakeholders, to determine what performance means to it. Not being clear about this can lead to confusion, misdirected effort, under-performance and failure.

- Good performance means a variety of elements working together to increase synergy. The parts of an organisation cannot be viewed in isolation. All should contribute in some way to corporate performance.

- An organisation cannot be all things to all people, so performance requires focus. Southwest cannot be the most luxurious airline or fly to the most destinations and achieve its goals. They have consistently performed well because they understand what their targeted market segment wants most and put everything into providing those things better than their rivals, now and for the future.

11-2 Harley-Davidson: Risky Image, Livewire Response, Peak Performance?

Harley-Davidson may be the world’s most iconic brand. No mainstream brand has conveyed such a clear image over the past 50 years: an image of rebellion, danger and being an outsider. This edgy petrol-head identity has attracted a legion of incredibly loyal, mostly white, mostly male, and increasingly mostly middle-aged and elderly, fans. While it would be difficult to get a precise measure, it seems a safe bet that Harley is the world’s most tattooed brand (a survey in 2004, reported on in the book BRAND sense by Martin Lindstrom, asked people which brand they would most like to have as a tattoo: Harley-Davidson was a clear winner).

Appreciating the importance of the brand’s mystique and their customers’ loyalty, the company has been fiercely protective of maintaining this brand image. Harley even became the first company to try and patent a sound (the noise a Harley engine makes) to protect this from imitators.

However, an ESTEMPLE analysis would quickly identify a number of threats that have emerged as Harley’s identity has increasingly fallen out of alignment with the broader environment in which the company operates: changing social mores, ethical and ecological concerns are certainly not in step with Harley’s products and the way they have marketed them in the past.

Enter the LiveWire: Harley-Davidson’s new battery-powered e-bike.

Not only is the LiveWire Harley’s first non-fossil-fuel driven bike, it is smaller, lighter and quieter than a traditional Harley. It features a new digital display between its handlebars to indicate speed and serve other functions and there is no clutch on the left handlebar, since there are no gears. And while the company certainly doesn’t want to disenfranchise their traditional customers, they recognise that they need to expand their traditional customer base.

According to CEO Matt Levatich, the LiveWire initiative does not signal that Harley will be less concerned with its core customers who want old-fashioned motorcycles. “We’re absolutely not abandoning any of that,” he said. “We’re going to continue to invest in great traditional Harley-Davidson motorcycles. LiveWire has nothing to do with that. It’s all of that, plus opening the doors to some people that are maybe on the outside of the sport, on the outside of the brand.”

Just who Harley is targeting is indicated in the LiveWire’s first product placement. The 2016 Marvel blockbuster, Avengers: Age of Ultron, features a prototype version of the bike driven by the sleek leather-clad super hero Black Widow, played by actress Scarlett Johanssen.

While the LiveWire is a novel concept for Harley, the company is coming late to the e-bike market, behind companies like Zero Motorcycles and Polaris Industries. But it is betting that its dominant market presence in traditional motorcycles and its marketing clout mean it can afford to give others a head start.

The delay is not due to the mechanical performance of the prototypes which Harley has been promoting at trade shows and other events. This is impressive: the LiveWire can go from zero to 60 in about 4 seconds, and can reach up to 92 mph. The delays are due to other teething problems.

While the company recognised from the get go that an electric bike could never possess that distinctive Harley growl and rumble, engineers aimed for a sound reminiscent of the whoosh of a jet engine for the LiveWire. In reality, though, this has been difficult to achieve convincingly. Furthermore, unlike regular commuters who have gravitated to e-bikes, Harley owners like to take their bikes for long rides (a weekend ride of 400 miles is not unusual for some Harley riders). So Harley has recognised a need to provide an e-bike that stays charged longer the current standard of 50 to 100 miles.

Levatich said Harley would await improvements in battery technology before they go to market, so the LiveWire can have the performance he believes buyers expect. “Will we get to that Nirvana that customers say they want? Probably not,” he said. “Will we get close enough? I believe we will.”

In late 2016, Levatich was vague in an interview with The Wall Street Journal about when the bike would be launched. It shouldn’t be expected “in the next couple of years but it’s not past 2020 either, unless we run into some impossible barrier”.

