6

Confirm Phase

CONFIRMATION OR DISCONFIRMATION is seen as a respectable end point for theory building in applied disciplines. Yet, that is not always the case, and concluding with confirmation actually falls short. You can imagine a theorist’s creative and active mind crunching knowledge and experience into a new solution that the theorist immediately tests so as to check it out. The outcome could be very important information that feeds into a more formal and revised conceptualization and operationalization of the theory. Furthermore, to confirm a theory is not a one-time event, yet initial efforts give the theorist enough direction to continue working on a theory, or scrap it and start over. The Refine phase dictates additional confirmation efforts that are often started in the Confirm phase.

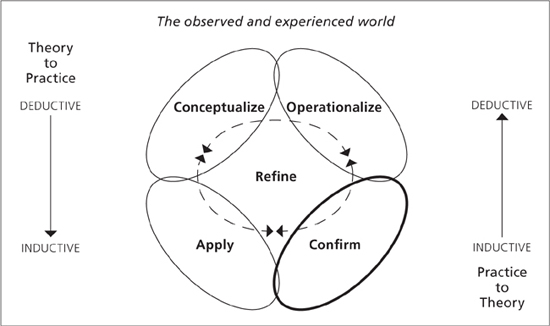

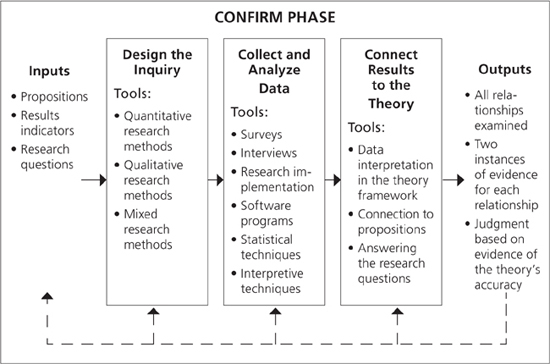

The purpose of this chapter is to describe specific approaches to the Confirm phase of theory building in applied disciplines (Figure 6.1). Specifically, this chapter will

• define the Confirm phase,

• describe the general inputs to this phase,

• summarize the pros and cons of confirmation approaches,

• describe the outputs of the Confirm phase, and

• describe quality indicators for the Confirm phase.

FIGURE 6.1 Confirm Phase of Theory Building in Applied Disciplines

WHAT IS CONFIRMATION?

The Confirm phase brings theorizing into the realm of research and disciplined inquiry, but requires its application to real situations. In this phase, theorists plan, design, implement, and evaluate a program of investigation to confirm or disconfirm whether the theory fits in the real world (Lynham, 2002a). The results of the confirm phase can establish a sense of confidence in the theory and steer the theorist into other phases for adjustments.

Virtually every inquiry study is a confirm/disconfirm activity. However, most authors of these studies are not clear about the role they play in assessing or contributing to a given theory. Because most theories involve numerous relationships, the Confirm phase almost always requires multiple instances of inquiry to make overall judgments about the theory.

The old Louis Jordan song “Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby?” comes to mind as a fun way of thinking about confirming or disconfirming. Both the romantic and the theorist have doubts, hopes, and are craving to know the answer!

Some of those lyrics of “Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby?” include:

Is you is or is you ain’t my baby

Well, the way you’re acting lately, well, it makes me doubt

You were still my baby, baby

But it seems like my flame in your heart, well, it’s just gone out. (Holley & Jordan, 1944)

Holley & Jordan’s lyrics go on searching for confirmation about whether his baby is still his baby or whether she found somebody new. For sure, doubts provoke a desire for confirmation.

John Shanley, the author of Doubt—the popular book, play, movie, and opera—takes great pleasure in audiences exiting with doubts about both the legality and morality of his story of religion, suspicion, pedophilia, and compromise.

On a much simpler and less esoteric level, we have confirmed that flat roofs leak and can make decisions accordingly.

INPUTS TO CONFIRMING THEORIES

The Confirm phase is a focused investigation within the theory-building process that requires theory implementation in practice. Other activities within the process can call upon theory-in-action or theory-in-practice, but in the Confirm phase it is mandatory.

