4

Conceptualize Phase

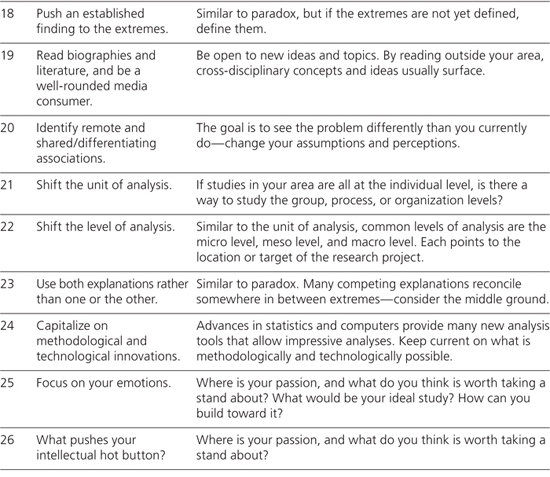

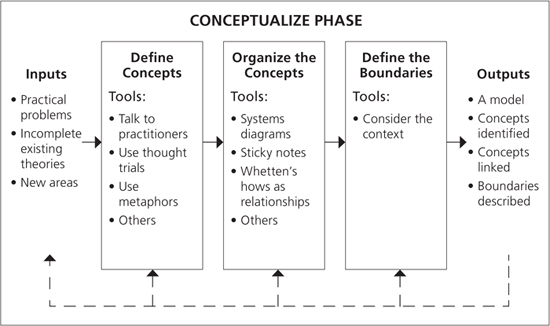

CONCEPTUAL DEVELOPMENT is a common starting point for theory building in applied disciplines. Thus, much more has been written about this phase compared to the others. The purpose of this chapter is to describe specific approaches to the Conceptualize phase of theory building in applied disciplines (Figure 4.1). Specifically, this chapter will

• define and describe the Conceptualize phase,

• describe the general inputs to the this phase,

• summarize the pros and cons of four approaches to the Conceptualize phase,

• describe the outputs of the Conceptualize phase, and

• propose a set of quality indicators for Conceptualize phase outcomes.

WHAT IS CONCEPTUAL DEVELOPMENT?

Conceptual development is the specification of the key elements of the theory, an initial explanation of their interdependence, and the general limitations and conditions under which the theoretical framework can be expected to operate. “The output of this phase is an explicit and thought-out conceptual framework that often includes a model or metaphor developed from the theorist’s knowledge of and experience with the realm, issue, or problem” (Lynham, 2002, pp. 231–232).

FIGURE 4.1 Conceptualize Phase of Theory Building in Applied Disciplines

Conceptual development in applied disciplines constitutes the major idea that can become a theory, but it is not by itself a theory. Much of the existing theory-building discussion and literature remains in this realm only. In fact, few scholars move their theoretical ideas into the other essential phases of theory building (Halbesleben, Wheeler, & Buckley, 2004). Furthermore, much of what constitutes popular management, business, and other applied discipline books almost always remain in this state—they do not make measureable, useful, or applicable theory contributions. They get stalled as untested hypotheses. This is why so many people disparagingly say, “That’s just a theory.” In a context like this, scholars are actually proposing untested hypotheses.

Change in our lives is almost a universal. Surprisingly, Who Moved My Cheese? by Spencer Johnson and Ken Blanchard (1998) is the top-selling business book of all time. This elementary fable lets readers know that the idea and reality of change is upon us, and the bottom line is for individuals to suck it up, go for it, and that they may like it. The problem is that the book in no way is grounded in sound change theory, nor does it advance the theory of change. Added to this insult was the avalanche of corporate leaders requiring underlings to read the 96-page fable with the implicit message that these employees who had been working in bad systems were the ones to absorb the change. Nowhere in the scenario was there mention of leadership responsibility for irrational change that inflicted employee layoffs, questionable restructuring, frenetic mergers, and general chaos. Where’s the cheese?

