Creating tokens in an ICO, as covered in Chapter 4, Token Varieties, was one thing, but figuring out how many to create, how much to sell, the early round bonuses, the inflation rate and everything else relating to the mechanics of the tokens was (and still is) a challenging task. All of the above had to be communicated to supporters and investors, while trying to keep things simple.

Although there was no right or wrong way to create tokens and market them, a lot of parallels can be drawn from the issuance of regular shares in a company, served with a side of economic incentives, a sprinkling of game theory, and a dust of creative marketing.

In this chapter, we will look at:

- Token supply and distribution

- Presale strategy and bonuses

- Hard cap, soft cap, and no cap

- A reverse Dutch auction

- A token mechanic blueprint

If a lawyer was important when contemplating an ICO, a CEO or Chief Economic Officer was becoming crucial when looking at structuring the inner workings of one. Of course, what really happened was that many people quickly upskilled in the basics of monetary policies, such as the model for token supply and issuance, along with fiscal policy, such as how the funds would be spent. We will first take a look at the all-important supply and distribution of an ICO.

Looking at the number of tokens created, there was generally no rhyme or reason for the values chosen. The standard default in the early days seemed to be 100 million tokens, which was a nice round number. Others preferred a billion as a round number. The supply ranged from 2.6 million to 2.7 quadrillion:

|

ICO |

Amount |

|

Counterparty |

2.6 million |

|

Factom |

8.8 million |

|

Gnosis |

10 million |

|

Augur |

11 million |

|

Decent |

73.3 million |

|

Bancor |

79.4 million |

|

Firstblood |

93.5 million |

|

ICONOMI |

100 million |

|

MobileGo |

100 million |

|

Waves |

100 million |

|

Ark |

125 million |

|

TenX |

205.2 million |

|

Pillar |

800 million |

|

Humaniq |

921 million |

|

Synereo |

949.3 million |

|

Civic |

1 billion |

|

Nxt |

1 billion |

|

SingularDTV |

1 billion |

|

BAT |

1.5 billion |

|

Filecoin |

2 billion |

|

Ripple |

100 billion |

|

Kin |

10 trillion |

|

IOTA |

2,780 trillion |

Table 1: Examples of token supplies from various ICOs.

The reason why some of the supplies were not whole numbers was due to the sales model employed by various ICOs. For example, TenX did not select a fixed number of PAY tokens but instead chose a 200,000 ETH target and issued 350 PAY tokens for every 1 ETH. It also provided bonuses for earlier contributors, so when the calculations were done, a non-round number eventuated.

When deciding on a token supply, anything goes, but there are a few things to keep in mind. If it is set too low, your users may have to start working with fractional amounts and humans prefer to work with whole numbers. Also, consider that a proportion of tokens will be lost, which will reduce the overall supply. This can occur due to users losing private keys or tokens being sent to wrong addresses, which may make them unspendable forever.

On the other hand, creating something like 2.7 quadrillion tokens seems overly excessive. Firstly, large numbers become hard to read, say or comprehend. How many zeros does a quadrillion have again?

Secondly, having too large a supply tends to reduce the perceived value of the token. It is also not a good signal to the market. Scarcity is what helps to create value, not abundance, and in some cases, it is used as a marketing tool when dealing with investors.

As we can see above, several ICOs have used tokens in the billions, such as Civic (1 billion), Filecoin (2 billion) and Ripple (100 billion), which has been the upper range, if IOTA and Kin (10 trillion) are considered as outliers.

Tip

One thing to note when choosing a supply is divisibility. Although Ripple (XRP) may have 100 billion tokens, each token is divisible to six decimal places, so 1,000,000 drops make 1 XRP. This is the equivalent of 100 cents making 1 dollar. Bitcoin, however, has 100,000,000 satoshis in 1 bitcoin. Therefore, on the surface, it may seem that there are 4761 times more XRP than BTC (100 billion divided by 21 million), but the reality is that there is only 47.6 times more.

Token distribution started with the majority being made available to the public. This was the ideal scenario, as having the tokens held by as many avid supporters as possible was the goal. However, over time, the number dropped from the 80% mark to 70%, then 60% and then lower:

|

Aug 15 |

Feb 16 |

Apr 16 |

Aug 16 |

Sep 16 |

Nov 16 | |

|

Augur[1] |

Lisk[2] |

Waves[3] |

ICONOMI[4] |

Synereo[5] |

Golem[6] | |

|

Public* |

80% |

85% |

85% |

85% |

18.5% |

82% |

|

Developers/core team/founders |

16% |

7.8% |

9% |

8% |

10% |

6% |

|

Foundation |

4% |

12% | ||||

|

Strategic partners/advisors |

2% |

4% |

2% | |||

|

Early supporters |

1% |

1% |

17.5% | |||

|

Campaigns/bounties |

4% |

1% |

2% |

11.5% | ||

|

First-day ICO participants |

0.2% |

Table 2: Token distribution for ICOs from August 2015 to November 2016

* Public is the portion that is sold to buyers. The others are allocated, given, or distributed.

|

Apr 17 |

Apr 17 |

May 17 |

Jun 17 |

Jun 17 |

Jun 17 | |

|

Gnosis[7] |

MobileGo[8] |

BAT[9] |

Bancor[10] |

Status[11] |

Civic[12] | |

|

Public |

5% |

70% |

66.6% |

50% |

41% |

33% |

|

Developers/core team/founders |

95% |

13.3% |

10% |

20% |

34% | |

|

Foundation |

30% |

20% | ||||

|

User growth/community/bounties |

20% |

20% |

33% | |||

|

Future stakeholders |

29% | |||||

|

Status genesis token holders |

10% |

Table 3: Token distribution for ICOs from April 2017 to June 2017

Gnosis only made 5% of tokens available to the public, but this was due to the mechanics of its reverse Dutch auction (which will be explained later). Status distributed only 41% of tokens to the public but has since reserved 29% for future stakeholders:

|

Jul 17 |

Aug 17 |

Sep 17 |

Sep 17 | |

|

Pillar[13] |

Filecoin[14] |

Kin[15] |

Kyber Networks[16] | |

|

Public |

72% |

70% |

10% |

61.06% |

|

Developers/core team/founders |

10% |

30% |

19.47% | |

|

Foundation |

5% |

60% | ||

|

Company |

10% |

15% |

19.47% | |

|

User growth/community/bounties |

3% | |||

|

Future stakeholders | ||||

|

Status genesis token holders | ||||

|

Later funding |

15% |

Table 4: Token distribution for ICOs from July 2017 to September 2017

Kin provided only 10% of tokens to the public. This was very surprising and yet it still managed to raise just under $100 million USD. Its reasoning was outlined in its white paper:

"In order to finance the Kin roadmap, Kik will conduct a token distribution event that will offer for sale one trillion units out of a 10 trillion-unit total supply of kin. The proceeds of the token distribution event will be used to fund Kik operations and to deploy the Kin Foundation. A portion of the funds raised in the token distribution will be used to execute upon the roadmap of additional feature development planned for the Kin integration into Kik." (https://kinecosystem.org/static/files/Kin_Whitepaper_V1_English.pdf).

Kik pre-allocated another three trillion kin to the founding members and placed the remaining six trillion kin under the control of the Kin Foundation.

