CHAPTER 3

The meaning of NO

‘The art of leadership is saying no, not yes. It is very easy to say yes’

Tony Blair

Stuck?

Many people are.

If you feel trapped by your life, your job, or your circumstances, it may not be because you said ‘yes’ to the wrong things. You may well be saying yes to precisely the right things.

The problem is that you may not have the time or the energy to devote to them, because you are also saying ‘yes’ to a load of other stuff: stuff you ought to say ‘no’ to. Only when you have the courage to say ‘no’ to them will you be able to commit enough time to the things you want to focus on; the things you ought to focus on.

Only when you have the courage to say ‘no’ will wholly new possibilities emerge.

The power of ‘no’

‘No’ is an enormously powerful word, but it takes practice to get used to using it with confidence. There was a stage in your life, however, when you used it a lot. When you were a toddler, you liked to say ‘no’. All toddlers do: it’s a stage. They even seem to say ‘no’ to the things they like. Why is that?

‘No’ gives you control and what toddlers start to do is to exert control over their environment and the people in it: their carers and families. This means a constant stream of ‘no, no, no!’ Yes and no, used properly, are our ultimate control mechanisms in a social world. Toddlers are learning their power. As adults, we often forget this lesson. Childhood experiences taught your inner Gopher that it’s not OK to say ‘no’.

Noble objection

‘No’ is a difficult word for most adults to use, and the principal reason is because it sounds negative to us.

No: ‘negative answer to a question; used to express denial, refusal, disagreement.’

And who wants to appear to be negative? Most of us don’t really want to be negative, so even seeming to be negative to your colleagues, friends and family is a mortifying prospect. So, perhaps it’s better if you just grit your teeth, and say ‘yes’.

Saying ‘yes’

Saying ‘yes’ is a strategy that may have served you well in the past. You started your career by being good at saying ‘yes’, by delivering on your promises, and by building a reputation for being someone people could go to, to get things done. ‘Yes’ worked for you: it was a good ally.

‘Conscientious people will always take responsibility for the commitments that they make.’

The problem is this: as you move through your career and your life, there are more and more things to say ‘yes’ to. Eventually you start to reach a point where you simply cannot manage all of them. To avoid disappointing others, you start to fail on the commitments you make to yourself: your priorities start to slip.

‘Self-control means only making commitments that you are able to honour.’

If you believe that your future success is linked to saying ‘yes’ to everything, you’re in trouble. Early in your career, it may be that people respected you for being good at ‘yes’. But at some stage, this will not be enough to earn you respect. Instead, it will do little more than make you a doormat: someone people go to because they know you will say ‘yes’, without thinking.

You may fear that saying ‘no’ will alienate them. So you continue to say ‘yes’ to keep their friendship and respect. It won’t work. You may keep their friendship, but you will not maintain their respect.

Only when you learn to say ‘no’ properly can you regain people’s respect. And if you do it properly, you can maintain and enhance their friendship too. Now you will not be a doormat: instead, you will become a careful thinker who commits to the important requests and has the time to honour those commitments and deliver on them to the highest standard. You are also someone for whom life is not cluttered by busy-busy, rush-rush meaningless activities. You have become someone of substance.

Turning ‘no’ into a positive

We’ve seen that the negative connotations of ‘no’ are a barrier to feeling confident about using the word. So I want to introduce you to a radical concept: the idea that ‘no’ can be a positive word.

- Start by acknowledging the power of ‘no’, by giving it capital letters: NO.

- Now notice that NO is not a word, it is an acronym: N.O.

- N.O. stands for Noble Objection: what could be more positive than something that is ‘noble’?

N.O. (acronym): ‘Noble Objection: declining to do something for good reasons; making a positive choice to say “no”, and doing so respectfully.’

A ‘Noble Objection’ is when you choose to say ‘NO’ (for ease of use, we shall omit the full stops from here on) for reasons that you can wholly defend. It lies at the core of The Yes/No Book. Notice that it does not give you licence to say ‘no’ to your boss because you don’t like the task they give you, or to say ‘no’ to your partner, because you can’t be bothered. Neither of those is noble.

