Interviews

Introduction

Interviews are one of the most frequently-used methods for understanding your users. In the broadest sense, an interview is a guided conversation in which one person seeks information from another. There are a variety of different types of interviews you can conduct, depending on your constraints and needs. They are flexible and can be used as a solo activity or in conjunction with another user research activity (e.g., following a card sort or in combination with a contextual observation).

In this chapter, we discuss how to prepare for and conduct an interview, how to analyze the data, and how to communicate the findings to your team. We spend a good deal of time concentrating on constructing good interview questions and how to interact with participants to get the best data possible. These processes are critical to a successful interview. Finally, we close this chapter with an illustrative case study about conducting interviews with children.

Preparing to Conduct an Interview

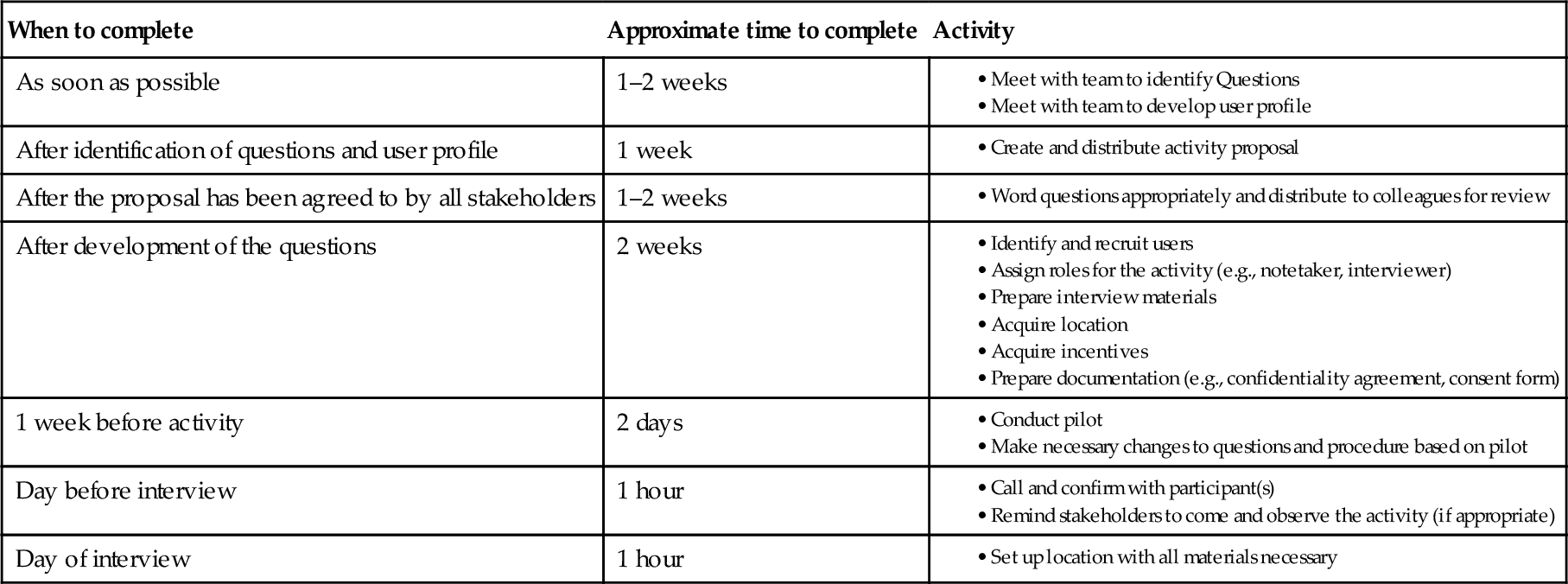

Preparing for an interview includes selecting the type of interview to conduct, wording the questions, creating the materials, training the interviewer, and inviting observers. See Table 9.1 for a high-level timeline to follow as you prepare for an interview.

Table 9.1

Preparing for the interview session

Identify the Objectives of the Study

When developing questions for interviews, it is easy to add more and more questions as stakeholders (i.e., product team, management, partners) think of them. That is why it is important for everyone to agree upon the purpose and objectives of the study from the beginning. These objectives should be included in your proposal to the stakeholders and signed off by all parties (see Chapter 6, “Creating a Proposal” section, page 116). As you and the stakeholders determine the type of interview to conduct and brainstorm questions for the interview, use the objectives of the study as a guide. If the type of interview suggested or the questions offered do not match the objectives that have been agreed upon, the request should be denied. This is much easier to do once the proposal has been signed off, rather than trying to get the agreement halfway through the process.

Select the Type of Interview

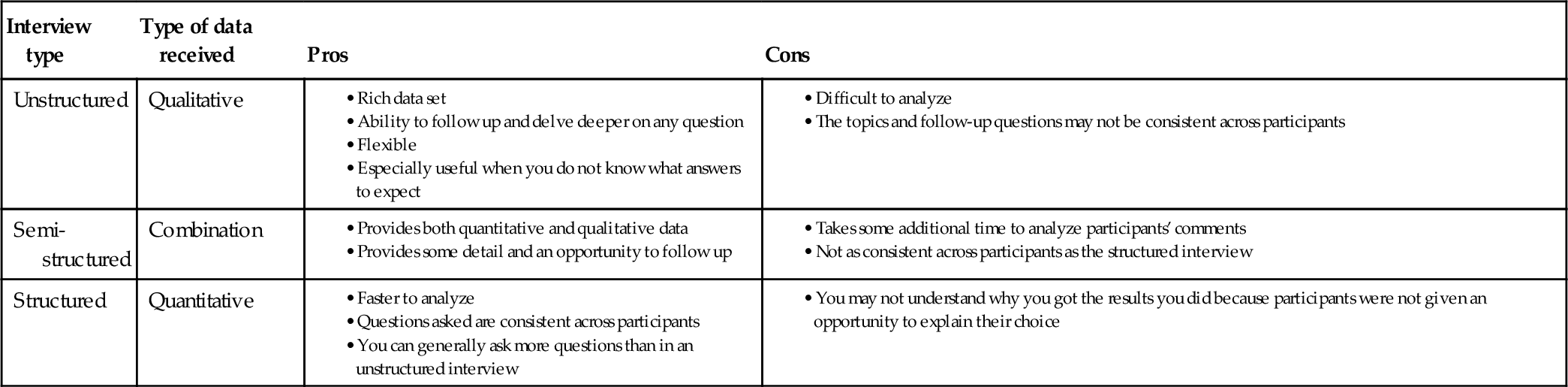

Interviews vary by the amount of control the interviewer places on the conversation. There are three main types of one-on-one interview:

■ Structured

■ Semi-structured

An unstructured interview is the most similar to a normal conversation. The interviewer will begin with general goals but will allow the participant to go into each point with as much or as little detail and in the order he or she desires. The questions or topics for discussion are open-ended (see Chapter 10, “Response Format” section, page 275), so the interviewee is free to answer in narrative form (i.e., not forced to choose from a set of predetermined answers), and the topics do not have to be covered in any particular order. The interviewer is also free to deviate from the script to generate additional relevant questions based on answers given during the interview. When deviating from the script, it is important to be able to think on your feet so you can focus on getting the most important information, even if the question that will get you that information is not in the script. It is a good idea to have a list of carefully worded follow-up questions already prepared so you do not have to come up with these on the fly.

A structured interview, on the other hand, is the most controlled type because the goal is to offer each interviewee the same set of possible responses. The interview may consist primarily of closed-ended questions (see Chapter 10, “Response Format” section, page 275), where the interviewee must choose from the options provided. This presents a limit because a closed-ended question is only effective if the choices offered are complete and presented in the users’ vernacular. Furthermore, participants tend to confine their answers to the choices offered, even if the choices are not complete. Open-ended questions may be asked, but the interviewer will not delve into the participant’s responses for more details or ask questions that are not listed on the script. All possible questions and follow-ups are preplanned; therefore, the data gathered across participants are consistent. Thus, differences in results are attributable to real differences between participants rather than differences in measurement technique. This type of interview is similar to conducting a survey verbally but has the added benefit of allowing participants to explain their answers. It is used by organizations like the Census Bureau and Bureau of Labor Statistics.

A semi-structured interview is clearly a combination of the structured and unstructured types. The interviewer may begin with a set of questions to answer (closed-ended and open-ended) but deviate from the order and even the set of questions from time to time. The interview does not have quite the same conversational approach as an unstructured one.

When determining the type of interview to conduct, keep the data analysis and objectives of the study in mind. By first deciding the type of interview you plan to conduct, you know the type of questions you will be able to ask. As with any method, there are pros and cons to each type of interview (see Table 9.2).

