3

General Method of Theory Building in Applied Disciplines

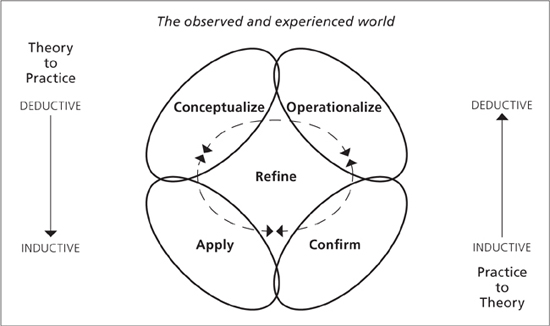

ONE OF THE CHALLENGES of theory building in applied disciplines is making the process both explicit and accessible. Although different methods of theory building advocate different theory-building research processes, there is an inherently generic nature to theory building in applied disciplines. This chapter highlights strategies used in theory building in applied disciplines and overviews the general, five-phase theory-building method mentioned earlier (Figure 3.1). This chapter specifically

This revised and edited chapter first appeared in Advances in Developing Human Resources 4(3), 221–241, S. A. Lynham, Issue Editor, and R. A. Swanson, Editor-in-Chief.

FIGURE 3.1 General Method of Theory Building In Applied Disciplines

• addresses considerations of theory building,

• discusses the establishment of a general theory-building method,

• describes the limitations of the general method, and

• examines the importance and challenges of theory building.

Believing in the need for and utility of good theory, we find the following all too familiar statement dumbfounding: “Well, that’s all very well in theory, but it doesn’t work like that in practice or in the real world.” Statements like this are rooted in a number of deeply held assumptions about the nature and utility of theory that are generally erroneous:

• that theory is disconnected and removed from practice,

• that the process of theory building happens in isolation of the real world,

• that those who engage in theory building are not the same as those who engage in practice or operate in the real world, and

• that usefulness and application is an optional outcome of theory.

What is the purpose of good theory other than to describe and explain how things actually work, and in so doing to help us improve our actions in this world? Some will contend that theory is largely idealistic (Kaplan, 1964). However, it can just as easily be argued that good theory in applied disciplines is about as realistic as it comes (Dubin, 1978; Kaplan, 1964; Van de Ven, 1989). Think about it: How many theories do you hold about the world around you and how that world works? How do these theories inform you of what works, and does not work, in day-to-day actions? Every time we encounter a new realm, we first experience it, and then we try to observe and understand how that realm presents itself and works. Next we begin to develop a system of ideas, rooted in our experience and knowledge of the world, about how to address the new realm. Then we put those ideas to the test by applying them. If these ideas work, then the issue gets satisfactorily addressed. If not, we go back to our own internal drawing boards and begin the process of problem-solution formulation and application all over again.

In effect, what we are continuously doing is developing informed knowledge frameworks about how to act on things in our world, thereby formulating ways in which to understand and address issues and problems in the world around us (Alvesson & Deetz, 2000). These knowledge and experience frameworks that we apply to our world are simply personal theories-in-use (Argyris & Schon, 1996). Think about them as theories-in-practice. Our individual lives are guided by many theories-in-practice. We put them into practice precisely because they help us to understand, explain, anticipate, know, and act in the world in better ways—to be more informed for the purpose of achieving better outcomes. Theories therefore have a very practical role in our everyday lives.

We can hold and develop grandiose theories of how the world might be and how it could work. Argyris and Schon (1996) call these idealistic, speculative conceptions of espoused theories. However, espoused and unconfirmed theories of the world and phenomena within the world have limited utility. In an applied discipline like management, theory is required to be of practical value (Kaplan, 1964; Mohrman & Lawler, 2011; Mott, 1996; Van de Ven, 1990). By virtue of its application nature, good theory is of value precisely because it fulfills one primary purpose. That purpose is to explain the meaning, nature, and functioning of a phenomenon, often experienced, but up to that point not fully understood (Campbell, 1990; Van de Ven, 1989, 2007a; Whetten, 1989).