Rather, a Noble Objection is characterised by nobility: making ethical choices, and doing so with dignity. Therefore the two aspects of a Noble Objection are the following:

- What you say ‘NO’ to: Choosing to make a Noble Objection for the right reasons, being mindful of consequences to you, to others, and to your relationships with them.

- How you say ‘NO’: Making your Noble Objection in a way that lets people know that your choice is well made and leaving them feeling comfortable about your decision.

When you combine these two aspects of a Noble Objection, it becomes possible to say ‘NO’ with complete integrity.

Looking for ‘NO’s

‘Yes’ can steal your time. So, to start to understand how and when you give up your valuable time by using ‘yes’, think back over the last week. What things could you have ‘NO’d? When could you have made a Noble Objection and freed up time for something more valuable? Here is a short exercise.

- Take a sheet of paper and list the things you did last week, which you could have ‘NO’d instead. To help you, think about these questions.

- What things did you do last week that had no value for you or the person who asked you to do it?

- What things did you do last week that could equally well have been done by somebody else? (Perhaps even done better?)

- What things did you do last week that you knew you shouldn’t have taken on the moment you said ‘yes’?

- What things did you do last week that made you feel angry, bitter or resentful of the imposition?

- What things did you do last week that turned out to be a complete waste of your time?

- What things did you do last week that caused you more stress, anxiety or hassle than they were worth?

- What things did you do last week that were just to please someone, to stop them from hassling you, or because you feared they wouldn’t like you if you said ‘no’?

- What things did you do last week that stopped you doing something more important?

- How many things are there?

- Now, against each item, make a note of the approximate time you spent on each thing. Add all this up. How much time did you spend on things you could have ‘NO’d? How much time could you have freed up for other things?

- Was this a typical week?

- Now, against each of the things you said ‘yes’ to, put the name of the person to whom you said ‘yes’. Do one or two names appear time after time? Is this typical?

- What does this tell you about your relationship with that person?

- How valuable is that relationship to you?

- Is saying ‘yes’ as often as you do consistent with achieving the relationship you want with that person? (It may be.)

You can find a worksheet for this exercise at www.theyesnobook.co.uk

One simple way to help remind yourself is to make a little ‘tent card’ to put on your desk or workbench, or by your phone. You can download a template from www.theyesnobook.co.uk

YES and NO

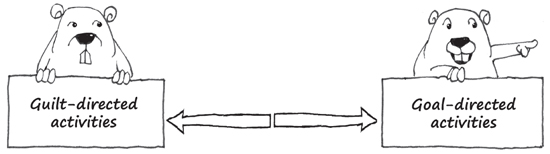

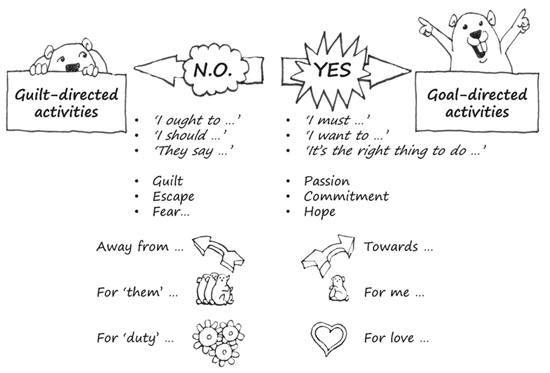

Knowing when to use your ‘NO’, and when to say a whole-hearted ‘YES’ is critical. We will look at this in great detail in Chapter 4, but here, we need to understand the underlying principle. It is time to learn about the distinction between ‘Goal-directed activities’ and ‘Guilt-directed activities’.

Goal-directed activities

Goal-directed activities are the things that you must do, you want to do, make a real difference to what you can achieve in your life, in your work, in your vocation. They are things you do because they are right and because you believe in them.

Goal-directed activities are driven by your passion and they take you towards the future you are committed to. You are drawn towards your goal-directed activities by aspiration, hope and idealism, and you do them for yourself and for the people you love.

These are the activities to say YES to. Not just a feeble ‘yes’, but a wholehearted, all-body YES signifying true commitment – because these are the activities that will contribute to your sense of fulfilment, success and happiness.

