CHAPTER 11

The Four Together

How basic are these four forms? Basic indeed. One is personal. One is programmed. One is professional. One is project. Are they real? That, as we shall see, depends on what we mean by real.

Four Forms Forever

These forms can be seen to go way back, to when humans first became organized. The project organization, of “our age,” is probably the oldest, when Homo sapiens hunted collaboratively in packs (i.e., teams). As people settled into communities, leadership in the form of the personal organization arose. We have already seen an example of the programmed organization in ancient Mesopotamia, where there was also suggestion of the professional one: “Skilled artisans were frequently recruited from distant regions. Workers were organized into guilds by specialty.”83

As for the heyday of the forms, if today is the era of the project organization, then perhaps that of the personal organization was when monarchs and feudal lords ruled. The Industrial Revolution brought in that of the programmed organization, which likely persists as highly prominent, even if the Personal Enterprise may be the most ubiquitous.84 (Think of all the sovereigns, autocrats, entrepreneurs, and tycoons. “Master” is a heading in my thesaurus for twenty-one categories of this, which cover a page-and-a-half! We remain obsessed with leadership.) There may not have been a heyday for the professional organization, but it did spread as the professions established themselves in the twentieth century.

Heydays of structural fashion notwithstanding, all four forms are prominent today, and will remain so, as suggested by the many current examples in the last four chapters. How do you identify a form that might fit when you encounter an organization (see box)?