Theory is defined as a proven explanation of a realm and how it works. It is “a coherent description, explanation and representation of observed or experienced phenomena” (Gioia & Pitre, 1990, p. 587). Theory building is the ongoing process of producing, confirming, applying, adapting, and refining theory (Lynham, 2000b). In a way, to live life successfully, we are all obliged to engage in theory building—that is, in processes by which we continuously observe, experience, think about, and understand and act in our worlds. However, these theories-in-practice are not always explicit and often occur in the form of implicit, unconscious knowledge on the part of the theorist. As such, these theories that we put into use in our daily lives are personal theories-in-practice and are seldom made explicit by the holder and user of those theories. For example, how many times has a parent or trusted friend given you advice about what works and doesn’t, about what you should or shouldn’t do about something? Yet, when questioned about what they actually know and how it all works, you get the response “I just know; trust me, I have had lots of experience with this.”

As the recipients of such personal theories-in-practice, we are faced with two choices. The first is one of a leap of faith—to apply the advice and hope that it will have the same results for you as it did for the advisor. The second is the choice of inquiry and discovery—to develop our own explanation for the issue at hand and how to deal with it. If both are pursued on only a personal front, then it is unlikely that the wisdom of either will be transmitted to anyone else. And next time we are asked the same question by someone facing a similar issue, our response is likely to mimic that of our original advisor: “I just know—trust me.” The point here is that an important function and characteristic of theory building is to make these explanations and understandings of how the world works explicit and, by so doing, to make transferable, informed knowledge for improved understanding and action in the world tacit rather than implicit.

Theory building can be further described as a “purposeful process or recurring cycle by which coherent descriptions, explanations, and representations of observed or experienced phenomena are generated, verified, and refined” (Lynham, 2000b, p. 161). Good theory building should result in two kinds of knowledge: outcome knowledge, usually in the form of explanative and predictive knowledge; and process knowledge, for example, in the form of increased understanding of how something works and what it means (Dubin, 1976). Good theory and theory building should also reflect two important qualities: rigor and relevance (Marsick, 1990a), or what have also been termed validity and utility (Van de Ven, 1989). Theory building achieves these two desired knowledge outputs and empirical qualities by use of “logic-in-use” and the “reconstructed logic” (Kaplan, 1964, p. 8). By following a logical cognitive style in the development and application of the theory, and by explicitly reconstructing, or making explicit, logic-in-use evolves.

This book presents a method—or logic-in-use—for building theory in applied disciplines. This chapter first presents basic considerations common to applied theory-building inquiry. Second, it describes applied theory building as a five-phase, general, and iterative process. Third, it briefly highlights why theory-building research is important to the applied disciplines, together with some of the challenges associated with building applied theory.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS OF THEORY BUILDING

Before reviewing the generic methodological components of theory building, let’s examine, first, two commonly used strategies in theory building and, second, the requirement of knowledge of and experience with the specific realm that is the focus of the theory-building endeavor.

Two Common Strategies

Within applied disciplines, theory-building methods must be capable of dealing with issues of application (Campbell, 1990; Lynham, 2000b; Lynham, Provo, & Ruona, 1998; Swanson, 1997, 2007; Swanson et al., 2000; Torraco, 1994, 1997, 2000). In this pursuit, it is worth considering two strategies common to theory building (Reynolds, 1971): research-to-theory and theory-to-research.

Research-to-Theory. The research-to-theory strategy, also termed the “research-then-theory strategy,” is related to “deriving the laws of nature from a careful examination of all the available data” (Reynolds, 1971, p. 140). Francis Bacon referred to the outcome of this strategy as interpretations of nature (Reynolds, 1971). As described by Reynolds, the essences of this research-to-theory strategy are as follows:

1. Select a phenomenon and list all the characteristics of the phenomenon.

2. Measure all the characteristics of the phenomenon in a variety of situations (as many as possible).

3. Analyze the resulting data carefully and determine if there are any systematic patterns among the data “worthy” of further attention.

