CHAPTER 13

Three Forces for All the Forms

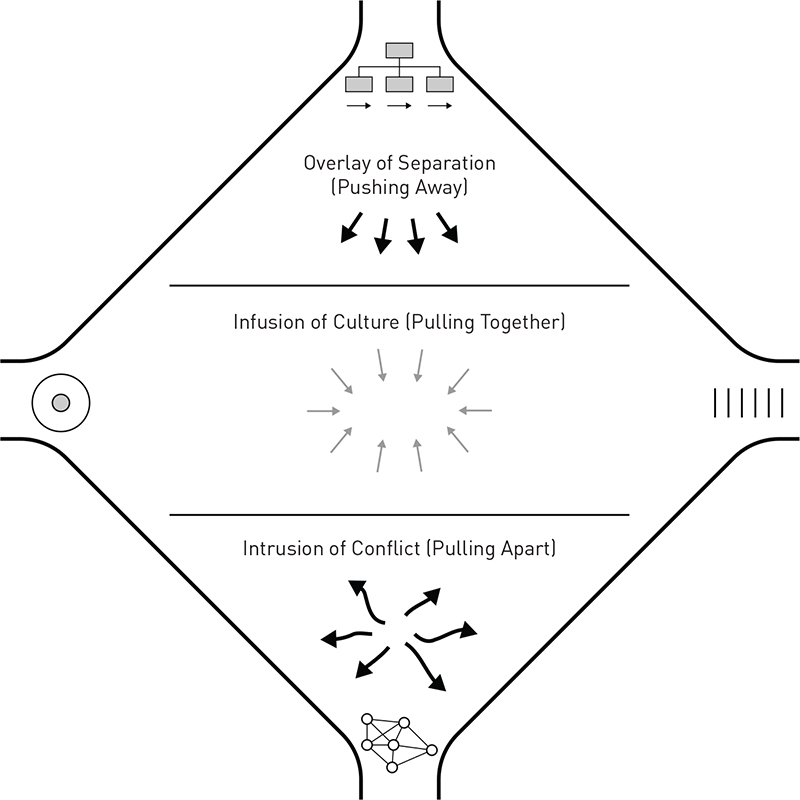

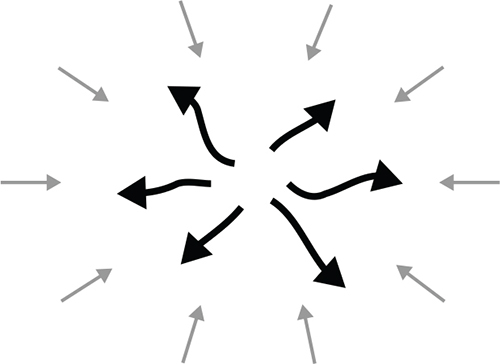

Beside the force for each of the four forms are three more forces for all four of the forms, catalytic in nature. One of them, the infusion of culture, tightens up the structure, by encouraging people to pull together, and the other two loosen it up, the overlay of separation by pushing the units away from each other, and the intrusion of conflict that pulls people and units apart from each other. As shown in Figure 13.1, separation is overlaid from above, culture permeates throughout, and conflict acts as a kind of underhand.

The Overlay of Separation (Pushing Away)

Part II of this book described the division of labor, namely how positions in the organization need to be differentiated—separated from each other—and then how they need to connect by the various mechanisms of coordination. Then, in Chapter 5, we discussed unit grouping, whereby these positions are combined into units that are separated from each other by the silos and the slabs, and hence require being brought together by various lateral linkages, systems of planning and control, and the like.

FIGURE 13.1 Three Forces for All the Forms

But sometimes there is the need to encourage further separation—to grant units greater autonomy within the structure. To do this, the organization turns to a loose mechanism of coordination, the standardization of outputs: power to make many decisions is delegated to these units, subject to achieving the results imposed by the central management. This is the overlay of separation—laying separations over the existing structure. A telephone company that offers land lines, mobile services, and internet connectivity may be inclined to establish a separate division to deal with each.

The Infusion of Culture (Pulling Together)

As discussed in Chapter 2, every organization has a culture, its way of doing things. A research lab just doesn’t feel like a bank, or, for that matter, sometimes even one research lab from another. If grouping is the skeleton of the organization and systems are its flesh and flows, then culture can be its spirit. Can be, because some cultures are ordinary, indistinct, like several supermarket chains where I live. (They can be described as having an industry culture. Likewise, there are occupational cultures, such as in engineering, and, of course, nations are often described as having their own cultures—say, German compared with Italian.)

