6

MATTERS OF INTERPRETATION

How would you interpret the following message: 10–2–4? As it stands, the message is almost impossible to understand. That is because we have no idea about how, where, why, or for what purpose it was made. Once you know its context, though, the meaning of the message is clear. This is the information you need to interpret the 10–2–4 message correctly.

The numbers 10–2–4 first appeared on the bottles and advertising of the Dr Pepper drink. They were based on a piece of research into fatigue that was conducted in 1927; this suggested that people’s energy levels tended to drop to their lowest point at 10.30am, 2.30pm, and 4.30pm. As the Dr Pepper drink is supposed to give you energy, this research was meant to provide a reason for consuming the drink three times a day—which some people did. The company that made the drink encouraged people to discover the correct interpretation of the message for themselves in the hope that this effort would make the message more palatable.

The obvious problem with a message like this is that we need to understand the code that is being used to decipher it. In this instance, it is quite difficult to discover what the code is. That is not to say, however, that all codes that we use in interpreting messages are equally hard to understand. In fact, the difference between messages like this, and most of the everyday messages that we encounter, is simply that the latter happen to be coded in a more recognizable and user-friendly form. In other words, all messages are coded, and all codes can be decoded (in principle, even if not always in practice), but some are easier to decode than others due to their familiarity. For example, warning signs, health advice posters, simple instruction booklets, food recipes, documentary photography, and news programs are seemingly straightforward to interpret because they contain messages that use codes with which we are familiar. This makes decoding them appear easy. In contrast, secret handshakes, cryptic crossword puzzles, the language and slang of youth cultures, academic jargon, police radio codes, and military signals are not easy to interpret because these messages make use of codes that are deliberately obscure. Decoding, in these cases, seems much more difficult.

Usually, when a message is difficult to interpret, we look beneath the surface for the deep structures, unconscious foundations, hidden symbols, and underlying patterns that may support it. If a message seems transparent, however, we tend not to look for these things. Part of the job of a semiotician, then, is to reveal those factors that provide and sustain the background for the various forms of communication in which we are interested, whether they seem difficult or easy to understand on the surface. Semioticians will do this because, by engaging in various forms of analysis, they may be able to expose just how much background information is needed for us to understand messages of all kinds, even those that appear on the surface to be wholly transparent.

All of this makes it seem as though interpretation has correctness as its ultimate aim. Certainly, this often is the ultimate aim. It almost goes without saying that we should want to avoid misunderstandings, misconceptions, misjudgments, forms of misinformation, muddles, slip-ups, oversights, and mistakes. However, given that we are subject to all kinds of personal, social, cultural, and historical biases, this is frequently difficult to achieve. For this reason, it is important for us to dwell on the kinds of codes, conceptions, and conventions that we are using to interpret any message that is at hand. That way, we may become more aware of the assumptions, presuppositions, prejudices, and forms of partiality that we could be unconsciously entertaining due to any divergence that exists in our experiences or ways of thinking. There is often much more to such things as warning signs, health advice posters, simple instruction booklets, food recipes, documentary photography, and news programs than we may initially think in terms of the meaning that is being communicated. A warning sign about the speed limits on a certain road may reflect a political decision to attempt to influence the number of traffic accidents, while a health advice poster about sexual activity may reflect a deeper bias within a certain society about controlling the “moral” behavior of its citizens.

When it comes to the interpretation of signs, our understanding is mediated through the various concepts and conceptions we have of different kinds of subject matter; by the various connotations and denotations that objects, images, and texts can have; via the arrangements and laws for constructing cultural phenomena (langue), as well as the particular instances that are constructed by those arrangements and laws (parole); by the codes we have for combining different things to create an ordered sequence of signs (syntagm), and for making appropriate substitutions in that sequence (paradigm); through the distinction between individual tokens, and generic types, of thing; by the rules that we follow for using objects, images, and texts successfully; via classifications that allow us to categorize and organize things; through the conventions that draw on common forms of knowledge; and by the ways that we have devised for understanding (and misunderstanding) that which we think we know.