The confirm/disconfirm investigation has features similar to most inquiry strategies—planning, design, implementation, and evaluation. These are all required inputs. Hundreds, if not thousands, of research methodology books are aimed at research methodology appropriate for confirming/disconfirming. We recommend these three resources:

Mohrman, S. A., & Lawler, E. E. (Eds.). (2011). Useful Research: Advancing Theory and Practice. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Swanson, R. A., & E. F Holton (Eds.). (2005). Research in Organizations: Foundations and Methods of Inquiry. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Trochim, W., & Donnelly, J. P. (2006). The Research Methods Knowledge Base (3rd ed.). Mason, OH: Atomic Dog.

The detail of an investigation is influenced by the complexity of the theory realm under consideration, the amount of effort already expended, and the fact that this phase in some cases will be complex and in others it will be simple. There is not one answer. Thomas Edison, the productive and famous inventor, spent an enormous amount of time learning in increments from confirmation. One of his profound quotes is “I have not failed. I’ve just found ten thousand ways that won’t work.”

In contrast to Edison, most theory investigators do not own an “invention laboratory” and need to more strategically set up their investigations. Their efforts at planning, designing, implementing, and evaluating an appropriate investigation are driven by the dominant research question arising from the maturation of the theory under development.

Approaches to Confirming Theories

As noted earlier, the apolitical research paradigm of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research has been adopted for this book. While ideological differences undergird many research paradigms, the intent here is to be aware of those differences and to be intellectually agile enough to move across paradigms logically, not ideologically. Logically, then, the challenge is to call upon the most rational approach to confirming, given the theory under investigation.

For example, a researcher drawn toward qualitative research methods and, more specifically, phenomenology needs to logically reach back to the research problem decision and the tentative research question posed in the confirmation effort. While the problem area is of high interest to the investigator, if the present status of the theory is not logically brought forward, he or she may naively choose a favored methodology (e.g., phenomenology) when there is already a great deal known related to the theory research question by the way of self-report and storytelling data. Another extreme case example could be the availability of extensive quantitative research on the topic—enough to justify a meta-analysis.

Quantitative Approach to the Confirm Phase. The quantitative orientation to theory building is based on the scientific method and traditional hypothesis testing. Reality is viewed as objective. The theorist’s task is to establish laws that can predict behavior in an area of human activity. The quantitative research process can be viewed as a five-step process (Holton & Burnett, 2005):

1. Determining basic questions to be answered by the study

2. Determining participants/setting for the study (population and sample)

3. Selecting the methods needed to answer questions

a. Variables

b. Measures of variables

c. Overall design

4. Selecting analysis tools

5. Understanding and interpreting the results

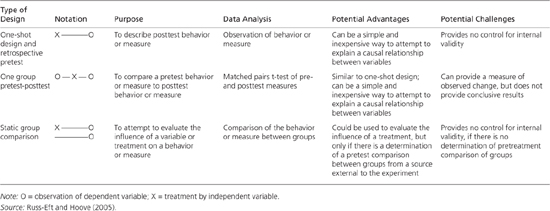

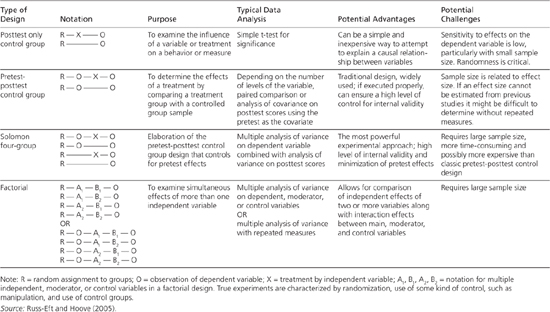

Most discussions about qualitative research present quasi-experimental and true experimental designs. Figure 6.2 offers an overview of pre-experimental designs, and Figure 6.3 overviews true experimental designs. The key aspect to experimental designs involves the random assignment to a treatment or a control group, which helps to ensure that the two groups are equivalent in terms of history and other preexisting circumstances or conditions that may influence the results.

Qualitative Approach to the Confirm Phase. It is useful to understand different models of knowledge as contributing different snapshots of the same realm. Quantitative research can yield broad trends and excellent demographic snapshots. It has limits in trying to understand “black box” processes (Guba & Lincoln, 1998; Lincoln & Guba, 1985, 2000), “lived experience” (Turner & Bruner, 1986), and how individuals and groups go about “sensemaking” in organizations (Weick, 1995).