Guilt-directed activities

Guilt-directed activities are the things that you ought to do, you should do, and you feel guilty if you don’t do. They are the things that ‘they say you ought to do’ and you do them purely to please other people. Your motivations are usually duty or loyalty to people and institutions that no longer serve you well and you are driven to do them often out of fear of the consequences of not doing them.

Alternatively, guilt-directed activities are ones you do because of a guilty conscience, in atonement for some imagined or real transgression. Sometimes you do them to escape from a deeper, more important responsibility.

Guilt-directed activities are the ones to say ‘NO’ to. Make a Noble Objection to doing things out of fear, to escape responsibilities, or to assuage your guilt. These activities will bring you stress and disillusionment, and will ultimately block any sense of fulfilment and frustrate the level of material success you can achieve.

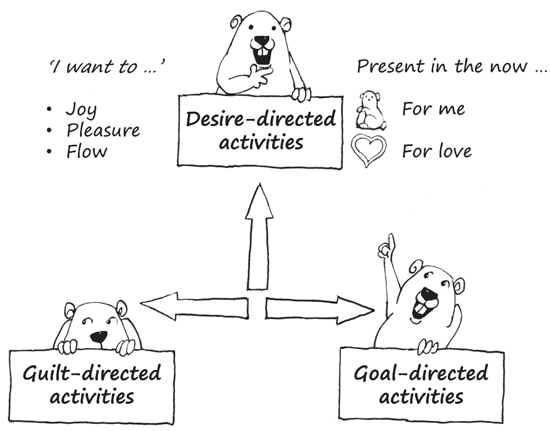

Desire-directed activities

Focusing on goal-directed activities will bring you what psychologists call ‘eudaimonic happiness’. This is the happiness, contentment and well-being we feel when we are happy with our lives. You are doing things that are true to yourself. You feel a sense of:

- autonomy: you get to make the choices about your life and how you live it

- competence: you get to do the things you are good at and enjoy

- relatedness: you get to have secure and fulfilling relationships with the people you choose

- meaning: you feel a sense of purpose and value in the things that you do

- growth: you feel that the choices you make are leading you to develop in positive ways.

But psychologists have identified another kind of happiness, which they call ‘hedonic happiness’. This is all about pleasure and joy in the moment. This is different from the happiness you will achieve through a focus on goal-directed activities, but I certainly wouldn’t want you to associate joy and pleasure with guilt. Hedonic activities are neither guilt- nor goal-directed pleasures. They take you in a new direction: the direction of pure desire.

Desire-directed activities are the things that you do to enjoy the moment. They are an immersion in the now, rather than being focused on the past (as guilt-directed activities are) or the future (as goal-directed activities are). You do them not because you must, nor because you should: you do them because you want to. You do them for yourself and you do them for love, and this makes desire-directed activities positive in the same way as goal-directed activities are.

A balanced and happy life is one where you are able to get the right mixture of goal- and desire-directed activities. You don’t use constant hedonism as an escape from reality, but you don’t abandon all opportunities to enjoy yourself, in favour of some longed-for future.

‘All work and no play make Jack or Jane miserable, dull and unfulfilled.’

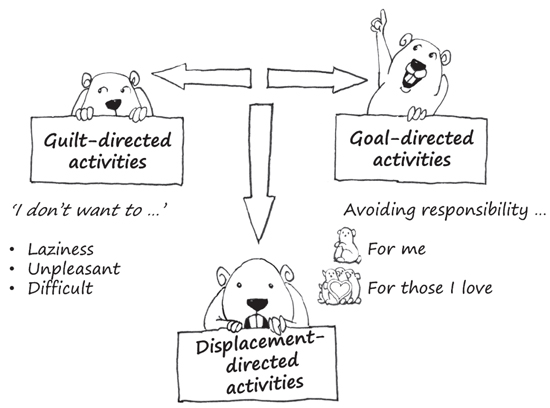

Displacement-directed activities

A final class of activities is those that you want to avoid: you are reluctant to do them despite knowing how important they are, and that they are, essentially, goal-directed. These tend to be things that seem difficult or unpleasant, so you put them off. You do something else instead: a ‘displacement activity’. This is an activity that displaces the other activity which would be a better use of your time.

