Chapter 1

![]()

What Is Service Excellence?

We have to give people a reason to come to us and keep coming back. We are going to treat them like royalty. We are going to wow them and service the hell out of them and have the customers believe that the only reason we got up in the morning was on the chance that they would grace us with their patronage.

—Paul Saginaw, Zingerman’s cofounder

DO WE NEED LEAN IN SERVICES?

Has anyone reading this book had a service horror story you would like to share? Put another way, is there anyone who has never had a terrible, frustrating experience? Recalling these abysmal experiences is easy. We wonder how many examples of excellent service our readers can come up with. Have you called your cable service provider, or your electric company, or the Internal Revenue Service, and quickly talked to a real person who graciously and efficiently solved your problem? The answer may be that service was excellent when you were dealing with a salesperson, but terrible once you made the purchase and then had a problem.

Do power outages get efficiently resolved? Is road repair efficient? When was the last time you remember passing a road repair operation and seeing people actually working? Anyone waited on the plane parked on the tarmac after the pilot explained there was a minor issue that would take minutes to fix only to find that nobody had arrived at the plane for 30 minutes or more? (I [Jeffrey] am doing that as I write this.) Read any interesting magazines in an office of a doctor, dentist, or your auto repair facility while you looked at your watch wondering when you would be served? Waited for a contractor or inspector on that exciting new construction project?

Accenture conducted an enlightening study of the life insurance industry—that bastion of service excellence. According to the study, about $470 billion of insurance business globally will be up for grabs because of unhappy customers. According to a survey of more then 13,000 customers in 33 countries, 16 percent (less than 1 in 7) said they would “definitely buy more products from their current insurer.” Only 27 percent rated highly their insurance provider’s “trustworthiness.”

We have worked with many service providers that started the practice of surveying customers—rental cars, payroll contractors, information technology services, cell phone providers—and the story was the same in all cases. The companies were surprised to learn how unhappy their customers were. Customers were not only dissatisfied but angry and frustrated.

This book is about “service excellence,” which for so many of us sounds like an oxymoron. Most service organizations are so far away from anything resembling adequate basic service that excellence becomes an empty slogan. Yet simply by measuring customer satisfaction, organizations repeatedly find ways to get better. Just focusing attention can make a difference. Excellence goes far beyond focusing attention. It requires disciplined practice and continuous improvement throughout the enterprise. Think of this as a long-term vision that might at the moment seem unattainable but provides the right direction.

In this chapter we will define service excellence, starting with two contrasting stories comparing a reputable appliance retail outlet that is pretty good with an automotive dealer network truly on the path to excellence. We will then begin to define service excellence, starting with these questions: What do we mean by service, and how is it different from manufacturing?

TWO CUSTOMER SERVICE STORIES

Gas Cooktop Purchase and Installation

It was almost Mother’s Day, and I had a great idea. I would surprise my wife, Deb, with a gas cooktop as a Mother’s Day gift. When our house was built, we’d selected a Jenn-Air electric cooktop, inset in a granite-topped island. Now Deb wished we had chosen a gas cooktop, as she preferred the consistency of the gas flame for cooking.

Wondering if Jenn-Air made a gas model that could replace the electric one and that would fit in the island, I measured the size of the opening of the insert, went online, and within minutes found the exact model number for the Jenn-Air gas cooktop that would fit. I then debated shopping around on the Internet to see where I could get the best deal, but decided instead to purchase the cooktop from the most reputable appliance store in town, as it specialized in Jenn-Air products. It wasn’t the cheapest alternative, but I wanted to make sure I got the best installation and experience.

I drove to the store and waited at the front desk while a salesman fiddled around with the computer trying to locate the part with the model number I had provided. It seemed that the salesman, hunting and pecking on the computer key-board, was typing a lengthy article, not selecting an item with a mouse click. I continued to wait patiently, and the salesman told some interesting stories as he continued searching the computer.

Finally, the salesman found what he was searching for and exclaimed, “You’re in luck! We don’t normally have that model as part of our regular stock, but it is available, and we have a truck coming from the warehouse in two days. If we order the cooktop now, we can get it on that truck!” The salesman showed me a similar model in the store, and I agreed to place the order. The salesman began hunting and pecking on the computer keyboard again. By now, about 15 minutes had passed, and tired of waiting, I started fiddling with my iPhone. After at least another five minutes, the salesman finally printed out an order. “The computer seems to be running very slowly today,” he apologized.

The salesman then explained that an installer would need to visit the house prior to the installation to determine what parts would be needed for the new gas line and to estimate labor charges. I agreed that that would be fine, and the salesman then called up yet another computer program. Typing madly, he finally located the installer’s schedule, and lo and behold there was an opening the next afternoon. I wouldn’t be available at that time, and although it would spoil the surprise, I decided to let the cat out of the bag about the Mother’s Day present and called Deb to see if she could stay at home to wait for the installer. Deb was available, so the salesman spent another few minutes working on the computer to schedule the visit. After I paid the 50 percent deposit, the salesman entered some final information and printed out the receipt. By this time, I had spent half an hour at the store. By the time I got home, the whole trip had taken me about one hour.

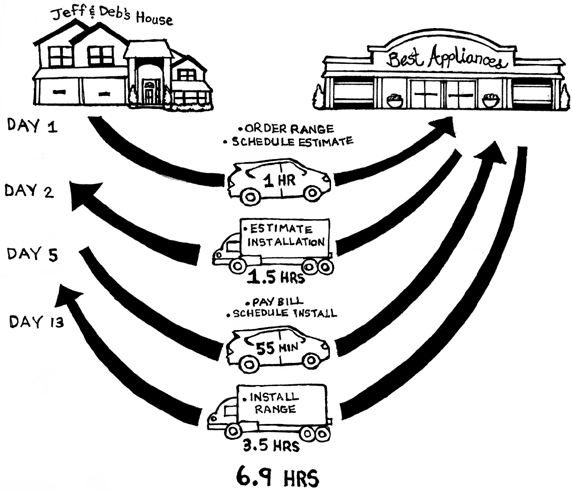

(Total lead time = 1 hour; “lead time” is the elapsed time from the start to the end of a process.)

The next day, Deb stayed at home. After about one hour of waiting, two installers arrived and proceeded with the estimate, searching through the basement and taking many measurements. It took about 20 minutes for the installers to handwrite the type and quantity of the materials they would need (gas pipes, adapters, valves, etc.) and calculate the estimated labor hours. Total time for the installation estimate, including Deb’s wait time, was an hour and a half.

(Total lead time = 1.5 hours)

I was a bit surprised to find out how much the installation would cost, but it was a Mother’s Day present, so the next day I got back in the car and drove to the store to complete the order and pay the balance. The salesman I had previously spoken with wasn’t in, so I explained the situation a second time to a different salesman. This salesman asked me for much of the same information that I had provided on the first visit—item name; model number; my name, address, and telephone number—and began typing furiously. This time, however, the computer screen was facing me, and it was immediately clear why this was such a lengthy process. The user interface looked as if it hadn’t been updated since the 1980s, when computer programs were written in Basic. The salesman had to scroll down line by line, adjusting the cursor each time, and type in every bit of information, including part numbers, each of which seemed to be about 15 characters long. Every time the salesman finished typing a field, he had to press Enter and wait while the cursor blinked on and off. While this was fascinating to watch for a minute, I was soon back fiddling on my iPhone.