INPUTS TO CONCEPTUAL DEVELOPMENT

Initiation of conceptual development in applied disciplines comes from (1) practical problems, (2) incomplete existing theories, or (3) new areas of human activity. Any of these three situations signal a need for conceptual development work. For example, nurse practitioners may experience problems in their work that push them to understand and explain what is happening. Or a manager might be confronted with deviations that do not fit existing explanations or theories. New activities that have not been explained can also create a need for conceptual development, such as virtual team behavior. All of these situations require gaining a new understanding.

The careful observer can see that inputs to conceptual development can come from research, theory, and practice. In other words, any of the other phases presented in the General Method of Theory Building in Applied Disciplines can involve situations that push the theorist into the conceptual development phase. Emphasizing, again the integrative and cyclical nature of theory building, we remind you that the theorist can begin anywhere in the model. There are no defined starting and ending points, which increases the complexity and ongoing nature of theory building.

Matthew Crawford, philosopher and motorcycle mechanic, wrote a best-selling book on the inquiry into the value of work called Shop Class as Soulcraft (2009). It is a fun starting point to think about theory building in applied disciplines. Crawford has a PhD in philosophy and uses the verbal tools of philosophy to argue that he has had “a greater sense of agency and competence . . . doing manual work, compared to other jobs that were officially recognized as ‘knowledge work.’ Perhaps most surprisingly, I often find manual work more engaging intellectually” (p. 5).

Crawford relies on his work as a motorcycle mechanic to thread the reader through his view of the world. As it stands, it can be classified as an engaging contribution for a philosophical theory of work—not a contribution to an applied discipline of work theory.

Crawford’s book is rich with intellectual argumentation and application examples. While this is a philosophical exposé, the book has great potential to raise important applied questions about work theory. His purpose was not to build an applied theory of work. Yet, a careful reader could go through the pages and extract information to conceptualize and operationalize an applied theory of work based on the book.

PROCESSES FOR CONCEPTUAL DEVELOPMENT

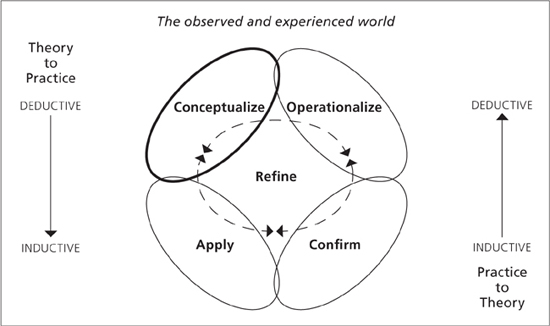

The primary purpose of this chapter is to provide tools for scholars to engage in conceptual development. Four conceptual development methods are presented that align with four different philosophical orientations. They include the quantitative approach in Dubin’s (1978) theory-building process (steps 1–4), the grounded theory approach in Whetten’s (2002) modeling as a theorizing process, the social construction approach in Weick’s (1989) theory building as disciplined imagination, and a case-study approach in Storberg-Walker’s five components (Storberg-Walker & Chermack, 2007). These methods provide complementary ways of completing the conceptual development phase. Some reflect very clear philosophical alignment, while others do not. They can be integrated or used simultaneously by the theorist. The conceptual development phase is less constrictive than some other phases in terms of philosophical orientation. Theorists are free to use a variety of approaches and tools. Use what works and what is helpful in generating a set of linked concepts that describe and explain some domain of human activity.

Quantitative Approach: Dubin’s Theory-Building Method (Steps 1–4)

Dubin’s (1978) methodology involves eight steps, with the first four steps focused on conceptualization. The full eight steps include (1) developing the units of the theory, (2) specifying the laws of interaction describing the relationships among the units, (3) determining the boundaries within which the theory is expected to function, (4) identifying the system states in which the theory is expected to function, (5) specifying the propositions, or truth statements, about how the theory is expected to operate, (6) identifying the empirical indicators used to make the propositions testable, (7) constructing hypotheses used to predict values and relationships among the units, and (8) conducting research to test the predicted values and relationships. The first four conceptual development steps are described as follows:

Step 1—The Units of a Theory. For Dubin, the units of the theory are the building blocks of a theory. Units are the basic concepts that must come together to form a theory. In Dubin’s approach, effort is spent defining units that work together in the functioning theory, and his subprocesses for defining and combining units are also very detailed.