Table 9.2

Comparison of the three types of interview

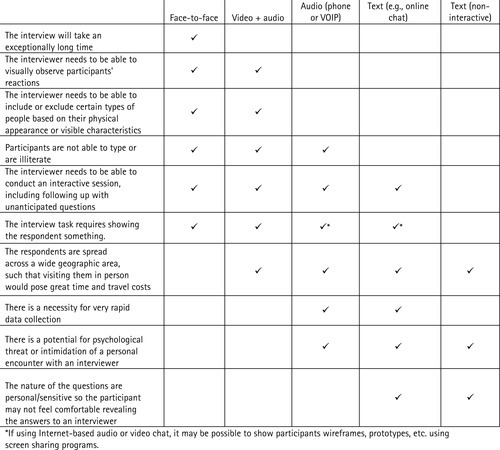

In Person or Mediated?

Regardless of the type of interview you select, you have the option of conducting the interviews in an increasingly large number of ways, including (listed from the least mediated to the most mediated) in person, using video conferencing/video chat, over the phone, or via text chat. Some aspects of mediated interviews are easier than in-person interviews. For example, when conducting interviews via text chat, there is no need to have a conversation transcribed, because all data are already captured as text. It is also usually more convenient for both the participant and interviewer to conduct the interviews via a mediated channel so that less time is spent on travel. However, there are also disadvantages to conducting interviews that are not face-to-face:

■ Participants may end interviews on the telephone before participants in face-to-face interviews. It can be difficult to keep participants on the phone for more than 20 minutes. If you are cold-calling participants (i.e., not a prescheduled interview), the biggest challenge may be keeping the participant’s attention. If you do not have the participant in a quiet location, it is easy for his or her colleagues or children to come in during your interview for a “quick” question.

■ Similarly, in all mediated interviews except video chat, both participants and the interviewer lack cues about identity and lack nonverbal communication cues. This may lead participants to take a more cautious approach to revealing sensitive information (Johnson, Hougland, & Clayton, 1989). It also means that you cannot watch the participant’s body language, facial expressions, and gestures, which can all provide important additional information.

■ Phones can be perceived as impersonal, and it is more difficult to develop a rapport with the participant and engage him or her over the phone.

An additional benefit of computer-mediated interviews rather than phone-mediated interviews is that you may show artifacts to participants if appropriate. Figure 9.1 provides a checklist that can help you determine which type of interview is most appropriate.

Decide Now How You Will Analyze the Data

Whether you are asking closed-ended or open-ended questions, there are tools and methods available to help you analyze your data. For a discussion of how to analyze open-ended questions, see “Data Analysis and Interpretation” section on page 252. For a discussion of how to analyze closed-ended questions, refer to Chapter 10 on page 266.

However you choose to analyze your data, you should analyze some sample data from your pilot interviews to ensure that your analysis strategy is achieving the results you want and to help you understand whether you need to adjust your questions (see Chapter 6, “Piloting Your Activity” section, page 155). If you plan to use a new tool, be sure to allow time to purchase any necessary software and learn how to use it.

Identify the Questions

It is now time to identify all the questions to ask. You may want to do initial brainstorming with all stakeholders (members of the product team, UX, marketing). You will likely end up with questions that are out of the scope of the proposed activity or questions that are best answered by other activities. The questions that are out of the scope should be discarded, and the ones that are better answered by other activities should be put aside until the other activity can be performed. Even with limiting your questions in this way, you may still end up with more questions than you could possibly cover in a single interview. If this is the case, you will either need to conduct multiple sessions or focus on the most important topics, so you can trim down the number of questions to fit into a single session.

Write the Questions

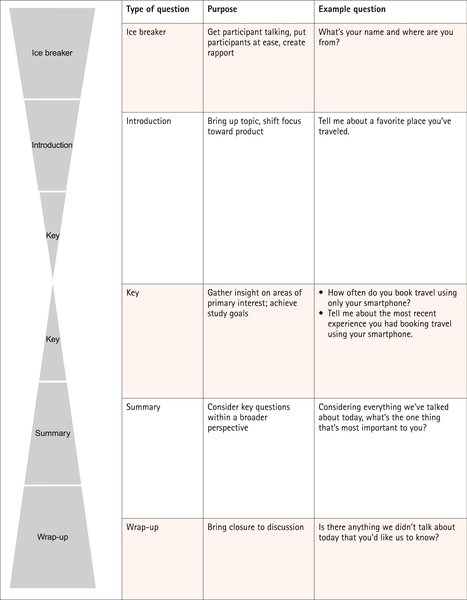

Once you have a list of topics you are interested in, now is the time to write a first draft of the questions. One way to start this process is by making sure you have questions that fit each category of question necessary for the interview flow. Table 9.3 presents an overview of an idealized interview flow. The next step is to word the questions so that they are clear, understandable, and impartial. In the next section, we describe how to write good questions and provide examples and counter-examples.

Brevity

Questions should be kept short—usually 20 words or less. It is difficult for people to remember long or multiple-part questions. Break long, complex questions into two or more simple questions.

Clarity

Avoid double-barreled questions that address more than one issue at a time. Introducing multiple issues in a question can be confusing. The example below addresses multiple issues: the frequency of traveling, the frequency of booking travel online, and the purpose for booking travel online. These should be asked separately.

Vague questions, too, can cause difficulty during an interview. Avoid imprecise words like “rarely,” “sometimes,” “usually,” “few,” “some,” and “most.” Individuals can interpret these terms in different ways, affecting their answers and your interpretation of the results.

A final challenge to creating clear questions is the use of double negatives. Just as the name implies, double negatives insert two negatives into the sentence, making it difficult for the interviewee to understand the true meaning of the question.

Avoiding Bias

As we mentioned earlier, there are a number of ways in which you might introduce bias into questions. One way is with leading questions. These questions assume the answer and may pass judgment on the interviewee. They are designed to influence a participant’s answers rather than elicit the participant’s true opinion.

Leading questions are rather obvious and easy to pick up on. Loaded questions are subtler in their influence. They typically provide a “reason” for a problem in the question. One example where loaded questions may be observed is in political campaigns. Politicians may use these type of questions in an attempt to demonstrate that a majority of the population feels one way or another on a key issue.

The question above suggests that the reason for increasing travel costs is increased security costs. It is clear how the interviewer in the first (wrong) question would like the participant to answer. This is also an example of a question based on a false premise. The example implies that the government has not paid for additional security costs and should now start to do so. These types of questions begin with a hypothesis or assumption that may not be fully accurate or can be easily misinterpreted. Not only is this type of question unethical, but also the data you get in the end are not valid.

The final type of bias is interviewer prestige bias. In this case, the interviewer informs the interviewee that an authority figure feels one way or another about a topic and then asks the participant how he or she feels.

Focus on Outcomes

Rather than asking your participants for solutions to problems or to identify a specific product feature that they might like, ask participants questions that help you ascertain the outcomes they need to achieve. People are often unable to know what works for them or what they may actually like until they have actual experience with a service or feature.

The “wrong” question above would be a problem if the participant was unfamiliar with instant messaging. In that case, you would want to speak in broader terms and ask the participant to discuss communications methods with which he or she is familiar.

If you task customers with the responsibility of innovation, many problems can occur, such as small iterative changes rather than drastic, pioneering changes; suggestions that are limited to features available in your competitors’ products (because these are what your participants are familiar with); and features that users do not actually need or use (most users use less than 10% of a software product). Focusing on outcomes lets you get a better understanding of what users really need. With a thorough understanding of what participants need, you can allow developers, who have more technical knowledge and desire to innovate than users, to create innovative solutions that meet these needs.

To do this, the interviewer must understand the difference between outcomes and solutions and ask the appropriate probes to weed out the solutions while getting to the outcomes.

Avoid Asking Participants to Predict the Future

Do not expect participants to be able to predict their future. Instead, focus on understanding what they want now. You will be able to translate that into what they will need in the future.

Inaccessible Topics

You have screened your participants against the user profile, but you still may encounter those who cannot answer all of your questions. A participant may not have experience with exactly what you are asking about or may not have the factual knowledge you are seeking. In these cases, be sure a participant feels comfortable saying that he or she does not know the answer or does not have an opinion. Forcing a participant to choose an answer will only frustrate the participant and introduce error into your data.

Begin the interviews by informing participants that there are no right or wrong answers—if they do not have an opinion or experience with something, they should feel free to state that. Keep in mind that interviewees are often eager to please or impress. They may feel compelled to answer and therefore make a best guess or force an opinion that they do not actually have. Encourage them to be honest and feel comfortable enough to say they cannot answer a particular question.

