5

TEXTUAL STRUCTURES

As a universal medium of communication, human language makes us different from other animals. Just how different can be gleaned from the fact that the average reading vocabulary of a human is around 40,000 words, whereas even the most intelligent ape that has been taught a language-like system of communication can muster only about 400 signs in total.

Natural language, which enables human beings to have highly sophisticated thoughts, has an orderly structure. In the traditional view, one part of the structure is called “syntax,” another is called “semantics,” and a third is called “pragmatics.” The syntax of language tells us when a sentence has been constructed in a fashion that is grammatically correct and when it has been constructed in a way that isn’t. Semantics is about what the sentences we construct, by using various grammatical rules, mean. Pragmatics concerns the way that meanings are affected by context, both individual and social. Although the grammatical rules for constructing sentences, the meanings that they communicate, and the social and cultural contexts in which they appear are conceptually distinct, in practice they operate together in numerous ways, only some of which are linguistic.

One key interest that semioticians have is how human language is used to create meaning. The basic unit of natural language is, of course, the word. For the most part, however, we interpret words not so much individually but as parts of sentences. By expressing ourselves in sentences we are able to communicate our thoughts to others. In other words, sentences express thoughts. Yet sentences, in turn, can change their meanings according to context. Consider the following:

1. “I am the Queen of Hearts.”

2. “I am the Queen of Hearts.” These were the exact words that the mouse uttered.

3. “I am the Queen of Hearts.” These were the exact words that the mouse uttered. Lewis Carroll was dreaming that a mouse was talking to him.

In the first instance, we might think that a person is speaking. Yet the second sentence tells us that it is not a person, but a mouse. This changes how we interpret the first sentence. However, it is only when we get to the third sentence that we discover that the first words are spoken by a mouse that is appearing in a dream. This final sentence forces us to rethink the meanings of the other two.

The meaning of these three sentences may also change according to how the wider context is constructed. For example, given the reference to Lewis Carroll, we may think that these three sentences are taken from Alice in Wonderland . This gives the sentences one meaning. However, if Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland is not being referred to here, the meaning will change accordingly.

Meanings can be generated by the different aspects of text:

• The form of the text. This consists of such things as the shapes of the letters (e.g., thin, thick, large, small, shadowed, non-shadowed); the kind of font that is used (e.g., Helvetica, Bodoni); whether that font is rendered plainly, in italics, or in bold; the color of the letters (e.g., saturation and modulation); and the stye of layout (e.g., where the words are placed on a page, how they are aligned, whether they are bunched together or spaced out, whether—or how—they overlap, and where the page breaks occur). All of these formal features may give weight and stress to some words rather than others and thereby affect what is being communicated.

• The content of the text. This consists of the meaning of the words along with their reference—if they have one. The content is also produced by such things as punctuation, which can alter what is being said or communicated, and the context in which the words and sentences appear (as we just saw with our Lewis Carroll example).

Meanings, then, can be analyzed through aspects of text alone. However, text can also be judged in relation to how it interacts with various images and objects. (These mixed forms of communication may need to be treated as integrated wholes for the purpose of analysis.) Once again, it is instructive to make a distinction between form and content. Thus, the following elements of images and objects need to be considered:

• The form of the image. This consists of the various basic structures (composition and framing), pictorial devices (perspective and forms of distortion), and formal elements (color, line, and tone) that organize the image.

• The content of the image. This might consist of something concrete that we identify the image as being of: a cat, a car, a chair, a house, a person, a country. Or else it might be related to something more abstract, such as the hearts drawn coming from a comic-book character that signify love or desire.

• The form of the object. This consists of the various structures (composition and orientation); shape orientations (the front and back, top and bottom, along with the right side, left side, and underside of the object); the formal elements (color, texture, and material); and the kind of mimicry that the object might take on (e.g., a sofa in the shape of lips). These things are part of the physical makeup of the object and affect our experiences of it accordingly.

