4

THE VOCABULARY OF COLOR

Hue / The Artists' Spectrum / Primary, Secondary, and Intermediate Colors / Saturated Color / Other Spectrums, Other Primaries / Chromatic Scales / Complementary Colors / Cool and Warm Colors / Analogous Colors / Tertiary Colors: Chromatic Neutrals / Black, White, and Gray / Value / Pure Hues and Value / Tints and Shades / Monochromatic Value Scales / Comparing Value in Different Hues / Line / Value and Image / Transposing Image / Saturation / Saturation: Diluting Hues with Gray / Saturation: Diluting Hues with the Complement / Theoretical Gray / Tone

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in a rather scornful tone,

“it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”—Lewis Carroll

The words for colors in everyday life—“red,” “green,” “blue,” and so on—do not have precise meanings. Instead, each word is a code for a range of similar sensations. The same is true for words that describe colors, like “vivid,” “dull,” “dark,” or “light.” “Red” is red and never blue, and “vivid” is never dull, but at the same time each word encompasses a wide range of visual experiences.

When a word is used to identify a color sample, or to describe a color not seen, it means something slightly different to each person. Mary and John see the same sweater. Mary calls it red; John insists it is red-orange. Not everyone senses colors in exactly the same way, and even if they did, individuals do not think of colors in exactly the same way. The result is a stalemate, a difference of opinion, an inability to agree on exactly what a particular sample is—and real difficulty in communicating ideas about it. It makes no difference whether a color is seen as pure light, as a solid object, or as a printed page. Each person interprets and names particular colors in his or her own way.

The design process calls for a vocabulary that can communicate color ideas with more precision, but no new words are needed for this. If a color cannot be precisely identified by words, it can nevertheless be described. Colors have attributes that can be observed and named. Whether these are called qualities, aspects, dimensions, or something else, they all refer to the same thing—attributes that are present in colors of all kinds: colors of light, or ink, or yarn; colors that are glossy or matte, transparent or opaque, chalky or clear. An observer with a trained eye and the right words can describe a color relative to another and communicate differences between them with reasonable precision.

The vocabulary of color also includes words to describe relationships between colors. Used together, the terms of description and relationship make it possible to convey ideas about color using words whose meanings are consistent and objective. The words for three descriptive qualities of colors are already familiar:

- Hue: the name of the color—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet

- Value: the relative lightness or darkness of a color, and

- Saturation or chroma, the hue-intensity or brilliance of a sample, its dullness or vividness

Each word communicates an independent idea, but the ideas are independent only for the purposes of study. Each is present in every color, and all are needed to describe it. A sample may have additional characteristics, like opacity or translucency, but its color can always be described first in terms of its hue, value, and saturation.

Hue

Hue means the name of the color. In science, the colors of light, or spectral colors, can be established precisely by a measurement of wavelength, and the words “hue” and “color” are used to mean the same thing. In everyday speech (including in this book) the word “color” is used in two different ways. It can mean (more precisely) the hue of something or (more generally) the complete experience of its hue, value, and saturation together. Only the context in which it is used tells which meaning is intended.

“Hue,” however, always means only the name of the color. Chroma is a synonym for hue. It is part of some familiar color words:

- Chromatic: Having hue

- Achromatic: Without hue

- Polychromatic: Having many hues

- Monochromatic: Having one hue only

The average person can distinguish about 150 spectral colors (colors of light), and each one can be described using one or two of only six words.1 The only names ever needed to describe hue are:

RED ORANGE YELLOW GREEN BLUE VIOLET

A color is called by the name of its most obvious, or dominant, hue. Every color name represents a family of related hues.2 Nearly all color samples include more than one hue, but one hue is most apparent and others are present in smaller proportion. A sample of color paper may seem to be perfectly yellow until it is placed next to a different yellow. Suddenly, one seems to tilt toward yellow-green; the other, toward yellow-orange. Both are called yellow because yellow predominates in each. Using the word “contains” helps to evaluate colors. “This yellow contains some orange” is perfectly descriptive. It identifies the principal hue and another that modifies it.

