10

Case Example: Chermack’s Scenario Planning Theory

THIS CHAPTER ILLUSTRATES the direct application of the General Method of Theory Building in Applied Disciplines to creating a new theory. Scenario planning has been claimed as a strategic learning tool (Chermack & Swanson, 2008), and numerous organizational scholars have contributed to its development (Healey & Hodgkin-son, 2008; Keough & Shanahan, 2008; Korte, 2008; McWhorter, Lynham, & Porter, 2008; van der Merwe, 2008; Wack, 1985). In this case example, the task is to illustrate each of the five phases in building a theory of scenario planning (Chermack, 2004a, 2005). Specifically, this chapter will

• describe the Conceptualize phase as applied to scenario planning,

• discuss the Operationalize phase as applied to scenario planning,

• examine the Apply phase as applied to scenario planning,

• describe the Confirm phase as applied to scenario planning,

• describe the Refine phase as applied to scenario planning, and

• discuss a set of quality indicators that have been applied to scenario-planning theory-building work.

WHAT IS SCENARIO PLANNING?

Scenario planning is a method involving group participation that aims to help shift participants’ perceptions of their external environment. The shift is critical in helping the organization achieve its goals in an uncertain environment. The intended outcomes of scenario planning include individual and team learning about driving forces of change in the business environment, integrated decision making, integrated understanding of how the organization can achieve its goals amid uncertainty, and increased dialogue among organizational members.

These outcomes collectively allow individuals and the organization to be better prepared for a variety of circumstances that an uncertain future can present. Scenario planning functions as a series of workshops, interviews, and team-based activities. Scenarios are narrative stories that follow particular paths into the future based on research, trends, and the key concerns of the people who will use them (Schwartz, 1991; van der Heijden, 2005; Wilson & Ralston, 2006). Scenario planning is a disciplined method for imagining possible futures that companies have applied to a great range of issues. For example, Royal Dutch/Shell has used scenarios since the early 1970s as part of a process for generating and evaluating strategic options (Wack, 1985).

The use of scenario planning in organizations has increased significantly since Shell’s reported success in using scenarios to avoid the impacts of the oil crises in the 1970s and 1980s (Ramirez, Selsky, & van der Heijden, 2008). More recent applications of scenario planning have expanded to include urban planning, health care, and small businesses.

An integrative framework for scenario-planning practice was established (Chermack, 2011) based on sound research, theory, and practice. Integrating previous literature until the year of publication, this theory proposed a framework for practice that could accommodate various other approaches to scenario planning. The remainder of this chapter describes the development of that framework according to the processes described in this book.

THE CONCEPTUALIZE PHASE OF THE SCENARIO-PLANNING THEORY

The initial attempt at constructing a theory of scenario planning (Chermack, 2004a) was based mainly on the scenario-planning literature, as little empirical research had been conducted on the topic. The effort was deductive, beginning with an extensive knowledge of the literature and then working toward the development of key concepts that ultimately function together in a system that can be called a theory (Dubin, 1978).

Specific strategies used to develop the concepts included an integrative literature review, conversations with practitioners, analysis of individual experiences, philosophical orientation considerations, imaging, systems diagramming, and a focus on involved and related variables. These practices led to a clear direction in terms of the overlap generated by considering all of the results.

Step 1—Defining the Concepts

Almost all of the strategies described in the Conceptualize phase of theory building were used to generate five key concepts in a theory of scenario planning (Chermack, 2004a, 2005): (1) organizational learning, (2) mental models, (3) decision making, (4) organizational performance, and (5) dialogue—a concept added after receiving feedback from practitioners. Using the five concepts in a systematic way was the scenario-planning framework’s method to produce the results claimed by practitioners. The addition of this fifth element can be viewed as a form of continuous refinement while still working in the Conceptualize phase. It is a good example of the nonlinear nature of theory building and the lesson that a theorist will typically jump around among the phases.

Step 2—Organizing the Concepts

Visualizing the concepts and organizing them into a configuration that was satisfactory to the theorist involved the use of sticky notes and systems diagramming. Over the course of six months, researchers tested several such configurations using whiteboards to help visualize the process until arriving at the final configuration.