Summarizing the Forms

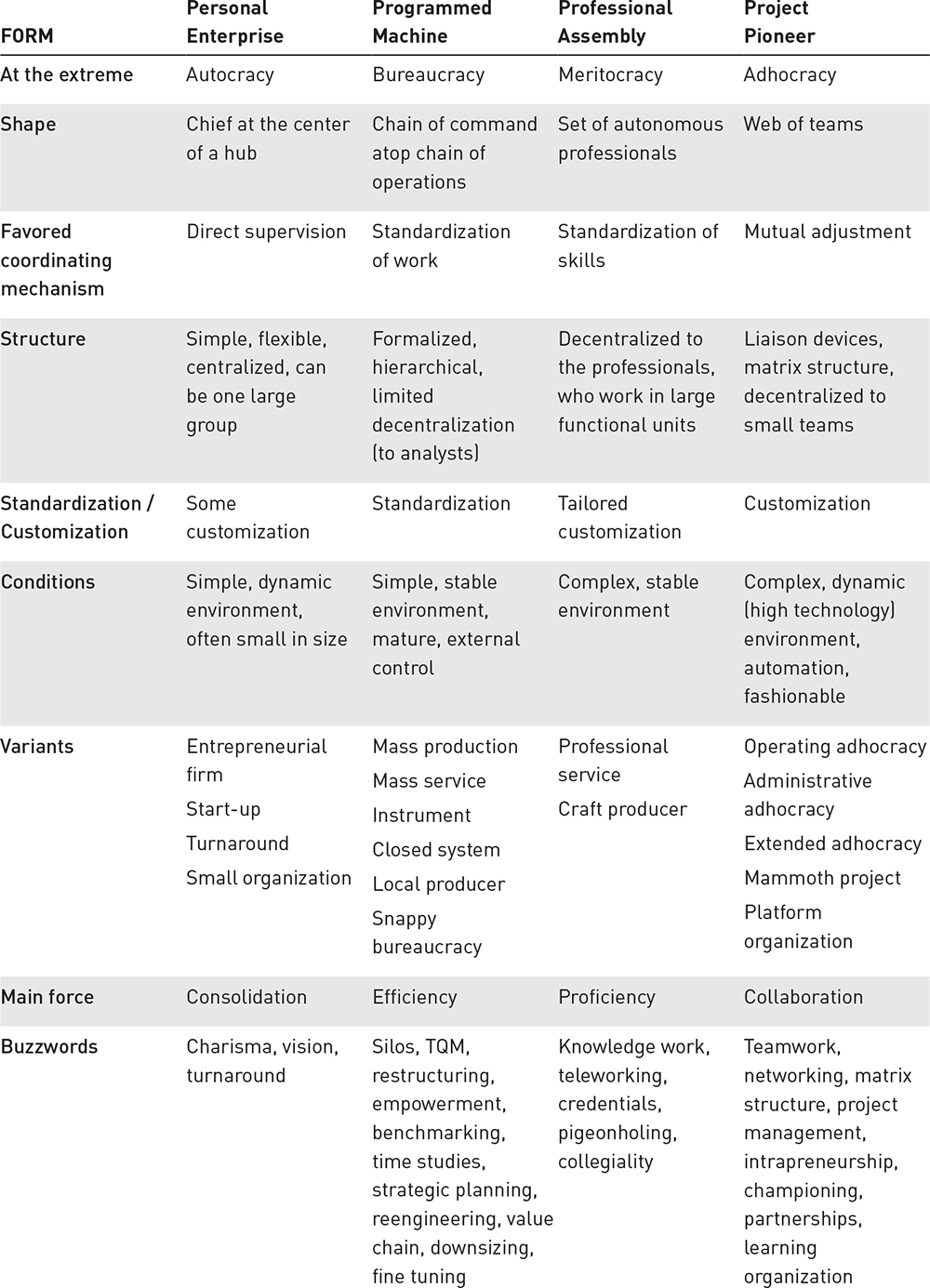

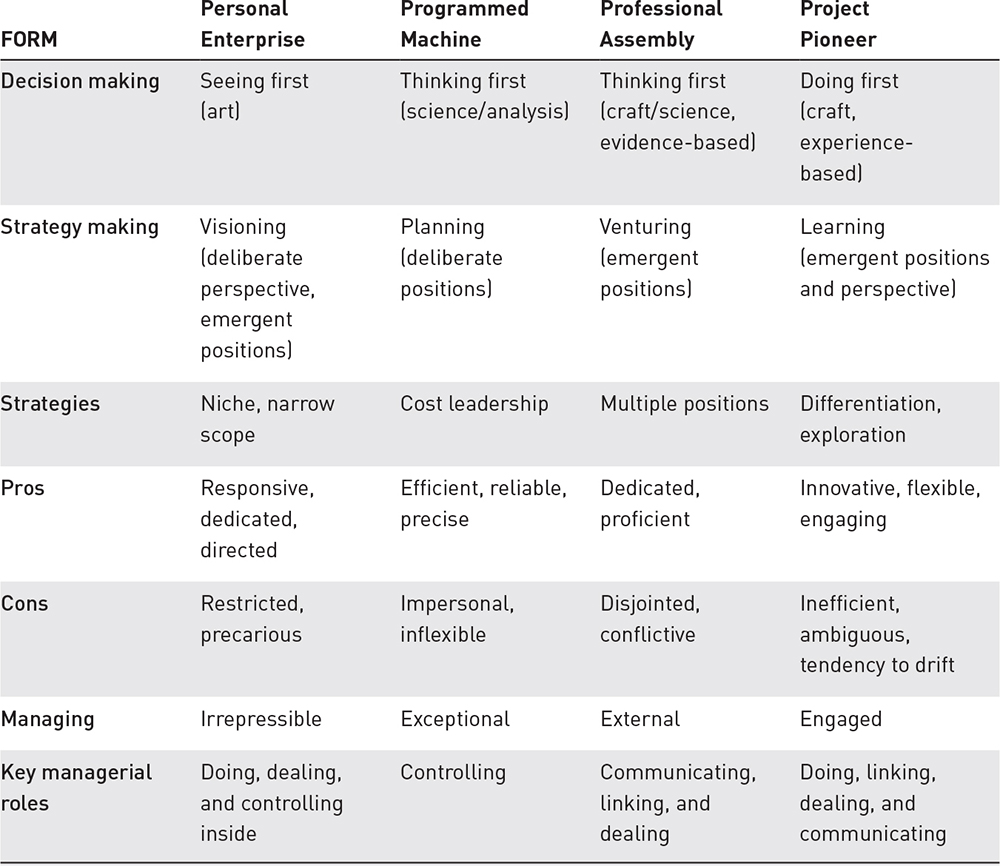

We know a good deal about these four forms: the structures they use, their processes to form strategies, the nature of their managers’ work, the problems they tend to encounter, and so on. Table 11.1 summarizes this. For the most part, the table can speak for itself (extrapolated from comments in the last four chapters), save for a few explanatory words below, except for two of the characteristics that will be discussed at greater length: the strategy processes and managerial work in each of the forms.

