Choosing a User Experience Research Activity

Introduction

Now that you have gotten stakeholder buy-in, learned about your products and users, considered legal and ethical considerations, and arranged any facilities you may need, you are ready to choose the user experience research method that is best suited to answer your research question.

This chapter provides an overview of the methods presented in this book and a decision aid for choosing which methods will best help you answer your user experience research questions.

What It Takes to Choose a Method

Get the Right People Involved

If you are a consultant, you may join a project the moment the need for user experience research is recognized. If you work for a large company, your job may be to ensure that user experience research is used to drive all new product decisions. If you are a student, you may propose to do user research as part of your thesis or dissertation, or if you are a faculty member, you may propose to do user research as part of an application for funding. Who you need to get involved will depend on your situation. In industry, you often need to get stakeholder input (see Chapter 1, “Getting Stakeholder Buy-in for Your Activity” section, page 16) in addition to buy-in from the product team, whereas on a thesis or dissertation project you need to get input from committee members. Either way, you need to find out what stakeholders want to get out of the user research you are going to plan and conduct. Depending on your preferences and the stakeholders’ availability, a meeting may be the most effective way to get input from everyone who needs to be involved and thinking about the project. The goal of the meeting should be to answer the question: what do we want to know at the conclusion of the user experience research?

Ask the Right Questions

Once you have input from stakeholders, you need to transform everyone’s input into questions that can be answered via user research. There are some questions that cannot be answered and others that should not be answered via user research. User research is not intended to answer questions about business decisions (e.g., companies to acquire to expand product offerings, timing of feature releases) or marketing (e.g., how to brand your offering, market segmentation, how much people are willing to spend on your offering). Market research is about understanding what people will buy and how to get them to buy it. User research is about understanding how people think, behave, and feel in order to design the best interaction experience. This includes questions such as the following:

■ What do users want and need?

■ How do users think about this topic or what is their mental model?

■ What terminology do users use to discuss this topic?

■ What are the cultural or other influences that affect how a user will engage with your product?

■ What are the challenges and pain points users are facing?

Know the Limits

Now that you know what the fundamental questions are that you should seek to answer during your user research, you need to understand what limits there are that will further guide your decisions. The most common limits we see in user research are time, money, access to appropriate users or participants, potential for bias, and legal/ethical issues. While at first, these limits can seem problematic, we like to think of them as constraints that help guide the choice of a particular research methodology. For example, if you are conducting research about a socially sensitive topic, it is important to be aware that social desirability bias will likely be at play, and therefore, you need to choose a method that decreases the likelihood of this bias (e.g., anonymous survey rather than in-person interviews). If you have six months to inform the redesign of your company’s washer and dryer models, you may choose to spend a few weeks conducting field studies across the country with different demographic groups of potential customers. However, if you have only six weeks to complete all of your research, a one-week diary study may be more appropriate. The key here is that whatever method you choose should be based on your research question and scaled to the size you can accomplish given your constraints. Knowing these limits in advance will help you choose the best method for your research question, timeline, budget, and situation (see Figure 5.1).

The Methods

One of the myths surrounding user research is that it takes too much time and money. This is simply not true. There are activities that fit within every time frame and budget. While some can be designed to take months, others can be conducted in as little as two hours. Each type of activity provides different information and has different goals; we will help you understand what each of these is. Regardless of your budget or time constraints, in this book, you can find a user experience activity that will answer your questions and improve the quality of your product. The methods we cover are:

■ Interviews

■ Surveys

■ Card sorts

■ Focus groups

■ Field studies

■ Evaluation (e.g., usability tests)

We chose these methods for two reasons. First, each offers a different piece of the picture that describes the user. Second, using these methods, or a mix of these methods, you will be able to answer or triangulate an answer to almost any user research question you may encounter. In this section we provide a brief description of each method.

Diary Studies (Chapter 8)

Diary studies ask participants to capture information about their activities, habits, thoughts, or opinions as they go about their daily activities. These allow a researcher to collect in situ, typically longitudinal, data from a large sample. Diaries can be on paper or electronic and can be structured (i.e., participants are provided with specific questions) or unstructured (i.e., participants describe their experience in their own words and their own format). Both quantitative and qualitative data may be collected. Diary studies are often conducted along with other types of user research, such as interviews.

