Field Studies

Introduction

Field studies refer to a broad range of data-gathering techniques conducted at the user’s location, including observation, apprenticeship, and interviewing. Collecting data in the field (i.e., in your user’s environment) is also sometimes referred to as a “site visit.” However, “site visit” is a broad term and can include other interactions with customers while not necessarily collecting data (e.g., conducting a sales demo). Other names for visits to collect data about users in their environment are “ethnographic study,” “contextual inquiry,” and “field research.”

A field study can be composed of one, a few, or several visits to the user’s environment and can be conducted in any environment in which a user lives, works, commutes, vacations, plays, visits, exercises, eats, hangs out, etc. Often, field studies are conducted in people’s homes or offices, but the right place for a field study is the place where a technology will eventually be used. For example, researchers observed users in a vineyard to develop a ubiquitous computing system for agricultural environments (Brooke & Burrell, 2003). Sounds like fun!

Depending on the goals, resources, and specific methods of the study, a field study can last on the order of minutes, hours, days, or weeks. The biggest advantage of a field study is that you get to observe users completing tasks in their environment. You can directly observe their task flows, their inefficiencies and challenges, and their delights. This information can then be used to help you discover terminology, understand unmet user needs, and see how your product can fit into the context of users’ lives.

You will notice that this chapter is designed a little differently from the other method-related chapters. In the previous chapters, we presented one primary way to conduct a specific method and then a few modifications. There is no one best way to conduct a field study—it depends on the goals of your study and your access to users. Consequently, we will provide you with several variations from which to choose. In this chapter, we discuss different types of field studies available to enable you to go into your user’s environment to collect data, how to select the best method to answer your questions, special considerations, how to analyze the data you collect, and how to present the results to stakeholders. Finally, a case study demonstrates the value of a field study “in the wild.”

Things to Be Aware of When Conducting Field Research

There are several challenges you may face when proposing a field study. There are also challenges you could face while conducting the study. Below are some specific issues to be aware of when deciding to conduct a field study.

Gaining Stakeholder Support

It can be difficult to convince people with limited time and budgets to support field studies. Products must be developed on tight budgets and deadlines. It can be easier to convince product teams or management to support an interview or usability test because the materials needed are few and the time frame for delivering results is short. It can be much more difficult to get that same support for longer-term, off-site studies with existing customers or potential end users.

However, for understanding users’ context, no short-term, lab-based study can compare to observing users in their own environment. Write a detailed proposal to demonstrate the information you plan to collect and when. Also, include estimated cost and immediate and long-term benefits. You may also want to show documented cases where products went wrong and could have been saved by conducting a field study. Better understanding of your users can also provide a competitive edge. When time is the biggest issue, you can point out that schedules slip and field studies are beneficial over time, not just in the short term. Even if you cannot get information in time to influence an upcoming release of a product, there will be future releases where your data can be used. You want your information to make an impact as soon as possible, but do not let schedules prevent you from collecting data altogether. Finally, you will likely need to educate stakeholders on the empirical nature of user research, how the information you collect on-site with users differs from lab-based data, and how the data you collect in field studies can provide a competitive edge.

Other Things to Keep in Mind

Once you have convinced stakeholders that a field study is a good idea, there are a few other things to keep in mind when designing and conducting field studies.

Types of Bias

There are two types of bias, in particular, to be aware of when conducting field studies. The first is introduced by the investigator/moderator and the second by the participant.

If the investigator is a novice to the domain, he or she may have a tendency to conceptually simplify the expert users’ problem-solving strategies while observing them. This is not done intentionally, of course, but the investigator does not have the complex mental model of the expert, so a simplification bias results. For example, if an investigator is studying database administrators and does not understand databases, he or she may think of a database as nothing more than a big spreadsheet and misinterpret (i.e., simplify) what the database administrator is explaining or demonstrating. It is important for you to be aware of this bias. One way to minimize this bias is by talking with a subject matter expert before you begin your study. He or she can help you understand the topic before you speak with users. Another way to minimize this bias is to ask users or a subject matter expert to review your notes/observations. He or she can identify areas where you have oversimplified or incorrectly captured information.

The other type of bias is called a translation bias. Expert users will attempt to translate their knowledge so that the investigator can understand it. The more the expert translates, the more potential there is for them to distort their knowledge, skills, etc. One way to avoid this is to ask the expert user to train you or speak to you as if you had just started a job working for them. If you are missing the background knowledge necessary to understand everything the user is saying, you may either ask probing questions or bring a subject matter expert (SME) with you to “translate.” However, it is to your advantage to learn as much as you can prior to your visit so that you have some background knowledge and vocabulary of what you are observing. You should be enthusiastic about learning the domain and become well-versed yourself, but with a “usability hat” on, so you can identify opportunities for improvement. This is different from coming in with preconceived notions. You should have a good base of knowledge but try not to think about solutions yet.

The Effect of Being Observed

Participants behave differently when observed; this is known as the Hawthorne effect (Landsberger, 1958). They will likely be on their best behavior (e.g., observing standard operating procedures rather than using their usual shortcuts). It can take some time for users to feel comfortable with you and reveal their “true behavior.” Users cannot keep up a façade for long, so you can expect aspects of the Hawthorne effect to diminish over time; the longer you spend observing participants and the better rapport you are able to establish with them, the lesser this effect will be.

Logistics Can Be More Challenging

Field studies can be very simple when you are conducting pure observation. All you need is a pen and paper. Depending on the location (e.g., in a public place), you may not even need anyone’s permission to observe.

However, most field studies done for product development are more complex because you are not only observing but also interacting with people (e.g., recruiter, salesperson, site contact, other observers, participants, legal departments, etc.) and because more things can potentially go wrong on-site (e.g., broken equipment, missing forms, late arrival, dead batteries). For these reasons, field studies are much more challenging (but also more rewarding!) to conduct than most other techniques described in this book. Even though your equipment may fail in the lab, you are in a better position to replace/repair it than when you are traveling to an unfamiliar location. You cannot possibly take duplicates of every piece of equipment. In addition, directions to your site may be poor and driving in unfamiliar areas can be stressful. Being detail-oriented, creating a well-thought-out plan in advance, and piloting everything can help you avoid many problems, but there will always be some surprises along the way.

Field Study Methods

While field studies are conducted in many different disciplines ranging from biology to economics, the field study methods most widely used in user research communities come to us from anthropology and are sometimes called “ethnographic studies.” However, even within the user research community, there is debate about what constitutes “ethnography” versus a “field study.” For an introduction to the debate, see the “Field Study Versus Ethnography” callout. Generally, classic ethnographic practice requires one to enter a situation with an open mind, a nonegocentric perspective, no preconceived notions or biases, and no focus on solutions. You begin by observing the user, the tasks, and the environment before you ever formulate your first question or study goal.