After about five minutes of typing, the salesman looked confused and said to me, “Seems like the cooktop is already here at the store. We can go ahead and schedule installation if you’d like.” The salesman then called up a crude-looking schedule and found that there were openings on the following Tuesday and Wednesday. As I was going to be traveling, I again called Deb to check on her availability. Deb could stay at home the next Tuesday morning to meet the store’s half-day time window, so the salesman scheduled the installation. After a few more minutes of typing, the salesman was ready to print the installation order and receipts. He tried to print out the documents but looked frustrated and said, “It appears we have printer problems. Let’s move to the front desk.” At the front desk he was able to print out the four documents. I paid and signed one document, and the salesman offered to staple the three new documents to the two that I already had. After spending 25 minutes in the store, I was again on my way home. Total time to schedule the installation and pay the balance was 55 minutes.

(Total lead time = 55 minutes)

On the day of the installation, Deb waited excitedly for the installers to arrive at 9 a.m. As was their policy, they called in advance to let the customer know that they would be there in 15 minutes, but since they called my cell and I was in Switzerland on a speaking engagement, Deb had no way of knowing that. Once the installers arrived, they efficiently completed the complex job of running gas pipes and wiring above the drywall ceiling of the finished basement. They expertly cut a hole in the shelf of the cabinet below the cooktop to install the gas-firing mechanism. Deb was impressed with the installers’ expertise and professionalism. The experience wasn’t totally perfect, however. The installation was noisy. Deb spent 3½ hours listening to loud banging and other noises. It was dusty, too. The installers made numerous trips back and forth between their truck and the house, leaving the garage door open the whole time. Deb had to clean the garage after they left. And the smell of gas spread from the utility room, through the finished basement, and up the stairs into the living room. But by 12:45 p.m. the installation was complete, and Deb was thrilled to have a gas cooktop that was properly installed, looked great, and worked! She tipped the installers, and they were on their way.

Later on that evening, however, Deb and I noticed that there seemed to be a continuous flow of air blowing through the new cooktop into the kitchen. Searching for the source of the problem, we found that an outside duct cover had been forced open by a nail, probably by painters the summer before to prevent the cover from getting stuck closed by paint. We removed the nail, and the problem was solved. My Mother’s Day present was a rousing success!

To summarize our experience:

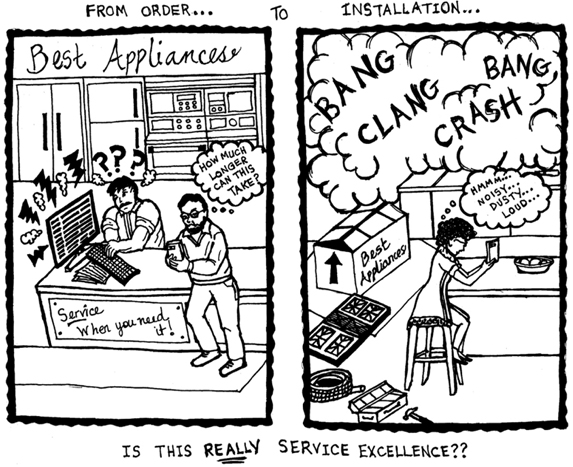

![]() Total installation time: 3.5 hours (see Figure 1.1).

Total installation time: 3.5 hours (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Appliance service lead times

![]() Total work time for the entire process (both value added and non-value added) including the installation: 6.9 hours.

Total work time for the entire process (both value added and non-value added) including the installation: 6.9 hours.

![]() Total lead time from start to installation: 13 days.

Total lead time from start to installation: 13 days.

After the installation was complete, neither Deb nor I received any follow-up calls or customer satisfaction surveys from the appliance store. We probably would have said everything was fine.

Volvo Automotive Service & Repair

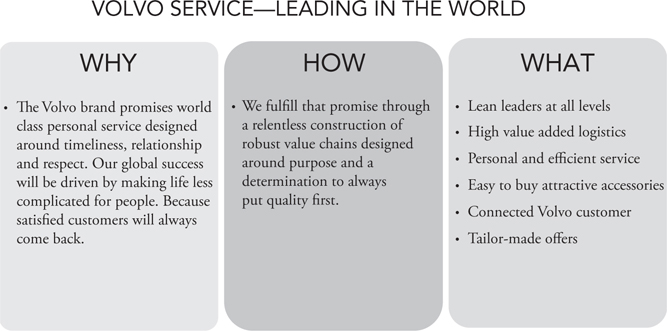

Like the appliance store, Volvo dealerships in Sweden had a solid reputation. But simply having a “solid reputation” was not satisfying to Einar Gudmundsson, vice president of Customer Service. A devout student of the Toyota Way, Einar brought many of its ideas to Volvo. He and his team crafted a bold vision to become the world leader in automotive dealer service (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Volvo service vision

Einar started out by determining exactly what Volvo customers valued in automotive service. He had learned from a survey of 100,000 customers that the top three things they wanted were (1) positive relationships, (2) time reduced to the minimum, and (3) good problem solving to service and repair their cars.

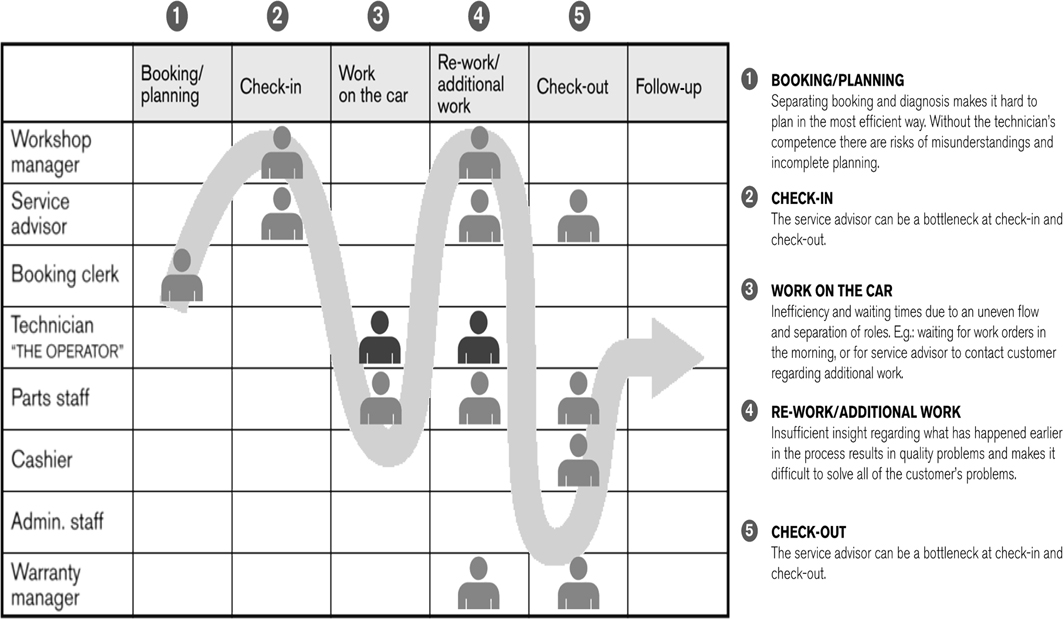

One place Einar and his team focused on making a large difference in service was in the automotive repair bays. In the old system, a typical experience was similar to the appliance store case. A customer needing a repair would call the dealership. A receptionist would schedule a time for the customer to drop the car off to have the problem diagnosed. When the customer picked up the car, he would be told what the problem was and then have to schedule another appointment and bring the car back to be worked on. When the car was repaired, he would have to walk to the cashier’s office and pay and then walk back to the service area to retrieve the car. Generally, the car would stay at the dealership for an entire day for each of these visits, and the customer would not have a car to use to get back and forth to work. There was a lot of queuing and waiting in the process as the customer was handed off from department to department, and often errors were made because of poor communication (see the original process flow in Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Customer value chain in traditional workshop

