Chapter 3

![]()

Principle 1: Philosophy of Long-Term Systems Thinking

We want organizations to be adaptive, flexible, self-renewing, resilient, learning, intelligent—attributes found only in living systems. The tension of our times is that we want our organizations to behave as living systems, but we only know how to treat them as machines.

—Margaret J. Wheatley, Finding Our Way:

Leadership for an Uncertain Time

PHILOSOPHY IS THE MORAL COMPASS OF THE ORGANIZATION

In 1992 I was codirecting the Japan Technology Management Program at the University of Michigan to study and transfer knowledge from Japan to the United States. We were obligated to share what we were learning through our research, so I organized a one-day conference for our funded researchers to present their findings. Each academic compared U.S. practices to Japan’s practices in his or her area of expertise, e.g., electronics industry, corporate strategy, supply chain management. Unbeknown to me, one of the leading TPS experts in Toyota was in the audience quietly taking everything in. At the end of the day, he introduced himself to me and said: “Interesting presentations, but you were missing the management philosophy. . . . In the future I recommend you add more discussion of philosophy.” He then graciously excused himself. At the time I was mildly offended that he did not appreciate all the great data and observations presented. Later, on reflection, I realized we had presented a hodgepodge of loosely related academic presentations and he was absolutely right. I often reflect on that simple observation about philosophy. Why is a conservative nuts-and-bolts manufacturing company so obsessed with philosophy?

Philosophy has been defined as “a system of principles for guidance in practical affairs.”1 I think of it as the moral compass of the company. What do we stand for? Why do we exist? How is our existence making the world a better place? How will we as an institution behave in the world? The Toyota Way 2001 documents are one way of formalizing the underlying philosophy of the company.

The founder, chairman, and CEO of Four Seasons, Isadore Sharp, entitled his book Four Seasons: The Story of a Business Philosophy.2 His goal was quite simply to “build the world’s best hotel company.” His conclusion was that the only path to accomplishing this was to stand out among global hotels for exceptional service through the customer’s eyes. He further observed that he needed to “get it down to the front line: clerks, bell staff, bartenders, waiters, cooks, housekeepers, and dishwashers, the lowest-paid and in most companies least-motivated people, but the ones who would make or break a five-star service reputation.” He pulled together his general managers and explained that none of them can directly affect the customer experience—they are completely dependent on their junior employees. He then gave them both the philosophy and the challenge in one statement:

That’s going to be your managerial challenge: reaching our goal of being the best, down to the bottom of the pyramid—motivating our lowest-paid people to act on their own, to see themselves not as routine functionaries, but as company facilitators creating our customer base.

As we saw in the last chapter, to put a philosophy into practice requires socializing all members until the principles become a way of thinking and acting. And it is a never-ending process. Every exceptional story that I have heard about the Four Seasons, the unbelievable service that shocks new customers, involves an encounter with frontline employees. I randomly selected a Four Seasons in London and found it rated five stars based on 614 customer reviews on TripAdvisor. Customer statements included:

![]() “Food, service, attention to detail throughout is fantastic. I must give a special mention to Veronica who served dinner with grace and enthusiasm . . . also James in concierge, top man, and to Annabell and Caroline you are stars!!!!!”

“Food, service, attention to detail throughout is fantastic. I must give a special mention to Veronica who served dinner with grace and enthusiasm . . . also James in concierge, top man, and to Annabell and Caroline you are stars!!!!!”

![]() “Everyone is very helpful but the best service is provided by the concierge staff—they are unbelievable.”

“Everyone is very helpful but the best service is provided by the concierge staff—they are unbelievable.”

![]() “The service was particularly excellent—a special mention goes to Nat, my waiter—he was brilliant!”

“The service was particularly excellent—a special mention goes to Nat, my waiter—he was brilliant!”

![]() “The staff were friendly and super-attentive to details and all had excellent name recall. It felt like I was coming home each day.”

“The staff were friendly and super-attentive to details and all had excellent name recall. It felt like I was coming home each day.”

![]() “Hotel staff is amongst the best I have encountered anywhere in the world. The arrival experience is fantastically welcoming, and we never have to wait to check-in to our room, even when an overnight flight gets in early.”

“Hotel staff is amongst the best I have encountered anywhere in the world. The arrival experience is fantastically welcoming, and we never have to wait to check-in to our room, even when an overnight flight gets in early.”

Of course, this wonderful service would mean little if the hotel did not include excellent amenities, a great location, terrific food, and things that work. The statements almost all commented on some aspect of the room, bedding, food, spa, or whatever the customer thought was important about the overall experience. Any critical comments were about something that went wrong, like food poorly prepared or the table not properly cleaned. One two-star rating cited “great environment, sad meal.” An immediate response by management promised “to spare no effort to provide a perfect visit” next time and asked to speak personally to the dissatisfied patron. I am sure something exceptional was offered to the patron.

The service experience is one part treating customers like royalty and one part making everything work flawlessly or responding immediately to a flaw in a way that corrects the situation above and beyond customer expectations. Note that this all comes out of the philosophy of engaging every staff member to become an emissary of the company. It is easy to write a policy of greeting the customer with a smile on your face, but that does not automatically put genuine smiles on the faces of frontline staff.

This is not to say that the secret to service excellence for all organizations is wildly enthusiastic staff empowered to offer goodies to customers who have a special request or complaint. Four Seasons is in the personalized experience quadrant of our model and is a high-end luxury provider. The hotel’s value proposition is to provide crazy levels of first-class service at a first-class price. Customers willing to pay for the luxury have a flawless experience—or get amply rewarded if they complain. This model would not work in the mass goods distribution quadrant, where value is often defined by a service that works flawlessly at an affordable price.

One company that lost its customer-driven philosophy and under a new CEO struggled to regain it is United Continental, a merger of United and Continental Airlines. The merger of the two companies seemed to follow the traditional route of cost reduction through “restructuring and synergies,” without building a common culture and focus on customer service. The CEO at the time of the merger talked a great game about teamwork and set as a goal to have a new joint labor contract in place by the end of 2011. When he was ousted from his position in September of 2015, there was still no contract for flight attendants and mechanics, and coincidently the company had the lowest score in the annual airline quality report. The company is in the standard experience quadrant, but that does not mean that service excellence is irrelevant. Customers have a choice.

In September 2015 Oscar Munoz made his first public appearance as the new CEO of United Airlines. He started with an apology.3 After anonymously experiencing a terrible flight on United, he said of the merged Continental and United Airlines: “This integration has been rocky. Period.” He continued: “We just have to do that public mea culpa. . . . The experience of our customers has not been what we want it to be.”

Just before taking over as CEO, he experienced a flight from Chicago, one of the hubs of United. He watched as two people were denied boarding because the flight was oversold. He sat on the tarmac, in a cramped 50-seat regional jet, going nowhere for 30 minutes because of backups at the gate. He then waited five hours for his luggage. He struck up a conversation with other passengers, baiting them about the long delays. They agreed, but to his surprise they immediately followed with, “Wasn’t that woman nice on that flight?” They were speaking of the flight attendant, Jenna. Oscar then had a revelation that Jenna was the highlight of an otherwise terrible flight. It was a watershed moment for him. “Everybody on that flight remembered that [Jenna],” Munoz said. “The process and systems and investments and all that stuff? Those are all wonderful . . . but what I’ve got to start with is people.”

Companies merge to attain financial synergies, to get additional capabilities they otherwise lack, to acquire new technologies, and for many other reasons. Way down the list, if it is there at all, is the customer. As Oscar learned, merging two bad cultures does not magically produce a positive, purposeful culture. It did not help that the company had severe labor-management strife and that some unions were working without a contract.