• The content of the object. This consists of what the object is: a sculpture, a product, a building, or a piece of clothing; and also what an object might be taken to represent: a sculpture might represent wealth, a product might represent efficiency, a building might represent power, and a piece of clothing (such as a uniform) might represent authority.

This chapter, then, will focus on the ways in which language can be used in very different ways to communicate with others. In particular, we will be concerned with the roles of the following: readers and texts, words and images, functions, forms, placing, prominence, voices, intertexuality and intratextuality, and paratext and paralanguage.

READERS AND TEXTS

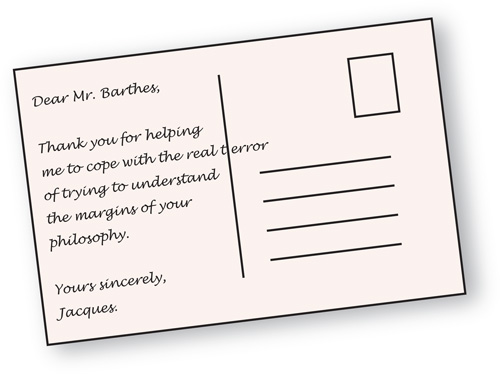

WHAT IS CURIOUS ABOUT THIS POSTCARD?

There are many ways to write a text. There are also many ways to read one. When readers read a text they often make very different assumptions about it. Some of the standard assumptions that are made in reading texts are listed below under the heading of “structuralism.” This structuralist list reminds us that we often analyze the meanings of a text in terms that will give it a unity and overall sense. Now compare these assumptions with those of the post-structuralist (which are also listed below). In contrast, the post-structuralist embraces the idea that a text may not be coherent and may not make any sense overall.

Structuralism | Post-structuralism |

Consistency | Inconsistency |

Balance | Imbalance |

Harmony | Disharmony |

Unity | Disunity |

Coherence | Incoherence |

Completeness | Incompleteness |

Resolution | Conflict |

Presence | Absence |

Belief | Paradox |

Actions | Omissions |

Stability | Instability |

Reliability | Unreliability |

Non-contradiction | Contradiction |

Linearity | Non-linearity |

Fixed viewpoint | Flexible viewpoint |

Foreground | Background |

Sense | Nonsense |

Perfection | Imperfection |

Regularity | Irregularity |

Notice that both structuralist and post-structuralist concepts can be used for the interpretation of images and objects just as much as for texts. For instance, instead of attending to the foreground of an image to find its meanings (which might happen if we are structuralists), we may look more at its background to find its meanings (which might happen if we are post-structuralists). Rather than examine the qualities of an object that make it reliable (which we might do if we are structuralists), we may shift this emphasis and try to examine the qualities that make it unreliable (which we might do if we are post-structuralists).

In the light of the structuralist and post-structuralist concepts listed above, there are at least two ways to read and understand the postcard on the previous page. We could see it as a genuine postcard. This would mean trying to make complete sense of it. Or else, we might see it as a playful form of nonsense, where there is no stable meaning to which the reader might gain access. In fact, the postcard, which purports to be from Jacques (Derrida) to Roland (Barthes) is intended to be playful in the way it refers to the work of those two authors.

WORDS AND IMAGES

WHICH TEXT IS TELLING THE TRUTH?

To understand some of the numerous interactions that can occur between words and images one might first consider books that have no text. In books for small children that have pictures but no writing parents are forced to make up large parts of the story. This gives a great deal of control to the reader. In this instance, the reader becomes a key locus for the reading of the book. Now, in contrast, consider a text without pictures or illustrations of any kind, such as a novel. In this case, as there is no visual guidance, we have to rely on textual descriptions in order to know what the characters or places in the novel look like.

Images on their own are often so open to interpretation that they fail to provide a stable meaning for the reader to grasp. This may be why we might need to supplement them with words. Words help to reduce the number of interpretations available. Words aid us in anchoring images. (Just how important it is to anchor an image properly can be seen from the picture on the previous page. For it obviously matters greatly whether a glass turns out to contain poison rather than holy water.)