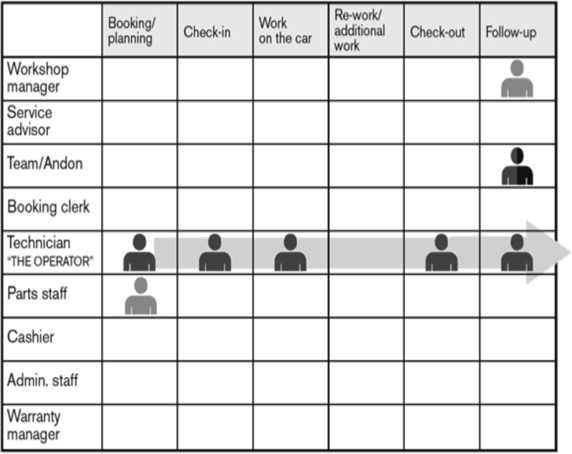

One of the early steps taken by Volvo to improve this process was to develop a role called the personal service technician (PST). Under the PST there were, in theory, no handoffs, and the customer dealt with the same person, a technician, from initial call to payment, reducing errors and reducing the time that the customer spent waiting (see the improved process in Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Customer value chain in one-hour stop workshop

As VP of Customer Service at Volvo, Einar had taken this a step further to what he and his team called “one-hour stop.” A core principle of lean is one-piece flow, and they asked, “What would it look like for the customer to flow from step to step without interruption?” The goal was to handle as many customers as possible within their own guaranteed one-hour time slot—starting from the first time the customer entered the dealer with the car until the customer left with a repaired car. They found that the PST system had limitations and that customers often did not reach the technician when they called in because the technicians were busy. They also found that the technicians often sent the customers to the cashier to pay at the end of the service, instead of taking the payment themselves. Customers didn’t like either of these conditions.

Making one-hour stop a reality would require many changes beyond creating the PST role. One thing that Einar and his team learned was that to have a short and reliable lead time to repair a car, they needed two technicians in a repair bay working together. A single technician had to walk around and around the car to work on it, while having two technicians meant that each one could work on a side. They could then plan out the steps each would follow, which Toyota calls standard work. It was also important that they had the right parts and tools prepared for them in advance of the job, like a pit crew for race car drivers.

Einar’s team had success in developing strong dealerships that could achieve one-hour stop, and customers began showing up without an appointment. Customer satisfaction rose. His team went from dealer to dealer making a proposal: “We will more than double your productivity of each repair bay based on teams of people working in each bay.” Often a pair of Einar’s technicians could do as much work as three or four of a dealer’s technicians, and dealers, which were landlocked, could more than double capacity without investing in any new brick and mortar.

In 2013, recognized for his great progress transforming to lean in dealerships and the corporate offices, Einar was asked to personally run, on a full-time basis, an average-performing dealership. His goal quickly became to make it the most profitable dealership with the highest customer satisfaction ranking using what he had learned from the Toyota Way.

Here is how one-hour stop works now in Einar’s dealership: fourteen technicians are organized into two teams of three pairs, with a lead service technician for each team. Each team has three service bays. When customers call in, they talk directly to a technician who does his best to diagnose the problem over the phone. The technician then calls the Volvo parts warehouse (which also was reorganized using Toyota-like principles) and orders (two days in advance) the parts needed. If the technician thinks it might be one of two problems, he orders two sets of parts. The parts come on a gray tray, arranged for that particular job. The pair then goes to work doing the repair. When the repair is complete, the technicians meet with the customer to explain what was done and collect payment. Customers can now spend the one hour waiting for their car to be repaired in a pleasant “living room” equipped with televisions, Wi-Fi, high-quality coffee, soft drinks, and snacks—all free—located beside the sales floor. While customers are waiting, the salespeople have a chance to interact with them, and this has led to increased sales.

The technician teams function mostly autonomously, though they have weekly coaching meetings with management. Each week they review key performance indicators on team target boards showing the performance of each pair. Measures include percentage of time the phone is answered the first time a customer calls, percentage of accurate diagnoses based on the phone call, time to invoice the customer, percentage of time the customer paid the PST versus had to go out to the cashier, and percentage of rush orders on parts versus parts delivered by schedule. The service performance measures are continually being updated with the team. It is a no-blame culture, and problems get solved. In fact, the technicians run the meetings, with management remaining quiet and then doing some coaching afterward. Managers even get graded by the technicians on the quality of their coaching.

Over time the teams have learned how to handle various common types of service issues, and within 1½ years they were up to completing 80 percent of the jobs in less than 1 hour—from the time the car first arrives until the customer drives away in the repaired car.

Also after only 1½ years, Einar’s dealership moved from the middle of the pack to one of the top 10 dealerships in Sweden. Profits have increased significantly, and the company has doubled the use of each service bay. New construction was planned to actually reduce the number of service bays, cutting capital costs per repair.

Here is a summary of the results achieved using one-hour stop in Volvo dealerships in Belgium, Spain, and Taiwan:

![]() Only half the work bays needed for a given quantity of repairs

Only half the work bays needed for a given quantity of repairs

![]() Sold time per work bay up 114 percent to 193 percent

Sold time per work bay up 114 percent to 193 percent

![]() Two to three times the productivity per repair worker

Two to three times the productivity per repair worker

![]() Three to four times the profit as throughput increases and cost per repair drops

Three to four times the profit as throughput increases and cost per repair drops

![]() Half the walking steps of technicians

Half the walking steps of technicians

![]() A rise in customers’ ratings of service as very good or outstanding, increasing from 74 to 83 percent, with the main change occurring in the “outstanding rating” from 31 to 41 percent

A rise in customers’ ratings of service as very good or outstanding, increasing from 74 to 83 percent, with the main change occurring in the “outstanding rating” from 31 to 41 percent

One of the more interesting findings is the increase in customer satisfaction ratings. It is not surprising that it went up, but it is surprising that it was so high to begin with. In the traditional system 74 percent of customers rated the service as “very good” or “outstanding.” Yet it was very inconvenient and time consuming for them compared with the new approach. This suggests that customers tend to adapt to mediocre service and will then appreciate a new level of service that in turn becomes their new expectation.

Was it difficult to create the change in culture necessary to institute one-hour stop in the dealerships? There was certainly some consternation about making these radical changes in each dealership, but after the fact the changes were greatly appreciated. For example, the customer service manager in Belgium said: “There is a much better use of the customer’s time. There is also better communication, as technicians explain things directly to the customer. The customers react very positively.” One service technician in Spain said: “For me, the opportunity to deal directly with customers is the main benefit. It builds trust and creates a stronger, more personal relationship.”

And the results showed up in profits. While Einar was VP, the customer service business earned $2.3 billion with $800 million in profit.

Comparing the Two Cases

Overall, both organizations seem to be doing well. The appliance store has a long history as a stable local business and has survived ups and downs in the economy. At some points, Volvo has struggled and almost gone out of business. But at this point in its history, Volvo customer service is working tirelessly toward service excellence, whereas the appliance store appears to be stagnant.