Step 2—Laws of Interaction. Laws of interaction describe the relationships among the different units. Relatedness does not imply causality. For example, when riding in an airplane, you might experience turbulence. Often immediately before the plane shakes, the “fasten safety belt” sign comes on. These two events can be described as related, but the “fasten safety belt” sign turning on does not cause turbulence. At this stage, relationships are the focus; and if causality is suspected, it should be made clear here but tested later.

Step 3—The Boundaries of a Theory. Boundaries describe the limits of the theory and set the context in which the theory is meant to operate. Boundaries are important so as not to overinterpret the intentions and reality of the theory under development.

Step 4—System States. System states describe distinct characteristics of the theory while it is in operation. In other words, system states are descriptions of separate discreet phases or transitions the theory must evolve through in order to operate. For example, human beings have two discreet system states, awake and asleep (Dubin, 1978).

This approach is a very detailed and process-driven approach to conceptual development. Dubin (1978) called the results of conceptual development a “theoretical model.”

Quantitative Approach: Whetten’s Modeling as Theorizing

Whetten (2002) presents a clear method for conceptual development. Steps include (1) identify constructs answer the question—“What?”; (2) understand the relationship(s) between the constructs answer the question—“How?;” (3) identify the assumptions undergirding the relationships answer the question—“Why?;” (4) identify the context(s) of the theory answer the questions—“When? Where? Who?.” Each step is described briefly here:

Step 1—“What” as a Construct. Whetten recommended using sticky notes to represent the major pieces of the theory. “The sticky notes can then be rearranged as the introduction of new constructs or as the logic of the theorist evolves.” (Storberg-Walker & Chermack, 2007, p. 510).

Step 2—“How” as a Relationship. Whetten (2002) emphasized the relationships between the constructs being key to moving from ideas to theory. ‘First, be aware that there is no consensus regarding the language of how’ (p. 55). Theories should use a variety of techniques to describe relationships. ‘Second, keep in mind that many of the more detailed and technical discussions of relationship types or forms have a strong methodological orientation’ (p. 55); and third, ‘All organizational scholars need to come to terms with the nettle-some issue of causality in social science research’ (p. 56). Just where does the theorist intend for causality to enter the new conception of the content area, if at all?

Step 3—“Why” as Conceptual Assumptions. Conceptual assumptions are the fundamental organizing principles that support the theory (Whetten, 2002). These assumptions frame the logical reasoning behind the choice of constructs and definition of their relationships. For example, Becker’s human capital theory involves the concepts of education and income, among others. According to Whetten, the conceptual assumptions would be required to provide a logical reasoning for including these concepts and to define how they are related to each other.

Step 4—“When/Where/Who” as Contextual Assumptions. Contextual assumptions identify the boundaries of the theory (Storberg-Walker & Chermack, 2007, p. 511). Boundaries simply locate the theory in the larger domain by defining the specific area of human system activity (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Hackman & Oldham, 1980). Contextual assumptions can include categories based on industry, culture, and other factors that establish the limits of the theory.

Qualitative Approach: Weick’s Theorizing as Disciplined Imagination

“Weick (1989) outlined an approach he believed to be more supportive of theorizing as a process involving imagination, representation, and choice” (Storberg-Walker & Chermack, 2007, p. 506). The concern is “with how to get the theory-building effort started” (Storberg-Walker & Chermack, 2007, p. 506) and allowing theorists room to let the imagination influence the theory-building process. As a result, his approach is not linear. Instead, he provided three tools for the theorist to work with in crafting theories: (1) problem statements, (2) thought trials, and (3) selection criteria.