What this chapter will show is that interpretation, in theory, can go on forever. This is because we can always take things in new and different ways—and we frequently do so. After all, part of the perennial qualities of authors such as Shakespeare, composers such as Bach, painters such as Leonardo, and sculptors such as Michelangelo is that they can, and will, be subject to new interpretations as history unfolds. In practice, though, we would do well to remember that interpretation ends when we need to arrive at conclusions or when we have reached a situation where action is required.

CONCEPTS AND CONCEPTIONS

CAN YOU TELL THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN OAK TREES AND ELM TREES?

Different kinds of information, as well as different amounts of information, can inform our concepts. Take the concepts “oak” and “elm.” Suppose we are talking to a neighbor about the trees in our garden. We mention that we have had our oaks and elms pruned during the year. Perhaps the neighbor understands what is being said even though they cannot, with any degree of certainty, identify which tree is which. In this case, the information that our neighbor has coded into the concepts “oak” and “elm” just happen to be of a rather general treelike kind.

Now imagine that there is a second neighbor who is good at distinguishing oaks from elms. This neighbor can tell the difference between the two kinds of tree by how the trunks look, by the characteristics of the leaves, and by the size and shape of each canopy. This neighbor has an understanding of oaks and elms that includes a sound recognitional ability, and so although they are using the same concepts as the first neighbor, their conception of (or thoughts about) the concepts “oak” and “elm” are rather more sophisticated.

Suppose that there is also a third neighbor. This neighbor is an expert in biology. He knows how to recognize the trees in question, but he also knows that oak trees belong to the genus Quercus and the family Fagaceae and that elm trees belong to the genus Ulmus and the family Ulmaceae. As he has a scientific knowledge of oaks and elms his understanding is even more sophisticated than those of the previous neighbors. (Notice, though, that someone may have a general grasp of what oaks and elms are and be able to give a biological description of them, without necessarily having an ability to recognize them. For instance, a person who lives in a country where oaks and elms do not grow may not be able to recognize them.)

If people can have different information coded into the concepts that they use, then their conceptions (or thoughts) about those concepts will tend to differ. That is why ordinary folk, gardeners, and biologists may have quite different thoughts about, and interpretations of, oaks and elms even though they may talk to each other using the very same concepts.

CONNOTATION AND DENOTATION

IS THIS EXCLAMATION AMBIGUOUS?

When we speak it is important for the purposes of interpretation to know not just what is said (denotation) but how it is said (connotation). Suppose I am asked what I think about a particular text and I reply, “What nice handwriting!” This comment has a single denotation. It denotes the quality of the handwriting. Yet it may have a literal connotation (i.e., the person does really have nice handwriting) or a nonliteral connotation (i.e., that nice handwriting is about the only thing they have). Put another way, the connotation of the words “What nice handwriting!” depends very specifically on the context in question and the way in which the words are uttered.

To understand connotation and denotation in images, consider how two photographs might be taken of the same person at the same time from the same position. Suppose that the first photograph taken is in color with a soft focus and gentle contrasts. Now imagine that the second photograph taken is in black-and-white with a clear focus and strong contrasts. Each of the two photographs has the same denotation (i.e., the same things are represented), but is different in terms of connotation (i.e., they don’t have the same meaning). This is because denotation is concerned with what is photographed, while connotation is concerned with how it is photographed.

The distinction between connotation and denotation applies equally to objects. Take clothes. When we wear clothes it is important not just what we wear (denotation) but how we wear them (connotation). You can wear exactly the same clothes on two occasions (denotation) but they can mean something different if the occasions on which, and the purposes for which, they are worn are dissimilar (connotation). For instance, there is a considerable difference between wearing a police uniform as a genuine police officer and wearing it as fancy dress to a party. In the first instance, the police uniform may be worn in an uptight, formal fashion to establish authority. In the second instance, it may be worn in a relaxed, informal fashion to create amusement.

LANGUE AND PAROLE

WHAT IS WRONG WITH THIS MENU?