Interviews (Chapter 9)

Interviews are one of the most frequently used user research techniques. In the broadest sense, an interview is a guided conversation in which one person seeks information from another. There is a variety of different types of interviews you can conduct, depending on your constraints and needs. They are incredibly flexible and can be conducted as a solo activity or in conjunction with another user experience activity (e.g., following a card sort). Interviews can be leveraged when you want to obtain detailed information from users individually.

The end result of a set of interviews is an integration of perspectives from multiple users. If you conduct interviews with multiple user types of the same process/system/organization, you can obtain a holistic view. Finally, interviews can be used to guide additional user research activities.

Surveys (Chapter 10)

Surveys ask every user the same questions in a structured manner. Participants can complete them in their own time and from the comfort of their home or work. Since they can be distributed to a large number of users, you can typically collect much larger sample sizes than with interviews or focus groups. In addition, you can get feedback from people around the world; response rates can vary from 1% (charity surveys) to 95% (census surveys).

Card Sort (Chapter 11)

A card sort is most often used to inform or guide the development of the information architecture of a product. For example, it can help determine the hierarchy in applications. It can also provide information when deciding how to organize displays and controls on an interface.

To conduct the technique, each participant sorts cards describing objects or concepts in a product into meaningful groups. By aggregating the grouping created by several users, we can learn how closely related each of the concepts are. This method tells us how a product’s features should be structured to match the users’ expectations about how those features are related. This technique can be conducted with individuals or with a group of users working individually.

Focus Groups (Chapter 12)

In a focus group, six to ten users are brought together for an hour or two to provide information in response to a series of questions or to provide their subjective response to product demonstrations or concepts. Often, participants are given tasks to complete with prototypes of the product so they may have a better frame of reference from which to speak. Presenting the questions or product to a group sparks group discussion and can provide more information than interviewing individuals alone.

Focus groups are best suited for idea generation rather than formal evaluation and analysis. You can also discover problems, challenges, frustrations, likes, and dislikes among users; however, you cannot use focus groups to generalize the exact strength of users’ opinions, only that they are adverse to or in support of a concept or idea. If conducted well, a focus group can provide a wealth of useful information in a short period.

Field Studies (Chapter 13)

The term “field study” encompasses a category of activities that can include contextual inquiry, on-site interviews, simple observations, and ethnography. During a field study, a researcher visits users in their own environments (e.g., home or workplace) and observes them while they are going about their daily tasks. Field studies can last anywhere from a couple of hours to several days depending on the goals and resources of your study.

Using this technique, a UX professional gains a better understanding of the environment and context. By observing users in their own environment, you can capture information that affects the use of a product (e.g., interruptions, distractions, other task demands) and additional context that cannot be captured or replicated in a lab environment. Field studies can be used at any point during the product development life cycle but are typically most beneficial during the conceptual stage.

Evaluation Methods (Chapter 14)

Evaluation methods (e.g., usability tests) are a set of methods that focus on uncovering usability issues and determining whether new or redesigned products or services meet certain criteria. There are two general categories of evaluation methods: inspection methods, where trained UX/HCI professionals inspect an interface to assess its usability, and testing methods, where UX professionals observe users as they interact with a product or service. Evaluation criteria can include task success, time on task, page views, number of clicks, conversion, user satisfaction, ease of use, and usefulness. In addition, a list of issues uncovered is typically produced with proposed design improvements.