Depending on Memory

Think about the number of times you have booked a rental car in the last three years. Are you confident in your answer? Interviewers and surveys often ask people how frequently they have done a certain task in a given period. If the question seeks information about recent actions or highly memorable events (e.g., your wedding, college graduation), it probably will not be too difficult. Unfortunately, people are often asked about events that happened many years ago and/or those that are not memorable.

What is key is the importance or salience of the event. Some things are easily remembered because they are important or odd and therefore require little effort to remember. Other things are unmemorable—even if they happened yesterday, you would not remember them. In addition, some memories that seem real may be false. Since most participants want to be “good” interviewees, they will try hard to remember and provide an accurate answer, but memory limitations prevent it. Underreporting and overreporting of events frequently happen in these cases.

In addition to memory limitations, people have a tendency to compress time. This response bias is known as telescoping. This means that if you are asking about events that happened in the last six months, people may unintentionally include events that happened in the last nine months. Overreporting of events will result in these cases.

To help mitigate these sources of error, you should avoid questions covering unmemorable events. Focus the questions on salient and easy-to-remember events. You can also provide memory aids like a calendar and/or provide specific instructions alerting participants to potential memory confusion and encouraging them to think carefully to avoid such confusion (Krosnick, 1999). Finally, if you are truly interested in studying events over a period of time, you can contact participants in advance and ask them to track their behaviors in a diary (see Chapter 8, “Incident Diaries” section, page 202). This means extra work for the participant, but the data you receive from those dedicated individuals who follow through will likely be far more accurate than from those who rely on memory alone.

Other Types of Wording to Avoid

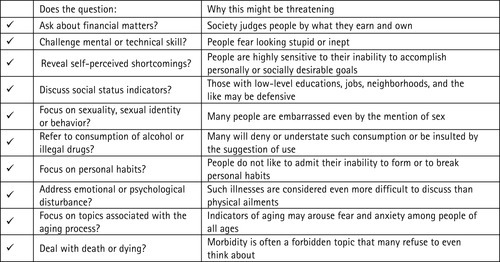

Avoid emotionally laden words like “racist” and “liberal.” Personal questions should be asked only if absolutely necessary and then with great tact. This includes questions about age, race, and salary. Figure 9.2 describes how to identify questions that might be perceived as threatening.

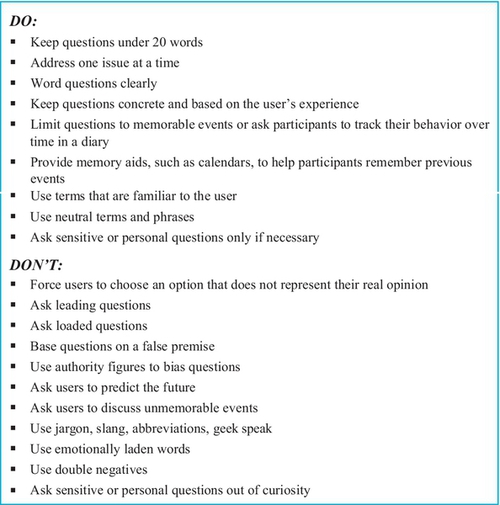

Jargon, slang, abbreviations, and geek speak should be avoided unless you are certain that your user population is familiar with this terminology. Speaking plainly and in the user’s language (as long as you understand it) is important. And of course, take different cultures and languages into consideration when wording your questions (see Chapter 6, “Recruiting International Participants” section, page 147). A direct word-for-word translation can result in embarrassing, confusing, or misinterpreted questions. Figure 9.3 provides a checklist of dos and don’ts in question wording.

Test Your Questions

It is important to test your questions to ensure that you are covering all the topics you mean to, to identify questions that are difficult to understand, and to ensure that questions will be interpreted as you intend. If you are conducting an unstructured interview, test your list of topics. If you are conducting a structured interview, test each of your questions and follow-up prompts. Begin with members of your team who have not worked on the interview so far. The team members should be able to summarize the type of information you are looking for in a question. If the colleague incorrectly states the information you are seeking, you need to clarify or reword the question. Find someone who understands survey and interview techniques to check your questions for bias. If no one in your organization has experience with survey and interview techniques, you may be able to ask a colleague in another organization to review your questions for bias, as long as the questions will not reveal proprietary information.

Once the questions have passed the test of colleagues, conduct the interview with a couple of actual participants. How did the participants react to the questions? Did they answer your question, or did it seem like they answered another question? Was everything clear? Were you able to complete the interviews within the allotted time frame?

Players in Your Activity

In addition to users (the “participants”), you will require three other people to run the sessions. In this section, we discuss the details of all the players involved in an interview.

The Participants

Participants should be representative of your existing end users or the users that you expect will be interacting with your system.

Number of Participants

We find in industry settings that a common sample size for interview studies is six to ten participants of each user type, with the same set of questions. However, there are several factors to take into consideration, including whether you are seeking qualitative or quantitative data and the size of the population of users. For qualitative studies, some researchers recommend that 12 participants are sufficient for discovering new themes (Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006). On the other hand, other researchers suggest that thirty or more participants are needed for interviews seeking quantitative data (Green & Thorogood, 2009). See Chapter 6 on page 116 for a more thorough discussion of how many participants you should recruit for a user research activity.

The Interviewer

The task of the interviewer is to develop rapport with the interviewee, elicit responses from the participant, know what an adequate answer is to each question, examine each answer to ensure that the participant understands what he or she is really saying, and, in some cases, paraphrase the response to make sure that the intent of the statement is captured. In addition, the interviewer needs to know when to let a discussion go off the “planned path” into valuable areas of discovery and when to bring a fruitless discussion back on track. The interviewer needs to have sufficient domain knowledge to know which discussions are adding value and which are sapping valuable time. He or she also needs to know what follow-up questions to ask on the fly to get the details the team needs to make product decisions.

We cannot stress enough how important it is for interviewers to be well-trained and experienced. Without this, interviewers can unknowingly introduce bias into the questions they ask. This will cause participants to provide unrepresentative answers or to misinterpret the questions. Either way, the data you receive are inaccurate and should not be used. People new to interviewing may wish to take an interviewing workshop—in addition to reading this chapter—to better internalize the information. Another way to gain experience is to offer to serve as the notetaker for an experienced interviewer. We are always looking for an eager notetaker to help out, and you will get the opportunity to see how we handle various situations that arise.

We strongly recommend finding someone who is a skilled interviewer and asking him or her to review your questions. Then, practice interviewing him or her, and ask specifically for feedback on anything you may do that introduces bias. The more you practice this skill, the better you will become and the more confident you can be in the accuracy of the data you obtain. Co-interviewing with a skilled interviewer is always helpful.

Finally, although we all hate to watch ourselves on video or listen to audio of ourself, it is very helpful to watch/listen to yourself after an interview. Even experienced interviewers fall into bad habits—watching yourself on video can make you aware of them and help break them. Having an experienced interviewer watching or listening with you helps because he or she can point out areas for improvement. If you involve other members of the team, such as product managers, they may also be able to point out additional topics of interest or request that you focus on areas of concern. Ideally, this can be a fun, informative team-building activity.

The Notetaker

You may find it useful to have a colleague in the same room or another room who is taking notes for you. This frees you from having to take detailed notes. Instead, you can focus more of your attention on the interviewee’s body language and cues for following up. Depending on the situation, the notetaker may also act as a “second brain” who can suggest questions the primary interviewer might not think of in context (see Chapter 7, “Recording and Notetaking” section on page 171, for more details on capturing the data.)

The Videographer

Whenever possible, video record your interview session (see Chapter 7, “Recording and Notetaking” section on page 171 for a detailed discussion of the benefits of video recording). You will need someone to be responsible for making the recording. In most cases, this person simply needs to start and stop the recording, insert new storage devices (e.g., SD cards) as needed, and keep an eye out for any technical issues that arise. He or she can also watch audio and light levels of the recording and suggest changes as needed. Be sure to practice with the videographer in advance. Losing data because of a video error is a common, yet entirely preventable, occurrence.

Inviting Observers

As with other user research techniques, we do not recommend having observers (e.g., colleagues, product team members) in the same room as the participant during the interview. If you do not have the facilities to allow someone to observe the interviews from another room but you do want stakeholders to be present, it is best to limit the observers to one or two individuals. Any more than this will intimidate the person being interviewed. The observers should be told explicitly, prior to the session, not to interrupt the interview at any time.

It is up to you if you would like to invite observers to suggest questions for the participants. All questions observers suggest should follow the same guidelines discussed above (e.g., avoid bias, keep them brief). Since you cannot control what the observers say, we recommend asking them to write questions on paper and then pass them to you at the end of the session. This works well in cases where you do not have the domain knowledge to ask and follow up on technical questions. You then have the opportunity to reword a loaded or double-barreled question. Or you can work with the observers prior to the session to devise a set of follow-up questions that they may ask if time permits. You may also permit observers to view a session remotely and use a chat feature to suggest questions to you in real time. However, this can be difficult to manage since it requires you to keep an eye on the chat feature, be able to figure out the appropriate moment during the interview to ask the question, reword it on the fly, and know when to skip asking a suggested question.