“Langue” and “parole” are technical terms in semiotics. “Langue” denotes the code (or structure, system, plan, construction, or set of rules) for the object, image, or text that is being used, whereas “parole” is about the particular instance of use that has been produced. Langue, then, provides the organizational means for each individual example of parole. Here are some examples:

Langue | Parole |

The arrangement of menus | A particular menu |

The format of a postcard | An individual postcard |

The structure of a novel | A particular novel |

The construction of e-mail | An individual e-mail |

The design of gift catalogs | A particular gift catalog |

The organization of TV schedules | A specific TV schedule |

The layout of tickets | A given airplane ticket |

The composition of paintings | An individual painting |

The regulations for wills | A particular will |

The rules of grammar | A given sentence |

The conventions of spoken utterances | A spoken utterance |

The form of a conversation | A certain conversation |

The language of film | A particular film |

As we can see, each code, structure, system, plan, construction, or set of rules (langue) does something to regulate, and give meaning to, its use in a particular instance (parole).

For example, an individual menu (parole) will conform to the general arrangement that menus tend to have in terms of layout and structure (langue). In order for a menu to function there will need to be a choice from a selection of interchangeable parts (e.g., from different kinds of starters, entrées, and desserts), which may then be combined to reflect such things as taste, fashion, practicality, and fit with certain social occasions and norms. (Think here of the design of a menu for a formal dinner as opposed to a birthday party.)

Menus, we might say, have a grammar that reflects the practices of eating. But notice that the standard arrangement of a menu may need to be changed in certain circumstances. Such a change would be required if you tried to live your life backward. In such a case you might want a menu like the one on the previous page.

COMBINATIONS AND SUBSTITUTIONS

IS IT ODD TO COMBINE CLOTHES IN THIS WAY?

In the images on the previous page there is a mismatch between the clothes and the hats. Social rules dictate that the top hat should be combined with the suit and the cricket cap should be combined with the cricketing oufit. This is not to say that you cannot combine clothes in the way shown, it is just that doing so will tend to create a comic effect, which is fine if this is the effect that the wearer wants to achieve.

Different societies use different cultural codes to regulate how clothes are combined. These codes may reflect preexisting canons of taste (e.g., “Ought I to wear red pants with green shoes?”), social demands (e.g., “Which group will I identify myself with by wearing a bandana?”), or ritual episodes (e.g., “How should I dress if I am going to a job interview as opposed to a sports event?”).

When we put clothes together to form an ensemble we call this a “syntagm.” A syntagm is any combination of things that conform to a specified set of social rules.

That is why, when we notice the inappropriateness of the combination of clothes that a friend has assembled for the purpose of going to a funeral, we may say: “Your somber shirt goes with this dark pair of pants, but not with this jolly pair of yellow socks, which will undermine the serious mood of the event.”

In addition to the rules of combination that form a syntagm, there are rules of substitution that form what is called a “paradigm.” A paradigm is created by the social rules that dictate when one thing can be substituted, added, or removed in a certain system without that system being undermined overall. Take clothes as our example once again. If we wish to dress casually then we can substitute different kinds of T-shirt with the one we are wearing without it necessarily affecting the overall casual clothing “syntagm” that we are trying to create. What we cannot do is substitute a formal dress shirt for this T-shirt, as this will undermine the casual effect that is intended.

TOKENS AND TYPES

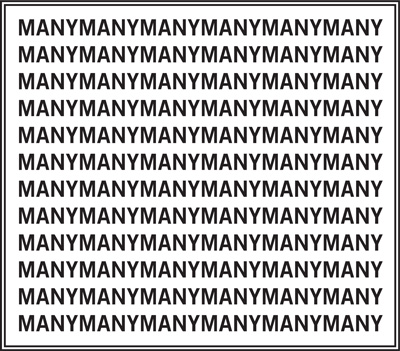

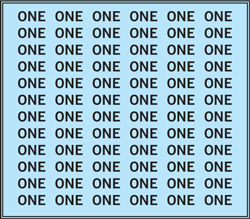

HOW MANY WORDS ARE THERE IN THIS BOX?

How you interpret these questions depends on whether you think of the words as tokens or types. The number of tokens is the same as the number of words in the box. In the first box there are 72 tokens of the word “many.” In the second box there are 72 tokens of the word “one.” But in each box there is only one word of the same type. In the first box, “many” is the type of word that is being used. And in the second box “one” is the type of word that is being used. Notice here that different tokens of the same type of word may be interpreted in different ways according to how they are produced. Here are three tokens of the same type of word, each with a different emphasis: smell, Smell, SMELL. In this instance, each token may be interpreted in a different way because of the variation in emphasis that it has been given.