Figure 4–1. Color Names. Color names are not absolute. Each belongs to a family of related hues.

The Artists' Spectrum

The artists' spectrum is a circle that illustrates the visible hues in their natural (spectral) order. The spectrum of visible light is linear, moving from short wavelengths of light (violet) to long ones (red), and the order of its colors is fixed. The artists' spectrum is also fixed in its order of colors, but it has six hues instead of seven and they are presented as a continuous circle, with violet forming a bridge between red and blue. The artists' spectrum is also called the color circle or color wheel.3

There are too many hues in the range of human vision to illustrate all of them in one circle, so the artists' spectrum is a sort of visual synopsis. The basic spectrum is made up of six hues: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet. An expanded spectrum has twelve hues, adding yellow-orange, red-orange, red-violet, blue-violet, blue-green, and yellow-green, but no new color names are introduced.

Figure 4–2. The Artists' Spectrum.

The artists' spectrum is usually limited to six or twelve hues only because this is a concise, easily illustrated figure. It can be expanded to any number of hues as long as the added colors are inserted at regular intervals in all hue ranges. There can be six, twelve, twenty-four, or more hues (but not thirty-seven or fifty-one). The only limits to the number of places on a color circle are the limits of human visual acuity and the practical problems of illustrating it.

The artists' spectrum can be illustrated in any medium. If the medium is light on a screen, the colors will be sharp and clear, even measurable as spectral hues. A subtractive medium like gouache or acrylic paint illustrates colors in a less measurable way. The colors in a painted spectrum are choices made by the artist, but as long as the hues are reasonably true and in sequence, and the intervals between them well spaced, color circles can vary a good deal in appearance but be equally acceptable as representing the sequence of visible hues.

Primary, Secondary, and Intermediate Colors

Red, yellow, and blue are the primary colors of the artists' spectrum. They are the simplest hues. They cannot be broken down visually into other colors or reduced into component parts. The primary colors are the most different from each other because they have no elements in common. All colors on the artists' spectrum are mixed visually from the primaries red, yellow, and blue.

Green, orange, and violet are the secondary colors of the artists' spectrum. Each secondary color is an even interval, or visual midpoint, between two primary colors:

- Green is the middle mix of blue and yellow.

- Orange is the middle mix of red and yellow.

- Violet is the middle mix of blue and red.

The secondary colors are less contrasting in hue than the primary colors. Each secondary color contains a primary in common with one of the others. Orange and violet each contain red, orange and green each contain yellow, and green and violet each contain blue.

Yellow-orange, red-orange, red-violet, blue-violet, blue-green, and yellow-green are the intermediate colors. They are the midpoints between the primary and secondary hues. Like the secondary colors, each is made up of two primaries, but in different proportions. Many times these colors are referred to as tertiary colors, but this is inaccurate. Tertiary colors contain three primary colors, not two.4

Saturated Color

A saturated color is a hue in its strongest possible manifestation. The reddest red imaginable, or the bluest blue, are saturated colors. Saturated colors are also called pure colors or full colors. They are at maximum chroma. Saturated or pure colors are also defined by what they do not contain. A saturated hue is made up of a single primary color or two primaries in some mix or proportion, but never includes a third primary. A saturated hue does not contain black, white, or gray.

Saturated colors are not limited to the six or twelve named hues of the artists' spectrum. As long as a color contains only one or two primaries and is undiluted by black, white, or gray, it is a saturated color. Imagine the full range of visible hues as an enormous circle, each color blending into the next like a circular rainbow. Any hue at any point on that circle is a saturated color. The only limit to the number of saturated colors is the limit of human color vision.

Other Spectrums, Other Primaries

The artists' spectrum illustrates one color-order system. It is familiar, visually logical, easy to represent as a two-dimensional figure, and allows for theoretically unlimited expansion. Scientific and nonscientific disciplines use other names and other spectrums to illustrate alternative color-order systems. Choosing one spectrum instead of another is exactly that: a choice. No spectrum is necessarily more correct than another. The circles may vary in the names of colors, in the number of colors illustrated, and in the assignment of what might be called “prime points” on the wheel. Wilhelm Ostwald, for example, devised an eight-hue spectrum that includes “sea-green” (blue-green) and “leaf-green” (yellow-green). Psychologists propose a four-hue “opponent-process” spectrum of red, green, yellow, and blue; its basis lies in nineteenth century observations about color vision.

