Chapter 2

![]()

The Toyota Way Continues to Evolve

The Toyota Way 2001 is an ideal, a standard and a guiding beacon for the people of the global Toyota organization. It expresses the beliefs and values shared by all of us.

—Fujio Cho, former Toyota president

INTRODUCTION

In the last chapter we learned that the concept of a “service organization” is more complex than it might first appear, including both routine processes that seem similar to manufacturing and complex, customized processes that defy simple recipes. We learned that the most highly rated service organizations have some common features, including a heavy emphasis on developing leaders, teamwork, and continuous improvement. We defined excellence as a process of striving to better serve each customer. The best organizations do not see excellence as an accomplishment, like something you can get an award for achieving, but rather as a continual process of striving to get better.

Now let’s return to Toyota to see how it builds the culture behind excellence. We will use as an example the Toyota Way in sales and marketing.

Toyota is the most valuable brand in the automotive industry and consistently leads the industry by almost any measure of quality, reputation, and financial performance. Perhaps because of its remarkable long-term success, the biggest fear of every Toyota president is complacency. As we saw in the Prologue, the Toyota Way philosophy driving the entire company is summarized in two pillars—respect for people and continuous improvement. Toyota leaders truly believe that if they focus intensively and continuously on these pillars, every other type of success will follow. And Toyota also knows that it is not enough to create this culture of improvement in the manufacturing portion of the company. Just as critical are those functions that would be viewed as service organizations if they were stand-alone companies: sales, marketing, purchasing, finance, accounting, strategic planning, information technology, service parts, research and development, and, of course, human resource management, for example. For Toyota, the challenge is how to drive the passion and skills to respect people and continuously improve in all areas of the business throughout an organization of over 340,000 people in sites around the world.

Over the last 40 years we have observed Toyota mature from a Japanese company with overseas branches to a global company with a common company culture that respects national differences. The Toyota Way mostly came naturally in Japan. Documenting the Toyota Way was primarily intended to develop overseas managers and team members.

In this chapter we will describe the long-term, intensive process that Toyota has used to develop a global culture of striving for excellence. It defies the quick-fix turnarounds that we all too often see associated with lean transformation, and we believe that it is a useful model that any service organization can learn from. We will then present an evolved model of the Toyota Way for services that builds on my original 4P model—philosophy, process, people, and problem solving.

DEVELOPING TOYOTA LEADERS AS COACHES: THREE WAVES

Developing people is the number one responsibility of every Toyota leader from the president to the team leader on the shop floor. The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership provides a detailed account about how Toyota leaders are developed to be coaches. By coaches we mean they are responsible for developing both the technical skills to do the work and the social and technical skills to lead improvement.

There are certainly many administrative tasks that managers must handle, such as meeting budgets, hiring, doing performance appraisals, and participating in business decisions, but for Toyota these form only the baseline of management. In fact, Volvo’s Einar Gudmundsson, introduced in Chapter 1, quickly concluded that only time at the gemba reflecting and working on improvement was value added. When they measured the amount of time his management team spent at the gemba improving the flow of work, it barely registered—less than 1 percent of the time spent. He set an immediate target of 10 hours per manager per week, which required eliminating a lot of non-value-added administrative tasks. The long-term goal was 70 percent of a manager’s time at the gemba acting as a coach to facilitate improvement.

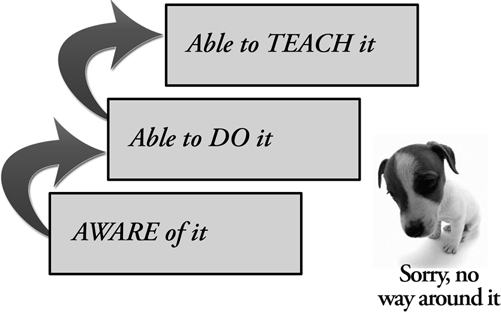

Of course, sending people to the gemba to add value is a bit like sending novices into the wilderness to learn to fend for themselves. What will they do? How will they learn? There is a definite skill set that is needed to be productive at the gemba (the place where work is done) when you are not personally doing the core work. As Mike Rother concluded in Toyota Kata, there are three steps to the process of learning any complex skill, and this led to three waves of training within Toyota (Figure 2.1): (1) aware of it—learning the principles of the Toyota Way, (2) able to do it—learning Toyota Business Practices (TBP) as the concrete method for putting the Toyota Way principles into action, and (3) able to teach it—learning On-the-Job Development (OJD) as the means of coaching learners through Toyota Business Practices.

Figure 2.1 Developing a manager as a coach of continuous improvement at the gemba

Source: Mike Rother

Wave 1: Teaching the Principles of the Toyota Way

By 2001, Toyota culture was fairly mature in most global regions. Still, unlike most companies that do not invest so deeply in developing people, every Toyota leader, even those with decades in the company, was required to go through Toyota Way training that lasted months, not days.

Like all of Toyota’s major training efforts, The Toyota Way 2001 training was developed and implemented using a similar sequence of steps:

1. The program went through intense development with pilot testing and kaizen until it was considered to be of sufficient quality to spread broadly (typically a one-year process).

2. Senior executives were trained first. Several days of classroom training were followed by a six- to eight-month period of practical application. During this period, the learners analyzed a case study requiring them to apply the principles of the Toyota Way outside the classroom. Several weeks later they reported back to discuss the case and agree on a project, which was then undertaken with a coach. At the executive level the training was intentionally cross-national to encourage global networking. Projects were undertaken locally.

3. After completing the period of practical application, the senior executives presented a report out of the project to an examining board composed of even more senior executives and subject-matter experts. Often some additional work on the project needed to be completed in order to pass.

4. After passing, the senior executives then took part in training their direct reports, including becoming part of the board of examiners as it was deployed within their organization.

5. As the training cascaded from level to level, every executive, and manager went through the same program, including classroom training, the completion of hands-on projects supervised by a coach, and the presentation of project report-outs to a board of examiners. At lower levels the scope of the projects was more limited and may only have taken three to four months to complete instead of the eight months taken by senior executives.

Deploying the Toyota Way training this way was a long-term undertaking. Working down through the organization level by level, with the people at each level becoming the mentors for those who reported to them, took about six years to complete. And as new locations are added globally and new executives are hired, there is still a need to continue the Toyota Way training.