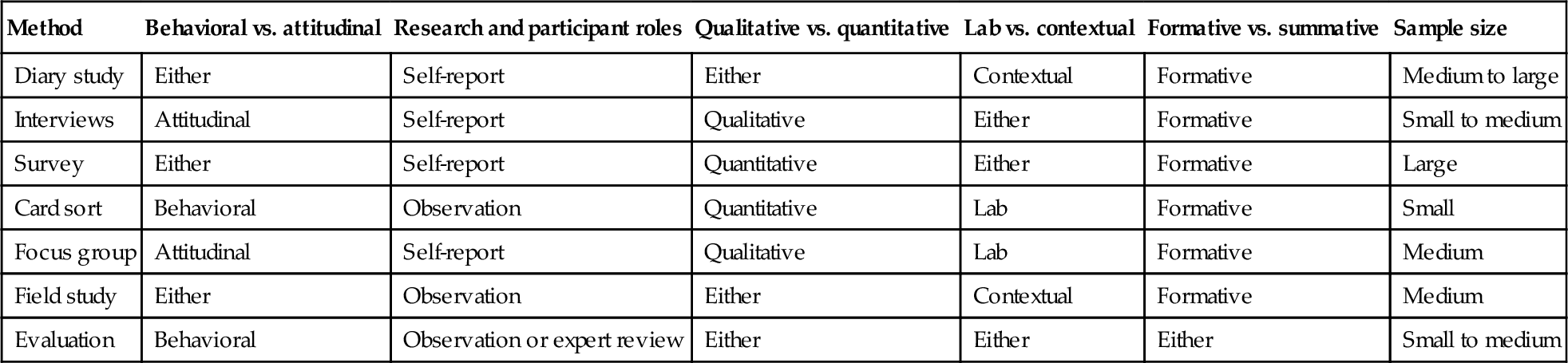

Differences Among the Methods

These methods also differ in terms of whether they address questions about behaviors or attitudes; include end users and if so, what they ask those end users to do; originate from different theoretical perspectives; collect words or data in numbers; and include where they are performed. We outline each of these considerations below. For an overview of how these methods differ along these dimensions, see Table 5.1.

Table 5.1

Summary of differences between methods

| Method | Behavioral vs. attitudinal | Research and participant roles | Qualitative vs. quantitative | Lab vs. contextual | Formative vs. summative | Sample size |

| Diary study | Either | Self-report | Either | Contextual | Formative | Medium to large |

| Interviews | Attitudinal | Self-report | Qualitative | Either | Formative | Small to medium |

| Survey | Either | Self-report | Quantitative | Either | Formative | Large |

| Card sort | Behavioral | Observation | Quantitative | Lab | Formative | Small |

| Focus group | Attitudinal | Self-report | Qualitative | Lab | Formative | Medium |

| Field study | Either | Observation | Either | Contextual | Formative | Medium |

| Evaluation | Behavioral | Observation or expert review | Either | Either | Either | Small to medium |

Note: This table presents a generalized summary of the most typical variation of each method. All methods can be/are adapted on each of these characteristics.

Behavioral vs. Attitudinal

While attitudes or beliefs and behaviors are related, for a variety of reasons, they do not always match (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). Because of this, it is important for you to decide which of these two, behaviors and attitudes, you are most interested in studying. If you want to know how people feel and talk about an organization or symbol, you are interested in their attitudes. If you want to know whether more people will click on a button that says “purchase flight” or “take me flying,” you are interested in behaviors. Some measures such as surveys are more appropriate for measuring attitudes, whereas other methods such as field studies allow you to observe behaviors. However, be certain to remember that attitudes and behavior are related; even if you or your stakeholders are primarily interested in behaviors for one study, you cannot disregard attitudes; attitudes can drive behaviors over the long term.

Research and Participant Roles

Related to issues of attitude and behavior are the roles of the researcher and participant in the research. Some methods rely entirely on self-report, which means that a participant provides information from memory about him or herself and his or her experiences. In contrast, other methods collect observations. Observational studies rely on the researcher watching, listening, and otherwise sensing what a participant does, rather than asking him or her to report what he or she does or thinks. Finally, some methods do not involve participants at all and instead rely on the experience of experts. These types of studies are called expert reviews.

Lab vs. Contextual

Conducting studies in a lab environment (see page 87) allows you to control many potential confounds in your study and is useful for isolating how one variable impacts another. However, the lab environment lacks contextual cues, information, people, and distractions that participants will have to contend with when they use your product in real life. When you are considering methods, realize that some methods, such as field studies, allow you to understand the users’ context. Others, such as lab-based usability tests, provide control over these contextual factors, so you can focus on the product in isolation.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative

Qualitative suggests data that include a rich verbal description, whereas quantitative suggests data that are numeric and measured in standard units. Qualitative data, such as open-ended interview responses, can be quantified. For example, you could use a content analysis to determine the number of times a certain word, phrase, or theme was expressed across participants. However, the root of the difference between these approaches is deeper and related to disciplinary traditions potentially making quantifying qualitative data unappealing. To answer many research questions thoroughly, you need to combine these approaches.

Formative vs. Summative

Formative evaluations are conducted during product development or as a product is still being formed. The goal is to influence design decisions as they are being made. In formative research, you can figure out what participants think about a topic, determine when a feature is not working well and why, and suggest changes based on those findings. Summative evaluations are conducted once a product or service is complete. The goal is to assess whether the product or service meets standards or requirements. In summative research, you can determine whether a product is usable by some standard measure, such as number of errors or time on task.