4. Once significant patterns have been found in the data, formalization of these patterns as theoretical statements constitutes the laws of nature (axioms, in Bacon’s terminology). (p. 140)

This strategy requires two important conditions—namely, “a relatively small number of variables to measure during data collection” and “a few significant patterns to be found in the data” (Reynolds, 1971, p. 140). The dominant perspective of this theory-building strategy is a quantitative one. As a result, the corresponding assumptions about knowledge that underlie and govern the research-to-theory strategy are also of a quantitative nature. For example, the real world is objective and external to the researcher; the truth is out there to be discovered through careful, methodical, and comprehensive inquiry by the researcher; and the purpose of research is to discover universal, causal laws to enable causal explanation. Of a predominantly deductive nature, this research-to-theory strategy is thought to be well suited to the pure sciences, where the purpose of theory building is to develop large, generalizable laws of nature that explain how phenomena in the natural, objective world can be expected to work and potentially be predicted and controlled.

Theory-to-Research. The second strategy for building theory is that of theory-to-research or the “theory-then-research strategy” (Reynolds, 1971, p. 144). In this approach, theory building is made explicit through the continuous, repetitive interaction between theory construction and empirical inquiry (Kaplan, 1964; Reynolds, 1971). The essence of this theory-building strategy is as follows:

1. Develop an explicit theory in either axiomatic or process description form.

2. Select a statement generated by the theory for comparison with the results of empirical research.

3. Design a research project to ‘test’ the chosen statement’s correspondence with empirical research.

4. If the statement derived from the theory does not correspond with the research results, make appropriate changes in the theory or the research design and continue with the research.

5. If the statement from the theory corresponds with the results of the research, select further statements for testing or attempt to determine the limitations of the theory. (Reynolds, 1971, p. 144)

This theory-to-research strategy was made popular by Karl Popper, in which “he suggests that scientific knowledge would advance most rapidly through the development of new ideas [conjectures] and attempts to falsify them with empirical research [refutations]” (Reynolds, 1971, p. 144). Being of a more qualitative nature, this strategy is rooted in corresponding assumptions about the nature of scientific knowledge—for example, that there is no “real world” or “one truth” but rather that knowledge about human behavior is created in the minds of individuals; “that science is a process of inventing descriptions of phenomena” (Reynolds, 1971, p. 145); that there are multiple and divergent realities and therefore “truths”; and that the purpose of science is one of interpretive discovery and explanation of the nature and meaning of phenomena in the world (Hultgren & Coomer, 1989). Of an interactive inductive-deductive nature, this theory-to-research strategy is well suited to the applied nature of the behavioral and human sciences.

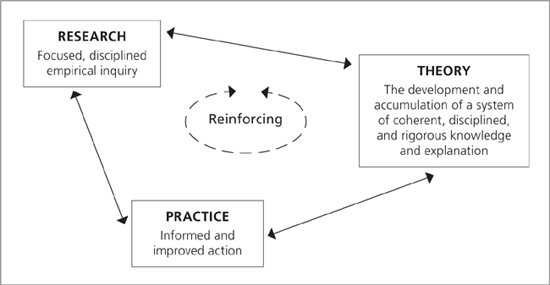

Theory-Research-Practice Cycle. The significance of these two theory-building strategies is not the need to choose one above the other. Rather, their value to the theorist is in the insight that they provide regarding the systemic nature of the interaction among three elements critical to applied theory building: (1) the development and accumulation of a system of coherent, disciplined, and rigorous knowledge and explanation (theory); (2) the conduct of focused and disciplined scholarly inquiry and discovery (research); and (3) the resulting defined and improved action that ensues from applying the outcomes of the first two elements in practice.

Rooted in systems theory, the concept of a virtuous cycle refers to a positive, reinforcing relationship of interdependence among the components of a system (Kauffman, 1980; Senge, 1990; von Bertalanffy, 1968). This growth cycle of theory-research-practice (see Figure 3.2) is fundamental to building rigorous and relevant applied theory (Dubin, 1978).