11-3 Handi Ghandi Curries: No Worries?

There are many chains of Indian takeaway restaurants throughout the world, and the chain created on Australia’s Gold Coast is not too different from most of them – apart from its quirky name and catchy advertising.

Handi Ghandi Curries has grown quickly through franchising and there are now stores using the Handi Ghandi Curries name and logo being opened in Australia’s major cities. The company, which primarily delivers a large range of Indian-style curries in American-style Chinese takeaway boxes, uses the slogan “Great curries … No worries”, has a logo featuring a cartoon image of Mahatma Gandhi tucking into a Handi Ghandi box, and a jingle featuring a man singing “I am Handi Ghandi, eat my curries” in an accent like that used by the actor Ben Kingsley in the popular film version of Gandhi’s life.

However, as the company has grown, its exploits have attracted more attention, and it turns out that the Mahatma’s family is not at all pleased with this use of his image. His great-grandson Tushar, managing trustee of the Mahatma Gandhi Foundation, was outraged that the Gandhi name had been used to sell meat curries (even though it had been misspelled). Mr Gandhi described the act as offensive, saying it went against all the renowned vegetarian’s beliefs. Especially offensive was the sale of beef curries by Handi Ghandi, as cattle are considered sacred to Hindus.

On 16 June 2005, The Calcutta Telegraph reported the story as follows:

The Mahatma has been many things to many people. But when an Australian company portrayed him as a cook to sell beef curry, his great-grandson decided things had gone too far. Tushar Gandhi today requested Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to take up the matter with the Australian Government and stop the New South Wales-based Handi Ghandi Pvt Ltd from abusing the Mahatma’s memory. Tushar Gandhi would have had no problems as long as the Mahatma sold the company’s samosas, vegetable curries, parathas, naans, chutneys, salads, and biryanis. It was the Beef Madras, beef vindaloo, lamb rogan josh, Bombay Fish, and butter chicken that got his goat.

“I have nothing against non-vegetarian food,” the relative said, “but using Bapu’s [Gandhi’s] image to sell meat curry is too much. I probably would not have raised the issue if the company had promoted vegetarianism and health food.”

The great-grandson has written to the Prime Minister’s Office, the Ministry of External Affairs, and the Union Law and Judiciary Department to take the issue up at a diplomatic level with Canberra. “Bapu’s image is protected by the Indian Constitution,” he said. “It is the equivalent of a national flag or any other Indian emblem (in sanctity).”

Although Mahatma Gandhi’s name and image are protected under India’s Constitution and national emblem laws, they are not protected outside of India, so legal action could not be taken in Australia. Indeed, the Handi Ghandi brand and logo were approved by and registered with the Australian trademark authorities. However, in response to the Gandhis’ protests, the company issued the following statement on its website and announced the change of its logo from a drawing of Gandhi to a caricature of a more generic Indian man.

A recent press release distributed with comments from Tushar Gandhi, the great-grandson of Mahatma Gandhi, stating his concerns over the use of a caricature contained in our company trademark has been viewed widely around the world. Our company has never at any stage intended any offence or disrespect to the great Mahatma Gandhi or his family and Indian nationals. In a sign of good faith our company has decided to alter its corporate logo.

Handi Ghandi hoped the alteration of its logo would placate the Gandhi family – but it didn’t. The Lismore Northern Star, a local paper in the area where Handi Ghandi was established, reported Tushar Gandhi’s response on 25 June:

THE great-grandson of Mahatma Gandhi has called on Northern Rivers residents to boycott Handi Ghandi takeaway restaurant chain if it refuses to alter its name. If the restaurant complied, Tushar Gandhi said he would eat the Lennox Head-based company’s curries himself. In an email interview, the Mumbai resident said he was sending an appeal to the residents.

“To those of you who work for Handi Ghandi and for those of you who are their clients, prevail on them … to change the name, remove the mis-spelt but still related name of my illustrious great-grandfather … from their brand name and stop the use of the very offensive jingle,” he said.

“May peace and joy be your eternal neighbours.”

International protests have been sparked by the company selling curries in the name of vegetarian pacifist Mahatma Gandhi. A caricature logo of the leader attracted complaints from Australian Indians and the Mumbai-based Mahatma Gandhi Foundation. Even Indian Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh has joined the protest, adding his name to a letter demanding the company drop the use of the image and change its name.