Figure 4–3. Alternative Spectrums. Wilhelm Ostwald's spectrum has an eight-hue basis.

The different color circles may at first appear to conflict, but all share the same color order. Colors may be added or omitted. There may be a slight shift in the placement of opposites. Albert Munsell, for example, places blue-green, not green, opposite red. But no spectrum places red next to green, or orange next to blue. Arguments made for the number of colors included and their names are intellectual exercises. All color circles include primary hues in some way, and all follow the same color order.

Chromatic Scales

A chromatic scale is a linear series of hues in spectrum order. A series of hues between blue and orange (blue-green-yellow-orange), for example, is a chromatic scale. A chromatic scale can illustrate pure (saturated) colors or more complex, diluted colors. Its defining characteristic is that each step in the progression is a change in hue.

Figure 4–4. Alternative Spectrums. The psychologist's spectrum has only four hues.

Complementary Colors

Complementary colors are hues that are opposite one another on the artists' spectrum. Together, the two are called complements, or a complementary pair. The basic complementary pairs of the artists' spectrum are:

Figure 4–5. Complementary Colors. Complements are opposite each other at any point on the artists' spectrum.

- Red and green

- Yellow and violet

- Blue and orange

In each of these pairs, one hue is a primary color and the other is a mixture of the other two primaries. The three basic complementary pairs are different from each other in exactly the same way as the primary colors: neither half contains a hue in common with its opposite.

The complementary relationship is not limited to the three basic pairs. Whether a spectrum is illustrated with six hues or extended to many more, a line drawn across the center of the circle from any point connects a pair of complementary colors. Every pair of complements includes the three primary colors in some mix or proportion, but only the three basic pairs have total contrast of hue. In all other pairs, each half includes a common primary. Blue-green and red-orange each contain yellow, yellow-green and red-violet each contain blue, and blue-violet and yellow-orange each contain red.

The complementary relationship is fundamental to color vision, to special effects and illusions, and to color harmony.5 Every color has an opposite that is its complement. The complementary relationship persists whether colors are pure hues or have been diluted in some way. No matter what the value or saturation of a color, it maintains at all times a complementary relationship with its opposite.

Cool and Warm Colors

Cool and warm are words used to describe two opposing qualities of hue. Cool colors contain blue or green: blues, greens, violets, and steps between them. Warm colors are reds, oranges, yellows, and steps between them. Warmth or coolness in hues is sometimes referred to as color temperature.6 The primary colors are weighted toward the warm. Only blue is cool, while both red and yellow are considered warm. As a result the entire spectrum is more heavily “warm” than it is “cool.” Blue is the polar extreme of cool, and orange, made of red and yellow, is the polar extreme of warm.

Warmth and coolness in colors are not absolute qualities. Any color, even a primary, can appear warmer or cooler relative to another color. There are cooler reds (closer to violet) and warmer ones (closer to orange). Violet is usually considered to be a cool color, but one violet can be characterized as warmer than another because it contains more red.

The terms “cool” and “warm” are helpful in describing families of colors or for comparing colors for warmth or coolness alone. They are less useful terms when hues need to be adjusted. Directing a color change toward a specific hue communicates more clearly: “This violet is too warm; add some blue. This red is too cold. Warm it up; bring it closer to orange.”

Analogous Colors

Analogous colors are hues that are adjacent on the artists' spectrum. Analogous color groupings contain two primaries but never the third. The traditional definition of analogous colors is “a group of colors consisting of a primary color, a secondary color, and any and all hues that lie between the two.” In this time-honored definition both a primary and a secondary are present and the primary color is dominant: every color in the group contains 50 percent or more of it. Typical combinations are blue, blue-violet, and violet (blue dominant); yellow, yellow-green, and green (yellow dominant); and red, red-orange, and orange (red dominant).