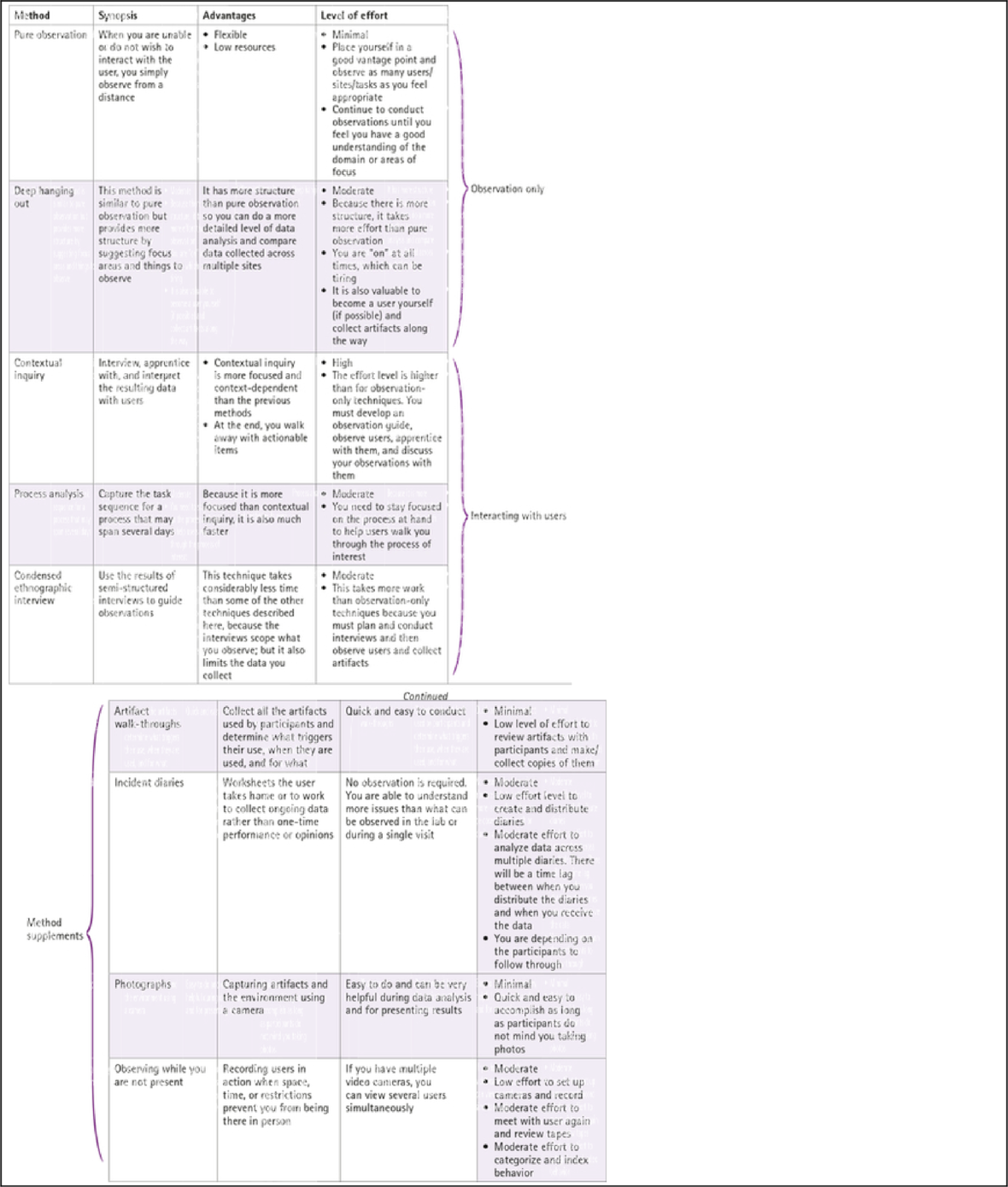

Before you can begin preparing for a field study, you need to understand the techniques available to you. Methods range from pure observation to becoming a user yourself. Table 13.1 provides a comparison between the techniques.

Since there is no standard method, we will consider a range of techniques. The goal of each method is the same: to observe users and collect information about their tasks and the context in which they are done. The cost for each method is also very similar (e.g., your time to collect and analyze the data, recording equipment, potential recruitment fees, and incentives). The differences arise in the way you collect data and some of the information you are able to collect.

The techniques described here are divided into three categories: observation only, interacting with the user, and method supplements. The most important thing to remember when designing a field study is to be flexible. Select the method(s) that will best address the goals of your study and the time and resources available to conduct it. Collect several types of data (e.g., notes, audio, video, still pictures, artifacts, sketches, diaries) to obtain a richer data set. Finally, and regardless of the type of study you conduct, do not focus on solutions before or during data collection. Doing that may bias your observations and needlessly limit the information you collect. You can conduct follow-up visits to investigate hypotheses, but—at least in the initial visit—focus on the data collection and keep an open mind.

Observation Only

Techniques that do not involve interacting with users are ideal in situations when you cannot interact with participants because doing so would take attention away from a critically important primary task (e.g., a doctor in surgery, a trader on the stock exchange floor). Observation-only techniques have their limits in terms of the information that can be collected, but they are typically less resource-intensive.

Pure Observation

The pure observation technique is valuable in situations where you cannot interact with the users. Perhaps you cannot speak with the end user for privacy or legal reasons (e.g., hospital patients), or it is an environment where you cannot distract the user with questions (e.g., emergency room doctors). In pure observation studies, users may or may not know they are being studied. If you wanted to observe people’s initial reaction to a self-serve kiosk at an airport, you might sit quietly at a well-positioned table and simply record the number of people who saw the kiosk, looked at it, and then used it. You might also capture information such as facial expressions and overheard comments. If you do not need photographs or video recordings and you are in a public place and it is ethically appropriate, you may not necessarily need to inform participants of your presence. In most situations, however, you will need to inform individuals that you are observing them (e.g., in office settings). Refer to Chapter 3 on page 66 for information about informed consent and appropriate behavior with participants.

Obviously, with this technique, you do not interact with the participant. You do not distribute surveys, interview the user, or ask for artifacts from the user. This technique is simply about immersing yourself in the environment and developing questions along the way. From here, you may go back to your product team and management to recommend additional areas of focus.

If you are new to observing people, the following things to consider may help you:

■ What language and terminology do people use?

■ If you are observing the use of an existing system, how much of the system/software/features do users actually use?

■ What barriers or stop points do people encounter?

■ If what you are interested in is task-focused:

![]() How much time do people devote to accomplishing a task?