Recently Karyn flew United out of her home base of Chicago. This is a main hub and one that United should try to get right. Her experience:

Truly awful. Not enough seating in the waiting area. Seats broken/ripped if you can find one. Nowhere to plug my phone in. Confused boarding process. Oversold by three seats, and people asked to give up their seats until tomorrow. They are paying $500 + hotel + all meals for the day so they are losing money . . . this flight cost only $250. All service people are trying to be nice, but there’s no hope of overcoming this process mess.

Clearly the new CEO has his work cut out for him, but he has the right perspective and passion. He quickly went to work on building trust with the unions including traveling around to understand worker concerns about relations with management. Unfortunately he had a heart attack, which put him out of commission for two months, but nonetheless he appointed an acting CEO who negotiated new contracts and began to work proactively with the unions. Munoz soon returned to work and is overseeing a slow and tenuous climb to becoming at least a decent airline.

Lean leadership too often brings to mind leaders who slash costs, cut fat, and streamline the organization so it is an efficiency machine. But a real lean leader starts with the customers and the people who serve the customers. Munoz was becoming a lean leader. In lean terms he went to the gemba, that is, where the core work of the organization is done and where the customers are served. He seems to have done it by chance. He wanted to visit his daughter and happened to experience what the rest of United and Continental customers experience all too often. That was the start of what he calls his “learning tour.”

The passion for and focus on the customer is a great starting point, but there is more to lean leadership. How will United transform from a poorly operated airline with disengaged employees to one that gets everything right? A smiling face is nice, but most of us want to get to our destination without delays, in a comfortable seat, and have our luggage show up as it is supposed to.

Munoz is quoted as saying wishfully, “If I get maybe 5,000 Jennas working through this, I think I can make it work.” But that is not going to happen. What he has to do is develop a lot more than 5,000 Jennas. He needs to build a culture of people in all parts of the airline who have Jenna’s passion and commitment and the skills to improve every aspect of operations and customer service.

There is a distinctive way of thinking about the company purpose and how to build capability that separates the philosophy of excellent companies from the mediocre.

THE LIMITATIONS OF MACHINE THINKING

From an early age, we’re taught to break apart problems in order to make complex tasks and subjects easier to deal with. But this creates a bigger problem . . . we lose the ability to see the consequences of our actions, and we lose a sense of connection to a larger whole.

—Peter Senge, The Fifth Discipline

Machine thinking is characteristic of early twentieth-century industry when the owner of capital had an insurmountable competitive advantage. If you owned the factory, the means of production, the workers came piling in and the money followed. The motivation of those workers was clear. They needed money. In fact, the most direct way to motivate them was paying by the piece—produce more pieces and you get more money.

In the early twentieth century, Frederick Taylor, the father of industrial engineering, turned this into a philosophy he called “scientific management.” It had the following characteristics:

![]() Scientific work design. Engineers scientifically study the work and break it down into small pieces that are each precisely defined to be the one best way to do the job.

Scientific work design. Engineers scientifically study the work and break it down into small pieces that are each precisely defined to be the one best way to do the job.

![]() Scientific selection. Workers are scientifically selected to have the capability to do the work, often meaning physical strength (men) or dexterity (women).

Scientific selection. Workers are scientifically selected to have the capability to do the work, often meaning physical strength (men) or dexterity (women).

![]() Scientific training. Workers are trained in the one best way to do the job.

Scientific training. Workers are trained in the one best way to do the job.

![]() Scientific incentive pay. The payment scheme financially rewards workers when they produce more units, and thus it provides more profit for the owner.

Scientific incentive pay. The payment scheme financially rewards workers when they produce more units, and thus it provides more profit for the owner.

Frederick Taylor was genuine in his belief that scientific management was the key that would unlock shared prosperity for the worker and for society. The triggers for that shared prosperity were, on the one hand, brilliant engineers who did all the thinking for the enterprise and, on the other hand, self-interest that provided the most efficient route to the only thing that mattered to workers or owners—money.

Fast-forward to 1986, and Eli Goldratt seemed to make this even more explicit in his wildly successful business novel, The Goal, in which Jonah, a kind of guru, teaches a business owner how to build a successful business. Jonah repeatedly asks what the goal of the business is. The only acceptable answer—to make money. The “theory of constraints” provided the only solution needed to meet the goal. Find and break any constraints to making money. Goldratt created a business based on training “Jonahs” who were to run a computer simulation to find the constraints and become the engineers who did the thinking for the enterprise. They were carrying on the tradition of Taylor’s scientific management.

These methods and others led to what system thinkers call “reductionist thinking.” A system can most simply be defined as a set of interconnected parts. When we focus on fixing one part or one connection, to the exclusion of working on the system, we are reducing the problem to that part only. This leads to suboptimization of the system, which leads to all sorts of other ailments.

Take, for example, an organization that Karyn worked with in which a problem in one department was “solved” by eliminating the seemingly time-consuming production of a weekly report. The people in the department felt that they had done their due diligence and involved everyone who used the report in determining the solution, and so imagine their surprise when they started receiving angry phone calls and e-mails from other departments in far areas of the company asking, “What happened to my weekly report? I can’t do my work without it.” The decision makers in the department doing the problem solving didn’t set out to disrupt the work of other departments. They simply had no idea that the information contained in the report was used in so many different ways by so many different departments. They were too disconnected to even imagine who their customers were for that report.

Machine thinkers view even complex human organizations as big machines. Humans are parts of the machines—interchangeable parts. We even hear organizations described this way: “We function like a well-oiled machine.” This type of organization is the ultimate bureaucracy—each person specializing in his part performing the job the one best way as determined by experts on work design. Process improvement is also handled by experts trained in the one best methodology for improving processes, and the experts in industrial engineering or lean six sigma see their job as control, including preventing others from tampering with their perfect process designs.

It is now a well-known story that this was efficient, and even effective, in an age of little competition and relatively slow changes in technology and the market. Companies like Ford and General Motors could be the kings of the industry by owning the biggest, most modern equipment and depending on economies of scale. People could be ushered in and out of job positions with very little training, and as long as they did not mess up too badly, customers would get a car that was good enough for their relatively low expectations.

The model worked until the “Japanese invasion” in the 1970s that brought much higher quality, fuel-efficient cars from companies like Mazda and Honda and Toyota. Then it all broke loose: the auto industry began to study the Japanese management system, and the quality revolution was born. Gurus like Dr. W. Edwards Deming preached a focus on serving customers and developing the capability to design and build in quality.

Unfortunately for the Western auto companies, it did not compute. What Deming was talking about was systems thinking, which did not register to diehard machine thinkers. I recall a friend who was sent by GM to NUMMI, a joint venture of GM and Toyota, in 1984 to learn and teach the Toyota Production System and help transform GM. He came back to GM to try to teach what he had learned, and said it was like “trying to explain what Technicolor is to people who had only ever seen in black and white.” In fact, it is the black-and-white perspective that puts blinders on machine thinkers and makes it so difficult to understand the complexity of systems.

Unfortunately, what we see in modern twenty-first-century organizations is a lot of machine thinking. Bureaucracy reigns supreme. Karyn has been battling for a decade to teach Toyota Way thinking in different service organizations, but the progress is slow and there are huge obstacles to overcome. These obstacles have everything to do with machine thinking. Karyn explains:

Most of the organizations I have worked with don’t actually refer to customers in terms of living beings at all. In payroll we just called them “account 1234,” and in human resources services, the service reps would refer to them as “service requests” or “tickets.” These are inanimate, nonhuman things. In insurance, we tend to simply refer to them by the type of transactions they are: new business, renewals, or endorsements or claims. And if we don’t process the work that customers need on time, we refer to them as “out-of-service items.” If we don’t speak about—and think about—our customers as people, but simply inanimate objects, parts of the “machine,” how can we have a hope of treating them like people?

