1

SIGNS AND SIGNING

There are many views about how we make sense of the world. In one, there is an independently existing world and it is up to us to devise signs and systems of communication to coincide with it. The idea being that it is possible to “remake” aspects of the world by using an imitation or representation of it—what might, broadly speaking, be called a “language.”

The table below presents a rather naive and simplistic view of how this might work. One problem with it is that systems of communication themselves have an influence over—and can alter or augment—the way in which the world itself is viewed. In the field of semiotics, it is argued that the communication systems we devise actually frame, or dictate in some way, how we see the world. In other words, the world is not directly accessed through these various systems of communication; it is mediated through them. The systems themselves are apt to change what we think the world is really like, sometimes quite radically.

This, roughly speaking, was the view of the first semiotician, Ferdinand de Saussure. For him, communication systems —particularly, natural languages—were not there simply to name and classify things as part of “reality.” Instead, they also had a social aspect, reflected in the way in which they were structured. For Saussure, signs had two elements to their structure: the signifier and the signified. Basically two sides of the same coin, the signifier was that part of the communication that carried the message (e.g., a certain pattern produced by a sound, such as the word “house”); the thing signified was that which was communicated by that sound (e.g., the concept house). As is obvious, the sound and the concept go together because in order to indicate (say) the presence of a house by using language you have to say (or write) the word “house.”

| Human Systems of Communication | Forms of Correspondence | The World |

| Languages | Picture | Reality |

| Propositions/Statements/Sentences | Match | Thoughts |

| Words | Exemplify | Facts/Values |

| Speech | Mirrors | Opinions and Feelings |

| Gestures | Echo | Beliefs and Emotions |

| Concepts | Label | Concrete/Abstract Ideas |

| Symbols | Embody | Meanings |

| Images | Represent | Things |

| Maps | Describe | Spatial Relationships |

| Diagrams | Chart | Viewpoints |

| Mathematical Formulae/Equations | Model | Relationships |

| Statistics | Measure | Quantities |

Saussure’s distinction between signifier and signified is demonstrated in this chapter, as is the work of another seminal figure, Charles Sanders Pierce. For Pierce signs had three elements: the representamen, the interpretant, and the object. We might say these were:

1. a sign vehicle (which is the medium of communication)

2. a sense or meaning

3. a reference

For example, I might point to a photograph of a planet or say the words “the morning star.” By using the photograph or the phrase (the medium of communication), I make it clear I am talking about a certain planet that appears in the east before sunrise (this is the sense or meaning) and that the planet itself is Venus (this is the reference).

Pierce also made a distinction between the three basic forms signs might take: the icon, the index, and the symbol. These will be explained in the chapter entries, though they will be given a rather Saussurean gloss.

As well as drawing upon Saussure and Pierce, this chapter will explore the sorts of journeys different messages take as they travel from senders to receivers and (perhaps) back again. Analysis of these journeys can help us understand what can and does happen to make communication a success or a failure. Below are examples of some of the key stages:

Trajectory of Communication |

Key Semiotic Concept | |

1. Object-based Communication |

A designer Wishes to design a vacuum cleaner He designs a very efficient vacuum cleaner The design is manufactured in plastic and metal It is sold in a store without the instructions A buyer purchases it The buyer tries to use the product, but unsuccessfully The buyer sends for the instructions, which enable him to use it |

Sender (who) Intention (with what aim) Message (says what) Transmission (by which means) Noise (with what interference) Receiver (to whom) Destination (with what effect) Feedback (and with what reaction) |

2. Image-based Communication |

A painter Wants to paint a portrait He paints a portrait that resembles the sitter It is painted on paper with watercolors It is hung in a gallery under artificial light, which changes its color A viewer sees it He hangs it over the fireplace where it looks dull The picture has too little light, so the viewer rehangs it near a window |

Sender (who) Intention (with what aim) Message (says what) Transmission (by which means) Noise (with what interference) Receiver (to whom) Destination (with what effect) Feedback (and with what reaction) |

