CHAPTER 2

The Players and the Parts

An ad appeared some years ago for a major software company that showed a drawing similar to the one here, claiming that this is not a cow because it is a chart of the parts of a cow. In a healthy cow the parts don’t even know that they are parts; they just work together harmoniously. The ad asked would you like your organization to work like a chart or a cow?11

This is a serious question! Cows have no trouble working like cows, nor, for that matter, do any of us working as individual human beings, physiologically at least. So why do we have so much trouble working together socially? Is it because we are so obsessed with those charts?

Thinking Outside the Boxes

We talk incessantly about “thinking outside the box,” from inside our boxes, especially that chart (Figure 2.1). (It was first used in the eighteenth century and has been unstoppable ever since.)

Is its chart the organization? Is its skeleton the cow? Are the boxes of the chart the managers of the organization, and the lines between them their conversations? Or do these boxes just box us all in?

Of course, the chart has its uses. Like a map that identifies the towns, and the roads that connect them, the chart shows us how the parts and people are grouped into units, and how these are connected through formal authority—in other words, who reports to whom, and with what title. But just as a map fails to tell us about the economy and the society, so the chart fails to tell us how things happen in the organization, let alone why. Sometimes you can’t even tell from the chart what the place does for a living. What the chart certainly shows is that we are obsessed with authority, seduced by status—who’s on top and all that (see box).

FIGURE 2.1 An Organization

FIGURE 2.2 A reorganization

Here Comes Yet Another Reorganization Now have a look at Figure 2.2, compared with Figure 2.1. It shows a reorganization. Did you notice the difference? The managers who have been shuffled around the chart certainly do: each has a new title, or a new “superior,” or some new “subordinates.” (What awful terms.) There must be more to organizations than all this labeling and bossing. If seeing is believing, we had better see our organizations differently.

Reorganizing is so popular in organizations because it’s so easy. All you need is a piece of paper and a pen—better still a pencil, with a good eraser, if not a screen with a great big DELETE button. Accounting goes here, marketing goes there, and so on. Travis becomes the Minister of Transport, Daphne becomes the Minister of Defense. Off they all go . . . into utter confusion. “We have trained hard, but it seemed that every time we were beginning to form up into teams, we would be re-organized. I was to learn later in life that we tend to meet any new situation by re-organization: and what a wonderful method it can be for creating the illusion of progress while producing confusion, inefficiency, and demoralization.” (This is usually attributed to Petronius Arbiter of the Roman Navy, 250 BC, but, apparently, was actually written around 1948.)

Imagine, instead, an architectural reorganization: shuffling where people sit. This may take more effort, for the designers at least, but it can result in less effort for everyone else. Suddenly Enid from Engineering finds herself sitting next to Max from Marketing. Rather than continuing to complain about each other, now they talk to each other—at the coffee machine, at least. No boss in sight. That’s a reorganization!

The Principal Players

Cows have real parts, like lungs and livers, brains and bowels. These do real things (compared with a sirloin steak, which does nothing for a cow, except end its life). Organizations, likewise, have real parts, with players who do real things. Here are the main ones.

• The operators do the basic operating work of the organization: producing the products, rendering the customer services, and whatever supports these directly. On a hockey team they score the goals, stop the shots, maintain the equipment. In a restaurant they serve the sirloins and park the Passats. In manufacturing companies they are the purchasing agents, machine operators, salespeople, and so on.

• The support staff support the operations indirectly. They develop the information systems, provide the legal services, welcome visitors at the reception. Count all the support services in a university—libraries, placement, payroll, residences, alumni relations, human resources, faculty club, and many more—so many that you have to wonder if there’s any room left for the professors. (The term staff is used in other ways as well, sometimes for employees in general, such as the staff of a law office, for certain operators, including physicians in hospitals, even for the senior management, as in the chief of staff in the military.)