A more generous definition might state that analogous colors are “any group of colors that lie within the boundaries of a primary color and a secondary color.” This broader definition includes groups in which a primary or secondary color is not present. A range of three or four intervals of yellow-greens is analogous, but no primary yellow or secondary green is present. Red, red-red-violet, and red-violet are analogous, but the secondary violet is not present. As long as a group of colors lies between a primary and secondary color and does not extend beyond either, that color grouping is analogous.

Analogy is not confined to pure colors. Colors that have been diluted in any way can also be analogous. Analogy is a relationship between hues no matter what their value or saturation.

Analogy affords the designer an opportunity to add colors to a composition without disturbing an already established palette. A color scheme of red and orange is enriched, not changed, by the addition of red-orange.

Figure 4–6. Analogous Colors, Cool and Warm.

Tertiary Colors: Chromatic Neutrals

Another way to characterize complements is to say that they are a pair of colors that when mixed produce a chromatic neutral—a color of no identifiable hue. These mixtures are the tertiary colors. “Tertiary” means “of the third rank,” and this is an enormous, almost limitless, class of colors. Tertiary colors have been defined as “gray or brown, a mixture of two secondaries,” which, of course, can also be stated as “a mixture of three primaries.”7

A color that has been dulled by the addition of its complement is a muted hue, not a tertiary color. Red dulled by the addition of a little green is still red. Tertiary colors are chromatic neutrals. They cannot be identified as hues, but neither are they a mix of black and white.

In theory, when three primaries are mixed in a subtractive medium, the mixture will absorb all wavelengths of light and the result will be a “perfect” tertiary—a sample with no identifiable hue at all. In real life, the results are very different. Colorants do not reflect single, spectral hues. Each tube or jar contains substances that reflect more than one wavelength, although the underlying colors may not be apparent. When three primaries are mixed, each change in the proportions of the mix produces a color that is unique: neutral, nameless, and subtle. Tertiary colors are a sort of color soup, containing all possible ingredients but with none dominant (although a trained eye can often identify the ingredients).

The word “brown” is used to describe many of the colors in this family. Brown is not a hue. “Brown” is used instead of “tertiary color” because it is common usage and describes a family of familiar sensations. Browns typically have an orange or red undertone rather than a cool one, but browns can tilt in any direction—they can be more or less red, or orange, or yellow, or even more blue, green, or violet.

Figure 4–7. Mixing Complements. When complementary colors are equally mixed, the result is a sample of no discernible hue.

Black, White, and Gray

Black, white, and gray are achromatic. They are without hue. Absolute blacks and whites exist only in the medium of light. Light can be measurably white, a perfect balance of RGB, and the total absence of light can be completely black. Subtractive colorants for black and white are not perfect. They nearly always include some hidden hint of hue, and even the blackest blacks have some slight reflective power. When a black sample is placed next to a different black (or a white next to a different white, or a gray next to a different gray) even the slightest presence of hue in one or both becomes visible. Grays in subtractive media are often labeled as “warm” or “cool” in acknowledgment of their chromatic undertones.

Value

Value refers to relative light and dark in a sample. Hue is circular and continuous, but value is linear and progressive. A series of steps of value has a beginning and an end. Value contrast exists whether or not hue is present.

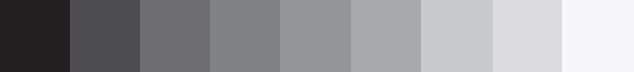

Value is first and most easily understood as a series of intervals between black and white. White is the highest possible value. Middle gray, the midpoint between black and white, is a middle value, neither dark nor light. Black is the lowest possible value. A value scale is a series of ever-doubling steps between poles of dark and light. Each step in a value series is a middle interval between the two on either side of it: half as dark as the one before it and twice as dark as the one following.8

Figure 4–8. Value Scale. A value scale moves from dark to light.

Pure Hues and Value

Value is associated with the idea of luminosity. A hue that is described as luminous reflects a great deal of light, appears light, and is high in value. A nonluminous hue absorbs light, is dark, and is low in value. Each of the six spectrum hues is at a different level of value. Yellow is lightest hue by far, and violet the darkest. Red, orange, green, and blue are darker than yellow and lighter than violet.