Activity Materials

You will need the following materials for an interview (the use of these will be discussed in more detail in the next section):

■ List of questions for interview

■ Method of notetaking (laptop and/or paper and pencil on clipboard)

■ Method of recording (video or audio recorder)

■ Comfortable location for participant, interviewer, notetaker, and video equipment

■ Memory aids (e.g., calendar) (optional)

■ Artifacts to show the participant (optional)

Conducting an Interview

Things to Be Aware of When Conducting Interviews

As with all user research activities, there are some factors that you should be aware of before you jump into the activity. In the case of interviews, these include bias and honesty.

Bias

It is easy to introduce bias into an interview. Choice of words, your way speaking, and body language can all introduce bias. Bias unfairly influences participants to answer in a way that does not accurately reflect their true feelings. Your job as an interviewer is to put aside your ideas, feelings, thoughts, and hopes about a topic and elicit those things from the participant. A skilled interviewer will word, ask, and respond to questions in a way that encourages a participant to answer truthfully and without worry of being judged. This takes practice and lots of it.

Honesty

Individuals who are hooked on performance metrics or who question the value of “anecdotal” data may frown upon interviews. Sometimes, people ask how you know a participant is telling the truth. The answer is that people are innately honest. It is an extremely rare case that a participant comes into your interview with the intention of lying to you or not providing the details you seek.

However, there are factors that can influence a participant’s desire to be completely forthcoming. Participants may provide a response that they believe is socially desirable or more acceptable rather than the truth. This is known as social desirability. Similarly, a participant may describe the way things are supposed to happen rather than the way things actually happen. For example, a participant may describe the process he or she uses at work according to recommended best practice, when, in actuality, the participant uses shortcuts and work-arounds because the “best practice” is too difficult to follow—but the participant does not want to reveal this. Make it clear that you need to understand the way he or she actually works. If work-arounds or shortcuts are used, it is helpful for you to understand this. And of course, remind the participant that all information is kept confidential—the employer will not receive a transcript of the interview.

A participant may also just agree to whatever the interviewer suggests in the belief that it is what the interviewer wants to hear. Additionally, a participant may want to impress the interviewer and therefore provide answers that increase his or her image. This is called prestige response bias. If you want the participant to provide a certain answer, he or she can likely pick up on that and oblige you. You can address these issues by being completely honest with yourself about your stake in the interview. If you understand that you have a stake in the interview and/or what your personal biases are, you can control them when writing questions. You can also word questions (see “Write the Questions” section, page 225) and respond to participants in ways that can help mitigate these issues (e.g., do not pass judgment, do not invoke authority figures). You should be a neutral evaluator at all times and encourage the participant to be completely honest with you. Be careful about raising sensitive or highly personal topics. A survey can be a better option than interviews if you are seeking information on sensitive topics. Surveys can be anonymous, but interviews are much more personal. Participants may not be forthcoming with information in person. On the other hand, if you are skilled at being a sympathetic listener and you are unafraid to ask questions that might be sensitive, interviews can be used. For more discussion on this topic, see “Asking the Tough Questions” section on page 242.

If the participant is not telling the complete truth, this will usually become apparent when you seek additional details. A skilled interviewer can identify the rare individual who is not being honest and disregard that data. When a participant is telling a story that is different from what actually happened, he or she will not be able to give you specific examples but will speak only in generalities.

You are now prepared to conduct an interview. In this section, we walk you through the steps.

First, Table 9.4 covers in general the sequence and timing of events to conduct an interview. It is based on a one-hour session and will obviously need to be adjusted for shorter or longer sessions. These are approximate times based on our personal experience and should be used only as a guide.

Table 9.4

Timeline for a one-hour interview (approximate times)

| Approximate duration | Procedure |

| 5-10 minutes | Introduction (welcome participant, complete forms, and give instructions) |

| 3-5 minutes | Warm-up (easy, nonthreatening questions) |

| 30-45 minutes | Body of the session (detailed questions) |

| This will vary depending on the number of questions | |

| 5-10 minutes | Cooling-off (summarize interview; easy questions) |

| 5 minutes | Wrap-up (thank participant and escort him or her out) |

Interviewing is a skill and takes practice. You should observe the five phases of an interview and monitor the interviewing relationship throughout.

The Five Phases of an Interview

Whether the interview lasts ten minutes or two hours, a good interview is conducted in phases. There are five main phases to be familiar with.

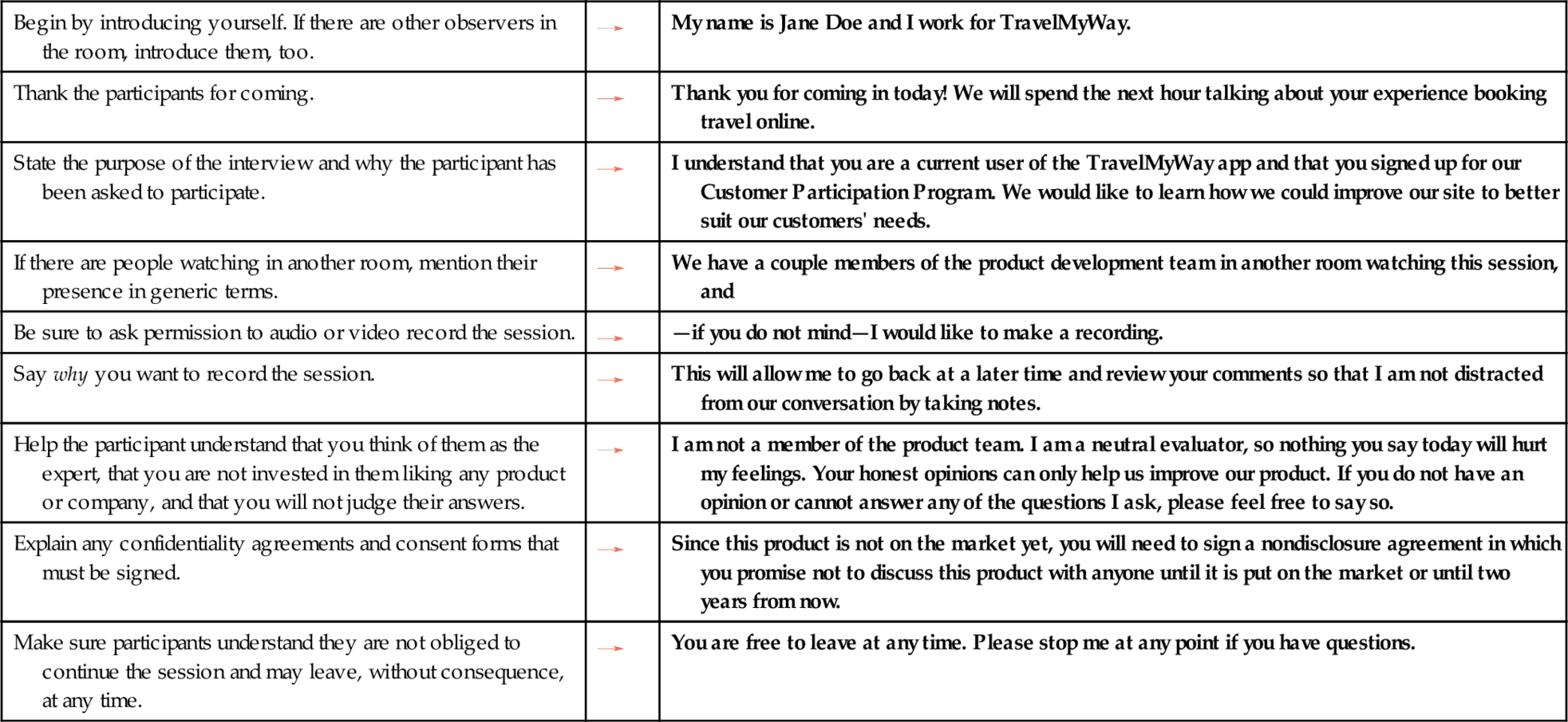

The Introduction

This should not be too long. If it is over ten minutes, you are probably giving the participant too many instructions and other things to remember. This is the first opportunity you have to encourage participants to answer honestly and feel free to say when they cannot answer one of your questions. The following is a sample introduction:

| Begin by introducing yourself. If there are other observers in the room, introduce them, too. | My name is Jane Doe and I work for TravelMyWay. | |

| Thank the participants for coming. | Thank you for coming in today! We will spend the next hour talking about your experience booking travel online. | |

| State the purpose of the interview and why the participant has been asked to participate. | I understand that you are a current user of the TravelMyWay app and that you signed up for our Customer Participation Program. We would like to learn how we could improve our site to better suit our customers' needs. | |

| If there are people watching in another room, mention their presence in generic terms. | We have a couple members of the product development team in another room watching this session, and | |

| Be sure to ask permission to audio or video record the session. | —if you do not mind—I would like to make a recording. | |

| Say why you want to record the session. | This will allow me to go back at a later time and review your comments so that I am not distracted from our conversation by taking notes. | |

| Help the participant understand that you think of them as the expert, that you are not invested in them liking any product or company, and that you will not judge their answers. | I am not a member of the product team. I am a neutral evaluator, so nothing you say today will hurt my feelings. Your honest opinions can only help us improve our product. If you do not have an opinion or cannot answer any of the questions I ask, please feel free to say so. | |

| Explain any confidentiality agreements and consent forms that must be signed. | Since this product is not on the market yet, you will need to sign a nondisclosure agreement in which you promise not to discuss this product with anyone until it is put on the market or until two years from now. | |

| Make sure participants understand they are not obliged to continue the session and may leave, without consequence, at any time. | You are free to leave at any time. Please stop me at any point if you have questions. |