Number of Users

While some types of studies require a large participant population to provide the most useful information (e.g., surveys), others can be conducted with a relatively low N and still provide significant value (e.g., usability tests). Determining how many users you need for any study can seem like a daunting task. For any study, there are a number of considerations that come into play when you are trying to determine sample size, such as available resources (e.g., time to complete study, funds to pay participants, number of prototypes), size of the effect you are looking for, the population you would like to extrapolate your findings to, the confidence you need to have in your findings, the type of contribution you would like to make, and your experience, comfort, and preferences for determining sample size. There are a number of straightforward ways, however, that can help you determine how many participants you need, including power analysis, saturation, cost or feasibility analysis, and heuristics.

Power Analysis

For quantitative studies where you will draw statistical inferences, you can determine how many participants you need using a power analysis. A power analysis considers the type of statistical test you plan to conduct, the significance level or confidence you desire (more confidence = lower power), the size of the effect you expect (bigger effect = more power), the level of “noise” in your data (more noise or higher standard deviation = lower power), and the sample size (N; higher sample size = more power). If you know three of these factors, you can determine the fourth, which means you can use this type of analysis to determine the sample size you would need to be able to confidently and reliably detect an effect.

There are a number of ways to calculate power including the following:

■ Using online calculators

![]() https://www.measuringusability.com/problem_discovery.php

https://www.measuringusability.com/problem_discovery.php

![]() http://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm

http://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm

![]() http://www.resolutionresearch.com/results-calculate.html

http://www.resolutionresearch.com/results-calculate.html

![]() http://hedwig.mgh.harvard.edu/sample_size/js/js_parallel_quant.html

http://hedwig.mgh.harvard.edu/sample_size/js/js_parallel_quant.html

■ In stats packages

![]() SPSS

SPSS

If you would like to use a power analysis to determine the number of participants for an upcoming study but are not comfortable using the methods above, we recommend the following:

■ Consult Quantifying the User Experience (especially Chapter 7, Sauro & Lewis, 2012) for a historically grounded and thorough description and explanation of sample size calculations for formative research.

■ Take a statistics class. Classes are offered at local technical colleges, at universities, and in specialized UX stats workshops.

■ Hire a consultant with expertise in quantitative analysis. Many universities have statistical consultants and/or biostatisticians on staff who will perform a power analysis for you for a reasonable fee.

Saturation

For qualitative studies, it may not be possible to determine in advance how many participants you will need. Unlike many quantitative approaches, in some qualitative approaches, the qualitative researcher is analyzing data throughout the study. Data saturation is the point during data collection at which no new relevant information emerges. While reaching saturation is the ideal, because it is not possible to predict in advance when saturation will be reached, this method may be hard to justify to other stakeholders or make study logistics difficult.

Cost/Feasibility Analysis

While power analysis and saturation are the ideal ways to determine the number of participants to recruit for a study, in reality, we often find that researchers are not able to fulfill this ideal. Instead, life comes into play: you have a limited budget with which to remunerate participants, you have five days within which to meet with participants, you have to collect all data for your dissertation over the summer, and your lab does not have funding for you to travel to meet participants in more than three locations. In these situations, two methods you can use to determine sample size are cost and feasibility analyses.

Cost or ROI Analysis

Sometimes, the one constraint you know going into a project is how much money you have to spend. Under these circumstances, a cost analysis can help you determine how many participants you can recruit for your study. The simplest, most basic, least-informed analysis is

Feasibility Analysis

Besides monetary costs, there are often other constraints as you plan a study. Constraints include time to complete the study, participant availability, and number of participants that exist (e.g., the population of fighter jet pilots is much more limited than the number of mobile phone owners). For physical products, you must also consider the number of prototypes, bandwidth, number of researchers available, space, equipment (e.g., fMRI machine), and client requirements.

Using a feasibility analysis, you can use the constraints you know to guide the number of participants you sample. For example, let us say your client wants to know how technology could be used to improve the local hospital emergency room discharge process. They ask you to conduct focus groups and want to get the perspective of patients, providers, and hospital administrators. As you work with the client, a major constraint is imposed: you only have time and location resources to conduct four focus groups. You explain that this constraint will limit the reliability and depth of your results, but the client explains that this is the only option. You agree that some data are better than no data.