The problem of open interpretation occurs with texts too. And this is where illustration comes in. For example, Sir John Tenniel’s illustrations for Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland help to elaborate on, and ground, what is to be found in the text in such a powerful way that people think that Alice really is blond when, in fact, Carroll does not actually specify the color of her hair in the book.

Pieces of text, then, can simplify, complicate, elaborate, amplify, confirm, contradict, deny, restate, or help to define different sorts of meanings when they interact with images and objects. This can occur in cartoon strips, in photographs with captions, in maps with place names, in advertisements with overlapping text, in ready-to-assemble furniture with instructions, or in the case of sculptures that have written provenances.

FUNCTIONS

DO YOU KNOW WHAT I MEAN?

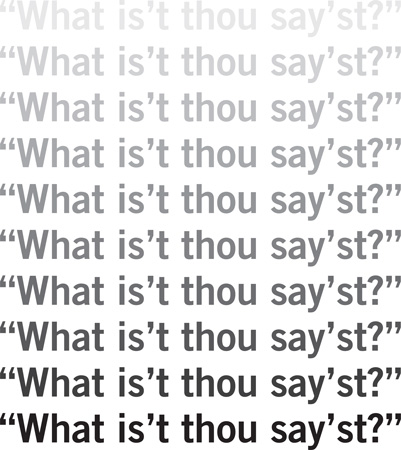

The meanings of words or sentences depend on the function they play in a language. Here are a number of different ways in which the words “What is’t thou say’st?” and “Do you know what I mean?” might function.

Emotive function. As producers of communication we often reveal things about our emotions (e.g., hopes, fears, and feelings), our attitudes (e.g., beliefs, desires, and thoughts), and our age, status, gender, race, or class. By saying, “Do you know what I mean?” in an anxious way someone may indicate that they are nervous about their ability to communicate clearly. When language reveals some personal characteristic in this way it has an emotive function.

Conative function. Communication will always have an effect on the people or persons receiving it. In this instance, someone who says, “Do you know what I mean?” all the time may simply bring about a feeling of irritation in the listener.

Referential function. When we utter the words “What is’t thou say’st?,” the words themselves may not matter. What may matter instead is how the words are used to create a particular form of reference. In this instance, they may refer to the language of Shakespeare, which is where they come from.

Poetic function. The poetic function is not so much about poetry as about the creativity or aesthetics of language use. So one difference between “What are you saying?” and “What is’t thou say’st?” is that the latter form of expression seems to have an aesthetic quality that the former form of expression does not.

Phatic function. In using the phrase “Do you know what I mean?,” we could be saying “Are you listening to me?” In this instance, the content of the communication is redundant because the purpose is simply to keep the channels of communication open. When you want to maintain or establish communication with someone else, language can be used in a phatic mode to get attention.

Metalingual function. Sometimes we need to make sure communication is working properly. For example, if you are giving important instructions you may need to ask, “Do you know what I mean?” afterward. In saying this, the content of what you say matters because you are checking to see whether what has been said has been fully understood. In this case, the question has what we call a metalingual function.