FIGURE 6.2 Types of Preexperimental Design Showing Typical Purpose, Common Analytical Techniques, and Potential Advantages and Challenges for Each Design

FIGURE 6.3 True Experimental Designs

Researchers pursuing qualitative studies look for instances of knowledge creation, new insight, and new understanding—both in their research participants and in themselves. Researchers are open to “invention and construction, activities that seemingly move away from objects and objectivity to subjects and subjectivity” (Weick, 1995, p. 36).

Qualitative methods offer the best possibility for understanding how individuals both make sense of and perform in their social and organizational worlds. Formal tests and measurements do not easily allow us to ask how individuals and groups make sense of their worlds. By observing and communicating face-to-face, investigators can come to understand the meaning-making strategies individuals create and depend on—a pattern form of theory. In pattern models, “something is explained when it is so related to a set of other elements that together they constitute a unified system. We understand something by identifying it as a specific part in an organized whole” (Kaplan, 1964, p. 333).

The utility of pattern theories is their sensitivity to, and reflection of, human systems, including organizational forms. One benefit of pattern theories is that they prompt researchers to see realms under study as pieces of more unified, interconnected, and holistic systems. When the understanding sought is the description of elaborate human groupings, patterns prove more helpful than partial or segmented deductions. Pattern theories are based on richness and redundancy. They are best formed with qualitative data aimed at collecting and preserving richness and complexity.

Mixed Methods Approach to the Confirm Phase. Applied disciplines often require, or may be best understood through, the use of multiple philosophical orientations that call upon a mixed methods approach to confirmation. This is often referred to as multiparadigm theory building. The multiparadigm approach to theory building is not as well articulated. Competing philosophical orientations pose varying problems for theorists that are not easily solved or settled. Yet, it is just these variations that offer the possibility of confirming/disconfirming from a mixed methods approach.

For example, grounded theory is a philosophical orientation focused on using data to generate hypotheses. Grounded theorists begin by collecting data in an area of human systems activity. The data are used to build hypotheses that are “grounded in the phenomenon” (Charmaz, 2006, p. 24) rather than formulated by the theorist ahead of time. The constant interplay between gathering and analyzing data is the dominant feature of this orientation—both qualitative and quantitative.

One theory journey we went on lasted over a decade. It started out with a corporate sponsor wanting to create a financial model for predicting financial return on their investments in formal employee training programs. The challenges took us in multiple directions, including financial accounting and analysis, systematic structured training, unstructured on-the-job training, individual performance, and organizational performance.

The starting point was to identify standard practices within these various realms and to operationalize them into a classic experimental study having treatment and control groups. The experimental study was successful, had face validity to the corporate sponsors, and provoked the further development of both a financial assessment theory and a performance improvement theory. Continued building of these two related theories were sometimes joined and sometimes separate. In both instances, quantitative and qualitative data were collected to answer relevant questions for the purpose of confirming/disconfirming the theories. These multiple efforts were mostly mixed methods case studies conducted within a single corporation. The goal was to confirm the theory-based tools through repeated application case studies in a wide variety of organizations.

The case study method is another strategy that is almost always a mixed methods approach. The case establishes clear boundaries for the theory-building effort and can purposefully accommodate a variety of data collection and analysis methods—quantitative and qualitative. Many argue for mixed methods case studies as being particularly useful in theory building (George & Bennett, 2005, p. 34).

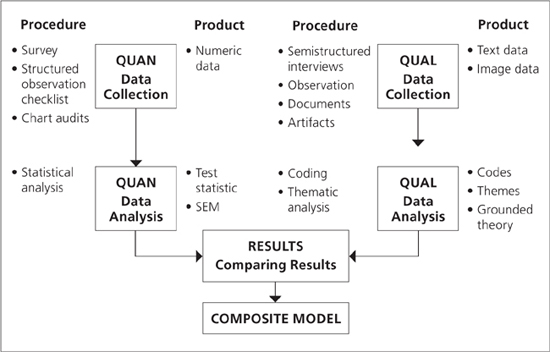

Mixed methods designs can have qualitative and quantitative investigations carried out in sequence or simultaneously (Creswell, Plano Clark, Gutmann, & Hanson, 2003) (see Figure 6.4). For example, a sequential explanatory design involves a quantitative data collection phase followed by a phase of qualitative data collection. This design is used to follow up on quantitative results from experiments, surveys, or correlational studies by in-depth probing of the results through qualitative data from focus groups, individual interviews, or observations. A similar design is the sequential exploratory design, which features qualitative data collection that is followed up with a phase of quantitative data collection. This design is typically used to develop quantitative instruments when the variables are not known or to explore preliminary qualitative findings from a small group of people with a randomized sample from a larger population.