Has stagnation hurt the appliance store’s business? It seems that customers adapt and view a given level of service as normal. By most standards our appliance purchase and installation experience was “very good,” and this particular store has done well for decades because of its reputation for great service. At every stage in the process, the salespeople and installers were friendly and professional and knew what they were doing, and the gas cooktop was properly installed. Overall, we were happy that we selected the store for the purchase and installation of our new cooktop, but can we really say that what we experienced was “service excellence”? When I calculated the time spent door to door on the first visit, at home waiting for the men to come to estimate on the second encounter, and door to door on the third visit, it had taken 6.9 hours between my time traveling to and from the store twice, my time waiting in the store, and Deb’s time at home while installers were planning and later installing. A total of 13 days passed from the initial order to installation. All this time to get installed the exact item that I had identified on the Internet in a few minutes prior to starting this process—and for a product already in inventory. There were some hiccups, arguably minor, but there was no indication that anyone in the store realized this or cared. After the installation, we didn’t receive any type of follow-up call from the store or a customer satisfaction survey. Since we did not complain about the service experience, perhaps the store assumed that all was excellent.

The Toyota Way encourages us to envision the ideal state and then compare it with the current condition. It is only if we think of an alternative that is much better than what we have that we become dissatisfied. What if I could have simply phoned the appliance store since I knew what I wanted, talked to a service technician, described the situation, and had the service technician come out with the new cooktop and install it? Now in many cases this could be difficult: for example, estimating the required length of the gas pipe and connectors and estimating the time and labor costs. But perhaps a service tech could have talked me through the measurements that were needed over the phone, and I could have sent some photos with my smartphone for the technician to look at. Then, like the Volvo dealer, perhaps it would have been possible to have the unit delivered and installed within one or two days.

And consider the installation experience. Although it was professionally done and the installers had obvious craft knowledge, was it really necessary for them to make trip after trip back and forth to the truck over a number of hours, leaving the garage door open the entire time? Would it have been possible to have the adaptability to schedule installation when the installers could be let in to the house but family members did not have to be at home the entire time? Was it necessary for the installers to leave our house smelling of gas? Could they have checked the venting and noticed the vent was stuck open? (see Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5 Some weak points in Jeff and Deb’s appliance service experience

Disclaimer: This is an exaggerated satirical view of a mostly positive experience.

And what about the call to let us know that the installers were on their way? The call ended up going to me in Switzerland just before I was going onstage to speak, so I didn’t answer. What if store policy had been not to go to the installation site if the customer didn’t answer the call? Deb would have been waiting all morning without a way to know why the installers hadn’t arrived. A major problem in service processes is having the best method of contacting clients and having an idea of whether they will be available for a call. Can this problem be fixed?

Karyn has experienced this while working in several service organizations. At a third-party payroll processor, this was a common problem that usually happened on a Friday. The person making the delivery was required to call the customer before leaving the payroll checks so employees could get paid. When the driver would call the number the customer provided but the customer didn’t answer, the delivery service couldn’t complete the delivery process, so the driver would call the customer service representative to check the number. The customer service rep would then frantically call every number on file and also send an e-mail. If the customer didn’t respond, the delivery was not made, and employees didn’t get the checks they expected. When the customer arrived back at work on Monday and found that the employees hadn’t been paid, he or she would call the customer service representative and be extremely angry. Even if the rep could find a polite way to say that the number the customer provided did not work, there was never a happy ending. The customer didn’t give the wrong information; conditions just changed that the service provider was not aware of, and there was not a clear understanding between the service provider and customer of when a call would be made and who would be available to receive it.

Karyn has also encountered a similar situation in insurance claims. The insured provides an address to send claim checks to and then moves. The insurance company doesn’t know that and continues to send checks to the address on file. The insured is then upset when the checks are not received.

“Good” companies do the best they can. They believe that since they cannot anticipate everything that can possibly go wrong, they cannot be responsible for what their customers do. Excellent companies continue to work to find ways to improve in order to solve these problems, and they never blame the customer!

Volvo dealerships in Sweden had a fine reputation prior to lean. Customers needing car repairs brought their cars back to the dealership multiple times and thought it was “good service.” But once they experienced one-hour stop, they would not want to go back to the old system of multiple phone calls and visits. In fact, our guess is that once customers experienced one-hour stop, they would be very unhappy if Volvo reverted to the old system.

It is well known in psychology that satisfaction depends as much on expectations as reality. You can lower satisfaction either by failing to live up to current expectations or by raising expectations and then not meeting them. This leads to a conundrum: the better we do, the more the customers expect and the more difficult they are to please. That has been the story of the auto industry triggered by the excellence of Japanese automakers, particularly Toyota. Customer expectations are through the roof, and high quality and safety are basic expectations just to be in the game.

In 2014 automakers recalled a record 63.95 million vehicles in the United States, reflecting 803 separate recall campaigns. This was more then double the previous record of 30.8 million in 2004. General Motors led the pack with 27 million recalls, most notably the highly publicized ignition switch debacle, but all automakers recalled large numbers. One would think that auto safety was abysmal and people were in serious accidents every day because of their defective vehicles, and yet this was not the case. In fact, it was just the opposite: automotive safety was about the best it had been since the first automobiles were riding alongside horses and buggies. There were a tiny number of serious accidents as a percentage of the vehicles recalled. Almost all the recalls were preventative—in case something might go wrong. This is not bad for the customers, but it does reflect their extremely high expectations for near perfection in a machine with tens of thousands of parts that are expected to last for 15 years or more under intense wear and tear while being operated in harsh conditions.

In some ways the people at the appliance store had an easier time meeting customers’ service expectations than Volvo. They were good, and many customers like us kept coming back, even though they did not appear to have significantly improved customer service in decades. Their competitors are mostly national appliance stores with worse service, and as long as those competitors do not invest in a far better approach, the appliance store is in fine shape.

Coach John Wooden was a perfectionist in preparing his college basketball teams, who won at an astonishing rate. He said, “Success comes from knowing that you did your best to become the best that you are capable of becoming.”

This leads to a number of interesting questions: How do we define service excellence? Can we rely on customer satisfaction as an indicator of whether we are excellent? How can we change the mindset of ordinary people working in services so that they are dissatisfied with the service provided even when customers appear happy? How can we develop a culture of people truly passionate to “become the best they are capable of becoming?”

WHAT IS A SERVICE ORGANIZATION, AND HOW DO WE DEFINE EXCELLENCE?

What Do We Mean by a Service Organization?

Let’s first consider what we mean by a service. As defined by businessdictionary.com, a service is “a valuable action, deed, or effort performed to satisfy a need or to fulfill a demand.” This seems straightforward enough, and points out that it is only a service if it fulfills a customer need.

An economic perspective on service provided by investorwords.com adds further definition: “A type of economic activity that is intangible, is not stored, and does not result in ownership. A service is consumed at the point of sale.”

Now we have the notion of service as “intangible.” Moreover, we consume it at the point of sale, so customers themselves are a part of the transformation process. If we can touch and feel it and store it for later use, it is not a service but rather a tangible good. If it is a process that directly changes us as customers in some way, it is intangible and a service. Services like hair styling, surgery, psychological counseling, and personal training clearly fit this definition of something intangible consumed at the point of sale. None of these services can happen if the customer is not present when it is happening.

Google’s dictionary adds even more complexity to our definition of services:

1. “The action of helping or doing work for someone.”

2. “A system supplying a public need such as transport, communications, or utilities such as electricity and water.”