How much time do people devote to accomplishing a task?

![]() What questions do people have to ask to accomplish a task?

What questions do people have to ask to accomplish a task?

![]() What tools do users interact with as they are trying to accomplish a task?

What tools do users interact with as they are trying to accomplish a task?

Because you do not interact with participants during pure observation, the information that you can obtain is obviously limited. You are not able to follow up on an interesting observation with a question that may help you understand why a participant engaged in a certain action. This is particularly challenging in situations where you are new to the domain and you may not understand much of what you are seeing. In addition, you cannot influence events; you get only what is presented and may miss important events as a result. Consequently, it is essential to have a good sampling plan. The sampling plan should include days/times you anticipate key events (e.g., the day before Thanksgiving Day or bad weather at an airport) and “normal” days. However, regardless of how good your sampling plan is, you may still miss infrequent but important events (e.g., a bad weather closure at the airport or multiple traumas in the ER). Nevertheless, the information that you can obtain is worthwhile and will bring you closer to understanding the user, tasks, and environment than you were when you began. As Yogi Berra said, “You can see a lot just by watching.”

Deep Hanging Out

Cartoon by Abi Jones

A more structured form of observation is referred to as “deep hanging out.” The key differences between deep hanging out and pure observation are that in deep hanging out, (1) you become a user yourself, and (2) there is a formal structure that organizes the observation process. Researchers from Intel developed this method by applying anthropological techniques to field research (Teague & Bell, 2001). Their method of deep hanging out includes structured observation, collection of artifacts, and becoming a user (i.e., in the travel example, you would actually travel and use the app yourself). However, you do not interview participants, distribute surveys, or present design ideas for feedback.

To make this data collection manageable, the system/environment is divided into ten focus areas, as shown in Table 13.2. The foci are intended to help you think about different aspects of the environment. Because these foci are standardized, you can compare data across multiple sites in a structured manner (to be described in detail later).

Table 13.2

Focal points for deep hanging out (Teague & Bell, 2001)

| Focal point | Some questions to ask |

| Family and kids | Do you see families? How many children are there? What are the age ranges? What is the interaction between the kids? Between the parents and the kids? How are they dressed? Is the environment designed to support families/kids (e.g., special activities, special locations, etc.)? |

| Food and drinks | Are food and drinks available? What is being served/consumed? Where is it served/consumed? When is it served? Are there special locations for it? Are people doing other things while eating? What is the service like? Are only certain people consuming food and drinks? |

| Built environment | How is the space laid out? What does it look like? What is the size, shape, decoration, furnishings? Is there a theme? Are there any time or space cues (e.g., clocks on the walls and windows to show time of day or orientation to the rest of the outside)? |

| Possessions | What are people carrying with them? How often do people access them? How do people carry them? What do they do with them? What are people acquiring? |

| Media consumption | What are people reading, watching, and listening to? Did they bring it with them or buy it there? Where do they consume the media and when? What do they do with it when they are done? |

| Tools and technology | What technology is built-in? How does it work? Is it for the customers or the company? Is it visible? |

| Demographics | What are the demographics of the people in the environment? Are they in groups (e.g., families, tours)? How are they dressed? How do they interact with each other? How do they behave? |

| Traffic | What is the flow of traffic through the space? Was it designed that way? What is traveling through the space (e.g., people, cars, golf carts)? Where are the high-/low-traffic areas? Why are they high-/low-traffic areas? Where do people linger? |

| Information and communication access | What are the information and communication access points (e.g., pay phones, ATMs, computer terminals, kiosks, maps, signs, guides, directories, information desks)? Do people use them, and how often? How do people use them? Where are they located (e.g., immediately visible, difficult to access)? What do they look like? |

| Overall experience | Don’t forget the forest for the trees. What is the overall environment like? What is the first and last thing you noticed? What is it like to be there? How is it similar or different from similar environments? Are there any standard behaviors, rules, or rituals? (Think high level and obtain a holistic view, rather than concentrating on details.) |

Breadth can be important, even at the expense of depth, when first learning about an area. One use of the list in Table 13.2 is to remind you to focus on a large number of areas and not focus on just one small (easy to collect) area. This list is particularly useful for a novice—to appreciate all the areas to look at and to understand that depth in every area is not that important.

Another key use of the list is to help teams who are doing research together to come away with better findings. Many times, a group of four to five people go out and conduct observations independently, but they all come back with pretty much the same findings. This can be frustrating for everyone involved and may cause stakeholders to question the value of having so many people involved in the study or the value of the study period. Using the list of foci and giving each person a specific focus area help to ensure that the team examines multiple areas. In addition, it gives individuals some direction and ownership and makes their insight a unique contribution to the team.

Numerous studies at Intel demonstrated that, regardless of the system, users, or environment they studied, these ten foci represented the domain and supported valuable data collection. The technique is intended to be flexible. There is no minimum number of foci to collect data about or recommended amount of time to spend observing each focus area. However, even if a particular focal point does not seem appropriate to your study, you should still try to collect information about it. The lack of information about that particular focal point can be just as enlightening! For example, you may think that the “family and kids” focal point is not appropriate when you are studying users in their office environment. Who brings their family to work with them? But, you may observe that a participant is constantly getting calls from a spouse and messages from the kids. Perhaps, they are complaining because your participant is never home or is late for the daughter’s recital. Maybe this means that the participant is so overwhelmed with work that problems with the family life are spilling over into work, and vice versa. Even if you do not think a particular focal point is applicable to your study, go in with an open mind and expect to be surprised.

Just as with pure observation when creating your sampling plan, we recommend collecting data at different times during the day and on different days of the week. For example, you would likely observe different things if you went to the airport at 8 am on Monday, 8 am on Saturday, and 6 pm on Wednesday.

Deep hanging out stresses that you are “on” at all times. Using our earlier travel example, you would begin your observations from the time you travel to the airport. Observe the experience from the very beginning of the process, not just once you are inside the airport. Pay attention to the signs directing you to parking and passenger pickup. The intention is to obtain a holistic view of the system/environment that goes beyond contextual inquiry (discussed on page 393).

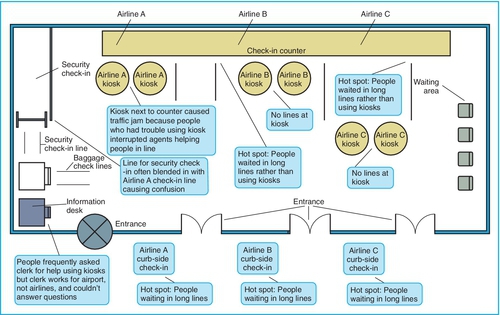

While you are observing the users and environment, create maps (see Figure 13.1). Identify where actions occur. If your focus is “family and kids,” identify locations designed for families or kids (e.g., jungle gym, family bathroom). Where do families tend to linger? In addition to creating maps, collect maps that the establishment provides. Collect every artifact you can get your hands on (e.g., objects or items that users use to complete their tasks or that result from their tasks). If allowed, take photos or videos of the environment, though keep in mind that you may need to obtain permission first.

