3

CONCEPTUAL STRUCTURES

We often use the word “concept” when we want a more exact equivalent for the word “idea.” Here are some examples of concepts: human being, cat, house, table, chair, computer, tree, painting, book, square, soft, red, unicorn, art, design, object, image, text, atom, universe, capitalism, racism, beauty, truth, sameness, and whole. As we can see from this list, concepts come in all shapes and sizes. They can be general or specific, concrete or abstract, natural or technological, artistic or scientific.

Concepts are the basic building blocks in human thinking; as such, they are highly flexible. They can apply to things that are real (e.g., people and cats) or imaginary (e.g., unicorns and fairies). They can help us to make distinctions between things that we observe in the world, such as tables and chairs, oak trees and elm trees, atoms and molecules. They can also aid us in distinguishing between quite abstract ideas, such as the differences between truth and falsity, appearance and reality, continuity and discontinuity.

We clearly need concepts to help us think about, organize, and understand the world. Yet we frequently fail to realize just how little we know about the subtleties and implications of the concepts that we use.

Consider the following questions:

Is the Harley-Davidson an American design?

Is the Harley-Davidson a good design? What is design?

The first question appears to be answerable on the basis of certain facts. Either it is an American design or it isn’t. Or maybe it is partly American. The second question appears to be answerable on the basis of certain judgments that we might make about the Harley-Davidson: namely, whether we regard it as having qualities or features that, perhaps more generally, make a design good. The third question is conceptual; it requires us to say something about design and what it consists of.

This means that we can categorize our questions as follows:

Is the Harley-Davidson an American design? (Factual Question)

Is the Harley-Davidson a good design? (Value Question) What is design? (Conceptual Question)

Notice that in order to answer the first two questions we have to be able to answer the third question. In the first instance, this is because we can hardly judge whether the Harley-Davidson is an American design unless we are sure that it is actually a piece of design and not something else (say, a work of art). In the second instance, this is because we cannot know whether the Harley-Davidson is a good design without being able to say what it is like in terms of design qualities; qualities such as (say) functionality, beauty, simplicity, efficiency, and utility. So conceptual questions are vital to any understanding of the meanings of the questions that we ask and the answers that we give in reply.

While individual concepts such as design often need to be carefully articulated for us to understand a particular issue in a precise way, concepts are not always to be understood in isolation; they often form links and relationships with one another. Indeed, pairs of opposing concepts provide a particularly useful structure for study in semiotics as they assist us in interpreting and exposing the underlying features of different human practices. For example, take the way in which we eat. The practice of eating is given a structure by some simple distinctions that are to be found in various cultures. Thus, in talking and thinking about food it is often important to recognize the conceptual difference between that which is raw as opposed to cooked, edible as opposed to inedible, and native as opposed to foreign. It is through these pairs of opposing concepts (i.e., raw/ cooked, edible/inedible, native/foreign) that we come to appreciate the structures that are often imposed on the way we eat.

The same can be said for other human activities. Take religion. Religion is given a structure via a different set of contrasting concepts. This time the concepts include humans and gods, life and death, the sacred and the profane, and good and evil. Once again, these concepts help in clarifying and making sense of not just some religious practices, but perhaps all of them. Also, such concepts help in understanding how religions need opposing forces for them to make sense to their believers.

The same approach can also be taken to clothing. The way that we think about clothing can be understood in terms of garments worn by men and women; by the distinction between formal wear and casual wear; and via the contrast between parts of the body that a given culture thinks should be covered as opposed to uncovered. These pairs of concepts (men/women, formal/casual, covered/uncovered) help to give sense to what might at first appear to be diverse and inexplicable sets of cultural phenomena in the area of fashion.

Discussions of various opposing pairs of concepts that we find in the areas of food, religion, and fashion are legion in the subject of semiotics. However, there are also pairs of more abstract philosophical concepts that apply to all manner of disciplines, subjects, and cultures that are not discussed so often.