TOWARD A GENERAL THEORY-BUILDING RESEARCH METHOD

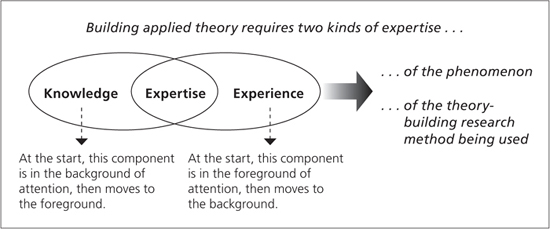

The theory-to-research theory-building strategy demands that the theorist or theory development team have expertise in both the realm central to the theory as well as in the theory-building method itself (Campbell, 1990; Cohen, 1991; Dubin, 1981; Hearn, 1958; Patterson, 1986; Swanson, 2007b). Applied theory building therefore requires the theorist to interact with and be influenced by both the phenomenon in practice and acquired knowledge within that realm. In this way, both understandings of the realm central to the theory are brought together and are ordered according to the theorist’s internal logic, or logic-in-use, and informed imagination (Cohen, 1991; Weick, 1995). This continuous interaction in applied theory building—between knowledge and experience within the realm that is the focus of the theory—facilitates the accumulation of relevant, rigorous theoretical knowledge of the phenomenon in the experienced world (see Figure 3.3).

FIGURE 3.2 Growth Cycle of Theory Building in Applied Disciplines

Figures 3.2 and 3.3 are useful in understanding the method for building theory in applied disciplines as an iterative system of five distinct phases, as we saw in Figure 3.1:

• Conceptualize,

• Operationalize,

• Apply,

• Confirm, and

• Refine.

FIGURE 3.3 Recursive Nature of Practical and Theoretical Expertise Inherent in Applied Discipline Theory Building

From an overall perspective, theory building in applied disciplines consists of two broad components: theorizing to practice and practice to theorizing. Each of these components produces distinct in-process outputs that guide applied theory-building research and ultimately result in a trustworthy, rigorous, and relevant theory for improved action (Lincoln & Denzin, 2001; Marsick, 1990a, 1990b; Van de Ven, 1989). An essential output from the theorizing component of theory building is a coherent and logical theoretical framework, which encapsulates the explanation of the realm, phenomenon, issue, or problem that is the focus of the theory. Key outputs from the practice components of theory building are carefully obtained data/findings and experiential knowledge that are used to confirm, or disconfirm, and further refine and develop the existing theory and to enhance the utility of the theory in practice. The five phases of the applied theory-building research method take place within this larger two-component frame indicated in Figure 3.1.

It is important to note again that these five phases do not necessarily need to be pursued in the order in which they appear in Figure 3.1. However, the sum of the Conceptualize, Operationalize, Apply, Confirm, and Refine phases complete the theory-building effort. Furthermore, an applied theory is never considered complete, but rather “true until shown otherwise” (Kaplan, 1964; Root, 1993). As such, the theory is always “in progress,” and further research related to the theory is used to refine and increase confidence, or not, in the existing theory—hence the cyclical nature of applied theory building and continuous refinement. Which phase is actually carried out first depends on the theory-building strategy being used.

The following sections briefly describe each of the five phases of the General Method of Theory Building in Applied Disciplines. The book presents the phases from the perspective of a theory-to-practice strategy of applied theory building. Using a practice-to-theory strategy does not change the occurrence of these five phases, but rather what makes for the appropriate sequencing of each phase in the theory-building process.

Conceptualize

The Conceptualize phase requires that the theorist formulate initial ideas in a way that depicts current, best, most informed understanding and explanation of the phenomenon, issue, or problem in the relevant world context (Dubin, 1978; Lynham, 2000b; Van de Van & Johnson, 2007). The purpose of this phase is to develop a sound conceptual framework that provides an initial understanding and explanation of the nature and dynamics of the realm, problem, or phenomenon that is the focus of the theory.

The process of conceptualization varies according to the theory-building strategy employed by the theorist. However, at a minimum this process will include the development of the key elements of the theory, an initial explanation of their interdependence, and the general limitations and conditions under which the theoretical framework can be expected to operate. The output of this phase is an explicit, conceptual framework that often takes the form of a model and/or metaphor that is developed from the theorist’s knowledge of and experience with the phenomenon, issue, or problem concerned (Dubin, 1978; Kaplan, 1964).

The Conceptualize phase is one of two phases that dominate the deductive hypothesizing and theorizing component of theory building in applied disciplines. Here the theorist conducts scholarly inquiry into the realm, phenomenon, or problem that is core to the theory. Starting the process at this point is often more typical of quantitative (or experimental) type theory-building research methods—for example, the hypothetico-deductive method and meta-analysis (Hearn, 1958; Kaplan, 1964; Patterson, 1986). More qualitatively oriented theory-building strategies, like case study, grounded theory, and social constructivist approaches, typically begin with inquiry in the Apply phase and then use the results of such inquiry to guide the development of the theory’s conceptual framework (Eisenhardt, 1995; Stake, 1994; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Regardless of the sequencing of the Conceptualize phase of theory building, the development of a logical and sound conceptual framework is fundamental to all theory building. This theoretical framework is essentially the core explanatory capacity of any theory.