Finally, involve yourself in the process by becoming a user. If you are interested in designing a mobile app for use at an airport, use each mobile app available for use during check-in, but never mistake yourself for the actual end user. Involving yourself in the process helps you understand what the users are experiencing, but it does not mean that you are the end user.

Interacting with the User

For actual product development (not just learning about a domain or preparing for another user research activity), it is almost always better to interact with users rather than just observe them. You will not get enough information to design from observation alone. You frequently need to follow up on an observational study with an interaction study or combine the two. Several techniques are available to you to accomplish this, including:

■ Process analysis

■ Condensed ethnographic interview

Contextual Inquiry

Beyer and Holtzblatt (1998) wrote the book on contextual inquiry (CI) and contextual design. In this chapter, we introduce you to the basics of this very popular and useful method. If this is a method you plan to use often, we highly recommend reading the book. There are four main parts to contextual inquiry:

■ Context. You must go to the user’s environment to understand the context of his or her actions. Contextual inquiry assumes that observation alone or out-of-context interviews are insufficient.

■ Partnership. To better understand the user, tasks, and environment, you should develop a master-apprentice relationship with the participant. Immerse yourself in the participant’s work and do as he or she does. Obviously, this is not possible with many jobs (e.g., surgeon, fighter pilot), so you have to be flexible.

■ Interpretation. Observations must be interpreted with the participant to be used later. Verify that your assumptions and conclusions are correct.

■ Focus. Develop an observation guide to keep you focused on the subject of interest/inquiry.

Unlike in pure observation, in contextual inquiry, the user is very aware of your presence and becomes a partner in the research. It can be faster, taking only a few hours or a day. At the end, you walk away with actionable items to begin designing a product, your next user research activity (e.g., tasks for a usability test, questions for a survey), or areas for innovation and future research.

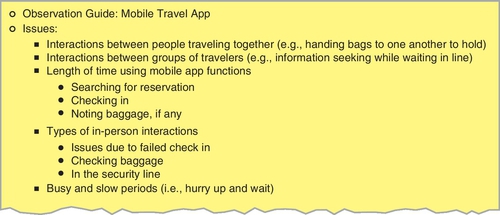

The process begins by developing an observation guide (see Figure 13.2). This is a list of general concerns or issues to guide your observations—but it is not a list of specific questions to ask. You may want to refer to the foci listed in Table 13.2 to build your observation guide. Using a mobile travel app observation example, some issues to look out for might be sources of frustration for mobile app users, points where travelers could use the app instead of a self-check-in kiosk or airline agent, points where travelers abandon using the app, and length of time spent interacting with the app. This observation guide would obviously be influenced by the goals of your study and what you want to learn.

Next, you carefully select representative users to observe and apprentice. Beyer and Holtzblatt recommend 15-20 users, but our experience is that four to six are more common in industry practice. The number of participants used should be based on the question you are trying to answer. The more focused (or narrow) the question and the more consistency across users, tasks, and environments, the fewer participants are necessary. For example, if you are interested in studying only one particular task that travelers who are “frequent fliers” engage in during a trip at one particular airport, rather than the entire airport experience for all travelers at all airports, you could observe fewer participants and feel more confident in the reliability of the results (refer “How Many Participants” section, page 402).

Context

Work with participants individually. Begin by observing the participant in action. The goal is to collect ongoing and individual data points rather than a summary or abstract description of the way the participant works. It is best to have two researchers present who can switch roles between notetaker and interviewer quickly. Often, an interviewee will have better chemistry with one researcher or the other. Having the flexibility to switch roles quickly can improve the quality of the data you collect. You can ask the participant to think aloud as he or she works (see Chapter 7, “Using a Think-Aloud Protocol” section, page 169), or you may choose to ask the participant clarifying questions along the way. You may even decide not to interrupt the participant at all but wait until he or she has completed a task and then ask your questions. Your choice should depend on the environment, task, your goals, and user.

For example, air travelers may not be able to think aloud as they go through airport security. It may also be difficult for you to observe them during this time due to restrictions on your presence and the use of recording devices in airport security areas. It is best in that case to wait until the traveler has completed the security checks to ask your questions. Task clarification questions in the case of an airport security line might include “How did you determine which line to use?” “Why did you ask the security personnel whether you could keep your shoes on?” and “How did you use the app to determine security line wait time?”

Partnership

Once the participant is comfortable with your presence and you have developed a rapport (see “Monitoring the Relationship with the Interviewee” section on page 249 in Chapter 9 to learn about developing a rapport with participants), you can introduce the master-apprentice relationship. As long as the company approves it and you have considered potential ethical and legal issues (see Chapter 3, page 66), the participant becomes the master and instructs you (the apprentice) on how to complete a given task. Despite limitations in some environments (e.g., you may not be able to join a pilot in the cockpit of a plane), the participant can always instruct you on some aspect of his or her activities (e.g., perhaps, you can sit in a flight simulator with a pilot).

It is easy for certain types of relationships to develop during this time. You should avoid the three relationships listed below because they are not conducive to unbiased data collection:

■ Expert-novice. Because you are entering the environment as a “specialist,” the user may see you as the expert. It is important for you to remind the participant that he or she is the expert and you are the novice.

■ Interviewer-interviewee. Participants may assume that this is an interview, and if you are not asking questions, you already understand everything. Stress to the participant that you are new to the domain and need to be instructed as if you were a new employee starting the job. The user should not wait for questions from you before offering information or instruction.

■ Guest-host. You are a partner with the user and should be involved with the user’s work. The user should not be getting you coffee, and you should not be concerned about invading the user’s personal space. Get in there and learn what the user knows.

Interpretation

A key aspect of contextual inquiry is to share your interpretations with participants and have them verify that your interpretations are correct. You do not have to worry that users will agree with an incorrect interpretation just to please you. When you create a solid master-apprentice relationship, the user will be keen for you to understand the process and will correct any misconceptions you have. He or she will often add to your interpretations as well, extending your knowledge and understanding beyond what you have observed.

Remember what your teacher told you: “The only dumb questions are the ones you don’t ask.” Do not be afraid to ask even simple questions; just remember to phrase them correctly (see Moderation Tips, chapter 7, Table 7.3, page 166). In addition to increasing your own knowledge, you can make the participants think more about what they would consider “standard practices” or the “that’s just the way we have always done it” mentality to help you understand the why (see “Your Role as the Interviewer” section on page 240 in Chapter 9 for tips about communicating with users and helping them provide the information you are seeking).