You know you should say ‘YES’ but you’d rather do something more fun. So you put it off… for no better reason than ‘I don’t want to do it’ or ‘I can’t be bothered’. This is ‘purposeless procrastination’, and we’ll tackle that head-on, in Chapter 5.

Know your goals

Focusing on goal-directed activities is all very well, but it does presuppose one thing: that you know what your goals are.

Let’s start by defining ‘goals’. For our purposes, goals are what you want: they are the outcomes that will give you pride, satisfaction, pleasure…

We don’t need to define them any more clearly than that, because sometimes they will be a small thing that can be achieved quickly and easily; at other times, they may be a whole change in every aspect of your life – or of the lives of others – that could take you a lifetime to achieve. You can set material goals, spiritual goals, intellectual or creative goals. You might share the task of achieving them with others, or the responsibility may be yours alone. They may be an end in themselves, or a step along the way. All that matters is you truly want to achieve the goal.

What do you want?

The challenge, of course, is to know what you want, so that you know what to say ‘YES’ or ‘NO’ to. Start by taking a notebook or a blank sheet of paper and write down whatever comes to mind, under the heading ‘I want…’.

For some people this will be enough or will give you a very clear idea of your goals. That’s because many of us already have a pretty clear idea of what we want, and this is simply an opportunity to write it down.

THE EIGHT-PAGE METHOD

You can make the process more sophisticated by taking eight sheets of paper or eight pages in your notebook, and head them:

- What I want in twenty years’ time

- What I want in ten years’ time

- What I want in five years’ time

- What I want in two years’ time

- What I want in one year’s time

- What I want in six months’ time

- What I want in three months’ time

- What I want in one month’s time

Start with page one and put down everything you can think of. It is a long time horizon, so be ambitious for yourself.

‘It’s better to shoot for the stars and miss than to shoot for nothing and hit it.’

Then go on to page two, then three and so on, until you reach your three-month goals. You may find that you want to repeat the same goal with a shorter time scale. That’s fine; don’t worry. When you have finished, go back over everything you have written and tidy it up.

You can find a worksheet for this exercise at www.theyesnobook.co.uk.

If you are not yet satisfied with your results, then you may need a more formal process, like the four-step process, below.

Four-step process for goal setting

This process for goal setting can take anything from 24 hours to a month, and most of this time will be spent in Step 1.

Step 1: Fermenting your goals

If you haven’t thought very much about your goals before, then getting to an answer is not an instant process. You need to let your thoughts ferment, until they start to form clear ideas about what you want.

There are different ways to do this. You could combine various of these techniques.

- Relax, take your time, daydream and ponder.

- Take some long walks and clear your head, allowing thoughts to come.

- Ask yourself ‘What do I want?’ in the evening before you go to bed.

- Write:

at the top of a sheet of paper and leave it on your table before you go to bed. Set your alarm early, get up the next morning and spend half an hour at the table, writing everything that comes into your head. Do this every day for a week.

MY GOALS

Will I … - Chat about your goals and what you want with a trusted friend or partner.

- Think about all of the things that really excite and inspire you.

- Start a notebook and keep it with you. Write down ideas and goals whenever they come to you. And also write about those ideas and goals: for example, how you feel about them, what consequences they might have, and how you can make them real.

- Use the eight-page method.

Whichever of these techniques you use or combine; continue revisiting your goals from time to time, until you feel that you have some real understanding of what you want. Now it is time to write them down.

LOOKING FOR GREAT GOALS: KILLER QUESTIONS

One of the most powerful resources to help you find your goals is a question. Questions open up your thinking and the more spontaneous, unusual, disturbing they are, the more they will open your mind to new possibilities and help you to release suppressed dreams into your conscious awareness. Some questions can have that kind of impact, from time to time. I call them ‘killer questions’, and here are some of my favourites.

- What would you aim for if you had nothing to lose?

- If you learned you had only one year to live, what would you do?

- What do you really fear?

- Where did you dream you would be now when you were 16?

- Who do you look at with profound envy and think ‘I could be what they are?’

- What’s the biggest lie you have been telling yourself and others?

- If you knew you would not fail, what would you aim for?

- What else is there, beyond your current priorities?

- When you daydream and fantasise, what truth is buried there?

- If all jobs paid the same, what would you do?