FORMS

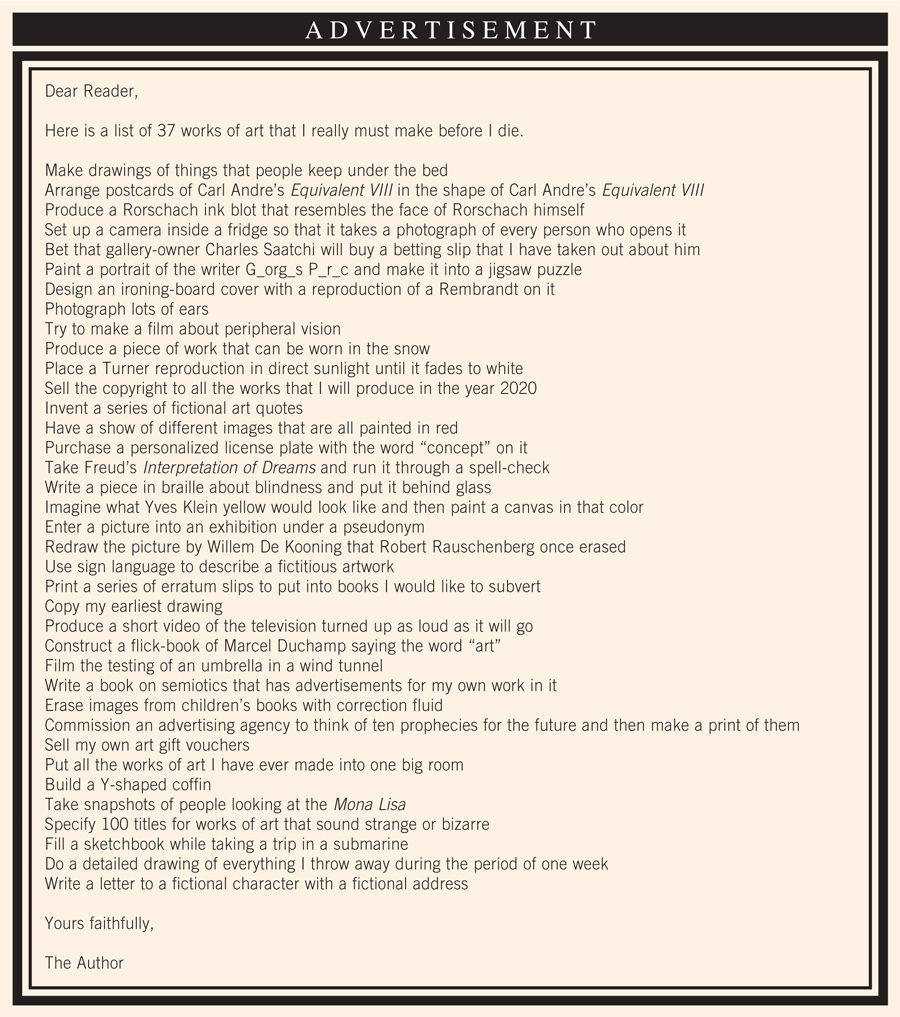

DO YOU NOTICE ANYTHING ODD ABOUT THIS ADVERTISEMENT?

Different relationships can be constructed between writers and readers—and speakers and listeners—by using different linguistic forms. Some of the many forms that speech and writing can take are listed below:

• Formal Writing: academic essays, legal forms, menus, instructions, medical reports, textbooks, memoranda, manifestoes

• Informal Writing: personal letters, e-mails, postcards

• Formal Speech: political speeches, scripted performances, academic lectures

• Informal Speech: casual conversations, improvised performances, practical seminars

Although these forms of speech and writing are often distinct, they sometimes converge. Converging forms are often employed by advertisers to create different kinds of relationships with consumers. Sometimes an advertisement will take the form of a letter. If such a letter uses a personal form, then this may help create a false feeling of intimacy between the advertiser and the person reading it. This false feeling of intimacy may be effective in disarming the reader. And this in turn may make the reader susceptible to the message that the advertiser is trying to convey.

In the text on the previous page I have used a number of conflicting formats. We are told at the top that it is an advertisement, but it also appears to be a letter in certain respects. It also has certain characteristics of a manifesto. At the same time the words “Dear Reader” and “The Author” appear on this notional page, which makes it look as though there is a recognition of the fact that the text in the box is being produced in the context of something else (for example, a book on semiotics). By combining various familiar written forms that usually have a definite structure, meanings may start to become opaque. However, by challenging existing linguistic structures there are still some advantages. One is that new meanings may evolve.

It may be of interest to note that the author is producing a limited number of prints from the piece on the previous page that will be sold independently as artworks.