Wave 2: Toyota Business Practices to Put the Theory into Action

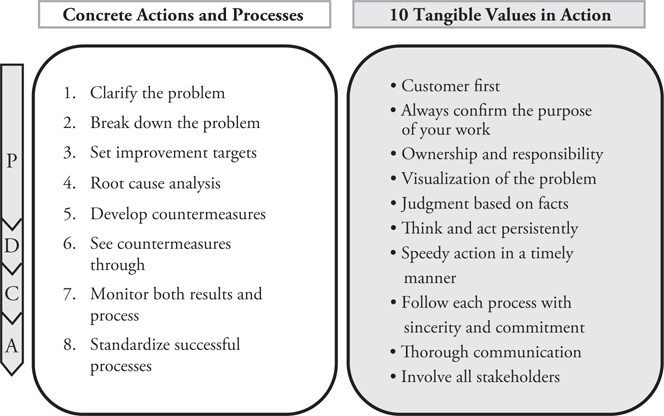

Because the Toyota Way training was designed to teach principles rather than a specific methodology, the link to action was a bit tenuous, and Fujio Cho still saw a gap in the depth of understanding he expected. It became clear that even with the application of theory through case studies and projects, there was something missing—the skill development that only comes from action. This realization resulted in the development of a second wave of training—Toyota Business Practices. Fujio Cho explained this as the “concrete method for putting the Toyota Way into action.” Many will recognize TBP as an eight-step problem-solving process (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 In Toyota Business Practices, problem solving and people development go hand in hand

Source: Toyota Motor Corporation

Notice that TBP follows the famous improvement process of Plan-Do-Check-Act, or PDCA. The development of PDCA is often attributed to Dr. Deming, who alternatively called it Plan-Do-Study-Act. The critical insight is that all “plans” are provisional and actually represent hypotheses being tested. From a scientific viewpoint the plans are theories until we test them by running experiments.1 Unfortunately, in too many organizations we see lean “experts” who presume they know what the problem is and how to solve it. This disease of certainty discourages experimenting with alternative approaches, and it truncates the opportunities for learning. The Do-Check-Act is running the experiment, checking the results, and reflecting on what has been learned.

In fact, the first five steps of TBP are all planning—establishing the hypothesis. We start with a broad definition of the problem based on identifying the ideal state and comparing it with the current state. We study the current state in detail through data and direct observation, going to and studying the gemba. We recognize that the ideal state is unachievable, so we break down the megaproblem into smaller, tractable problems that still represent major challenges, then set targets for improvement. We do our best to understand the root cause of the gap between the current state and our targets, recognizing that the root cause is our best-informed guess, and then develop a set of possible countermeasures that we believe may bring us closer to the target. The countermeasures are the hypotheses that we are directly testing by doing, then checking, and then taking further action such as standardizing what works. Let’s consider each of the steps of TBP:

1. Clarify the problem relative to the ideal (Plan). Few problem-solving efforts start with defining the ideal state. By defining the ideal state first, TBP pulls the problem solver out of the present situation and its seemingly intractable problems and focuses her on envisioning what the process could be like if it were functioning to perfection. As well as envisioning a perfect future state, in order to clarify the problem relative to the ideal, a deep understanding of the current state must be developed. And the only way to do this is by going to directly study the gemba, the place where the problems are occurring, so that the gaps between the ideal and reality become glaring.

2. Break down the problem into manageable pieces (Plan). In Step 2, the problem is broken down into challenging but achievable pieces. Although the ideal state is envisioned in Step 1, there is also an understanding that the ideal is probably unachievable. At first it may seem ridiculous to set blue-sky images of the ideal, but in reality that vision provides the direction, or true north. As the problem is broken down into smaller, attainable challenges, the path toward true north becomes clearer.

3. Set targets (Plan). In Step 3, specific targets are set. What do we expect to accomplish? These targets need to stretch beyond what seems achievable based on what is known today. Some would call these stretch targets.

4. Root cause analysis (Plan). In Step 4, the gaps that have been identified to work on are analyzed. “Why” is asked multiple times in order to get below the surface of the problem to unearth the underlying reason for the problem so that the root cause can be attacked.

5. Develop countermeasures (Plan). In Step 5, countermeasures to root causes are identified. These are not “solutions” since we do not know if they will work. They are our best guesses about what might reduce the gap between the target and the actual condition. A number of ideas are generated. Some of these ideas might come from benchmarking others who have solved similar problems, but they still remain only hypotheses until they are tested and refined in practice.

6. See countermeasures through (Do). In Step 6, the problem solver finally gets to do something. One at a time, some of the countermeasures that were generated in Step 5 are tried out in reality. This is “speedy action in a timely manner.” Note, however, that the rigor of Steps 1 to 5 ensures that the countermeasures being tested are not just shots in the dark. Testing these countermeasures is an iterative process following rapid PDCA cycles trying each idea, checking what happens, and defining further action based on what is learned.

7. Monitor both results and process (Check). Step 7 goes beyond simply checking the final score to see if the end result is what was expected. In Step 7, the problem solver is checking constantly to see whether the experiments are moving the outcome toward the target results that were set in Step 3, and the problem solver is also checking the process being used to achieve those results. In Toyota it is commonly said that achieving results without a good process is simply luck.

8. Standardize successful processes, adjust, and spread (Act). Step 8 is sometimes called “learn,” as it is the step in which the problem solver reflects and consolidates findings and determines what to do with what has been learned from the experiments. What actions will be taken next? What is working that should be standardized? What areas need further work? What should be shared with others so the organization can learn?

The training process for TBP was virtually identical to Toyota Way 2001 training—a few days of classroom training followed by the completion of a project and a presentation to a board of examiners. Again, TBP training was cascaded down from the senior executive level and this time down to the group leaders on the floor. I visited the truck plant in Princeton, Indiana, during the Great Recession when about half the workforce was not building vehicles. This was viewed as a perfect opportunity to train in many areas, including Toyota Business Practices. It was also eight years after TBP was first introduced.