3. Text-based Communication |

A writer Aims to produce a text on semiotics He writes a book explaining the complexities of the subject It is printed A printing error occurs A reader reads it The reader, not detecting the printing error, is confused The error is corrected and the reader is no longer confused |

Sender (who) Intention (with what aim) Message (says what) Transmission (by which means) Noise (with what interference) Receiver (to whom) Destination (with what effect) Feedback (and with what reaction) |

SIGNIFIER AND SIGNIFIED

WHAT DOES THE APPLE IN THIS PICTURE SIGNIFY?

This painting by Lucas Cranach (1472–1553) depicts Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. The apple represents the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. Satan, who takes the form of a serpent, uses the apple to tempt Eve. Eve picks the apple and gives it to Adam. With this act Adam and Eve fall from grace in the eyes of God.

It is easy to assume that the image of Eve being tempted by the apple accurately reflects the story in the Bible. But in the Bible there is no mention of an apple. Fruit is mentioned, but not apples. So perhaps it was really an orange that tempted Eve. Or a fig.

What seems to matter in the picture by Cranach is that the apple (what we call the “signifier”) is the fruit used to signify temptation (what we call the “signified”). However, while the apple means temptation, some other fruit could have been chosen to represent the same idea. It is only because there is already a well-established connection in our minds between the appearance of an apple and the idea of temptation that this fruit is used in the picture. It is this connection that makes the picture successful in terms of communication.

There are numerous relationships that can exist between signifier and signified. Two important things about the relationship stand out though. One is that we can have the same signifier with different signifieds. The other is that we can have different signifiers with the same signifieds.

In the first three examples below, the same signifier gives rise to different signifieds:

Signifier | Signified | |

Apple | means | Temptation |

Apple | means | Healthy |

Apple | means | Fruit |

However, in the next three examples, different signifiers (depending on whether the language spoken is English, French, or German) give rise to the same signified:

Signifier | Signified | |

Apple | means | Apple |

Pomme | means | Apple |

Apfel | means | Apple |

SIGN

CAN YOU MAKE SENSE OF THESE DOTS?

These symbols are written in Braille. In order to decode them you have to know that each set of dots represents a letter, which, in turn, makes up a word. In this case the word is “blind.” The word “blind” is the carrier of the meaning. This is the signifier. The meaning of the word, on the other hand, is that which it signifies (e.g., that someone lacks sight).

Signs are often thought to be composed of two inseparable elements: the signifier and the signified. One thing that is intriguing about the relationship between the signifier and the signified is that it can be arbitrary. For example, when I use the word “dog” in order to talk about a certain furry four-legged domestic creature, I employ a signifier that is arbitrary. The sound made by the word “dog,” when uttered, is intrinsically no better than the made-up sounds “sog,” “pog,” or “tog” for talking about this animal. All these words could have been used to communicate the meaning of “four-legged domestic creature that can make the sound woof.” We just happen to use the word “dog,” while in Germany they have chosen hund and in France, chien.

Many of the signs we use to communicate are arbitrary in the sense that they are not immediately transparent to us. For this reason they have to be learned with the conventions of the language in which they are embedded before they can be used. Once these conventions have been learned, however, the meanings that are conveyed by using them are apt to seem wholly natural. Yet by thinking of meanings as natural we do ourselves a disservice. This is because what is often seen as natural is just the product of various cultural habits and prejudices that have become so engrained that we no longer notice them.

ICON

WHAT ARE THESE OBJECTS?

These are Inuit maps. They are made from wood. Rather than being visual, they are tactile. The Inuit hold this kind of map under their mittens and feel the contours with their fingers to discern patterns in the coastline. The advantage of these maps is that they can be used in the dark, they are weatherproof, they will float if you drop them into the water, and they work at any temperature. They will also last longer than printed maps.