Organizations with indistinct cultures are like people with indistinct personalities—they are more flesh and bones than heart and soul. But some organizations are distinct: they have their unique ways of doing things. This can render their culture compelling, thus infusing their structure with soul, much as a dye infuses a clear liquid with color. The story is told of three bricklayers. When asked what they do, one says that he is laying bricks, a second that he is building a church, the third that he is creating a monument to the almighty. It is in the third where the people pull together, as members of a community more than just employees who go to work. We can call this collective spirit communityship—a word we can use to get past our fixation on leadership.92 For example:

Bees and ants are unable to survive in isolation, but in great numbers they act almost like the cells of a complex organism with a collective intelligence and capabilities for adaptation far superior to those of its individual members.93

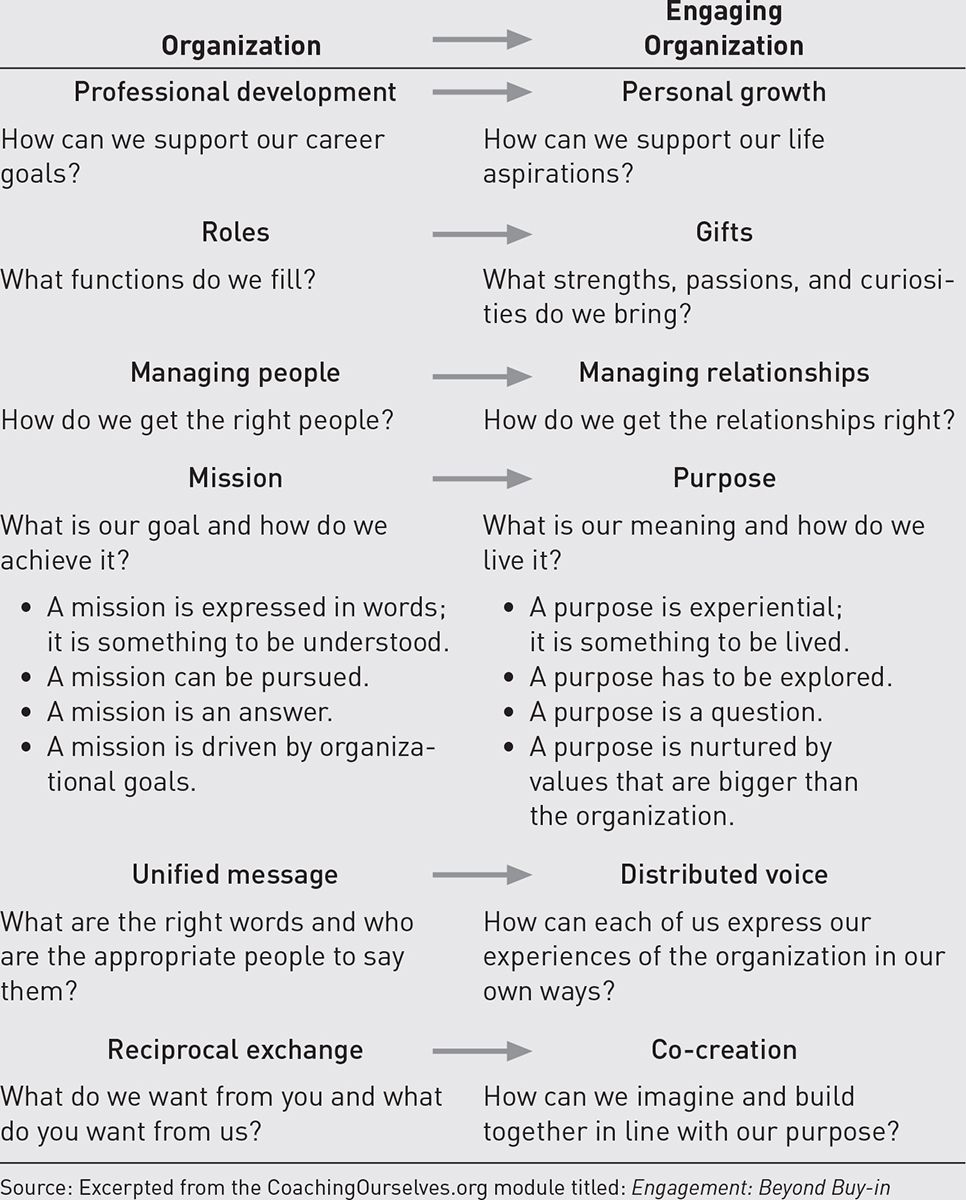

Synergy is a word for this phenomenon, the 2 + 2 = 5 concept: that the parts together produce more than they would apart. Organizations generally function more effectively when people work in compelling cultures that reduce their status differences. Whether you are sweeping the floors or managing the office, you are recognized for doing your part to make the organization great. See “The Engaging Organization” box to appreciate how compelling cultures work.