Some might think that Toyota is rather slow in taking eight years to roll out a program that many companies would complete within one year or less by running three- to five-day workshops and then sending people off to do an unsupervised project. The reality is that Toyota is not slow, but serious. Fujio Cho was serious that this was the concrete method for learning the Toyota Way—learning by doing, with a coach. Any complex skill requires practice with a coach to correct deviations from the proper method. And TBP continues to be central to the company today.

In Figure 2.2, to the right of the eight steps of TBP, we see 10 tangible values in action. As each of the eight steps is being pursued, the coach is reinforcing those values. For example, in order to clarify the problem, the needs of the customers, both internal and external, must be put first. What do they want? What do they need? How do you know that? Did you go and see firsthand to understand your customers? The coach will question the learners relentlessly until they have satisfactorily understood the customers and the broader purpose of the project and until what they have learned is reflected in the problem definition. The learners do not move on to Step 2 until there is a thorough understanding of Step 1. The learners continue to deepen their knowledge as they are coached day by day.

Take, for example, Steve St. Angelo, who had earned his way to become the second American president of Toyota’s plant in Georgetown, Kentucky. As it turned out, he had a Latin American background and had run a plant in Latin America when he worked for General Motors. For his project, Steve elected to develop a long-term strategy for growing share in the Mexican market. With the help of his coach, he thoroughly explored the Mexican market to understand customers, the culture, Mexican politics, the economic environment present and forecasted, and more. He worked hard for eight months, over and above his president’s role. Ultimately the strategy that he developed in his TBP project became the basis for Toyota’s strategy for Mexico. And it seems fitting that he was selected to be the first CEO of Toyota of Latin America, allowing him to put into practice all that he had learned.

In some parts of Toyota, it is expected that immediately after every promotion, a new TPB project is completed. Not only does this continue to renew the depth of skill in improvement and the core values, but it also provides a powerful way to learn about the new job. For Toyota, problem solving is the way that the company improves to new levels of performance and develops as a learning organization.

Wave 3: On-the-Job Development to Learn How to Coach Leaders

Just as a master would teach an apprentice in the days of small craft shops, the natural way of learning in Toyota is through On-the-Job Development, or learning by being coached by a master teacher, usually your manager. However, in the past there was no handbook for the master teacher, and individual teachers developed their students in their own way. Toyota changed this by 2008.

North America was selected as the global pilot for developing OJD training. Outside of Japan, North America was the most advanced in learning the Toyota Way and could identify with others globally who were learning it for the first time. The Japanese coordinators had done remarkably well teaching the Toyota Way, but they had never had to learn about Toyota culture explicitly—all their learning was implicit as tacit knowledge passed on through daily living in the company. For this reason the United States and Canada had in some ways become better at formally teaching the Toyota Way.

The responsibility for developing the OJD training program went to Latondra Newton (now group vice president of Toyota North America), then general manager of the Team Member Development Center. The OJD program her team developed in 2007 required, as a prerequisite, TBP training. In TBP training the students learned to lead a major improvement project and had responsibility for developing team members through the process. Now OJD training would elevate this to another level, as the OJD students would be expected to coach a person leading a TBP project and the team.

Latondra’s team developed a four-step model for OJD that followed the PDCA process:

1. Pick a problem with your team (Plan). The problem is selected with the leader’s coach, the OJD student, in order to stretch the leader’s understanding of how to develop suitable work to support the company plan (we will discuss this in Chapter 9 as “hoshin kanri”).

2. Appropriately divide the work among accountable team members and make the direction compelling (Plan). The leader being coached by the OJD student then must both convey the purpose of each objective so that the work is meaningful to the team members and assign the right work to the right team members to stretch their capabilities. It is critical that the tasks and targets be carefully assigned based on each individual’s capability so they are achievable but also stretch, grow, and develop each person.

3. Execute within broad boundaries, monitor, and coach (Do and Check). This is the phase in which the leader being coached by the OJD student is actually going through the steps of TBP. The leader must constantly observe how team members are carrying out the work, understanding what issues they are dealing with. If they are not meeting expectations, the leader must be able to identify why they are not performing up to the standard and take the right countermeasures to motivate them to complete the work to standard. According to Latondra:

Maybe what is unique to Toyota’s way is there is a mindset of allowing the team members, if there is a direct line from point A to B, to waver toward the outer limits of what might be acceptable on the job such that you have coaching opportunities with them when they approach those outer limits. If they are going in the wrong direction, you allow them to go not too far off the beaten path and then use it as a teaching moment to get them back on the right track.

4. Feedback, recognition, and reflection (Act). The leader must provide a sense of achievement as the team is reaching the goal. How is each team member’s work being evaluated? How are the team members being given feedback for improvement? How is recognition of achievement being provided when the goal is achieved? The leader being trained should also be reflecting regularly with feedback from the OJD coach on what she can do better next time, thus completing the PDCA process.

The training process itself was based on experiential learning with little classroom lecturing. The first step was a web-based simulation tool that leaders completed at their own computers prior to the class. The simulation was made with actual production team members using real problems in the plants. In order to familiarize the students with the four-step model, students were given a description of the problem and a series of multiple-choice questions. On the basis of their answers, they were then shown video scenarios, acted out by team members, of what happened as a result of their choices. They would be taken down successful or unsuccessful paths and could then backtrack and try again to see what would have happened if they selected a different choice.

Next came classroom training, also based on the four steps, in which students were engaged in role-playing different scenarios and then reflecting and getting feedback. With the high level of diversity in America, it was critical for the leaders to tailor the work assignments and their approach to coaching for each individual. The classroom training included a module on emotional intelligence and emphasized understanding the background and perspective of the person being coached.

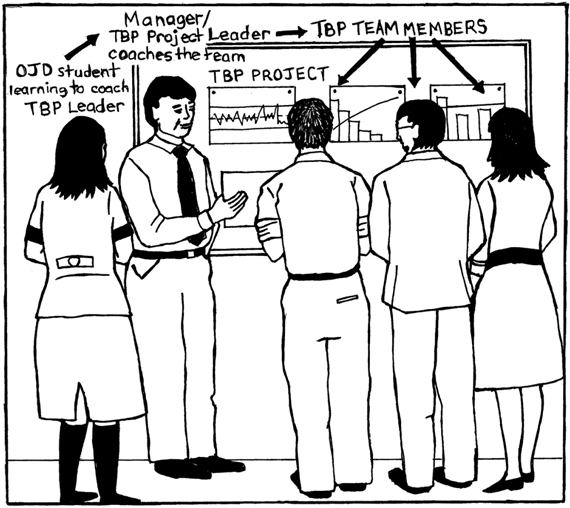

The final assignment for the individual OJD students was a project to be completed in their home plant in which they deliberately coached one person in their group through leading an improvement project using TBP. Figure 2.3 shows an OJD student learning to coach the TBP project leader. The leader being developed in OJD had to use the four steps as taught and get feedback and coaching from the supervisor (who already completed the training) and from a member of Newton’s team who was assigned to the region. The final evaluation was based on the student’s reflection, feedback from the person she coached, and input from her supervisor.