Although these Inuit maps are highly abstracted, they still resemble the shape of a coastline. While some maps follow the geography of the place that they represent in a fairly exact way, others do not. When specific information about the environment is represented on a map in an abstract way we tend to say that the map is schematic, whereas when a map resembles the world in a more concrete and exact way we say that it is topographical.

With any icon there is some degree of resemblance between signifier and signified. The degree of resemblance can either be high or it can be low (as we have just seen in the case of maps). There are many other examples. For instance, a portrait may look very like the real person or it may look a little like them— enough, say, for them to be recognizable.

Here are some examples of an iconic relationship between signifier and signified:

Signifier | Signified | |

Line drawing | resembles | The place depicted |

Sculpted portrait in clay | resembles | The person portrayed |

Colored photograph | resembles | The object photographed |

Sound effect (of footsteps) | resembles | Footsteps |

An organic compound | resembles | The smell of roses |

A chemical mix | resembles | The taste of cheese and onion |

INDEX

WHAT HAS HAPPENED TO THE WOMAN IN THIS PHOTOGRAPH?

The woman in this photograph by Cindy Sherman looks as if she is dead.

Representational photographs present us with a problem because they often appear to have been caused by real events even when they have been faked. This photograph highlights the very real and disturbing difference between how we might feel about an image of an actual death as opposed to its mere simulation. The photograph also raises the question of how we would be able to tell the difference between the two in certain cases.

When there is a physical or causal relationship between the signifier (i.e., the photograph) and the signified (i.e., what the photograph depicts), the nonarbitrary relationship that exists is said to be indexical.

Other examples of an indexical relationship are shown below.

If only for survival purposes, it is important that we can detect the causal link between a signifier and what is being signified. For instance, we need to know that smoke means (and is often caused by) fire or that a thermometer changing means (and is usually caused by) a rise or fall in temperature. We can see that a failure to detect these things is important when we realize that such a failure can result in mortal danger.

Signifier | Signified | |

A black eye | is caused by | A punch |

A thermometer changing | is caused by | A rise, or fall, in temperature |

Smoke | is caused by | Fire |

A rash | is caused by | An infection |

A knock | is caused by | Someone at the door |

A weathercock moving | is caused by | The wind |

Ticking | is caused by | A clock |

A photograph | is caused by | A real place |

A recorded voice | is caused by | A person speaking |

A defensive posture | is caused by | An emotional attitude (e.g., fear) |

Handwriting | is caused by | A person writing |

SYMBOL

WHAT DOES THIS SYMBOL MEAN?

The symbol on the last page looks like the Nazi swastika. In fact it is an Indian swastika. In Hinduism and Buddhism the swastika stands for good luck. With the Indian swastika the “L” shape is inverted, unlike its Nazi counterpart.

It is often remarked that the Nazi swastika is a powerful and disturbing symbol. The word “symbol” in Greek means “to throw together.” In semiotics one thing can be “thrown together” with another in such a way that a relationship is created whereby the first symbolizes the second. Here are some obvious visual examples:

Symbol | Meaning |

Scales | Justice |

Dove | Peace |

Rose | Beauty |

Lion | Strength |

With these symbols the meaning that is created is related to the nature of the object: balance is important for justice; doves are peaceful creatures; roses are beautiful; and lions are strong. However, there are some symbols where the relationship between the symbol and its meaning is less obvious:

Symbol | Meaning |

Sword | Truth |

Lily | Purity |

Goat | Lust |

Orb and Scepter | Monarchy and Rule |

With these examples we need to know what the symbols stand for in advance if we are to understand them. We can’t work it out just by looking at them. In semiotics the word “symbol” is used in a special sense to mean literally any sign where there is an arbitrary relationship between signifier and signified. In other words, it is wider than the more traditional sense of the word “symbol,” as used above. The following, then, are also symbols in semiotics:

Signifier | Signified | |

Shaking hands | Arbitrary relationship | A greeting |

Black tie | Arbitrary relationship | A formal occasion |

Bleep, bleep | Arbitrary relationship | The telephone needs answering |

A black flag | Arbitrary relationship | Danger |

Cheese | Arbitrary relationship | The end of a meal |

The word “cat” | Arbitrary relationship | A cat |

SENDER

WHO IS SENDING THIS MESSAGE?