What is not immediately apparent—but important—is that the saturated colors of the artists' spectrum are not at evenly spaced steps of value. The value difference between yellow and green, for example, is much greater than the difference between blue and green. The artists' spectrum illustrates colors at evenly spaced intervals of hue, but not at evenly spaced intervals of value.

An argument is sometimes made for expanding the spectrum with more intervals in the yellow-to-blue and yellow-to-red ranges than in the blue-to-red range. The great difference in value between yellow and the other primary colors makes it possible to include many more perceptible steps of hue in colors that contain yellow than in those made of red and blue. A spectrum illustrated in this way would have many steps in the orange and green ranges, which would create an immediate problem in establishing complementary pairs. So many possible intervals can be illustrated between colors that contain yellow that they might actually end up opposite each other on a circle.

The purpose of the spectrum is to illustrate the full range of visible hues. No matter how many intervals are inserted between yellow-to-red and yellow-to-blue, no new hue is introduced. To say that there are “more hues” between yellow-to-red and yellow-to-blue than between red-to-blue misunderstands the meaning of “hue” and the nature and purpose of the spectrum.

Tints and Shades

Much of the time colors are not used at full saturation. Instead, they are diluted in one or more ways. The simplest way to dilute pure colors is to change their value by making them lighter or darker. A tint is a hue that has been made lighter. A shade is a hue has been made darker.

Tints are sometimes called hues with white added; shades are sometimes called hues with black added. “Added black” or “added white” is not necessarily meant as a recipe for paint mixing. “Added white” is just another way of saying “made lighter,” and “added black” another way of saying “made darker.”

Tinting makes colors more light-reflective. A great deal of white added to blue, for example, can make a tint so light-reflective that it is barely identifiable as blue. A fraction of white added to blue, on the other hand, yields a blue that is a more intense color experience than its saturated “parent.” Violet, the darkest of the pure hues, seems more chromatic when white is added. Strong tints are sometimes mistaken for saturated colors, but no matter how hue-intense and brilliant a tint may be, it is a diluted hue, not a saturated color.

Shades are reduced-hue experiences. Black absorbs all wavelengths of light, so adding black reduces light-reflectance. Even slightly shaded hues are rarely mistaken for saturated colors. The range of shades is less familiar than tints, but it is just as extensive.

Monochromatic Value Scales

A monochromatic value scale is a single hue illustrated as a full range of values in even intervals, including both tints and shades. Monochromatic value scales are slightly more difficult to illustrate than white-to-black scales. No one seems to have difficulty imagining (or illustrating) tints of pure colors. Lightening most colors, with the exception of yellow, seems to make them more hue-intense. Understanding and illustrating shades can be more difficult. Shades of cool colors, like dark blue or dark green, are reasonably easy to identify, but shades of warm colors can be problematic. Saturated yellow is so high in value that many people find it particularly difficult to associate yellows (and oranges) with their shades because the essential nature of yellow, alone or as a component of orange, is so luminous and opposite to dark. But like all colors, yellow and orange can be illustrated as a full range of values, from near-white to near-black.

Figure 4–9. Hue and Value. Any hue can be illustrated as a range of tints and shades.

Figure 4–10. Determining Relative Value. Isolating samples is helpful in making value comparisons. An opaque white paper with a small hole cut in it works well.

Figure 4–11. Hues of Equal Value. This spectrum illustrates hues of equal value. Which hues are saturated, which are tints, and which are shades?

Comparing Value in Different Hues

Deciding which of two gray samples is lighter or darker is not difficult. Deciding which of two samples of a single hue is lighter or darker is also straightforward. Determining which of two different hues is lighter or darker than the other is somewhat difficult. It is more difficult when one hue is warm and the other cool, and with the exception of red and green, very difficult when the hues are complementary.

Deciding when different hues are equal in value is most difficult of all. Only saturated red and green are equal in value. In order for other complementary pairs to be made equal in value, one must be made darker or lighter. Adding a great deal of black to yellow can make it as dark as violet. Adding a great deal of white to violet can make it as light as yellow.