Figure 2.3 On-the-Job Development student is learning to coach the leader of a Toyota Business Practices project

OJD training in North America started in 2008. Since there were a lot of layers to coach and a broad set of functions including manufacturing, sales, engineering, and all administration to train, it was a slow process taking years. As the top leadership passed the course, they were responsible for taking over the training of the course and continuing the coaching process internally. The training was highly successful. In fact, it was so successful that it quickly began to spread to other regions, including to Japan, The training was greatly appreciated and got comments like “For the first time I really understand the Toyota Way in practice.”

THE TOYOTA WAY IN SALES AND MARKETING

For decades in Japan, Toyota Motor Sales, Inc., was a separate corporation from Toyota Motor Company, Inc. In response to antitrust regulations, these two parts of the company were separated in 1950 and the sales organization was not reunited with Toyota Motor Company, Inc., until 1982.

In the United States, prior to 2015, Toyota Motors Sales, U.S.A., Inc., continued to be a separate subsidiary with a separate location in Torrance, California. North American engineering and manufacturing team members saw the sales team members as living in an ivory tower in a pristine office complex that looked more like a university campus than a manufacturing site. Toyota executives had a vision of a unified Toyota Way culture and in 2015 began the move of both Toyota Engineering and Manufacturing and Toyota Motors Sales to a new campus in Plano, Texas.

While the Toyota Way model itself is generic, Toyota believed there was value for creating some specialized booklets and training for nonmanufacturing areas. The Toyota Way in Sales and Marketing was also introduced by Fujio Cho in 2001. Over time, other booklets were introduced for accounting, purchasing, human resource management, and other functions. Let’s consider the sales and marketing document as an example of how the Toyota Way is applied to a pure service organization.

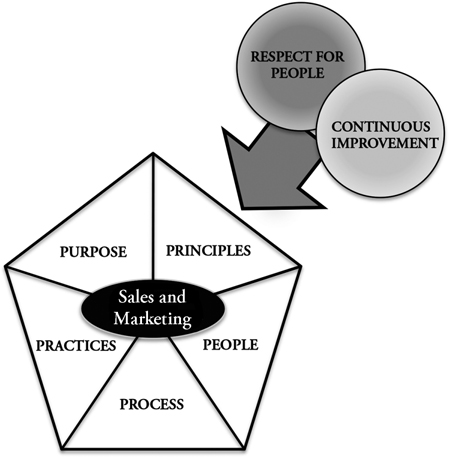

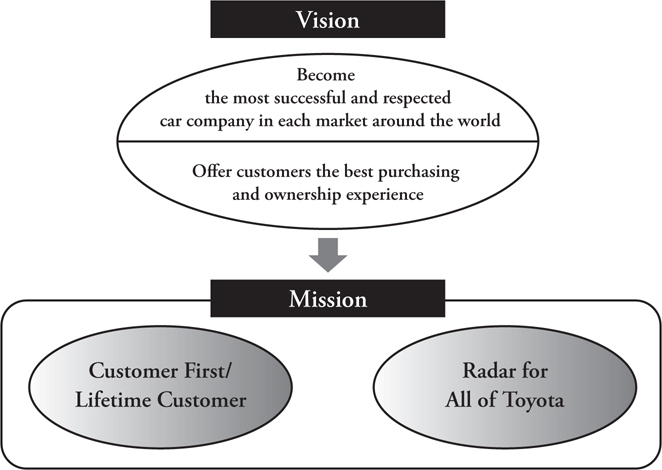

The Toyota Way in Sales and Marketing introduces a 5P model of purpose, principles, people, process, and problem solving. Although, on the surface, this may appear to be a somewhat different model, it is derived from the same general concepts of respect for people and continuous improvement (see Figure 2.4). As they are described in The Toyota Way in Sales and Marketing booklet, the 5Ps are:

Figure 2.4 The Toyota Way in Sales and Marketing 5P model

1. Purpose: Connecting to the fundamental idea of Toyota. This includes the customer is number one and better car value through the “3Cs for harmonious growth”—communication, consideration, and cooperation.

2. Principles: Connecting to the vision and mission. The vision and mission are summarized in Figure 2.5. Note that sales and marketing contribute to developing lifetime customers and act as the radar for all of Toyota: “We need to convey appropriate information to all of Toyota, including suppliers, research and development, as well as the production side. In other words, our mission is to research and understand potential customer needs.” One positive outcome of Toyota’s recall crisis of 2009 was a resurgence of the role of Toyota Motor Sales, North America, in transmitting customer needs throughout Toyota. For example, the service call center had invaluable intelligence about the customer, information that had been mostly ignored but was now in great demand as engineering and manufacturing took up the challenge of being more responsive to customers.