Operationalize

The purpose of the Operationalize phase of theory building is essentially an explicit connection between the Conceptualize phase and practice. The operationalization of a theory needs to be confirmed or tested in its real-world context. In order for the theoretical framework to evoke trust and confidence, the initial explanation of the realm, phenomenon, problem, or issue embedded in the framework must be applied to and empirically confirmed in the world in which it occurs. To achieve this necessary confirmation, the theoretical framework must be translated, or converted, into observable, confirmable components/elements. These components/elements can be in the form of confirmable propositions, hypotheses, empirical indicators, or knowledge claims (Cohen, 1989). They are addressed through appropriate inquiry methods determined by the strategy being employed by the theorist.

The Operationalize phase reaches toward an overlap between the theory and practice components of the theory-building process. A primary output of the theorizing component of applied theory building is an operationalized theoretical framework—that is, a logical and sound theoretical framework that has been converted into components or elements that can be further investigated and confirmed through rigorous research and relevant application.

Confirm

The Confirm phase falls within the practice component of applied theory building in applied disciplines. This phase involves the planning, design, implementation, and evaluation of an appropriate research agenda and studies to purposefully confirm or disconfirm the theoretical framework central to the theory. When adequately addressed, this third phase results in a confirmed and trustworthy theory that can then be used with some confidence to guide better action and practice. The theory is disconfirmed when it falls short.

Apply

A theory that has been confirmed in the contextual world to which it applies (i.e., operationalized) and has, at least to some extent, gone through inquiry in the practical world is not enough. A theory must also be threaded through the Apply phase. The application of the theory to its selected realm, problem, or phenomenon falls in the practice component of the theory-building method. Application of the theory enables further study, inquiry, and understanding of the theory-in-action.

An important outcome of this Apply phase is to enable the theorist to use the experience and learning from the real-world application of the theory to further develop and refine the theory. It is in the application of a theory that practice gets to judge and inform the theory’s usefulness and relevance for improved action and problem solving (Lynham, 2000b; Van de Ven & Johnson, 2007). And, it is through this application that the practical world becomes an essential source of knowledge and experience for ongoing development of applied theory (Ruona & Lynham, 1999; Swanson, 1997).

Refine

Because a theory is never “complete,” the theory must be continually refined and developed (Cohen, 1989; Root, 1993). This recursive aspect of theory building in applied disciplines requires the ongoing study, adaptation, development, and improvement of the theory-in-action. The Refine phase ensures that the relevance and rigor of the theory is continuously attended to and improved on by theorists through further inquiry and application in the real world. This continuing phase marks a further overlap between the practice and theory components of the theory-building process in applied disciplines. It addresses the theorist’s responsibility of continuous attention to the theory’s trustworthiness and substantive quality (Dubin, 1978; Van de Ven, 1989). The intentional outcome of this phase is thus to ensure that the theory is kept current and relevant, and that it continues to work and have utility in the practical world. It also ensures that when the theory is no longer useful or is found to be “false,” it is shown to be as such and adapted or discarded accordingly.

LIMITATIONS OF THE GENERAL METHOD

Like all multidimensional models presented in a two-dimensional media, the five-phase method of theory building is much less programmatic than Figure 3.1 might suggest. These phases of theory building are not so much linear as they are necessary. The process of theory building can begin with any one of these phases and progress in a much less orderly way than the graphic model might suggest. Where one begins and ends with applied theory building is less relevant than the acknowledgment that all of the five phases presented in the method are necessary to generate a relevant, useful, and trustworthy theory.

Those involved in applied theory building can use this five-phase method as a generic yet informative organizer and guide. They can also use it as a means to compare and contrast supporting strategies and tools as to their contributions to the general method.