FIGURE 6.4 Mixed Methods Concurrent Research Design

Source: Cresswell (2005).

Collecting both quantitative and qualitative data simultaneously allows the investigator to converge the data to make comparisons between detailed contextualized qualitative data and the more normative quantitative data. Practical implementation decisions often dictate whether the data will be collected sequentially or at the same time in a mixed methods confirmation/disconfirmation study.

THE CONFIRM PHASE OF THEORY BUILDING

Any attempt at confirming theories entails three generic and critical steps: (1) design the appropriate inquiry studies, (2) collect and analyze data, and (3) connect the results to the theory (see Figure 6.5). These steps are general, and as we have mentioned, literally thousands of books and guides are dedicated to designing various kinds of inquiry studies.

FIGURE 6.5 Steps in the Confirm Phase of Theory Building in Applied Disciplines

Step 1—Design the Appropriate Inquiry Studies

Designing inquiry studies requires familiarity with numerous parameters that come into play in disciplined inquiry. For example, sampling, identifying participants, gaining access to organizations, selecting an intervention, and refining interview questions are all part of research design. A particular phenomenon, an area of need, an organizational problem, variables, stories, and other factors come together based on the previous phases and give theorists material from which to design a research study. Because most theories go beyond a single research study, theorists usually have plenty of decisions to make, and numerous studies can be designed from a variety of perspectives and viewpoints. This set of completed studies has something to say about the theory and its fit with the real world.

Certainly research designs, philosophical orientations, and available resources will influence research design in the Confirm phase. Recalling clear research questions and drawing heavily from the Operationalize phase can help keep the theorist on track. Data collection strategies are important to plan out well ahead of time. Theorists must make decisions on the logistics of gaining access to research participants, purchasing access to databases, and other study elements. Survey data can be collected at site visits, online, or both. Interviews can be done face-to-face or on the phone, and at times a group interview strategy is useful. Inquiry often makes use of existing data, which usually requires some permission to access. Choices also must be made about data analysis, whether the study is quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. In other words, debates exist within theory orientations as to the best tools for certain tasks. For example, qualitative researchers often debate the use of software to analyze interview data. As for additional resources, we again point to selected research methodology texts that deal with specific research design strategies from a variety of orientations, paradigms, and methods (Mohrman & Lawler, 2011; Swanson & Holton, 2005; Trochim & Donnelly, 2006).

Step 2—Collect and Analyze Data

After all of the planning that goes into designing inquiry studies in theory research, the theorist eventually must collect and analyze the data. In this step, the theorist is carrying out the inquiry activity. Depending on the design, data collection can be a one-shot data grab, multiple data points, interviews over the course of months or more, or combinations of all of these. A variety of data analysis methods are tailor made to fit specific research designs. For example, the constant comparative analysis method (Guba & Lincoln, 1998) is a highly rigorous approach to analyzing interview data. If the inquiry uses a pretest/posttest design, the t-test is an appropriate technique. Theorists become experts in their research paradigms, eventually mastering a variety of specific techniques over the course of continued theory building. In the data collection and analysis step, the theorist is building a set of data related to the research question and applying the appropriate analysis techniques.

Step 3—Connect the Results to the Theory

To have the greatest impact on theory building, inquiry results must be written up from a theory perspective. That is, the results say something useful about the larger theory, and the connection must be made. In explicit theory-building research, inquiries are often carried out with the intent of investigation of a portion of some theory. However, in many cases the connection is lost because there is no real awareness of an overarching theory, or researchers undertake the inquiry to advance a specific technique rather than to contribute knowledge. It can be argued that every inquiry study makes a contribution to some theory. Responsible theorists and researchers recognize this relationship and point out how what is learned from disciplined inquiry influences the status of theory.

OUTPUTS OF THE CONFIRM PHASE

Outputs of the Confirm phase always require judgment. How much evidence is required to say a theory is accurate? Because most theories involve numerous relationships that are best examined in many research studies, a theorist can spend a lot of time in the Confirm phase before reaching any unified conclusion about the theory. Plus, there are barriers. Replication studies are not often found in applied disciplines. It seems that many journals, too, are publishing unique and novel contributions rather than continued investigations of specific aspects of human systems to build evidence. This situation reflects a tendency to judge one study with positive results as “enough.”