These concepts include: truth and falsity, sameness and difference, wholes and parts, subjectivity and objectivity, appearance and reality, continuity and discontinuity, sense and reference, meaningful and meaningless, and problem and solution. In this chapter we will focus on these concepts because, as we shall see, they govern different kinds of human thinking at a fundamental level.

TRUTH AND FALSITY

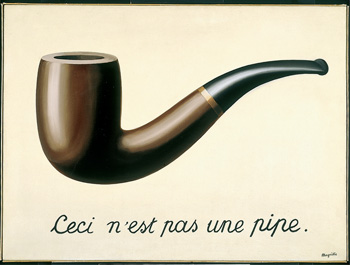

IS THERE A PIPE IN THIS PAINTING?

In his famous picture The Betrayal of Images (“This is not a pipe”) (1928–29), the Belgian artist René Magritte has written below an image of a pipe “This is not a pipe” in French. But if this is not a pipe, then what is it? One obvious answer is that it is a painting of a pipe. A painting of a pipe is not a pipe, but only a way of representing a pipe. The same could be said of the word “pipe.” The word “pipe” is not a pipe either, but only a word that has the power to stand for the presence (or absence) of a pipe. Magritte’s picture raises questions about the ability of images and language to represent or misrepresent the world itself. Through this picture we come to realize that truth and falsity are stranger concepts than we thought.

Truth and falsity are sufficiently curious that they cannot always be determined. This is particularly so in the world of fiction. Consider the following sentence: “Hamlet had a wart on his nose.” Surely this sentence, like the painting by Magritte, represents the truth or it does not. So is it true or false that Hamlet had a wart on his nose? The problem that presents itself here is that nowhere in Shakespeare’s play does it tell us whether Hamlet did or did not have a wart on his nose. Perhaps he did, or perhaps he didn’t. We just don’t know, and maybe Shakespeare himself did not know either. What this means is that there are some instances (and fiction is the most notable case) where talking of truth and falsity may make no sense.

If painting and other forms of representation are like the world of fiction then it may not be wise to talk about them in terms of truth and falsity. That said, however, it is still true to say that this image looks like a pipe (and it is false to say that it doesn’t look like a pipe). The reason is simple. If it didn’t look like a pipe it would be impossible to teach others—for example, children—that it did look like a pipe.

SAMENESS AND DIFFERENCE

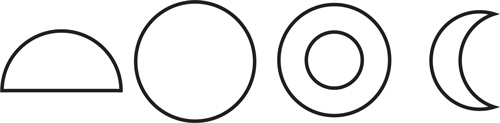

WHICH SHAPE IS DIFFERENT FROM THE REST?

There is actually no real reason for thinking one shape is different from the rest. It is only a matter of how we choose to perceive these shapes that may make us say that one is different from the others. For instance:

The first shape is the only one with a straight line.

The second shape is the only one that is truly basic.

The third shape is the only one that consists of two separate lines.

The fourth shape is the only one that looks as if it represents a familiar object (i.e., the moon).

Spotting differences is sometimes easy. At other times it is more difficult. Counterfeits, decoys, art forgeries, design replicas, fake currency, photocopies, reproductions, facsimiles, camouflage, instant replays, disguises, impersonators, identical twins, and cloning are all things that raise questions for us about sameness and difference. (They also help to highlight the difference between something real and something that is merely a copy.)

There are two basic sorts of difference. One is a difference in kind, while the other is a difference in degree. Differences in kind are based on the fundamental sort of thing that we are talking about. For instance, while a person might look the same as a very realistic showroom dummy, these are fundamentally different kinds of thing. On the other hand, differences of degree occur when there are variations between things that may be very similar underneath. For example, the difference between a mountain and a molehill is only one of degree (nevertheless, the difference here is still large). There is also only a difference in degree between a genuine dollar bill and a forged one (this, though, may involve a very small difference).

The curious thing about sameness is that it is not as absolute as one might think. That is why we often need to ask: “In what respect is x the same as y? Is it the same in respect of its shape, texture, color, tone, material, use?” After all, it is only when x is the same as y in every respect that we don’t really have any differences to speak of.