While people of other organizations may look outward to what comparable ones are doing, the people in these organizations look inward to the enthusiastic pursuit of its own mission. This could explain why some sports teams with no star players come out of nowhere to win championships. The regular players just played together with exceptional energy: 2 + 2 = 5. Money can buy stars, but it can’t buy conviction. Likewise, sometimes we walk into a hotel or a school and the place just feels different. The people are attentive, responsive, and energized; they serve well because they themselves are respected by their own management (see “A Tale of Two Hotels” box below).

The Development of a Compelling Culture

There are three stages in the development of a compelling culture: founding, diffusing, and reinforcing.

Stage 1: Founding with a sense of mission, often around a charismatic leader, who creates something special, exciting. This is much easier to do in a new organization, unconstrained by procedures and traditions, when people are able to develop close personal relationships—to pull together. In contrast, doing so in an existing organization, with the beliefs and procedures already established, is far more difficult, although sometimes a major event—the arrival of a charismatic leader, a crisis demanding major change—can enable the organization to suspend its usual ways and build culture anew.

Stage 2: Diffusing the beliefs through precedents and stories. As the members collaborate in making decisions and taking actions, precedents are established that can become traditions. Stories are told about inspiring events; the best of which become sagas, to use the Nordic label, and these combine to establish a unique history. Gradually the organization gets infused with value, to use Philip Selznick’s celebrated expression, to become what he called an institution, a system with a life of its own, having “acquire[d] a self, a distinct identity.”94

Stage 3: Reinforcing of the culture through identifications and socialization. People joining such an organization do not enter a random collection of individuals, but a living system, with its traditions and stories. To remain, they must come to identify with all this—become loyal members. Such organizations use interpersonal processes of socialization, or indoctrination, to institutionalize the commitment of its new members, as well as to reinforce that of the existing ones— for example, with social events of various kinds.

This is how a compelling culture is built—slowly, patiently. Once done, however, it can be difficult to change. But not to kill. Just go back to those “Five Easy Steps to Fix Your Organization” (in Chapter 8), each anathema to compelling culture.

Compelling Cultures in the Four Forms

A compelling culture can infuse any of the four forms, although it comes more readily to some than to others. Many Personal Enterprises fit Stage 1 rather well and so can be on their way to compelling cultures. An entrepreneur pursues a unique vision, which attracts people whom he or she sees as family, and so goes to great lengths to avoid laying them off in a crisis. Of course, once that founder goes, all this can come to an abrupt end.

Programmed Machines tend to be quite the opposite. Standards and systems, rules and measures hardly encourage people to pull together with conviction. Yet compelling cultures can sometimes be found here, too, in what can be called a snappy bureaucracy. There is spirit in its flesh, energy in its bones. Colin Hales has called this “bureaucracy-lite, not a radical shift to network organization but more limited change to a different form of bureaucracy in which hierarchy and rules have been retained but in an attenuated and sharper form.”95

In the Professional Assembly, the identifications tend to be individual and professional more than organizational. But given the missions of some of these assemblies—treating the ill, educating children— compelling cultures are not uncommon. In the Project Pioneer, there is more reason to expect compelling culture, thanks to the collaborative spirit that can exist in its teams. The decentralization of authority can help too, but this also allows people to speak their minds which can, as in the Professional Assembly, beget conflict.

The Intrusion of Conflict (Pulling Apart)

“Jobs fall into two classes, My Jobs and Your Jobs. My Jobs are public-spirited proposals, which happen (much to my regret) to involve the advancement of a personal friend, or (still more to my regret) of myself. Your Jobs are insidious intrigues for the advancement of yourself and your friends, speciously disguised as public-spirited proposals.”96

My Oxford dictionary defines conflict as “serious disagreement” and politics as “activities concerned with gaining or using power within an organization or group.” These two terms go together: disagreements arise when different actors try to gain or use power. Hence both will be used here.

Every organization experiences conflict, more or less, even if this is just some clash of personalities. Usually this is limited so that people can get on with things, but not always. Buy a condo and attend the owners’ meetings. One group may be determined to spruce up the place to increase its market value while another may be insistent on minimizing the fees. They may simply argue, but in some condos, this becomes cold war.

