2

WAYS OF MEANING

Sometimes we mean what we say. Suppose I look intensely at a painting. Then I remark, “The colors are very bright.” What I have said may be literally true. Perhaps I have made this comment because the colors really are very bright. But what I say may not always be what I actually mean. This is because when I say, “The colors are very bright,” I might state this in a sarcastic way. Sarcasm changes the meaning of what I have said. The sarcasm in my voice indicates that what I really mean is that the colors are dull. And in saying that the colors are dull, I may be implying that I don’t approve of, or don’t like, paintings like this. If I am being sarcastic, then I am literally saying one thing while meaning another.

Literal meanings are important when we need to communicate something clearly and unambiguously. Instruction manuals, whether they are verbal or visual, are required to be literal; so are warnings and measurements. These things are literal because this helps people in avoiding potential accidents and preventing possible mistakes.

There are degrees of literalness, however. We can see this when words or phrases are translated from one language to another. Consider the French novelist Marcel Proust’s famous novel, À la Recherche du Temps Perdu. This has received two notable translations in English:

1. In Search of Lost Time

2. Remembrance of Things Past

The first translation is rather more literal and accurate than the second. In this sense, it might be said that the first translation better reflects the nature of the original French. However, the second translation, which is derived from a phrase in Shakespeare’s Sonnet XXX, is less literal, but in some ways more poetic. With these sorts of translations, literal accuracy can sometimes be trumped by other considerations, such as simplicity, clarity, eloquence, elegance, or the requirement to present things in a more contemporary idiom; all of these may alter the original in often subtle, and sometimes profound, ways.

What these translations demonstrate is that meaning can easily shift when we are trying to make a copy or duplication of a work of art, piece of design, musical composition, novel, poem, or section of prose. This is the case whether we are considering a translation, piece of plagiarism, paraphrase, facsimile, adaptation, homage, or tribute. What occurs in all of these cases is that some form of modification occurs to the original, whether we intend it or not. This modification, however slight, may subtly alter the meaning of what is being presented.

As we have seen, to be able to engage in literal communication is very important. Engaging in nonliteral communication, however, is no less important. That is why advertising agencies, poets, humorists, filmmakers, and painters often use it. After all, the truth about the world is frequently more beguiling if we have to do some work to understand it. A nonliteral piece of communication may make us work that bit harder to decipher what is meant.

Just as there are various ways to mean what you literally say, there are also various ways not to mean what you literally say. Strange similes and bizarre metaphors, clever metonyms and genuine ironies, little lies and genuine impossibilities, unusual depictions and curious representations are all of interest to those who study semiotics because they allow us to communicate meanings in a nonliteral way. These nonliteral forms of meaning are often useful because they enable us to make the familiar seem unfamiliar and the unfamiliar seem familiar.

Roland Barthes is a pivotal figure in semiotics who can make the familiar seem unfamiliar. He does this by taking very ordinary-seeming aspects of mass culture and daily life and unmasking their hidden meanings.

One of his best-known examples concerns wrestling. Wrestling is categorized as a sport. This is the meaning that we ordinarily assign to it. Yet Barthes argues that, in spite of appearances, it is not a sport. At first, this claim appears to be so curious, and indeed wrong, that one wonders why he makes it. Yet he makes such a plausible claim for thinking of wrestling in a quite different way that in the end one is persuaded. Instead of being a sport, Barthes maintains that wrestling is really a moral narrative in a spectacular form. For what we really have in wrestling is a cast of characters who represent the twin polarities of good and evil. In this sense, then, wrestling is more like a Greek drama, a pantomime, or a Punch and Judy show. It is there to communicate how ethical battles are fought, and how, in the end, the triumph of good over evil is secured.

In this chapter, we shall examine numerous devices that can be employed to produce meanings of a nonliteral kind. The key concepts will include simile, metaphor, metonym, synecdoche, irony, lies, impossibility, depiction, and representation. All of these concepts are of great consequence because they can help us to produce new insights into the meanings of objects, images, and texts. This, in turn, may allow us to create more resonant meanings in such disciplines as painting, design, advertising, illustration, filmmaking, fashion, and journalism.