Warm-Up

Always start an interview with easy, nonthreatening questions where you are sure you will get positive answers to ease the participant into the interview. You can confirm demographic information (e.g., occupation, company), how the participant first discovered your product, etc. You may even allow the participant to vent his or her top five likes and dislikes of your product. The participant should focus his or her thoughts on your product and forget about work, traffic, the video cameras, and so on. This is best done with easy questions that feel more like a conversation and less like a verbal survey or test. It is best to avoid asking seemingly innocuous questions like “Do you enjoy working here?” or “Tell me about a recent problem you had.” Negative questions or ones that might elicit a negative response tend to taint the rest of the interview.

Five to ten minutes may be sufficient for the warm-up, but if the participant is still clearly uncomfortable, this could be longer. However, do not waste the participant’s time (and yours) with useless small talk. The warm-up should still be focused on the topic of the interview.

Body of the Session

Here is the place where you should ask the questions you wrote and tested (see “Write the Questions” section, page 225 and “Test Your Questions” section, page 233). Present questions in a logical manner (e.g., chronological), beginning with general questions and move into more detailed ones. Avoid haphazardly jumping from one topic to another. This should be the bulk (about 80%) of your interview time with the participant.

Cooling-Off

Your interview may have been intense with very detailed questions. At this point, you may want to pull back and ask more general questions or summarize the interview. Ask any follow-up questions in light of the entire interview. One cool-off question we like in particular is “Is there anything else I should have asked you about?” This is a great trick that will often pivot an entire interview.

Wrap-Up

You should demonstrate that the interview is now at a close. This is a good time to ask the participant whether there are any questions for you. Some people like to do this by closing a notebook and putting away their pen (if they were taking notes), changing their seat position, or turning off the audio and/or video recorder. Thank the person for his or her time.

Your Role as the Interviewer

Think of your job as an interviewer as a coach that helps participants provide the information you need. “Active listening” means that you must judge if each response has adequately addressed your question, be on the lookout for areas of deeper exploration, and monitor the interviewing relationship throughout. Interviewing is an active process because you know the information you are seeking and must coax that information from the participant. Because of this, interviewing can be an intense activity for the interviewer.

Keep on Track

It is easy for unstructured interviews to go off track. The participant may go into far more detail than you need but not know that. A participant may also digress to topics that are outside the scope of the study. It is your job to keep the participant focused on the topic at hand and move on to the next topic when you have the information needed. Below are some polite comments to get participants back on track or to move them on to a new topic:

I can tell that you have a lot of detail to provide about this, but because of our time constraints, I need to move on to a new topic. If we have time at the end, I would like to come back to this discussion.

That’s really interesting. I was wondering if we could go back to topic XYZ for a moment …

I’m sorry to stop you, but a moment ago, you were discussing XYZ. Can you tell me more about that?

Silence Is Golden

One of the most difficult skills in interviewing is patience. You never want to complete participants’ thoughts for them or put words in their mouths. Give each participant time to complete his or her thoughts. If you do not have enough information after adequate silence, then follow up with another question or restate the participant’s answer (see “Reflecting” section, page 248). Of course, if the participant is struggling with a word and you are sure you know what the participant is trying to say, offer the word or phrase the participant is searching for, especially if the participant says, “It’s on the tip of my tongue. Do you know what I’m talking about?”

Think of silence as a tool in your tool belt. An interviewee may wonder how much detail you are looking for in response to a question. In that case, he or she will likely provide a brief answer and then wait to see whether you move on. If you do not, the participant has been “given permission” to provide more detail. Counting to five before either moving on to the next question or probing for more details can provide adequate time for the participant to continue. Counting to ten can seem uncomfortable to both you and the participant but can be a useful method for coaxing a response from a reticent interviewee. Always pay attention to the participant’s body language (e.g., sitting forward, poised to make another statement) to determine whether he or she has more to say.

It is possible to go too far with your pauses and risk giving participants the silent treatment. That is why acknowledgment tokens are so important. Acknowledgment tokens are words like “oh,” “ah,” “mm hm,” and “uh huh” that carry no content. Since they are free of content, they are unobtrusive and require almost no processing by the participant, so he or she can continue unimpeded with a train of thought. These devices reassure participants that you hear them, understand what is being said, and want them to continue. Speakers expect a reaction from listeners, so acknowledgment tokens complete the “conversational loop” and keep the interviewing relationship a partnership, rather than a one-way dialog. Tokens like “mm hm” and “uh huh” are called “continuers” because they are not intrusive or directive. Tokens like “OK” and “yeah” imply agreement, which you may not want to imply to participants, revealing your personal opinions (Boren & Ramey, 2000). However, this varies hugely from culture to culture. For example, in Japanese, if an interviewer failed to say “hai” (yes) often, it would be considered very rude.

Remain Attentive

Have you had the experience where someone has been talking for the past several minutes and you have no idea what he or she has been saying? If you are tired or bored, it is easy to zone out. Obviously, this is a faux pas in any conversation but particularly problematic in an interview. If you are tired or bored, there is a good chance that the participant is, too.

Take a break at a logical stopping point. This will give you a chance to walk around and wake up. Evaluate how much you have engaged the participant in the interview. If this is an unstructured interview, you should be engaging the participant frequently for clarification, examples, and reflection. If it is a highly structured interview, the interviewee’s answers should be short, followed by your next question. In either case, you should be engaging in the interview (without interrupting the participant, of course). After the break, take a moment to ask the interviewee to briefly summarize his or her last response. This will help the interview pick up where it left off and get you back on track.

If you have conducted several interviews on the same topic before, it is easy to assume that you have heard it all. What new information could the sixth participant provide? If you think you already know the answers to the questions, you can find yourself hearing what you want to hear or expect to hear, thereby missing new information. Every participant has something unique to provide—although it may not be significant enough to warrant additional interviews. If you have conducted several interviews and feel confident that you have gained the required information, do not recruit additional participants. However, once the participant is in the door, you owe him or her the same attention that you gave the very first participant. Keep an open mind and you will be surprised at what you can learn.

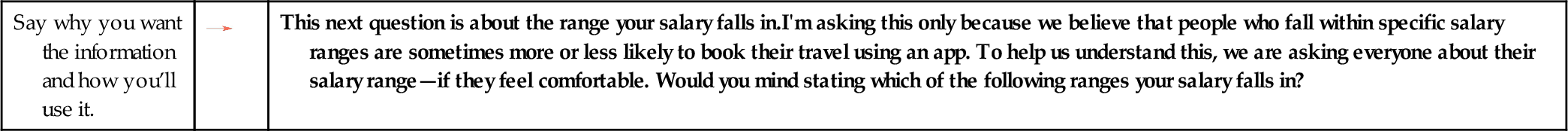

Asking the Tough Questions

To help determine if your questions are sensitive or embarrassing, run your questions by someone not connected with your project. Sometimes, you may need to ask questions that are embarrassing or cover sensitive topics. As we mentioned earlier, this may be better done via surveys, but if you think that there is a need to ask a difficult question in an interview, wait until you have developed a rapport with the participant. When you ask the question, explain why you need the information. This lets the participant know that you are asking for a legitimate reason and not just out of curiosity. The participant will be more likely to answer your question and relieve any tension. For example,

| Say why you want the information and how you’ll use it. | This next question is about the range your salary falls in. I'm asking this only because we believe that people who fall within specific salary ranges are sometimes more or less likely to book their travel using an app. To help us understand this, we are asking everyone about their salary range—if they feel comfortable. Would you mind stating which of the following ranges your salary falls in? |

Using Examples

No matter how hard you try to make your questions clear, a participant may still have difficulty understanding exactly what you are asking. Sometimes, rewording the question is not sufficient and an example is necessary for clarification. Since the example could introduce bias, you want to do this as a last resort. Having some canned examples for each question and then asking colleagues to check those examples for bias will help immensely.