When I am coaching and I hear managers referring to something like “out-of-service items,” I will go up to them and ask, “What is the name of the customer that the work was not completed on time for?” The manager is then usually quite surprised, because it hasn’t even occurred to them that there is a real, live person involved.

In most of my experience, in service organizations, we don’t actually see the customer as part of the system, somehow, even though they are usually tied to creating the service with us. This leads to a very internal focus on improving things that are “personal preference” or that service providers find irritating, with no thought of the customer at all.

THE NEW AGE OF ORGANIZATIONS AS LIVING SYSTEMS

It was an academic specialist in social cognition who helped me understand “East versus West” differences in machine thinking compared with systems thinking. Richard Nisbett’s The Geography of Thought summarizes many experiments that compare the world views of Asians and Westerners.4 The upshot was that a variety of cognitive experiments indicated that Asians from a variety of countries were much more likely to see the connections between parts and the Westerners were more likely to see only the parts.

For example, one of Nisbett’s doctoral students wanted to test the thesis that Asians see the world as through a wide-angle lens and Americans have something more like tunnel vision. He developed a simple black-and-white graphic of fish in a sea.5 Each scene had a “focal fish” that was larger, brighter, and faster than the others. There were also rapidly moving animals and plants, rocks, and bubbles. He asked students at Kyoto University and University of Michigan what they saw. Japanese participants tended to begin by describing the environment, such as whether it looked like a pond or the ocean. The Americans were three times as likely to begin detailing the focal fish. Other studies tested recall. Japanese, compared with Americans, were much more likely to remember specific objects if they were presented in the same context in which they originally saw them. The consistent finding: Asians saw relationships and context, and Americans saw isolated items, suggesting Asians were more natural systems thinkers.

Nisbett speculated on the historical origins of these different ways of thinking. Plato and Aristotle were key actors in developing the Western world view. Aristotle, a student of Plato, emphasized defining the world in fixed categories and looking for defined relationships between those categories. In the modern vocabulary of statistics, as taught in six sigma programs, Y = f (X). That is, some dependent variable (Y), like number of defects, can be explained as some function of one or more independent variables (X), like how well employees are trained. The reasoning is that if we properly measure the variables and find the right statistical relationship, then we can accurately predict what we need to change to get the desired level on the dependent variable. Of course, it takes specially trained process improvement specialists to work this mathematical magic and find the one best way—sound familiar?

Nisbett argued that the deterministic, machine-like world view in the West can be traced back at least as far as the Greek philosophers:

Greeks were independent and engaged in verbal contention and debate in an effort to discover what people took to be the truth. They thought of themselves as individuals with distinctive properties, as units separate from others within the society, and in control of their own destinies. Similarly, Greek philosophy started from the individual object—the person, the atom, the house—as the unit of analysis and it dealt with the properties of the object. The world was in principle simple and knowable: All one had to do was to understand what an object’s distinctive attributes were so as to identify its relevant categories and then apply the pertinent rule to the categories.

The Asians, on the other hand, were influenced by a different set of philosophers such as Confucius and Buddha, along with a different set of experiences as farmers in complex growing conditions. Nisbett summarizes the contrasting world view that resulted from the different cultural influences in the Asian environment:

Chinese social life was interdependent and it was not liberty but harmony that was the watchword. . . . Similarly, the Way, and not the discovery of truth, was the goal of philosophy. Thought that gave no guidance to action was fruitless. The world was complicated, events were interrelated, and objects (and people) were connected.

Nisbett attributes the Asian proclivity toward the collective, and their views on how the world operates, to the ecology of rural living, particularly rice farming that is so central in China and Japan. He explains: “Agricultural peoples need to get along with one another—not necessarily to like one another—but to live together in a reasonably harmonious fashion. This is particularly true of rice farming . . . which requires people to cultivate land in concert with one another.” He also notes that irrigation systems require centralized control and that the Chinese and Japanese peasants lived in a complex world of social constraints.

The largest-ever cross-national survey, by Dutch social psychologist Geert Hofstede, supports the observations of Nisbett.6 Asian countries tend to rate highly on both collectivism and long-term thinking. Western countries, and particularly the United States, rate highly on individualism and short-term thinking. In fact, the United States is the only country in the world in which individualism is the most dominant cultural characteristic. This is not surprising in a country that celebrates its independence every July Fourth. Liberty and individual freedom are among the most fundamental and inalienable rights, as defined in the U.S. Constitution.

Historically, in Japan, men put the needs of the collective above their own personal interests. The company as a collective became primary, even sometimes eclipsing time with family. I recall that the Japanese who were sent over by Toyota to teach the Americans were at wit’s end trying to understand the “American idea of work-life balance.” Why would Americans want to race home to their families when there was still important work to do?

According to Confucian philosophy, as we grow and “become human,” we identify with larger collectivities from selves to family to friends in the community to the workplace to society at large. Toyota leaders were intensively committed to helping Japan become an economically strong industrial society. In fact, founder Sakichi Toyoda is considered the father of the modern Japanese industrial revolution. From the 1970s, Toyota turned its attention to a larger purpose—becoming a global company, which it has been working on ever since. The purpose of Toyota is always stated first as contributing to society, not Japanese society but global society. And all employees are considered team members contributing to this lofty ideal.

In sum, the short-term bottom-line focus of Western companies, that for decades has been world dominant, seems a better fit for the simpler world of the twentieth century but increasingly outdated in the twenty-first century. The thinking needed to thrive in the future seems more characteristic of Eastern views of holistic systems, teamwork, adaptation, and learning. A short-term focus on results actually seems to impede our ability to get the results we desire. A longer-term focus on building the capacity for innovating in the way we serve customers actually gets better results. The difference is a matter of the philosophy reflected in the organization’s culture.

SYSTEMS THINKING FOR HIGH-PERFORMANCE ORGANIZATIONS

The high-performance organization movement evolved separately from lean management. It began with the concept of sociotechnical systems. The term “sociotechnical systems” was coined by Eric Trist, Ken Bamforth, and Fred Emery at the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations in London. One of the early works to come out of this tradition, published in 1951, looked at technological changes that came with long-wall coal mining in England and how the changes altered the structure of work.7 In the long-wall method of getting coal, the work was spread over three shifts. The researchers observed that workers were isolated along this wall of coal working in a very regimented way, as if on an assembly line. The workers did a very narrow, defined task that was only a part of the job, and they could not see how it connected to a larger whole or to the customer. The researchers document the dysfunctional consequences of this form of work organization including the psychological stress and alienation that led to intentionally withholding productivity. The authors compare this method with the earlier, traditional method of going into the mine in small teams who work collaboratively, which they argued was actually a superior system from a social-psychological perspective and that modern technologies should be designed to facilitate the benefits of teamwork and self-direction:

A primary work organization of this type has the advantage of placing responsibility for the complete coal-getting task squarely on the shoulders of a single, small, face-to-face group which experiences the entire cycle of operations within the compass of its membership. For each participant the task has total significance and dynamic closure.

Sociotechnical systems theory continued to evolve with the study of actual work environments. Increasingly sophisticated steps were taken to create the social and technical conditions to support accountable teams who took responsibility for an intact unit of work. One of the early pioneers in this arena was Procter & Gamble, when in the 1970s the company began introducing the “technician system” of work. P&G made a variety of consumer products such as diapers and cosmetics that required highly automated processes. The major challenge for humans in this system was not the repetitive manual work, but rather the ability to control all the disturbances that interrupted the work flow, such as machine breakdowns. In the technician system, teams of workers were responsible for a complete automated line.