Focus

During the entire process, you want to keep the inquiry focused on the areas of concern. You began by developing an observation guide for the inquiry (see Figure 13.2). Refer to this guide throughout the process. Since the participant is the master, he or she will guide the conversation to points he or she finds interesting. It is essential for you to learn what the participant finds important, but it is also critical that you get the data necessary to guide your design, the next user research activity, or innovation. The user may find it more interesting to cover all topics at a high level, but your focus should uncover details in the areas that you believe are most important. Remember that the devil is in the details; if you do not uncover the details, your interpretation of the data will be inadequate to inform design, the next user research activity, or innovation (see “Your Role as the Interviewer” section on page 240 in Chapter 9 to learn more about guiding the participant’s conversation).

Process Analysis

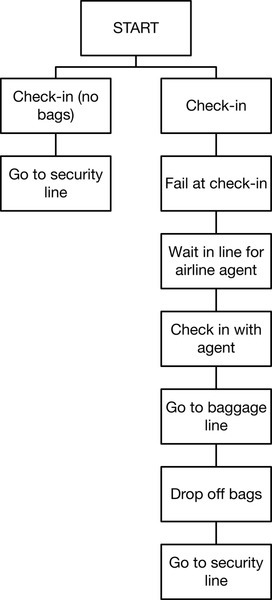

A process analysis is a focused type of field study targeted at understanding the task sequence for a process that may span several days. It is similar to contextual inquiry, but unlike a contextual inquiry, you begin the process analysis with a series of questions and you do not necessarily apprentice with the user. At the end of a process analysis, you develop a process map that visually demonstrates the steps in a process. (Figure 13.3 illustrates a very simple process map for a traveler using a mobile app.) Because process analysis is more focused than contextual inquiry, it is also much faster to conduct.

The following are questions to answer during a process analysis:

■ When does the first task in the process happen?

■ What triggers it?

■ Who does it?

■ What information does the person have when the task begins?

■ What are the major steps in the task?

■ What information comes out of it?

■ Who is the next person in the chain of the process?

■ When does the next task happen? (repeat for each task in the process)

■ How do you know when the process is complete?

■ Does this process connect to other processes?

■ Is this process ever reopened, and if so, under what circumstances?

■ What errors can be made? How serious are they? How often do they occur?

■ What are the major roadblocks to efficient performance?

Condensed Ethnographic Interview

Based on the cognitive science model of expert knowledge, the condensed ethnographic interview employs the standardization and focus of a semi-structured interview (see Chapter 9, page 220) along with the context of observations and artifacts. Users are first interviewed to ask them how they accomplish a task and other information surrounding their work. Users are then observed doing the task(s) in question, focusing on processes and tools. Artifacts are collected and discussed. Rather than a general observation guide, investigators use a standard set of questions developed specifically for the questions they are interested in to guide the visits but remain flexible throughout.

This approach is characterized as “top-down”—in contrast to contextual inquiry’s “bottom-up” approach— because the interviews form a general framework from which to interpret specific observations. This technique takes considerably less time than some of the other techniques described above, but it also limits the data you collect because the framework acts as a guideline.

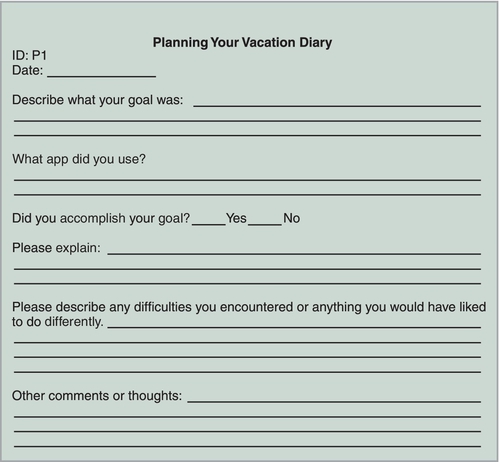

Method Supplements

There are four activities that you can conduct in addition to the above methods or use as stand-alone techniques: artifact walk-throughs, photographs, observing while absent, and dairies. A sample incident diary is presented in Figure 13.4; see Chapter 8 on page 194 for a thorough discussion of diary studies. Each of the other supplements are discussed below.

Artifact Walk-throughs

Artifact walk-throughs are quick and easy but provide indispensable data. Begin by identifying each artifact a participant leverages to do a particular task. Artifacts are objects or items that users use to complete their tasks or that result from their tasks. These can include the following:

■ “Official” documents (e.g., manuals, forms, checklists, standard operating procedures)

■ Handwritten notes

■ Documents that get printed out as needed and then discarded

■ Communications (e.g., interoffice memos, e-mails, letters)

■ Outputs of tasks (e.g., confirmation number from travel booking)

■ Text messages

Next, ask participants to walk you through how the artifacts are used. You want to understand what triggers the use of each artifact: when is it used and for what. Whenever possible, get photos or copies of each artifact. If there are concerns about sensitive or private information (e.g., patient information, credit card numbers), ask for a copy of the original, redact the sensitive data by marking it out with a Sharpie, make a copy, and return the original to the owner or shred it. This takes a little extra time, but most participants are willing to help wherever possible and appreciate your willingness to preserve their privacy. You can also sign a company’s nondisclosure agreement, promising that you will keep all data collected confidential (refer to Chapter 3, page 66). The information obtained during an artifact walk-through will be essential if you want to conduct an artifact analysis (see “Data Analysis and Interpretation” section, page 415).

Photographs

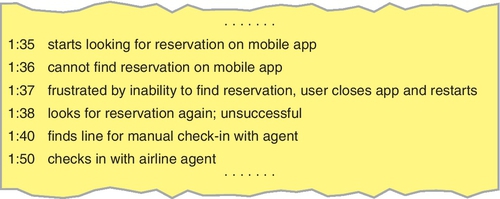

Another supplement that can be useful is to collect photographs of artifacts (e.g., printouts, business cards, notes, day planners) and the environment. This is a method that is commonly used in Discount User Observation (DUO; Laakso, Laakso, & Page, 2001). In this method, two researchers help with data collection. The first is a notetaker and is responsible for taking detailed, time-stamped notes (see Figure 13.5) during the visit and asking clarifying questions. The second researcher acts as a photographer. Since digital cameras typically include automatic time stamps, we find that these make reconciling the time-stamped notes with the time-stamped photos easy and provide a timeline of the user’s work. Following data analysis, a summary of the results is presented to users for verification and correction (see “Data Analysis and Interpretation” section, page 415). The goal is to understand the complex interdependencies of tasks, interruptions, and temporal overlaps (i.e., two actions occurring at the same time) without having to spend significant amounts of time transcribing, watching videos, or confusing raw data with inferences and interpretations.