PLACING

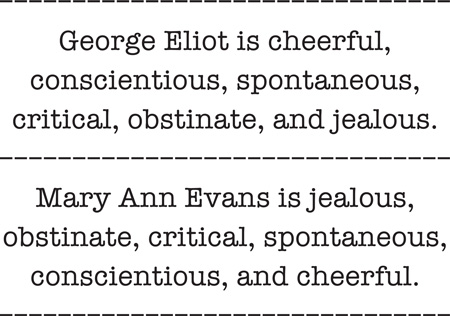

WHICH PERSON DO YOU LIKE BETTER?

Even though the descriptions are the same, the judgments we make about these people may depend on the order of the words used. Our attitudes in such cases result from what are called “serial position effects.” If you preferred George Eliot to Mary Ann Evans then that may be because the qualities listed at the start are easier to recall—because they are held for longer in our working memory—and hence they tend to have more impact on our thinking. This is sometimes referred to as the “primacy effect.” (It could be that certain clichés and stereotypes about women—namely, that they are likely to be more jealous and critical than men—could also influence us in a negative fashion in this instance.)

Our willingness to play with the placing of words and letters to create new and novel meanings is evident from many games and pastimes, from the crossword to the anagram or the palindrome. One way to generate new meanings is to splice two words together. For example, if we choose to splice the word “internet” with the word “intellectual” then we generate the new portmanteau word “internetual.” Having done that, we might seek a meaning for this word. In this case, the word “internetual” might refer to somebody whose, perhaps false, intelligence is gleaned exclusively from the internet.

The placing of words in a new or novel order may sometimes have the effect of shocking or surprising us. The method of cut-and-paste poetry is an example. This way of making poems was popular with the group of artists know as the Dadaists. One of them, Tristan Tzara, suggested that one method of making a poem was to find a newspaper and, having cut it up, to shuffle the pieces in a bag before drawing them out at random and making a note of the order in which they had been drawn, along with their content.

