Focus Groups

Introduction

A focus group is an interview where five to ten (ideally six to eight) people are brought together to discuss their experiences or opinions around topics introduced by a skilled moderator who facilitates an open, nonjudgmental atmosphere. The session typically lasts one to two hours and is good for quickly understanding user perception about a particular topic or concept. Focus groups are used in a variety of settings, including social science research (since the 1930s) and marketing research. In our experience, the focus group is a valuable methodology when done correctly. Key benefits of focus groups are that the group dynamic brings up topics you may never have thought to ask about, and the synergy of a group discussion can stimulate new ideas or encourage participants to talk about things they would not have thought about if interviewed alone. Focus group participants are often more willing and able to discuss their experiences candidly and use their preferred style of language with a group of peers than individuals with an interviewer. On the other hand, a drawback of the focus group method is that participants may be more susceptible to social influence and acquiesce to particularly influential group members (Schindler, 1992).

In this chapter, we present a common method for conducting a focus group, as well as several modifications (refer “Modifications” section, page 353). Finally, we discuss how to present the data, along with some of our lessons learned. A case study by Peter McNally is provided at the end to demonstrate an application of this method.

Preparing to Conduct a Focus Group

Preparing to conduct a focus group study involves generating and refining the questions you will ask the group, determining the characteristics of the groups you are interested in studying, recruiting them to participate, inviting observers, and producing activity materials. Since a focus group is essentially a special case of an interview, we recommend you read Chapter 9, “Interviews,” prior to planning your focus group.

Create a Topic/Discussion Guide

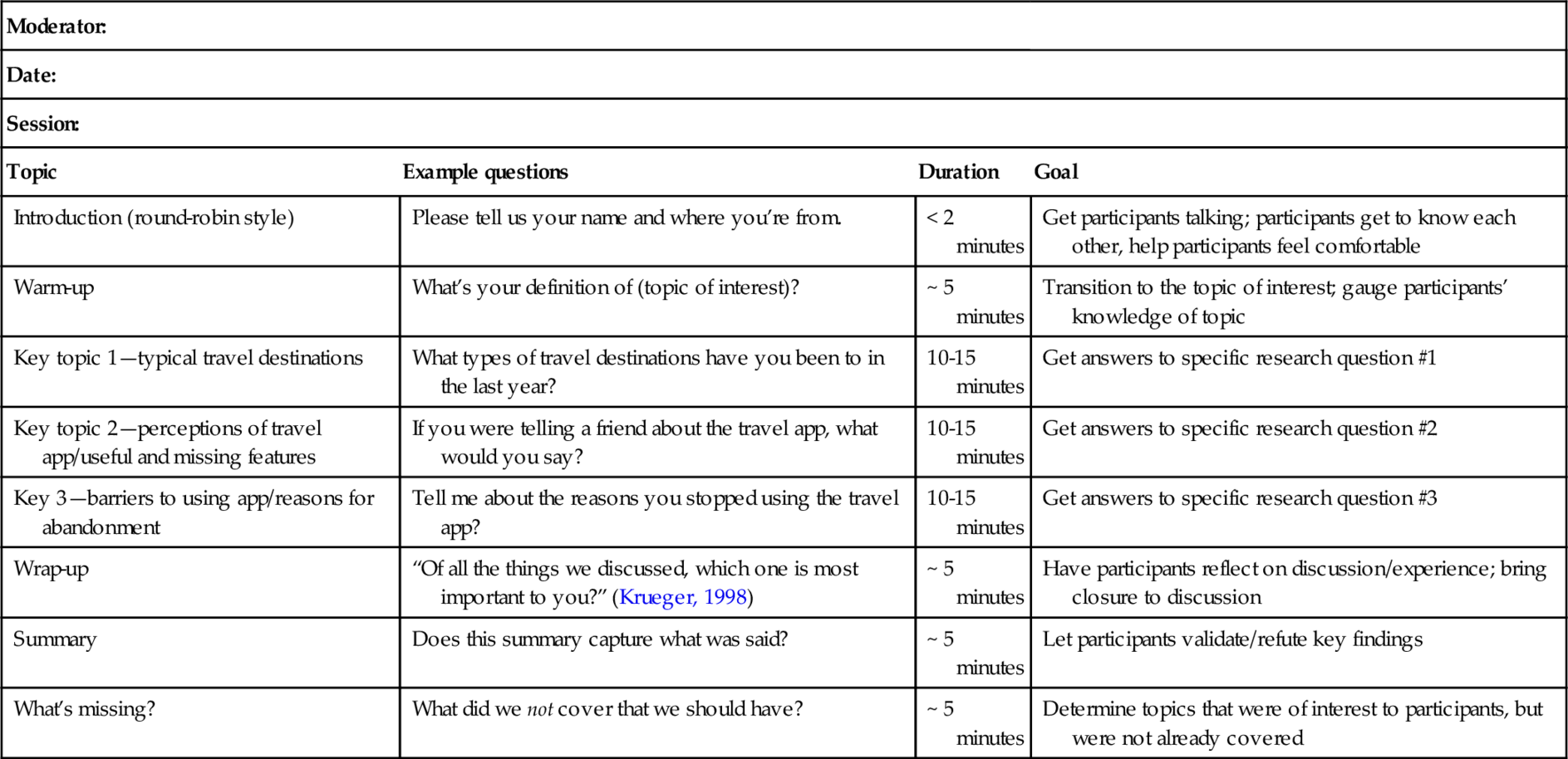

A topic or discussion guide for a focus group is a tool that helps the moderator keep a session on track (see Table 12.1 for a sample). It contains the key topics that must be covered and specific questions to be posed to the group. While it is a guide rather than a script, and therefore moderators are free to deviate from it to follow participant interest and conversations on other topics, it does help the moderator maintain consistency across groups.

Table 12.1

Sample discussion guide

| Moderator: | |||

| Date: | |||

| Session: | |||

| Topic | Example questions | Duration | Goal |

| Introduction (round-robin style) | Please tell us your name and where you’re from. | < 2 minutes | Get participants talking; participants get to know each other, help participants feel comfortable |

| Warm-up | What’s your definition of (topic of interest)? | ~ 5 minutes | Transition to the topic of interest; gauge participants’ knowledge of topic |

| Key topic 1—typical travel destinations | What types of travel destinations have you been to in the last year? | 10-15 minutes | Get answers to specific research question #1 |

| Key topic 2—perceptions of travel app/useful and missing features | If you were telling a friend about the travel app, what would you say? | 10-15 minutes | Get answers to specific research question #2 |

| Key 3—barriers to using app/reasons for abandonment | Tell me about the reasons you stopped using the travel app? | 10-15 minutes | Get answers to specific research question #3 |

| Wrap-up | “Of all the things we discussed, which one is most important to you?” (Krueger, 1998) | ~ 5 minutes | Have participants reflect on discussion/experience; bring closure to discussion |

| Summary | Does this summary capture what was said? | ~ 5 minutes | Let participants validate/refute key findings |

| What’s missing? | What did we not cover that we should have? | ~ 5 minutes | Determine topics that were of interest to participants, but were not already covered |

To create a discussion guide, you will need to identify the research questions you want to answer; generate, refine, and limit the topics and questions to be discussed; and finally, test the specific wording for each question.

Identify the Questions You Wish to Answer

By this point, you will already have a general idea of your research questions and have determined that a focus group is the most appropriate method for answering that question. You may still want to have a brainstorming session with all of your stakeholders (members of the product team, the UX group, marketing) to hone in on the most important questions to answer in your activity. You will likely end up with questions that are out of the scope of the proposed activity or questions that are best answered by other activities (e.g., behavioral questions). You may also end up with more questions than you could possibly cover in a single focus group session. If this is the case, you will either need to conduct multiple sessions or trim down the number of questions to fit into a single session.

Writing the Focus Group Questions

Focus groups are particularly well suited to answering questions that explore attitudes, feelings, and beliefs about a topic, elicit concerns, answer a “why” question about quantitative or behavioral data, gather the local vocabulary used to talk about a topic, generate new ideas, and require answers from groups, rather than individuals. Questions in a focus group should be open-ended, worded clearly, impartial (e.g., not leading), and actually ask what you intended to ask.