Observing While You Are Not Present

You can observe users even when you are not present by setting up a video camera and then leaving. This is an excellent way to understand detailed steps a user takes, especially in small environments where observers cannot fit or critical jobs where you do not want to interrupt or distract the user. For example, if you wanted to study how drivers and passengers interact with their dashboard during a road trip but you either did not physically fit in the car or did not want to alter the behavior of the driver and passenger during the drive, you could set up a camera to record their activities and then view the recordings later. Researchers have used this technique to formulate questions and then set up another appointment with the participants a few days later to view the recordings together while the participants provided a running commentary (called “retrospective think aloud” or “stimulated recall;” Ramey, Rowberg, & Robinson, 1996). This technique is referred to as "stream-of-behavior chronicles." In this technique, interviewers insert questions along the way, and to analyze the data, they categorize and index specific behaviors.

Preparing for a Field Study

Now that you are familiar with some of the techniques available to you, it is time to plan and prepare for your field study. Although some of the details may vary slightly depending on the data-collecting technique selected, the preparation, participants, and materials remain constant.

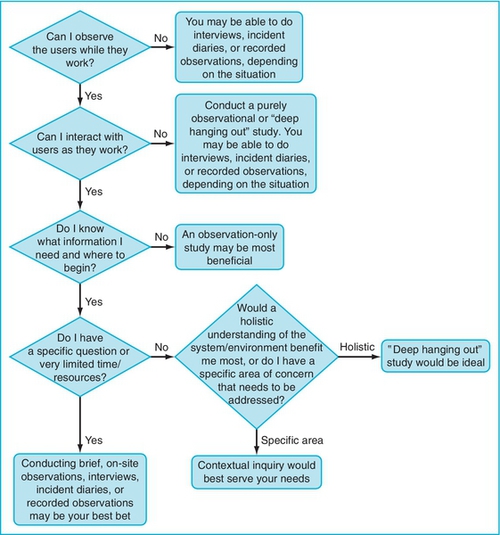

Identify the Type of Study to Conduct

To identify the type of study you would like to conduct, use the decision diagram in Figure 13.6.

Scope your study appropriately. You may not have time to learn everything you would like to or be able to visit all the sites you are interested in. It is critical to the success of your study to plan carefully. Create a realistic timetable for identifying the sites, recruiting the users, collecting the data, and then analyzing the data. You will have questions later on (usually during the analysis stage). If possible, leave enough time to conduct follow-up interviews. There is nothing more frustrating than running out of time and not being able to analyze all the data you have! And remember, it always takes longer than you think—so include enough extra time in case you run into snags along the way.

Write a proposal (see Chapter 6, “Creating a Proposal” section, page 116) that establishes the objectives of the study and identifies the user and site profile, the timeline, the resources needed (e.g., budget, materials, contacts, customers) and from whom, and how the information you collect will benefit the company, the product, and the design.

Players in Your Activity

In addition to participants to observe, there are a few other roles you may need to fill for your study. Each one is described below.

The Participants

Once you know the type of study you would like to conduct, you need to identify the user type to investigate (see Chapter 2, “Learn About Your Users” section, page 35). As with any of the techniques described in this book, the data you collect are only as good as the participants you recruit.

Create a screener to guide your recruitment (see Chapter 6, “Recruitment Methods” section, page 139), and make sure everyone is in agreement before you start recruiting participants.

How Many Participants?

There is no set number of users or sites to observe. You simply continue to observe until you feel you understand the users, tasks, or environment and you are no longer gaining new insights with each new user or site. Some researchers recommend 15-20 users (e.g., in contextual inquiry), but time and cost restraints mean that four to six (per user type) is more common in industry practice. In academic settings, the number of participants depends on whether or not you are planning to conduct statistical tests (see Chapter 5, “Number of Users” section, page 104). Other factors to keep in mind are getting a diverse range of users and sites.

Diverse Range of Users and Sites

Get a broad representation of users and sites. This includes industry, company size, new adopters, and long-time customers, as well as geographic location, age, ethnicity, and gender diversity. Try to get access to multiple users at each site. They may be doing the same task, but each person may do it differently and have different ideas, challenges, work-arounds, etc. You also want a mix of experts and novices. Contacts at a given company will likely introduce you to their “best” employees. Explain to the contacts the value in observing both expert and novice users. In the end, though, politics and people’s availability may determine your choice of sites and users to observe. Do everything you can to ensure that participants and sites meet the profile you are interested in. Stakeholders often have the contacts to help you identify sites and users, so get them involved in this step. It will help you and also help stakeholders buy in to the process.

When you begin recruiting, start small; do not recruit more users or sites than your schedule will permit. If your first set of visits is successful, you can leverage that success to increase the scope of your study. In addition, you may need to start with local sites for budgeting reasons, but if your study is successful, you could be given the opportunity to expand later.

The Investigators

Begin by identifying who wants to take part as genuine data collectors, not just as curious onlookers. You may be surprised to discover how many people want to be present during your field visits. In purely observational or deep hanging out studies, this is not a big issue. You should welcome some additional help in collecting data. It will speed the process, and an additional set of eyes can bring a fresh perspective to the data analysis. Expect and encourage people to get involved, but be aware of some of the issues surrounding inexperienced investigators.

You may want to establish a rule that anyone present at the site must participate in the data collection and follow a set of ground rules (see “Train the Players” section, page 404). This is where you must establish yourself as the expert and insist that everyone respect your expertise. Sometimes, you need to be diplomatic and tell a stakeholder that he or she cannot attend a particular visit, without ruining your relationship with that stakeholder.

Once you have a list of people who want to take part in the study, look for those who are detail-oriented and good listeners. For studies that involve some level of interaction, we recommend working in teams of just two, because that is less overwhelming for the participant being observed. Each team should consist of an investigator and a notetaker and a videographer/photographer (page 403). Since the video camera can usually be set up in the beginning and left alone, either the investigator or notetaker can do this. Either the notetaker or investigator can double up as photographer. Mixed-gender teams can help in cases where a participant feels more comfortable relating to one gender or another. For safety reasons, we recommend never conducting field studies in people’s home or other private spaces alone.

The job of the investigator is to develop rapport with the participant, and if applicable, conduct the interview and apprentice with him or her. The investigator is the “leader” in the two-person team. In cases where you lack a great deal of domain knowledge, you may not know enough about what you are observing to ask the user follow-up questions. You may wish to create more of a partnership with a developer or product manager. You can begin by asking participants each question, but the domain expert would then follow up with more detailed questions. Just be sure that one of you is capturing the data! Alternatively, you can bring a “translator” along with you. This may be a user from the site or an expert from your company who will provide a running commentary while the participant is working. This is ideal in situations where the participant cannot provide think-aloud data and cannot be interrupted with your questions. In a healthcare field study we conducted, we asked a member of the product team who was a former registered nurse to act as a translator for us. She pointed out observations that were interesting to her and that we would not have noticed. She also explained the purpose of different artifacts when users were not available to discuss them. Her help was priceless!