PROMINENCE

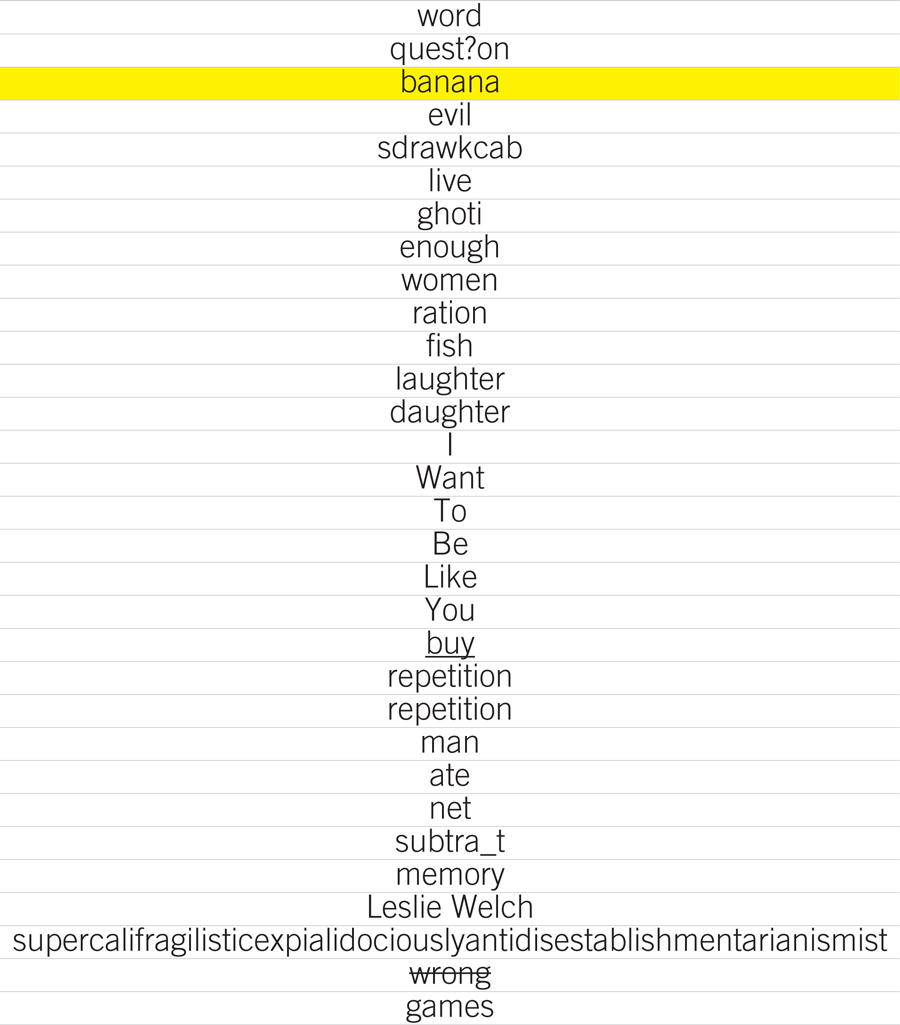

READ THE FOLLOWING LIST OF WORDS ONCE AND THEN TURN THE PAGE:

Try to remember as many of the words you have just read as possible. Which words did you remember? Which words seemed most prominent to you? Ask yourself why this is. Do we remember some words more than others because they have greater personal meaning for us? Or do we remember them because they are more unusual? Once you have thought about this issue you may read on…

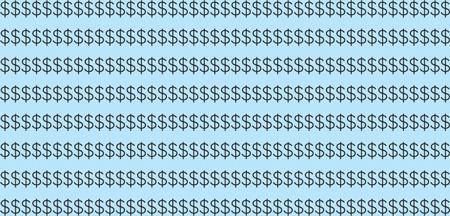

We often remember what happens at the beginning of a book, film, television program, or talk. These things tend to have prominence for us. What happens in the middle, however, tends to be more of a blur. Recent facts and events are also prominent in our minds. Could anyone forget the date 9/11? Things are also prominent when they are repeated, and repeated, and repeated, and repeated, and repeated, and repeated, and repeated, and repeated, and repeated, and repeated, and repeated.

If something is PROMINENT, for whatever reason, it will tend to be remembered.

The same is true of things that have a pattern.

Texts of various kinds can be given prominence by all of these things. The problem with trying to create textual prominence though—and giving prominence to something is really a way of highlighting certain meanings and indicating that they are more important than others—is that it often has to be done against something that is not prominent. That is why things that are exciting—whether they are objects, images, or texts —may only exist when there is a contrast with things that are not exciting.

Remember that what happens at the end of a book, film, television program, or talk will also tend to be more prominent in your mind than what happens in the middle of it.