As you can see in Table 12.1 (also see Table 9.3 on page 226), we list six types of questions: introduction, warm-up, key, wrap-up, summary and what’s missing? Key questions are where you obtain the bulk of the information you will need to answer your research question.

Below, we list some types of questions that are suitable models of key questions:

■ Review a user’s “typical” day or the user’s most recent day (e.g., at work, at home, depending on the context of interest).

■ List questions. For example, list the tasks that users do and how they do them.

■ The domain in general (e.g., terminology, standard procedures, industry guidelines).

■ User’s likes and dislikes and/or advantages or disadvantages.

■ User’s desired outcomes or goals.

■ User’s reactions, opinions, concerns, or attitudes toward a new product/concept.

■ Desired outcomes for new products or features.

Krueger (1998) listed question types that are good for focus groups:

■ Create an analogy

■ Use fantasy and daydream

■ Use personification

Asking participants to discuss a “typical” day can give you a high-level overview of participants’ perceptions about the way they work or activities they may do in general. Asking participants to tell you about their most recent day in a context (e.g., at work) gives you specific examples about tasks they have recently done. You can also understand how certain tasks are done at a high level, the challenges they face, and the things they enjoy. Asking participants to think back to a specific example is preferable to thinking about the future.

Similarly, you should be careful to avoid asking “why” questions. Why questions may encourage participants to generate a cause-effect relationship about a topic that does not exist and may make participants feel worried that they will have to justify their responses. Instead, choose “how” questions (Krueger, 1998).

Focus groups also offer the opportunity to learn about local terminology, guidelines, and industry practices. Participants can additionally describe desired outcomes in their activities or goals they want to achieve. Finally, you can gauge user reaction to concepts and brainstorm ideas for new products or features.

We strongly recommend reviewing the advice given in Chapter 9 for additional guidance in developing key questions (see “Write the Questions” section, page 225).

Probes, Prompts, Pauses, and Checks

Probes, prompts, pauses, and checks are strategies to get participants to talk more about a topic of interest. Use one of these when you want participants to talk more about something you are interested in. We find the following probes particularly useful:

![]() Could you talk a little more about that (give me a little bit more detail)?

Could you talk a little more about that (give me a little bit more detail)?

![]() Could you tell me what you mean by that?

Could you tell me what you mean by that?

![]() I’m not sure I understand.

I’m not sure I understand.

![]() Who else has an idea?

Who else has an idea?

![]() Are there other ways to look at this?

Are there other ways to look at this?

![]() Could you give me an example?

Could you give me an example?

■ Prompts

![]() Say “uh huh” and/or shake your head to encourage the participant to continue talking. Be careful not to provide any negative feedback that could be interpreted as you disagreeing with what a participant is saying.

Say “uh huh” and/or shake your head to encourage the participant to continue talking. Be careful not to provide any negative feedback that could be interpreted as you disagreeing with what a participant is saying.

![]() Repeat the participant’s question.

Repeat the participant’s question.

![]() Repeat what the participant said in question format.

Repeat what the participant said in question format.

■ Pauses

![]() Be quiet—when you offer space to participants to speak, often they will.

Be quiet—when you offer space to participants to speak, often they will.

■ Checks

![]() So, if I understand correctly … (summarize) …

So, if I understand correctly … (summarize) …

Question Types to Avoid

Sensitive or Personal Topics

Do not discuss extremely sensitive or personal topics like politics, sex, or morals in a focus group. These are topics that are sometimes uncomfortable or cause heated discussion between friends and family. It is not appropriate for you to ask participants to discuss them in front of strangers and in a way that will be recorded. Plus, you may end up wasting everyone’s time if you ask but participants are not willing to tell.

Predictions

Studies have found that participants are not always good at predicting the features they would find useful in practice (Gray, Barfield, Haselkorn, Spyridakis, & Conquest, 1990; Karlin & Klemmer, 1989; Root & Draper, 1983). This is why we recommend against asking participants to “pretend” about things with which they have no experience. For example, it is completely appropriate for you to ask someone, “What is the biggest challenge you face in your job?” and then follow up the user’s response with, “What would make that part of your job easier to do?” You are not asking the participant to pretend—the participant does that job and may encounter that challenge every day. You can be sure that the participant has thought on many occasions about ways the challenge could or should be addressed. Going back to our travel example in earlier chapters, a travel agent might say that her biggest challenge is when people call her to book a vacation but never have the information needed, like the maximum budget, the dates of travel, and desired destinations.

On the other hand, you should not ask the travel agent whether she would like using voice-activated input, if the agent has never seen or used such a system before. She may think the concept sounds really cool when you describe it, but once she begins using it at work, she hates it because everyone in the surrounding cubicles can hear every mistake she makes.

Test Your Topics/Questions

Before you use the topic/discussion guide in a focus group, it is important to pretest the topics and questions. Start by sending the questions out for review by the team. Say the questions out loud. Do they sound conversational when spoken? Ideally, you should have people from your target group review the questions and offer feedback. Will these questions elicit the type of information the team is looking for? Do they use local language? If not, you need to reword or create new questions.

Ordering Your Questions

Generally, questions should be ordered from general to specific. This order is beneficial for two reasons. First, the flow is natural for participants. As participants warm up to a topic and other participants bring up related topics, they tend to remember more details. As the focus group progresses, participants also become more comfortable with the moderator and other participants and are willing to reveal more. Second, conversations naturally flow from the general to the more specific. Ideally, a focus group feels like a conversation with one topic leading naturally to the next. In a focus group that goes really well, the participant, rather than the moderator, brings up the next topic on the discussion guide, without having ever seen it.

Players in Your Activity

Of course, you will need representative participants to take part in your session, but there are also three additional roles that need to be filled to conduct a successful focus group: moderator, notetaker, and videographer.

Participants

Because focus groups are a group activity, in addition to considering who your participants should be, you also have to consider how many you will interview per group and how to form the groups.

Number of Participants

Since the group dynamic is an important component to this method, we recommend six to eight participants per session; however, groups as small as four can still provide valuable information (Krueger & Casey, 2000 pp. 73-74 suggest a range of 4-12 per group). Groups with more than ten participants can be difficult to manage, and with a large group, it is unlikely that everyone will have an opportunity to speak. It may seem like two additional participants will not make a big difference, but when you are trying to get multiple perspectives to multiple questions, it will.

Number of Groups

The recommended number of groups per participant type is three to four (Krueger & Casey, 2000, pp. 26-27). If you are restricted on the number of participants you can recruit, then opt to run multiple smaller groups rather than one large group. For example, run two groups with five participants each rather than one group with ten participants. This is because group dynamics can vary. You do not want one dominating participant to influence all of the participants in the session. In addition, you may learn information in one focus group that you never thought about and would like the opportunity to develop new questions for a second focus group. If you put all your participants in one basket, you lose the opportunity to revise your questions. Of course, if you change your questions between sessions, you cannot compare the answers across groups, but you do have the opportunity to cover more ground.

Participant Mix

Participants in a single focus group are typically similar in some way that is relevant to your research question. For example, if you were interested in getting input from both novice and expert users, you might group participants into these separate groups for sessions. Speaking with especially effective or expert users can provide a wealth of ideas since these “lead” users can often be a source of innovation. However, you should also recruit novice and average users since expert users may request features or services that are too sophisticated from the majority of the user population. By speaking with each user type individually, you can quickly understand the needs and issues for a broad spectrum of your population.

Some user types should not be placed together because they may negatively influence comfort and disclosure. For example, managers and their direct reports should never be placed in the same group because the direct reports may not be honest or may defer to their managers. Managers may even feel it necessary to “take control” of the session and play a more dominant or expert role in the activity to save face in front of their employees. The issues are similar when you mix user types of different levels within a hierarchy, even if one does not report directly to the other (e.g., doctor and nurse). Refer to “Lessons Learned” section on page 368 for a discussion of how mixing user types of different levels in a hierarchy can cause real problems.