• The analysts use analysis to control and adapt the activities in one way or another: they plan them, schedule them, measure them, budget them, and sometimes train the people who do them—they just don’t do them themselves. Together, these analysts are sometimes referred to as the technostructure of the organization. As we shall see, some organizations have hardly any analysts and support staff while others are inundated with one or both.

• The managers oversee all this, having formal responsibility for some particular unit in the organization, or the whole of it. A unit is some part of the organization designated in its formal structure: an emergency room in a hospital, a pastry kitchen in a restaurant, a forward line in hockey. In all but the smallest organizations, these units are usually shown in the chart stacked upon each other to form the official hierarchy of authority. Soldiers are thus grouped into squads, squads into platoons, and on into companies, battalions, brigades, and divisions, until the final grouping into armies. Each has its own manager, from sergeant to general. Elsewhere, we find managers with titles such as coach in hockey, bishop in religion, director of a film. The manager in charge of a whole business is usually called chief executive officer (CEO), to whom may report various other members of the C-suite: COO (operating), CFO (finance), CLO (learning), and so on. Now, aping business, CEOs are springing up in all kinds of other organizations. (At least the head of the Roman Catholic Church is still called Pope.) All managers, beyond overseeing the work of their unit, connect it to the outside world. A sales manager meets customers; the Pope addresses the faithful in Saint Peter’s Square.

• The culture is the system of beliefs that permeates the organization, providing a common frame for all the players, ideally to breathe some life into the skeleton of the structure. Just as every person has a personality, so too does every organization have a culture, its way of doing things, ranging from rather indistinct to highly compelling. (Beyond this, we find cultures in occupations, such as medicine, in functions within an organization, say sales compared with marketing, and, of course, in nations, say German compared with Italian.) For many years, Ed Schein has described organizational culture on three levels.12 At the surface are the artifacts that symbolize the place visibly (the Apple logo on a laptop, the cross for the Catholic Church, the Statue of Liberty for the United States). A bit deeper are the espoused values, public statements of intent (the Ten Commandments or some other mission statement). And most deeply embedded, sometimes unconscious, are the basic assumptions that can be found in the behaviors of the players (maintaining top quality, get everything done quickly). Of course, in a healthy organization the espoused values are manifested in the basic assumptions, but not always. For example, greenwashing is the name given to empty statements about responsibility to the environment.

• The external influencers seek to shape the behavior of the organization from the outside, for example, the unions, local communities, and other special interest groups that lobby the big corporations and these corporations themselves that lobby governments. Greenpeace lobbies at the COP (UN climate change) conferences, and the Rio de Janeiro fans support the Flamengo team. Many of the influencers of businesses are now referred to as stakeholders, in contrast to the owners of the stock, who are called shareholders.13 Together, all these influencers form an external coalition that may be passive, actively dominated by one group, or divided among several.14

FIGURE 2.3 The Players and the Parts

An Earlier Logo

Books are written in linear order, every single word in a single sequence, from beginning to end. This may be fine for a diary, but in other books, this linear order has to describe something that is not linear at all—here, the nature of organizations. Diagrams, figures, and other images can help us to see past this, by illustrating the woven reality. So be prepared for many images.

For the original version of this book, I created a diagram to locate these players (Figure 2.3). The operators were put at the base and the line managers—bottom to middle to top (called strategic apex)—were put above them, with the analysts and support staff to either side. Later I added culture as a kind of halo, and the influencers, all around. This became a kind of logo for the book, and people had a field day with what they saw: lungs, a fly’s head, a kidney bean, female ovaries, an upside-down mushroom, and worse.

When I began work on this new edition, however, I realized that in this figure I had acceded to the conventional, hierarchical view of the organization. But instead of dropping the logo from this book, I decided to drop the hierarchy in the logo, as you will see by shaping it in various ways to demonstrate how organizations differ, some looking more like the original drawing, others flatter, or rounder.