The first definition is similar to the two we have discussed, but the second adds the notion of a system that moves or transfers something that is at least somewhat tangible and storable. Electricity can be stored, and even though you do not want to hold it in your hand, it is a measurable physical entity. Bottled water is a physical product from a manufacturing plant, but a service provider transports it to a store that is a service provider. When we turn on the spigot in our home in many locations, we are getting a service provided by the water company that is pumping and treating water from a reservoir. Where does manufacturing end and service begin?

The world became more complicated with the advent of computer technology, and especially with the Internet. When I am using Amazon.com, am I using a service or a tangible product technology? Amazon itself is a system of people and technology that is supplying something tangible: software producing a user interface on our computer stored for use as we desire. We interact with the computer. Amazon data is stored in a complex infrastructure of over one million physical servers throughout the world. If we were to write our order on paper, we might say that the paper is a tangible good produced in a factory, but when we type our order into the computer interface, it is a service because it is virtual paper that was created in a software factory. Hmmm. This is getting more and more confusing.

To further complicate matters, the way services are measured by governments is as the complement of manufacturing. Services are everything that is not production of tangible goods as classified by national measurement systems. Encyclopedia Britannica online describes it in this way:

Service industry: an industry in that part of the economy that creates services rather than tangible objects. Economists divide all economic activity into two broad categories, goods and services. Goods-producing industries are agriculture, mining, manufacturing, and construction; each of them creates some kind of tangible object. Service industries include everything else: banking, communications, wholesale and retail trade, all professional services such as engineering, computer software development, and medicine, nonprofit economic activity, all consumer services, and all government services, including defense and administration of justice.

This seems both sloppy and odd. A sloppy way to define something is as everything left over except something you define: service is everything that is not manufacturing. If we etch layers and layers of bits and bytes onto a circuit board at Intel, it is manufacturing, but a cable company that transforms bits and bytes into a movie we can consume on a computer is a service. These two cases seem to have more similarities than differences. If an engineer at Intel is designing the next new computer chip that will be smaller and faster, is she in manufacturing because Intel is a manufacturing company or in a service organization because she is doing knowledge work? If she does the same work in an engineering firm subcontracted by Intel, is she now performing a service?

How Are Manufacturing and Services Different?

When we try to teach lean to service organizations using Toyota as an example, a typical response is “We do not make cars. We provide an intangible service, which is very different. How can we learn anything from an automotive company?”

Is it true that service and manufacturing companies are so different that they cannot learn from each other? Year after year, Richard Daft’s Organization Theory and Design is the bestselling textbook for organizational design courses, and he apparently thinks the differences between manufacturing and services are huge. Daft describes services as intangible and says that they cannot be saved for later use. He describes services as labor and knowledge intensive, with high customer interaction and a human element that is very important.

Some of the other distinctions seem to be based on outdated stereotypes of manufacturing. For example, Daft says the human element in manufacturing is less important than in services, but in lean, at least the Toyota Way version, team members working production are at the center of continuous improvement that drives the enterprise. Daft says longer response times are acceptable in manufacturing, but the just-in-time ideal is one-piece flow with no delays. It seems clear that from the perspective of lean, these kinds of dichotomies are oversimplifications.

Consider an electric and power company. It provides a tangible product that can be inventoried, it is capital intensive, there is little customer interaction with the power plants so the human element is less obvious to the customer, and quality is directly measurable. So in most regards it is more like manufacturing than a service.

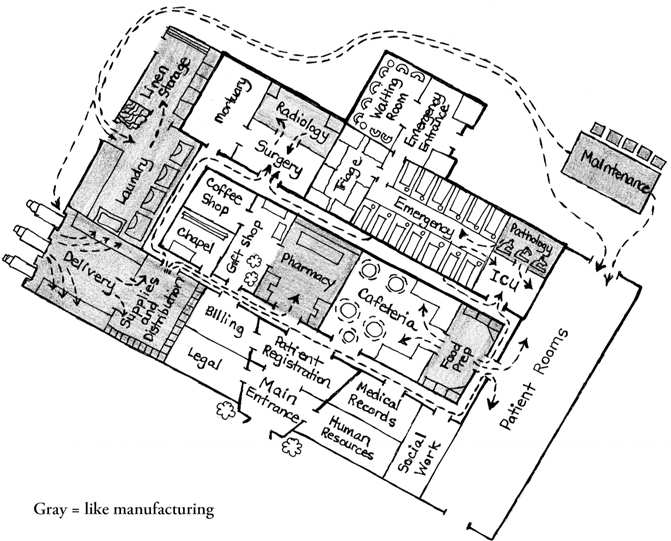

Things become even more fuzzy when we consider an entire enterprise. Think about a hospital. Karyn made a highly simplified sketch in Figure 1.6. The areas shaded seem to better fit Daft’s “Manufacturing” column than the “Service” column—areas like the pharmacy, the laundry, the pathology labs that test tissue samples, and the department that maintains all the complex equipment and facilities. Also if you consider orderlies who move people and things around the hospitals, they are very much like material handlers in manufacturing. In fact, there seems to be as much material moving about the hospital as we have seen in most manufacturing plants, and those materials need to be ordered, delivered, stored, moved to where they will be used, and disposed of. Sounding more like manufacturing all the time?

Figure 1.6 Is lean in healthcare different than in manufacturing?

I (Jeff) had an interesting experience during a visit to the Toyota Memorial Hospital in Japan. I had heard they were applying Toyota principles in a service environment. I was accompanied on a tour by two senior Japanese managers who showed me the material flow system. All materials used by doctors or nurses were carefully laid out, for example, in well-labeled drawers, with addresses for their locations. Common small items like syringes were in a see-through bag and were easy to locate. Even more interesting in the bag was a small laminated card, which Toyota calls a kanban. The information on the card includes the part number and description of the part, its location for users and location in the warehouse, and the number of syringes in the bag (see Chapter 5). As we were going through the drawers a material delivery person came by with a cart on wheels and replenished what had been used and took the cards for items that were getting low so they could replenish those on the next trip. I asked the two managers what their background was and they explained:

Before coming here we worked for many years in Toyota factories as material flow managers. One week we got notification to start new jobs on the next Monday in the hospital. We thought this was a mistake. But once we were here we saw there were thousands of materials moving through the hospital, just like parts in Toyota factories. We could apply all the same principles to make the flow more efficient and get to our customers the right material in the right place at the right time. We were able to clear out about half the warehouse and improve customer service.

In our experience, any service organization has elements that look like manufacturing, even though these may be invisible to the customers. Customers going to the supermarket see what is stored in inventory on the store shelves, usually attractively presented, and they may ask a question of a service representative, or they may directly deal with a cashier if that process has not been automated. The customers rarely see the pallets of materials in an internal warehouse that get unloaded from a truck, nor do they see the pallets broken down or the products brought out late in the evening to be restocked on the shelves and presented to the customer the next day. They do not see the routine physical processing of money. And somewhere in a back office is an accountant keeping track of all the numbers.

On the other hand, take a walk through a manufacturing plant, and you are likely to see large office areas where people are purchasing things, coordinating shipments, planning, answering customer calls, performing finance and accounting functions, coordinating insurance, and engaging in countless other “service functions.” In some large facilities there are even doctors and nurses providing medical care to employees, and there may be a pharmacy.

In short, it is often more useful to consider differences across functional groups within manufacturing and healthcare systems, or even differences in individual jobs, than it is to treat manufacturing and service organizations as different animals.