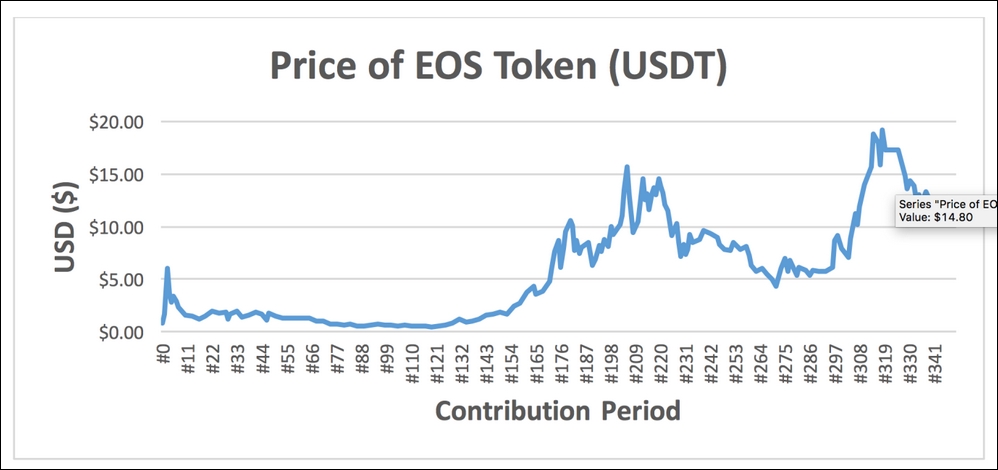

The EOS ICO was unique and deserves a special mention. The concept was that one billion EOS tokens were to be distributed over a period of 341 days. 200 million or 20% were distributed during the first five days, from June 26, 2017, to July 1, 2017, and an additional 700 million EOS tokens were distributed in two million blocks every 23 hours thereafter. 100 million or 10% was reserved for Block.one, an open source software publisher specializing in high performance blockchain technologies (https://block.one/about/).

Note that the vesting period of the 100 million for Block.one is 10% over 10 years. At the end of the five-day period and at the end of each 23-hour period, a fixed number of tokens were distributed proportionally amongst all the investors, based on their contributions. In other words, everyone in a specific period gets the same amount of EOS per ETH as everyone else. You only know for sure exactly how many EOS you are getting for your sent ETH once the period is over.

The EOS token purchase agreement provides a simple example (https://eos.io/documents/block.one%20-%20EOS%20Token%20Purchase%20Agreement%20-%20September%204,%202017.pdf):

- 20 EOS Tokens are available during a period.

- Bob contributes 4 ETH and Alice contributes 1 ETH during the period. The period ends.

- As a total of 5 ETH were contributed for 20 EOS Tokens during the period, 1 EOS Token will be distributed for every 0.25 ETH contributed. Therefore, Bob receives 16 EOS Tokens and Alice receives 4 EOS Tokens.

What was interesting was that all tokens from past periods were tradable and entered the public markets. This meant that there were two ways of getting EOS tokens: directly from the ICO or from previous ICO participants. It provided some interesting trading and arbitraging opportunities.

It didn't make sense to contribute to the ICO if the price was cheaper on the exchange, but it wasn't possible to know the final price until the contribution period was over. What some traders did was exercise a function within the smart contract called buyWithLimit(). The idea was to allow investors to specify the exact contribution period and a maximum limit of ether, but traders used this function and applied this to the current contribution period and specified the amount of ether needed to make the purchase lower than the current market rate. The trader could then claim the tokens and flip them on an exchange. The trader needed to make the transaction at the last possible moment because that was when the most amount of information was available to make the best possible decision.

Other traders took this one step further and not only contributed at the end but also sent bogus transactions to flood the Ethereum network, to push out would-be contributors. The strategy was to contribute 5 or 10 minutes before the close of the period and then send bogus transactions with abnormally high gas fees. Transactions are usually processed in order of highest fees to lowest fees, so regular EOS contributions would be temporarily squeezed out, allowing the trader to make a profit by gaming the system.

EOS ended up raising $172 million USD in the first contribution period, which took place over five days, resulting in an EOS token price of $0.86 USD ($172 million USD divided by 200 million tokens). The cheapest price was $0.48 USD at contribution period #123, which occurred on October 26, 2017. The most expensive was $19.29 USD per token at contribution period #315, which occurred on April 28, 2018.

At the conclusion of the ICO on June 1, 2018, EOS ended up collecting around 6.5 million ether, which is around $4 billion USD. EOS holds the record for not only the largest ICO raised but also the longest running:

Figure 1: The price of the EOS token at each contribution period over 11 months (https://eosscan.io/)

In the beginning, everyone formed orderly queues and calmly sent funds to bitcoin addresses and smart contracts, but as the excitement grew, especially during the hype of 2017, tokens and cash were flying everywhere. This was primarily due to token holders doubling or tripling their investments in a very short space of time. In some cases, investors made ten times their initial investment in a matter of weeks or even days of the tokens listing on exchanges.

First, it was all about just getting the tokens. Then it became a race to buy the tokens first because bonuses were often linked to buyers in the first week or days or even the first "Power Hour." The next level was a pre-ICO, where a second smart contract would be created to handle the receipt of the funds. Then we saw private pre-ICOs before the pre-ICO. It was utter madness.

Let's start by understanding how bonuses worked.

Nearly all ICOs have some sort of bonus offering stage, but let's first take a look at the ones that do not. Civic is an identity verification service on the blockchain, co-founded by Vinny Lingham, who was one of the sharks on the TV show South African Shark Tank.

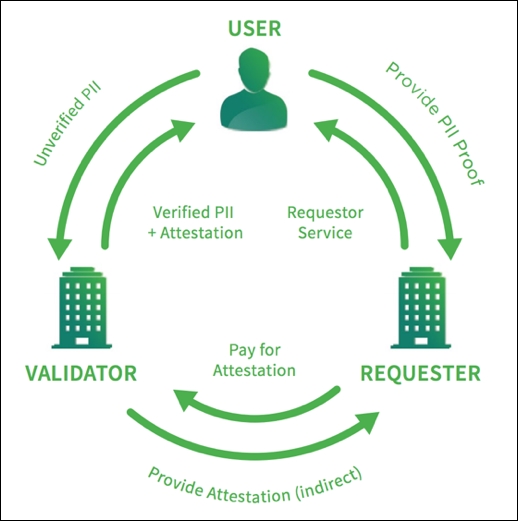

Civic's Secure Identity Platform (SIP) provides access to identity verification services that give businesses and individuals the tools to control and protect their identity. Individuals can access identity verification services by downloading the Civic App and setting up their digital identity by verifying their personally identifiable information (PII) with a trusted third party.

Additionally, Civic is spearheading the development of Identity.com, a decentralized identity ecosystem that will be completely open sourced, opening up access to secure, trusted identity verification services to people around the world.

The Civic App is designed to give users more control over when and where they share their personal data. A user's information is stored on the app, protected by biometrics and high-level encryption. Civic partners, called Requesters, can ask a user to provide verified personal information through custom QR codes. Once a user has unlocked the Civic App with their biometrics, the user can scan this code, review exactly which information is being requested, and choose whether to approve or deny the request.

The point here is that background and personal information verification checks may no longer need to be performed from the ground up every time that a new institution or application requires one, thus saving time and money.

Civic introduced a Civic token or CVC as a form of settlement and governance for participants in Identity.com. The user approaches a Requester to use a service or purchase a good. The Requester sends the user a list of Validators it accepts and the PII required. If the user has the required PII attested by a Validator, that is acceptable to the Requester, then the user selects to share that Validator's attestation with the Requester.

If the user does not already have a suitable attestation, then they will be asked to approach an acceptable Validator with unverified PII. Once the Validator is satisfied with the authenticity of the PII, it will attest to the accuracy of this information. This attestation, or digital fingerprint of the PII, is recorded onto a blockchain and the original PII is stored on the user's mobile device in an encrypted form.