David Hanna8 was one of the P&G internal change agents introducing this new way of working based on systems thinking. By introducing this system he, and his colleagues, were repeatedly able to transform the lowest-performing plants in P&G into the highest-performing plants on measures of cost, quality, morale, and on-time delivery. David noted that there was a natural organizational life cycle for mechanistic companies. They may have started with a clear purpose and some product or service that the market demanded, but over time as they became increasingly complex and bureaucratic, they lost their purpose and began to turn inward, leading to win-lose scenarios, copying the competition, and eventually either going out of business or restructuring as a new business. He describes the process of shifting thinking from mechanistic to living systems as a way for the organization to self-renew, continuing to pursue, and even redefine, its purpose through organizational learning.

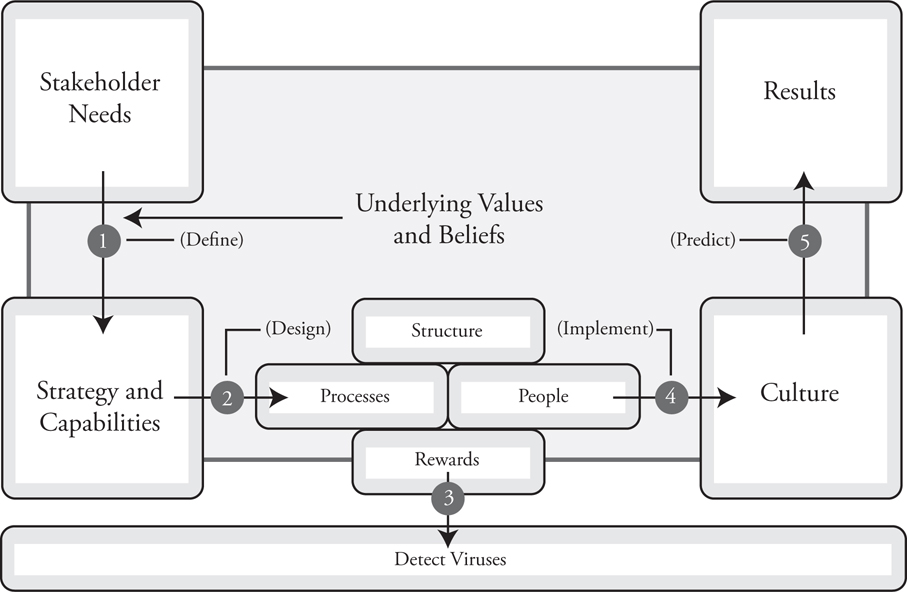

The starting point is getting the leadership team to understand the current system and its limitations and then envision a future system that would perform at a much higher level. A model used to facilitate these discussions is shown in Figure 3.1. It always begins with stakeholder analysis. Whom do we serve, and what value do we provide to each stakeholder? This leads to defining the strategy of the company to fulfill its mission and identifying the capabilities required to achieve the strategy. The internal capability includes the organizational systems and culture as defined by structure, processes, people, and rewards. Results get defined as aspirational—what is the level we need to achieve in the near term to move us closer to satisfying stakeholder needs. David’s conclusion: “You must adhere to the natural laws of living systems if you would continuously extend your organization’s life cycle.”

Figure 3.1 Organizational systems model

Source: David Hanna, The Organizational Survival Code, Hanaoka Pub., 2013

PURPOSE-DRIVEN ORGANIZATIONS

What Is Your Purpose?

Those who have been mentored by Toyota sensei (teachers) quickly get tired of the question, “What is your purpose?” It is easy to get bogged down in the details of your work, or the details of an improvement process, and lose the bigger picture. Why are you working on this project? What do you hope to accomplish and why? This is why defining the ideal state was included in Toyota Business Practices—it forces you to define the future-state direction, often called “true north” at Toyota.

Machine thinkers routinely lose sight of the bigger picture. Cause and effect are assumed to be simple and linear: “I do this because I want this outcome on that metric,” and the metric is usually financial. This myopic mindset is actually the root cause of many failed improvement programs. Tom Johnson, an accounting professor, systems thinker, and student of the Toyota Way, calls mechanistic thinking the “lean dilemma”:9

In (the mechanistic) view, financial results are a linear, additive sum of independent contributions from different parts of the business. In other words, managers believe that reducing an operation’s annual cost by $1 million simply requires them to manipulate parts of the business that generate spending in the amount of $1 million each year, say by reducing employee compensation or payments to suppliers.

Reducing spending does not improve anything. Try improving the quality of your life by reducing spending. You may reduce some stress of meeting your budget, but nothing in your life will change for the better. And cutting out something important to your health, say annual health exams, may significantly harm your life in the long term. To improve something, we have to make it better. And particularly in the complex world of service organizations that require direct interaction with customers, this almost always involves generating new ideas and changing the way people think and act to put the new processes into practice. Thus, Johnson argues that viewing organizations as living systems provides a completely different sense of purpose and is the only path to sustainable improvement:

Were managers to assume, however, that the financial performance of business operations results from a pattern of relationships among a community of interrelated parts, . . . their approach to reducing cost could be entirely different. In that case, managers might attempt to reduce costs by improving the system of relationships that determines how the business consumes resources to meet customer requirements. . . . Viewing current operations through the lens of this vision would enable everyone in the organization to see the direction that change must take to move operations closer to that vision.

As one might expect from a rogue, systems-thinking accounting professor, Johnson identifies prevailing management control systems as the leading cause of the common narrow-minded, mechanistic mindset. It causes managers to “mechanically chase financial targets” without nurturing the underlying system of relationships.

Karyn and I experience this routinely in trying to advise our clients. Even after we lead them through exercises in which they conclude that their processes are broken and their people disengaged, they still ask, “What is the return on investment of lean? Can you take me to benchmark an organization like mine that has gone lean and where I can see the results?” We want to grab them by the shoulders, stare them in the eyes, and shout, “You just mapped your value stream, you led the exercise, you saw 10 times as much waste as value added, your customers are screaming for better quality and more timely service, we identified a great future vision, and you are asking about ROI?” Clearly, shouting at somebody would be counterproductive and more likely to lead to a harassment lawsuit than a change in thinking. However, we do need to find a way to shift thinking from short-term cost reduction and immediate ROI to investing to achieve a longer-term purpose.

A purpose is more than making money. In fact, advanced lean-thinking companies like Toyota see profits as an outcome of providing superior value to customers and society, and these companies are more profitable than their competitors. Every decade Toyota gets an executive team together to develop a global vision. This is discussed intensively and refined to build consensus. Toyota Global Vision 2020 states:10

Toyota will lead the way to the future of mobility enriching lives around the world with the safest and most responsible ways of moving people. Through our commitment to quality, constant innovation and respect for the planet, we aim to exceed expectations and be rewarded with a smile. We will meet our challenging goals by engaging the talent and passion of people who believe there is always a better way.

Toyota has extended its vision beyond automobiles to “mobility.” This paves the way for the evolution of the company into new markets. For example, Toyota has done a great deal of work in advanced robotics and wishes over the long term to become a major player in the use of robots in homes and public institutions. It has robots that help move incapacitated patients in hospitals in and out of bed and robots that patients can operate by remote control to fetch things in the room. We learn that Toyota is committed to fostering innovation and respecting the planet. And the reward from customers is that they are happy with the product, as indicated by a smile. Akio Toyoda has hammered away on his company known for precision and reliability to appeal to the raw emotions of customers. The vision also tells us that Toyota will accomplish this through its people pursuing challenging goals and always searching for a better way—the spirit of the Toyota Way.