The protesters won a partial success last weekend when Handi Ghandi decided to change its logo; swapping an image of Mahatma Gandhi for a picture of a bearded man in Indian garb. But the company co-owner and managing director Troy Lister said the name would not change. “It is a legally registered tradename,” Mr Lister said.

Mr Lister has said the name of the takeaway franchise was deliberately mis-spelled to prevent it relating directly to Mahatma Gandhi.

Mr Gandhi [also] wants the people of Ballina to know that the Handi Ghandi jingle parodying the Indian accent is demeaning to Indians. “It is a racist image of the Indian accent,” he said. “[The Handi Ghandi promotion] is as offensive to us as if the name and images of Jesus [were used] to sell products or, for the British, if the Queen’s image as a sales woman [was used].” [However, Mr Gandhi] said he would be the first to thank Handi Ghandi if they complied. If Handi Gandhi changed its name “I would not hesitate to patronize their business,” he said.

Some Western media did not take these protests quite so seriously, however. Under the heading “What’s Next, Martin Luther Burger King Jr.?” CMO Magazine’s Constantine von Hoffman made light of the situation: “The family of Mahatma Gandhi is upset just because some Aussie company is using the great guy’s name and image to sell curry. Some people are just sooo sensitive.”

And the Calcutta Telegraph did point out that Tushar himself had faced public criticism in 2001 when he was accused of trying to sell the Mahatma’s image to a US-based licensing company for use in a film advertisement for a credit card. CMG Worldwide had offered $51,000 per year for the use of the image.

11-4 Post Office: Sustaining Postman Pat?

In December of the year 2000, the British Post Office announced that its corporate figurehead, Postman Pat, an animated character whose television show has been entertaining children in Britain and other parts of the world for decades, would be dropped from its promotional and charity work. (If you are not familiar with Postman Pat you may want to check him out at www.postmanpat.co.uk.) Among other measures, Post Office employees will no longer be encouraged to visit local schools, fêtes and children’s wards dressed as Pat. Instead, their volunteer work will be directed toward a new campaign to encourage literacy. In the Post Office’s defence, a press officer said that it was nothing personal: “We’re not anti-Pat. We’re just reassessing our priorities.”

These are certainly challenging times for the Post Office. Courier companies, many of them well-known global corporations, are eroding market share in what once was largely a monopoly for the Post Office. Society’s values are also changing. However, David Thomas of The Independent has put up a spirited defence for the long-serving Greendale-based postie:

I realize, of course, that judged by the ruthless, market-driven standards universally prevalent today, Pat is a hopeless case. From the moment when, just as the day is dawning, he climbs into his bright red van, his life is a catalog of professional misconduct. The Post Office was quick to confirm that his habit of letting Jess, his black-and-white cat, ride in the front of his van was a blatant contravention of health and safety procedures.

Similarly, the incidents [from his television and book adventures] that repeatedly cause post to be lost, misdirected, or damaged (one thinks, for example, of the occasion when Pat entrusts the school mail to young Bill Thompson, who promptly drops it in a puddle) would be matters requiring disciplinary action. “This is a very serious matter for a postman,” said my source.

But his most persistent failing is his seemingly incurable habit of allowing his close relationships with local folk to distract him from the swift delivery of the mail. “We do like a postman to be community minded,” I was told by the Post Office spokesperson. “But he’s there first and foremost to do his job.”

This is something that Pat would do well to remember. No one could deny his fundamental enthusiasm. He’s determined to do his deliveries, come wind, rain, or snow. He has been known to use methods as various as inline skates, sledge, and motorized super-speed scooter to help him on his rounds. But there’s no escaping the degree to which other matters are liable to intrude.

In Postman Pat’s Washing Day, for example, he begins his rounds with the observation that Granny Dryden has neglected to hang out her washing, despite the sunny, breezy weather. He stops to discuss the matter with the rheumatically afflicted pensioner, who reveals that her washing-machine has broken. Taking her dirty togs, Pat promises to deliver them to Mrs. Pottage. He then drives to see Dorothy Thompson, with whom he has tea and a slice of cake, before discussing laundry issues with the Rev. Timms, Ted Glen, Miss Hubbard, and George Lancaster.