Table 11.1 The Four Forms of Organization

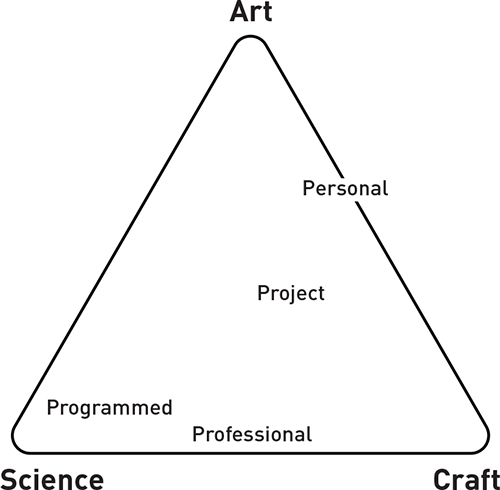

Figure 11.1 plots the four forms of organization on the triangle of art-craft-science, with the Personal Enterprise shown closest to art (the vision of the chief) and the Programmed Machine closest to science (in its use of analysis), while the Professional Assembly functions between science and craft (evidence and experience), and the Project Pioneer is perhaps closer to craft (experience-based teamwork), but with the creative use of art as well.

FIGURE 11.1 The Forms on the Triangle

Buzzwords (tools, techniques, concepts) are listed under the form where they seem to be most commonly found—for example, charismatic leadership in the personal organization and knowledge work in the professional one. That so many are listed under the Programmed Machine is another indication of the extent to which this form dominates our thinking about organizations.

Strategy Formation in the Forms

Chapter 3 introduced four approaches to the development of strategy, labeled planning (deliberate, about positions), visioning (deliberate, about perspective, with positions emerging), venturing (emergent, about positions), and learning (emergent, about positions and perspective). These map remarkably well onto the four forms of organizations—in fact, they may be the most revealing of the differences between them.

Visioning Strategy by the Chief of the Personal Enterprise

In the Personal Enterprise, strategy tends to take the form of the vision of the chief, as in the case of a Steve Jobs at Apple. Such a vision can be highly deliberate, and tightly integrated. As a strategic perspective, it serves as an umbrella under which specific strategic positions can emerge (at Apple: laptops, iPads, watches, etc.). In the Personal Enterprise, these strategies are often found in niches that enable the organization to escape the competition of the established machines—for example, a restaurant that focuses on organic offerings.

Planning Positions in the Programmed Machine

As noted, machine organizations have long been the champions of Strategic Planning, whereby senior managers are expected to formulate deliberate strategies for everyone else to implement. But as indicated in Chapter 8, all too often strategic planning reduces to strategic programming, namely extrapolating the consequences of a strategic perspective already in place (positions to add, expenses to cut, and so on). Put differently, numbers tend to dominate, often with barely a new idea, let alone a renewed vision, in sight. Here, then, the strategic plans, so called, reduce to action plans, backed up by performance controls.85

Where, then, does the strategic perspective come from? Frequently from an earlier time, as a Personal Enterprise, when the founding chief developed it. Or else, not uncommonly, it has been copied from other organizations in the industry, as a me-too strategy.

Of course, a machine can always be fine-tuned: there is always room for new strategic positions (adding Egg McMuffin to the McDonald’s menu). But don’t look for strategic revolutions here, at least so long as the organization maintains its machine characteristics. Change an element of a tightly integrated machine and it can disintegrate.