If a compelling culture pulls people together in an organization (centripetal), then the clashes of conflict pull them apart (centrifugal). Indeed, conflict itself can take a compelling culture apart, just as a compelling culture can bring conflicting parties together. This is a bit like that game where scissors cut paper, rocks crush scissors, and paper covers rocks.

For people trying to get things done in an organization, conflict and politics can feel intrusive. After all, if organizing is about attaining order, conflict is disorderly. But in the larger scheme of things, conflict is as natural as culture. Once again, even bees do it (see box).

Like bees, we are naturally collaborative creatures who can be highly competitive. Our cultures pull us together and our conflicts pull us apart. When we disagree, we might “play politics,” meaning acting underhandedly, outside the formal structure. If this sounds like some sort of game, it can, in fact, be seen as a whole set of them, some of which challenge the legitimate power of authority, expertise, culture, or else break down formal structure, while others use some legitimate kind of power in illegitimate ways.

Political Games in Organizations

Here are thirteen of the most common political games played in organizations.98

• The insurgency game is usually played to resist authority in an organization, although it can also be used to resist expertise or established culture, also to effect change. And so it tends to be played by people in weaker positions who feel the full weight of some form of legitimate power.

• The counterinsurgency game is played by those with legitimate power who fight back insurgencies with political actions, or legitimate actions used politically (as in the use of excommunication in a church to punish a dissenter).

• The sponsorship game is played by using someone in a more senior position to build a power base: an individual attaches him-or herself to a person with more status, professing loyalty in return for influence.

• The alliance-building game is played among peers, often line managers, sometimes staff experts, who negotiate implicit contracts of support for each other to advance their interests in the organization.

• The empire-building game is played especially by line managers, to build power bases, not cooperatively but personally, by maneuvering to enlarge their units.

• The budgeting game is played overtly and with rather clearly defined rules, to increase budgets. It is similar to the last game but is less divisive, since the prize is resources, not people. A common version of this game is to spend remaining funds on something not particularly necessary before they run out.

• The expertise game flaunts or feigns expertise. True experts flaunt the uniqueness and irreplaceability of their skills and knowledge, also resist having their skills programmed by keeping their knowledge to themselves. Nonexperts feign expertise, or else try to have their work viewed as expert, ideally to have it declared professional so that they can control it.

• The lording game is played by lording legitimate power over those without it, or with less of it. A manager lords formal authority over a member of his or her unit; a civil servant lords control of the rules over a citizen; an expert lords his or her technical skills over the unskilled.

• The line versus staff game, of sibling-type rivalry, is played, not just to enhance personal power, but also to defeat rivals. It pits line managers with formal authority against staff advisers with specialized expertise, each prepared to exploit legitimate power illegitimately.

• The rival camps game is also played to defeat rivals. Two camps form in the organization and challenge each other. This can occur when alliance-or empire-building games end with two major power blocs that fight it out. Being zero-sum, this can be the most divisive game of all, akin to civil war. The conflict can be between units (for example, engineering versus architecture on a building site), between rival personalities (two executives vying to become CEO), even between two competing missions (as in prisons split between staff favoring custody and rehabilitation).

• The strategic candidate game is played by individuals or groups determined to promote a favored strategic option through the use of political means. Possible players of this game can include analysts, operators, and managers, even chief executives. (A number of the other games are played within this one.)

• The whistle blowing game, typically brief and simple, is also played to effect change in the organization, but of a different kind. An insider, usually not senior, uses restricted information to blow the whistle on some questionable or illegal behavior within the organization, by informing influential outsiders, or some senior insider, even a member of the board of directors. This game is often stymied by the guilty party, in a version of the counterinsurgency game.

• The subversion game is played for the highest stakes of all, not just to effect simple change or resist legitimate authority, but to throw the latter into question, perhaps even overthrow it. A small group of determined insiders, sometimes close but not quite at the center of power, seeks to alter the organization’s strategy, change its culture, or replace its leadership.

Some of these political games, such as sponsorship, lording, budgeting, and line versus staff, while themselves technically illegitimate, coexist with legitimate systems of influence; indeed, they could not exist without them. Other political games, such as insurgency and subversion, arise in the presence of legitimate power but are antagonistic to it.

Conflict in the Four Forms

The least amount of conflict might be expected in the Personal Enterprise, where a chief who is in close touch with everything can snuff it out quickly. Of course, if the chief falters, look for the insurgency or subversion game to force him or her out. But even that can be tricky. Witness all those autocrats who have hung on to power long after their time was due, thanks to their control of the levers of power—the armed forces for dictators, sycophants for company chiefs.