If you have more potential investigators than you have roles, you may choose different investigators for each site. This can lower interrater reliability (i.e., the degree to which two or more observers assign the same rating or label to a behavior; see page 254), but it may also be necessary if individual investigators do not have the time to commit to a series of visits. Having a single person who attends all visits (i.e., yourself) can ensure continuity and an ability to see patterns or trends. Having a new investigator every few visits provides a fresh set of eyes and a different perspective. It also breaks up the workload and allows more people to take part in the study. You are sharing the knowledge, and important stakeholders do not feel excluded.

If time is a serious issue for you, it may be wise to have more than one collection team. This will allow you to collect data from multiple sites at once, but you will need to train several people and develop an explicit protocol for investigators to follow (see “Develop Your Protocol” section, page 405). If there is more than one experienced user experience professional available, pair each one up with a novice investigator. Having more than one collection team will mean that you will lose that consistent pair of eyes, but it may be worthwhile if you are pressed on time but have several sites available to you.

The Notetaker

In addition to an investigator, a notetaker is required. The investigator should be focused on asking questions and apprenticing with the user (if applicable), not taking detailed notes. You will find a detailed discussion of notetaking tips and strategies in Recording and Notetaking on page 171. The notetaker can also serve as a timekeeper, if that is the information you wish to collect. You may also wish to have the notetaker serve as the videographer/photographer (page 404). Lastly, it is also important to have an additional pair of hands on-site to set up equipment, and the notetaker can serve this purpose. If it is not possible to have a notetaker, one alternative is to record the session, and then, the investigator can take notes after the session is over. We do not recommend this, however.

The Videographer/Photographer

Whenever possible, you will want to video record your field study. You will find a detailed discussion of tips for recording video and the benefits of video recordings in Recording and Notetaking (page 171). In most cases, this person simply needs to start and stop the recording, insert new media (e.g., SD card) as needed, and keep an eye out for any technical issues that arise.

You may also want someone to take photographs. (Again, the notetaker can often take on the roles of videographer and photographer.) Capturing visual images of the user’s environment, artifacts, and tasks is extremely valuable. It helps you remember what you observed, and it helps stakeholders who were not present to internalize the data. Even if you do not plan to include pictures of participants in your reports or presentations, they can help you remember one participant from another. A digital camera with a screen is advantageous, because if the user is nervous about what you are capturing, you can show him or her every image and get permission to keep it. If the user is not happy with the image, you can demonstrate that you deleted it.

Account Managers

The account manager or sales representative is one person who may insist on following you around until he or she feels secure in what you are doing. Since this is the person who often owns the sales relationship with the customer and must continue to support the customer after you are long gone, you need to respect his or her need for control. Just make sure the account manager understands that this is not a sales demo and that you will be collecting the data. We have found that account managers are so busy that they will often leave you after an hour or less.

Train the Players

You are entering someone’s personal space; for some users, this can be more stressful for the user than going to a lab. You will also likely need to leverage multiple skill sets such as interviewing, conducting surveys, observing, and managing groups of people. If you or a colleague has not conducted a field study before, we recommend reviewing “Moderating Your Activity” section on page 165 in Chapter 7 for a foundation in moderating. You may also want to sign up for a tutorial at a conference hosted by a professional organization to get hands-on training for one of the particular techniques. (EPIC, UPA, ACM SIGCHI, and HFI often offer workshops on field studies led by experts in the field, such as Susan Dray, David Siegel, and Kate Gomoll.) Shadowing an experienced user research professional is another option, but it is more difficult to do, since the primary investigator will want to reduce the number of observers to an absolute minimum.

Even if the people available to collect data are all trained user research professionals, you want to ensure that everyone is on the same page—so a planning and/or training session is essential. Begin by identifying roles and setting expectations. If you need the other investigator to help you prep (e.g., copy consent forms, QA equipment), make sure he or she understands the importance of that task. You do not want to get on-site only to find that you do not have the consent forms because of miscommunication or because the other investigator was annoyed at being your “assistant.” Also, make sure that everyone is familiar with the protocol that you will be using (see Chapter 6, “Creating a Protocol” section, page 153).

If you will be observing participants use your products in the field, make it clear to all investigators that they are not there to “help” the participant. It is human nature to want to help someone who is having difficulty, but all the investigators need to remember that they will not be there to help the user later on. One humorous user experience professional we know keeps a roll of duct tape with him and shows it to his coinvestigators prior to the visit. He informs them that he will not hesitate to use it should they offer inappropriate help or comments during the visit. It gets a laugh and helps colleagues remember the point.

If this will be an ongoing field study (rather than a one-time visit), you may want inexperienced investigators to read this chapter, attend workshops, practice during mock sessions, or watch videos of previously conducted field studies. Develop standardized materials (see “Activity Materials” section, page 407) and review them with all investigators. Additionally, everyone should know how to use each piece of equipment and how to troubleshoot problems with the equipment. Practice setting up and packing up equipment quickly. Labeling cords for easy identification will make setting up much faster. Finally, identify a standard notetaking method and shorthand for easy decoding.

Develop Your Protocol

By now, you have selected the type of field study you will conduct. Now, you need to identify your plan of attack or protocol. This is different from your observation guide (a list of concerns or general areas to observe). A protocol can include how you will interact with users (the observation guide is part of that), how much time you plan to spend observing each user/area, and what instructions you will give users (e.g., think-aloud protocol) if you are interacting with them. You should also identify any activities that you want other investigators to participate in. The answers to these and many other questions need to be spelled out in a protocol (see Chapter 6, “Creating a Protocol” section, page 153). Without a protocol, you do not have a script for everyone to follow, and each investigator will do his or her own thing. Even if you are doing the study alone, you risk standardization in your data collection because you may end up conducting each visit differently, forgetting some questions, haphazardly adding in others. A protocol allows you to collect the data in the most efficient and reliable manner possible. It also allows you to concentrate on the data collection, not trying to remember what you forgot this time.

Schedule the Visits

After you have selected your investigators, get commitment from each one and include them in scheduling discussions. They must agree to be present at the visits they are scheduled for, and they must be willing to receive training. If they do not have time for either of these, it is best to find someone else.

Below are some things to consider when scheduling your visits. The questions below may seem obvious, but when you are in the middle of creating the schedule, many obvious details are forgotten.