The Requester and Validator mutually agree on a price for the attested PII. Once the price has been agreed, the Requester places CVC tokens into an escrow smart contract and the user sends the PII to the Requester. Once the PII attestation is received, the Requester inspects it and, if acceptable, provides the user with the desired service. In turn, the CVC tokens are released from the escrow smart contract and the Validator is paid in CVC. Therefore, Requestors pay for verification services with CVC, Validators are rewarded with CVC, and users are rewarded for sharing their information:

Figure 2: The interaction between users, "Validators," and "Requestors" in Civic's model (https://www.civic.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Token-Behavior-Model-May-16-2018.pdf)

The use of CVCs provides several advantages over an existing token or cryptocurrency. Firstly, it shields the ecosystem from extraneous considerations, such as volatility observed in other cryptocurrencies, and secondly, it makes it possible for the community to manage incentives to better control and drive the benefits of the ecosystem.

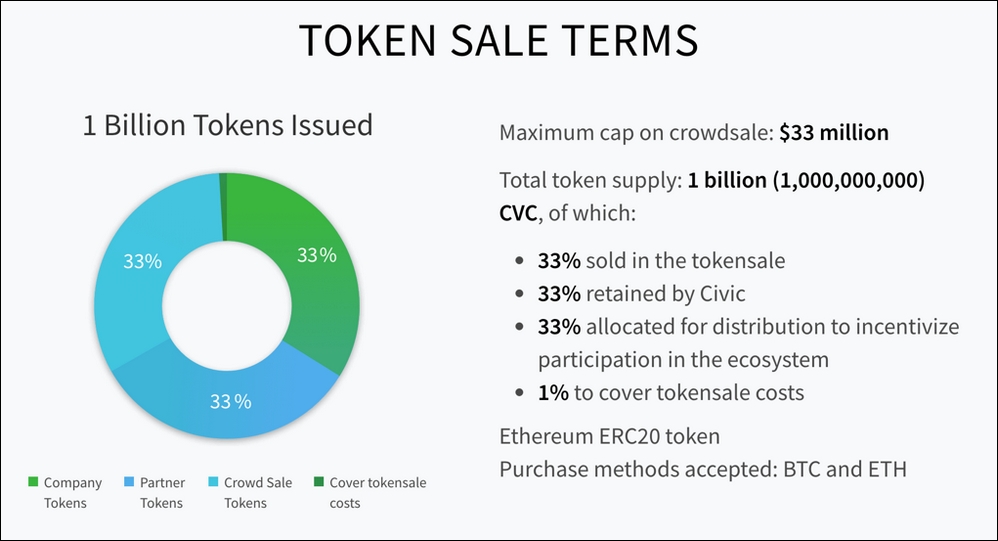

In its June 2017 token sale, Civic created one billion tokens: 33% were allocated to be sold to the public at $0.10 each, 33% were allocated for distribution to incentivize participation in the ecosystem, and 33% were allocated to the company. There was no bonus, meaning investors couldn't get more by purchasing early. In fact, this was prevented by a queuing system, where a random number was assigned to participants regardless of the order in which they arrived:

Figure 3: Civic's token sales terms (https://tokensale.civic.com/)

A bonus often helps to build momentum and attract buyers. Without a bonus structure, there is more risk that not all the tokens will be sold. To mitigate that risk and ensure that all 330 million tokens were sold, Civic held a presale for large buyers, with the provision that one-third of the tokens, or 110 million, would be available for sale during the token sale. This meant that if all 110 million tokens were purchased in the main sale, only 220 million would have been purchased in the presale. The idea here was to ensure that Civic received a much broader base of supporters to help kick-start the network. If, for some reason, Civic hadn't sold the full 110 million token allocation, then the bigger buyers would have effectively agreed to buy the difference. This meant that there were two ways that Civic's goal of ensuring all 330 million tokens were sold could be achieved. Clever!

Lingham explained Civic's strategy:

"We're creating a fixed supply of 1 billion tokens. We are pricing them at $0.10 each. We felt that we needed enough tokens to power the smart contracting system for years to come and we could go to 2 decimal places for fractional smart contract execution. 1bn felt like the right number — no crazy scientific reason here".

Civic announced that it had over 10,000 purchases and all had to be identified via Civic's own KYC (Know Your Customer) process, using the Civic App (https://www.ccn.com/civic-token-sale-concludes-earlysuccessfully-with-33-million-raise/). The goal was to provide the little guys with an even playing field against the big guys. The more people using CVCs, the better. That is why Civic aimed for broad adoption and support. In its own words, the company was chasing results and adoption instead of vanity headlines, such as being able to raise tens of millions of dollars in a matter of seconds.

Civic also kept the token price simple and straightforward throughout the process, at $0.10 USD. So, in the end, there was no complicated math for token allocation based on what day or week the tokens were purchased on, and most importantly, there were no discounts, which can often attract a different kind of buyer. These buyers are often speculators who do not plan to be users of the system and tend to dump their large holdings for profit shortly after the ICO.

At the Consensus 2018 conference in May, Civic debuted the world's first anonymous age-verifying beer vending machine in partnership with Anheuser-Busch InBev, the world's largest brewer. The vending machine displayed a QR code and anyone with the Civic App, that had verified their identity, could prove to the vending machine that they were over the age of 21.

Figure 4: The Civic vending machine on display at Consensus 2018

Although this was just a proof of concept, it was a user-friendly demonstration of Civic's identity verification protocol and just one of many potential use cases for identity verification services. Based on partial-knowledge proofs, the ability to anonymously perform age verification opens up new possibilities. This process is and will continue to be free for the end users, while Requesters are the ones responsible for paying for identity verification.

One year after its token sale, Civic's platform includes secure login, a reusable KYC solution and ID codes, a secure relationships verification service that enables anyone to securely verify a business, advisory, or investment relationship. Civic is also rapidly expanding its partner ecosystem with over 90 so far (https://www.civic.com/solutions/partners/).

The road ahead includes enhancing security capabilities and lowering barriers to entry, such as making transactions using fiat currency an option.

Kyber Networks also had no bonus structure. What it did have was a very cumbersome registration process. There was so much demand for its token, though, that it still met its cap of 200,000 ether, resulting in $48 million USD raised in 24 hours. Users had a seven-day window to be whitelisted. Whitelisting meant signing up to Slack, Telegram, or Wechat, which meant providing an email address, along with a full name, and other personal information. The next step was that the user had a 10-day period to register by going through a KYC process. A passport or national ID had to be provided to ensure one email and one Ethereum wallet address was linked to one real-world identity and that no one could game the system and register multiple times.

Figure 5: Kyber Networks' token purchase process (https://blog.kyber.network/kybernetwork-public-token-sale-901b3e7f5457)

Civic and Kyber Networks were exceptions because ICO bonuses were so popular that they were considered the norm. A common structure was to have a sliding scale early backer incentive mechanism or, in plain English, an early bird discount.

MaidSafe went with a 40% bonus for those who invested in the first week, a 30% bonus in the second week, 20% in the third week, and 10% in the fourth week (https://github.com/maidsafe/Whitepapers/blob/master/Project-Safe.md). Lisk and MobileGo followed a similar pattern:

|

MaidSafe |

Lisk |

MobileGo | |

|

Week 1 |

40% |

15% |

15% |

|

Week 2 |

30% |

10% |

10% |

|

Week 3 |

20% |

5% |

5% |

|

Week 4 |

10% |

No bonus |

No bonus |

|

Week 5 |

No bonus |

NA |

NA |

Table 5: Comparison of early buyer incentive schemes

The incentive for providing a bonus should be of no surprise. It was designed to reward early investors with more tokens, as they were taking on more risk. However, having too large a bonus appeared to be detrimental to the ICO because it was seen as devaluing the token. A balance had to be found.