Problem Statements. There is a fundamental difficulty in formulating problem statements for theory development research because “by their very nature the problems imposed on organizational theorists involve so many assumptions and such a mixture of accuracy and inaccuracy that virtually all conjectures and all selection criteria remain plausible and nothing gets rejected or highlighted” (Weick, 1989, p. 521).

To solve this problem, working on midrange theories, or theories that are “solutions to problems that contain a limited number of assumptions and considerable accuracy and detail in the problem specification” (Weick, 1989, p. 521), is favored. In other words, grand theories are overly complex in their possible assumptions and selection criteria. Midrange theories require clearer problem statements because they have closer boundaries. “These solutions are less generalizable because they define a more precise domain of action in the world.” (Storberg-Walker & Chermack, 2007, p. 507).

“Without clear and precise problem statements, attempts at theory building are misguided and vague. Two key conclusions can be distilled for theory builders using Weick’s approach: (1) problem statements must be detailed, clear, and precise; and (2) the nature of the problem can be highly practical or theoretical—both are valuable, though the climate of applied disciplines favors application and utility (Swanson, 2007b; Van de Ven, 2002).” (Storberg-Walker & Chermack, 2007, p. 507).

Thought Trials. Thought trials are different ways to address problem statements. “For Weick, the key to good theory building is to help the theorist generate diverse sets of possible solutions.” (Storberg-Walker & Chermack, 2007, p. 517). A lack of diverse thinking is thought to be directly related to the strong influence of preference and experience. To produce a better theory, the use of classification systems is recommended. “In organizational literature, these classification systems might include thought trials from varying philosophical perspectives (does a thought trial look different to a positivist or a social constructionist?), varying demographic perspectives (does a thought trial look different to the first-year employee of the organization or someone preparing to retire?), and so forth” (Storberg-Walker & Chermack, 2007, p. 344). The key point for theory builders following Weick’s approach is to stretch their thinking as widely as possible and entertain a diverse set of assumptions and possible solutions.

Selection Criteria. Theorists generally evaluate their thinking by posing questions to themselves (Storberg-Walker & Chermack, 2007). “The criterion that lies behind these questions incorporates considerable past experience with related problems. . . . The conjecture is being tested against the theorist’s prior experiences that has been edited down into assumptions” (Weick, 1989, pp. 524–525).

Biases and assumptions are clear issues in selection criteria, and they can create a bridge from the theorist to a more useful theory if they are carefully and explicitly examined. “Self-conscious manipulation of the selection process is the hallmark of theory construction. . . . The greater the number of diverse criteria applied to a conjecture, the higher the probability that those conjectures which are selected will result in good theory. If criteria are altered each time a conjecture is tested, few conjectures will be rejected and little understanding will cumulate” (Weick, 1989, p. 523). This amounts to making the problem fit the solution.

Highlighting the problem of theorist bias based on past experience is a worthy caution. Theorists should reflect on their ideas as they evolve. Specific solutions will vary in their appeal to a variety of theorists. Therefore, it is useful to be as forthcoming about biases as possible. Conceptualization work is part art, and theorists will do well to document their thinking and development processes as carefully as possible.

Qualitative Approach—Storberg-Walker’s Five-Component Approach

Storberg-Walker (2007) articulates an approach to conceptual development that consists of five components. The five components form more of a process for preparing to develop theory than for specifically generating the foundational theory concepts. The five components are (1) examine alternative perspectives and processes, (2) resolve paradigmatic issues, (3) resolve foundational theory issues, (4) resolve preliminary research design issues, and (5) identify and select the appropriate modeling process.

Examine Alternative Perspectives and Processes. This component is aimed at clarifying a variety of possible choices on precisely how to approach a theory development effort. Should I follow Dubin or Whetten? Make it up as I go? How could case study and grounded theory approaches be useful? What do I know about the domain of human activity, and what does that suggest? A theorist should examine a variety of approaches to the topic of interest and make a series of choices depending on such factors as purpose, experience, methodological exposure, and access.