The token and type distinction can be applied to objects and images just as much as to texts. A particular bronze sculpture can exist as a token object in a specific museum. But if we know that more than one bronze sculpture has been cast from the original mold then we might expect to encounter bronze sculptures of exactly the same type in other places. Similarly, a print (e.g., an etching) can exist as a series of tokens if there is a printed edition of it. Each token print (given that it is printed from the same plate) is an example of the same type. The same distinction between tokens and types holds for replicas (e.g., decorative moldings), duplicates (e.g., wills), facsimiles (e.g., manuscripts), carbon copies (e.g., letters), reproductions (e.g., furniture), reprintings (e.g., books), and models (e.g., cars).

Somewhat surprisingly, what holds for objects, images, and texts holds also for thoughts. If two people say the words “I like semiotics,” they will each be uttering a different individual token of the sentence, but they will be having a thought of the same type.

RULE-FOLLOWING

WHAT ARE THE RULES FOR USING THIS CORKSCREW?

When faced with everyday objects we follow the rules that we think will allow us to use them successfully. The rules for using a corkscrew are simple enough. They are:

1. Grasp the handle of the corkscrew firmly and insert the screw thread into the bottle by twisting it in a clockwise direction.

2. Once the thread has been fully inserted into the cork, draw slowly on the handle of the corkscrew while maintaining a tight grip on the bottle with your other hand until the cork is released.

These rules are fine for a right-handed person using a right-handed corkscrew. However, they are wrong, or at least misleading, for a right-handed person who is attempting to use a left-handed corkscrew. This is because the thread on a left-handed corkscrew (like the one shown on the previous page) goes in the opposite direction. To use a left-handed corkscrew successfully you need to turn it in an anticlockwise direction.

What we should learn from the example of the left-handed corkscrew is just how much we rely on interpreting certain rules correctly, and just how much our success in doing so depends on hidden assumptions, social customs, cultural norms, kinds of conformity, forms of training, traditions of use, and educated propensities. The rules that we use are important to reflect upon directly because we often fail to see just how much our behavior and our actions depend upon them. Indeed, every day we are faced with objects that have tacit instructions for their use, images that have masked codes for their interpretation, and texts that obey the, often hidden, regulations that are set by the institution of language. In failing to notice these rules we also fail to see the opportunities for questioning them and thereby creating new codes and forms of meaning.

CONVENTIONS

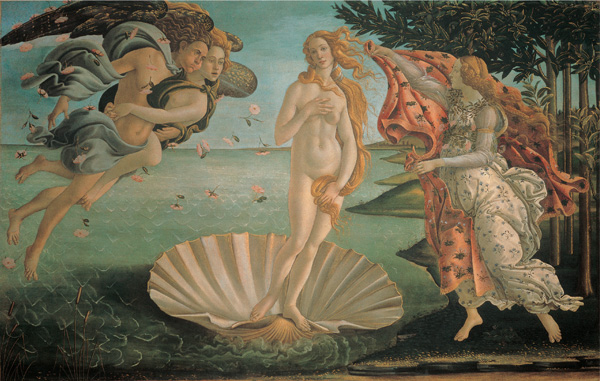

DOES THE WOMAN IN THE CENTER OF THIS PICTURE LOOK REAL?

In Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (c. 1485–86) we see a woman about to step on to the seashore from a giant shell. There is something odd about this figure. The elongation of her neck, the curious sloping of her shoulders, the awkwardness of her arms and legs, and the sheer length of her body all go to make her seem unnatural in some way. There is actually an obvious explanation for these anatomical peculiarities: this is not a real woman. It is the goddess of love and beauty, Venus. So what is being represented is an ideal of beauty. That is why Botticelli uses elongation and distortion in the picture. The only difficulty is that to interpret this message you have to understand the conventions that are being used. Conventions are agreed systems of understanding that allow us to interpret what is happening. In this instance, you need to understand that by elongating the human body—a convention still to be found in contemporary fashion drawing—Botticelli idealizes the female form in order to make it more beautiful.