Give the interviewee a moment to think about the question and attempt to answer it. If it is clear that the participant does not understand the question or asks for an example, provide one of the canned examples. If the participant still does not understand, you could either provide a second example or move to the next question.

Watch for Generalities

Interviewees will often speak in general terms because they believe it is more useful to provide summary descriptions or typical situations rather than specific examples. This is usually the result of a generalized question (see below):

If you are looking for specific, detailed answers, do not ask generalized questions. Ask for significant events. Since the best indicator of the present is the past, ask the interviewee to describe a particular past event that best exemplifies the situation. Keep in mind our earlier discussion about memory limitations and telescoping (see page 231). Below is a sample interview asking for a significant event:

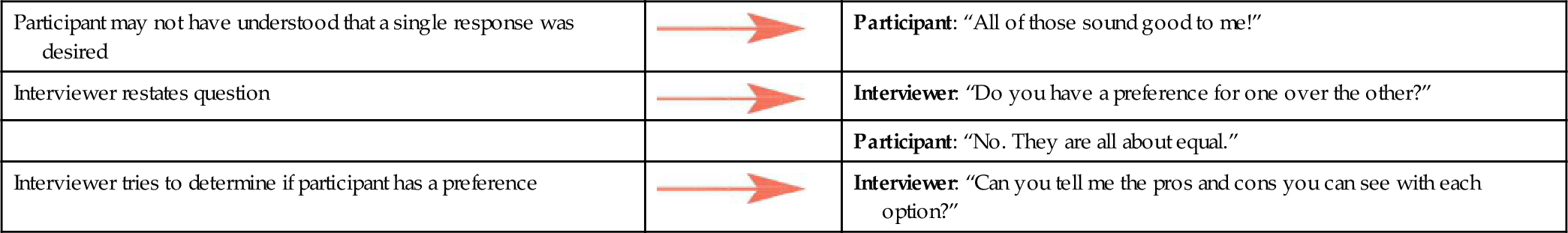

Do Not Force Choices

Do not force opinions or choices from participants. If you ask an interviewee to make a choice from a list of options but he or she says that it does not matter or all of them are fine, take this as an opportunity to learn more about what the participant thinks about each option. By asking the participant to verbalize (and therefore think more about) each option, he or she may then show more of a preference for one option over others or at least help you understand why he or she feels the way he or she does. If the participant states that all options are equal, do not force him or her to make a choice. Likewise, if the participant states that he or she does not have an opinion on something, forcing him or her to elaborate will only generate annoyance (see example below).

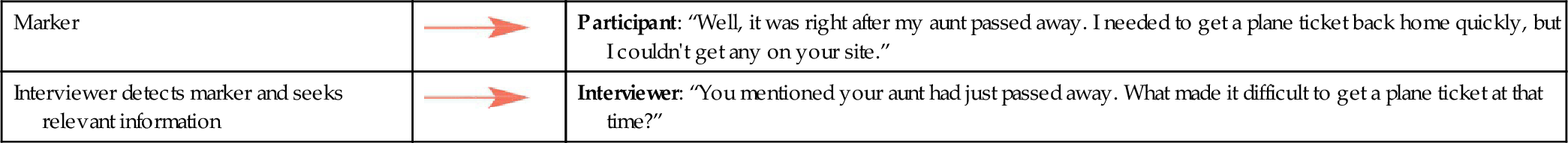

Watch for Markers

Sometimes, participants throw out markers. These are key events to the participant that you can probe into for more rich information. You should search for more details only if you believe it will provide relevant detail to your study—and not out of curiosity. Below is an interview excerpt with a marker and appropriate follow-up:

The participant provided the marker of her aunt passing away. That was critical to her. She was stressed out and could not find the information she needed. She wanted someone to personally help her and provide some support, but the app could not do it. Consequently, she now has a strong negative memory of the TravelMyWay app and a positive one of the competitor. Following up on that marker allows us to better understand the context of what happened and why the experience was so difficult for the participant. If the participant drops such a marker inadvertently and does not feel comfortable elaborating on it, he or she will let you know the topic is off-limits.

Select the Right Types of Probe

Probes are questions used to get interviewees to clarify or elaborate on responses. Your probes for detail should be as unbiased as your initial question to the participant. There are closed-ended and open-ended probes, just like the initial question you asked. A closed-ended probe would be something like “Were you using Chrome or Safari?” An open-ended probe might be “Tell me about the browser(s) you use.” Keep all probes neutral and do not ask the participant to defend his or her choices.

Table 9.5 provides an excellent comparison of different types of biased and unbiased probes and what makes each probe biased.

Table 9.5

Biased and unbiased probes

| Ask | Instead of | Why |

| Can you tell me what you are thinking right now? What are you trying to do? | Are you thinking _____? Are you trying to _____? | Even though you may think you know what they are thinking, your job is to get them to say it. Also, you do not want to put words into their mouths, because you may be wrong. |

| What are you thinking? Can you explain to me what you are trying to do? | Why are you _____? Are you trying to _____ because _____? | By asking participants why they are doing something, they may feel that you are asking them to justify their actions and, therefore, think that they are going about the task incorrectly. |

| Can you explain to me your train of thought right now? (After the task is ended) Why did you try to _____? | Are you trying to_____? | It is, however, acceptable to ask participants why they went about a task in a certain way after the task has been ended or at the end of the test if future tasks have components similar to the task you are questioning them about. |

| Did you find the product easy or difficult to use? Were the instructions clear or confusing? Were error messages helpful or hindering? | Did you find the product easy to use? Did you find the product difficult to use? Were the error messages helpful? | Trying to get someone to express an opinion on a specific usability attribute is not always easy. Therefore, you may find that you need to guide participants by specifying the attribute you want them to react to. It is important to use both ends of the spectrum when you do this so that they do not perceive you as encouraging either a positive or negative answer. Also, by doing so, you will encourage a more informative response. Instead of responding “No (it was not easy),” they are more likely to say “I found it very difficult to use,” or “It was pretty easy.” You then can follow up by asking them “Why?” |

| What are you feeling? How did you feel when you were doing _____? | Are you feeling confused? Are you feeling frustrated? | Sometimes, participants need to stop and think. Though they may appear confused or frustrated, they may just be contemplating. Do not risk inserting your guess about how they are feeling. |

| Would you change anything about this (product, screen, design, etc.)? | Do you think_____ would improve the product? | Unless the design team is considering a particular design change, you should never suggest what changes participants should talk about. |

| Are there any changes you would make to_____ to make it easier to use? | If we changed _____to_____, do you think that it would be easier to use? | If there is a design change that the design team wants to explore specifically, ask the participants to react to it after they have made their initial suggestions. |

(adapted from Dumas & Redish, 1999)

Some interviewers use the strategy of “playing dumb” to get more detail out of participants. By downplaying what you know, participants will be more explicit and may want to impress you with their knowledge. This may work in some cases, but if you slip and reveal in a question or probe that you know more than you are letting on, the participant can feel betrayed, duped, or patronized. This will clearly harm the interviewing relationship. As a result, we recommend being honest about what you know and understand while making it clear that your knowledge is limited and that the participant is there to increase your knowledge.

In that sense, adopting a beginner’s mind and asking naive questions will help you be more open to what your participants have to say and instill confidence in them that they are the experts, not you.

Watch Your Body Language

Your tone and body language can affect the way a participant perceives your questions. Be alert to your biases. Is there an answer to your question that you would like the participant to provide? Is there an answer you expect? Your expectations and preferences can be conveyed in your tone, body language, and the way you phrase questions, probes, and summaries. For example, looking bored or not making eye contact when you disagree or sitting on the edge of your seat and nodding vigorously when the participant is confirming your suspicions will clearly reveal your biases. Your biases are even conveyed in the responses that you do not follow up on. Watching yourself on video can help you identify those biases. If you are alert to your biases, you can better control them. You can also use your body language to “hack your body for better interviews” (see http://www.gv.com/lib/how-to-hack-your-body-language-for-better-interviews for an overview).

Know When to Move On

Knowing when to let go is as important as knowing when to follow up. A participant may not be as forthcoming as you would like, or maybe, the person is just plainly lying. As rare as that is, you should know how and when to move on. Remember: this is an interview, not an interrogation. Even if you suspect that the participant is not being completely honest, continued badgering is as rude as calling the participant a liar. Once it is clear that the participant cannot provide the details you are looking for, drop the line of questioning and move on. If necessary, you can throw out that participant’s data later. For ethical reasons, you must remember to treat the participant with respect, and part of that is knowing when to let a topic of discussion drop.