Resolve Paradigm Issues. It is important to acknowledge the differences in assumptions that underlie varying approaches to theory development.

“Many theory scholars encourage multiparadigm theory-building research and/or multiple thought trials from different perspectives (Bourgeois, 1979; Gioia & Pitre, 1990; Jick, 1979; Pentland, 1999; Poole & Van de Ven, 1989; Weick, 1989, 1995).” (Storberg-Walker & Chermack, 2007, p. 517). However, experts in theory building do not often provide “explicit details about the cognitive decision-making processes of theory building, or the influences of assumptions and prior experience on those decisions” (Storberg-Walker & Chermack, 2007, p. 517).

Theory builders are advised to reflect on how different paradigms will impact the theory development and realize that choices here will have a strong influence on the output of the theory development effort as a whole.

Resolve Foundational Theory Issues. “Theorists are likely to have affinity to certain foundations over others; some theorists may view critical theory as a relevant foundation, while others may view human capital theory as more relevant” (Storberg-Walker & Chermack, 2007, p. 518). Strategies for working with alternative theories are recommended: (1) accept the paradox and use it constructively, (2) clarify misaligned propositions and define the connections among them, (3) require a time element, and (4) create an entirely new approach (Poole & Van de Ven, 1989, pp. 573–574).

Resolve Preliminary Research Design Issues. Theorists must think ahead to the eventual research design—even in the preliminary stages of identifying constructs. “In the long run, the best theory is only as good as its evidence” (Poole et al., 2000, p. 5). Theory builders should consider the best fits in terms of research design strategies that will eventually be required.

Select the Appropriate Modeling Process. The goal of conceptual development is to put forth a representation of the theory under construction. Whetten’s (2002) modeling-as-theorizing approach provides a clear process for achieving such a visual representation. “The graphical mapping process can be started at any time during the conceptual development phase . . . [and] does not have to come at the end of the process” (Storberg-Walker & Chermack, 2007, p. 518). Mind mapping, software-driven modeling, and other processes exist to help the theorist create a model, and each has advantages and disadvantages that are beyond our purposes here. The ultimate goal is to choose the modeling approach that is most beneficial to representing the proposed model.

The four conceptual development methods discussed have complementary elements and conflicting elements. Their pros and cons are summarized in Figure 4.2.

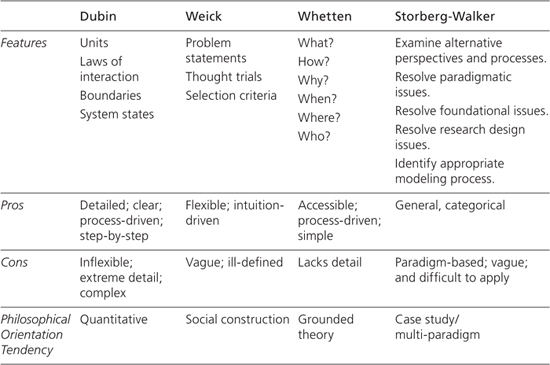

SPECIFIC THEORIZING TOOLS

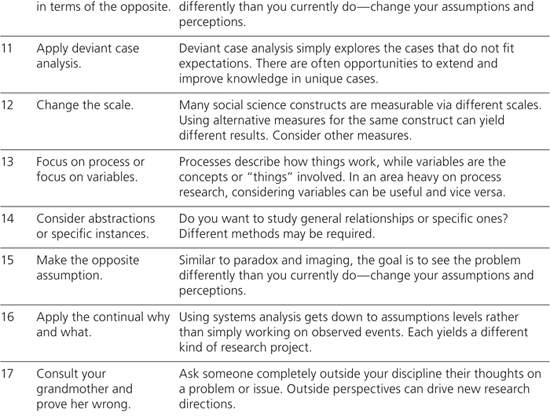

Twenty-six tools for generating ideas and getting the theory-building effort started have been identified (Jaccard & Jacoby, 2009). Of course, most of these tools make an assumption that the theorist is starting from scratch. The twenty-six tools are listed in Figure 4.3 along with the purpose and utility of each. Most of the tools are self-explanatory, but for further detail, see Jaccard and Jacoby (2009).