You can use this constraint to guide how you configure the focus groups. There are only eight hospital administrators in the entire hospital, so these can all fit in one group. Similarly, there are only 30 EHR doctors and nurses, so you can sample around 30% of them in one focus group. However, there are tens of thousands of patients, so you know you should devote at least two groups to them. Alternatively, you could present the option to the client to only study the perceptions of patients, devoting all four focus groups to patients only. This, you argue, would allow you to get a more reliable understanding of the patient perspective. If this portion of the study goes well, you think it might be possible to do a follow-up study with the doctors and nurses and administrators.

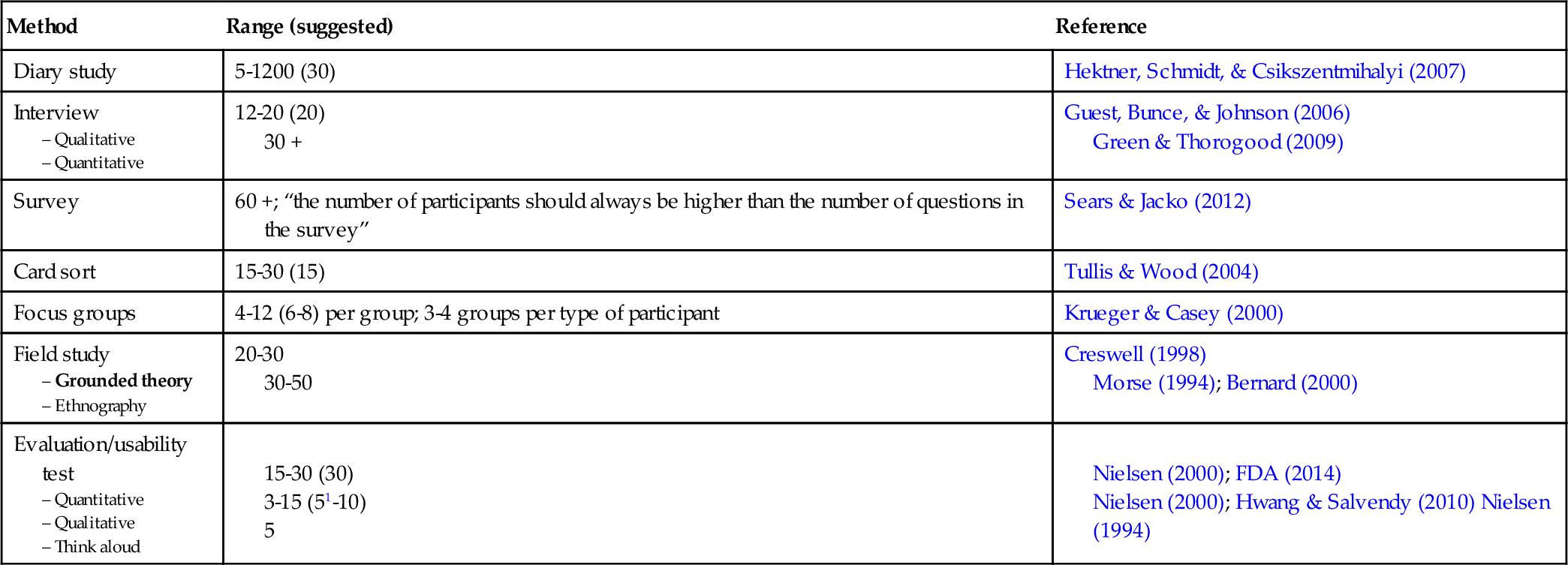

Heuristics

There are two types of heuristics for determining sample size: previous similar or analogous studies (or “local standards”) and recommendations by experts.

Previous Similar or Analogous Studies (Local Standards)

To find out the local standards in your organization or community, ask colleagues how many participants they have used for studies similar to the one you are planning. If you plan to publish your work, read recently published papers from the venue where you plan to submit your work to determine community norms.

Recommendations by Experts

Experts are people who have worked in a field with success for a long time. Because of their expertise, they are often trusted as sources of information about a topic. For convenience, we have compiled a table that summarizes sample size recommendations based on expert opinion for each type of study we discuss in this book. This is presented in Table 5.2. This summary presents only a range and suggested sample size and does not detail the reasoning, justification, or description that exists in the cited reference. Please refer to the original source for more information, and use these recommendations from experts with care.