Mission Statements That Don’t Suck

In a humorous video called How to Write a Mission Statement That Doesn’t Suck,11 Dan Heath illustrates how a reasonable-sounding mission statement can become obfuscated by a well-intentioned team. In the video, team members challenge each other by wordsmithing the mission statement to broaden it and consider all possible situations. It becomes so vague and meaningless that almost anything could be done and the mission still would be fulfilled. Heath goes on to provide two useful tips for a well-written mission statement. First, use concrete language so that the purpose is so clear that anyone could identify with it. Second, talk about the “why” so it is unmistakable about what would make you care about the mission. To illustrate a well-crafted statement, Heath cites Johnson & Johnson’s famous credo: “Our first responsibility is to the doctors, nurses, and patients, mothers and fathers and all others who use our products and services.”

Contrast this to the mission statement of General Electric: “We have a relentless drive to invent things that matter: innovations that build, power, move and help cure the world. We make things that very few in the world can, but that everyone needs. This is a source of pride. To our employees and customers, it defines GE.” What did that say? What speaks to you that tells you what makes GE special?

The company Strategic Management Insight created a way to grade mission statements, and it gave the GE mission a 55 percent—a failing grade in most schools.12 Here’s why: On the plus side, the statement gives at least a vague idea of GE’s products and services and mentions employees and customers. It emphasizes innovations and the reason—“to help cure the world.” On the negative side, it is unclear what it means to “cure the world.” The company is proud, and supposedly so are the customers, of the great innovations of the company, but innovations for what purpose? What are the values of the company, and how do they serve customers?

David Hanna views a clear articulation of purpose as the starting point for developing an integrated, aligned human system.13 He points to a common gap between what the written mission statement says and what customers and employees experience on a daily basis. We all have experienced going to a restaurant or hotel or hospital and waiting endlessly, getting treated rudely, learning in frustration that there was a mistake in our order or in the information recorded in the computer, and then noticing the prominent mission statement on the wall: “Our commitment starts and ends with completely satisfying you, our customers. . . . ” What a joke!

SOUTHWEST AIRLINES’ COMPELLING MISSION: WHAT SOUTHWEST WILL AND WILL NOT DO

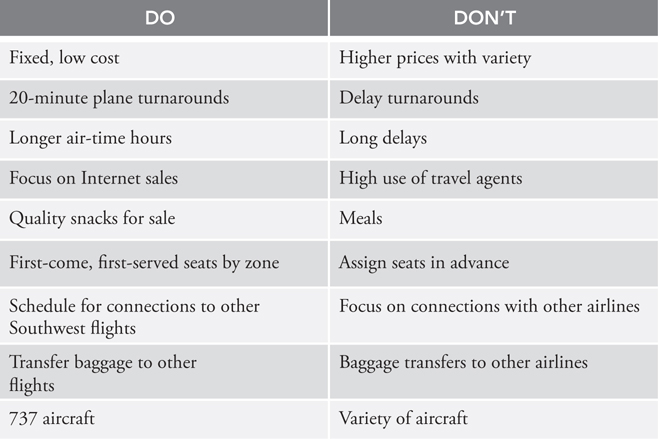

Imagine a company that knows what its customers expect and chooses to do the opposite. Ludicrous, you say! Well that is exactly what has made Southwest Airlines a stunning success in the up-and-down airline industry. Customers expected assigned seating, but at Southwest it is first-come, first-served. Customers expected free meals but got only a selection of for-purchase snacks. Customers expected their luggage to be transferred from one airline to another, but Southwest refused to participate in that process. Why would a company do such absurd things? The answer is that it defined a clear purpose that was operationalized as a strategy.

Michael Porter, the guru of corporate strategy, defined strategy as “performing activities differently than rivals do.” This requires “defining a company’s position, making trade-offs, and forging fit among activities.” He goes further in arguing that companies that focus on operational efficiency to the exclusion of strategy are playing a losing game.14 They are benchmarking and copying the activities of their competitors and simply cannibalizing each other’s profit margins.

Southwest is an example of a business in our standard experience quadrant that gets it right. The airline is, by design, not the high-priced, luxury business that we saw in Four Seasons. The company provides efficient, reliable service with a smile. Southwest has been a benchmark for its success, experiencing its first quarterly loss in 17 years in 2008, while its major competitors experienced huge swings in the business cycle including actual or near bankruptcy. Like Toyota, it immediately returned to profitability in 2009. It has dominated the limited point-to-point markets where it does business and has typically traded at about twice the price-earnings ratio of its competitors. And its safety record is at the top of the U.S. airline industry.

Southwest Airlines states as its purpose, in a simple yet eloquent way: “To connect people to what’s important in their lives through friendly, reliable, and low-cost air travel” (see the broader mission and employee commitment statement in the boxed insert). It invests heavily in its culture of friendly associates who are known to do extreme things to entertain and please customers like engaging all the customers on the plane in a singalong. In fact, Southwest is able to achieve low-price ticketing while paying among the highest wages in the industry.

To do this requires a network of interconnected and innovative activities. These include focusing only on short-haul, point-to-point routes, limited passenger service, high utilization of aircraft, and lean, productive ground and gate crews. For example, lean productive gate crews that can rapidly turn around the planes enable high aircraft utilization, and these together support low ticket prices. Lean productive gate crews also support frequent, reliable departures, and the combination of reliability and low prices is very attractive to customers.

Strategy requires trade-offs, and in fact Michael Porter says that you cannot have an effective strategy without defining what you will not do. Many companies define what they want to accomplish, but the subtext is to do anything that will earn a profit. A summary of what Southwest Airlines chooses to do and not to do is provided in Figure 3.2. Southwest will not use travel agents, serve full meals, assign seats in advance, or transfer bags to other airlines. The company uses only one model of aircraft for all of its routes, which makes it quick to turn around, and plenty of spare parts are available in case of a maintenance issue.

The activities that support Southwest’s strategic choices in turn depend on engaged, committed employees who feel more like part of a team than cheap labor. For example, it takes dedication and teamwork to rapidly turn around a plane and then become a friendly, smiling face for all your customers. Southwest employees came to view challenges as inspiring.

Figure 3.2 Southwest Airlines trade-offs to achieve its purpose

In its formative years, the company had only four planes. To afford staying in business, it had to sell one of them, so Southwest challenged its highly motivated ground crew to turn around a plane in 10 minutes when previously it was taking 45 minutes to an hour. The crew members had no idea how they were going to do it, but through a series of experiments they were able to reliably achieve a 22-minute turnaround, enough to keep the flight schedule with 25 percent fewer planes.15 In effect Southwest is living the core Toyota Way principles of respect for people and continuous improvement.

Southwest Airlines could have followed the lead of its giant competitors and simply tried to beat them on cost. It could have benchmarked best practices and imitated them. Instead Southwest chose to develop its own strategy, which made clear its distinctive purpose and positioning in the market. That included deciding what it would not do. Realizing that strategy was an evolutionary process, it engaged the entire workforce to meet challenges to its very existence. By hiring well, paying well, and developing a culture of fun and engagement, Southwest created advocates in every employee who represent the company philosophy and rally to meet each challenge.

Karyn had a recent experience with Southwest that illustrates its innovative and lean approach to customer service. We are all used to waiting in long lines in airports, and many airlines would say it is the fault of the airport that they cannot control. But Southwest does not accept that and refuses to simply copy its competitors.

I arrived at Midway airport and it was crazy—the Monday after the long July 4th weekend. I wanted to try out Southwest’s service so decided to check my bag. A Southwest employee affirmed that I had my boarding pass and then directed me to a huge line marked “Express Bag Check.” I joined the line and noticed that there was a position number above each customer service station. I prepared myself for a long wait. However, it didn’t happen. The line never stopped moving and I got to the front in about five minutes. I was shocked. At the front of the line there was a monitor that pointed to the station I should go to. I scanned my boarding pass on my phone, pressed “Check 1 bag” on the monitor, and then the friendly Southwest agent took my bag and said, “Hi Karyn! I’m sure you will enjoy your flight to Atlanta today. Your gate is B7 and your flight is on time. Anything else I can help you with, Miss Karyn?” Then off I went! I was all done in seven minutes maximum. As it turned out, our plane was 15 minutes late in arriving, but they turned the plane around so quickly that we left on time and got to our destination early.