Step 3—Defining the Boundaries

A decision was made to bound the theory of scenario planning at the organizational level. Certainly, arguments can be made for broad definitions of organizations, but it was generally taken to mean that the theory of scenario planning was intended to apply to for-profit or nonprofit organizations that are not too broad, possess a tangible distinctiveness, and have operated with a sense of continuity over time (Albert & Whetten, 1985).

In large, global organizations, adjustments may be required to accommodate the overall size of the organization. Wack (1985) offered the following useful summary:

Scenarios are like cherry trees: cherries grow neither on the trunk, nor on the large boughs; they grow on the small branches of the tree. Nonetheless, a tree needs a trunk and large branches in order to grow small branches. The global, macro-scenarios are the trunk; the large branches are the country scenarios developed by Shell operating companies, in which factors individual to their own countries—predetermined and uncertain—are taken into account and added. But the real fruits of the scenarios are picked at the small branches, the focused scenarios that are custom tailored around a strategic issue or a specific market or investment project. (p. 83)

So, in cases of large, global organizations, multiple rounds of scenario building may be required at the regional or business process level for the process to be successful. However, the ultimate bounding of the theory was still at the organizational level. Cases exist of scenario planning used at the city and national levels; although these have yielded case studies, no coherent program of research has emerged from more eclectic applications of scenario planning.

OPERATIONALIZE PHASE OF THE SCENARIO-PLANNING THEORY

Because of a general lack of empirical research on scenario planning, the theorists decided to use Dubin’s (1978) approach to theory development. Operationalization therefore proceeded with straightforward identification of propositions, empirical indicators, and hypotheses.

Step 1—Describe the Propositions of the Theory

The concepts identified in the conceptual development phase drove the propositions. In other words, each concept had a logical reason for being selected as a part of the theory, and the logic for inclusion was clarified in the propositions as well, as a clue to the directional relationships expected.

Proposition 1: If scenarios are positively associated with learning, then learning will increase as a result of participation in scenario planning.

Proposition 2: If learning is positively associated with the alteration of mental models, then mental models change as a result of learning.

Proposition 3: If a change in mental models alters decision structure, then a change in mental model implies a change in the approach to decision making.

Proposition 4: If changes in decision making are positively associated with firm performance, then firm performance will improve as a result of altered decision-making strategies.

Proposition 5: If scenarios are positively associated with dialogue, conversation quality and engagement, then dialogue, conversation quality, and engagement will increase as a result of participation in scenario planning.

Step 2—Describe the Results Indicators

Scenarios work like an on/off switch: the use of scenarios initiates the process the theory attempts to explain. If scenarios are used as the basis of the planning exercise, then the theory associated with scenario planning is expected to be able to explain the outcomes of the planning exercise. The empirical indicators begin with measurements of learning and are as follows:

Empirical Indicator 1: The value of concept (learning) will increase as a result of participation in scenario planning as measured by the Dimensions of Learning Organization Questionnaire.

Empirical Indicator 2: The value of concept (mental models) will increase as a result of participation in scenario planning as measured by the Mental Model Style Survey.

Empirical Indicator 3: The value of concept (decisions) will increase as a result of participation in scenario planning as measured by the General Decision Making Style Survey.

Empirical Indicator 4: The value of concept (performance) will improve as a result of participation in scenario planning as measured by any instrument that measures firm performance.

Empirical Indicator 5: The value of concept (dialogue, conversation quality and engagement) will increase as a result of participation in scenario planning as measured by the Conversation Quality and Engagement Checklist.

The empirical indicators fall in line with a logical extension of the concepts and an appropriate measurement instrument. A detour was required for empirical indicator 2: there was no existing measure of mental models that was appropriate for the context of scenario planning. Existing measures of mental models were driven by interview transcription analysis and mind-mapping software that did not yield a useful way to compare mental models across a variety of participants. Through two years of instrument development and initial validation studies, Chermack, Song, Nimon, Choi, and Korte (2012) established the Mental Model Style Survey, developed specifically for application in scenario planning and organizational change contexts. The survey was later expanded and examined in a different setting (Chermack, Glick, Cumming, & Veliquette, 2011).