Table 5.2

Heuristics for number of participants for each study type

| Method | Range (suggested) | Reference |

| Diary study | 5-1200 (30) | Hektner, Schmidt, & Csikszentmihalyi (2007) |

| Interview – Quantitative | 12-20 (20) 30 + | Guest, Bunce, & Johnson (2006) Green & Thorogood (2009) |

| Survey | 60 +; “the number of participants should always be higher than the number of questions in the survey” | Sears & Jacko (2012) |

| Card sort | 15-30 (15) | Tullis & Wood (2004) |

| Focus groups | 4-12 (6-8) per group; 3-4 groups per type of participant | Krueger & Casey (2000) |

| Field study – Ethnography | 20-30 30-50 | Creswell (1998) Morse (1994); Bernard (2000) |

| Evaluation/usability test – Qualitative – Think aloud | 15-30 (30) 3-15 (51-10) 5 | Nielsen (2000); FDA (2014) Nielsen (2000); Hwang & Salvendy (2010) Nielsen (1994) |

1 Given a straightforward task; per design iteration.

Sampling Strategies

In an ideal world, a user research activity should strive to represent the thoughts and ideas of the entire user population. Ideally, an activity is conducted with a representative random sample of the population so that the results are highly predictive of the entire population. This type of sampling is done through precise and time-intensive sampling methods. In reality, this is rarely done in industry settings and only sometimes done in academic, medical, pharmaceutical, and government research.

In industry user research, convenience sampling is often used. When employed, the sample of the population used reflects those who were available (or those you had access to) at a moment in time, as opposed to selecting a truly representative sample of the population. Rather than selecting participants from the population at large, you recruit participants from a convenient subset of the population.

The unfortunate reality of convenience sampling is that you cannot be positive that the information you collect is truly representative of your entire population. We are certainly not condoning sloppy data collection, but as experienced user research professionals are aware, we must strike a balance between rigor and practicality. For example, you should not avoid doing a survey because you cannot obtain a perfect sample. However, when using a convenience sample, still try to make it as representative as you possibly can. Other nonprobability-based sampling strategies we see used are snowball sampling, where previous participants suggest new participants, and purposive sampling, where participants are selected because they have a characteristic of interest to the researcher. One problem with snowball sampling is that you tend to get self-consistent samples because people often know and suggest other potential participants who are similar to themselves.

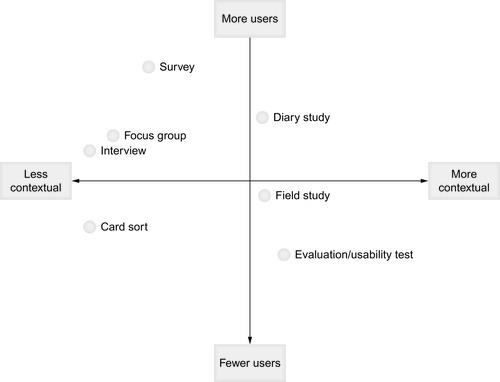

Figure 5.2 presents a graphical representation of general guidelines about how many participants are required for each type of study by study contextualization. An overview of sample size considerations is provided in this chapter, and a thorough discussion of number of participants is provided in each methods chapter.