Figure 4–12. Seven Steps of Equal Value in Six Hues. With a limited number of places, some saturated hues may not appear at all.

Line

A line is an elongated area of color. There are thick lines and thinner ones, broken lines and lines of varying width, but all lines share the same two attributes: great length in relation to little width and value contrast against adjacent colors. Line has tremendous visual power. It can be close to impossible to see an edge between colors that are close in value, but the thinnest value-contrasting line between them creates an immediate separation.

Value and Image

Only value contrast makes objects distinguishable from their background. Figure-ground separation, the ability to discriminate objects from their background, does not require the presence of hue. Black-and-white drawings, printed pages, and film images are perfectly understandable. People with a deficit in color vision are functional in a seeing world because “color-blind” really means “hue-blind.” The degree of contrast between light and dark areas determines “readability,” or graphic quality. Black and white, the extremes of value contrast, create the sharpest images. The closer in value an image is to its background, the harder it is to see. When there is no value contrast—like an igloo in a snowstorm—there is no image at all.

Figure 4–13. Value and Image. Images are strongest when there is a sharp contrast in value between a figure and its background. Images are less distinct when the two are similar in value.

The same is true when color is present. Differences between areas may be emphasized by contrasts of hue or saturation, but the addition of color—even brilliant color—to an already powerful image does not change the force of that image. Instead, high color lessens the amount of time it takes to capture the viewer's attention. Only difference in value creates separation between figure and ground.

High value-contrast images are not always desirable. Very strong contrasts of dark and light induce lateral inhibition, so reading high value-contrast images over a sustained period causes eye fatigue. Superhighway signs in dark green and white, instead of black and white, provide good contrast at a slightly reduced level, decreasing the risk of eye fatigue—and accidents.

Figure 4–14. Hue, Value, and Image. Only contrast of dark and light determines image. Images remain the same whether in color or black and white. Photographs courtesy of Phyllis Rose Photography, New York and Key West.

Transposing Image

Value contrast makes objects distinguishable from their background. The placement of different values relative to one another within an image gives that image its individual identity. In order to transpose an image from one set of colors to another, the number and placement of values within the two images must be identical. If there are five values present in the first image, there must be five in the second, and the placements of light, medium, and dark areas must be the same in each. Scrambling the placement of values within an image creates a new and different image.

Figure 4–15. Maintaining an Image. To illustrate the same bird in different colors, the relationship of values within the images must be the same. Differences in hue alone do not change the image.

Figure 4–16. Changing an Image. The birds have the same configuration, but changing the placement of values within each one makes them look different.

Saturation

The third descriptive quality of color is saturation, or chroma. A saturated color is at its fullest expression of hue. It is undiluted in any way. It is at maximum chroma. Saturation is a comparative term that describes the contrast between dull and vivid. A series of steps of saturation, like steps of value, is linear and progressive. The beginning of a saturation scale is a color that is hue-intense. The end step is a sample so muted that its hue can barely be identified.

Brilliant colors are at a high level of saturation, but a vivid color is not necessarily a saturated color. Hues that contain a high proportion of yellow can be both vivid and saturated, but brilliant colors that do not contain yellow are more likely to be tints. A dazzling red-violet is likely to be a tint with a high level of saturation, not a saturated color.

Muted colors are at a low level of saturation. Any color can be illustrated in steps from full saturation to dull. As long as a sample can still be identified by its hue, it is a hue. Dull orange is still orange; muddy green is still green. Colors at the threshold between muted hues and tertiary colors provide a classic situation for disagreements caused by the way different individuals think about colors. Mary's “burnt orange” may be John's “brown.”

Value and saturation are easily confused. It is instinctive (and often correct) to think of dark colors as muted; harder to think of tints in that way, but any pure hue or tint can be reduced in its saturation—made less vivid—without changing its value. Red-orange can be muted to the color of light clay. The two contain the same hue and are equal in value, but one is a brilliant color and the other is muted.