SIMILE

WHICH THREE ITEMS ARE MOST ALIKE?

The answer depends on what interests you. We could pick three that are alike in form, three that are alike in size, or three that are alike in color.

When we liken one thing to another we tend to highlight the features that interest us, and we ignore those that don’t interest us. The likening of one thing to another is called a simile. A simile is a stated comparison between two different objects, images, ideas, or likenesses. In everyday life we often use similes without even noticing. They often occur in figures of speech (e.g., busy as a bee, dead as a doornail, flat as a pancake, and crack of dawn). Similes are not confined to verbal communication though. They also occur regularly in visual communication. For example, using an image of a lightbulb above the head of a person to represent the idea that they have just had a thought, or employing an image of a heart to represent love, are well-known visual similes. (They are also clichés.)

Artists and designers are always trying to find new similes. For instance, while a hedgehog is not a brush, it is like a brush in respect of its bristles. Here is how we might think:

First Object | Linking Property | Second Object |

Hedgehog | Bristles | Brush |

This simile is suggestive because if a hedgehog is like a brush then that might suggest that we could design a brush that looks like a hedgehog. The helpful simile, then, is the one that enables us to see an old object or image in a new light by making a connection with another object or image in respect of a certain property or feature.

METAPHOR

HOW IS THIS EQUATION POSSIBLE?

With a metaphor there is an implied comparison between two similar or dissimilar things that share a certain quality. With a simile we say that x is like y, while with a metaphor we say that x is y.

Objects, images, and texts can all be used to create metaphors. Metaphors are often at their most interesting when they link something familiar with something unfamiliar. By drawing attention to the ways in which a familiar thing, x, can be seen in terms of an unfamiliar thing, y, we help to show that the qualities of the first thing are more like the second thing than we had initially thought. Metaphors, then, work by a process of transference. This process of transference shows that while x doesn’t have certain properties literally, it can still have them metaphorically.

When they work, metaphors can also be very persuasive. The schema below shows how the metaphor on the previous page works to persuade us of the qualities of the product.

Signifier | Linking Notion | Signified |

Person (e.g., Carole Bouquet) | = Abstract concepts (e.g., beauty and elegance) | = Object (e.g., perfume) |

The aim of Chanel is to find a metaphorical equivalent for that which they wish to signify (namely, a bottle of perfume). The model Carole Bouquet is a suitable candidate because she has the kind of qualities that the perfume is supposed to embody (i.e., beauty and elegance). Notice, however, that the advertisement could have used a different signifier. Had the designer of the ad thought of highlighting a different set of properties then it might have been structured in the following way, by using a thing rather than a person:

Signifier | Linking Notion | Signified |

Thing in nature (e.g., a waterfall) | = Abstract concepts (e.g., naturalness and freshness) | = Object (e.g., perfume) |

HERE IS ONE ANSWER:

METONYM

WHICH NATIONALITY IS REPRESENTED BY THIS OBJECT?

When one thing is closely associated with—or directly related to—another, it can be substituted for it so as to create meaning. A crown might be used to mean a queen, a shadow in a film might indicate the presence of a murderer, and a sign with an image of an explosion might represent the presence of a dangerous chemical. What is curious about these examples is that the thing actually depicted (a crown, a shadow, or an explosion) is used to stand for something that is not depicted (a queen, a murderer, a chemical). Thus, while the thing that is being referred to is missing, its presence is still implied.

When one thing is substituted for another in a piece of communication we call it a metonym. Metonyms use indexical relationships to create meanings. Below are some examples of metonyms.

The intriguing thing about all of these metonyms is that they depend on extensive cultural knowledge. So in order to know which nationality is being represented by the fez on the last page you have to know that they are worn in Turkey. (Though note that a fez may also stand for a particular type of user—a Turkish man of a certain age.)