Figure 2.5 The Toyota Way in Sales and Marketing principles connect to the Toyota Motor Sales vision and mission

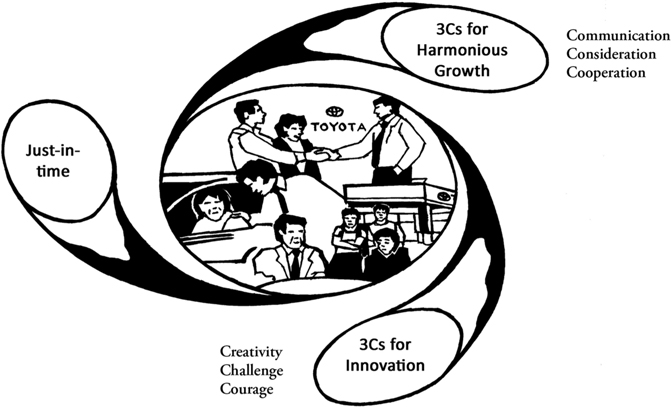

3. People: Connecting to and respecting our most important assets. Former president Eiji Toyoda is quoted in the booklet: “People are the most important asset of Toyota and the determinant of the rise and fall of Toyota.” The model for people is shown in Figure 2.6. Interestingly, the model also connects people to the Toyota Production System (TPS) concept of “just-in-time,” describing a balance between “two opposing themes of providing fast and flexible response to customers and building sales mechanisms that are efficient and waste free.” As we will see in our chapter on processes, giving customers exactly what they want, when they want it, and having efficient, stable work patterns can sometimes require trade-offs. When he first became president, Shoichiro Toyoda introduced the earlier-mentioned 3Cs for harmonious growth (communication, consideration, and cooperation) and the 3Cs for innovation—creativity, challenge, and courage, which are central to The Toyota Way 2001 values of challenge and kaizen. He gave a distinctively Toyota-like definition of the third C—courage:

Figure 2.6 The Toyota Way in Sales and Marketing people model

It is most important to take the relevant factors in all situations into careful, close consideration, and to have the courage to make clear decisions and carry them out boldly. The more uncertain the future is, the more important it is to have this courage.

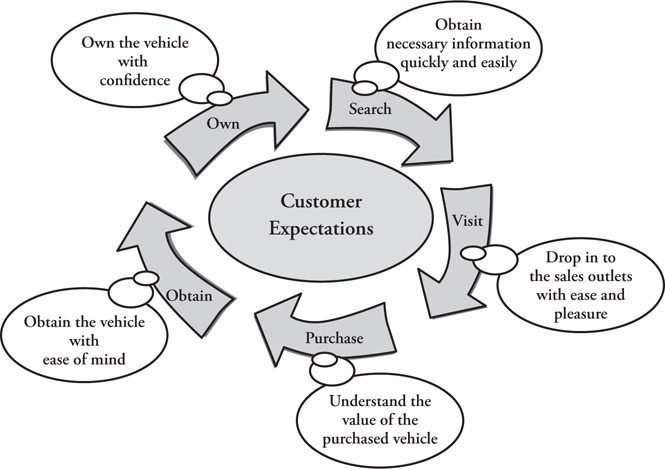

4. Process: Connecting to recommended strategies for satisfying customers. All processes in Toyota should be customer-focused, whether on an internal customer (for example, R&D is a customer of sales during product development) or on an external customer who purchases a product or service. We see the general processes that sales and marketing are responsible for, such as “obtain necessary information quickly and easily” from the customer’s viewpoint, in Figure 2.7. There is a good deal of detail below each of these steps in the booklet. For example, a way to deliver on a positive purchasing experience is through “Toyota Touch Customer Care,” which symbolizes the special feeling customers should have in any dealings with Toyota, and is defined as “Customers will experience pressure-free and pleasant purchasing. By ensuring that every customer contact is of the highest quality, we can create a Toyota advocate.”

Figure 2.7 The Toyota Way in Sales and Marketing generic processes

Toyota Touch is very dependent on the dealers, and since these are independent businesses, Toyota takes responsibility for careful selection and development of dealers. This paid off during the recall crisis when these independent businesses throughout the United States went the extra mile to take care of customers, even when the problems had nothing to do with recalled components. And the company was rewarded with over 85 percent of Toyota owners reporting, during the worst months of the negative journalistic coverage of the crisis, that they trusted Toyota, believed in the safety of their vehicles, and would recommend a Toyota to their friends.2 As well, we would expect sales and marketing processes to fit common perspectives of lean management, and this is emphasized in two regards:

![]() Supply Toyota value quickly and precisely with high quality (analogous to the TPS pillar of built-in quality).

Supply Toyota value quickly and precisely with high quality (analogous to the TPS pillar of built-in quality).

![]() Exclude muri (overburden), muda (waste), and mura (unevenness).

Exclude muri (overburden), muda (waste), and mura (unevenness).

5. Practices: Connecting to actions and measures to ensure market success. This is by far the most detailed section of the booklet, and there is a heavy emphasis on guidelines for partnership with dealers: “Set up dealer networks for pleasure, convenience, and high value and provide integrated 3S services (sales, spare parts, service), engaging in direct communication with customers to develop a long-term relationship.” I once talked to the owner of a Toyota dealership who also owned an American automaker’s dealership. The American automaker, he explained, “sent people to check on sales and push me to purchase undesirable vehicles that were not selling well. Toyota sent people to educate and inform me.” He shared with me his shelves of Toyota training materials and a monthly document Toyota prepared that detailed the local automotive market conditions.

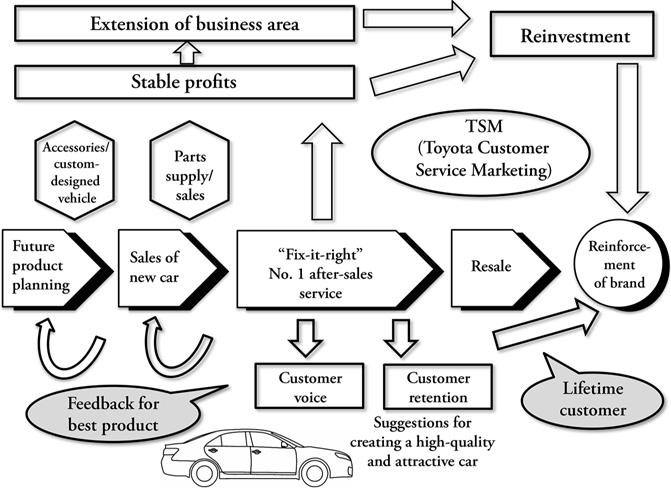

There are many models in the practices section describing guidelines for how Toyota and its dealers will work together to develop customers for life, but one comprehensive figure that ties together the intimate connections among Toyota, dealers, and customers is shown in Figure 2.8.