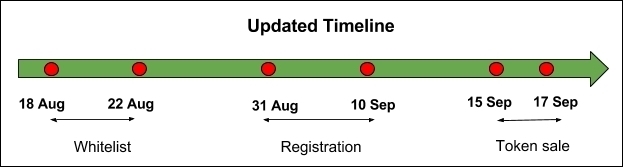

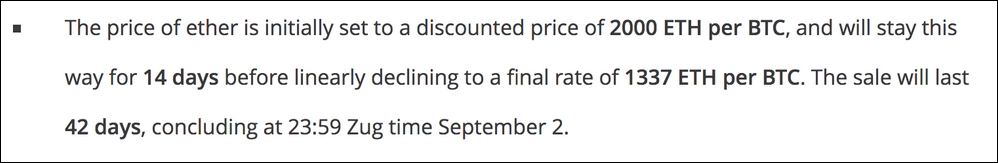

Ethereum had an incentive of one bitcoin buying 2,000 ether for the first 14 days and then it would drop 24 ether every day for the next 28 days. For example, on day 15, one bitcoin would only receive 1976 ether. The Ethereum team obviously had a good time playing with the numbers 1337 and 42.

Figure 9: The Ethereum ICO token sale details using key numerical figures of 1337 and 42 (explained in Chapter 4, Token Varieties) (https://blog.ethereum.org/2014/07/22/launching-the-ether-sale/)

Bonuses then got more creative and more convoluted. Waves provided a 20% token bonus on the first day, a 10% bonus for the next 17 days, and a 5% bonus for the first half of May:

|

Date |

Bonus |

|

12 Apr 2017 |

20% |

|

13–30 Apr 2017 |

10% |

|

1–15 May 2017 |

5% |

|

After 16 May 2017 |

No bonus |

Table 6: The Waves token bonus plan(https://blog.wavesplatform.com/waves-ico-structure-and-timeline-87db476cc586)

FirstBlood is a decentralized eSports platform built on Ethereum. It effectively lets players challenge each other using the platform token as a wager or betting system. The system uses smart contracts and decentralized oracles on the Ethereum blockchain. FirstBlood gave a huge 70% bonus in the first hour, calling it the "Power Hour":

"The first hour of the crowdsale will be a Power Hour. During the Power Hour, 1 Ether will buy 170 1SŦ. After that, the price will change to 150:1, and then decrease every week until it reaches 100:1 in the fourth week." (https://web.archive.org/web/20170417105104/https://firstblood.io/sale/#).

|

Date |

Bonus |

|

Power Hour |

70% |

|

26 Sept–2 Oct 2017 |

50% |

|

3–9 Oct 2017 |

33% |

|

10–16 Oct 2017 |

17% |

|

17–23 Oct 2017 |

No bonus |

Table 7: The FirstBlood token bonus plan

Humaniq describes itself as a revolutionary blockchain-based financial services platform providing banking 4.0 services for the unbanked, utilizing mobile devices, and biometric identification systems. It provided a more granular approach to its ICO, with 50% bonus in the first two days, half of that in the following six days, and then half yet again in the next six days. It was somewhat mimicking the bitcoin reward system:

|

Date |

Bonus |

|

6–7 Apr 2017 |

49.9% |

|

26 Sept–2 Oct 2017 |

25% |

|

15–21 Apr 2017 |

12.5% |

|

22–26 Apr 2017 |

No bonus |

Table 8: The Humaniq token bonus plan

TenX provided 20% in the first 24 hours, 10% on days two and three, 5% from days four to seven, 2.5% from days eight to 14, and no bonus in the final 14 days. What TenX also did was offer two extra "goodies." Investors of more than 25 ether would receive a highly exclusive limited edition TenX debit card. For over 1,250 ether purchased, a founders' edition TenX platinum card would be gifted.

|

Date |

Bonus |

|

First 24 hours |

20% |

|

Day two and day three |

10% |

|

Day four to day seven |

5% |

|

Day eight to day 15 |

2.5% |

|

Final 14 days |

No bonus |

Table 9: The TenX token bonus plan

TenX provided an exceptionally detailed summary analysis post ICO, which actually revealed that the bonus structure didn't mean much because the ICO was over in seven minutes (https://blog.tenx.tech/reflecting-on-a-highly-successful-tenx-tokensale-b2705d593f1a). TenX did its presale 10 days before the actual sale and this was open to anyone willing to contribute at least 125 ETH, which was the equivalent of $40,000 USD at the time. TenX then showed the contribution address 15 minutes before the actual ICO.

Although TenX aimed for 200,000 ETH, due to price fluctuations after the conversion, it ended up with 245,000 ETH, as explained in blog.tenx.tech:

"Adding these 3 factors together increases the total ETH of slightly over the targeted 200,000 ETH to a total of 245,000 ETH. This amount may fluctuate quite heavily up or down, since roughly one third was contributed in non-ETH currencies (ERC20, BTC, LTC, DASH)." (https://blog.tenx.tech/reflecting-on-a-highly-successful-tenx-tokensale-b2705d593f1a).

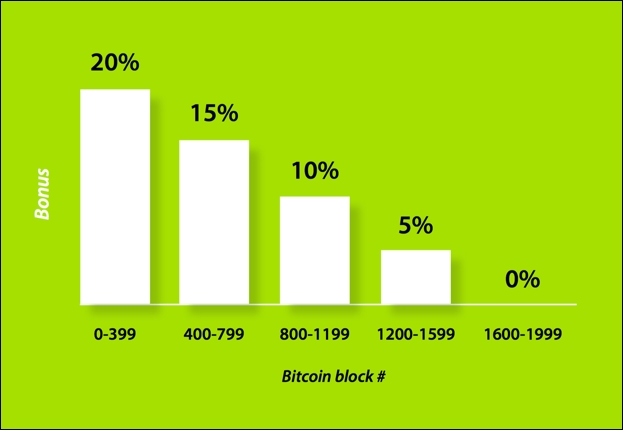

Tezos decided to provide a bonus structure not based on time, but based on the block number on the bitcoin blockchain. There was a 20% bonus from block 0-399 and then 15%, 10%, and 5% for each subsequent 400 blocks. What this really did was introduce an extra step for everyone because since the duration of each block was about 10 minutes, the 20% bonus would last for 400 blocks multiplied by 10 minutes, giving 4,000 minutes or about 2.78 days. If Tezos was trying to test some of its users' technical knowledge, it certainly achieved that.

Figure 6: The Tezos token bonus plan

Other ICOs started getting fancy by introducing different bonus layers. Synereo, a blockchain-based platform allowing direct monetization of content for content creators, had a million AMP (AMP being the token ticker symbol) bonus pool that would be proportionally distributed to all the contributors in the first 24-hour period, as explained at blog.synereo.com:

"For example: if Alice buys 10,000 AMPs, and the total number sold during the first day was 10,000,000 AMPs, Alice will receive an additional 10,000/10,000,000 * 1,000,000 = 1,000 AMPs."

Synereo also offered the standard sliding scale, where the earlier the contribution, the higher the bonus.

|

Date |

Bonus |

|---|---|

|

19 Sep–2 Oct 2017 |

~21% |

|

3–9 Oct 2017 |

~10% |

|

10–18 Oct 2017 |

No bonus |

Table 10: The Synereo token early bird bonus plan (https://blog.synereo.com/2016/08/29/synereos-second-fundraising-campaign-coming/)

Synereo also had a further bonus based on the amount contributed denominated in bitcoins. Therefore, to obtain the maximum bonus possible, an investor would contribute 200 bitcoins within 24 hours of the ICO starting on September 19, 2017.

|

Amount invested |

Bonus |

|

2 BTC |

3.33% |

|

10 BTC |

6% |

|

20 BTC |

9% |

|

50 BTC |

11% |

|

100 BTC |

13% |

|

200 BTC |

15% |

Table 11: The Synereo token bonus plan based on amount purchased

So, what can we learn from all of this? Firstly, the bonus structures are all different. Not having a bonus structure like Civic does remove potential speculators but with no incentive mechanisms, there is a risk that there will not be enough interest. One has to be very confident to pull this off. Also, having a simple bonus structure is important. Too many dates make it confusing, as well as using block numbers instead of dates.