Reflecting

To verify that you understand what the participant has told you, it is essential to summarize, reword, or reflect the participant’s responses. You are not probing for more details but confirming the detail you already have. It is not necessary to do this after every response, especially if the response is brief and straightforward as in structured interviews. However, if the participant’s response has been lengthy, detailed, or not completely clear, you should summarize and restate what the participant has said to check for accuracy. A reflection of the earlier interview excerpt (see page 245) is provided below:

I just want to make sure that I have captured your experience correctly. You needed to purchase tickets for immediate travel, and you were looking for a bereavement discount. You couldn’t find information on bereavement discounts or an agent to assist you using the TravelMyWay app, so you used the TravelTravel app because you knew they had an agent on call. They were then able to get you the tickets at a discount. Does that summarize your experience correctly?

Reflections help build rapport by demonstrating that you were listening and understood the participant’s comments. They can also be used to search for more information. The participant may clarify any incorrect information or provide additional information, when responding to your summary.

At no time should you insert analysis into your summary or in response to a participant’s statement. In other words, do not try to provide a solution to a problem the participant has had and explanations for why the product behaved as it did or why you think the participant made a certain choice. In the example above, you would not want to inform the participant where she could have found the bereavement discount on your site. You are not a counselor, and you should not be defending your product. You are there to collect information from the interviewee—nothing more. Ask for observations, not predictions or hypotheses.

Empathy and Antagonism

When you are speaking with someone—even if it is someone you barely know—doesn’t it make you feel better to know that the other person understands how you feel? A skilled interviewer is able to empathize with the participant without introducing bias. Keep in mind that this is not a conversation in the traditional sense; you are not there to contribute your own thoughts and feelings to the discussion. In the earlier example, the interviewer could have shown empathy by stating: “That [bereavement] must have been a difficult time for you.” An inappropriate response would have been: “I know exactly how you feel. When my grandmother passed away, I had to pay an arm and a leg for my plane ticket.” The interview is not about you. You do not have to be a robot, devoid of emotion, in order to prevent bias, but also know what is appropriate and what is inappropriate. Make eye contact and use your body language to show the participant that you are engaged, that you understand what he or she is saying, and that you accept the participant regardless of what he or she has said.

Transitions

Your questions or topics for discussion should transition smoothly from one topic to another. This will allow participants to continue on a track of thought, and the conversation will appear more natural. If you must change to a new topic of discussion and there is not a smooth transition, you can state: “That’s excellent information you’ve given me. While I make a note of it, can you think about how you would < introduce different topic > ?” This lets the participant know that he or she should not be looking for a connection or follow-up from the last question. If the participant believes that you are trying to probe more deeply into the previous topic, he or she may get confused or misinterpret your next question. A simple transition statement gives closure to the last topic and sets the stage for the next one.

Avoid negative connectors like “but” and “however.” These might signal to a participant that he or she has spoken too long or has said something incorrect. The person is likely to be more cautious when answering the following questions.

Monitoring the Relationship with the Interviewee

Like all user research activities, interviews are a giving and taking of information. Since it is one-on-one, the relationship is more personal. To get the most out of participants, it is important to monitor the relationship and treat the participant ethically. You want to make sure that the participant is comfortable, engaged, and trusting. If the participant does not feel you are being honest or is wondering what the motivation is behind your questions, he or she will be guarded and will not provide the full details you are looking for.

Watch the Participant’s Body Language

Does the participant seem tense, nervous, bored, or angry? Is he or she looking at the clock or is his or her attention lapsing? Do you feel tense? If so, the participant likely feels tense too. You may have jumped into the detailed, difficult, or sensitive questions before you established a good rapport. If possible, go back to easier questions, establish the purpose and motivations of the study, and be sure that the participant is a willing partner in the activity. If a particular line of questioning is the problem, it is best to abandon those questions and move on. A break may help. Sometimes, a participant is just having a bad day and nothing you say or do will help. At that point, ending the interview can be the kindest act possible for the both of you.

Fighting for Control

If you find yourself competing with the participant for control of the interview, ask yourself why. Is the participant refusing to answer the questions you are asking or is he or she interrupting before you can complete your questions? Just as the interview is not about your thoughts or opinions, it is not up to the participant to ask the questions or drive the interview. At some point, the participant misunderstood the guidelines of the relationship. Begin with polite attempts to regain control, such as the following:

Because we have a limited amount of time and there are several topics that I would like to cover with you, I am going to need to limit the amount of time we can discuss each topic.

If the participant refuses to be a cooperative partner in the interviewing relationship and you do not feel you are obtaining useful information, simply let the participant go on and then write off the data. In extreme cases, it is best for all parties to end the interview early. If you have recorded the session, watch or listen to it with a colleague to see whether you can identify where the interviewing relationship went awry and how you can avoid it in the future. Think of this as a learning opportunity where you can practice and improve your conversational control skills.

Hold Your Opinions

Even though the interview is not about you, if the participant directly asks your opinion or asks you a question, you do not want to seem evasive because it could harm the rapport you have established. If you believe your response could bias the participant’s future responses, your reply should be straightforward:

Actually, I don’t want to bias your responses so I can’t discuss that right now. I really want to hear your honest thoughts. I would be happy to talk about my experiences after the interview.

If you are sure that the question and your response will not have an effect on the remainder of the interview, you can answer the question, but keep it brief.

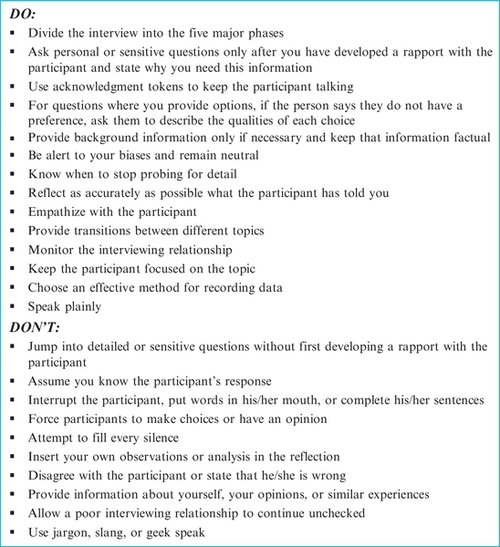

Dos and Don’ts

We have provided many recommendations about how to conduct a successful interview. It takes a lot of sessions and being in a lot of different scenarios to be a good interviewer. Do not get discouraged. For easy referral, some of the key tips are summarized in Figure 9.4.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Depending on the purpose of and outlet for your interviews, either you can wait until you have conducted all the interviews before analyzing the data, or you can do preliminary analysis following each interview. For UX professionals, we recommend the latter because it can give you insights for future interviews. You may want to delve into more detail on questions or remove questions that are not providing value. And as any UX professional can attest to, stakeholders often ask for results before a study is complete. It can help if you have something more substantial to give them than just a few interesting quotes that stand out in your mind. On the other hand, for some academic studies, conducting all the interviews prior to data analysis may be more appropriate because it increases standardization across interviews, which is often necessary for scientific publication.

As with any activity, the longer you wait to get to the analysis, the less you will remember about the session. The notes will be more difficult to interpret, and you will have to rely heavily on the recordings. The more you have to rely on the recordings, the more time it will take you to analyze the data. Either way, hold a debrief session as soon as possible with your notetaker and any other observers to discuss what you learned. Review the recording to fill in any gaps or expand on ideas if necessary, and add any additional notes or quotes. If the session is still fresh in your mind, it will not take as long to review the recording.

Transcription

For some interview studies, you may want to have the audio recordings transcribed into text (e.g., if it is critical to have the exact words your participant uses recorded, if you want to publish your findings in some scientific venues). Transcription is typically done in one of three ways: verbatim, edited, or summarized. Verbatim transcripts capture a record of exactly what was done by both the interviewer and respondent including “ums,” “ahs,” and misstatements. For some types of analysis (e.g., linguistic analysis), these word crutches are important. When such detail is not necessary, you may choose an edited or summarized transcript. Edited transcripts typically do not include word crutches or misstatements. Summarized transcripts typically contain an edited and condensed version of the questions asked or topics raised by the interviewer since these are known in advance, along with the respondent’s comments.

Depending on whether you conducted a structured, semi-structured, or unstructured interview, you will have different types of data to analyze.