Chains, Hubs, Webs, and Sets

Now let’s look at some connections between the parts, as chains, hubs, webs, and sets, to help explain how organized activities flow, or don’t.

Consider a wedding. The event itself is a hub, with the guests coming from different places to a central place. As the diners line up at a buffet table, they form a chain, advancing in single file from one dish to the next. Then they take their seats at a table, one of a set of them around the room. When the dancing starts, however, the place becomes a web of interactive activity, as the guests chat and move every which way.

Seeing the Organization as a Chain

These days, the most popular depiction of the organization is as a chain, where work is seen to flow in a linear sequence. For example, automobiles are assembled as they move down the line, with the parts being added one after another. And how about a double play in baseball: from shortstop to second base to first base.

![]()

Michael Porter popularized the value chain as the common way to organize.15 Supply chain has also come into popular usage, to describe logistics in organizations. But while books may be linear, much that goes on in organizations is not. In universities, do professors of strategy connect in any kind of chain with their colleagues in marketing? How about pediatrics and geriatrics in a hospital? (A long chain indeed.) Do the stores of even a retail chain work as a chain? Maybe, therefore, it’s time to break the chain—into hubs, webs, and sets.

Seeing the Organization as a Hub

A hub is a coordinating center, a focal point of activity. We call an airport a hub when it is used extensively to transfer passengers between flights. But every airport is itself a hub to which flights and passengers come and from which they go, likewise a hospital for the patients and the staff. Indeed, within the hospital, for the most part, each patient is a hub. Rather than moving them around, most of their services—nursing, medical, food, oxygen—come to them. Likewise with the assembly of large aircraft: it can be easier to move the parts to the plane than the plane to the parts.16 Even a manager can be seen as a hub: watch a football coach during practice.

Seeing the Organization as a Web

Visit the design studio of an architectural firm and, like those dancers at the wedding, you will find people interacting in all kinds of ways, not in the neat order of a chain or the focused flow of a hub. Webs, or networks, are open-ended movement of people, information, and/or materials, with no fixed sequence or center. They move flexibly, variably. When you don’t quite know where you are going (unlike that double play in baseball), or where the center is (unlike that patient), but you do need to work closely together, you had better organize as a web. This is why the World Wide Web is called a web.

Seeing the Organization as a Set

But what happens when people don’t have to work closely together—say, across pediatrics and geriatrics in the hospital, strategy and marketing in the business school, even the divisions—appropriately named—in a conglomerate company, let alone the stores of a retail chain. Hardly a hub, a chain, even a web. But a set: The parts are “loosely coupled,” barely connecting with each other. They share common resources. (Hence the university has been defined as a collection of professors who share a parking lot.)

Even when it may look like they are working together, these people may be working apart. Watch an open-heart surgery (as a doctoral student of mine once did, for five hours): the surgeon and the anesthesiologist may not exchange a single word. That is because each knows exactly what to expect of the other. Or how about an orchestra during performance? The players barely look at the conductor, let alone each other.

Lise Lamothe, who studied medical specialties in her doctoral thesis, found that cataract surgery worked like a chain of steps, rheumatology more like a hub (with the treating physician seeking consultations from other specialists), and geriatrics like a web (where teamwork is required for the multiplicity of disorders—one chief of geriatrics in a Montreal hospital used to claim that a physiotherapist was their best diagnostician).17 Of course, all together in a hospital they constitute a set.

For some years, when I wanted to understand how a particular organization worked, holistically, I brought together a few of its people to draw an organigraph: a depiction of how work flows through the place, identifying the role of each of its major players. The notions of chains, hubs, webs, and sets were particularly helpful for this.18

Where to See the Manager?

Looking back at the diagrams of the chain, hub, web, and set, ask yourself where to see the manager of each?

In a chain, the answer seems obvious. On top. On top of the horizontal chain of operations is built the vertical chain of command—a manager for each link and a manager for all managers. So the chart does have its place after all (as we shall see in Chapter 8), however limited that may be (as we shall see in Chapters 7, 9, and 10).