An incentive scheme is also designed to induce the priming effect, where having a non-empty tipping jar can start the ball rolling and give the impression that if others are doing it, I might as well do it too, similar to the follower effect. It is also designed to combat everyone waiting until the last minute because this is in fact the optimal strategy and also to create FOMO. Waiting until the last minute gives the buyer the most amount of information to make a decision, while still receiving the same amount as if there was no incentive scheme.

NEM, a blockchain platform providing the capability of creating smart assets, did a fundraiser where bitcointalk users would reserve their spot by typing I'm interested or something to that effect. After 20 pages, a small fee of 0.001 BTC or 10 NXT was charged, approximately doubling every 10 pages.

|

Pages |

Fee |

|

First 20 pages |

Free to join |

|

Pages 21-30 |

0.001 BTC or 10 NXT |

|

Pages 31-40 |

0.002 BTC or 20 NXT |

|

Pages 41-50 |

0.004 BTC or 40 NXT |

|

Pages 51-60 |

0.008 BTC or 80 NXT |

|

Pages 61-70 |

0.016 BTC or 160 NXT |

|

Pages 71-80 |

0.0025 BTC or 250 NXT |

|

Pages 80+ |

0.03 BTC or 300 NXT |

Table 12: NEM's bonus structure was a reverse fee structure. The earlier one registered interest, the lower the entry fee.

NEM's initial concept was to distribute the tokens to around 3,000 to 4,000 supporters:

"Our current formula is number of NEM per stake spot = 4 billion/(total account stake + development stake). At the moment we are aiming for roughly 3-4000 accounts in which 5% is development stake, but it could be more, could be less depending on the fundraising." (https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=422129.0).

Bonuses could be considered as a presale providing greater rewards for the early adopters but this was then taken to the next level where sometimes a presale would happen a month or two before the actual ICO. In some cases, it even took place just days ahead of the ICO. When word got out that ICOs were a way to make some quick money, pre-ICOs or presales were a way to get a head start on everyone else.

Pre-ICOs sometimes came with a minimum purchase amount and the fundraising targets were often lower compared to that of the main ICO and tokens were usually sold cheaper. With private presales, they generally came with higher minimum purchase amounts than presales and they also took place much earlier. Typically, a separate smart contract was also employed to avoid mixing pre-ICO funds with the main ICO, to keep things simpler for auditing and reconciliation purposes. There was no hard or fast rule though.

OmiseGo is an open payment platform and decentralized exchange based on the Ethereum platform. It had a presale requirement of a minimum contribution of $5,000 USD crypto equivalent and a maximum contribution of $100,000 USD crypto equivalent.

Simple Tokens, a platform enabling companies to create, launch, and manage their own branded digital token economy on an open and highly scalable sidechain anchored to the Ethereum blockchain, had a "private presale" with a minimum investment of $200,000 USD (https://medium.com/ostdotcom/early-access-registration-for-simple-token-sale-is-now-underway-24a84125baf3). This was effectively a private round because it then had an "Early Access" sale, which could be considered the presale and then the general or public sale.

Another ICO that made a lot of noise was Telegram, a cloud-based instant messaging platform. Looking to raise over a billion USD, Telegram has reportedly secured $850 million USD in a "presale" from 81 accredited investors, including companies from Silicon Valley, such as Sequoia Capital and Benchmark (https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1729650/000095017218000030/xslFormDX01/primary_doc.xml). As if that was not enough, there is another Form D disclosure citing an additional $850 million USD raised from 94 investors, bringing the total to $1.7 billion USD (https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1729650/000095017218000060/xslFormDX01/primary_doc.xml).

Telegram was intending to have a public sale but since it raised too much in the presales, it did not go through with the public sale. If this is the power of having a platform of 200 million monthly active users, imagine what Facebook could do!

One of the side effects of a pre-ICO is that early investors or adopters tend to sell or "dump" the tokens as soon as they become tradable on exchanges. So, because they got the token for less than the price of the main ICO, there is almost a guarantee of short-term profits. This is more evident in ICOs that offer a steep discount, so this amount needs to be carefully selected.

Vesting is a term used to mean where employees or founders of a company earn shares over time, rather than all at once. This means that instead of having immediate equity in a company, a percentage of the shares are made available or "vest" over time. Vesting protects a company from employees or founders receiving all their shares at once and then walking away from the company or project.

This can be directly translated into the ICO world, where tokens that are made available to the founders can be quite substantial. 10% of 100 million tokens represents 10 million tokens. Shared between a handful of founders, that's a cool couple of million each. Vesting can also apply to tokens granted as bonuses for ICOs.

There was no standard vesting period for ICOs, though. Filecoin had a comprehensive vesting plan where investors or supporters had a default vesting period of six months minimum if tokens were purchased in the public sale or a 12-month minimum if purchased as part of the presale. Protocol Labs and the Foundation have a six-year linear vesting period. So, because the network has yet to be created, the vesting period will commence upon network launch and not when a token is purchased. The network is estimated to be launched in the second half of 2018.

A vesting period of 24 months, with six-month cliffs, became very popular. This meant that if a founder received 1,000,000 tokens, 250,000 tokens would be released every six months. ICONOMI, Airclipse, and Synereo had a 30-month vesting period for their founders. Brave had a 180 day "lockup" period. Bancor founders were subjected to a three-year vesting schedule. TenX founders and employees had a four-year vesting period.

|

Company |

Vesting period |

|

Brave[17] |

180-day lockup |

|

OmiseGo[18] |

12 months |

|

Airclipse[19], ICONOMI[20], Status[21] and Aragon[22] |

24 months with six-month cliffs for founders |

|

Synereo[23] |

30 months for founders |

|

TenX[24] |

Four years for founders and employees |

|

Bancor[25] |

Three years for founders |

|

Filecoin[26] |

Six-year linear for founders |

Table 13: Sample ICO vesting periods for various ICOs

Another aspect of the token mechanics was to decide on the soft cap and the hard cap. Some even had no cap at all! These caps are effectively fundraising goals.

An uncapped ICO is where there is no upper limit to the amount being raised. What the company is effectively saying is that no matter what the demand is, tokens will be created to cater for it. The Ethereum ICO was uncapped and sold approximately 60 million ETH.

What was interesting about the Ethereum ICO was that over the 62 days that it ran for, the price of bitcoin dropped from about $618 USD to $398 USD. This is a 36% drop in value. This meant that those who invested at the very last minute, ended up paying about the same rate of $0.33/ETH as those that invested early.

This highlights two important points. Firstly, the volatile nature of the cryptocurrencies being collected in an ICO can play havoc with the expected calculations and secondly, the duration of the ICO plays a part as well. The longer the duration, the more exposure to potential volatility, in both directions of course.

Ethereum is unique in that there is no finite limit on the total supply of ether, unlike bitcoin. Bitcoin has a maximum supply of 21 million bitcoins, of which about 17.19 million are currently in existence as of August 2018 (https://blockchain.info/charts/total-bitcoins). The current supply of ether is 101,106,416 as of August 2018 (https://etherscan.io/stat/supply). The number of ether created at its inception started at around 20% and drops in a non-linear fashion. This means that it drops approximately 4% in the first year, 3% the following year, 2% after that, and it keeps getting smaller for subsequent years (https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/150B9eytmjZ642tYD0jSdFZQHldmk7VG5Wm3KVctydpY/pubhtml).