The Moderator

One moderator per session should facilitate the activity (see “Conducting a Focus Group” section on page 351 as well as “Moderating Your Activity” section on page 165 in Chapter 7 for the details of being an effective moderator). The moderator’s job is to elicit meaningful responses from the group, manage the group dynamics (e.g., draw out quiet participants), examine each answer to ensure he or she understands what the participant is really saying, and then paraphrase the response to make sure the intent of the statement is captured. Finally, the moderator needs to know when to let a discussion go off the “planned path” into valuable areas of discovery and when to bring a fruitless discussion back on track.

To do all this effectively, the moderator needs to have sufficient domain knowledge to know which discussions are adding value and which are sapping valuable time. He or she also needs to know what follow-up questions to ask on-the-fly to get the details the team needs to make product decisions (see “ Lessons Learned” section, page 368). Finally, the moderator should make participants feel at ease and create an atmosphere where participants feel free to express diverse opinions. Moderators who adopt a nonjudgmental, open, encouraging, and respectful mindset will be particularly successful at putting participants at ease. It is also important that they encourage all participants to adopt this attitude as well. Participants should not critique one another’s ideas.

If you have never run a focus group before, we recommend you gain experience by participating in (not moderating) several different focus groups. You can go to online community boards or search job listings for companies in your area that are looking for focus group participants. Also, observe different moderators in action to learn what worked and what did not. You may also identify a certain style that you would like to emulate. Once you have been a participant and observed other moderators, it is essential that you practice moderating a focus group rather than just jumping in feet first. You do not want to learn “on the job” when expensive data collection is at stake.

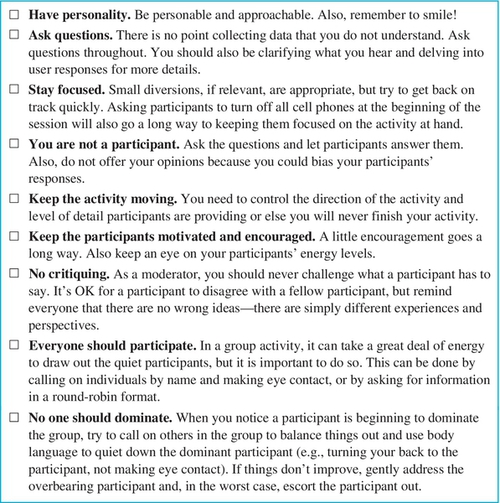

Figure 12.1 is a moderator’s checklist. For a detailed discussion of the art of moderating, refer to “Moderating Your Activity” section on page 165 in Chapter 7.

The Notetaker

A notetaker is needed to help the moderator. The moderator has a big job and should not be worried about taking detailed notes. The sole job of the notetaker is to write down notes from the session. It is important for the notetaker to have domain knowledge so that he or she knows what points are important to capture and what comments can be left out, as well as to ensure that the notes make sense. (See “Lessons Learned” section on page 368 to read more about the importance of domain knowledge.) You will find a detailed discussion of notetaking tips and strategies in Chapter 7 (see “Recording and Notetaking” section, page 171).

The notes can be displayed for the group (including the moderator) to see. This can be done on a laptop and projecting the image or by writing the notes on flip charts at the front of the room. Obviously, reading someone’s handwriting is not an issue when using a laptop, but if your notetaker is not a fast or good typist, you may want to go with the handwritten notes. An obvious advantage of typing the notes during the session is that you can send out the notes to stakeholders immediately following the session.

Taking notes for the group to see has a few advantages and disadvantages. One advantage is that it can help the participants to avoid repeating the same information, and it shows the participants that their comments have been captured (otherwise, participants may ramble on to be sure you captured what was said). If the notetaker captured a comment incorrectly, the participant can correct him or her immediately. Finally, the moderator can refer back to the notes during the session to follow up on a particular comment or to direct the group to a different line of discussion.

One disadvantage to having the notes displayed for all to see is that you may not be able to use a lot of shorthand because the participants will not understand it. Additionally, the notetaker should not include design ideas or notes about the participants, comments, or session for all to see.

Whether or not the notes are being displayed to the group, the big benefit to having a notetaker is to avoid the need to watch the entire focus group on tape for later data analysis. As soon as the session is over, you have data at hand to begin analyzing. If there are areas where the moderator feels that the notes do not make sense, he or she can go back and watch just that portion of the session. This cuts down significantly on the time it takes to analyze the data. Finally, the notetaker can help you analyze your data. Since the notetaker was there for the entire session, he or she understands the data as well as you, and it is always helpful to have an extra pair of eyes and a different perspective to analyze the data.

Some focus group moderators prefer to have their sessions transcribed by professionals. People working in highly regulated fields (e.g., the pharmaceutical industry regulated by the FDA) may be required to have precise documentation of any user research activity they conduct, since the information learned in such sessions provides data for making product design decisions. Transcribing focus group sessions is extremely time-consuming and expensive. It can take six hours to transcribe one hour of tape. If multiple voices are involved, such as in a focus group, it will likely take longer. Transcription services charge $1-$4 per minute of audio. Shorter turnaround time often costs even more.

The Videographer

Whenever possible, you will want a video recording of your session. This recording can be useful for your analysis and can be shared with stakeholders who may not be able to attend a live session. You will need someone to be responsible for recording. In most cases, this person simply needs to start and stop the recording and keep an eye out for any technical issues that arise. This task can be combined with notetaking. For more information on the benefits of video recording, refer to “Recording and Notetaking” section on page 171 in Chapter 7.

Inviting Observers

If you have the facilities to allow stakeholders to view these sessions, you will find it highly beneficial to get them involved (see Chapter 4, “Lab Layout” section, page 87). Stakeholders can learn a lot about what users’ like and dislike about the current product or a competitor’s product, the difficulties they encounter, what they want, and why they think they want it.

If you take a break during the session, you can ask the observers if they have any questions they would like answered or areas they want to delve into further. You should not promise you will be able to cover them, but if time and opportunity permit, it is good to have these additional questions available. If the questions the observers suggest are clearly biased or would derail the focus group, you can always state, “Those are questions that we might want to consider for another activity.”

Activity Materials

A basic focus group requires very few materials. Options include:

■ Laptop/computer or whiteboard or flip chart

■ Computer projector and screen (if using laptop/computer)

■ Blue or black markers (if using whiteboard or flip chart)

■ Materials for creativity exercises

■ Paper and pens for participants to take notes

■ Prototype or other artifact to stimulate discussion (optional)

■ Large room conducive for a group activity

■ Name tents or nametags

■ Recording equipment

We prefer to use a laptop and display each question using a projector (see Figure 12.2). This looks professional and the questions are easy to read. A whiteboard or flip chart will work just as well. Remember to write clearly and with large letters in blue or black marker.

It is valuable to provide paper and pens for the participants. If multiple people wish to speak at the same time, you may have to ask them to “hold their thoughts.” Sometimes, people forget what they wanted to say when they hear someone else speaking. It can be frustrating for both you and the participant if good ideas are lost. Allowing participants to jot a quick note on paper can help save those great ideas.

Finally, presenting a prototype, a competitor’s product, or a video (if appropriate) can help encourage discussion and focus thoughts. You do not want to bias participants’ answers, but it is often helpful to show examples of the product (yours or a competitor’s) during the discussion. Make sure that all participants can easily see whatever you are presenting.

Conducting a Focus Group

You are now prepared to conduct a focus group. In this section, we walk you through the steps to conduct your session.

Activity Timeline

The timeline in Table 12.2 covers in detail the sequence and timing of events to conduct a focus group. It is based on a one- to two-hour session and will obviously need to be adjusted for shorter or longer sessions. These are approximate times based on our personal experience and should be used only as a guide.

Table 12.2

Timeline of a focus group session

| Approximate duration | Procedure |

| 5 minutes | Welcome participants (introductions and forms) |

| 5 minutes | Creative exercise/participant introductions |

| 45-100 minutes | Discussion |

| 5 minutes | Wrap-up (thank participants and escort them out) |

Now that you know the steps involved in conducting a focus group at a high level, we will discuss each step in detail.