Things | Meaning | |

Statue of Liberty (object) | indicates | Freedom (concept) |

A brush (object) | indicates | Painting (activity) |

A throne (object) | indicates | A monarch (person) |

Images | Meaning | |

A cartoon of a flattened thumb (effect) | indicates | The presence of a hammer (cause) |

A picture of the White House (place) | indicates | The president of the USA (person) |

A photograph of a jacket (object) | indicates | A store where clothes are sold (place) |

Words | Meaning | |

Watergate (place) | indicates | The impeaching of President Nixon (event) |

Charleston (place) | indicates | Dancing (activity) |

Einstein (person) | indicates | Genius (concept) |

SYNECDOCHE

CAN YOU RECOGNIZE THIS PERSON BY THEIR HAIRCUT?

Sometimes in semiotics what matters is not what you put into a piece of communication, but what you leave out. In order to represent Elvis you may only need to use part of him. In this case his haircut will suffice. Using a part of something to stand for the whole thing, or the whole thing to stand for a part, is called synecdoche. Another example might be this: using an Italian to represent the people of Italy (here the part stands for the whole) or using a map of Italy to represent an Italian person (here the whole stands for a part).

The part/whole relationship is one example of synecdoche. Other examples include that between member and class, species and genus, and an individual and a group. Here is an example of the last kind. Newspapers and television programs often use individual people to stand for a category of persons that they want to portray as a group. So they will report on a story about a particular criminal who is intended to stand for criminals as a group. This works as an act of persuasion because it is easy to get human beings to move from thoughts about a specific case to thoughts of a more general kind that are also negative. In this instance, the activities of a specific criminal will serve to remind us of why we dislike criminals as a group.

Suppose you were given the task of raising money for a charity for the poor. Would it be better to provide abstract statistics concerning the malnourishment of your target group or would you be better off presenting a story about a particular person in that group who was malnourished (and in that way use them to represent the group that you are trying to help)? Those advertisers who are fond of using synecdoche in their work would probably opt for the latter, because the personal case will tend to awaken more sympathy than a set of rather impersonal statistics.

IRONY

WHAT IS IRONIC ABOUT THIS VASE?

This work is called A Vase By Any Other Name. It was designed by Sean Hall.

A vase for a rose is supposed to sustain the flower, while also protecting people from its thorns. The irony of this work is that it does afford protection from the stem of the rose, but at the same time creates what looks like an equal problem by situating a number of glass thorns on its outside surface. Irony is used in this context to highlight features that will serve to create an effect that is at once amusing and lightweight.

Irony is about opposites. When someone makes an ironic statement they will use the word “love” when they mean “hate,” or the word “true” when they mean “false,” or “happy” when they mean “sad.” In speaking like this they are expressing a belief or feeling that is at odds with what they are saying on the surface. Irony of this kind can occur in everyday speech, but it can also occur in works of literature, music, design, and art.

The problem with using irony is that people don’t always notice it. This is because if something looks serious on the surface then it is all too easy to take it seriously. In order to communicate the fact that you are being ironic, then, you may need to engage in gross understatement or gross overstatement. However, by exaggerating things in this way to make yourself clearer to others your ironic comment may lose some of its power. So to be ironic in the first place might require a culture in which irony is regularly used and understood.

LIES

IS THIS SENTENCE LYING?

It is sometimes hard to tell where the truth ends and lies begin. That may be true of this sentence. Or it may not be.

So what is a lie? A lie is a claim that is literally false. It is, therefore, unlike a factual description, which is true. It is also unlike a prescription, which, given its status as an opinion, is neither true nor false. It is like an ironic comment, at least in terms of its modality (see below), as it is literally false. However, it is quite unlike an ironic comment in that it is not intended to amuse, so much as to mislead.

To see the difference between facts, values, irony, and lies consider someone who says, “That’s a good haircut.”

Lies are built into the fabric of everyday life. Lies are like truths in being almost never pure and rarely simple. The catalog of human lies—which depend for their existence on liars of various kinds—has been compiled over centuries by (among others) storytellers, biographers, painters, advertisers, politicians, salesmen, lawyers, children, and the list could continue. In fact, a liar is anyone who has an interest in cheating, deceit, selfishness, exaggeration, pretense, and distortion.

But does that make lying bad? Not necessarily. For perhaps semiotics is about creating the lies that make us see the truth.