Figure 4–17. The Same Hue and Value at Different Levels of Saturation.

Saturation: Diluting Hues with Gray

One way to change the saturation of a hue without changing its value is to dilute it with a gray of equal value.9 When a pure orange and a gray of equal value are the parents in a parent-descendant format, the middle interval, “gray-orange,” is duller than the orange, more chromatic than the gray, and identical in value to both—neither lighter nor darker than either of its parents.

Figure 4–18. Hues Diluted by a Gray of Equal Value.

Saturation: Diluting Hues with the Complement

A second way to dilute a vivid color is to add some of its complement. Adding the complement to a color to reduce its saturation is a time-honored technique in subtractive media. Adding a small amount of the complement mutes the color slightly; the more complement added, the more muted the color becomes.

When a pair of complements is arranged as a series of intervals moving toward each other, each step is reduced in saturation until the two reach the point where each loses its identity. Any pair of complements mixed to their midpoint create a tertiary color: a chromatic neutral.

A hue diluted by its complement changes in both saturation and value. Yellow and violet have extreme dark-light contrast, so a series of steps between them is a scale of light to dark as well as a scale of progressively reduced chroma. As the yellow becomes more muted and darker, the violet becomes more muted and lighter. A series between orange and blue displays a similar dark-to-light pattern, although the value difference between the two is less extreme. Green and red are roughly equal in value, so each becomes darker as it moves toward the other, with the center mix darkest of all.

Because every color has its complement, the number of muted colors that can be created by mixing complements in varying proportions is nearly infinite. These complex and sophisticated colors are especially common in the textile industries, both apparel and home furnishings.

Colors in high-end interior paint products often are marketed as “full-spectrum” to indicate that the muted color has been achieved by the addition of a complement rather than by the addition of black or gray. Because a wide range of colorants in the paint means that the finished surface will react with light in a multiple ways, full-spectrum paints are thought to provide a richer visual environment.

Figure 4–19. Six Spectrum Hues Diluted by Their Complements. Each pair reaches a different midpoint.

Theoretical Gray

Theoretical gray is a concept used by color theorists to characterize a perfect tertiary color: one of no discernible hue. Theoretical gray (if it existed) would be created by the mixture of any pair of complementary colors. If theoretical gray could be illustrated, the middle mixes of violet and yellow, red and green, and blue and orange would be the same. Visual logic does not allow us to imagine the middle mix of different pairs of complements as the same. Whether a series of steps between complements is illustrated with paints, papers, light or just imagination, every pair of complementary colors moves to a center that is distinct from other pairs.

The natural world offers a host of dazzling colorings. There are at least 350 varieties of parrots but only 17 varieties of penguins—and not all penguins are plain black and white. And although the exuberance of saturated color can be found everywhere on earth in flowers, fish, birds, minerals, and man-made materials, yet the complex, muted, and tertiary colors are by far the greater part of our surroundings. Soils and stones, forests, deserts, mountains, rivers, and seas, most wildlife as well as much of industrial production—nearly all are hues muted by a complement. Bauhaus painter Johannes Itten stated it eloquently: “Nature shows such mixed colors very elegantly, as when green fruits ripen to red, or leaves turn from green to brilliant red in the fall.”10

Figure 4–20. Nature Shows Such Mixed Colors Very Elegantly.

Tone

There is really no satisfactory definition for “tone.” The Oxford English Dictionary defines “tone” as a synonym of “value”: “a quality of colour; a tint, spec. the degree of luminosity of a colour, shade.” The Random House Dictionary of the English Language offers three contradictory definitions: “a pure color diluted by black or white,” “one hue modified by another” (as in “this is a blue tone, that is a greener one,”), and “a hue muted by gray.”11 Each definition means a modification of hue, but each means a different kind of modification of hue.

One word cannot mean variation in value, hue, and saturation interchangeably. If the word “tone” is to be used at all it is probably best to go with the most-used meaning: a color of reduced saturation. It seems clearest when used as a verb. To “tone down” a color means to mute it, to reduce its saturation. That phrase, at least, is familiar. No one ever says “tone up.”