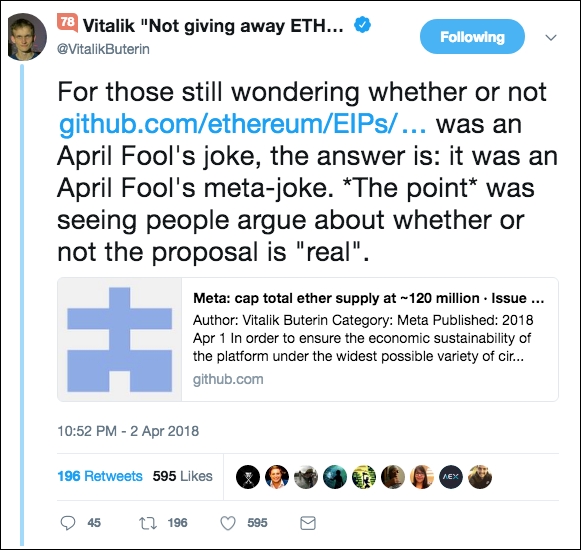

It was assumed that eventually the annual loss and destruction of ETH would balance the rate of issuance, so that a balance or equilibrium would be reached. Ethereum, however, likes to throw the proverbial spanner into the mix and is pondering a consensus model change from the energy intensive Proof of Work to Proof of Stake, which has been given the nickname "Casper." It also has this concept of a difficulty bomb dubbed "Ice Age", which slows down the block creation process at certain times. Add to this an April Fools' 2018 joke from Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin:

"In order to ensure the economic sustainability of the platform under the widest possible variety of circumstances, and in light of the fact that issuing new coins to proof of work miners is no longer an effective way of promoting an egalitarian coin distribution or any other significant policy goal, I propose that we agree on a hard cap for the total quantity of ETH. I recommend setting MAX_SUPPLY = 120,204,432, or exactly 2x the amount of ETH sold in the original ether sale." (https://github.com/ethereum/EIPs/issues/960).

Buterin then clarified in a tweet that it was a meta-joke, but some in the community took this seriously.

Figure 7: Buterin clarifying in a tweet that his proposal to limit the supply of ether was a meta-joke (https://twitter.com/VitalikButerin/status/980744740277661696)

Tezos took a leaf out of Ethereum's book and also had an uncapped ICO. Note that Tezos is an Ethereum competitor! The Tezos white paper gave an explanation:

"Following the example set by the Ethereum Foundation, there is no cap on the amount of contributions that will be accepted by the Foundation. This is done in order to ensure that participation is not limited only to insiders or the "fast fingered". The Tezos development team believes that an uncapped fundraiser will promote a widespread distribution of the tokens, a necessary prerequisite to launching a robust network." (https://www.tezos.com/static/papers/Tezos_Overview.pdf).

However, a counterargument could be made that Tezos did not have a specific goal in mind. There was no budget, no forecast, and no plan. Aware of this, Tezos did include a financial forecast with the heading if the foundation is endowed with… and provided scenarios of $6 million USD, $12 million USD, or $20 million USD. Above $20 million USD, it planned to offer student grants for conducting projects related to the Tezos ecosystem, and even more creatively to negotiate with a small nation-state the recognition of Tezos as one of their official state currencies, which would immediately give Tezos favorable treatment in terms of financial regulation (https://www.tezos.com/static/papers/Tezos_Overview.pdf). Attempt negotiation to purchase or lease sovereign land. (https://www.tezos.com/static/papers/Tezos_Overview.pdf).

Needless to say, with $233 million USD raised, this was significantly over the $20 million USD project, so it sounds like Tezos will be purchasing land if it ever gets through the legal issues and can access its funds!

Being uncapped also meant that the potential number of Tezos tokens in circulation is limited only by investors' willingness to participate. Scarcity is not an issue here but abundance is, along with the risk of overflooding the market with tokens when they hit exchanges, which they will.

While some entrepreneurs love the idea of having a war chest of funds and their names all over the media for being the next "largest" ICO, it can also show a lack of discipline. How many companies really need $100 million USD at the outset? With this negative perception of uncapped ICOs, capped ICOs became the de facto standard.

A capped ICO usually has two components: a soft cap and a hard cap. The decision to have a cap and have it met provides the market with confidence in the project and the team and shows that the company is not raising funds just for the sake of it.

A soft cap is the minimum needed for a project to proceed. This is typically determined by a project's budget and a forecast of the required funds to bring the product or service to market. The term "soft cap" is actually quite misleading because it is not actually a cap as such. A more accurate term would be a "minimum threshold" or a "minimum goal." If it isn't reached, then the project will shut down and return all the raised capital to the investors. Not all ICOs do this and some proceed with the project regardless of the capital raised. Some projects enter what some call "life support mode", where a decision is made on whether to continue, pause, or dismantle the project.

Veredictum was one such unfortunate ICO that had a soft cap of $2.5 million USD or 7,752 ETH, which it did not reach in September 2017. It then issued a blog post on how investors could reclaim their ETH.

Figure 8: Veredictum missed its soft cap and refunded ETH back to its investors

A hard cap is the absolute maximum an ICO will take. If reached, the ICO finishes and excess funds are returned to investors. Positive aspects about having an upper limit are that there is not an excess of investors and it creates scarcity. The investors that missed out will be eager to buy the tokens when they are made available on an exchange, for instance, and a hard cap that is reached often leads to a price increase when it is listed on exchanges. If all the investors were catered for then there is a potential for excessive selling or a "dump" when a token is listed, as investors attempt to realize short-term profits.

There is no exact science when picking a hard cap compared to a soft cap, but it does depend on the project needs. There are some general rules, though. Firstly, specify the hard cap before the launch. This figure must remain fixed to protect the token's integrity. This means that more tokens should not be created, even if it is programmatically possible to do so. Secondly, don't set a hard cap too low or else your project could be strapped for funds in the future. Thirdly, it is important to justify the amount of funds required, typically in the white paper.

The core issue with hard caps is that they tend to create an undesirable stakeholder distribution if they are reached too fast. For open-source or open-community projects, the founders will benefit from a wider distribution of ownership, with a lower average stake. Wider community-owned tokens create stronger network effects, which grow faster and are highly desirable for projects. Unfortunately, a hard cap or maximum limit naturally prevents these desirable distributions. Hard caps on popular projects create a first come, first served competition, where "whales" or large investors gobble up the majority of the supply and lock out the smaller players.

Most ICOs did not initially require identity verification or even have limits on the transaction size itself, allowing large investors to do as they pleased. In fact, those ICOs without KYC found that they could not convert their cryptocurrencies raised to fiat currency because of banking regulations. To combat the problem of not having a limit on the transaction size, maximum contribution limits were placed for each transaction. Whales then had to buy in lots of small tuna chunks! While this may be a pain, it can be easily circumvented by automating the purchase process.

Another option was to place a maximum contribution limit per transaction, plus a maximum contribution per block. For example, on the Ethereum network each block takes around 20 seconds to confirm. One could place an artificial maximum of $20,000 for every 180 blocks. 180 blocks represent one hour and therefore the contribution limit becomes $20,000 per hour. This is like a time delay for the whales, but it is still not a particularly strong deterrent.

A proportional structured ICO is an option, such as the one performed by Augur. Augur created 11 million tokens, of which 80% or 8.8 million tokens were distributed in what it saw as a fair and equitable manner. Augur called it a live action model, where the bigger the contribution, the more tokens were received proportional to everyone else. An example would be to imagine a pie with 8.8 million slices (http://augur.strikingly.com/blog/the-augur-crowdsale). That is either a really big pie or it has lots of very thin slices! If the first contributor, say Alice, paid $1 or the crypto equivalent, she would own all 8.8 million pieces. If the second person, say Bob, contributed $2, he would get twice as much as Alice. In this case, it would be 2.93 million for Alice and 5.87 million for Bob. It is basically a primary school fractions calculation.