Figure 2.8 The Toyota Way in Sales and Marketing integrated practices

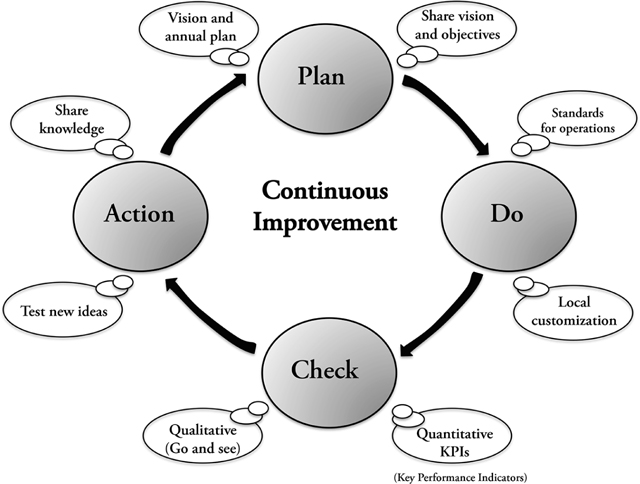

Of course, no Toyota document would be complete without an emphasis on the “continuous practice of kaizen” through the PDCA cycle (see Figure 2.9). This is communicated to the sales and marketing community in a powerful way that emphasizes the desired way of thinking—shared objectives, customization rather than the blind copying of best practices, evaluation that is both quantitative and qualitative, and shared knowledge and know-how:

Figure 2.9 The Toyota Way in Sales and Marketing PDCA model

Plan. Share our objectives through our common format and process.

Do. Develop and customize the Toyota standard for local operations.

Check. Evaluate operations from qualitative (go and see) and quantitative (key performance indicators) points of view.

Act. Share the knowledge and the know-how throughout all of Toyota and further develop our methods.

Toyota trains its dealers (independent businesses) in technical and business skills and Toyota Way thinking. For example, a consultant contracted by Toyota’s regional sales office comes to the Dunning Toyota dealership in Ann Arbor, Michigan, one day each month to help the dealership establish Toyota Express Maintenance—services like oil changes and tire rotation while you wait. The starting point was to improve the throughput and efficiency of routine maintenance through standard work, work groups, better presentation of parts and tools, visual management, and other methods. There are a series of phases to the training that can take several years for the dealer to complete. This is an intense process with strict checks by the consultant to be sure the improvements are made and sustained. The results of the transformation have been stunning, opening the eyes of the owners of the dealerships. The dealership pays for this intensive mentoring, but as long as the folks at the dealership do the work, the dealership gets reimbursed by Toyota.

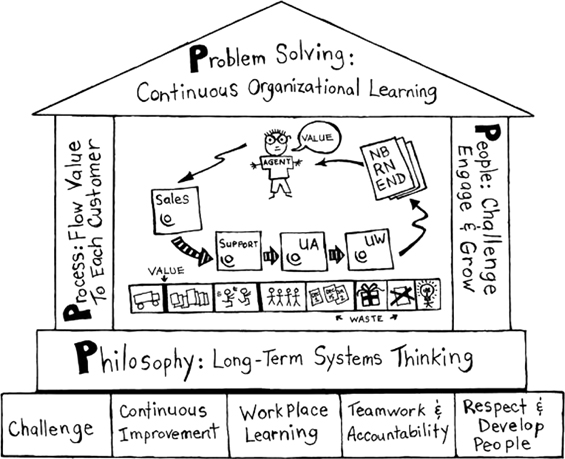

LIKER’S TOYOTA WAY 4P MODEL ADAPTED FOR SERVICE ORGANIZATIONS

In the book The Toyota Way, after studying Toyota for 20 years and carefully studying The Toyota Way 2001, I developed my own model of the underlying thinking. Karyn drew it as a house shown in Figure 2.10. The 4Ps are:

Figure 2.10 Liker’s Toyota Way 4P model

Adapted from: Jeffrey Liker, The Toyota Way, McGraw Hill: NY, 2004.

Note: The example is from insurance underwriting. UW = Underwriter; UA = Underwriting Assistant; NB = New Business; RN = Renewal

1. Philosophy. What is the purpose of our organization? In excellent companies this always goes beyond enriching owners of the business. Customers do not pay to enrich owners. What will the organization contribute to customers better than anyone else? What are the organization’s core values? What is important to the organization as a minisociety?

2. Process. The ideal process from the customer’s point of view is always one-piece flow: the customer orders exactly what he wants or needs, and it comes immediately, as it is needed, in the amount it is needed. Customers pay for value added, not for extra activities that involve people or things waiting, or work being done over because of defects, or extraneous material or information being generated. Internally, one-piece flow means continuous value-added work from step to step. There are some guidelines on the best way to accomplish this, such as working in a leveled way, without huge peaks and valleys in the workload. Technology can be important to the process, but it is not the process. The process needs to be carefully designed and then improved as conditions change and as we learn more.

3. People. Every mission statement I have ever read talks about how important people in the organization are, but the organization rarely treats people as the most valued resource. In most companies, people are “empowered” by giving them training and resources and “getting out of their way.” In the Toyota Way that is considered downright disrespectful. People need to be simultaneously challenged to stretch to new levels of performance and coached so they can learn and be successful, the essence of OJD. At Toyota, it is actively developing people, not leaving them on their own, that shows how important people are in the organization and how much they are respected.

4. Problem solving. This is a term you hear constantly within Toyota, but our usual image of what it means to solve a problem is a shell of the intended meaning. We often think of problem solving as reactive. The dam is leaking, so plug the hole. As we saw with TBP, the team member in Toyota needs to start by asking, “What is the purpose of the dam?” Answer: “A regulated flow of water.” “What would be the ideal state?” Answer: “Water flows without interruption only at the volume and speed we need.” “How can I get closer to this ideal?” And so it continues. Problem solving then becomes aspirational rather than reactive and leads to innovation rather than quick fixes. Problem solving becomes a process of learning, which, when shared appropriately, builds a learning organization.

Many have found the 4P model valuable in thinking through how to structure lean transformations. My proudest moment was in a meeting with Eiji Toyoda, the family scion who grew the company from a small Japanese automaker for the home market to a global powerhouse. On his desk he had copies of The Toyota Way in both English and Japanese. He said: “You structured our thinking so well, and explained it better then we have, and I told all of our executives to read this book because we are not as good as what you describe. We still have a long way to go to live up to your explanations.” I was glowing for months after that meeting.