Venturing Positions at the Base of the Professional Assembly

Even more me-too are the overall strategies of the Professional Assemblies. Because so much of what they do is regulated by their common professional associations, these organizations tend to be the local providers of generic strategies. Just compare your local general hospital with others across town, or your local university with others around the world: it may well be distinguished by where it provides its services more than by what services it provides.

Janet Rose and I tracked the strategic activities of McGill University across a century and a half of its history.86 In all that time the university managed to close only one faculty—Veterinary Medicine, which lasted barely a decade and a half. The university proved to be the sum total of every faculty it ever had!

Yet lurking beneath the surface of many a standard-looking professional organization can be all sorts of unique strategic positions, championed by the operating professionals. Seen from a distance, McGill has all the usual faculties—Arts, Science, Medicine, Management, and so on. But look more closely within them, and you will find many unique programs, such as our International Master’s Program for Managers (impm.org), which has none of the usual courses in marketing and finance, nor young students sitting in U-shaped classrooms discussing cases. Instead, midcareer managers sit at roundtables where they learn from their own experience, in modules labeled reflection, analysis, collaboration, worldliness, and change.

Such ventures abound in Professional Assembles, but few come from their management: most are championed by the operating professionals within their own specialties. Can the sum of all such ventures really be said to add up to a strategy for these organizations? Yes indeed, because together they determine how it positions itself in its environment.87 Just as it assembles its people into its structure, so too does the Professional Assembly assemble its strategic positions into its overall strategy.

Learning Strategies across the Project Pioneer

Strategy is learned in the Project Pioneer as its teams build on their experience. Of course, strategies are learned in the Personal Enterprise as well—it, too, can explore—but through the personal experience of an individual chief. Hence its strategy is likely to be more integrated than that learned from the various team efforts of the project organization.

We studied the strategic history of the National Film Board of Canada, an agency of the federal government of Canada that had become renowned for its short documentary films.88 Here was the quintessential adhocracy, each film a project in its own right. At one point, the NFB suddenly branched into feature films, a brand-new strategic position, with a rather different strategic perspective. Where did this come from? Not from any planning process of senior management— in fact, it came as a surprise to that management, even to the filmmakers responsible for it.

A single film ran too long, and not being able to distribute it in the NFB’s usual ways, it was marketed as a feature film in theaters. Other filmmakers took notice—“Why not me?”—and before long, some were making feature films of their own, thus taking the organization to a new strategy. Talk about a strategy forming without being formulated!

Throughout the almost forty years that we tracked the strategies of the NFB (as patterns in the films that it made), the organization went through remarkably regular cycles of convergence and divergence: about six years of clear strategic focus (for example, in series made for television, with the advent of this medium), followed by about six years without such focus. Interestingly, many of the NFB’s most creative successes came in the latter periods. Strategic focus can sometimes get in the way of creativity in a project organization, by discouraging the pursuit of novel insights. Of course, without such focus, there is the alternate danger of strategic drift—single projects taking the organization off in all directions.

Inspired by these findings, we developed a grassroots model of strategy formation (see box). This may be overstated, but perhaps less so than the widely accepted hothouse model of strategy formulation.

Managing in the Forms

As described in Chapter 3, managing may be managing. But it does vary in the four forms.

Irrepressible Managing in the Personal Enterprise

Management in the Personal Enterprise is essentially the chief, irrepressibly, the hub around whom everyone and everything revolves. There may be other managers in particular units, but they tend to take their cues from the chief.

Go into an entrepreneurial company, small or large, and watch the boss, likely being watched by everyone else. “Now listen to me slowly,” said the founder of a large chain of supermarkets at a meeting of his executive committee. Little restrains the chief in this organization of minimal structure and few standards, sometimes not even operational planning. Some years ago, I asked a manager in a famous retail chain why they were so often out of stock. “Because the founder hates planning,” came the reply.