WHOLES AND PARTS

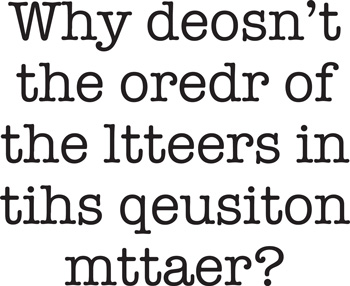

CAN YOU READ THIS?

The oredr of the ltteers deosn’t mttaer bcuseae we do not hvae to raed ervey lteter bferoe we can raed the wlohe wrod. The mian tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer are in the rghit pclae. The oethr ltteers can be in a toatl mdudle and you can sitll raed the snetnece wouthit a porbelm.

If we tend to see the whole word before we see its parts when we read, then what happens when we look at an image? We might assume that a portrait can only be a true likeness if the various parts of the face are considered carefully in relation to the whole. But some of Picasso’s portraits demonstrate that even if you jumble up and distort the details of a face it can remain a good likeness. So maybe the look of the whole face is more important than the exact arrangement of its parts in portraiture.

Underlying these points about parts and wholes is a more general issue, which concerns the philosophical one of when we count something as a part and when we count it as a whole. The iris is part of a whole eye. An eye is part of a whole head. A head is part of a whole person. A person is part of a whole society. So eyes, heads, and persons are both wholes and parts at the same time. What we see as a whole and what as a part, then, may depend on what we are trying to explain. If we want to understand how the eye works we will miss something if we look only at the iris. Similarly, we will leave something out if we try only to understand the eye in relation to the whole head. What is important is that we engage with the thing we are trying to explain at the right level. In doing this, though, we should not forget that the complexities of the world result from the fact that we can always divide a thing into its component parts or else look for other things that link with it to form a larger whole.

SUBJECTIVITY AND OBJECTIVITY

DO YOU SEE THE COLOR RED IN THE SAME WAY AS OTHERS SEE IT?

Some things appear to have a quality that is like nothing else:

The taste of coffee.

The smell of a rose.

The feel of fine-grained sand.

The sound of a bird singing.

The look of the color red.

The qualities of our experience seem to be indefinable in some ways. For example, no matter how much we are told about the science of color (i.e., about wavelength, purity, and intensity, the color-processing parts of the brain, different techniques of stimulation and problems such as color blindness), we cannot say what it is like to have the experience of it. We can only say what the experience is like by having it. In this sense the experience of color appears to be subjective (and personal) rather than objective (and scientific). (As an experiment, ask yourself whether, if you had never had the experience, you could imagine what it would be like to taste coffee, smell a rose, feel sand, hear a bird sing, or see the color red.)

Though there is the subjective side to our experience of these qualities, there is also an objective side that can be tested by various scientific methods. The objective tests for color do not concern what it is like to have the experience so much as the facts concerning what is perceived. These tests are particularly advanced in physiology and psychology. For example, there are tests that will help us to discover whether color is variable or constant under a variety of viewing conditions, and how the colors that we perceive are dependent on the context in which they are placed (e.g., a color may vary when it is placed next to other colors that are either similar or contrasting). All of these tests reveal something about the physiology and psychology of our perception. However, what they do not reveal—and this is the important point for semiotics—is just what these various colors (and other sensory qualities) actually mean to us.

APPEARANCE AND REALITY

DOES THIS BATTLE LOOK REAL?

It is often said that the quasi-mathematical technique of linear perspective is the best system for representing visual reality. Developed, some have thought, by Filippo Brunelleschi, the early systems of perspective employed a series of lines that appeared to meet on the horizon at a single vanishing point. The results that were derived by using this system seemed real because they gave the impression of spatial recession and pictorial depth.

The fixed perspectival point of view that is offered to the viewer using this system is illustrated on the previous page in the work of Paolo Uccello in Battle of San Romano (c. 1435–60). This picture, by using the contrivance of lances placed on the ground, gives the viewer a series of visual cues that leads the eye from pictorial elements in the foreground of the picture (such as the central figure of Niccolò da Tolentino) to the background of the cultivated landscape with its tiny fighting figures. But does this device make the picture real, in the sense that we are presented with pictorial equivalents to the visual cues we find in “normal” perception?