VOICES

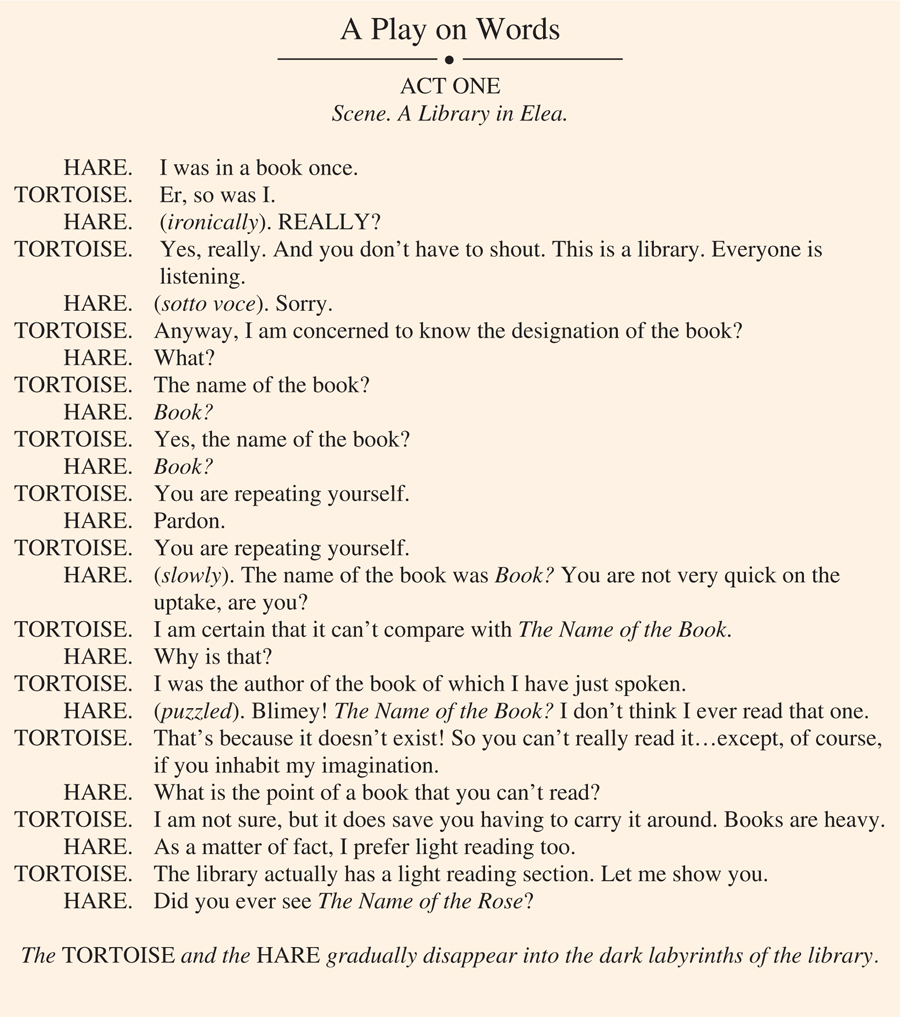

HOW LIKE REAL SPEECH IS THIS DIALOGUE?

Textual meaning is read and understood in various ways depending on how it looks (its graphological features), how it sounds (its phonological features), and what it means (its semantic features). Some examples from the previous page are given in square brackets:

Personal pronouns. Using “I” is helpful if you want to create a personal feeling to the text. This also helps to individualize the speaker. Using “we,” on the other hand, has connotations of group definition and territoriality. [“I was in a book once.”]

Prosodic features. These are aspects of stress and intonation. They can be represented by typographical features such as different typefaces (e.g., size and shape), simulated handwriting (e.g., via different stylistic features), and by aspects of punctuation (e.g., italics and exclamation marks). [REALLY?]

Fluency and nonfluency features. Fluency concerns the extent to which the language flows; nonfluency concerns the extent to which it does not flow, but stutters and hesitates...[“So you can’t really read it…except, of course, if you inhabit my imagination.”]

Accent. Accent is often obvious in spoken language, although it may be suggested in written language by an alteration in standard spelling. [“Blimey!”]

Vocabulary. Vocabulary, whether from everyday conversations or regional accents, can show the age, gender, social class, and ethnicity of the persons involved. [“Anyway, I am concerned to know the designation of the book?”]

Repetition. Repetition is often used to emphasize points in stories (particularly those for children), advertisements, and political speeches. [HARE. Book? TORTOISE. Yes, the name of the book? HARE. Book?]

Grammar. Grammar, which concerns the way in which the sentences are constructed, may also be indicative of age, gender, social class, and ethnicity of the persons involved. [“I was the author of the book of which I have just spoken.”]

Interactive markers. Overlaps, interruptions, reinforcements that indicate understanding (or a lack of it), noises such as “er,” “mm,” “um,” “oh,” “yeah,” “ugh,” “eek,” and “aargh,” and monitoring expressions (phrases such as “you know”) are all interactive markers. [“Er, so was I?”]

Topic changes. Topic changes are often evident in both written and spoken language. [“TORTOISE. The library actually has a light reading section. Let me show you. HARE. Did you ever see The Name of the Rose?”]

INTERTEXTUALITY AND INTRATEXTUALITY

COULD THIS BE TRUE?