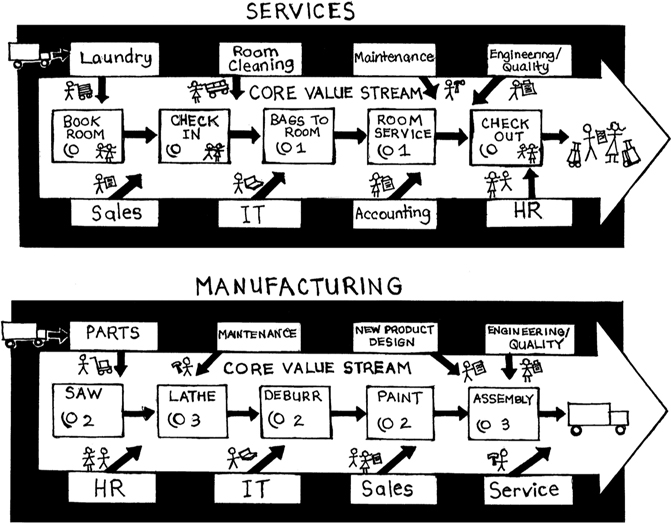

We still might define an organization in terms of the core of what it does. If the core work is to create a tangible product for sale, then we could classify it as a manufacturing business. If the core work is to service customers by making it easier to access something they need, as in the case of Amazon, or by directly improving their health or well-being, we could classify it as a service. We often see in manufacturing organizations that services are support functions to manufacturing. Manufacturing is in the foreground, and service is in the background. In service organizations, we see the customer service process in the foreground and manufacturing as support functions in the background (see Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.7 Services versus manufacturing value streams

Perhaps instead of thinking of service versus manufacturing, for the purposes of improving, it is more useful to think in terms of the complexity of the work:

![]() Customization of work. How routine (steps, sequence, time) is the operation (low) versus how specific is it to the unique situation (high)?

Customization of work. How routine (steps, sequence, time) is the operation (low) versus how specific is it to the unique situation (high)?

![]() Intangibility of work. How much can we physically see the transformation process (low) versus how much do we need abstract ways to describe it (high)?

Intangibility of work. How much can we physically see the transformation process (low) versus how much do we need abstract ways to describe it (high)?

Work complexity may vary by department, by project, by individual assignment, or even within the different jobs done by an individual. Consider a surgeon who, on the one hand, performs a routine checkup. Then think about open-heart surgery where the surgeon adjusts second by second based on the condition of the patient, the nurse is doing routine things like providing suction, and various orderlies are bringing tools and materials to the room as they are needed. We have a wide range of types of work occurring simultaneously even in the same room.

Work that is simple can be planned out in advance, and repeated cycles can be identified, timed, standardized, and rigorously taught using a clear recipe (see Liker and Meier1). This is characteristic of much of the assembly work in a Toyota plant, but we also find this work in any service organization. The Volvo dealership did most of its early lean work achieving one-hour stop and focused on standard procedures like oil changes and tire changes. On the other hand, when Einar and his team began to work on improving the sales process, they quickly noted that sales is a creative process, and they did not want to limit those skilled at this craft with long lists of standardized processes for selling. We will revisit this issue in the discussion of standard work in Chapter 6 on stable processes.

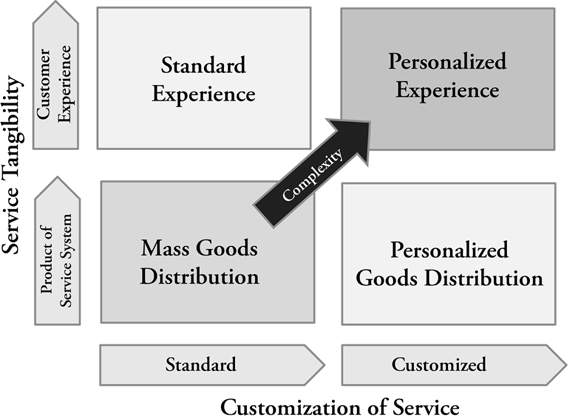

Four Types of Service Organizations

We’ve tried to sort services into four categories ranging from low to high complexity in the 2 × 2 table in Figure 1.8 based on two questions:

Figure 1.8 Classifying four types of services

![]() How customized is the service? Standard (low) versus customized (high).

How customized is the service? Standard (low) versus customized (high).

![]() How intangible is the service? Tangible product of service system (low) versus customer experience (high).

How intangible is the service? Tangible product of service system (low) versus customer experience (high).

When we look at the various combinations of these, we get four types of services:

1. Mass goods distribution. This is a service system that produces something tangible and is most like manufacturing. We are distributing a product. We are defining a product broadly to include a burger from a fast-food restaurant, a movie on our computer from the Internet, a book delivered to our house from Amazon, a seasonal beer from a microbrewery, or electricity to a building. In many cases the service organization did not produce the product, though a fast-food restaurant does prepare and assemble what it delivers, and a microbrewery is manufacturing the beer it serves us on the premises.

2. Personalized goods distribution. The system also produces something tangible that can be stored, but it is customized. Notice that these goods would typically be more luxurious and expensive versions of goods distribution such as a boutique clothing store that might make clothes to order. We would expect an actress buying a gown for the Oscars to go to a place like this. Later in the book we will talk about an exceptional software development firm that only creates customized software for a specific client. The firm spends a great deal of time and direct observation to understand how the customer currently works and how the software can function smoothly and easily to accomplish its objectives.

3. Standard experience. This better fits the definition of service as intangible, something that cannot be stored, consumed at the point of sale, with direct interaction between the service provider and customer. There is some variation in the service but it is pretty much standard across customers. We go to the bank to deposit a check and have direct contact with a teller. We go for a routine dental cleaning. Or heaven forbid, we have to call our cable company because we have a question about our bill. In these cases we are one of a long line of customers getting a very similar service. Sometimes, however, there is something special about our case, and it shifts from a routine transaction to personalized customer service. For example, the cable company representative cannot easily troubleshoot over the phone why our service is not working and must send someone out to investigate.

4. Personalized experience. This is also intangible, but it is customized and usually more expensive and luxurious. I have had a personal trainer come to my home, and each workout was customized to what the trainer thought I needed on that day. The trainer had a college degree in exercise science and a broad understanding of anatomy, muscle groups, and the impact of different types of exercises on the body. The cable repair person who comes out to our house to troubleshoot the problem is another example. The famed hair stylist that will study each client to create a unique hair style to fit that person is providing a personalized service.

As a general rule, as we move from mass goods distribution to personalized experience, the service becomes more complex. By complexity we mean there is a higher level of tacit knowledge involved—knowledge that is learned through repeated experience and cannot be easily documented as a standard recipe.

In Figure 1.9 we give examples that might fit in each cell. Any typology is an oversimplification, and this one is no exception. Any complex organization provides a variety of services that fit into more than one cell. There are call centers in cable companies that handle standard inquiries (standard experience) and also solve complex customer problems (personalized experience).

Figure 1.9 Examples of four types of services

The purpose of the model is to provide a starting point to think about the approach to improvement that will be needed. We will see in Chapter 6 on improving processes that the more conventional approaches to lean methods, like developing a documented standardized process and developing a timed rhythm to the work, can be more easily applied to “mass goods distribution” and needs more adjustment to apply to a “personalized experience.”

So What Is Service Excellence?