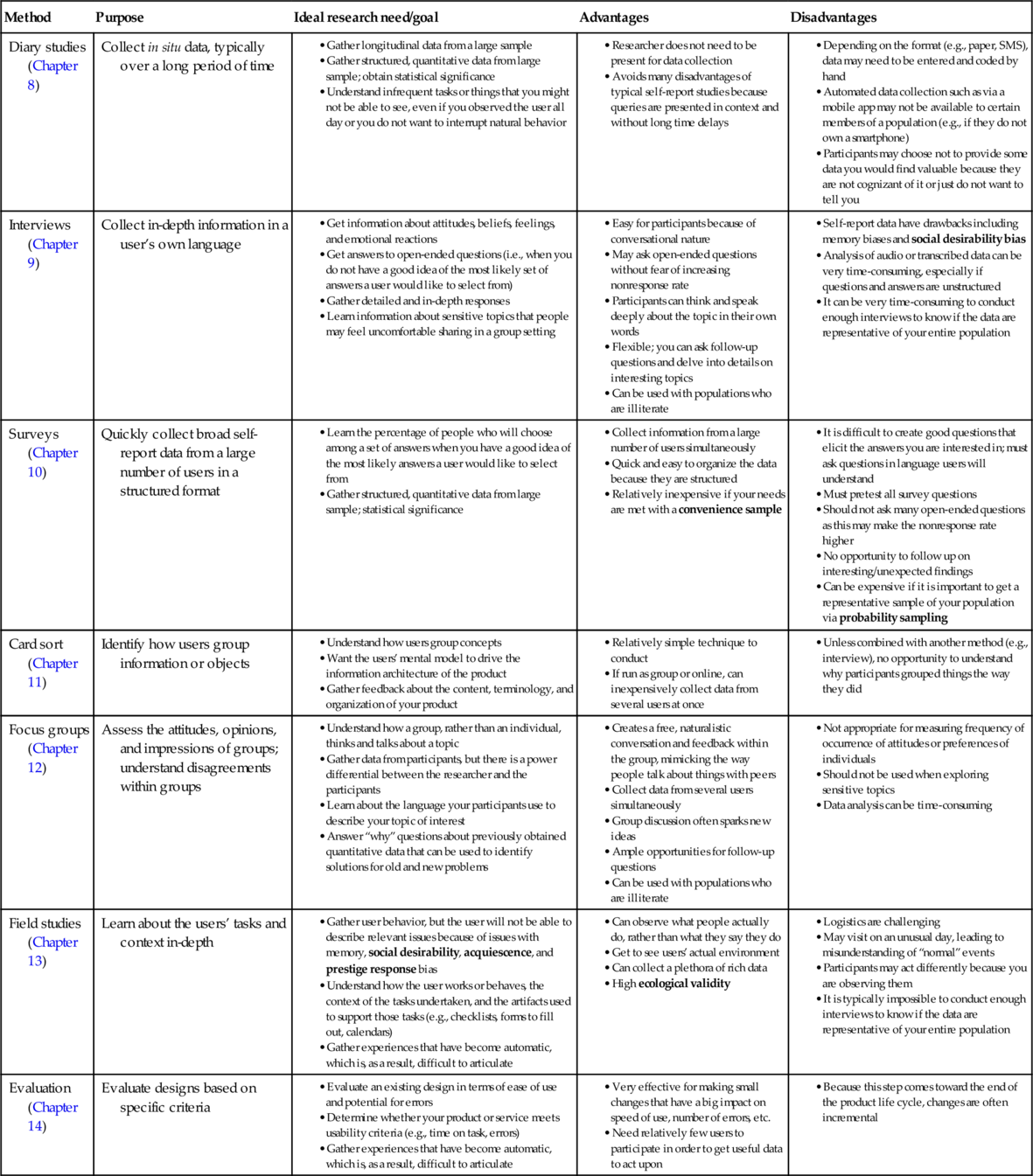

Choosing the Right Method

As you can see, these seven sets of methods provide you with a variety of options. Some techniques can be intensive in time and resources (depending on your design) but provide a very rich and comprehensive data set. Others are quick and low-cost and provide the answers you need almost immediately. Each of these techniques can provide different data to aid in the development of your product or service. Your job as a researcher is to understand the trade-offs being made—in cost, time, accuracy, representativeness, etc.—and to present those trade-offs as you present the results and recommendations. It is important that you choose the correct activity to meet your needs and that you understand the pros and cons of each. In Table 5.3, we outline each of the activities proposed in this book and review what it is used for and present its advantages and disadvantages. If you are unfamiliar with these research methods, this table might not make sense to you right now. That is OK. Think of the tables in this chapter as a reference to use as you read the book or as you are deciding which method is right for your research question.

Table 5.3

Comparison of user research techniques presented in this book

| Method | Purpose | Ideal research need/goal | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Diary studies (Chapter 8) | Collect in situ data, typically over a long period of time |

• Gather longitudinal data from a large sample • Gather structured, quantitative data from large sample; obtain statistical significance • Understand infrequent tasks or things that you might not be able to see, even if you observed the user all day or you do not want to interrupt natural behavior |

• Researcher does not need to be present for data collection • Avoids many disadvantages of typical self-report studies because queries are presented in context and without long time delays |