* N.B. This could be a lie about factual information (because the haircut has not been done skillfully) or a lie about my preferences (because I do not like the haircut).

IMPOSSIBILITY

IF YOU ADD A SQUARE TO A CIRCLE DO YOU GET A SQUARE CIRCLE?

If something is not literally possible we say that it is impossible. But things can be impossible in different ways. A square circle is not logically possible—though that may not stop us trying to imagine one. The fact that there are no people from the future here now might suggest to us that backward time travel is not scientifically possible—yet filmmakers often try to represent it. It is physically impossible for human beings to fly unaided (unless, perhaps, they attempt it in zero gravity), but that does not prevent speculation —and dreaming—about what it might be like to have the experience.

What is literally possible sets a limit for us. Possibilities (and impossibilities) that go beyond what is literal are rather less limited. In fact, it might be said that contemplating impossibilities is actually liberating, both intellectually and imaginatively. It may be impossible to ignore a notice that says, “Please Ignore This Notice.” It may be impossible to know everything. It may be impossible to understand infinity. It may be impossible to step into the same river twice. It may be impossible to think of nothing. It may be impossible to slow life down—or even stop it. It may be impossible to experience death itself (rather than the process of dying). Yet all of these “impossibilities” open up our thinking in different ways.

That which is not possible has meaning for humans in a way that it cannot for other animals. Other animals are limited because they are actually too literal.

DEPICTION

WHAT IS DEPICTED ABOVE THE HEAD OF THE CENTRAL FIGURE?

The answer seems easy. It is a bird. And the bird looks like a dove. However, knowing what is being depicted in a picture is not as simple as it looks. This is because in order to know what is being depicted we may need to know how it is being depicted.

In this case, the dove is depicted in perspective. Perspective is a convention that has to be read correctly if it is to be understood. It is not something that is simply transparent to the viewer of an image—even if it sometimes seems so. Nor is it a mere recording of what appears on our retinal image. Instead, perspective is a code that has to be properly interpreted if it is to be deciphered. And for the code to be deciphered the viewer needs to realize how objects can present different facets of themselves from different angles, and how shadows and shading change when an object is viewed from these different positions. (For example, looking straight at an object is very different from looking up at it or down at it.)

What is depicted in a picture may also be different from what it represents. In this picture by Piero della Francesca we see a dove. The dove is the object depicted. But the dove represents the Holy Ghost. So when we want to know what is depicted in a picture we need to ask: “What is the picture of?” And when we want to know what is being represented we need to ask: “What does the thing depicted in the picture mean?” While a picture of a dove may mean that there is a dove, it may also mean something else entirely.

REPRESENTATION

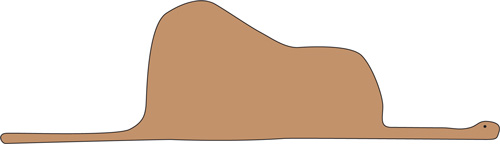

WHAT DOES THIS DRAWING REPRESENT?

It looks a bit like a drawing of a hat. Does the drawing only represent a hat, though, or does the hat in turn represent something else? And how can we tell?

Actually, this is a picture of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant. The elephant is inside the boa constrictor so you can’t see him. The image is taken from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s children’s book The Little Prince. The narrator of the book explains the picture with seeming exasperation, because, as he points out, grown-ups always have to have everything explained, whereas children, who often have better insight into such things, do not. (This point, of course, is intended to appeal to the children, who are supposed to be the main readers of the book.)

And that sentiment is right when it comes to representation. Adults often have to have things explained to them. As adults we find that interpreting a drawing made by a small child can be quite difficult, because while the meaning of the drawing is often transparent to the child it is frequently opaque to the adult. The problem is often that the adult needs more information to be provided in order to understand what the child is trying to say. Indeed, when we ask a young child what they have drawn in a picture we often find that something that we did not expect has been presented to us.

What is fascinating about children is that while they are often literal in their approach to perception, they are naive as regards the conventions of representation. This means that they may devise highly creative forms of representation that as adults we would never consider. It may have been this point that Picasso had in mind when he pointed out that it took him his whole life to gain the insight needed to draw like a child.