There are various problems with Uccello’s picture as regards its verisimilitude. One problem is that the fixed viewpoint that Uccello gives us does not take account of the fact that in reality the eye is constantly moving in order to see objects in space. Another problem is that we see the world with two eyes, so creating a better representation of reality should actually involve a perspectival system that uses two vanishing points on the horizon so as to give more accurate up-hill and down-dale effects. A final problem is that perspective cannot be a substitute for the measurement of the objects that we see in space.

What Uccello’s painting shows is that perspective, while it gives the impression of reality, is one pictorial contrivance that artists may find more or less useful in making images of the world. (Certain formal qualities such as line, tone, texture, and color can, of course, also contribute toward making a picture look realistic.) And even if there are some real-seeming elements to the picture that derive from the way perspective is used, it is still clear that nobody would mistake this for a real battle.

CONTINUITY AND DISCONTINUITY

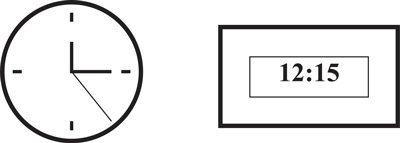

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THESE TWO TIMEPIECES?

One answer is that the two timepieces give different representations of continuity and discontinuity. The first thing to note is that the watch face on the left represents time in analog form, whereas the clock on the right represents it in digital form. This creates two different effects. With the watch face we can see time passing as the hour, minute, and second hands move round. Moreover, if we are timing something we may also see how much time has been used up and how much is left. However, with the clock there are only a number of quite sudden changes that happen. With a numerical display such as this we are only able to see exactly what time it is now.

The basic difference between the two forms of representation is that the analog form of time (i.e., the watch face) gives more of a sense of a continuum as the present is represented as having a relationship to the past and the future. With the digital form of time (i.e., the clock) there is an exact representation of the time in the present moment, but as there is a jump when the numbers change time can appear to be composed of units that seem discontinuous.

In general, analog signs create relationships that are graded on a continuum. Examples are things that have a more/less quality, such as: visual images, physical gestures, facial expressions, bodily movements, textures, tastes, and smells. These signs have a richness, complexity, and continuity that cannot easily be expressed in another medium. On the other hand, digital signs have an either/or quality that can seem discontinuous because the categories used are unitized. Examples are things like the following conceptual oppositions: zero or one, off and on, this or that, black and white, light and dark, alive or dead. Notice in all of this, though, that analog codes that have a flow, such as music, can sometimes be represented in digital form (e.g., on a compact disc).

SENSE AND REFERENCE

WHAT DO YOU NOTICE ABOUT THE MAN DRINKING CHAMPAGNE?

In asking about “the man drinking champagne” it is easy to give the impression that we are referring to someone in a straightforward way. But perhaps the person that we think is the man drinking the champagne is, in fact, a woman. In this case there may be no person who is drinking champagne. Alternatively, it might be that the phrase “the man drinking champagne” is inappropriate because the two people in question are just holding their glasses, but not actually drinking champagne from them. Another possibility is that we might have picked out the wrong person in using the phrase “the man drinking champagne” because the man drinking champagne is using a beer glass (while his friend, who has the champagne glass, is actually drinking beer from it). Lastly, we might say that there is no man drinking champagne because both men are drinking a sparkling wine that is not champagne. One lesson here, then, is that just because we want to refer to something or someone, does not always ensure that we will succeed.

Reference is intriguing because you can refer to the same person or object in different ways. When I say “the man drinking champagne” I intend to pick out a certain individual, but if I find that you don’t know which person I mean then I could add, “the man with the red jacket.” These descriptions, though different in sense, could have the same reference. The same point about coreferring terms can be made with the example of “the morning star” and “the evening star.” The phrases “the morning star” and “the evening star” clearly have different senses (or meanings), even though they refer to the same entity, namely Venus. Yet one might suddenly discover that the planet that I am referring to in one way (as “the morning star”) is the very same as the planet you are referring to in a quite different way (as “the evening star”).