Welcome the Participants

This is the time during which you greet your participants, allow them to eat some snacks, ask them to fill out paperwork, and get them warmed up for your activity. It is helpful to begin with a creative exercise such as designing name tents. Alternatively, you can discuss likes and dislikes of the current system or a competitor’s product. The details of these stages are described in “Warm-Up Exercises” section on page 165 in Chapter 7.

Introduce the Activity and Discussion Rules

Once all forms are complete, introductions are made, and the participants are warmed up, the rules for discussion should be provided. The rules are simple: “All ideas are useful and please speak one at a time.” It is important to explain to participants that their individual experiences may be different and those differences should be expressed—but they should not critique each other’s ideas or perceptions. Write the rules “All ideas are correct” and “Please speak one at a time” on a flip chart and have it visible during the entire session. This will help tell participants that you are interested in everyone’s opinions and that they should be respectful of the thoughts and expressions of the other members of the group. If anyone breaks the rules, the moderator can point to it as a polite reminder. Now is also a good time to remind participants that you will be recording the activity and give them an idea of how long you expect the session to last.

The Focus Group Discussion

Participants should feel that the focus group session is free-flowing and relatively unstructured. You have your discussion/topic guide and possibly a list of questions to be covered during the session, but you may discover interesting insights by allowing a conversation to progress down an unexpected path. Group interaction is the key benefit of focus groups, so it is important to be open to new topics and allow the conversation to flow; otherwise, you may as well do a series of individual interviews. If your questions are presented on slides (see Figure 12.3), that does not mean you are locked into asking the questions in that order. If a topic comes up out of turn, feel free to go with the flow. Just make sure you come back to the other questions so all your questions are answered by the end of the session. Create a parking lot flip chart, if a topic comes up that is out of scope. You can capture it and indicate that you will get back to these after the session, if time permits.

Everyone Should Participate. No One Should Dominate

It is your job as moderator to engage all the participants in the discussion. This is typically done by containing any overbearing participants and drawing out quiet participants. It can take a great deal of energy to draw out the quiet members, but it is worth the effort to do so. If you have a focus group of ten people and only five are contributing, that essentially cuts your effective participant size in half. You must get everyone involved and the sooner you do this, the better. Call quiet members out by name and ask them their thoughts: “Jane, what do you usually do next?” If things do not improve, you could try moving toward a round-robin format (i.e., everyone participates in turn). If you start off doing a round-robin, you may not need to continue it for the whole activity; just a couple of turns may help people feel more comfortable about speaking up.

It can also take a great deal of skill to handle an overbearing participant who dominates the group and spoils the group dynamic. When you notice that a participant is beginning to dominate, call on others in the group to balance things out. Use body language to discourage the dominant user and encourage the quiet members. Turn your body or eyes away so that the dominant one cannot get your attention and focus fully on a quieter participant. If things do not improve, gently thank the overbearing person for earlier ideas and let him or her know that now, other participants need to contribute. If this does not work, you can ask participants to raise a hand before speaking and to have an assistant note any hand that goes up to make sure that everybody gets called on eventually.

If it is clear that the participant will not work with others, give the group a break. Take the dominant member to the side and remind him or her that this is a group activity and that everyone should participate equally. Alternatively, you can thank the user and provide a graceful exit. It is certainly the exception and would only be used as a last resort (e.g., if the participant is being rude or offensive), but it is good to have a plan of action in mind just in case.

We have noticed that highly trained or technical users tend to have more dominating personalities. If you will be conducting a group activity with highly skilled users, beef up your moderations skills by practicing with your colleagues. Consider having a colleague assist you, since two people correcting the overbearing participant may be more effective.

Modifications

Because focus groups have been in use for so many years, there are a plethora of different modifications that you can try. Many of them involve providing users with exposure to the product or concept under development in different ways so that users have some base of experience from which to draw.

Including Individual Activities

While the purpose of a focus group is to understand perspectives from a group, this does not preclude also collecting data from individuals. For example, you could ask participants to rank options individually or ask participants to vote for their preference. Rather than asking everyone to vote by raising their hand (and risk groupthink or evaluation apprehension), you can ask people to vote on paper. You can have the questions preprinted and distribute each question at the time you would like to vote. This prevents users from filling out all the questions in advance rather than paying attention to the group discussion. You may also choose to give a survey prior to or following a focus group in order to address questions that you do not have time to address in the focus group itself.

You may also ask closed-ended questions. These are questions that provide a limited set of responses for participants to choose from (e.g., yes/no; agree/disagree; option a, b, or c), rank a series of options, or vote for a preferred choice. You can also poll the participants (i.e., determine how many people agree with a statement). The benefit of collecting this type of data during a focus group rather than on a survey (where it is typically collected) is that you can ask individuals to discuss why they made the selection(s) they did. In fact, it is best to think about ratings and polls as providing an opportunity to have a discussion rather than as a quantitative measure of a preference or attitude. Live polling allows you to ask closed-ended questions and gather real-time results using text messaging, a smart phone app, or other handheld input device (e.g., “clicker”). Those results can then be displayed immediately to the group without the moderator having to tally results.

Task-Based Focus Groups

In task-based focus groups, participants are presented with a task (or scenario) and asked to complete it with a prototype or the actual product. If your product is a software or web application, this will obviously require several computers. After participants have completed their task(s), they are brought together to discuss their experiences.

It is best to give the participants the same set of core tasks, so they can share common experiences. For example, in one study, participants were asked to look up information in a user’s manual and describe how confident they were that the answer they gave was right (Hackos & Redish, 1998). Similar focus groups have been conducted for car owner’s manuals, appliance manuals, and telephone bills (Dumas & Redish, 1999). Keep in mind, however, that a focus group is not a substitute for a usability test.

Similarly, you can present participants with multiple activities or artifacts during a single focus group. Participants may start off with a brief group discussion, but then, they work individually for the majority of the session. Multiple facilitators are needed for this activity. Each facilitator works with a participant one-on-one and completes a different activity (e.g., brainstorming new ways of solving a problem, viewing a prototype). After all the participants have gone through all of the activities, the group reconvenes to discuss experiences. Ideally, all participants will have completed all of the activities.

An excellent example of this methodology began with each of five focus groups photographing participants holding phone handsets to assess gripping styles (Dolan, Wiklund, Logan, & Augaitis, 1995). Participants then rank-ordered six conventionally-designed handsets and six progressively-designed handsets according to several ergonomic and emotional attributes (after having experience with each). Finally, participants critiqued the handset designs according to personal preference, and each built a clay model of his or her ideal handset. By giving participants exposure to a wide range of experiences with the potential product or domain area, participants do not need to “imagine” what a product would be like. They can discuss their actual experiences with the product or domain and determine whether or not the product would support their desired outcomes or goals. The activities can also spark new ideas for you to draw upon.

The same type of questions can be asked in task-based and nontask-based focus groups. The benefit of task-based focus groups is that follow-up discussions are richer when participants have the opportunity to actually use the product than when they must simply imagine it or remember when they used it last. With this technique, participants can reference the tasks they just completed to provide concrete examples, or the tasks may trigger previous experiences with the product.

The cost of doing such a study is that you must have several sets of your product available so that participants can work with them simultaneously. You will also need several facilitators to help, and the prep time to develop such a focus group will be longer than for traditional focus groups, since you need to create the materials for several activities. It can also be more expensive because more materials are needed. However, the added benefit of giving participants something to experience and work with is worth the cost and should be done whenever possible!

Day-in-the-Life

You can create a “day-in-the-life” video to demonstrate how someone would use your product and then discuss participants’ impressions of what they have seen. Participants can get a better idea of what the product is really like without having to imagine it. This is perfect for situations where you cannot give participants direct exposure to the product or domain (e.g., because it would require significant training, there are safety issues, it would be financially infeasible).