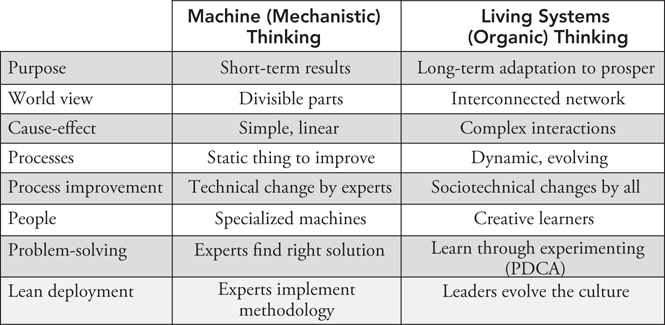

A SUMMARY OF MACHINE VERSUS SYSTEMS PHILOSOPHY

Writing down a mission statement is one thing. Making it a living reality in a stable culture is something entirely different. It involves socializing people to think and act according to core values, one person at a time. Let’s review the living systems philosophy and how it is different from the more typical machine thinking (see Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3 Organizations as machines versus living systems

The differences start with the perceived purpose of the enterprise. In the mechanistic view we want each investment, each part of the machine, to work and give us a predetermined ROI—now. Otherwise there is no point in investing.

One of the most innovative companies in the world, 3M, was nearly destroyed by a mechanistic CEO who decided to eliminate most of the new ideas in this new-product incubator, attempting to predict with statistics the most likely products to succeed. The predictions turned out to be wrong much of the time, new products declined, and the company was on a death spiral. Fortunately a systems thinker who had been with the company much of his career gained control. As a systems thinker he realized the world is full of uncertainty and it takes many promising ideas to find the one that actually works. The company eventually regained its competitive edge.

The mechanistic view sees an organization as a set of divisible parts and leads to simplistic notions of how to adapt—eliminate this, acquire that, change job descriptions, and so on. This is why organizations spend millions on computer software that will “streamline the organization” only to find the technology has little impact or even fails. This is why organizations spend millions on consultants to streamline processes only to find that once the consultants leave, the shiny, new processes implode on themselves.

Seeing the organization as a network of human and technological elements that are interrelated leads to a more complex and complete view of where we are and what needs to happen to improve the actual system. Viewing the organization this way allows us to see that “how we get there”—the means through which we fulfill our purpose and mission—is more important than simply getting to where we are going—short-term quarterly results in the mechanistic view of the organization.

With mechanistic thinking, cause and effect are direct and linear. The mechanistic manager demands to know, “Why did that happen?” The subordinate replies sheepishly, “We are not sure, sir. There are many possible causes.” The manager, getting frustrated, now issues his orders: “I do not pay you to give me excuses. I pay you for answers. There was a defect in the processing of that transaction. It happened for a reason. Find out what or who is to blame and report back to me by the end of the day what you intend to do about it.”

Let’s consider a similar situation under the leadership of a Toyota-trained teacher. Ritsuo Shingo is the son of the famous Shigeo Shingo who contributed to the creation of the Toyota Production System. Ritsuo worked his way up to the executive level in Toyota manufacturing over 40 years and retired to begin teaching and consulting. During one of his workshops, while leading delegates through a factory in Mexico, he noticed a defect in assembly as it was occurring. He immediately began observing and questioning the worker and discovered the assembly was difficult because one of the parts was out of specification. He asked where the process was that created the defect and immediately led the team back to that machine, again observing and questioning the operator. It turned out that the material purchased was out of spec. He charged off with the team in tow to the purchasing department and found out which supplier had shipped that material and asked the people in the department how they responded to a defect like this. He was set to get into a car and drive to the supplier when the workshop organizer suggested that there was not enough time in the workshop to go and the task could be left as a management assignment.

This is called the “5 why” method in Toyota’s vocabulary. Shingo kept asking why, and it drove him to understand the underlying system causes. Were he like the mechanistic-thinking manager, he would have insisted the assembler or assembly process was to blame, and the root cause would never be addressed. In fact, there may have been reason to contain the problem in assembly with a short-term countermeasure, but then the managers needed to spend time finding and addressing the root cause. A systems thinker is never satisfied with a localized bandage when the real problem has not been addressed.

Unfortunately, we see many examples of mechanistic, linear cause-and-effect thinking in complex service organization processes. Although these organizations often use multiple computer systems, have multiple people performing similar job functions (for example call centers), and create the service experience while interacting with the customer, people are in a rush to proclaim that they “know” exactly why problems happen and what can be done about them.

One organization that Karyn worked with spent quite a bit of time trying to figure out why some customers did not have health insurance benefits on the first day of employment even though they had completed the paperwork well in advance. Although the problem did not occur frequently, it certainly was a big problem for the person waiting at the doctor’s office, or even worse, needing care in the emergency room. To “solve” the problem, a “standard operating procedure” was put in place, and all customer service representatives were trained on what to do to work with the healthcare provider if they received that type of call.

Karyn later worked with a team in the organization to investigate the deeper system causes of the problem. The team found that there had been a change in timing of when information was transferred from one computer system to another. Depending on when the customer’s information was input into the first system, there was a small chance that the information would not be transferred on schedule to the second system. Once the timing of information transfer was synchronized properly, the problem was solved, and all customers had health insurance coverage on the day that they expected it.

The underlying philosophy of Plan-Do-Check-Act embraces uncertainty. We view our Plan as a hypothesis, the Do as running an experiment, the Check as an opportunity to learn, and the Act as deciding what to do next with what we have just learned. Thus we are learning through experimenting instead of predicting and controlling. We might think that the systems thinker wants to change the entire system at once, to preserve its integrity. Ironically, a lean systems thinker sees the world as too complex at the systems level to model and change in one fell swoop. She prefers to chip away at understanding through small experiments. In later chapters we will learn how this is done. At this point we are emphasizing the underlying assumptions that lead mechanistic thinkers to see processes as real things that can be molded and shaped through expert adjustment, while lean system thinkers see processes as theoretical constructs that can help guide the way people actually improve how work is done through iterative learning.

THE CHALLENGE OF CHANGING PHILOSOPHY

Philosophy is the foundation of our 4P model. It influences everything else that happens in an organization, including how to learn and improve. When senior leaders are mechanistic thinkers and are focused principally on short-term results, they will expect the implementation of measurable tools with a clear financial return on investment. Unfortunately this all too often leads to a “leaning out the enterprise mindset” of chasing easy-to-find, obvious cost-reduction opportunities—the low-hanging fruit. Hire a consultant to do this, and companies can usually save three to five times the cost of the program. Some will be one-time savings and others so-called recurring benefits year to year. The recurring benefits are suspect, as they normally depend on people following the procedures the consultants have defined—and also depend on the world remaining stagnant so the highly developed standard operating procedures do not need to change. Neither is a good assumption.

In contrast, the organic approach requires considerable up-front investment in developing people. In fact, that is the main focus in the early stages. A systems thinker might explain lean as a journey that starts with developing people:

We are beginning by investing in people doing localized projects so they can develop the skills to take on broader projects and coach more people, and we are confident we will get a multiplier effect over time in satisfying customers, increasing revenue, and decreasing cost. We cannot precisely calculate exactly what the ROI will be, or how long it will take to get it, but we are confident it will have a large and sustainable impact over time on sales and cost reduction.

In order to accomplish this, senior leaders must understand that improvement is not a “program” but a philosophy that connects their people, processes, systems, and customers together in an organic, living system.