Amid the challenging state of inquiry in applied disciplines, the ideal output of the Confirm phase is a collection of inquiry studies that examine all of the proposed relationships in the theory with at least two instances of evidence for each relationship. This would ensure that all aspects of the theory are tested, and there are multiple instances of evidence to support each aspect. In the end, each theorist will have to make a judgment as to how much evidence is required to claim a theory as accurate.

A more realistic description of the situation is that theories grow and evolve in piecemeal fashion. A theorist may examine some portions of the theory, find evidence, and then move on to other parts of the theory. This iterative process can take years. It is also important for the theorist to make connections to application, which is the next phase of theory building to be discussed. If a theory, or part of a theory, is shown to be accurate, it must mean something for practice. Since most theorizing attempts to improve conditions, it follows that an ultimate outcome of theory building might be a better way to do something. What is learned through rigorous examination of a theory should result in reflections on how practice might be done differently; and conversely, application of the theory can provide fodder for needed revisions and confirmation.

In summary, the general outputs of the Confirm phase of theory building are (1) evidence on which to judge the fit or accuracy of the theory, (2) a judgment of the fit or accuracy of the theory, and (3) interpretation of what the judgment means for application (Figure 6.5). These three outputs will vary in depth and form for each theory exercise, but they must be drawn together by the theorist in a way that instills confidence that the theory captures some aspect of human and systems interaction with a degree of accuracy.

QUALITY INDICATORS FOR THE CONFIRM PHASE

The key quality indicators for the Confirm phase are drawn directly from Patterson’s (1986) criteria: (1) comprehensiveness, (2) empirical validity or verifiability, and (3) practicality. These three criteria are particularly relevant to this phase of theory building because they describe the desired outputs.

Comprehensiveness

A theory should be complete, covering the area of interest and including all known data in the field. Comprehensiveness also refers to all the relationships being examined before a judgment is made. Uninvestigated parts of a theory could be critical to its operation, and if left unknown, optimal understanding has not been reached. The assessment of the theory and all of its relationships should be comprehensive in order to draw the most useful conclusions.

Empirical Validity or Verifiability

A theory must be supported by experiences or experiments that confirm it. That is, in addition to its consistency with or ability to account for what is already known, a theory must generate new knowledge. However, a theory that is disconfirmed by experiment may lead indirectly to new knowledge by stimulating the development of a better theory. In short, a theory must have evidence to support it, plain and simple.

Practicality

One of the most important criteria for theory in general, which is seldom mentioned, is whether the theory is useful to practitioners in organizing their thinking. This criterion is also perhaps the most important output of the Confirm phase. A good theory must get practitioners beyond trial-and-error use of techniques. Instead, the goal is the rational application of principles. Theories must be useful, and they must change the way things are done within the human system they are intended to improve. Practicality is also the bridge to the next phase of theory building—the Apply phase.

There are numerous theories about how families, workplaces, communities, and nations change over time. Sociologist Robert Putnam discusses the challenges in measuring change as a part of confirming or rejecting theories. He and others lay out a similar argument, stating, “No single source of data is flawless, but the more numerous and diverse the sources, the less likely that they could all be influenced by the same flaw” (Putnam, 2000, p. 415). Looking at a single survey is not enough to confirm a theory. Survey data, along with institutional data and behaviors over time, provide the basis for change theory confirmation. Using multiple sources of data in conducting confirmational research is referred to as triangulation.

CONCLUSION

This chapter summarized the Confirm phase of theory building in applied disciplines. First, we reviewed general approaches and strategies for confirming or disconfirming theories; then we described the actual process. Given the vast amount of literature available concerning how to design inquiry studies, theorists should gather a variety of perspectives and detailed approaches in their paradigm area. Three general steps in the Confirm phase were discussed: (1) design the appropriate inquiry studies, (2) collect and analyze data, and (3) connect the results to the theory. We described these steps at a general level because their detailed execution depends entirely on choices made previously in the theory-building process.

We also looked at outputs and quality indicators for the Confirm phase. The core work of this phase is to assess the adequacy of the theory through rigorous inquiry studies. Ultimately, a slew of evidence for all of the relationships that wind up in the theory is required to support it and establish its fit with the real world. Finally, the theorist must make interpretations about what a confirmed theory means for working in human-made systems and how some aspect of it should be changed.