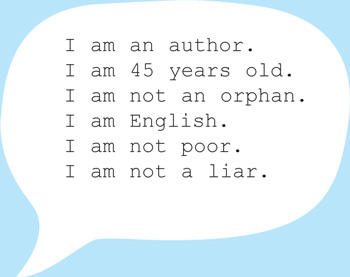

The first five sentences in this speech bubble provide information that helps us to form a picture of the individual who we think is sending the message. The information tells us who the person is, how old they are, where they come from, and what their life is like.

However, the last sentence seems anomalous, and may lead us to ask certain questions. Is this a message from a child who lies about certain things? Is the whole message a lie? Is this a genuine message? Or is it just a fictional piece of dialogue?

A six-year-old black child did not write the sentences in this speech bubble. The author of this book wrote them. But has the “real” sender of the message, namely the author, chosen them for a special reason? Is he just using them to make a point about the difference between the real author (himself) and an authorial persona (the person he might pretend to be)? Or is there some other meaning that lies behind these words?

Consider the following speech bubble:

These sentences provide us with vital information about another putative person. But, once again, we can ask: “Is this person real or is he fictional?”

It is always important to remember that where a message says it is from may be very different from where it is really from. The former is what we call the “addresser.” This consists of a message that is constructed, and it may be real or imaginary. On the other hand, the latter is what we call the “sender.” This consists of a message from a real person. Of course, whether we can always tell the difference between these two things may be another question.

INTENTION

WHAT DO YOU THINK OF THIS PICTURE?

Even if we ought to judge a picture, object, or piece of text in isolation from the intentions of its maker, this is hard to achieve in practice. Consider the painting on the previous page. There are several possibilities as to its creator. An adult, a child, or a machine might have made it. Surely if we can discover who made it, that will influence the way that we judge it, whether or not it ought really to influence us.

In fact, a chimpanzee called Congo made this picture. Once you know that, it is hard to see it in the same way. Over the course of his life Congo completed around 400 drawings and paintings. He was the subject of a study into the drawing and painting abilities of apes by the behavioral psychologist Desmond Morris. Morris argued that the fundamentals of creativity could actually be discerned in the paintings of apes. He claimed that a sense of composition, calligraphic development, and aesthetic sensibilities are apparent (even if only at a minimal level) in the picture-making of apes.

Now imagine that I lied. Suppose a well-known artist created this picture. You might also suppose that the work of this (human) artist sells for vast sums of money. Once we know that a human being rather than an ape produced this image do we start to see it differently? Do we read human intentions and feelings into the picture where there were none before? Do we also begin to see aesthetic qualities in the image that were not present before? And do we also see monetary value in the picture that was not there before?

Whatever you think of this work, and however you would wish to judge the person or thing that made it, it is hard not to be influenced in our judgments by what we take to be the intention behind it.

MESSAGE

WHAT IS THIS MESSAGE REALLY SAYING?

The meaning of the message seems obvious. It appears to be saying that shopping gives us a sense of who and what we are as human beings.

Perhaps there is a deeper message though. To see this we need to understand that “I shop, therefore I am” is derived from “I think, therefore I am,” which was used by the seventeenth-century French philosopher René Descartes.

Descartes was the first modern philosopher. He believed that to build a system of knowledge one must start from first principles. To find secure foundations for his philosophy he employed what he called “the method of doubt,” which consisted of trying to doubt everything that it was possible to doubt. This led Descartes to the conclusion that there was only one thing of which he could be certain, the famous cogito ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”). The idea behind the cogito was this:

If I think, it follows that I think.

If I doubt that I think, it also follows that I think. Therefore, either way, it follows that I think.