It is important to show someone realistically using the product (warts and all!) since providing an idealized image will not result in valid user impressions. This allows users an opportunity to determine whether what they are seeing would address their desired outcomes. It takes additional time to create the video and may even require you to develop a prototype of the product to work with, if a real version does not exist. The benefit of getting all the participants on the same page and enabling them to share your vision is worth it!

Iterative Focus Groups

With iterative focus groups, you begin by presenting a prototype to participants and getting feedback from them. This can be specific design suggestions or just general impressions. Once the prototype is updated to reflect the feedback from users, the same participants are called back to participate in a second focus group. The new prototype is presented and additional feedback is collected. You could continue this iterative process as long as participants return, until you feel comfortable with the design, or until you run out of money.

The benefit is that you can see whether you are on the right track and understand the participants’ requests. It also takes less time to recruit since you are not looking for new participants each time. On the other hand, this modification is useful only in cases where you have enough information to build a prototype and you have the time and resources to make regular changes and conduct additional focus groups. The downside is that it takes time and resources to make changes to a prototype and run additional sessions.

The Focus Troupe

The “focus troupe” is an interesting twist on the focus group (Sato & Salvador, 1999). Members of the UX or development group—or even the participants themselves—perform dramatic vignettes demonstrating the new product, feature, or concept in use (participants would follow a script). The play should demonstrate the implications, operations, and expectations of what the product would do. A discussion among the group is then initiated.

As with some of the modifications listed earlier, participants can gain experience with the product or domain and this will limit their need to “pretend.” They can think of concrete examples of “using” the product while they provide their reactions, opinions, and alternative suggestions. The additional cost of using this modification is the time it takes to write the script(s) and—if you use colleagues in your troupe—the additional people involved. However, if you are unable to create a working prototype, this is the next best option.

Online or Phone-Based Focus Groups

Smaller focus groups (i.e., six or fewer participants) can be conducted via video chat, using VoIP or over the phone. This is more convenient for participants, and you can recruit people from outside your geographic region. You can also save money because participants will often participate for less, since they do not have to leave the comfort of their home or office. However, you need a video-conferencing system or phone system that allows multiple people to call and clearly hear everyone speak.

There are several disadvantages to this modification. Social loafing (i.e., the tendency for individuals to reduce the effort they make toward some task when working together with others) is potentially high because participants are not held accountable by their peer group or the moderator if they do not contribute. A participant can surf the web or text without others seeing it. Doing a “round-robin” can help because everyone knows they will be called on to contribute to the question, so they are less likely to slack off. It is also helpful to ask all participants to say their name before responding. It will be more obvious if, during an hour-long focus group, you never hear Ritee announce his name. In that case, you call on Ritee directly to reply.

Another problem is that the moderator cannot read the body language of the participants. There is no way to know whether a participant is silent out of disagreement or boredom or because he or she has nothing to add. Queue jumping by overbearing participants can also be a problem. It is hard to know who is speaking (even if you ask people to announce themselves before they speak) or if someone wants to speak but cannot get a word in edgewise!

Figure 9.1 in the “Interviews” chapter on page 224 can help you further determine whether it is better to conduct the session in person or over the phone. Overall, we recommend computer-mediated groups when you have geographically diverse users, when you do not need to demonstrate a product, when you are tight on resources, and when you have a high-quality phone conferencing system available.

Brainstorming/Wants and Needs Analysis

A possible component of focus groups is brainstorming. A wants and needs (W&N) analysis is an extremely quick, and relatively inexpensive, brainstorming method to gather data about user needs from multiple users simultaneously. Brainstorming with users is the key component of the W&N analysis, but the analysis has an added benefit compared to brainstorming alone because it incorporates a prioritization step that allows you to identify the most important wants and needs from the entire pool of ideas that were generated.

This method is ideal when you are trying to scope the features or information that will be included in the next (or first) release of the product. It enables you to find out what your users want and need in your product. Finally, by adding features based on the prioritized list, product teams can prevent feature creep (i.e., the tendency to add in more and more features over time).

Your goal is to gain an understanding of what the users want and need in the product. Rather than allowing the participants to brainstorm about anything they would like, it is more effective to ask the question so that it targets content, tasks, or characteristics of your product. Based on this assumption, the W&N question can be asked in three different forms:

■ Information. You can ask a question that will tell you the information that users want and need to be found in, or provided by, the system. A typical content question might be: “What kind of information do you need from an ideal online travel app?” You might receive answers, such as hotels available in a given area, hotel prices, airline departure and arrival time, etc.

■ Task. You can ask a question that will tell you about the types of activities or actions that users expect to be performed or supported by the system. A typical task-based question might be: “What tasks would you like to perform with an ideal hotel reservation system?” Some of the answers you receive might be as follows: book a hotel, compare accommodations between hotels, create a travel profile, etc.

■ Characteristic. You can ask questions that will provide you with traits users want or need the system to have. For example, “What are the characteristics of an ideal system that lets you book travel online?” Some responses you might receive are “reliable,” “fast,” and “secure.”

The question you ask should mention “the ideal system” because you do not want participants to be limited by what they think technology can do. You want participants to think about “blue sky.”

However, one should be aware of the following:

■ People do not always know what they really would like and are not good at estimating how much they will like a single option.

■ There are always variables that people do not take into consideration.

■ What people say they do and what they actually do may be different.

That is why the questions you ask users should not be for:

■ Ill-defined problems (e.g., problems that are broad or unclear)

■ Complex emotions (e.g., hatred)

■ Things with which users have no experience

In the W&N analysis, you are asking users what they want or need, but the questions are well defined and about things users already have some amount of experience with.

It is critical to note that a W&N analysis is only the beginning, not the end. It should be used as a jumping-off point and not as your sole source of information.

Introduce the Activity and Brainstorming Rules

After a warm-up, we jump into a brief overview of the goal and procedure of the activity. We say something along these lines:

We are currently designing < product description> and we need to understand what < information, tasks, or characteristics> you want and need in this product. This will help us make sure that the product is designed to meet your wants and needs. This session will have two parts. In the first part, we will brainstorm < information, tasks, or characteristics> of an ideal system; and then in the second part of the activity, we will have you individually prioritize the items that you have brainstormed.

After the brief overview, the rules the participants must follow during the brainstorming session are then presented. We always write these on a flip chart and have them visible during the entire session. If anyone breaks one of the rules, the moderator can point to the rule as a polite reminder.

Rule 1: Ideal System, No Wrong Answers

In the brainstorming phase, we want everyone thinking of an ideal system. Sometimes, users do not know what is possible. Encourage them to be creative and remind them that we are talking about the ideal. Because this is the ideal system, all ideas are correct. Something may be ideal for some users and not for others—and that is OK. Do not worry about unrealistic ideas, as they will be weeded out in the prioritization phase.

Rule 2: No Designing

Some users are steeped in the latest technology and will want to spend the entire session designing the perfect product. Users do not make good graphical or navigational designers, so do not ask them to design.

Rule 3: Moderator Checks for Duplicates

Another job of the moderator is to check for duplicates. Sometimes, users forget that someone made the exact same suggestion earlier. When you point it out to them, users will respond that they had forgotten about it or not seen it. However, there are times when the user is not asking for the exact same thing; it just sounds like it. This is where you must probe for more details and learn how these two suggestions are different from each other so that you can capture what the user is really asking for. It is important to mention this to the participants as a rule, so they do not think you are challenging their idea—you are simply trying to understand how it differs from another idea.

Rule 4: Notetaker Writes Down Only What the Moderator Paraphrases

This rule is important to set the participants’ expectations. Participants may not understand why the notetaker is not writing down verbatim everything they are saying. It is not because the notetaker is rude and does not care what the participants are saying. It is because the moderator must understand what the participants really want with each suggestion. What the participant initially says may not be what he or she really wants. The notetaker needs to give the moderator time to drill down and get at what the participant is asking for before committing it to paper. Once participants understand this, they will understand that the notetaker is not being rude but is simply waiting for “the final answer.”

Brainstorm

After about 40 minutes or so of brainstorming, you will notice that the number and quality of ideas tend to decrease. When you ask for additional suggestions, you will probably be met with blank stares. At this point, ask everyone to read through the list of ideas and make sure none are missing. If you are still met with silence, the generation phase is over. It is now time for the prioritization phase.