On the following morning, Pat delivers Granny Dryden’s laundry to Mrs. Pottage and stops for yet another cup of tea, only for his uniform jacket and hat to be thrown into the washing-machine along with the old biddy’s unmentionables. This is by no means the only occasion on which Pat causes damage to his uniform (one remembers, with a shudder, the white paint he left all over his trousers on the occasion of Granny Dryden’s redecoration), despite being contractually responsible for its upkeep. But the fact that Pat has to complete his round in a tweed jacket and deerstalker hat belonging to Mr. Pottage is far less significant, in the great scheme of things, than the blatant time-wasting that has gone on beforehand.

Here is a man with no concept whatever of productivity or time-and-motion. And he is not alone. Consider Ted Glen, the local handyman. Pat visits him during his search for Katy Pottage’s lost doll. Ted has agreed to mend toys, television sets, cookers, cake-stands, bikes, roller-skates, farm machines, and house machines, “more than you could count.” Yet he has no idea when he will fulfill these contractual obligations. Even when he does, his service is abysmal. Among his goods is a watch of Miss Hubbard’s, of which he remarks, “She brought it to be fettled, last Christmas.”

The service economy has made little headway on Greendale. But is the region’s apparent refusal to move with the times really so counter-productive? Here we have a rural community that can sustain both a sub-post office (run by Pat’s superior, Mrs. Goggins) and Sam Waldron’s mobile store. At a time when households are shrinking and the increasing autonomy of individuals as social and economic units is producing side effects of isolation and alienation, Greendale folk evince a strong sense of community.

When Granny Dryden’s ceiling needs painting, Miss Hubbard provides dust sheets, Dorothy Thompson donates spare time while both Pat and Ted Glen volunteer their time to do the job for free – a task rewarded by cake and tea.

This is a world which has no need for social workers, a world that looks after its own. When Ted Glen’s design for Pat’s scooter causes chaos, people do not sue or seek compensation. Instead they take the matter to PC Selby. He, in turn, talks to Mrs. Goggins. She has a quiet word to Pat, who abandons his machine without complaint, secure in the knowledge that Dr. Gilbertson is having words with his superiors in Pencaster to ensure that they get him a proper trolley for his parcels.

People feel better living in a world like that, and there are clear economic benefits. The Government spends £120bn on social security, much of which could be saved if people were empowered to take local voluntary community action.

Pat and Ted’s working methods are less wasteful than they may appear to corporate accountants, who seem incapable of seeing the financial wood for the budgetary trees. In a country plagued by the longest working hours in Europe, staff everywhere find themselves burdened with ever greater responsibilities, while being offered diminishing professional security. No wonder that more than two-thirds of TUC safety representatives identify stress as the greatest health and safety concern in the workplace.

Stress is now the single biggest cause of absenteeism, and costs corporate Britain anything between £9bn and £19bn per annum in compensation payments, quite apart from the mammoth cost of lost days of work. The Government spends about £8bn in incapacity benefits every year, quite apart from the drain on NHS resources.

If more of us were more like Pat – or if we were allowed to be – the social and economic benefits would be enormous.

Beyond the decision to drop Pat and the publication of Thomas’s defence of Pat’s worth, there has been good and bad news with regard to the Post Office’s maintenance of its traditions. In a bid to sound more global and meaningful and relevant to today’s business world, the Post Office changed its name to Consignia. But it changed it back again in 2002, after two years of public confusion as to what Consignia stood for and public dismay that terms that they had become familiar with, like “the Post Office” and the associated “Royal Mail”, could have been discarded so brusquely and without discussion. Not long after this, however, on 20 June 2003, it was announced that the Post Office branch that had inspired Postman Pat was to be closed. The author of Postman Pat, John Cunliffe, reportedly wrote the books after listening to conversations in the Beast Banks branch in the Lake District town of Kendal. The Independent reported that Beast Banks would be one of 350, mostly rural, Post Offices that would be closed in 2003.