Conventions are often so much part of a culture that we fail to realize that the codes they use are not always transparent to cultures other than our own. Just how much we assume about the transparency of certain common codes can be seen from a plaque that was put on the Pioneer F spacecraft, a probe that was sent into space in the 1970s. The plaque had a line drawing of two human beings, a man and a woman. Its purpose was to communicate the presence of human life on earth in such a simple way that any intelligent form of life that might happen to come across it in space would be able to interpret it immediately. However, in order to read the intended message any alien form of life would have to understand that the lines stand for contours, that the figures are in perspective, and that the right hand of the man (which is raised) is supposed to signify a greeting. Yet even supposing that the intended audience of aliens had eyes, which in itself is a big assumption, it is still quite unclear that the message could be understood without the requisite knowledge of the conventions of pictorial representation that have, unwittingly, been supposed to be wholly transparent by those who made the drawing.

CLASSIFICATIONS

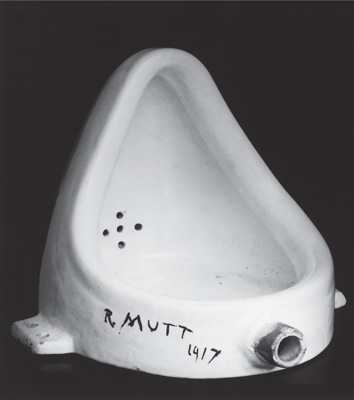

IS THIS ART?

The way we classify things is important. The botanical sciences would never have made progress had it not been for the orderly cataloging of flora. Libraries and museums would not have grown without the highly developed systems that were devised for organizing and arranging their collections. And governments of all periods would not have been able to function without some way of categorizing and grading information into that which is, and that which is not, confidential.

The need for classification is clearly evident from many human fields. Progress itself seems to depend on it. However, while certain things seem to be amenable to classification, others do not. For instance, what sorts of things should we classify as art? Here are some possible responses:

1. All the things that people are generally disposed to call “art.”

2. All the things that connoisseurs of art call “art.”

3. All the things that I call “art.”

4. All the things that are displayed in art galleries with the purpose of being viewed as art.

5. All the things that are called “art” by artists.

6. All the things that common sense tells us are art.

7. All the things that have the intrinsic properties of art. 8. All the things that cause an artistic reaction in the viewer.

Each of these responses provides a very different answer, and hence a very different principle of classification. There is, respectively, a concern with (1) The Public, (2) The Expert, (3) The Self, (4) The Institution of the Museum or Gallery, (5) The Artist, (6) The Discriminations of Common Sense, (7) The Qualities of the Object, (8) Our Aesthetic Response to Objects.

When it comes to Marcel Duchamp’s famous Fountain (1917) (or urinal) we find that there is no definitive answer as to whether or not it is art. For there is no independent fact to which we can appeal to decide the matter once and for all. In a way, then, the point of Duchamp’s piece may be to raise the question about the scope and limits of art rather than to give an answer as to what art is.

UNDERSTANDING AND MISUNDERSTANDING

WHAT DOES THIS GESTURE SIGNIFY?

Gestures are rich in meaning. As a condensed nonverbal source of communication, they appear to be a troublefree way to express approval or disapproval, affection or disaffection, and assent or dissent.

Some gestures, such as pointing, have meanings that appear to be more or less universal. Others, however, such as the thumbs-up sign and its cousin the thumbs-down sign, seem to have different meanings in different contexts. For instance, the thumbs-up sign, when used in the West by pilots before takeoff or by hitchhikers wanting a ride, is interpreted in an affirmative fashion. However, the very same gesture in the Middle East is viewed in the opposite way, and can be insulting. So even a simple gesture such as this can produce grave misunderstandings when interpreted in the wrong way.

The history of the thumbs-down sign is an intriguing one. This sign, which was popular in many Hollywood epics that involved gladiatorial combat, was thought to have been used by the ancient Romans to signal death. However, it seems that Hollywood promoted a misinterpretation of the sign. This misinterpretation arose because Hollywood followed the example set by Jean-Léon Gérôme, a French academic painter, in his 1872 work Pollice Verso. When researching his picture, Gérôme mistranslated the Latin word for “turned in” to “turned down,” so, rather than using the correct Roman sign for death (i.e., the turned-in thumb accompanied by a stabbing motion toward the chest), he employed the thumbs-down sign. It is curious that this misunderstanding has now become so entrenched that the original meaning of the thumbs-down sign has almost been lost.