Structured Data

If you are conducting structured or semi-structured interviews, begin by tallying the responses to closed-ended questions. For example, how many people so far have selected each option in a multiple-choice question or what is the average rating given in a Likert scale question? Structured data from an interview are equivalent to survey data, with the exception that you may have to refer to recordings rather than data from paper or online forms. Chapter 10 has a detailed discussion of closed-ended question data analysis (see “Data Analysis and Interpretation” section, page 290).

Unstructured Data

Unstructured data are more time-consuming to analyze, in our experience so much so that it often goes unanalyzed. We recommend three strategies for analyzing unstructured data: categorizing and counting, affinity diagramming, and qualitative content/thematic analysis.

Categorizing and Counting

If you are conducting unstructured interviews, you can begin by identifying potential categories in the text as a whole. What is the range of responses you are getting? What is the most frequent response? Once you have identified categories, you can count the number of instances each category is represented in the data and organize this by participant or as represented in the interviews overall. After you have tallied the most frequent responses, select some illustrative quotes to represent each category of response.

Affinity Diagram

An affinity diagram is a method for analyzing interview data quickly. Similar findings or concepts are grouped together to identify themes or trends in the data. A detailed discussion of what an affinity diagram is, how to create one, and how to analyze the data from one is provided in Chapter 12 on page 340.

Qualitative Content/Thematic Analysis

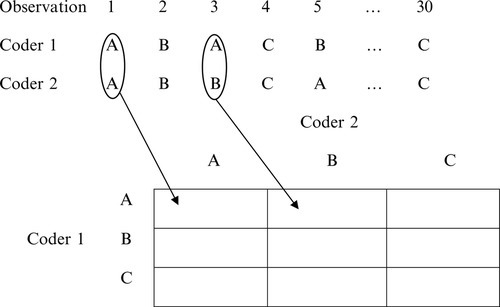

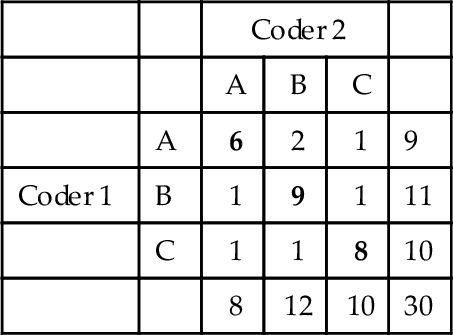

Content analysis is a method of sorting, synthesizing, and organizing unstructured textual data from an interview or other source (e.g., survey, screen scrape of online forum). Content analysis may be done manually (by hand or software-assisted) or using software alone. When done manually (by hand or software-assisted), researchers must read and reread interviewee responses, generate a scheme to categorize the answers, develop rules for assigning responses to the categories, and ensure that responses are reliably assigned to categories. Because these rules are imperfect and interpretation of interviewee responses is difficult, researchers may categorize answers differently. Therefore, to ensure that answers are reliably assigned to categories, two or more researchers must code each interview and a predetermined rate of interrater reliability (e.g., Cohen’s kappa) must be achieved (see How to Calculate Interrater Reliability [Kappa] for details).

Several tools are available for purchase to help you analyze qualitative data. They range in purpose from quantitative, focusing on counting the frequency of specific words or content, to helping you look for patterns or trends in your data. If you would like to learn more about the available tools, what they do, and where to find them, refer to Chapter 8, “Qualitative Analysis Tools” section on page 208.

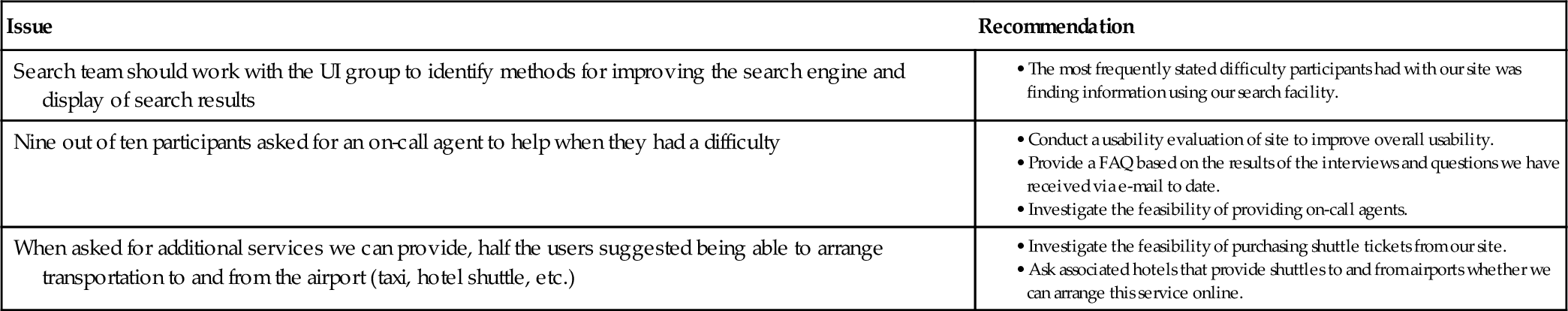

Communicating the Findings

In this section, we discuss some of the ways in which interview data can be effectively communicated. There are a few different ways that you can present the data. It all depends on the goals of your study and the method you feel best represents your data. In the end, a good report illuminates all the relevant data, provides a coherent story, and tells the stakeholders what to do next (see Table 9.6 for sample recommendations based on interview data).

Table 9.6

Sample table of recommendations

Over Time

Your interview may cover a period of time, such as asking a travel agent to describe his or her day from the first cup of coffee in the morning through turning off the computer monitor at the end of the day. Or you may ask someone a series of questions that cover the first six months of training on the job.

If your questions cover a period of time, it makes sense to analyze the data along a timeline. Use the results from your initial categorization to start filling in the timeline. In our travel agent example, what is the first thing that the majority of travel agents do in the morning? What are the activities that fill their days? Then, use individual anecdotes or details to fill in gaps and provide interesting information that does not fit neatly into a category. It can be those additional details that provide the most value.

By Topic

Your questions may not follow a timeline but simply address different topics related to a domain or user type. In these types of interviews, you may wish to analyze and present the data by question. Provide the range of answers for each question and the average response. Alternatively, you can group the data from multiple questions into larger categories and then discuss the results for each category. An affinity diagram is helpful in these types of interviews to identify higher-level categories, if they exist (see “Affinity Diagram” section, page 253).

By Participant

If each participant and his or her results are widely different, it can be difficult to categorize the data. This may be the result of difficulties with your user profile and recruiting, or it may be intentional in the case where you want to examine a variety of user types. It may make more sense to summarize the results per participant to illustrate those differences. Similarly, you may choose to analyze the data per company (customer), industry, or some other category membership.

Pulling It All Together

We began by discussing the best uses for interviews and the different types of interviews (structured, unstructured, and semi-structured). Proper wording of questions in interviews was then discussed in detail. If the questions in an interview are constructed poorly, the results of your study will be biased or will not provide the information you need. We also discussed how to conduct an interview, including the five phases of an interview, your role as an interviewer, and recording the data from the interviews. Finally, methods for analyzing the data and presenting your results were discussed.

The results from your interviews can be incorporated into documentation such as the Detailed Design Document. Ideally, additional user research techniques should be used along the way to capture new requirements and verify your current requirements. To summarize, below we list a few tips for conducting your next interview.

Interview Tips

■ Begin with general questions and follow up with specific questions. Asking specific questions first may lead the participant into talking about only what he or she thinks you want to hear about.

■ Unless using a structured interview, do not feel you need to ask every question on your list. Let the participant talk, and then, follow up with those that are most interesting for the purposes of your study.

■ Videotape everything, if possible. Audiotapes are insufficient in situations where participants constantly refer to things with vague references. Be sure to get permission from the participant before any recording (audio or video).

■ Involve your product team early and often. Encourage team members to accompany you and debrief after each visit with those who do. This will increase their buy-in to the need for research. Also, understanding what they are taking away from the interview will help you understand their priorities better.

■ Understand your own notetaking skills in deciding whether or not to type or write. Taking notes on the laptop may save a step, but slow or inaccurate typing drags down the interview. Additionally, the second step of typing up notes is a great double-check.

■ At the beginning of each recording, say the date, time, and participant number and remind the participant that you are recording the interview. For example, say, “Today is March 14th, 2015, and this is participant number 9. The red light is now on and the voice recorder is now recording.” Giving the date and participant number will help you keep track of your data and participants and help anyone who transcribes your audio data for you as well. Showing the participant a visual indicator of recording and reminding them that you are recording will provide clear information to your participant about when you are and are not recording the interview.

■ Check and recheck your equipment. For voice recorders, is the light on, indicating that it is recording? Replay sections of the recordings during breaks. If you find that audio or video was not recorded, the conversation should be fresh enough in your mind that you can jot down a few notes to fill in the blanks.