FIGURE 4.2 Four Processes for Conceptual Development

These tools are obviously useful in provoking ideas and deciding on a starting direction for theorizing. Most theorists have something in mind, or use some of the tools without making it explicit.

Summary of Existing Conceptual Development Methods

This chapter thus far has briefly presented four conceptual development methods and twenty-six tools for starting the theory-building process. Little has been written about how to integrate various approaches to conceptual development work. A core purpose of this book is to bring disparate views and approaches together in building a general method for theory building in applied disciplines. The next section describes a framework that integrates a variety of processes, tools, and approaches for working through the Conceptualize phase.

FIGURE 4.3 Tools for Starting a Theory-Building Project

THE CONCEPTUALIZE PHASE OF THEORY BUILDING

This section presents the Conceptualize phase of theory building in applied disciplines being advocated in this book. The approach is general enough to accommodate different philosophical orientations and include a variety of tools, and it is built on a process that makes it useful and applicable. The core steps in the Conceptualize phase are (1) identify the concepts, (2) organize the concepts, and (3) define the boundaries. Conceptual development is not necessarily a linear process, and theorists jump around among the steps. Theorists will almost always use a variety of the tools and approaches already described in this chapter. For example, a theorist might be confident in identifying the concepts in step 1, but when moving to organizing the concepts in step 2, she or he may realize that an important concept is missing—back to step 1. Rigorous and effective theory building requires multiple rounds of each step.

Step 1—Define the Concepts

The first step in the Conceptualize phase is to identify and define the concepts involved in the theory-building effort. These are the smaller components that will make up the theory in some domain of human activity. Major concepts are generally identified through a combination of experience, written experiences of experts, research publications, and practical problems. A thorough knowledge of the current status is required to identify a comprehensive group of concepts. A theorist may bounce back and forth between reading the literature of what is known and building concepts multiple times before setting on a final group and moving forward.

Imagine you want a new house. You see pictures and drawings of your dream house, you pay for that house and get ready to move in, and all you end up with are the pictures and the drawings! What an incredible shock. So it is with theory building: the conceptualization is just that—images, not yet the real thing. Unfortunately, the bulk of the “theory” in applied disciplines does not go beyond the attractive conceptualizations, and eager advocates quickly start selling it as complete. This in no way diminishes the importance of conceptualization; it is just that much more is needed in order to have a sound theory. For example, the best-selling book In Search of Excellence (Peters & Waterman, 1984) was based on looking closely at successful companies to determine what they were doing to be successful. This important input to conceptualization could have been the basis for building a sound theory of company excellence. Instead, the conceptualization—incomplete theory—was turned into a best-selling book, and the majority of companies that were deemed successful were shortly found to be unsuccessful. The only sure winners were Tom Peters and Bob Waterman, the book authors. The big losers were most likely the companies that tried the ideas in the book and ended up worse off than before they started.

Writing on problem statements as thought trials and selection criteria is useful in this step of theory building. Many of the twenty-six tools noted earlier, such as analyzing your own experiences and collecting practitioners’ rules of thumb, are good starting points. Gathering up the building blocks and the important ideas that are relevant to the theory is the first step in any theory-building effort.

Step 2—Organize the Concepts

Once the concepts have been identified, they must be organized. This means identifying and describing the relationships among the concepts. Here are some key questions to ask: Is there a time element involved? Does one concept occur before or after another? How do the concepts influence each other? Are the relationships known, predictable, and linear? Dubin wrote a very detailed and specific discussion of ways in which concepts can relate to each other that comprise a useful tool in this step—he called them “laws of interaction.” Drawing from Whetten, using sticky notes to arrange concepts in a systems diagram is also a very helpful approach. Experiment with a variety of tools and use what works. When relationships among the concepts become clear, a model begins to emerge.

One of the delicate things about theory building is that as the theorist continues to learn and ideas evolve and change, so does conceptual development work. It is appropriate to revisit how the concepts are related again and again. Eventually, theorists will settle on understandings or models that feel “right” or at least “right enough to move forward” and let the subsequent steps and phases determine the accuracy of the theorizing.

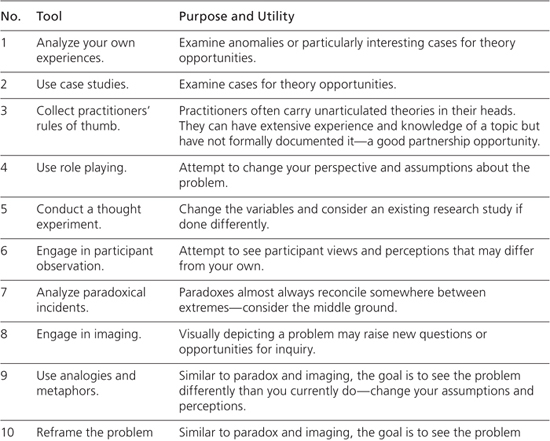

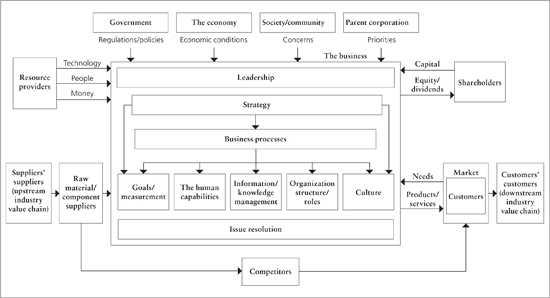

The Enterprise Model (Figure 4.4) was created to graphically portray how organizations work (Brache, 2002, p. 5).

This detailed graphic model provides a summary of the larger excellent description put forth by the author. The author’s logic and experience in presenting and explaining the enterprise model is mandatory and assists in moving the theory-building process ahead on this conceptualization. Obviously, you could create your own enterprise model without explaining its basis. And, you could begin “selling” your more shallow conceptualization, rather than continuing the theory-building effort on how organizations work.

FIGURE 4.4 The Enterprise Model

Source: Brache (2002); used with permission by Kepner-Tregoe.

Step 3—Define the Boundaries

The third step in the Conceptualize phase of theory building is to define the domain in which the proposed explanation is expected to apply. For example, approaches to team building in the United States may not be transferrable to Korea because of cultural differences. Planning practices in large corporations may be different from those in small companies. Boundaries locate the theory in the social world and require an understanding of factors that prevent or limit the utility of the theory in other places. The term boundaries seems most useful here and mirrors Dubin’s work. Boundaries do just that—they bound the theory to a particular context. The boundaries can be far and wide, or close and confined. The theorist had great freedom in setting the boundaries of the theory.

There is also a clear link between boundaries and the types of theories presented in Chapter 2. For example, the wider the boundaries are set, the more the theory will approach a grand theory. Bring them in closer and you have a midrange or local theory. Again, like the zoom lens on a camera, boundaries are critical to fleshing out details in the final “scene” of the theory.

In the realm of talking about organizations, people, and productivity, there are quite varied views about the boundaries of performance improvement. One is the psychological/educational view that focuses on the individual performer. Another is the economic/business view hinged on the financials. Systems/engineering, in contrast, targets process efficiency. Each of these has its own boundaries. When all three are put together, the boundaries expand, casting a wider net and more closely approaching a grand theory of performance improvement.

OUTPUTS OF THE CONCEPTUALIZE PHASE

Most scholars agree that the output of the Conceptualize phase is a model or set of linked concepts that explains a domain human activity. The model is almost always a visual representation of the proposed explanation. This is why systems mapping is highly useful in conceptual development. More specifically, when the conceptual development phase is complete, the theorist should be confident that a comprehensive set of concepts have been identified, their relationships have been described and clarified, and the boundaries of the emerging model have been set. Its accuracy is yet to be examined and creates the need for the subsequent phases of theory building.

SUMMARY OF THE STEPS

The Conceptualize phase of theory building in applied disciplines is challenging intellectual work. Motivation for starting conceptual development activity can come from a variety of places, including personal experiences, talking with practitioners, and existing research. Once established, the Conceptualize phase requires identifying the concepts, organizing them, and specifying the boundaries of the emerging model or set of organized ideas (see Figure 4.5).

FIGURE 4.5 Steps in the Conceptualize Phase of Theory Building in Applied Disciplines

QUALITY INDICATORS FOR THE CONCEPTUALIZE PHASE

Dubin (1978) provided a clear set of quality indicators, summarized here, for each substep of the Conceptualize phase. His criteria and indicators were precise and well described. No other authors have defined quality indicators for substeps within various approaches to theory development.

Criteria for Assessing the Defined Concepts

Dubin’s criteria for assessing the concepts selected for building a given theory are (1) rigor and exactness, (2) parsimony, and (3) logical consistency. Each of these criteria is described in further detail.

Rigor and Exactness. The rigor and exactness of the concepts of a theory refer to the kinds of concepts selected. Concepts that have variance are judged to be more exact than concepts that are simply present or not present. For example, a theory involving happiness would potentially be highly exact, because the concept of happiness varies considerably—a person could be mildly happy, content, very happy, or laughing out loud.

Parsimony. Parsimony in theory building refers to the fact that a minimum number of units is used to build the theory. Parsimony can be assessed by looking at the concepts involved and considering their removal one by one. If removing a concept does not change the model, it can stay removed and parsimony is increased.

Logical Consistency. The choice of concepts has immediate implications for the eventual testing or confirmation of the theory. The choice of units must have some logical basis in other theories, research, literature, or practice.

Criteria for Assessing the Organization of Concepts

According to Dubin (1978), parsimony is the single criteria for assessing the relationships among the concepts. Parsimony is established by utilizing the minimum number of proposed relationships to connect all of the concepts in the theory. While there is no fast rule for determining the appropriate number of relationships for any given theory, the same approach as with concepts can be used. Removing proposed relationships one by one and thinking through the implications for the theory can indicate where unnecessary hypothesized relationships might be.

Criteria for Assessing the Boundaries

Generalization and empirical testing are the two core criteria for assessing the boundaries of a theory (Dubin, 1978).

Generalization. The extent to which the theory will be generalizable depends on the size of the domain in which the theory is expected to operate (Dubin, 1978). A theory is made more generalizable by removing one or more boundary-determining criteria and expanding the boundaries to a wider domain.

Empirical Testing. An empirical test of the boundaries of a theory can produce three consequences: (1) the logically derived theoretical domain is confirmed as the empirical domain, (2) the empirical domain is greater than the logical theoretical domain, and (3) the theoretical domain is greater than the empirical domain (Dubin, 1978). In any case in which the two domains do not match, the boundary-determining criteria must be revisited and altered until a match is achieved.

Summary of Quality Indicators for the Conceptualize Phase

Dubin provided a very clear set of criteria for assessing progress in the early stages of theory building. His criteria are the only existing set of indicators specific to conceptual development work, and they are logical. Theorists can apply these criteria to conceptual development work on a new theory or on existing theories for improving them.

CONCLUSION

This chapter has examined the Conceptualize phase of the five-phase methodology for theory building in applied disciplines (see Figure 4.1). First, existing processes for conceptual development were presented in detail. These processes were compared with an eye toward practical tools for both theory-building novices and experts. A variety of other useful strategies for conceptual development were also introduced. The Conceptualize phase was defined with its three core steps: (1) define the concepts, (2) organize the concepts, and (3) define the boundaries that were advanced. These three steps can be used in revisiting existing theories or building theories from scratch. Finally, quality indicators for each of the three steps were described and clarified for practical use.