Otherwise, the measurement instruments used to assess the theory of scenario planning were selected based on access, brevity, utility, and track record. The theorists invested a considerable amount of time in learning about the available measures in each domain of interest, conducting library searches and literature reviews, and skimming previous research that used the instruments before making a selection in each case.

Step 3—Develop Research Questions

The research questions for the proposed theory of scenario planning followed a logical connection to the results indicators described in the previous step. Developing research questions was a relatively simple exercise in the context of the scenario-planning theory because the philosophical orientation and research paradigm allowed the research questions to emerge based on the stepped work up to this point. The research questions each framed a separate study on scenario planning:

• What are the effects of scenario planning on learning organization culture?

• What are the effects of scenario planning on participant perceptions of mental models?

• What are the effects of scenario planning on participant perceptions of decision-making styles?

• What are the effects of scenario planning on objective measures of organizational performance?

• What are the effects of scenario planning on participant dialogue, conversation, and communication skills?

These research questions came directly from the process of specifying propositions and identifying results indicators. They all took the same structure and form based on best practices in quantitative research methods.

CONFIRM PHASE OF THE SCENARIO-PLANNING THEORY

The theorists conducted several studies over approximately ten years to confirm the theory of scenario planning. Because there was a variety of relationships to assess, they selected a study design that would support the greatest power in answering the research questions that could be easily replicated in multiple studies.

Step 1—Design the Inquiry Study

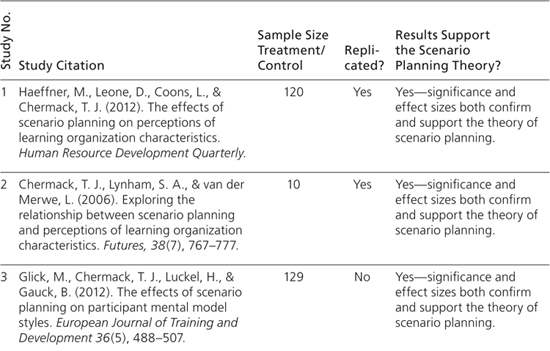

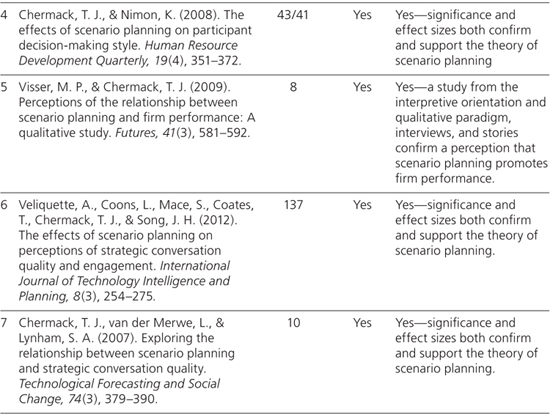

The theorists chose a quasi-experimental research design as the frame for all of the theory research conducted because it is the design best suited to answer the research questions posed. The approach was a pretest/posttest, treatment/control group design. This enabled observed changes in a treatment group to be checked and attributed to the intervention (scenario planning) because the control groups showed no changes. A summary of these research studies is provided in Figure 10.1.

Because the lead theorist was affiliated with a research university, in all cases Internal Review Board (IRB) permission was sought and granted according to university research rules and regulations. IRB approval ensures the integrity of the research and that human subjects were given the proper treatment as research protocols dictate.

Step 2—Collect and Analyze Data

In all of these studies, data were generally collected and analyzed the same way. Each study involved the theorists gathering pretest survey results from participants in the first scenario-planning workshops. Surveys were printed in hard copies, and participants filled them out in real time, in a process that was built into the workshops (Glick, Chermack, Luckel, & Gauck, 2012, p. 498). Participants self-selected a code so that pre- and posttests could be matched. Posttest data were collected at the final scenario workshops, again in hard copy. Data were entered into a computer and analyzed with SPSS, which is a statistical software package that can perform a variety of complex statistical analyses.

FIGURE 10.1 Inquiry Studies Examining Chermack’s Theory of Scenario Planning.