To take the Augur model one step further, a proportional refund scheme is yet another option. Here, a maximum cap is designated where everyone contributes as much as they want. At the end, a refund is provided in proportion to how much the cap was exceeded by. For example, if the cap is $10 million USD and $20 million USD is received, then everyone gets half their contributions back. If $50 million USD was received by five people at $10 million USD, $15 million USD, $12 million USD, $8 million USD, and $5 million USD, it means that five times as much was received. Therefore 1/5th of everyone's contribution will be accepted and 4/5ths will be refunded.

OmiseGo experienced an enormous demand for its token and ended up increasing its overall hard cap from $19 million USD to $25 million USD, with its presales cap at $21 million and $4 million sold using other pre-funding platforms (https://www.omise.co/omisego-crowdfunding-structure-update).

Aragon provided a presales transparency report where, interestingly, it didn't specify a minimum purchase but a maximum one. Institutional buyers were allowed to contribute the equivalent of $40,000 USD in ether, while personal buyers could contribute up to $10,000 USD in ether. For liquidity purposes, ShapeShift was also allowed to purchase an additional $20,000 USD in ether.

Aragon received contributions from six buyers during its presale, totaling 2,719 ETH, the equivalent of $170,000 USD. The buyers were CoinFund, ICONOMI, ShapeShift, Joe Urgo, Daniele Levi, and an anonymous Ethereum founding member.

The presales conditions were at a 20% discount and had a six-month vesting schedule, with a three-month cliff.

|

ETH |

USD | |

|

Development |

1,993 ETH |

$179,000 USD |

|

Security audits |

50 ETH |

$4,500 USD |

|

Legal |

208 ETH |

$18,700 USD |

|

PR |

107 ETH |

$9,600 USD |

|

Advertisements |

134 ETH |

$12,000 USD |

|

ENS |

202 ETH |

$18,200 USD |

|

Other |

15 ETH |

$1,350 USD |

|

Total |

2,719 ETH |

$244,350 USD |

Table 14: Aragon's presale allocation (https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=1902482.msg19070685#msg19070685)

Aragon then employed the concept of a hidden cap in its ICO. The argument here was that an uncapped ICO would allow as many community supporters to invest as possible, but a security cap was required as a safety measure to avoid the ICO getting out of control. Therefore, a hidden cap was created, which was effectively a soft cap.

In conjunction with this, there was also a maximum hidden hard cap that was baked into the contract as a fallback mechanism. This essentially put an explicit limit on the amount raised, regardless of what happened to the hidden cap. This hidden hard cap was subsequently revealed to be 275,000 ETH, which was roughly $25 million USD.

The hidden cap was only known to the Aragon founders, Luis Cuende and Jorge Izquierdo, and was designed to incentivize small buyers. The logic here was that the whales needed to know the cap in order to be able to determine how many tokens were required to control a sizeable amount of the market. By hiding this important piece of information, a more even token distribution could be achieved.

When the ICO was about to start, the team realized that with large transaction volumes queuing up on the Ethereum network, sending a transaction signal to reveal the hidden cap was required at the start of the ICO (https://www.reddit.com/r/ethtrader/comments/6bqnhf/aragon_ico_cap_released_275k_eth_21m/?sort=old). If they sent the signal later, the signal transaction would have been stuck in the processing queue, causing potential havoc.

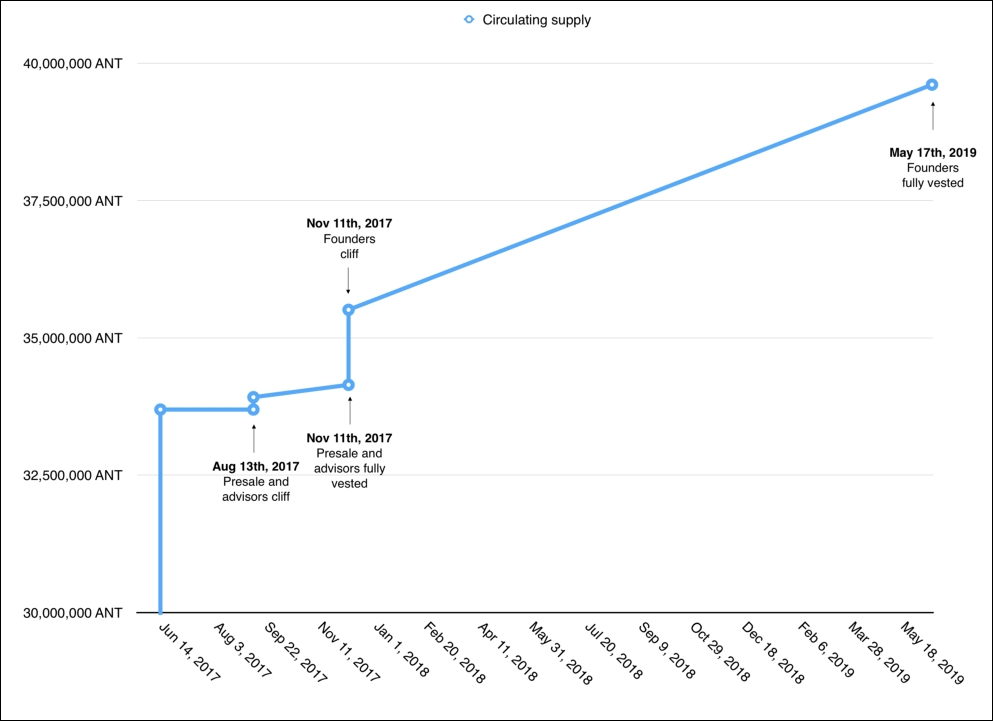

Aragon produced a useful circulating supply chart that showed the various vesting periods and how they would affect the supply. The initial circulating supply was 33 million ANT, with a one-month cliff for advisors and those who participated in the presale. About five months after the ICO, on November 11, 2017, advisors' and presale tokens would fully vest. This date would also represent the first cliff for founders. Founder tokens would fully vest 18 months later.

Figure 9: The Aragon circulating supply with vesting indicators (https://blog.aragon.one/the-aragon-token-sale-the-numbers-12d03c8b97d3)

The Aragon ICO ended with 2,916 transactions and 2,403 unique buyers, which Aragon believed achieved an even token distribution. While two and a half thousand contributors was a commendable amount, this paled in comparison to the likes of Status or Kyber Networks, that achieved over 20,000 contributors. Having said this, they both raised substantially more: $90 million and $48 million respectively.

Status used the idea of a dynamic ceiling in its ICO in an effort to prevent large contributors dominating and favoring smaller contributors. A dynamic ceiling was a concept where only a maximum amount of funds would be accepted over a particular time interval. It was analogous to a series of miniature hidden hard caps.

Status set the first hard cap at 30,000 ETH, which was approximately 12M CHF (Swiss Franc) at the time (~$12 million USD). This was intentionally large and made known to incentivize large contributors. This meant that Status could make one large transaction and incur less transaction fees. Subsequent hard caps were lower, meaning that large purchases were be rejected and investors had to break them down into smaller purchases for the transactions to be accepted.

A maximum upper limit of 300,000 ETH was set as the hard ceiling or maximum contribution amount.

The Status ICO was an obvious success, raising $90 million, but the verdict is still out on the dynamic ceiling model. By Status' own admission, it doesn't see this model working in the future and to date, it hasn't been replicated elsewhere, at least not to the extent seen with Status.