- What gives you a sense of invincible energy?

- When did you last feel really happy?

- What do you most fear to hear from someone you love?

- What question would you least like to be asked?

Step 2: Upsizing your goals

Take a look at each goal that you have written down. For each one, if you can, put a measure against it. What would be a good figure to aim for? You might have a salary goal, expressed in pounds per year. Or maybe you have a lifestyle goal and you want to be able to take five weeks of foreign holidays per year. Perhaps your goal is a beautiful home – on a scale of 1 (a hovel) to 100 (a palace), where does it sit? Maybe at 60?

When you have done that, review each figure and put a second figure next to it. What would be an outrageously impressive level to aim for? Double the salary, 12 weeks’ holiday, a level 80 home. These are possible, but only with the greatest level of effort and performance from you.

So put a third figure, somewhere between the other two. Which would be a great goal to set yourself? That’s the one to go for.

Write your goals out in full now, and write each one as an IOU.

IOU Inspirational – Outrageous – Uncomfortable

- Inspirational: Make sure that each goal really grabs you by the gut and makes you want it like crazy.

- Outrageous: Set your goals to an outrageous level that will give you enormous satisfaction when you achieve them.

- Uncomfortable: Choose goals that will take you out of your comfort zone when you tackle the things that you will have to do to achieve them. If they are easy to achieve, how inspiring will they be?

Step 3: Writing yourself an IOU

The only thing you owe yourself in life is to live the best possible life that you can – to live the life you choose. Now write yourself that IOU. Summarise each IOU goal and write them all on one or more blank postcards. Carry these with you wherever you go. This IOU card will constantly inspire you by reminding you what to say ‘YES’ to, and when to say ‘NO’.

You can find a template for your IOU cards at www.theyesnobook.co.uk

Will I? How to write your IOU

Recent research* shows a surprising result. Among subjects asked to express their goals in writing, those who wrote them in the conventional way: ‘I will…’ performed less well than those who wrote them in the form: ‘Will I…?’

It seems that framing your goals as a question activates your brain more effectively. At the moment, the research has only examined short-term goal performance, but my current recommendation is that you write each of your goals in your IOU as a question or ponder:

‘Will I… ?’

* Senay, I. Albarracín, D. and Noguchi, K. (2010) ‘Motivating goal-directed behavior through introspective self-talk’, Psychological Science, 21 (4): 499–50.

Step 4: Successorising your goals

It’s now time to surround each goal with the accessories that it needs to make it realistic and achievable.

- For each goal, write down what it will mean to you to achieve it. What is really inspiring about that goal?

- Now write down how you will know for sure that your goal has been met. Give yourself an explicit completion criterion for each goal: ‘When I have achieved my goal I will know it, because… ’.

- Put together a plan.

- What are the steps along the way?

- What skills and knowledge do you need to acquire?

- Who are the people who can help you?

- What resources (things, equipment, money) do you need?

- What milestones are there along the way?

- Finally, make your goals public. Tell people about them. Don’t just pick one person and tell them everything, tell different people different goals. The more you share your goals with other people, the stronger you will find your commitment is to those goals. If you don’t feel it appropriate to share a goal, then write it down and put it in an envelope addressed to yourself, with the completion date on the envelope. Post it.

When it arrives, put it safely in a drawer, ready for you to open on the date on the envelope.

Goals in your daily life

One of the most valuable aspects of goal setting is its ability to motivate and energise you to do even the most mundane – but necessary – tasks. When you set your goals for each week or each day, then make sure that you check to see how each one supports and reinforces your bigger goals. When you do that, you will see a new meaning and purpose in what you are doing at the daily level – even if it does not, superficially, appear to be delivering you your goals.

Yes/No in an instant

Stop seeing ‘no’ as a negative. No can be positive when you say it for the right reasons and you say it well: it becomes noble – a Noble Objection. Say ‘YES’ to goal-directed activities and ‘NO’ to guilt-directed activities. Allow yourself time for the pleasures of desire-directed activities and reject the futility of displacement-directed activities.

| Yes/No: | Are you committed to making a Noble Objection to things that will truly waste your time? |

| Yes/No: | Are you ready to think carefully about when to say ‘YES’ and when to say ‘NO’? |