“I think, therefore, I am” and “I doubt, therefore, I am” were equally true for Descartes, as even doubting is a kind of thinking. This enabled Descartes to conclude that what I am, fundamentally, is a “thinking thing.”

The deeper message behind “I shop, therefore I am,” then, may be this: it is surely ironic that where once we would try to secure our belief systems on foundations gained by the profound activity of philosophizing, we now rely on the trivial and banal-seeming activity of shopping to tell us who and what we are.

We can scarcely imagine a world without the messages of advertising. But take a moment to think about how we would view the world if all advertising suddenly disappeared.

TRANSMISSION

HOW IS THE MESSAGE OF THE MONA LISA TRANSMITTED?

Messages are always transmitted through a medium. The medium carries the message from the sender to the receiver. The medium may be:

Presentational: through the voice, the face (or parts of the face such as the mouth or the eyes), or the body (or parts of the body such as the hands).

Representational: through paintings, books, photographs, drawings, writings, and buildings.

Mechanical: through telephones, the internet, television, radio, and the cinema.

The message of the Mona Lisa is transmitted through all three mediums. It uses the presentational medium of facial expression, the representational medium of painting (in its original form), and the mechanical medium of the internet and television (in its digital form).

The enigmatic expression of the Mona Lisa is often remarked upon. To see how this expression is transmitted, consider the following drawings:

In both of these drawings the eyes are identical in terms of shape, tone, and position. What makes the eyes in the first picture seem happy, and the eyes in the second picture seem sad, is the mouth. The mouth is the transmitter of emotion; the eyes themselves are expressionless.

So even though we know that the charm of the Mona Lisa lies in her gentle smile, the lesson from these highly abstracted images of a face may be that very little is transmitted to us by the eyes. The eyes, it seems, are not the windows of the soul after all. The window of the soul is the mouth.

NOISE

HOW SHOULD WE COMMUNICATE DANGER TO FUTURE GENERATIONS?

Imagine that you had to tell someone living in 2000 years’ time about a danger that exists now. Commercial nuclear reprocessing has ensured that thousands of gallons of dangerous radioactive liquid will still be active in thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of years to come. And if we don’t tell future generations where and how we have stored this waste they may be exposed to it without suspecting that it is highly toxic.

Communicating danger to people in the future seems to be simple. But it isn’t. This is because over such a long period a message can easily be distorted or altered without this being in any way intended. (This distortion or alteration in the meaning or method of transmission of a message, whether intended or not, is called “noise.”) Languages, both written and spoken, always change. The meanings of symbols are often lost in the passage of time. In fact, most messages are bound so closely to a particular period and place that even a short time later they cannot be understood. Therefore, ensuring that a message created now can be decoded by future generations is highly problematic.

How to pass on messages about this nuclear peril is not obvious. Perhaps we can use words, pictures, mathematical symbols, smells, and sounds to help us. Perhaps we can create a culture that will spread the myths necessary to deter any curiosity about the nature of these storage systems if they are chanced upon. The prospects, however, seem bleak. Even when you think that you have a message that is clear and precise in the present, it can still be misinterpreted. And that, as we know, can lead to disaster.

RECEIVER

HOW WELL DO YOU UNDERSTAND HIM?

Did you interpret it as one of the following?

I didn’t eat Grandmother’s chocolate cake.

(Paul ate Grandmother’s chocolate cake.)

I didn’t eat Grandmother’s chocolate cake.

(I sat on Grandmother’s chocolate cake.)

I didn’t eat Grandmother’s chocolate cake.

(I ate Susan’s chocolate cake.)

I didn’t eat Grandmother’s chocolate cake.

(I ate Grandmother’s fruitcake.)

I didn’t eat Grandmother’s chocolate cake.

(I ate Grandmother’s chocolate biscuit.)