We would like to say there is a magic elixir that will change mechanistic thinkers to systems thinkers. There is none. Moreover, we cannot change people through facts, logic, motivational speeches, or intensive classroom training programs. We cannot change the core—the heart—through trying to logically manipulate the brain. Our brains have too many defense mechanisms that attempt to justify our current way of thinking. Fundamental change in thinking is possible, but it is hard to do and takes time and repeated practice, along with repeated corrective feedback from a skilled coach. It is exactly the opposite of what a short-term-oriented mechanistic thinker wants to hear. You cannot order, buy, or quickly achieve changes in philosophy. Does that mean it is hopeless?

When I travel the world speaking about the virtues of high performance, lean organizations, and the philosophy needed to get there, most participants have mixed reactions. On the one hand, it is clear they yearn to work for an organization like I am describing, and they see a large gap between where they are and where they desire to be. On the other hand, they feel some frustration at what seems like an insurmountable barrier. They ask questions like:

![]() How do we document return on investment? “I have been trying to do what you are talking about in my department. We have gotten great results in lead-time reduction and improved customer satisfaction, but we cannot document a clear financial return. How does Toyota prove the ROI of the Toyota Way?”

How do we document return on investment? “I have been trying to do what you are talking about in my department. We have gotten great results in lead-time reduction and improved customer satisfaction, but we cannot document a clear financial return. How does Toyota prove the ROI of the Toyota Way?”

![]() How can we change senior management? “I personally believe in what you are saying, but the senior management of my company clearly does not. How can I get them to change the way they run the business?” How do we change senior people set in their ways? “What would you advise to a young professional like me who is working every day to improve how we work and the results we get, but I am going against the grain and managers have been here for decades and seem to be satisfied with the way things are.”

How can we change senior management? “I personally believe in what you are saying, but the senior management of my company clearly does not. How can I get them to change the way they run the business?” How do we change senior people set in their ways? “What would you advise to a young professional like me who is working every day to improve how we work and the results we get, but I am going against the grain and managers have been here for decades and seem to be satisfied with the way things are.”

![]() How can we find the right benchmark to visit? “We have a lean six sigma program and, just as you say, senior management does not understand it and is only looking for the financial results. So we cannot afford to invest in developing people, but are forced to chase the money. Is there a place I can bring my senior managers to see a real high-performance, lean organization in practice? We specialize in employer liability insurance—it is not like making cars—so ideally it would be a service organization like ours and not a manufacturing company.”

How can we find the right benchmark to visit? “We have a lean six sigma program and, just as you say, senior management does not understand it and is only looking for the financial results. So we cannot afford to invest in developing people, but are forced to chase the money. Is there a place I can bring my senior managers to see a real high-performance, lean organization in practice? We specialize in employer liability insurance—it is not like making cars—so ideally it would be a service organization like ours and not a manufacturing company.”

Let’s consider each of these in turn.

Proving ROI the Toyota Way

It should be clear by now that the people at Toyota do not attempt to prove that the Toyota Way is worth investing in. They believe it. It seems rather obvious to them that doing the right thing for the customer and society and developing people at all levels of the organization to continually innovate is the true path to sustainable competitiveness. They see the world as dynamic, competitive, and challenging. If the recall crisis of 2008 did anything, it reinforced this world view. Akio Toyoda’s reaction was that the company needed to strengthen the Toyota Way, not reconsider it. He preached that Toyota would redouble efforts to strengthen the basics so that it could never again be accused of endangering customers or failing to listen closely to customer concerns. One major change he has led is the movement toward regional autonomy, appointing a local CEO of major regions of the world. For example, Jim Lentz, who spent decades as a manager and then executive of Toyota Motor Sales, USA, was put in charge of Toyota of North America. Akio Toyoda took established local executives, who he believed had the Toyota Way in their DNA, and charged them with strengthening the local culture so there is one Toyota with appropriate regional flavors. Not only did Toyota go on to recover from the crisis, and then recover from the worst earthquake in the history of Japan, and then recover from the worst flooding in Thailand where many of Toyota component parts are made, but then it went on to run off a string of three years of record sales and profits—not records for Toyota but records for the entire auto industry.

Changing Senior Management Thinking

How to go about changing senior management thinking is the most difficult question I get. The question is difficult because I do not have a ready-made answer that I believe in. I have dealt with enough mechanistic-thinking C-suite executives to know that they got to where they are because they have verbal and political skills and are confident, passionate, and convincing and believe they are right. In my experience, because of the self-confidence that has gotten them to where they are and the way their success is usually judged—the bottom line—it is difficult for them to see the benefit of changing. They have been focused on the bottom line for so long—profits that can be easily calculated as revenue minus costs—that anything that will grow the business is good and anything that reduces costs is good. Remember that a mechanistic thinker looks for direct cause and effect. Acquiring a business, adding a new product line, or simply selling more will directly influence revenue. Cutting out something or someone will directly reduce cost. If you can “lean out” the business and reduce cost, you are speaking the language of most CEOs. Abstract concepts like investing in people to improve customer service simply do not compute.

The problem is that sincere professionals in the middle of the company who want to change, who want to be excited about the purpose of the company, and who are willing to work hard to remake themselves and develop their teams are stifled by the lack of support for any improvements that do not have a direct and linear relationship to ROI. They feel blocked rather than supported, and it all starts at the top with the short-term, bottom-line, mechanistic philosophy of the CEO. For the midlevel professional who is caught in this situation and wants to know what to do, I offer only one answer:

Do your best to learn and grow and make your team the best in the business. The worst that will happen is that lower performers will resent you. But in the long term you will win because you are learning and developing your team, and you will be rewarded at your current or next employer. Taking on the kingdom and attempting to transform the culture of a multinational corporation is self-defeating. Do what you can with what you’ve got. Start by changing yourself and then find ways to positively influence others, one person at a time.

The long-term possibility is that enough of the organization improves performance in measurable ways that it attracts the interest of the CEO, or at least someone in the C-suite. Even if this does not happen, the C-suite turns over, and when the new executives come in, they will have an opportunity to learn from what has been accomplished. Is there any certainty this will work? No, but it is certain that giving up will fail to change the organization.

Changing Thinking of Senior People

There is a concept called “neuroplasticity” that we will talk about in Chapter 8 on developing people. It is a fancy way of saying that we can change our brains even as we grow old. It has even been demonstrated scientifically with brain scans. Those little neurons and the pathways that connect them are actually not set in concrete. They can be strengthened, they can be weakened, and new ones can be created throughout our lives. Habits are hard to break, but they are regularly broken and replaced with new habits. As people age, it does become more difficult to develop new skills and habits, but through deliberate practice we can and do change.

If the mechanistic-thinking CEO can be difficult to change, why would we suggest that any other tenured worker is easier to change? People removed from the intense pressures of those at the very top, in our experience, are often more open to change, especially if you can convince them there is a better way that will make their jobs more pleasurable and help them to achieve their objectives. Since they are responsible for a smaller, more defined part of the organization, they can often see the direct benefits of operational excellence. Older people may have to work a bit harder at change, but when the new systems perspective is combined with the wisdom and knowledge that comes with years of experience, the result is powerful. Once older people experience working in the new way and see the positive outcomes created for their colleagues and customers, they generally enthusiastically embrace the new way of thinking and working.

Benchmarking Best-Practice Sites

I get a request like this at least every month. My reaction is generally to sigh—a combination of frustration and futility. We all enjoy being tourists and seeing interesting places. It rarely changes our life, but it can be fun and gives us something to talk about. The rationale behind visiting a lean six sigma benchmark that is similar to our place, but more advanced, is to get ideas and inspiration. We can see what we might look like if we pursue this journey. We can get specific ideas for practices that we might choose to implement. We can hear firsthand from those who have gone down this path what obstacles we might expect.