Step 3—Connect the Results to the Theory

Four of the five research studies have been replicated, and four of the five research studies used a quantitative research paradigm. All of the four studies from the quantitative research paradigm used significance tests and calculated effect sizes to make more powerful statements about changes in the data as a result of the scenario-planning intervention. These studies supported the theory of scenario planning, as significant results were found with medium to large effect sizes. In other words, the relationships found between scenario planning and these four content areas were compelling and directional in favor of how it was theorized. The study that used a qualitative research paradigm featured interviews with a variety of organizational decision makers who had used scenario planning within the previous three to six months. Participants were asked to reflect on the utility of scenario planning and give specific examples of how the exercise may have influenced or would influence their firm performance. Again, in all cases specific attention was given to what the study results meant in terms of the accuracy of the theory.

APPLY PHASE OF THE SCENARIO-PLANNING THEORY

The eventual outcome of the research studies described in the previous section was a book titled Scenario Planning in Organizations (Chermack, 2011). The book is a practically focused work that uses the theory of scenario planning to develop an approach to practicing it. It describes practical procedures that can be used in workshops that will result in improved performance in the areas studied.

Step 1—Analyze Problems

Over the past ten years, the lead theorist also engaged in the practice of scenario planning. Various problems were addressed with the scenario method, and the common factor for all of them was uncertainty around a decision that needed to be made. The scenario-planning method can address various problems, from specific issues like investing in a new product or technology to something as broad as exploring the future of the industry. Emerging from a decade of practice of scenario planning, the theorist discovered that uncertainty in decision making was the common factor that influenced strategy development.

Step 2—Propose, Create, and Implement Solutions

Because of detailed study according to rigorous criteria in the variety of inquiry studies, the theorist was able to delineate several processes and process steps required to apply scenario planning according to what the theory suggested. Stated another way, the theory drove the development of practical procedures that could be applied in any organization. Again, a variety of clients have sought scenario planning over the last ten years; and each case, while unique, presents some similar characteristics. Each instance of application received a version of the processes borne out from the theory-based investigation of scenario planning. Some cases were facilitated more rapidly than others, and some simply took more time. However, the end result has been that as long as some basic hallmark characteristics of scenario planning are fulfilled, the theory tends to operate as hypothesized.

Step 3—Assess Results

Practice results have indicated that scenario planning can be effectively deployed to address a variety of purposes in a variety of contexts. Some similarities are required, such as uncertainty in the environment and open minds. The set of anecdotal evidence in the form of written reports to project stakeholders, including an analysis of results, indicate a successful theory-building project.

Continued practice and inquiry is, of course, required. Consistent project feedback is not focused on potential inaccuracies of the theory; rather, it is focused on what might be missing from the original Conceptualize phase of theory building. Specifically, clients have indicated that perhaps elements like trust, engagement, resilience, grief, change management, and a clearer link to strategy could be reasonable and logical elements of a theory of scenario planning. Because of this feedback, the theorist is directed back to the Conceptualize phase for considering continuous refinement opportunities.

REFINE PHASE OF THE SCENARIO-PLANNING THEORY

The Apply and Refine phases are closely linked, with the lines between them blurred. A decade of practicing scenario planning while following theoretically sound ideas has led the theorist to the possible inclusion of multiple additional elements of the theory. For example, as noted, feedback from practice has suggested that organizational trust, employee engagement, employee resilience, coping with grief, and complex change management are all areas where scenario planning could foreseeably play a supporting role. Thus, the theorist returns to the Conceptualize phase to consider including these elements in the theory. Where and how they fit into the original theory is unclear and requires a significant amount of literature review and synthesis.

To add to the Operationalize phase and include these constructs requires yet even more scholarly work in determining appropriate instruments. However, the general research design is already established; and once measurement instruments are found, inquiry studies could be generated quite quickly. In fact, inquiry studies for each of these variables are all underway as of the date of this publication, and results will be reported in scholarly journals similar to those cited earlier.

CONCLUSION

This chapter has illustrated each phase of theory building with reference to an actual theory-building project on scenario planning. The purpose was to give a concrete example of a real theory and to describe how each set of steps was accomplished. In addition, directions for future research and adjusting the theory based on research and practice were discussed.