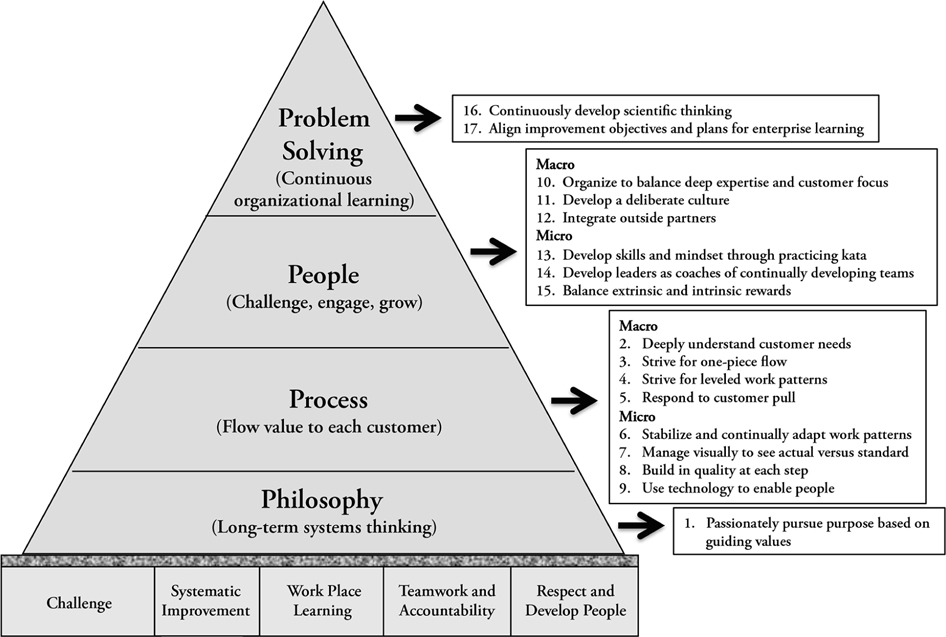

Nonetheless, in the spirit of continuous improvement, we took a look at this decade-old model, and after thinking about how it applied to services, we improved upon it (see Figure 2.11). The original model, derived from manufacturing, was a bit overweight on process and underweight in the other areas. Here is a summary of the major changes discussed in detail in the chapters for each of the 4Ps:

Figure 2.11 Toyota Way to service excellence 4P model

1. Philosophy. In The Toyota Way I emphasized that living a philosophy requires long-term thinking, even at the expense of short-term financial considerations. We still believe this is the critical starting point. Organizations that focus on the short term expect any investment they make to have an immediate return on investment (ROI), even investments in people. In addition, they tend to think of discrete improvement of independent processes rather than improving the overall system of serving customers. The Toyota Way is based on systems thinking. How can we integrate processes, people, and problem solving to add ever increasing value to our customers? What will set us apart from the competition? This will change over time. To deliver on the strategy requires adaptable people who are continually improving the processes critical for the strategy. This is where culture and values come in. While strategies and business models can change, values are the bedrock of the company and rarely change. Investing in people, culture, and capability to deliver on a well-thought-out strategy is a long-term endeavor. Organizations that account for success quarterly do not stand a chance of building true capability for service excellence.

2. Process. We have found it useful to distinguish between process improvements at the macrolevel and microlevel. At the macrolevel, we are focusing on the enterprise, where improvements have to be led by senior management. The popular tool of value-stream mapping looks at how material and information flow at the macrolevel, beginning with the current state and then developing a vision of the desired future state. Value-stream mapping considers the architecture of the value stream—a 30,000-foot view—starting with the customers and understanding what they want, how much, and when and working backward to design how key processes need to function to achieve our value-stream objectives. This leads directly to what is needed from our suppliers to keep value flowing seamlessly from suppliers through our processes to our customers.

The macroview is necessarily an abstraction—a theoretical image of what we would like to achieve. To put this vision into practice, it needs to be broken down to the microlevel. This is where detailed design is done and where we adapt as we experience daily obstacles and work to overcome them. The heavy lifting of continuous improvement happens at the microlevel by team members throughout the enterprise. They too are signing up for challenging objectives, understanding the current state, developing future state visions, and then, through daily PDCA, getting closer and closer to the vision.

3. People. We also find it useful to divide the way we manage and develop people into the macrolevel and microlevel. Too often we have found ourselves working with clients exclusively at the microlevel—focusing on small portions of value streams and individual processes. This is a more manageable way to learn the disciplined approach of daily PDCA, but we soon reach the limits of progress. In Lean Thinking, Womack and Jones3 argued that we should organize around value streams with a role they called value-stream managers. There are many organizational design options, but we believe, over the long term, it is important to think about macrolevel design of the organization and human resource systems and make regular adjustments as we learn. An example is companies that find there is too much insulated focus within vertical functional chimneys—specialists talking to each other—and not enough customer-focus across the horizontal value stream. Matrix organization, or even organization around product families, may be necessary to generate the needed customer focus.

4. Problem solving. At the microlevel we have discussed TBP as the way individual leaders approach challenging stretch objectives. These objectives need to be aligned to the company strategy. Hoshin kanri, aka policy deployment, is a system to provide that alignment. PDCA must take place at all levels and be aligned from the enterprise to organizational unit to work-group level. And the focus of improvement must be aligned with a clearly articulated business strategy.

THE TOYOTA WAY AS ONE VISION FOR PURSUING EXCELLENCE

The Toyota Way is not an enterprise model to be tuned to your organization and then rolled out. Principles are not recipes that can be installed in our organization as we would download standard software on our computer. Principles provide conceptual models but will not establish the patterns of thinking and acting needed for continuous improvement.

When Toyota executives in Japan realized they needed a standard way to develop their unique culture outside Japan, they began with the Toyota Way 2001 principles, but they quickly concluded that teaching these was insufficient. When they analyzed the core competencies required of everyone in the company, it came down to the ability to continuously improve toward challenging objectives. This led to the development of Toyota Business Practices, the standard eight-step approach to improvement (described earlier in the chapter). They then realized that they needed coaches to teach TBP and that these coaches needed to be embedded in the very organizations they were teaching. Teaching needed to be on the job and continuous. The only logical choice was to create an expectation that all managers are coaches of continuous improvement, and the company developed OJD as the third phase of the program to train the managers to coach the leaders of teams striving to meet defined targets.