In a hub, however, a manager who is on top of it is out of it (in both senses of the term). The manager has to be in the center, where the action is. Perhaps that is why the executive directors of hospitals (hubs) tend to be located on the main floor, whereas the CEOs of mass production (chain) corporations tend to sit on the top floor. About women managers, in The Female Advantage: Women’s Ways of Leadership, Sally Helgesen wrote that they “usually referred to themselves as being in the middle of things. Not on top, but in the center, not reaching down, but reaching out.”19

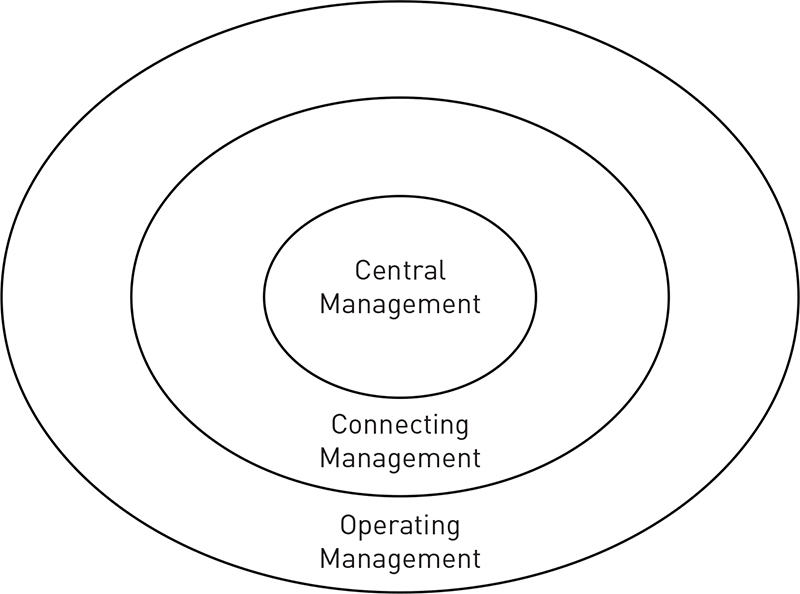

In a hub you can replace top, middle, and bottom management with concentric circles: put the chief in the center, surrounded by connecting managers, who link to the operating managers facing the surrounding world (Figure 2.4).

In a web, however, if you put the manager in the center, you “centralize” it—that is, turn it into a hub. Instead of people interacting every which way, they focus on the boss. Put its manager, instead, on top of a web and, again, you take him or her out of it. So where to find the manager in a web? Everywhere—along every line and at all the nodes. In other words, they have to get out of their offices and sit in on all sorts of meetings, join various conversations in the halls, experience what’s happening on the ground. Not to micromanage, but to know what’s going on and thus be ready to act when something goes wrong.

Steve Jobs spent his mornings in a design lab at Apple.20 What was the CEO of this huge, high-tech company doing there, instead of reading financial statements in his office like a proper CEO? He was using his best talent to help create more shareholder value than had any other company in history, including all those run by the number crunchers.

Moreover, in a web, managing can be, not only everywhere, but everyone. All kinds of players can perform tasks that are normally carried out by the managers who sit atop the chains or at the center of the hubs. (We shall return to this distributed management later in the book.)

In a set, with the people working largely on their own, the managers not only can be out of it, but may do better by largely staying out of it—instead exercising oversight. For example, no surgeon in an operating room relies on a manager to give instructions or otherwise to exercise control. Once the resources are allocated (say, in the form of budgets), people know what they have to do and just get on doing it.

FIGURE 2.4 Managing Around

So let’s not tie all our hubs, webs, and sets in chains: all four of these are different yet legitimate ways to see and manage organizations. With these re-views of the parts and the players completed, let’s turn now to some of the main processes in organizations.