11-5 Aegon: Challenged by Kids

In the Netherlands, they take their responsibilities to future generations very seriously. The Missing Chapter Foundation (MCF) and UNICEF Netherlands have challenged organisations to develop and take advice from “Kid’s Councils”. The MCF is an NGO that initiates dialogue on sustainability between decision-makers, children and young professionals. Its Founding Director is Princess Laurentien van Orange – a former management consultant and a prominent member of the Dutch royal family.

Over 20 Dutch organisations have already taken up the challenge and now meet regularly with representative groups of senior primary school children to gain their insights. This YouTube clip explains how the Kid’s Councils work:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hR7v4K9KMbU.

Aegon, a financial services company, recently set up its own Kid’s Council. They first met at Aegon’s Corporate Center in the Hague in 2015 to consider how Aegon can help people think about their future and what might help people save money for this. They worked together with Aegon’s CEO, Alex Wynaendts, and other employees using mind-maps, question sessions and discussion.

Bartelt Pekelharing, Aegon’s Project Manager, explains: “We chose to work with the Kid’s Council because children are more creative and will have a fresh look into things. And also, they’re the next generation – so when you think about the long term, it’s also their problem.”

This weblink takes you to further explanations and some video clips reporting on what a Kid’s Council is doing with Aegon:

http://www.aegon.com/en/Home/Investors/News/News/Archive/Kids-Board/.

And this YouTube clip shows Aegon’s Kids Council reporting their findings back to Aegon in a session moderated by Princess Laurentien:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aoc-KSP6SZY.

Initial feedback from the kids involved in these councils is interesting. When asked to reflect on their experience of how adults solve problems, some kids said that they thought that adults often try and fix everything all at once, jumping right into the middle of a situation and being overwhelmed by the complexity, rather than just focusing on one small thing at a time and working on that, as they would.

This difference of approach is reflected in the advice given by the Kid’s Council advising an organisation on how to reduce water consumption in the Netherlands, currently a big issue there. The average shower time in the Netherlands was nine minutes. The Kids thought this could be reduced and together they came up with a campaign called “Just Take 5” to encourage people to think about taking less time. When the adults wanted to wrap other initiatives around this, the kids advised against it. Just keep it simple to start with – don’t confuse things, was the advice.

Princess Laurentien is advocating for more organisations to take up the Kid’s Council challenge: “Time and again I’m impressed by the insights kids have in processes, responsibilities and behavior. They present some surprising links and see the smallest details. It is this combination that proves valuable for new solutions. Their observations are sharp and without judgment.”

Writing your own “strategic performance evaluation” case

Writing your own “strategic performance evaluation” case

Refer to the section “Using Strategy Pathfinder for Assessments and Exams” at the end of the book (see p. 385). Under “the Mini Case” and “the Briefing Note”, guidance is given about how you can create your own case. You may already have an interest in organisations around you that you would like to understand in more depth – and this is a good vehicle for that purpose. There are also a large number of websites that highlight interesting organisations that you might want to find out more about. For instance:

- Websites for national newspapers

- Forbes

- TechCrunch

- uk.businessinsider.com

- www.fastcompany.com

- www.huffingtonpost.com.

It is also worth noting that in the UK there is an excellent website for company information at Companies House. The address is https://beta.companieshouse .gov.uk/.

Evaluating the strategic performance of an organisation should prove interesting if you adopt the different perspectives provided in the chapter (to see, for instance, if your financial evaluation is similar to your strategic evaluation). For public companies, data should be freely available on their financial and accounting performance over time and there should be enough information in the public domain to enable you to make a strategic assessment and take into account issues such as sustainability, ethics and risk. For private companies, obtaining financial performance data is likely to be difficult if not impossible. It is possible to attempt to identify proxies for their performance but this is a technical challenge, so financial performance information is only likely to be accessible first hand or through direct enquiry.

![]()

Notes

- 1. “Doing a Ratner” and other famous gaffes (2007) The Daily Telegraph, 22 December.

- 2. World Commission on Economic Development (1987) Our Common Future, Oxford University Press: 43.

- 3. Pfeffer, J. (2010) Building sustainable organizations: The human factor, Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(1): 34–45.

- 4. Kaplan, R. S. and Norton, D. P. (1992) The Balanced Scorecard: Measures that drive performance, Harvard Business Review, 70(1): 71–80.