My concern is that the visits will inspire copying and reinforce mechanistic thinking. These field trips reflect a desire for certainty in what in reality is a transformation process fraught with uncertainty. We want to know. What does operational excellence look like? How did the people do it? What will we have to do? What bottom-line results should we expect? What “lean solutions” can we implement right away? The truth of complex systems is that there is no one best way and no single best practice good for all circumstances. In fact, what we need to learn is how to find our own way—how to become thinking, learning organizations.

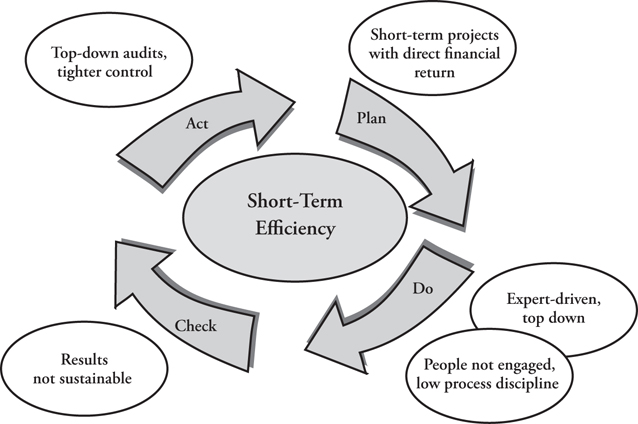

Short-Term Mechanistic Thinking Is Self-Reinforcing

In sum, it is very challenging to change those who have come to think of organizations as if they were machines to understanding organizations as living systems. Yet doing so is essential if we truly want service excellence. We must think long term. We must be willing to invest in our people and in creating an infrastructure that will indirectly lead to the passionate pursuit of satisfying customer needs. We must understand that the place where we see a problem occurring is not necessarily the place where it originated. We must understand that causation is complex and can be circular, not necessarily unidimensional and linear.

In fact, circular processes are a major barrier to changing philosophy. Vicious circles run rampant, reinforcing mechanistic thinking in the way organizations choose to improve. Mechanistic thinkers will only invest in projects with a clear financial return. This leads to experts doing all the thinking to implement their solutions. Since they cannot understand all the details of the work and since they fail to get the people who work in the process to learn and buy in, the results are not sustainable. This leads mechanistic managers to want to tighten controls even further through audits to ensure compliance, which starts the self-reinforcing loop all over again (see Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4 Vicious cycle of mechanistic improvement

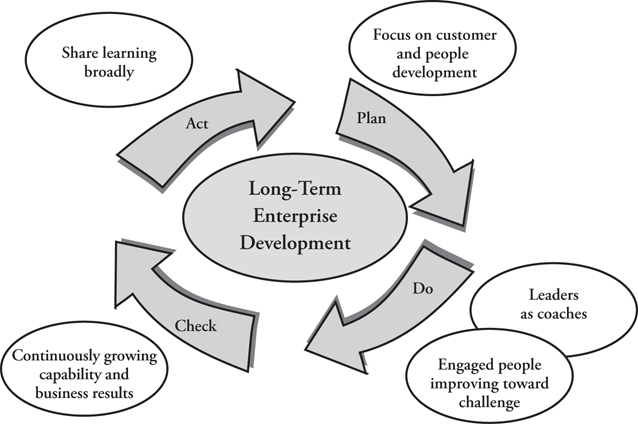

Contrast this to the virtuous cycle of an organic approach to improvement. The starting point is satisfying customers and developing our people so they will provide excellent service. This is a purpose that people can rally around. The core job of the leader is to coach and develop people who become engaged in achieving challenging objectives as a team. Suddenly the creativity of people is unleashed, and they have a personal stake in the improvements. Over the long term we continually grow our capabilities and improve our service, which leads to better sales and financial results for the business. Learning from improvements in one part of the enterprise is shared with other parts, and we become a learning enterprise (see Figure 3.5). Success reinforces the philosophy that we are building a living system, not deploying tools.

Figure 3.5 Virtuous cycle of organic improvement

PHILOSOPHY IS THE FOUNDATION

Philosophy is the foundation of service excellence—and the remaining 3Ps: process, people, and problem solving, We shift next to exploring lean processes, first through examining a fictional but realistic case study in Chapter 4 and then by exploring processes at the macrolevel and microlevel in Chapters 5 and 6. An underlying message will be to think of processes as changing and adapting, not as static and fixed. Above all else we will insist that copying “best-practice lean processes” from another organization is a bad idea. Service organizations are in fact different, and each service organization is unique and needs to follow its own path and develop and adapt its own processes guided by thinking people who work in the processes they are improving.

It is only when we aim for greatness, for the long term, that we will be willing to make deliberate investments in the long and arduous process of building a culture of service excellence. The organization’s way of thinking about the vision for success, and how the organization will get there, is philosophy. Thinking of organizations as machines to be tinkered with is necessarily limiting. All machines eventually break down and become obsolete. It is not only more successful, but even liberating to think of organizations as living systems that can self-adjust in response to feedback from the environment in order to learn, adapt, and grow.

KEY POINTS

PHILOSOPHY OF LONG-TERM SYSTEMS THINKING

1. Although philosophy is abstract, it is absolutely fundamental and the foundation for service excellence in our 4P model:

![]() Philosophy gives purpose and direction to all of an organization’s efforts.

Philosophy gives purpose and direction to all of an organization’s efforts.

2. “Mechanistic” thinking views human organizations as big machines in which people are interchangeable parts and in which cause and effect are direct and linear:

![]() This leads to suboptimizing, reductionist thinking, in which fixing one part of the organization is focused on to the exclusion and detriment of working on the whole.

This leads to suboptimizing, reductionist thinking, in which fixing one part of the organization is focused on to the exclusion and detriment of working on the whole.

![]() Companies with mechanistic thinking tend to have a short-term, results-only view (ends).

Companies with mechanistic thinking tend to have a short-term, results-only view (ends).

3. “Organic” thinking views human organizations as living systems in which all parts are interdependent and interrelated in a network of human and technological elements:

![]() A system is a set of interconnected parts with a goal of survival of the whole organism.

A system is a set of interconnected parts with a goal of survival of the whole organism.

![]() Companies with an organic philosophy are focused on finding ways to fulfill their purpose over the long term by adapting to changing customer and environmental needs by creating new products, services, and processes (means).

Companies with an organic philosophy are focused on finding ways to fulfill their purpose over the long term by adapting to changing customer and environmental needs by creating new products, services, and processes (means).

4. Systems thinking supports long-term survival and supports high-performance organizations by building the capacity for innovating in the way we serve customers throughout the organization and over time.

5. Purpose-driven organizations have strong, underlying philosophies that focus on providing superior value to customers and society and look beyond making money; making money is an outcome of fulfilling purpose.

![]() A strong, well-known, and understood purpose reduces myopia and allows everyone in the organization to keep sight of the big picture.

A strong, well-known, and understood purpose reduces myopia and allows everyone in the organization to keep sight of the big picture.

6. Changing your company’s philosophy is challenging but not impossible.

![]() A fundamental change in philosophy is hard to accomplish and takes time and repeated practice, along with repeated corrective feedback; it cannot be accomplished by copying other companies, including Toyota!

A fundamental change in philosophy is hard to accomplish and takes time and repeated practice, along with repeated corrective feedback; it cannot be accomplished by copying other companies, including Toyota!

![]() Changing from short-term mechanistic to long-term purpose-driven, organic ways of thinking and working is essential to creating a culture of service excellence.

Changing from short-term mechanistic to long-term purpose-driven, organic ways of thinking and working is essential to creating a culture of service excellence.