• Depending on the format (e.g., paper, SMS), data may need to be entered and coded by hand • Automated data collection such as via a mobile app may not be available to certain members of a population (e.g., if they do not own a smartphone) • Participants may choose not to provide some data you would find valuable because they are not cognizant of it or just do not want to tell you |

| Interviews (Chapter 9) | Collect in-depth information in a user’s own language |

• Get information about attitudes, beliefs, feelings, and emotional reactions • Get answers to open-ended questions (i.e., when you do not have a good idea of the most likely set of answers a user would like to select from) • Gather detailed and in-depth responses • Learn information about sensitive topics that people may feel uncomfortable sharing in a group setting |

• Easy for participants because of conversational nature • May ask open-ended questions without fear of increasing nonresponse rate • Participants can think and speak deeply about the topic in their own words • Flexible; you can ask follow-up questions and delve into details on interesting topics • Can be used with populations who are illiterate |

• Self-report data have drawbacks including memory biases and social desirability bias • Analysis of audio or transcribed data can be very time-consuming, especially if questions and answers are unstructured • It can be very time-consuming to conduct enough interviews to know if the data are representative of your entire population |

| Surveys (Chapter 10) | Quickly collect broad self-report data from a large number of users in a structured format |

• Learn the percentage of people who will choose among a set of answers when you have a good idea of the most likely answers a user would like to select from • Gather structured, quantitative data from large sample; statistical significance |

• Collect information from a large number of users simultaneously • Quick and easy to organize the data because they are structured • Relatively inexpensive if your needs are met with a convenience sample |

• It is difficult to create good questions that elicit the answers you are interested in; must ask questions in language users will understand • Must pretest all survey questions • Should not ask many open-ended questions as this may make the nonresponse rate higher • No opportunity to follow up on interesting/unexpected findings • Can be expensive if it is important to get a representative sample of your population via probability sampling |

| Card sort (Chapter 11) | Identify how users group information or objects |

• Understand how users group concepts • Want the users’ mental model to drive the information architecture of the product • Gather feedback about the content, terminology, and organization of your product |

• Relatively simple technique to conduct • If run as group or online, can inexpensively collect data from several users at once |

• Unless combined with another method (e.g., interview), no opportunity to understand why participants grouped things the way they did |

| Focus groups (Chapter 12) | Assess the attitudes, opinions, and impressions of groups; understand disagreements within groups |

• Understand how a group, rather than an individual, thinks and talks about a topic • Gather data from participants, but there is a power differential between the researcher and the participants • Learn about the language your participants use to describe your topic of interest • Answer “why” questions about previously obtained quantitative data that can be used to identify solutions for old and new problems |

• Creates a free, naturalistic conversation and feedback within the group, mimicking the way people talk about things with peers • Collect data from several users simultaneously • Group discussion often sparks new ideas • Ample opportunities for follow-up questions • Can be used with populations who are illiterate |

• Not appropriate for measuring frequency of occurrence of attitudes or preferences of individuals • Should not be used when exploring sensitive topics • Data analysis can be time-consuming |

| Field studies (Chapter 13) | Learn about the users’ tasks and context in-depth |

• Gather user behavior, but the user will not be able to describe relevant issues because of issues with memory, social desirability, acquiescence, and prestige response bias • Understand how the user works or behaves, the context of the tasks undertaken, and the artifacts used to support those tasks (e.g., checklists, forms to fill out, calendars) • Gather experiences that have become automatic, which is, as a result, difficult to articulate |

• Can observe what people actually do, rather than what they say they do • Get to see users’ actual environment • Can collect a plethora of rich data • High ecological validity |

• May visit on an unusual day, leading to misunderstanding of “normal” events • Participants may act differently because you are observing them • It is typically impossible to conduct enough interviews to know if the data are representative of your entire population |

| Evaluation (Chapter 14) | Evaluate designs based on specific criteria |

• Evaluate an existing design in terms of ease of use and potential for errors • Determine whether your product or service meets usability criteria (e.g., time on task, errors) • Gather experiences that have become automatic, which is, as a result, difficult to articulate |

• Very effective for making small changes that have a big impact on speed of use, number of errors, etc. • Need relatively few users to participate in order to get useful data to act upon |

• Because this step comes toward the end of the product life cycle, changes are often incremental |

In addition to teaching you how to conduct each of these methods, this book can help you choose the best method(s) for your research question. Table 5.2 gives examples of various research needs and matches those with appropriate methods to use in each case. Use this table to help you determine which method is right for your research question.