How we make sense of this message depends on how we interpret it and who we think is receiving it. The message says that it is being sent to a certain granddaughter. However, the granddaughter is actually imaginary. The person who is receiving the message is really a reader of a book on semiotics (namely you!). That is why in semiotics there is a distinction between the “receiver” (the actual person who gets the message) and the “addressee” (the person, whether real or imaginary, who is said to be the target of the message).

Below are some examples of familiar fields of communication with different senders and receivers.

In all these cases a message travels between a sender and a receiver in a specific context and through a specific object. The aim of the sender is to make sure the message has reached the right receiver without anything going wrong.

DESTINATION

HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT THIS PICTURE?

This photograph was taken on Sunday, November 24, 1963. It shows the murder of Lee Harvey Oswald by Jack Ruby. Lee Harvey Oswald is said to have murdered President John F. Kennedy on the afternoon of November 22, 1963. However, many conspiracy theories remain surrounding the assassination.

The murder of Lee Harvey Oswald and the assassination of President Kennedy are well-known historical events. But how we feel about these events changes according to what historians (and conspiracy theorists) tell us. For example, you may think that the murder of Oswald is deplorable until you discover that he killed Kennedy. You may think that Oswald was not the person who really killed Kennedy and hence that his murder by Ruby was unjustified. Or else, the shooting may seem shocking when you discover that Ruby may have been a mobster, an intelligence agent, and small-time hustler who allowed himself to shoot Oswald simply out of a sense of moral indignation.

When the message in this photograph has been successfully decoded and interpreted we can say that it has reached its destination. The destination is the end point in the journey of the message. One problem in semiotics is that the message that arrives at the destination is not always the same as the one that has been sent. The problem occurs because the message can be altered during its journey. This can happen due to the quality of the message, because of an ambiguity in its expression, or it can come down to failure in its transmission, whether intended or not. In this instance, our ability to decode and interpret the message depends very much on what we know about, and how we judge, the historical events that surrounded the murder of Lee Harvey Oswald.

FEEDBACK

HOW DO YOU OPEN THIS DOOR?

Even highly intelligent people sometimes pull a door handle when there is a large sign on it saying “push.” If misusing objects like this has nothing to do with intelligence, how does it happen? The problem occurs because of miscommunication. The door handle looks as if it should be pulled, so people tend to pull it. In this instance, it is as though the message that the handle is communicating has managed to overpower the presence of the sign. Here, the word “push” is supposed to act as a feedback mechanism. It is a message for those users who have not yet received the message to push. But it will often fail because a handle gives us a certain visual and tactile cue that indicates a pulling action. We can solve this problem by putting a flat metal panel on a door (instead of a handle) in the same position. Now there is no way of undertaking a pulling action, so we know that the door must be pushed.

Feedback mechanisms exist so that receivers can be corrected when a message appears to have reached its final destination in the wrong form. The right feedback allows us to adjust our response to the message that is being communicated. Feedback is often useful, then, because it can alter the action that we take as a result of what we think the message really is.

Here is an example of an accident that can occur when an object gives the wrong kind of message to its user. A woman wants to reach a high shelf. She requires a low, flat, solid surface to step on. She reaches for a child’s plastic table that appears to have these qualities. The table breaks and the woman falls off, sustaining a serious injury. The table has what is called an affordance. (The word “affordance” refers to those properties, both actual and potential, that determine the possibilities for how an object looks as if it should be used, whether or not the person who designed it intended it to be used in that way.) In this instance, the table looks as if it can be stepped upon. That is what the woman does, and hence the accident occurs.

The message that the child’s table was sending could have been corrected by using a feedback mechanism. For example, the feedback might have consisted of a label stuck to the top of the table that read: “This table will not hold the weight of a person.” A simple sticker like this may have prevented both the accident and any litigation that might have followed it.

It should be noted that feedback can take numerous forms: a seat belt clicks to show that it has been correctly used; a website provides a reminder of the parts of a form that we have forgotten to fill in; a whistle tells us that the kettle has boiled.