Micromanaging is bad, right? As noted, if you are the big boss, stick to the big stuff and leave the details to others. This advice itself can be bad, especially (but not only) in the Personal Enterprise. The big picture has to be painted by little brushstrokes, with clues found on the ground. Hence, managing on the ground need not be micromanaging. The best entrepreneurs are masters at consolidating operating details into comprehensive strategic visions. Rather than formulating to implement, they cycle back and forth between concrete actions and conceptual inferences: they do in order to think, in order to do, in order to think . . .

In terms of the model of managing introduced in Chapter 3, while all managers have to manage on all three planes—of information, people, and action—in the Personal Enterprise we can expect to see more activity on the action plane: more doing on the inside and more dealing on the outside, alongside considerable controlling within the organization on the information plane.

As for the conundrums, of greatest concern here are likely to be: (a) the dilemma of delegating: how to delegate when so much of the relevant information can be personal, oral, and privileged? and (b) the clutch of confidence: how to maintain a sufficient level of confidence without crossing over into arrogance?

Managing as Fine-Tuning the Programmed Machine

If the chief is key in the Personal Enterprise, then the structure is key in the Programmed Machine. Here, with the help of staff analysts, the managers—top, middle, and bottom—program the strategies, which tend to remain rather stable. This means that the managers have to fine-tune their bureaucratic machine, continuously, especially to avoid disturbances. Since “uncertainty is the biggest enemy,” the lid must be kept tight on the conflicts that arise in these structures.

This was crystal clear when I spent a few days with the managers of a large Red Cross refugee camp in Tanzania, on the borders of Rwanda and Burundi, shortly after the atrocities that occurred in those countries. Here was conventional managing in a most unconventional setting. All was eerily calm in the camp, everything remarkably programmed. Because these camps could blow up at a moment’s notice, their managers had to be obsessively responsive to the least little spark.89

To keep the organization on course, to avoid disturbances, to contain conflict, the managers of the Programmed Machine thus seek to maintain it as closed as possible—whether by a foreman to keep disruptive visitors out of the factory or by a CEO to keep meddling board members at arm’s length. Hence the role of controlling, internally, on the information plane, is pivotal.

When disturbances do appear—when the programs don’t go according to plan—management by exception comes to the fore. The managers must bring the organization back on course. Thus, no matter how programmed the rest of the machine, management itself (really in all four forms) has to function as adhocracy—in other words, flexibly and collaboratively.

As for the conundrums, here four are of particular concern: (a) the labyrinth of decomposition: where to find synthesis in a world so decomposed by analysis? (b) the quandary of connecting: how to keep informed when managing by its very own nature removes the manager from the very things being managed? (c) the mysteries of measuring: how to manage something when you can’t rely on measuring it? and (d) the riddle of change: how to manage change when there is an overriding need to maintain continuity? And we mustn’t forget the clutch of confidence: with so much control up the hierarchy, it’s rather easy to slip from confidence into arrogance.

External Managing in the Professional Assembly

Hierarchy takes a different form in the Professional Assembly. As noted, the professionals look up their own hierarchy of status, while the managers look down their hierarchy of authority, to the less professional staff. Thus do they pass each other like ships in the night.

What the managers here do, at every level, is support the professionals more than supervise them. In a hospital, for example, the executive director as well as the medical chiefs are expected to ensure a steady inflow of funding, whether from donors (e.g., for new equipment) or from government departments (e.g., for bigger budgets), while at the same time holding these same influencers at bay, so that the professionals can work with minimal distraction. Faced with governmental officials and board members who don’t appreciate the difference between meritocracy and bureaucracy (“Measure those death rates.” “Control those workers like I control my truckdrivers.”), managing in the Professional Assembly requires a delicate balancing act of drawing the outside influencers in while keeping them out.

Delicate balance is also required to deal with the many jurisdictional disputes that arise in these organizations—the conflicts across the categories. Hence, to manage a Professional Assembly is to recognize the asymmetry of having to advocate out while reconciling in. Facing out, the manager is expected to advocate for the whole organization, yet turning around, they have to face many professionals advocating for their own interests.90

This brings to the fore the external roles of managing: communicating on the information plane, linking on the people plane, and dealing (especially negotiating) on the action plane. The managers of the Professional Assembly have to link more than lead and deal more than do, while internally, they have to convince more than control and inspire more than empower. Yet an astute capacity to do all this can render these managers highly influential, even though they may lack the power of managers in the other forms.