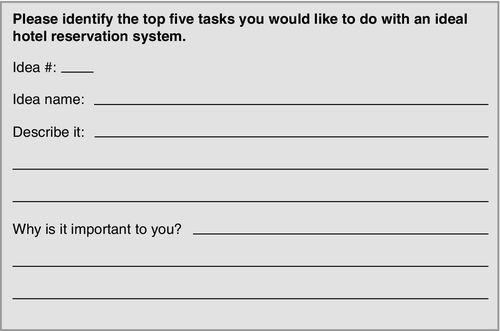

Prioritization

In the prioritization phase, users spend about 15 minutes picking the most desired items from the pool of brainstormed ideas. They are asked: “If you could have only five items from the brainstormed list, what items would you pick?” We ask for five choices because we have found that this will elicit the “cream of the crop.” We also like asking for five because we often ask two W&N questions during a two-hour session. For example, during the first hour, we may ask about information desired in an ideal system, and in the second hour, we may ask about the tasks desired in that same ideal system. By asking for the top five at the end of each brainstorming portion of the session, it keeps the evening to two hours and it does not exhaust the participants. Choosing the top selections is quite an exhausting procedure for the participants, so the more choices you ask for, the more time and effort it takes.

Participants fill in their answers in a “Top five booklet.” The booklet asks users to name the item they are choosing, describe it, and state why that item is so important to them (see Figure 12.4). We ask for this additional information to be sure that we are capturing what the users are really asking for. People may choose the same item from the brainstormed list but have completely different interpretations of these items. The descriptions and “why is it important” paragraph will help you detect these differences in the data analysis phase. A brief set of instructions is provided for users:

■ Write only one item per page. If more than one answer is provided per sheet, the second answer will be discarded.

■ Indicate the number of the item from the brainstorming flip chart.

■ The five are not ranked and are of equal weight.

■ No duplicates are allowed. If anyone votes for the same item more than once, the second vote will be discarded.

■ Provide a description of the item.

■ State why it is important to you.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Data analysis and interpretation of focus group data are similar to methods for other types of interview data. Therefore, refer to “Data Analysis and Interpretation” section on page 252 in Chapter 9 for additional information on how to analyze data.

Debrief

Ideally immediately following, but certainly within 24 hours of the focus group session, we recommend getting together with your notetaker (and any other team members who may have attended) to have a debriefing session. Review the questions asked and note the key points from the session. Were there any unexpected findings? What did each observer identify as the key takeaway from the session? Are there any trends that can be identified at this point? Fill in areas of the notes that may not be clear while everything is still fresh in your mind. You should also decide whether another session is necessary with the same user type. If so, determine if you would like to change the questions based on what you learned in the previous session.

Types of Focus Group Data

Focus group data consist primarily of notes from the session, audio recordings, and video recordings. Specifically, you may draw upon the following as you analyze the results:

■ Notes taken by the notetaker

■ Notes taken by observers (they can have different insights on the participants’ comments)

■ Notes taken during the debriefing session(s)

■ Audio/videotapes of the sessions

■ Transcripts of the sessions (if available)

■ Notes participants may have made during the sessions

Affinity Diagram

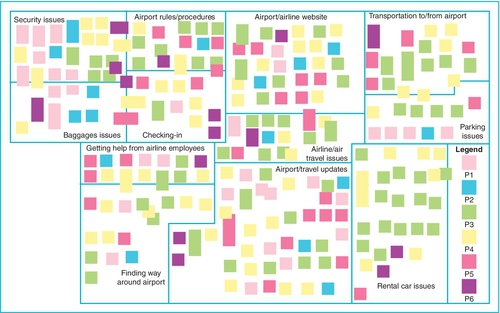

A Japanese anthropologist, Jiro Kawakita, developed a method of synthesizing large amounts of data into manageable chunks based on themes that emerge from the data itself. It is known as the “K-J method,” following the Japanese custom of placing the family name first. It has become one of the most widely used of the Japanese management and planning tools.

In the west, a very similar method known as “affinity diagramming” was developed based on the K-J method. An affinity diagram is a relatively quick and useful method for analyzing qualitative data, including open-ended participant responses from a focus group, as well as a diary study, interview study, or field study. It can also be used to group characteristics when building personas (Chapter 2, page 24) or to analyze findings from a usability test.

To create an affinity diagram, a researcher takes the data from each participant, pulls out key points (e.g., participant comments, observations, questions, design ideas) and writes each one individually on an index card or sticky note. The cards are then shuffled to avoid any preexisting order and each card/sticky note is placed on a wall or whiteboard. Similar findings or concepts are physically grouped together (on the wall or whiteboard), thus providing visual cues that allow the researcher(s) to identify themes or trends in the data. Figure 12.5 shows an large affinity diagraming process.

It is important to enter the analysis with an open mind and not preconceived categories within which that the data must fit. The structure and relationship will emerge from the data. Once the groups have emerged, you should label each group. What do these comments have in common? Why do they belong together?

When Should You Use an Affinity Diagram?

There are many situations when an affinity diagram is an appropriate and useful analysis method:

■ An affinity diagram is an excellent method for sharing the results of your study with stakeholders as the study progresses. They can look at the physical diagram to see evolving trends, as well as individual pieces of data. It also allows for quick data analysis once the study is complete (see step 7).

■ It can add structure to a large or complicated issue. You are able to break down a complicated issue into broader categories or more specific, focused categories.

■ It helps you to identify issues that affect multiple areas because those same issues belong in multiple groups. It can also help you identify areas where you are missing information and the scope of issues that need to be addressed.

■ When using an affinity diagram, you can see that the design/product ideas are based on direct user data. If you recommend solution A, you can point to a group of data points (each with an associated participant ID) that informed your recommendation.

■ Because individual issues, requests, or problems are grouped into higher-level themes, the team can respond on a broad scale rather than trying to address each one individually. This leads to a holistic rather than piecemeal solution.

■ It can help with innovation because you are not working from preconceived categories. New ideas emerge from the data.

■ By working as a team with the raw data, you can gain agreement on an issue. It can also help unify a team because the product development team can take part in the analysis, alongside the person who led the study.

Things to Consider When Using an Affinity Diagram

Using an affinity diagram requires one to enter with an open mind and be creative. Some people are uncomfortable with using the gut feeling and feel more comfortable adding in structure. This often results in an attempt to create categories a priori (i.e., before the sorting). That defeats the purpose of using an affinity diagram. Make sure your team members understand the purpose of affinity diagram and the benefits to its approach before the analysis begins.

Creating an Affinity Diagram

Below are the steps to create your own affinity diagram. If you have never used an affinity diagram before, the process may be slow at first. With each analysis session, the team will get faster.

Step 1: Find a space

You can create an affinity diagram on any wall or whiteboard in your office, a lab, or a conference room. Obviously, the amount of space needed depends on the amount of data you collected. Since you will likely work on it for the duration of your study, be sure the diagram is in a secure location where colleagues or cleaning staff will not undo your hard work.

Step 2: Assemble your team

Following each user research session, bring together the members of the team that took part in the session (e.g., moderator, notetaker, videographer). We strongly recommend updating your diagram after each session while the data are fresh in your mind; however, if this is not possible, then complete the diagram as soon as you have finished running all sessions for your activity.

As with the K-J method, affinity diagramming works best as a team approach. Your notetaker, videographer, and/or fellow field study investigator(s) should take part in this exercise. If a product team member was a part of the session, be sure to get him or her involved as well. Not only will that speed data analysis, but also the additional point of view is helpful. This is information that should be discussed and examined from multiple angles and used to pose hypotheses. Creativity should be encouraged, and there should be no criticism of people’s ideas or hypotheses.

Step 3: Create the cards

As a team, write key points of information from the data on index cards or sticky notes. Participant quotes, observations, hypothesis, questions, design ideas, pain points, etc., can all be included. You may choose to color-code your data by using different-colored cards or notes for each participant or for each type of data (e.g., quotes are green, hypotheses are blue, questions are pink). Depending on the length of your user research session and/or number of participants, you can generate 50-100 cards or more. You may want to indicate other things on the cards like the participant number, task, or site (in the case of a field study) associated with that data point.