THE IMPORTANCE AND CHALLENGES OF THEORY BUILDING

Over the last decade, scholars have increasingly recognized the importance of theory building to the professions (Chalofsky, 1996, 1998; Gradous, 1989; Hansen, 1998; Hatcher, 1999; Lynham, 2000a, 2000b; Marsick, 1990a, 1990b; Mott, 1996, 1998; Passmore, 1990; Shindell, 1999; Swanson, 1997, 1999, 2001, 2007a, 2007b; Swanson et al., 2000; Swanson & Holton, 2001; Torraco, 1997, 1999). These scholars and others suggest that theory building can (1) play an important role in advancing professionalism and maturity in the field, (2) help to dissolve the tension between research and practice, and (3) enable the development of tools for advancing theory and practice.

Theory—and, by association, theory building—acts to improve and protect research and practice in applied disciplines. It does this by providing a means of rigor and relevance for reducing both atheoretical practice (Swanson, 1997) and nonscientific inquiry (Lynham, 2000b). Having recognized the importance of theory building to applied disciplines, it is necessary also to recognize that theory building comes with certain challenges (Hansen, 1998; Klein, Tosi, & Cannella, 1999; Kuhn, 1970). The first of these challenges is handling the pressure that theory building puts on the relationship between the researcher and the practitioner. The second is the need to recognize that the outcomes of theory building in applied disciplines are enriched by building theory from multiple investigative perspectives and tools.

CONCLUSION

This chapter presented an overview of the General Method of Theory Building in Applied Disciplines. Specifically, it presented a framework of five core phases of the applied theory-building process: Conceptualize, Operationalize, Apply, Confirm, and Refine. The following chapters explore the five phases in detail and provide case examples.

A common myth associated with theory is that theory is all good and well, but it seldom can be expected to work in the real world. In an applied discipline, however, theory is good precisely because of its utility in practice. No one underscores the utility of good theory more than Lewin (1945, 1951), who long since coined the notion that there is nothing quite as practical as good theory. This utility-relevance requirement of theory in an applied discipline has been increasingly echoed by scholars of theory building.

Although relevance-utility is seen as a necessary condition of theory in applied disciplines, it is also agreed that good, applied theory must be extended to include the conditions of scholarly rigor and trustworthiness. It is this dual condition of what Marsick (1990) refers to as rigor-relevance that makes theory building useful in reducing the occurrence of atheoretical practice (Swanson, 1997, 2007) and related nonscientific inquiry (Lynham, 2000b).

Another misconception commonly associated with theory building is not only that the task of this scholarly endeavor is primarily the responsibility of the academic researcher, but that the origins of theory come essentially from research. Allaying this concern, Swanson (1997) provides us with clear logic and evidence of the multiple practice/development/research origins of theory and the corresponding researcher-practitioner nature of theory builders.

What does appear to be common to theory building in applied disciplines, regardless of the origins and interest of the theory builders, is the virtuous, systemic nature of the relationship among disciplinary theory, inquiry, and practice. This systemic nature of applied discipline theory building is fundamental to understanding and being able to participate in the process. The method is framed by the five interdependent and interacting phases of theory building: Conceptualize, Operationalize, Confirm, Apply, and Refine. This method is further useful in that it makes explicit the logic-in-use embedded in the methods of theory building. It also helps to address one of the current difficulties of applied discipline theory building: the generally perceived inaccessibility and often academically viewed nature of theory-building methods—a common deterrent to the aspiring practitioner-theorist.

Applied discipline theory-building methods are of a dual deductive-inductive nature. Although some methods may begin with deduction, at some point they become informed by induction. With other theory-building methods, the relationship between deduction and induction may be the other way around. Whether starting with theory and then moving to research and/or application, or vice versa, the choice of specific theory-building strategies and tools should be based on the nature of the realm, phenomenon or problem that is the focus of the theory-building endeavor, and not by the theorist’s preferred specific methodology. Multiple methods of theory building can and should be used to develop theory in applied disciplines. Just as each specific method of applied theory building is a way of developing insight, understanding, and possible explanation of the phenomenon, issue, or problem, so it is a way of not doing so (Passmore, 1997).

With integrated, inclusive, and multiple methods perspectives and approaches to building theory in applied disciplines, there is a better chance that the resulting theories will reflect the rigor-relevance characteristic of good, applied theory. In turn, these theories are likely to result in better outcomes and understanding for improved research, practice, and education.