Two conundrums are central to this managing: (a) the labyrinth of decomposition: where to find synthesis in a place so decomposed by analysis? and (b) the riddle of change: how to manage change when there is the need to maintain continuity?

Engaged Managing in the Project Pioneer

In the three forms of organizations discussed above, the work of managers is rather differentiated from that of nonmanaging. Not here. As we have seen, managers in the Project Pioneer commonly engage in the project teams, while many of the experts commonly engage in the process of managing, for example, by creating the precedents that become strategies. To use the term that has become popular of late, here we find distributed managing—yet another blurring of the conventional categories.

But with power so decentralized to project teams that can drift off in any direction, the senior managers may have to consolidate disparate actions into coherent strategy—to nudge the teams toward what seems to be working best. Andy Grove favored this word when writing about his stewardship at Intel: his inclination to coax behavior in a preferred direction.91 You don’t nudge workers in the personal and machine organization so much as direct them. And even trying to nudge the skilled people of a professional organization anywhere can be tricky. But in an organization that pioneers all kinds of projects, nudging is necessary to move forward, collaboratively.

If doing (on the projects themselves) can be a pivotal inside role for the managers of the Project Pioneer, then linking and dealing are pivotal roles externally. Managers at all levels of the project organization are very much salespeople, as the partners of adhocratic architecture and consulting firms know full well. Since the project work comes and goes, the managers have to smooth out the bumps by ensuring a somewhat steady stream of new projects. Moreover, because networking is so central to the functioning of these organizations, communicating on the information plane, internally as well as externally, takes on special importance here.

Three managerial conundrums are of special significance here: (a) the syndrome of superficiality: how to get in deep when there is so much pressure to get it done; (b) the predicament of planning: how to plan, strategize, just plain think, let alone think ahead, in such a hectic job; and (c) the ambiguity of acting: how to act decisively in a complicated, nuanced world.

To summarize: in the Personal Enterprise, the chief is the heart and soul of the place, while other managers—if there are others—largely respond to him or her. In the Programmed Machine, the managers fine-tune the systems to keep the organization running smoothly, especially by dealing with unexpected disturbances. In the other two forms, where so much power resides with individual professionals or teams of experts, the managers do not control so much as connect, to link people and projects to each other as well as to the outside world, with much of the regular managing distributed.

The Forms for Real

Are these four forms real? Do they exist? What’s real? We have been seeing words and figures on paper or screen. They are real, in their own way, even if not part of the “real world.” But show me anything in the real world, and I’ll show you something that is real and unreal in its own way.

Reality is too big for our little heads. So we use simplifications of reality to deal with it, impressions of reality: ideas, concepts, frames, models, forms, and theories. These help to explain the reality we encounter. Hence, our choice is not between, let’s say, theory and reality, so much as between alternate theories of reality. And this pertains to a manager making a decision as much as to you reading this book. Logically, we choose the theory that is most useful under the circumstances—not the best, but the best available—no matter how imperfect it may be. So, if I have been doing my job well, these forms do exist after all, in your head, there to help you understand and design organizations.

I have offered many examples of the forms throughout this discussion. But if you probe into any of them, you will find anomalies. For example, the players in football—the quintessential programmed sport—require considerable training. And there are pockets of adhocracy in any bureaucracy (try the advertising department), just as there are pockets of bureaucracy in the most creative adhocracy (someone has to staff the mail room). Doctors Without Borders assembles professional hospitals as projects in disaster zones, while TV soap operas sometimes look as programmed as cars coming off an assembly line.

With all these anomalies, should we reject the four forms after all? Not at all, because anomalies are not only real, but common. No organization can be a perfect match for any one form, although quite a few come remarkably close. So far, much of this book has been about them—it has been doing its own pigeonholing. Here, however, we reach a turning point: what follows takes us past the four forms, to open up our discussion.