Gnosis did a very smart token sale. It did its homework and in December 2016, Chief Strategist Matt Liston released a blog titled Introducing the Gnosis Token Launch. This is where the concept of the Dutch auction was introduced. Keep in mind that this was five months before the actual ICO.

A Dutch auction is where a good (or service) is set at an artificially high price where demand is known or believed to be zero. At publicly known time intervals, the price ticks down in publicly known price values. The price continues to tick down until the first bid is received. At this point, the auction ends immediately and the bidder wins the goods at that price point. The advantage is that the buyer recognizes their fullest economic benefit from the sale because that is what they were willing to pay in the first place. It is also quick and simple to implement and understand and only one bid is required. There are not a million hands waving all over the place, for instance, like the floor of the New York Stock Exchange in the good old days! Gnosis took this concept and modified it slightly.

In February 2017, Martin Koppelmann, the CEO and co-founder of Gnosis, released a blog post titled Why so complicated? (https://blog.gnosis.pm/why-so-complicated-ddff533c5620). In this clever blog, he compared the impending Gnosis ICO to other past ICOs, based on several criteria.

First there was an argument made against raising funds with a fixed token supply, as in the case of Augur. Gnosis pointed out that when buyers made a purchase, the number of tokens they received in return could only decrease. This was true because after a bonus round, for example, the tokens on offer reduced. In the Gnosis-modified Dutch auction, the number of tokens a buyer received could only go up. This was because Gnosis started the auction at a ridiculously high price. Buyers then made purchases based on their own price point, until the criteria of either $12.5 million had been raised or nine million GNO tokens sold.

The last price that the GNO tokens were purchased for when the preceding criteria was met was the final price that everyone paid. For example, if the starting price was $30 and two people decided to contribute $100 each, the auction would still continue because the criteria would not yet have been met.

The next day it would drop to $29 and five people would contribute $500 each and this would continue until $12.5 million was reached. If the last bid just before $12.5 million was $18, for example, then this would be the price that everyone would be paying. This would mean that the two people who thought $30 was a good price would actually receive more than they anticipated because of the $18 price point. That is why Gnosis claimed that the amount the buyer received could only increase.

Gnosis also compared this to doing an ICO with an unlimited token supply, such as the case with Ethereum. Here, the buyer will not know the true value of the number of tokens held because the supply continuously increases.

In a fixed price scenario, like Civic and many others, Gnosis argued that the seller has to set the right price up front. For example, Civic decided on 33 million tokens at $0.10 USD each. Here Gnosis argued that its ICO structure allowed the market to find the best price. Gnosis was also not a fan of an early buyer bonus so didn't implement this.

This sounded great on paper, but what actually eventuated was something completely different. Gnosis sold out in 10 minutes! Due to the ICO hype and FOMO, as soon as Gnosis set that artificially high price where demand is known or believed to be zero of $30 USD, everyone bought what they could. This meant that the $12.5 million maximum cap was triggered and the ICO closed. At the $30 price point, only 4.17% of the allocated nine million tokens were sold (https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1vYjDat8wLd97pEfrdkzOcHd5ZLOlYjpDSkJaTnEDe1E/edit#gid=0). The percentage of tokens sold was supposed to increase at the same rate that the price was to decrease but because the price didn't have a chance to decrease, the smallest proportion of tokens to be released was released.

This led to outrage because it seemed like out of the 10 million tokens, 90% was going to be available to the public when in reality, only 4.17% was. This gave Gnosis a valuation of $300 million (100%/4.17% x $12.5 million). There was a lot of backlash but the conclusion to this is that the market can be totally irrational. Gnosis decided to freeze the remaining 85.83% for one year. One year is not a long time so it will be interesting to see what happens to the value of the tokens that are unfrozen.

The point here is to take into consideration the hype, and the fact that markets are irrational, if a Dutch auction of this sort is contemplated. There are also improved variations of this Dutch auction that others have proposed, albeit very conveniently after the fact.

The following table can be used as a guideline for ideas when looking at different factors in structuring the mechanics of an ICO:

|

Options |

Examples/comments | |

|

Supply |

|

|

|

Price |

|

|

|

Distribution |

|

|

|

Cap |

|

|

|

Duration |

|

|

|

Presales/bonuses |

|

|

|

Pre-ICO and private sales |

|

|

|

Vesting period |

|

|

Table 15: A summary of ICO considerations

The methods of how tokens were created and sold in ICOs during 2016 and 2017 were varied, experimental, and creative. There were very few standards or patterns initially, as each ICO team experimented with the number of tokens to create, how many to distribute to their community of supporters and how many to withhold for various other purposes.

In this chapter, we learned that presale bonuses were usually a given but with insatiable demand, pre-ICOs were created, which then escalated to private sales. The rush was on to get in as early as possible, in order to essentially be able to flip or sell the tokens as soon as they hit the exchanges for a quick profit.

We learned that uncapped ICOs were frowned upon by the community, hard caps became the norm and soft caps should really be called a minimum threshold or goal. With the frantic rush in 2017 and big whales gobbling up tokens like plankton in the South China Sea, inventive ways were formed to try to decentralize token holders.

Now that we have a grasp on the mechanics of the token, let's turn our focus to the three most important aspects before the token sales can begin: the white paper, the website, and the team.

- https://augur.stackexchange.com/questions/113/how-were-augur-ico-funds-and-rep-tokens-distributed?utm_medium=organic&utm_source=google_rich_qa&utm_campaign=google_rich_qa

- https://help.lisk.io/faq/ico/how-were-the-initial-lsk-tokens-distributed

- https://blog.wavesplatform.com/waves-ico-structure-and-timeline-87db476cc586

- https://iconomi.zendesk.com/hc/en-us/articles/115002851065-ICN-token

- https://blog.synereo.com/2015/03/18/crowdsale-announcement-2/

- http://www.theicotrain.com/docs/GNTterms.pdf

- https://www.reuters.com/article/us-blockchain-funding-gnosis/blockchain-startup-gnosis-to-freeze-tokens-after-strong-sale-idUSKBN17R2RD

- https://gamecredits.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/MobileGo-Whitepaper.pdf

- https://basicattentiontoken.org/bat-sale-overview-and-how-to-participate/

- https://medium.com/@bancor/bancor-network-token-bnt-contribution-token-creation-terms-48cc85a63812

- https://blog.status.im/status-contribution-period-recap-36e64d35d3e4

- https://tokensale.civic.com/

- https://pillarproject.io/tokens/

- https://coinlist.co/assets/index/filecoin_index/Filecoin-Sale-Economics-e3f703f8cd5f644aecd7ae3860ce932064ce014dd60de115d67ff1e9047ffa8e.pdf

- https://kinecosystem.org/static/files/Kin_Whitepaper_V1_English.pdf

- https://blog.kyber.network/kybernetworks-token-sale-terms-overview-de031ce9738e

- https://basicattentiontoken.org/faq/#distribution

- https://cdn.omise.co/omg/crowdsaleterms.pdf

- https://medium.com/@Airclipse/founders-vesting-period-b47804d0fca4

- https://iconomi.zendesk.com/hc/en-us/articles/115002851065-ICN-token

- https://status.im/whitepaper.pdf

- https://blog.aragon.one/the-aragon-token-sale-the-numbers-12d03c8b97d3

- https://blog.synereo.com/2015/03/18/crowdsale-announcement-2/

- https://www.tenx.tech/whitepaper/tenx_whitepaper_final.pdf

- https://medium.com/@bancor/bancor-network-token-bnt-contribution-token-creation-terms-48cc85a63812

- https://coinlist.co/assets/index/filecoin_index/Filecoin-Sale-Economics-e3f703f8cd5f644aecd7ae3860ce932064ce014dd60de115d67ff1e9047ffa8e.pdf