Underlying the Toyota Way is a mindset. It is not a mysterious mindset unique to Japanese culture. It is a universal mindset of scientific thinking. Teachers like Dr. Deming were taken seriously, and Toyota learned the benefit of the simple, yet elusive, scientific method of Plan-Do-Check-Act. The company learned the power of managing by fact. It learned that problem solving is superior to people blaming. And it learned that serving customers meant seeking to stay a step ahead of them, anticipating their needs, and then focusing on building work streams to deliver value unimpeded by stagnation of the product or service. Flowing value to each customer became a centerpiece of the company’s vision of excellence. But vision is not reality. Presidents regularly lament the danger of complacency and promise to go back to the basics of the Toyota Way. They are painfully aware that Toyota is far from perfect and pursuing excellence requires continual dedication and perseverance. It is hard work!

Any service organization can learn from this universal wisdom. Learning is not the same as imitating. We cannot imitate the specific solutions that Toyota has evolved to deliver value to its customers. Toyota does not imitate its own solutions, but each part of the company continues to evolve new and better methods. We cannot imitate the culture that Toyota has evolved and continues to evolve. We cannot imitate the specific policies and procedures. Rather we can look below the surface and learn from Toyota’s way of thinking:

1. The never-ending journey of striving for excellence must be embraced deeply by the top leadership of the company.

2. Every organization must evolve its own strategy, direction, and way.

3. Leaders at all levels must be trained to use the scientific method for improvement to support the direction.

4. Training must focus primarily on doing, repeatedly, with a coach to provide corrective feedback.

5. People occupying higher levels of leadership must learn first by doing themselves and then become coaches for the next level down.

6. A sustainable chain of coaching must be established, and the chain will be as strong as the weakest link.

7. When a chain of capable managers as coaches is developed, it is then possible to develop aligned targets for improvement and expect innovative approaches to meet these targets at all levels.

8. Managers must become role models for daily management that is focused on total customer satisfaction.

9. Deviations from standards of excellence must be treated as opportunities to learn and improve how we serve customers.

This is the only pathway we know to developing a culture focused on service excellence. It is a simple recipe in theory—and a very challenging daily struggle in practice. The struggle is not in identifying waste or coming up with solutions. The struggle is to continually challenge the organization to focus, question, and learn. Simple management practices, such as going to the gemba to deeply understand the daily reality, can become monumental challenges when managers have established patterns of going everyplace else but where the work is being done. In the remainder of the book we will work our way through the 4P service excellence model in greater detail. We will continually emphasize that conceptual understanding is not the same as acting, and it is only through repeated action that we truly learn.

KEY POINTS

THE TOYOTA WAY CONTINUES TO EVOLVE

1. The Toyota Way philosophy of respect for people and continuous improvement applies just as well to services as it does to manufacturing.

2. Turning philosophy and theory into deep understanding requires practice through doing. Toyota spread the Toyota Way, starting with senior leaders, in three waves:

![]() Teaching the theory of the Toyota Way

Teaching the theory of the Toyota Way

![]() Putting the principles into action through Toyota Business Practices

Putting the principles into action through Toyota Business Practices

![]() Using On-the-Job Development training to develop managers as capable coaches who teach Toyota Business Practices

Using On-the-Job Development training to develop managers as capable coaches who teach Toyota Business Practices

3. In order to connect all areas to the vision and mission of an organization, it is important to put principles into practice throughout the enterprise; Toyota did this by spreading the Toyota Way in nonmanufacturing areas such as sales, purchasing, and R&D.

4. We have updated Liker’s original Toyota Way 4P model to address the specific needs of service organizations, balancing it more evenly across the 4 Ps:

![]() Philosophy. Delivering service excellence is a long-term philosophy, not a strategy focusing only on short-term financial rewards:

Philosophy. Delivering service excellence is a long-term philosophy, not a strategy focusing only on short-term financial rewards:

![]() What is your organization’s purpose, and how will the company contribute to society through the service it delivers?

What is your organization’s purpose, and how will the company contribute to society through the service it delivers?

![]() Process. Processes at all organizational levels must be designed and continually refined to deliver the services that customers want, striving toward single-piece flow:

Process. Processes at all organizational levels must be designed and continually refined to deliver the services that customers want, striving toward single-piece flow:

![]() Macrolevel. The architecture of the entire value stream must support service excellence.

Macrolevel. The architecture of the entire value stream must support service excellence.

![]() Microlevel. All team members throughout the enterprise must be actively engaged in seeing gaps between the desired state and the actual state of services and then working toward closing them.

Microlevel. All team members throughout the enterprise must be actively engaged in seeing gaps between the desired state and the actual state of services and then working toward closing them.

![]() People. Respecting people in an organization means challenging them to stretch to new levels of service excellence through constant coaching, not “empowering” them through training and then “getting out of their way:”

People. Respecting people in an organization means challenging them to stretch to new levels of service excellence through constant coaching, not “empowering” them through training and then “getting out of their way:”

![]() Macrolevel. Overall organizational design must support customer-focused continuous improvement and respect for people.

Macrolevel. Overall organizational design must support customer-focused continuous improvement and respect for people.

![]() Microlevel. Process-level PDCA, with coaching, develops team member capabilities.

Microlevel. Process-level PDCA, with coaching, develops team member capabilities.

![]() Problem solving. Problem-solving efforts across the organization must be aligned to deliver service excellence:

Problem solving. Problem-solving efforts across the organization must be aligned to deliver service excellence:

![]() Macrolevel. Objectives are aligned to company strategy through a clearly articulated, long-term business strategy (hoshin kanri).

Macrolevel. Objectives are aligned to company strategy through a clearly articulated, long-term business strategy (hoshin kanri).

![]() Microlevel. All improvement efforts support the delivery of service excellence as defined at the macrolevel.

Microlevel. All improvement efforts support the delivery of service excellence as defined at the macrolevel.

5. The Toyota Way principles provide conceptual models to use in thinking about our own organizations—they aren’t recipes to be copied, rolled out, installed, or implemented.

6. The idea is to deliberately build your company’s culture to focus on actively improving value for each customer.