In the Programmed Machine, the sharp divisions of labor, and resulting silos and slabs, encourage parochialism that gives rise to political games intended to build narrow bases of power—empire building, budgeting, sponsorship, line versus staff. And while the tight controls may discourage the more antagonistic political games, look especially for the lording game, sometimes also insurgency, subversion, and whistle blowing.

The professional and project organizations have weaker systems of authority but stronger systems of expertise, the powers of which are widely dispersed. Thus, look for considerable political activity here, especially the games that pit groups of insiders against each other, whether to enhance narrow bases of power or just to battle with rivals. Professional Assemblies are especially inclined to split into rival camps on ideological grounds, while the strategic candidates game can be common in the Project Pioneer.

Constructive Conflict

Little space need be devoted to the divisive and costly role of conflict in organizations: we know how much useful energy can be wasted in playing these political games. What does deserve space, however, because it is less widely appreciated, is how conflict and especially politics can be constructive.

In general, politics can be necessary to correct certain deficiencies in an organization’s legitimate systems of influence. Put differently, politics, whose means are (by definition) illegitimate, can be used to pursue ends that are legitimate—as when a whistleblower reveals the abusive behavior of a boss. We can elaborate on this in two specific points.

First, politics as a system of influence can act in a Darwinian way to ensure that the strongest members of an organization are brought into positions of leadership. Because authority favors a single chain of command, weak leaders can suppress strong subordinates. Politics, on the other hand, can provide alternate channels of communication and promotion, as when the sponsorship game enables someone to leap over a weak boss. Moreover, since dealing with conflict is a key part of the manager’s job, the political games can demonstrate a person’s potential for leadership. The second-string players may suffice for the scrimmages, but better to have the best meeting the competition. Political games not only suggest who these players are, but also help to remove their weaker rivals from contention.

Second, politics can promote different sides of an issue when the legitimate systems of influence promote only one. It can thus force an organization to face changes that have been resisted by its vested interests—the whistle-blowing game being a clear use of this. The system of authority, by aggregating information up the hierarchy, tends to advance a single point of view, often the one already known to be favored by the people in authority. The system of expertise can concentrate power in the hands of established experts, with their entrenched paradigms and protocols, while a compelling culture is rooted in firmly established beliefs. In the face of all these obstacles, politics can work as an “invisible hand”—more to the point, an underhand—to promote necessary change, through such games as strategic candidates, whistle blowing, and subversion. (Other benefits of politics will be discussed in Chapter 16, about the Political Arena, where politics engulf an organization.)

Obviously, political confrontation does not always correct a bad situation. Sometimes it exacerbates it, the solution proving worse than the problem. Moreover, some political challenges are arbitrary, or neutral: an influencer, for example, simply wants a new deal. In these cases, we cannot call politics constructive or destructive, although the period during which it endures can be called dysfunctional, since it uses resources that could have been doing other things. Hence the sooner the politics abate, the better.

Culture and Conflict

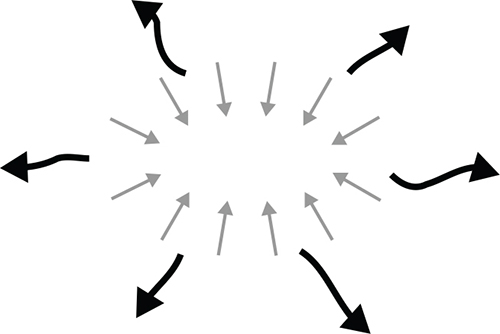

Culture and conflict coexist in organizations, sometimes to challenge each other—pulling together versus pulling apart—but also to keep each other in check. As shown in Figures 13.2a and b, a culture of inclusiveness can constrain the intrusiveness of conflict, just as the intrusiveness of conflict can loosen a culture that has become too inclusive.

FIGURE 13.2a Culture to Contain Conflict

Again, the arrows can tell the story. As various actors pursue their self-interest, the centrifugal force of conflict that could explode an organization can be restrained by the centripetal force of culture. Consider, for example, those Project Pioneers whose experts challenge each other internally yet present a united front externally once they have made their decisions. Likewise, a culture of overworked beliefs that is imploding can be pulled open by the explosive force of conflict. Hence the dynamic balance necessary in organizations can be maintained by the tension between culture and conflict.

FIGURE 13.2b Conflict to Open Culture