Step 4: Sort the cards

Once all the cards are created for a session, the cards should be shuffled and divided among the members of the team. As each card is posted to the wall, the team member should say what is on the card out loud. When grouping similar cards, you do not have to state why you think those cards belong together. This can be a gut feeling. Do not try to label your categories early on. If you find an identical (or very similar) issue, problem, request, or quote, stack those cards on top of each other. You will be able to tell at a glance that the thicker stacks indicate recurring issues. You can also duplicate cards if you feel the item belongs in more than one group. To indicate that one issue or data point lives in multiple groups (and therefore affects multiple areas), you may want to create that duplicate issue on a different-colored index card or sticky note. This will help the duplicated issues stand out.

Step 5: Label the groups

After about three research sessions (e.g., interviews, focus groups, field study visits), you will see the categories emerging. At this point, you can begin to label each group with a tentative title or description.

Step 6: Regroup

As the sorting proceeds with data from more sessions, look for duplicate groups. If you have a lot of data, sometimes duplicate groups are created; combine these. Also, look for smaller groups. Do they belong with larger groups? They may not, but it is useful as you progress to look for higher-level groups emerging. Conversely, larger groups may need to be broken down into more meaningful subgroups.

Step 7: Walk through the diagram

After all research sessions are complete, the team should verbally walk through the diagram together. You may want to audio record this discussion or have a notetaker take notes, because the discussion will be useful when writing up the results of your study. The team should try once again to identify high-level groups and break larger groups into more meaningful subgroups. They should also make sure they are in agreement with descriptions for each group. Members are free to add cards with clarifying information, new insights, design ideas, and questions for further investigation.

Figure 12.6 shows an affinity diagram for a series of TravelMyWay focus groups conducted during a hypothetical mobile app field study. The intention of this figure is to give you a visual sense of what an affinity diagram might look like. As a result, we have not focused on the details of what could be written on each sticky note. The squares represent sticky notes with participant responses. Each participant is a different color. When the same participant made similar comments, the sticky notes were stacked on top of each other yielding rectangles, rather than squares. You will notice that some sticky notes cross the lines between categories. This means that the comment fell into more than one category and demonstrates related issues. The actual affinity diagram can be recreated in any drawing application so that the high-level groupings can be visually displayed in a report. More detail can be added than is shown here so that a poster can be created to display the results for all to see.

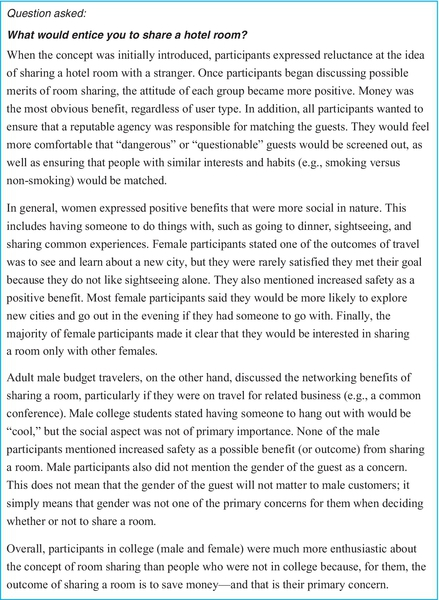

Communicating the Findings

Depending on the complexity of the data you collected, you can create a simple bullet list of information you learned during the focus group, a table comparing the answers between two or more user types, or a summary paragraph for each of the questions you asked users. Figure 12.7 is an example of a portion of a report.

Lessons Learned

Below are three lessons we have learned with regard to user composition, moderating, and notetaking for focus groups.

We advised earlier not to mix user types of different levels in a hierarchy. The first lesson learned demonstrates why. Also, as we indicated earlier, it is important for a moderator to have good domain knowledge to follow up on user comments, but it is also important for the notetaker. The moderator also needs to know how to handle difficult users, even to the point of removing a user to save the session.

Mixing User Types

A series of focus groups were conducted to learn about the use of “patient problem lists” (PPL) by nurses and physicians. The goal of a PPL is to bring a provider up to speed regarding a patient’s healthcare or medical history without having to review the patient’s entire chart. Both doctors and nurses use it, so the development team wanted to combine the two user types in the same session to reduce the number of sessions needed and to hear a discussion of their different perspectives. Because the type of work they do is different, and because the relationship between doctors and nurses can be antagonistic, we insisted on separating the two user types.

During one of the sessions with the physicians, the participants began insulting nurses over the way they maintain their paperwork and the notes they take. A development team member who happened to be a registered nurse was watching from another room and nearly leapt through the one-way mirror when she heard the physicians’ comments! Although both user types would have likely been on their best behavior if combined, we would not have gotten their honest opinions. The physicians’ comments may have seemed mean-spirited at the time of the session, but the point was clear that the notes the nurses take (and find valuable in their job) clearly do not meet the needs of the physicians. Everyone on the product development team realized that it was far safer and more enlightening to keep those user types separated in future user research activities, even if it meant running additional sessions.

Removing the Difficult Participant

During the same healthcare focus group discussed in the first lesson learned, we covered an amazing ten questions in each session. Each question was presented and then we completed a “round-robin” so that each participant had adequate time to contribute. After everyone had a chance to speak, people were free to add additional thoughts. This worked extremely well for nurses. Once we reviewed the ground rules for participation, we never had to refer to them again.

The physician sessions were more difficult to moderate. The participants did not stick to the “round-robin” format, interrupted each other frequently, disagreed with each other, and by the end of the session were speaking quite loudly in order to be easily heard over the others. The ground rules had to be referred to regularly. One outspoken physician in particular insulted the comments and ideas provided by another soft-spoken physician. Despite continued instructions of “everyone is right” and “do not critique the thoughts of others,” the domineering physician only got worse, and the soft-spoken physician stopped speaking altogether. The negative vibe rubbed off on the other participants and they all began criticizing each other’s ideas.

We realized that even with a great deal of experience moderating groups, it is easy to lose control of a session. Once you let one negative or overbearing participant take control of a group, the rest of the group will either behave similarly (e.g., insulting each other) or bow out of participating all together. Sometimes, humor and polite reminders will not work. It takes a strong hand to get a session back on track. In this case, it meant taking the participant to the side and asking him either to quit criticizing others or to leave altogether. This is uncomfortable to do; but for the well-being of your participants and for the sake of good data collection, it is critical that you intervene as soon as you realize the session is headed for a downward spiral.

For more tips and information on moderating activities, see “Moderating Your Activity” section on page 165 in Chapter 7.

Pulling It All Together

In this chapter, we have discussed what a focus group is, when you should conduct one, and things to be aware of. We also discussed how to prepare for and conduct a focus group, along with several modifications. In the following case study, Peter McNally discusses the use of focus groups for better user experience in the financial services industry.

Background

The financial services client approached the User Experience Center at Bentley University in 2013, seeking feedback on several design concepts related to retirement planning. Initially, we considered usability testing methods. We initially thought the client would be further along in the design process and be able to provide wireframes for their design concepts. When it became clear the client had mostly one graphic or high-level mock per design concept and their primary research goal was to determine if customers would be receptive to the concept, we recommended using the focus group method. Furthermore, since the client was looking for opinions on the usefulness of the concepts and not on the usability of the interaction, an individual feedback session, such as usability testing, would not be appropriate or cost-effective because it would take over a week to listen to the same number of participants. The project duration from kickoff meeting to final report presentation took about four weeks.

Initial Planning

We started with a kickoff meeting with the client project manager, the creative director, user experience designer, and several others from the client’s design agency to define the goals, the schedule, and the general approach for recruiting and concepts to be evaluated. The first step was participant recruiting.

Participant Recruiting

The client wanted to get feedback on five concepts across three different user groups: financial planners, consumers nearing retirement, and consumers early in their careers.