The issues just discussed may make us consider how shifts in meaning or reference can serve to undermine or compromise our ability to communicate clearly and unambiguously with one another about all manner of things that we take for granted in the world.

MEANINGFUL AND MEANINGLESS

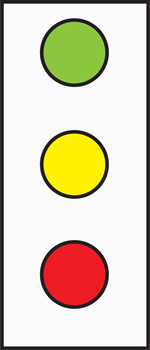

DO THESE TRAFFIC LIGHTS MAKE SENSE?

In the traffic light system that is used in many parts of the world we assign a meaning to each of three colored lights: red, yellow, and green. For drivers using this system the lights have the following meanings:

Signifiers: | Red | Yellow | Green |

Signifieds: | Stop | Caution | Go |

What these lights mean can seem obvious if you are already familiar with them. Their meanings, though, depend on a number of underlying assumptions. The first is that we each have the ability to distinguish the color concepts red, yellow, and green from one another (this is not an assumption that we might want to make about people that are color blind). The second is that we understand the meaning that each colored light has in the cultures that employ this system (and this is a matter of an established convention that other cultures may not immediately appreciate). The third is that we understand how and why the lights themselves form part of a larger system of road signs (and this, again, depends on specific cultural knowledge that one might have about the country one is driving in).

The meaning of each light is arbitrary if only in the sense that the following combination could still have worked to control traffic had it been agreed upon by the culture in question:

Signifiers: | Yellow | Green | Red |

Signifieds: | Stop | Caution | Go |

The reason this alternative system could work equally well (and be equally meaningful) is, first, that each color is visually distinct and, secondly, that each color can be assigned a specific meaning within the traffic light system.

Now think what would happen if traffic lights were structured using the following colors:

Signifiers: | Orange | Red/Orange | Red |

Signifieds: | Stop | Caution | Go |

This would result in confusion, not because the lights are set out in the wrong way, and not because the lights would be intrinsically meaningless, but because human beings find it hard to see the difference between orange and red/orange and red and red/orange by using the concepts that they have. And this would result in confusion about their meaning, even if it did not render them meaningless.

PROBLEM AND SOLUTION

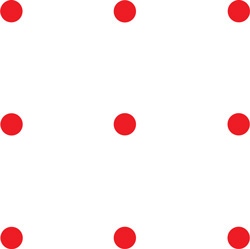

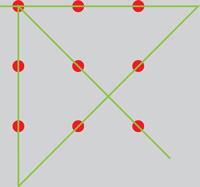

CAN YOU CROSS THROUGH ALL NINE DOTS USING ONLY FOUR STRAIGHT LINES WITHOUT LIFTING YOUR PEN FROM THE PAPER?

The nine-dot problem is often used to illustrate how our thinking can get stuck. This happens because the tendency is to think within the box shape that the nine dots seem to create. However, when you step outside this constraint a solution suggests itself. One solution is given below:

Once this solution has been seen the tendency is to stop searching for alternatives. Yet there are many others. You could draw through the dots with a pencil that has a tip wider than the box shape itself. You could cut the dots up and put them in a line and then draw through them. You could fold the paper so that you have a small square with all the dots lined up behind one another and push a pencil through them. In other words, each problem may have many solutions.

When we face a difficult problem we often search long and hard for a solution. The history of pictorial representation demonstrates this. Painters thought for a long time that pictures could develop in such a way as to become more true to life. But the problem with any representational medium—whether paint or language— is that it can only stand in different ways (using different signs) for the things that are represented. And because paint and language are not (and can never be) reality they will always fall short of reality. Thus the underlying assumption that we should search for the perfect medium of representation that can mirror reality must be mistaken.

One overall philosophical difficulty we face is that while some problems have one solution and others have many solutions, some problems have no solutions, and some problems are not even problems. The problem, then, is often in telling what sort of problem we have.