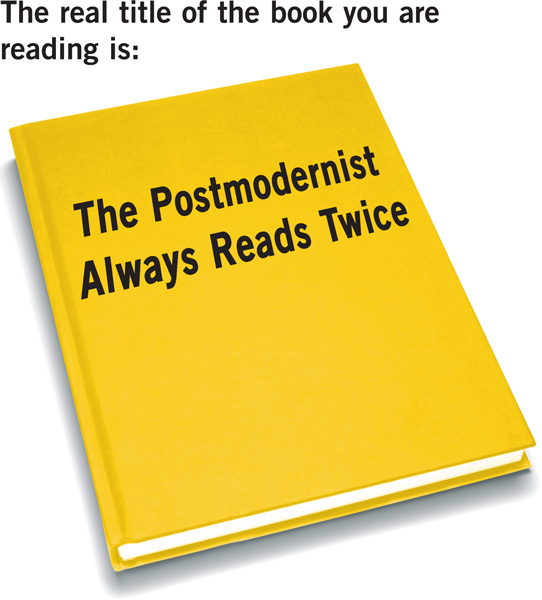

The Postman Always Rings Twice is a film that was first made in 1946. I have used the title The Postmodernist Always Reads Twice because postmodernism is partly about how works cannot be understood in isolation from one another, but only with reference to one another.

“Intertextuality” is the word that is used to describe how works of various kinds (e.g., books, paintings, sculptures, designs, advertisements etc.) make reference—often in clever ways—to other works (i.e., other books, paintings, sculptures, designs, advertisements etc.). It also describes how the various meanings that these works create are interrelated. This can happen through translation, parody, pastiche, plagiarism, allusion, homage, echo, quotation, recycling, spoof, sequel, prequel, and remake. The references that works make to one another are often exemplified in terms of structure (e.g., the layout of one book might be copied from another book) or in terms of content (e.g., the plot, or else the names of the characters, might be the same).

“Intratextuality,” on the other hand, is used to describe the internal relationship between different parts of the same work. This can involve such things as the relationship between two chapters in the same book, between two people depicted in the same painting, or between two or more objects that form the same collection.

When it comes to the supposedly “imaginary” title of this book, knowing about the existence of this film enables you to understand the reference that is being made. And once you know where this “imaginary” title originates from, and why postmodernism is about how we understand the world through multiple references, you start to realize that there is not one way of reading and understanding such an “imaginary” title. In this way, you may come to appreciate the self-referential joke that I have tried to make. Or is it a joke?

PARATEXT AND PARALANGUAGE

WHAT IS A PARATEXT?

WHAT IS A PARALANGUAGE?

Titles, dedications, acknowledgments, blurbs, epigraphs, prefaces, introductions, footnotes, illustrations, marginalia, erratum slips, endnotes, and indexes all count as paratexts. Paratexts stand outside the main body of a work and comment on it, or alter the meaning of it, in some way. The power of paratexts to change the meanings of texts can be seen if we consider the erratum slip. Suppose you are consulting a book on mushrooms. You are hoping to discover which mushrooms are good to eat from your local woods. However, an erratum slip falls from the book that says, “Page one, paragraph two, line three, should read: ‘The False Morel mushroom is deadly.’” This erratum slip does more than correct an error. It undermines the whole book because if the author or publisher cannot get the facts right on the first page we may wish to conclude that the pages that follow will also be strewn with errors.

The paralanguage is about the nonverbal aspects of communication that work alongside, surround, or support a given text. These nonverbal aspects of communication may serve to support or modify the meaning of the main text. For instance, when we encounter a person speaking or reading from a book we have to attend to what he says, but also to his bodily position and posture, facial expressions, the gestures that he makes, the physical proximity that he has to ourselves, the clothing he wears, and whether he has established eye contact with us. In addition, we might note his tone of voice and any speaker effects that are in evidence, such as whether the piece of communication is accompanied by laughter or sadness. In other words, while we may identify a particular text as the central locus of meaning, there are things that stand outside any given text that can influence, and change, the way that we understand and interpret it.