The same design concepts would be shown to all three groups. Ideally, it is best to hold at least two focus group sessions per user group in order to limit any bias from one session. However, in this case, since all three user groups would see the same design concepts and to complete the project within the client’s budget and schedule, we felt limiting the scope to one focus group session per user group would still provide valuable insights.

The recruiting process was similar to what we use for usability testing. We developed a screener for each focus group and hired a recruiting firm to recruit the participants. We recruited 10 participants for each focus group for two reasons: first, any more than this number makes it hard to facilitate the discussion, and second, if one or two participants canceled, we felt we could still have a good discussion with eight or nine participants.

Discussion Guide Development

With participant recruiting under way, we had several meetings with the client over two weeks to develop the discussion guide. The critical part of developing the discussion guide was to understand what the client wanted to get feedback on. We were given the design concepts from the client and their design agency. Word format was used initially to rough out the focus group flow. Eventually, the discussion guide was converted into three separate PowerPoint documents to facilitate presentation.

Housekeeping

During the first portion of the focus group, we introduced the moderator/participants, set ground rules and expectations, and obtained informed consent. Next, we did introductions. As part of the introduction process, I asked participants to tell me about a website or mobile app they currently use that is really good, fun, or entertaining. The site or app could be anything and did not have to be related to retirement planning. Responses varied from Twitter, to Instagram, to Words with Friends. The good thing about an icebreaker like this is that participants can piggyback on other comments, and before you know it, the group is sharing their experiences with you. Next, we explained how the focus group would be structured. Lastly, we spelled out specific ground rules to help the session run smoothly:

■ There are no right or wrong answers.

■ Honesty is appreciated.

■ Would like to hear from everyone.

■ I may cut you off politely for the sake of time!

■ All ideas are good. But we expect varied opinions. Feel free to agree and disagree with one another.

■ Provide constructive feedback.

Incorporating UX into the Focus Group

We showed several design concepts, spending about 15 minutes per concept. Each design concept consisted of one slide providing a high-level overview with a bulleted list of features and one or more slides with a high-level design or graphic giving a visual representation. However, rather than jumping straight into the features of the design concept, we provided a scenario setting the use case or problem. Providing a scenario gave the participants context and focused them on a goal or problem to be solved with the concept. For example, for a retirement savings calculator, we used the following scenario:

You need to save more for retirement, but you have a lot of other competing priorities, such as rent or the mortgage, car payments, and other expenses. You hear everyone saying you need to save more for retirement, but what is a realistic number for you?

When participants saw the design concepts, they referred back to the scenario during the discussion. In addition, for design concepts that showed any kind of user interface, we had the participants conduct a usability test either individually or as a group. For example, one design concept had two screens, the first displayed a main menu and the second screen displayed the expanded menu. While showing the first screen, we asked a participant to describe what he or she would expect to see under each main menu item. We also let other participants describe their expectations. For the retirement savings calculator, we asked what kind of specific information they would expect to have to input. We then discussed the inputs and got their reaction and what did or did not meet expectations. While this approach will not offer the same level of detail as a usability test, it can provide early insights into any major gaps before they become part of the design. By incorporating some scenario-based activities, it helped participants walk through the concepts and made it more (or less) real. This also helped the client realize the importance of user research as he or she moved into the design process.

Logistics

Over the course of three days, we held three 90-minute focus groups. We scheduled our focus groups in the evening to maximize participation. One hundred dollars and a light dinner was provided for focus group participants. In order to give participants enough time to arrive, eat, and get settled before the session started, we asked participants to arrive 20-30 minutes early. Even though the actual time for the focus group was 90 minutes, we set expectations that the session would take two hours.

We used our three-room suite lab, which we use for both usability testing and focus groups. For these focus groups, the participants sat around a table and the moderator stood at one end. We also had one notetaker present in the participant room to assist the moderator. See Figure 12.8 for an example of participants in the UXC participant room.

The design concepts and other material were presented on an overhead projector. We also provided printouts of the material so participants could have an alternative way to follow along.

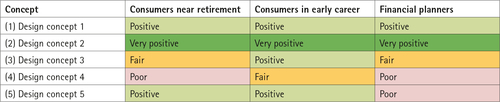

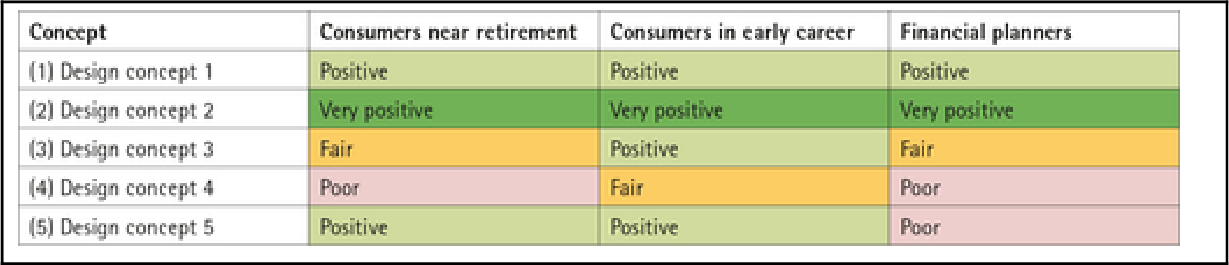

Analysis and Report

After running the focus group sessions, we took several days to review our notes and analyze the data. In our analysis, we were looking for trends and patterns within each design concept, across each focus group (user group) and global findings across all design concepts and focus groups. We produced a report in PowerPoint format. As a quick snapshot of the focus groups, we presented a table summarizing the overall impression for each design concept across each user group giving the client a glance at how the sessions went (Table 12.3).

Design concept 4 fared the worst. We made the recommendation that the concept should be reexamined. The rest of the report went into more detail about each design concept. We dedicated one slide per design concept, describing the overall impression by focus (user) group (e.g., main reasons they would or would not find it useful) with supporting user quotes. For example, for one design concept, participants were positive, but wanted the ability to chat with an advisor. We also made several recommendations to improve the design concept based on all the participant feedback. Finally, we ended the report with key takeaways and recommendations. We also provided overall recommendations when designing for each user group, regardless of design concept.

Key Takeaways When Running Focus Groups

For UX professionals that mostly use one-on-one research methods, such as usability testing and interviews, focus groups can seem a bit daunting; however, once you get the participants engaged and talking, you will find it a good technique for early research/brainstorming. I recommend using focus groups during the following instances:

■ Validating a concept before the design phase. You may learn that the concept needs to be tweaked or moved in a different direction.

■ Brainstorming with users in order to develop new ideas/concepts. Sometimes, you need to talk to users/customers/prospects to just understand the “what if.”

Of course, if you have an interactive prototype, I would recommend individual usability testing.

Recruiting and Logistics

■ Make sure the facility is accessible and inquire if any participants need any accommodations for accessibility.

■ If you use an outside recruiter, make sure you know whether the client/sponsor of the focus group should be hidden from participants (e.g., if confidentiality is required).

■ Inquire about any dietary restrictions for the snack/meal. Avoid loud snack options such as potato chips, as this may be distracting during the focus group.

Facilitation

■ Run at least one pilot session with a small number of friendly colleagues to run through timing. Practice any interactive techniques. We ran a pilot for this focus group, and it helped us refine our techniques and timing and increased our confidence before the first focus group.

![]() Test out all recording equipment during the pilot.

Test out all recording equipment during the pilot.

■ Pay attention to focus group best practices, especially in encouraging everyone to participate and not letting one participant dominate the discussion.

![]() Set the ground rules early—make sure everyone sets his or her mobile phone to vibrate.

Set the ground rules early—make sure everyone sets his or her mobile phone to vibrate.

![]() Use tent cards, so you can call on people by first name.

Use tent cards, so you can call on people by first name.

![]() If the focus group is more than an hour, provide a 5-minute break to use the restroom, etc.

If the focus group is more than an hour, provide a 5-minute break to use the restroom, etc.

■ Incorporate interactive activities where appropriate. This can also serve as a good way to break up the focus group or mix things up. Some examples include the following: