7

FRAMING MEANING

Starting with different units of meaning, this chapter will build a framework that will allow us to understand communication in terms of the wider context of society and culture. The notions we will examine are as follows:

Semantic Unit | = The thing that expresses meaning |

Genre | = The category of expression |

Style | = The manner of expression |

Institution | = The place or site of expression |

Stereotype | = The norms of expression |

Ideology | = The ideas and values that are employed to justify, support, or guide expression |

Discourse | = The uses of expression that create or reflect different aspects of the social order |

Myth | = The stories that represent and shape individual or collective expression |

Paradigm | = The systems of thinking that configure expression |

In order to understand how objects, images, and texts fit with the groupings we have just defined, I have given some examples of their application below:

Chair (Semantic Unit)

Office furniture (Genre)

Functional (Style)

Store (Institution)

An object with a standard seat, four legs, and a back (Stereotype)

Consumerism (Ideology)

Need (Discourse)

Practicality (Myth)

Modernism (Paradigm)

We can explain this example quite simply. A chair (Semantic Unit) might be a piece of office furniture (Genre) that is practical, with an appearance that is functional (Style). Thanks to the exclusive emphasis on function, this type of furniture may be rather bland (Stereotype). Purchased from a store (Institution), this piece of furniture might be viewed in the wider context of consumer society, one where the value of buying and selling goods seems obvious to everyone (Ideology). In terms of justifying this purchase, we might talk about the need to avoid backache (Discourse) because of the long periods sat at our office desk. Here, the language of practicality (Myth) might also be invoked. Finally, our understanding of the piece of furniture in question may be framed by the epoch that contributed most to functionality and practicality in design, namely Modernism (Paradigm).

The concepts we have articulated apply equally to images and texts. Here are two more examples:

Portraiture (Genre)

Academic (Style)

A lifelike depiction of a sitter (Stereotype)

Gallery (Institution)

Naturalism (Ideology)

Objectivity (Discourse)

Genius (Myth)

Realism (Paradigm)

A painting (Semantic Unit) might be a portrait (Genre), executed in an academic manner (Style), with a corresponding attempt to be lifelike in its execution (Stereotype). Exhibited in a gallery (Institution), the picture might present itself as a naturalistic and detached view of the sitter (Ideology). The description that accompanies the picture might speak of the objectivity of vision (Discourse), the rare talent and skill of the artist who carried it out (Myth), and the tradition of realism in which it should be viewed (Paradigm).

Book (Semantic Unit)

Children’s story (Genre)

Informal (Style)

The fairy tale (Stereotype)

Library (Institution)

Educational (Ideology)

Learning (Discourse)

Innocence (Myth)

Victorianism (Paradigm)

A book (Semantic Unit) might be a children’s story (Genre), written in an informal fashion (Style). It could be a familiar fairy tale (Stereotype), and it might be borrowed from a library (Institution). The jacket of the book could highlight the educational opportunities that the reading of the book affords (Ideology) and in so doing describe the moral lessons that may be learned from it (Discourse).

The parent reading the jacket of the book may interpret its content in terms of childhood innocence (Myth), and by way of certain received Victorian ideals concerning the purity of youth (Paradigm).

The context that helps us to situate and provide the meaning for a given semantic unit may not always be as straightforward as these examples might imply. This is because two genres may have coalesced in a single work (e.g., romance and comedy in film); the style of a piece may be reinterpreted as it starts to date (e.g., 1920s clothing now looks quaint); the stereotype of something may have become more well known (e.g., the brutalist tower blocks of the 1960s); and the location of an object may have shifted (e.g., a classic chair may have moved from a home to a museum). Moreover, when we try to make a judgment about meaning we could find that ideologies may be competing, that discourses may be overlapping, that myths may be evolving, and that alternative paradigms may be coexisting; all of these could serve to alter the interpretation we assign to the particular work we have chosen to study.

The exact details of the context for a particular semantic unit, then, is vital to appreciate and understand if meaning (or possible meaning) is to be forthcoming. This is because when a context for a specific semantic unit is misdescribed, underdescribed, or simply missing, our ability to engage in an analysis of it will be impaired. Of course, the idea that a given semantic unit may have a final and complete context that is free of any possible confusion as regards its meaning is one that we should perhaps reject. The reason for this is that new times will always provide for the possibility of new contexts and therefore new interpretations. New interpretations that enable us to view a piece of work in a fresh way must always be welcome, particularly where those interpretations help to invigorate our experiences or strengthen our understanding.

SEMANTIC UNITS

HOW SHOULD WE JUDGE THIS IMAGE?

Semantic units are discrete items of communication that have actual and potential meanings. A semantic unit is an aspect or part of a thing, a thing itself, or a collection of things that can be identified as distinct elements of communication.

Text-based semantic units are the easiest to identify: they consist of words, sentences, paragraphs, pages, chapters, or books. We know this because when we are unable to understand a particular textual element we can ask: “What does this particular word/sentence/paragraph/page/chapter/book mean?”

With images, the issue is more difficult. A painting can have brush-marks, lines, tones, textures, colors, and different parts, all of which can be identified as meaningful—of course the picture as a whole has a meaning too. Once again, we can identify the semantic unit in question by picking out that which is not understood by asking: “What does this particular mark/line/tone/texture/color/part of the image/whole image mean?”

Parts of objects, objects themselves, and collections of objects can be thought of as semantic units too. In this instance, when we are mystified we might ask: “What does this part of the object, this whole object, or this collection of objects mean?”

One problem with semantic units is in knowing exactly where one begins and the other ends. This might happen, for example, in a case where there seem to be two individual photographs that completely overlap (as on the previous page). Here we have two choices. Either we can treat the image as a mistake and try to read each of the semantic units of which it is composed separately, or we can treat the image as a whole semantic unit and assign it a single set of meanings. Which option we choose in this case may depend on what we think was the intention of the photographer.

For the purposes of this chapter we will look at semantic units as complete things (e.g., books, paintings, chairs), while tending to ignore the problem of parts, collections, and the issues of overlap.

GENRES

IS THIS A LANDSCAPE OR A PORTRAIT?

Genres are categories that conform to a certain division or subdivision of a particular medium. Design has the genres of graphics, multimedia, furniture, product, industrial, domestic ware, textiles, and fashion. Magazines have the genres of advice, entertainment, information, and instruction. Television has genres of news, soap opera, education, and comedy. Books have the genres of the novel, the diary, biography, history, and poetry.

The genres just listed can obviously be further divided— though whether we want to say that the divisions are themselves genuine genres is open to debate. Furniture design can be for the home, work, or leisure. Magazines can offer advice that is serious or light. Television news can be factual or anecdotal. Poetry books may be confessional or descriptive.

Each semantic unit, whether object-, image-, or text-based, will often be communicated through a well-established genre. The genre chosen will tend to set up a series of codes that allow the communicative act to take place successfully. These communicative acts will often only be truly productive when they conform to the rules of the genre in question (i.e., when there is some shared understanding of what the genre requires). One of the rules of film is that there cannot be a change of genre halfway through. For example, a science fiction film should not suddenly change in the middle to a western. Making this switch is forbidden because it would confuse the audience. The same is true of a news report that starts with some serious event and ends with a piece of gossip.

The painting by Thomas Gainsborough of Mr. and Mrs. Andrews (c. 1750) on the previous page presents us with an apparent exception to this rule in that it appears to combine portrait and landscape. So why is this allowed? The obvious answer is that the picture depicts a moment where two genres coalesce. In this sense it is rather like the way in which some films combine the genres of romance and comedy. What this shows is that a single semantic unit can contain melded genres but not genres that are sequential.

STYLES

WHAT KIND OF PERSON HAS WRITTEN THIS SENTENCE?

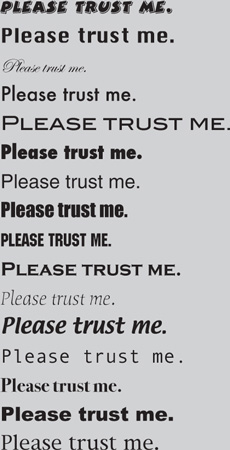

A style is a manner of doing something. The style in which something is done can influence how a message is received. This is true of the sentence on the previous page. The elegant typeface in which the sentence “I am not a criminal” is written seems to make it more believable.

When it comes to message-making we should not forget that the form of the message matters as much as the content. To demonstrate this point, compare the following examples:

What is remarkable here is just how much the style of typeface can influence how we feel about the sentence.

Different styles can be exemplified in writing, painting, designing, dressing, acting, walking, talking, and even thinking. If we undertake any of these activities then we will be sure to do so in a way that is distinctive and personal. It is always within our power to develop our own particular and individual style of writing, painting, designing, dressing, acting, walking, talking, or thinking. At the same time, however, our own way of doing these things will tend to make reference to a more general way of doing them. In other words, while there are individual styles, these usually partake of styles that are social and cultural in origin. Thus, the way in which we talk will not be independent of a community of people who talk in a similar way, for example in terms of accent. The accent that you have will always be a cultural and stylistic variation of a particular language.

STEREOTYPES

WHAT MAKES THIS WORK OF ART NONSTEREOTYPICAL?

A stereotype is a generalized idea of something. There can be stereotypes of different kinds of objects, images, texts, animals, plants, people, or groups of people. These stereotypes often derive from certain observations, thoughts, or prejudices that may or may not be grounded in fact. For example, the stereotype of a woman car driver is of someone who lacks certain competences in driving. Yet the stereotype is not accurate. If it were accurate then insurance companies would be right to charge women more to insure their cars than men. What we find, however, is that men are charged more because in reality they tend to be less competent drivers than women.

Stereotypes are sometimes helpful to us. They can give us a shortcut to understanding a certain thing or situation. At the same time, however, they tend to be rather inflexible and simplistic. We might think, for example, of an artwork in terms of certain stereotypical materials. Sculptures, for instance, tend traditionally to be made from stone, bronze, or wood. Sculptors of the twentieth century, though, broke away from these stereotypical materials and used such things as glass, plastic, concrete, and even waste.

Carl André’s Equivalent VIII is an example of what is called Minimalist sculpture. It consists of two piles of ordinary bricks laid out in an oblong. One might say that it provides a challenge to the stereotype of what sculpture is, but also to our notion of how art is valued (not least because the Tate Gallery in London paid $12,000 to buy it in 1972). Another answer as to what makes it nonstereotypical is that it is made from everyday materials. (Though in recording these answers we might also wonder whether the assumption that the question makes, namely that this is a genuine work of art, is right in the first place.)

INSTITUTIONS

HOW MIGHT THE DISPLAY OF AN OBJECT INFLUENCE HOW WE FEEL ABOUT IT?

As institutions, museums are characterized by the fact that they remove objects, images, and texts from the typical arenas of production, consumption, ownership, use, and exchange that they tend to inhabit. By making the museum into a sanctified zone for display, objects, images, and texts (i.e., various semantic units) are thereby abstracted from the concreteness of the social and historical practices in which they normally participate. The objects, images, and texts that are displayed in the museum are usually enhanced through the presentational codes of staging. By putting objects in glass cabinets, by raising sculptures on plinths, by putting pictures in ornate frames, by lighting books in a reverential fashion, by providing academic and quasiacademic forms of written information on invitation cards and labels, and in catalogs, leaflets, handouts, and pamphlets, or by simply placing rope around an area of display in order to cordon it off, the pieces on show are set apart from the spectator. And this in turn serves to remind the museum-goer of the sense of reverence that they are expected to have toward what has been put on display.

Just like the museum, other institutions act to regulate cultural meanings and the social behavior that goes with them. Churches regulate meanings and forms of behavior through their holy books, by designated areas of worship, and through the prescribed courses of action that go with the ceremonies that they have devised. Houses regulate meanings and behavior by the way in which such things as walls, windows, fences, doors, locks, bars, and other security devices are configured to create segregation. Courts of law regulate meanings and forms of behavior through the layout of their rooms and corridors (thus keeping lawyers, jurors, and the accused apart), and by rules of procedure (which dictate the formal modes of address that control the interactions between participants).

IDEOLOGIES

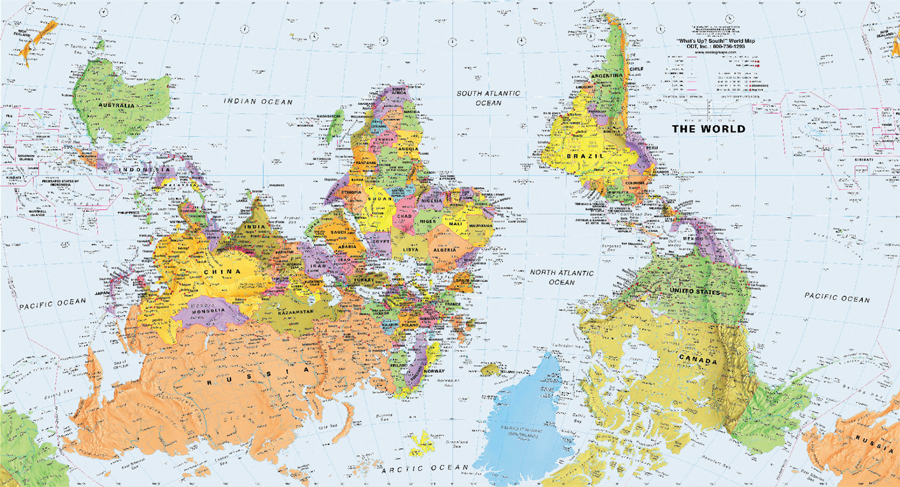

WHAT IS WRONG WITH THIS MAP?

On this “upside-down” map of the world Africa, rather than Europe, appears to be at the center. This makes it seem wrong, though in reality it is not wrong, but merely presenting an alternative view of things, or ideology, that may actually help us to see the world in a different way.

Ideologies are about ideas: what they are and how they are formed. Ideas are not natural. On the contrary, they arise from, and can be explained in terms of, particular forms of society and culture. The key question for those interested in ideology in relation to semiotics is just how our ideas fit into larger systems and structures of meaning that particular societies and cultures create and enforce. To answer that question, though, we need first to understand the various forms that ideology might take. Ideology might be understood as either:

1. A system of beliefs and desires that are characteristic of the value system of a particular class, group, or culture. Political beliefs tend to be like this. Thus right-wing ideology tends to place value on tradition, authority, and hierarchy, whereas left-wing ideology tends to place value on equality, liberty, and community.

2. A system of illusory beliefs or desires that can be contrasted with beliefs or desires that are true. Marxists view ideology in this way. Thus Marxists argue that by the propagation of certain ideas the working class is tricked into accepting an economic and social order where the upper class is in charge.

3. The general process through which our systems of belief and desire are produced and consumed. On this view, various parts of a society or culture act to produce (and also make available to consume) certain styles of thought or ways of thinking. For instance, popular newspapers tend to promote the ideology of the person who is of value to society just because they are rich or famous.

DISCOURSES

WHAT DOES THIS THRONE SAY ABOUT THE PERSON WHO MIGHT SIT IN IT?

Discourse analysis tends to focus on language and the contexts of its meanings, but objects (and images) set up and sustain discourses of their own. For example, the throne of a king (like the one on the previous page) sets up its own discourse. It is a discourse that is meant to give authority and status to its user.

In general, discourses help to form our ideas about the world through regulated forms of use. Discourses consist of different areas of knowledge, norms of “lived” experience, structures of organization, systems of regulation, and kinds of identity. Discourses set the boundaries of these things through established forms that create or reflect particular aspects of society and culture. For example, there are professional discourses (evident in the expert languages of law or medicine), discourses of competition (prevalent in Western ideas of economics and political economy), discourses of solidarity (made manifest through various religions and via the idea of a nation state), discourses of learning (manufactured and sustained by established education systems), discourses of sexism (palpable in the expressions, both verbal and visual, of individuals who think that men are superior in some way to women), and many others, all of which both shape and replicate our attitudes to different people, styles of living, institutions, objects, images, and texts.

Take the discourses of cleanliness (which partake of the more general discourses that focus on health) as an example. The discourses of cleanliness, which since the Victorian period have been prevalent in Western culture, are promoted in different ways and through different media (e.g., educational leaflets, television news stories, housekeeping books, tips in glossy magazines, and advertisements for cleaning products). These discourses act in different ways, and through different media, to make what is known—that cleanliness is important for sustaining good health—seem to be simply a matter of common sense. Indeed, this is the aim of all dominant discourses: to make what is a cultural and societal product seem to be natural and self-evident.

MYTHS

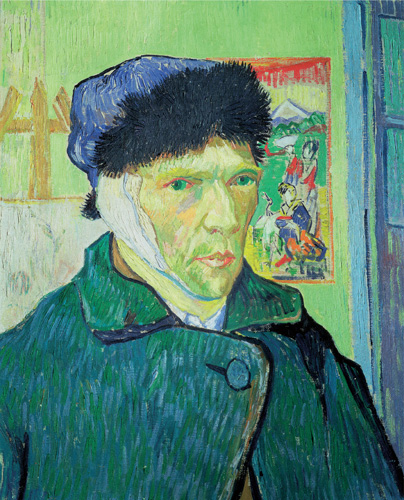

DO THE LIVES OF ARTISTS INFLUENCE HOW WE SEE THEIR PICTURES?

Myths help us to understand the world. We tend to think of myths as being ancient stories that are probably not true. But in the more general sense a myth may be considered true, partly true, or else simply false. It all depends on the myth in question and the function that it serves. There are numerous kinds of myth. There are urban myths (stories that, whether true or not, are supposed to give us some moral insight), product myths (products that, whether they really do so or not, are supposed to bring us such things as health, wealth, or happiness when we purchase them), and image myths (images that, whether they really do so, appear to enhance our social standing or the social standing of others). There are also more specific myths: the myth of childhood (the idea that our youth was a time of innocence, naturalness, and freedom); the myth of the self (the idea that the self is a single thing that has its very own distinctive thoughts, beliefs, and desires); and the myth of the countryside (the idea of a place where we can experience unadulterated nature). Other myths that dominate contemporary society include the myths of science, politics, religion, design, art, and the lives of the rich and famous.

One of the most interesting myths is that of the artist. The lives of artists are often seen as dramatic. This is particularly true of Vincent van Gogh. We think of him in poverty, we contemplate his fatalistic love affairs, we speculate about the severing of part of his ear, and we wonder over his mental turmoil and final death. All these biographical details cannot fail to influence how we view his work as they all go to form the myth of Van Gogh. However, imagine that out of the blue someone discovers that these details are untrue. Van Gogh, it turns out, lived a blissfully happy life. Would this be enough to change the myth and hence the meanings of all of his pictures? In particular, would you then view the painting on the previous page as something other than melancholic?

PARADIGMS

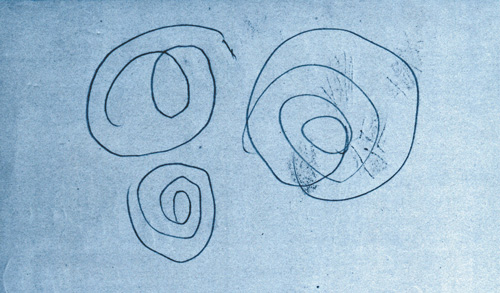

WHAT DO THESE DOODLES MEAN?

Sigmund Freud made these doodles. Once you know this do you see them in a more Freudian way? We know that Freud emphasized the importance of hidden desires. Therefore, maybe he was expressing his own hidden desires when he made these doodles.

In general, our readings of objects, images, and texts are framed by what we call paradigms. A paradigm is a way of seeing the world through a highly structured framework of concepts, procedures, and results. And so, given that Freud made these doodles, what we see in them may be structured by particular Freudian concepts (e.g., the unconscious, the psyche), procedures (e.g., the process of analysis), and results (e.g., the identification of a complex or phobia). In particular, these drawings appear to show spirals that are descending. For this reason they might represent a journey into the depths of the mind itself, or they may say something about Freud’s own subconscious fear of falling into some hole or recess. Perhaps they indicate a fear that is sexual in some way.

Now suppose that these drawings were not by Freud. Instead, imagine that they were by Albert Einstein. Would that change how you read them? If you think it would, then is this because you would start to apply a different set of concepts, procedures, and results to them (i.e., those that you associate with the work of Einstein)? Such a radical alteration in your perception is called a paradigm shift. A paradigm shift happens when an alternative way of thinking is provided by a new set of concepts, results, and procedures. The change in perception takes place due to the new framework or theory that you now use to interpret your experience.

A paradigm shift in this instance would take place if you shifted your interpretation from a Freudian one to an Einsteinian one.*

*Freud did, in fact, draw these images.