We have dissected and bisected services to the point that the concept is barely recognizable as a distinct category. Yet we still need to define service excellence.

The starting point is the same for manufacturing and services—the customer. What does the customer experience? How satisfied is the customer? To what degree are we enhancing the life of each customer?

The process of understanding the customer and properly designing the service is similar to creating excellent product design. We must understand what customers expect and then go beyond that, giving them the unexpected. As Henry Ford quipped, “If I asked people what they wanted they would have said faster horses.” We cannot expect the customers to know what would address their need. They are not the designers of the service and are generally limited by their own experiences.

Once the service is designed, we need to deliver on time, when the customer wants it, right the first time. In this sense customers’ needs are the same for all four quadrants of our service typology. Yet there are some differences. Roughly speaking, beyond quality and timeliness, customers for each type want:

![]() Mass goods distribution. Major customer desires are functionality, reliability, cost, and convenience.

Mass goods distribution. Major customer desires are functionality, reliability, cost, and convenience.

![]() Standard experience. Customer desires are similar to mass goods distribution with the addition of the human touch in interacting with the customer. We expect efficient service delivery that addresses our need at low cost, and we want to be treated respectfully.

Standard experience. Customer desires are similar to mass goods distribution with the addition of the human touch in interacting with the customer. We expect efficient service delivery that addresses our need at low cost, and we want to be treated respectfully.

![]() Personalized goods distribution. Customers want something special that they cannot get from the average company and that distinguishes them from the masses. It should solve their unique problem, not the problem of a generic set of customers.

Personalized goods distribution. Customers want something special that they cannot get from the average company and that distinguishes them from the masses. It should solve their unique problem, not the problem of a generic set of customers.

![]() Personalized experience. This is perhaps the most challenging of the service types in that customers want to be wowed, pampered, and treated like VIPs. They want a memorable experience, and they are willing to pay extra for it. This is luxury service, and it is only the person’s particular experience that matters, not the experience of anyone else.

Personalized experience. This is perhaps the most challenging of the service types in that customers want to be wowed, pampered, and treated like VIPs. They want a memorable experience, and they are willing to pay extra for it. This is luxury service, and it is only the person’s particular experience that matters, not the experience of anyone else.

DOES SERVICE EXCELLENCE MATTER?

Excellent firms don’t believe in excellence—only in constant improvement and constant change.

—Tom Peters, author of The Little Big Things:

163 Ways to Pursue EXCELLENCE

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the manufacturing sector is expected to lose 549,500 jobs between 2012 and 2022, an annual rate of decline of 0.5 percent. In the same time period, service-sector jobs are expected to increase from 116.1 million to 130. 2 million. This means that by 2022 the service sector will account for more than 90 percent of the jobs that will be added to the American economy.2 As more jobs are added and the service sector grows, consumers will have an increasing range of options to choose from.

In the face of increased alternatives for customers, the question then becomes, How can service organizations keep the customers that they already have and attract—and keep—new customers? The answer is by continually improving their service. A 2013 Accenture research study found that in 2012, fifty-one percent of customers switched service providers because of poor customer service experiences, causing $1.3 trillion of revenue to be transferred between companies in the United States. Banks, cable and satellite providers, and retailers were among the most often switched services.3 For service organizations in today’s economy, customer service excellence is no longer a choice but a necessity.

Stories abound about remarkable service experiences in highly benchmarked companies like the Ritz-Carlton and Four Seasons.

![]() If you had stayed at any Ritz-Carlton in the past and had indicated a preference for certain things such as fresh fruit, feather pillows, black ink in the room’s pens, or reading material, these would all be waiting for you in your room.

If you had stayed at any Ritz-Carlton in the past and had indicated a preference for certain things such as fresh fruit, feather pillows, black ink in the room’s pens, or reading material, these would all be waiting for you in your room.

![]() A guest at the Ritz-Carlton in Boston mentioned to the doorman that he had been out fishing that day and caught a 200-pound yellow fin tuna. The guest said that the fish was in his cooler in the car and explained that he was going to have to clean it and cut it when he got home and it would help if he could have some ice for now. The assistant front desk manager took the cooler to the kitchen, where the cook supervisor cleaned the fish for the guest, breaking it down into smaller pieces. The cook supervisor went a step further by cleaning the guest’s cooler and organizing the small pieces of fish in ice for him to take home.

A guest at the Ritz-Carlton in Boston mentioned to the doorman that he had been out fishing that day and caught a 200-pound yellow fin tuna. The guest said that the fish was in his cooler in the car and explained that he was going to have to clean it and cut it when he got home and it would help if he could have some ice for now. The assistant front desk manager took the cooler to the kitchen, where the cook supervisor cleaned the fish for the guest, breaking it down into smaller pieces. The cook supervisor went a step further by cleaning the guest’s cooler and organizing the small pieces of fish in ice for him to take home.

![]() A guest at a Four Seasons hotel was walking toward his room when he saw that someone had his door open and was adjusting it. When he asked what was going on, the engineer explained, “The housekeeper servicing the room next door noticed that when your door closes, it closes more with an indeterminate gentle closing sound, which is a little bit less definitive than the ‘click’ we prefer, so she called down to engineering to have us come up and zero in on the closing mechanism.”4

A guest at a Four Seasons hotel was walking toward his room when he saw that someone had his door open and was adjusting it. When he asked what was going on, the engineer explained, “The housekeeper servicing the room next door noticed that when your door closes, it closes more with an indeterminate gentle closing sound, which is a little bit less definitive than the ‘click’ we prefer, so she called down to engineering to have us come up and zero in on the closing mechanism.”4

The stories that seem to get the most press tend to be in what we call “personalized experience.” These are direct customer experiences, usually with high-end luxury businesses that spare no expense and charge a premium for their fine facilities to make the customer experience memorable. Even for the luxury brands, the behind-the-scenes routine processes have to be fine-tuned, or the customer experience will be less than pleasant. Imagine an amazing Ritz-Carlton that has your hypoallergenic pillows waiting for you and the mangoes set out in Brazil that you once said you enjoyed in Hawaii—fantastic. Now imagine that you discover the carpet smells, the toilet does not flush properly, and your bill is incorrect. The Ritz also needs to make a similar investment in its people to ensure high-quality maintenance, high-quality room cleaning, high-quality laundry service, and on and on, to provide the reliable perfect experience customers have come to expect. While customers expect a customized special experience, there are also many elements of mass standard experience that have to be correctly done behind the scenes.

Grocery chains usually fit in our mass goods distribution cell—at the other end of the spectrum from the Ritz. This is also where Toyota would sit. Grocery stores have systems designed to bring you products that fit your needs, conveniently arranged for selection and attractively presented. However, even in the basic grocery store, there are organizations that are distinguishing themselves by their service. While Whole Foods emphasizes the healthfulness of its foods, Wegmans, the grocery chain that is the consistent leader in customer satisfaction, does not occupy a distinctive niche. It has huge stores that seem to have everything any shopper could possibly want. It also sells a variety of exotic items like rare cheeses, and produce is top quality and remarkably fresh. Throughout the store, associates go out of their way to be helpful, and customers find it an exceptional shopping and service experience.

Wegmans’s exceptional customer service has much to do with how it invests in its team members. Cashiers are barred from interacting with customers until they have completed 40 hours of training. Hundreds of staffers are sent on trips around the United States and the world to become experts in their products. The company has no mandatory retirement age and has never laid off workers. All profits are reinvested in the company or shared with employees.5

Like Toyota, each of these exceptional service companies performs at a high level over long periods of time. These companies ride through downturns in the economy, they grow revenue, they steadily make profit, and they beat their industry in profitability. Unlike some of their competitors, they save cash to ride out downturns and reinvest a good deal of their profits into the business.

For more than a decade, Dr. André de Waal of the Maastricht School of Management in the Netherlands has studied many sectors to determine what makes a high-performance organization (HPO). He has learned that HPOs have a culture characterized by the following factors:6

![]() Long-term orientation. Continuity over short-term profit, collaboration with others, good long-term relationships with all stakeholders, focus on customers.

Long-term orientation. Continuity over short-term profit, collaboration with others, good long-term relationships with all stakeholders, focus on customers.

![]() High-quality management. Decisive, action oriented, strong trust relationships, coaching, holding others responsible.

High-quality management. Decisive, action oriented, strong trust relationships, coaching, holding others responsible.

![]() Open and action-oriented management. Communicating often with employees, open to change, performance oriented.

Open and action-oriented management. Communicating often with employees, open to change, performance oriented.

![]() High-quality employees. Recruiting those who want to assume responsibility and excel, from diverse backgrounds; those who are complementary, flexible, and resilient.

High-quality employees. Recruiting those who want to assume responsibility and excel, from diverse backgrounds; those who are complementary, flexible, and resilient.

![]() Continuous improvement and innovation. A distinctive strategy; processes that are continuously improved, simplified, and coordinated; core competencies and products continuously improved; reporting important and correct information.

Continuous improvement and innovation. A distinctive strategy; processes that are continuously improved, simplified, and coordinated; core competencies and products continuously improved; reporting important and correct information.

In Waal’s study of more than 2,500 organizations throughout the world, large and small, public and private, manufacturing and services, the companies that met the five profile factors above also had financial advantages compared with other companies in the study that did not meet the profile. Specifically, compared with organizations weak on these dimensions, high-performance organizations were higher by the following percentages:

![]() Revenue growth + 10%

Revenue growth + 10%

![]() Profitability + 29%

Profitability + 29%

![]() Return on assets + 7%

Return on assets + 7%

![]() Return on equity + 17%

Return on equity + 17%

![]() Return on investment + 20%

Return on investment + 20%

![]() Return on sales + 11%

Return on sales + 11%

![]() Total shareholder return + 23%

Total shareholder return + 23%

The bottom line is that service excellence pays. And we can identify the types of leadership and organizational characteristics that lead to high performance and thus to long-term financial success. These are the characteristics of great companies like Toyota.

THE TOYOTA WAY TO SERVICE EXCELLENCE

As we consider the Toyota Way to Service Excellence, what we are thinking about is how whole systems can continuously improve the way they add value to customers. We are thinking about a management and business philosophy, not a simple tool kit. As you read this book, we will clarify and expand on what we mean by service excellence the Toyota Way. When we use the term “lean,” it broadly speaks to service excellence including the following characteristcs:

![]() The ideal is always continuous flow of value to the customer without waste.

The ideal is always continuous flow of value to the customer without waste.

![]() Continuous improvement means both small steps and breakthroughs coming from innovative thinking.

Continuous improvement means both small steps and breakthroughs coming from innovative thinking.

![]() Organizations respect people enough to invest in developing them.

Organizations respect people enough to invest in developing them.

The application of lean concepts must be tailored to the individual organization:

![]() Specific countermeasures to problems will be different for different types of service processes and service organizations.

Specific countermeasures to problems will be different for different types of service processes and service organizations.

![]() Service organizations always include both routine processes that can be standardized and nonroutine processes that require different approaches to improvement.

Service organizations always include both routine processes that can be standardized and nonroutine processes that require different approaches to improvement.

![]() In the end there are no lean solutions, but rather ways of leading that engage everyone in continuous improvement toward a vision of excellence.

In the end there are no lean solutions, but rather ways of leading that engage everyone in continuous improvement toward a vision of excellence.

KEY POINTS

WHAT IS SERVICE EXCELLENCE?

1. “Services” is a broad category of different types of organizations with different purposes:

![]() Services may be intangible and consumed at the point of sale, such as hair styling, surgery, or personal training, or may supply more tangible public needs that are stored, such as electricity or water for your home.

Services may be intangible and consumed at the point of sale, such as hair styling, surgery, or personal training, or may supply more tangible public needs that are stored, such as electricity or water for your home.

![]() Some services are knowledge intensive with a heavy human element, such as creating a piece of software, and others are more repetitive and transactional, such as getting a mortgage or underwriting an insurance policy.

Some services are knowledge intensive with a heavy human element, such as creating a piece of software, and others are more repetitive and transactional, such as getting a mortgage or underwriting an insurance policy.

![]() All manufacturing organizations include service portions, and virtually all service organizations handle physical goods in a way that is similar to manufacturing. We urge you to think about work in terms of complexity rather than whether it is manufacturing or services:

All manufacturing organizations include service portions, and virtually all service organizations handle physical goods in a way that is similar to manufacturing. We urge you to think about work in terms of complexity rather than whether it is manufacturing or services:

![]() Customized work. How routine (steps, sequence, time) is the service provided (low) versus how specific is it to the unique situation (high)?

Customized work. How routine (steps, sequence, time) is the service provided (low) versus how specific is it to the unique situation (high)?

![]() Intangibility of work. How much can we physically see the transformation process (low) versus how much do we need abstract ways to describe it (high)?

Intangibility of work. How much can we physically see the transformation process (low) versus how much do we need abstract ways to describe it (high)?

2. We introduced four different types of service organizations that become more complex as we move from mass goods distribution to personalized service experiences:

![]() Mass goods distribution (tangible—low customization). Examples: fast-food restaurant, movie on our computer, a book delivered to our house from Amazon.

Mass goods distribution (tangible—low customization). Examples: fast-food restaurant, movie on our computer, a book delivered to our house from Amazon.

![]() Standard experience delivery (intangible—low customization). Examples: routine medical checkup, routine bank transaction, group exercise class.

Standard experience delivery (intangible—low customization). Examples: routine medical checkup, routine bank transaction, group exercise class.

![]() Personalized goods distribution (tangible—higher customization). Examples: boutique clothing store making clothes to order, meal in a gourmet restaurant, customized software.

Personalized goods distribution (tangible—higher customization). Examples: boutique clothing store making clothes to order, meal in a gourmet restaurant, customized software.

![]() Personalized experience (intangible—higher customization). Examples: personal training, luxury vacations.

Personalized experience (intangible—higher customization). Examples: personal training, luxury vacations.

3. What is service excellence?

![]() Mass goods distribution. Functionality, reliability, low cost, and convenience.

Mass goods distribution. Functionality, reliability, low cost, and convenience.

![]() Standard experience. Same as for mass goods distribution but with the addition of “a human touch” and respectful treatment.

Standard experience. Same as for mass goods distribution but with the addition of “a human touch” and respectful treatment.

![]() Personalized goods distribution. Specialized products that solve customers’ problems.

Personalized goods distribution. Specialized products that solve customers’ problems.

![]() Personalized experience. Luxury: VIP treatment with over-the-top, wow service experiences.

Personalized experience. Luxury: VIP treatment with over-the-top, wow service experiences.

![]() “Good” companies offer the best service they can. Excellent companies work continuously and systematically to improve that service to satisfy customers.

“Good” companies offer the best service they can. Excellent companies work continuously and systematically to improve that service to satisfy customers.