■ Where is the site? How long will it take to get there? If there will be a significant drive and traffic will likely be a problem, you do not want to schedule early morning appointments.

■ Have you checked to see if your contact or the user’s manager should be called or scheduled as part of the visit?

■ Do you plan to visit more than one site per day? How far apart are they? Will there be traffic? What if you are running behind schedule at the other site? If you must visit more than one location per day, put in plenty of pad time between sites.

■ Include breaks between users or sites in your schedule. This will allow you to review your notes, rest, eat a snack, check your messages, etc. You do not want a growling stomach to interrupt your quiet observations.

■ Make sure you are refreshed for each visit. If you are not a morning person, do not schedule early morning appointments. Or if your energy tends to run out at the end of the day, schedule interviews early in the day and catch up on e-mail in the afternoon. You do not want the user to see you yawning during the interview.

■ Consider the user’s schedule:

![]() Lunchtime may either be good or bad for users. Find out what they prefer and what their workload might be during that time (see next point).

Lunchtime may either be good or bad for users. Find out what they prefer and what their workload might be during that time (see next point).

![]() Some users want you there when work is slow so you will not disturb them. You want to be there when things are busy! Make sure that the time the user suggests for your visit will allow you to observe what you are interested in.

Some users want you there when work is slow so you will not disturb them. You want to be there when things are busy! Make sure that the time the user suggests for your visit will allow you to observe what you are interested in.

![]() Consider the cyclical nature of work. Some tasks are done only during certain times of the year. If you are interested in observing the harvest, for example, there is a limited window in which you can observe.

Consider the cyclical nature of work. Some tasks are done only during certain times of the year. If you are interested in observing the harvest, for example, there is a limited window in which you can observe.

![]() Some days of the week are worse than others (e.g., Monday and Friday). As a general rule, avoid Monday mornings and Friday afternoons. Also, find out if there are standard “telecommuting” days at your user’s site.

Some days of the week are worse than others (e.g., Monday and Friday). As a general rule, avoid Monday mornings and Friday afternoons. Also, find out if there are standard “telecommuting” days at your user’s site.

![]() Be prepared to compromise. Your users have lives to live and your study is likely low on their priority list. You may have to change your original plan or schedule, but stay open-minded and thankful that some data are better than none.

Be prepared to compromise. Your users have lives to live and your study is likely low on their priority list. You may have to change your original plan or schedule, but stay open-minded and thankful that some data are better than none.

■ Do not forget the other investigators. Ask them for their availability. Find out whether they are morning or evening people. It is not any less offensive for the notetaker to be yawning during an interview.

■ Find out how to make copies or print files if you do not want to ship paperwork. Can you use the user’s facilities, or will you have to find a local copy shop?

■ Finally, consider the haphazard schedule of some occupations (e.g., surgeons, flight crew). They may agree to participate but be pulled away to activities you cannot observe. Be prepared to wait long periods of time. Bring other work with you to do and/or have a list of things to observe that do not require interacting with participants. Also, be prepared to take advantage of sudden opportunities.

The final thing to keep in mind when scheduling is burnout. Burnout is a risk for extended studies. Field studies are intense activities where you must be “on” at all times. It is time- and energy-consuming to conduct each visit and analyze the data. You can also suffer from information overload. All of the sites or users tend to blur together after a while. And travel can be stressful. Take the “fatigue factor” into consideration when scheduling the visits and determining the timeline for analyzing data. Unfortunately, you may be placed in the situation where you must visit six sites in three days and there is no way around it. Alternating the roles of notetaker and interviewer between yourself and your colleague can give you a break and help build more novice team member’s skills. At least, you will not have to be “on” for every participant (e.g., encouraging participants to think aloud, following up on questions, and apprenticing). You will still be exhausted, but you will get a small “break” every other participant.

Activity Materials

You may have many materials to take to each site; it depends on the type of study you are conducting and what is permitted on-site. Below is a list of suggested materials for most types of studies, but you should tailor this for your own study and include more detail in your own checklist. This is the best way to stay organized and keep your study running smoothly from one site to the next. Without your checklist, you will likely forget at least one thing each time.

Checklist of All Materials and Equipment Needed

■ Contact information for each participant

■ Directions and map to site

■ Consent forms and confidentiality agreements

■ Protocol

■ Observation guide

■ Visit summary template

■ Schedule

■ Method of notetaking (audio recorder and/or paper and pencil)

■ Peripherals (e.g., batteries, SD cards, extension cords, power strip)

■ Method for collecting artifacts (e.g., accordion folder, notebook, hole puncher)

■ Method for carrying all the equipment (e.g., small suitcase, luggage cart)

■ Thank-you gift for participant(s)

■ Business cards for participants to contact you later with questions or additional information

■ Video recorder or camera and audio recorder (if permission has been obtained to record)

We recommend providing an incentive for participants (see Chapter 6, “Determining Participant Incentives” section, page 127). We also recommend getting a small token gift for anyone who helped arrange your access to the site or users (e.g., account/product manager). This individual may have spent significant time finding people in the company to match your user profile or helping you to arrange your visit. It never hurts to show your appreciation, and it can also help if you ever need to access that site again. When selecting the gift, keep in mind that you must carry it along with the rest of your equipment. You do not want to carry around several shirts in each size or heavy, breakable coffee mugs. Instead, opt for a light, small, one-size-fits-all gift such as a USB drive with your company logo.

As we mentioned earlier, it is important to develop an observation guide (see Figure 13.2). This will help ensure you address each of the goals of your study. Next, use your observation guide to develop a visit summary template (see Figure 13.7). This is a standardized survey or worksheet given to each investigator to complete at the end of each visit. This helps everyone get his or her thoughts on paper while they are fresh. It also speeds data analysis and avoids reporting only odd or funny anecdotal data. Stakeholders who are eager for immediate results can read the summary worksheets and know what the key points are from each visit. They will appreciate being kept in the loop and will be less likely to insist on being present at each site if they feel you are promptly providing the information.

Although this can be the most thought-provoking information and can bring your users to life for stakeholders, it should not be the only data you report. The template should be flexible enough so that you can record data that you had not anticipated and avoid losing important insights. You may also further develop the template as you conduct more visits. Just make sure that everyone who views the summaries understands that he or she is viewing summary data from one data point. He or she should not begin building the product or making changes to his or her existing product based on his or her interpretations of that data.

Create any incident diaries, surveys, prototypes, or interview worksheets you may need during your study. You can also send any previsit activity materials before your visit to help you develop your observation guide (e.g., mailing out a survey in advance). Incident diaries are another valuable tool to send out prior to your visit. The surveys and diaries will be extremely useful if you know you will have limited time with each participant.

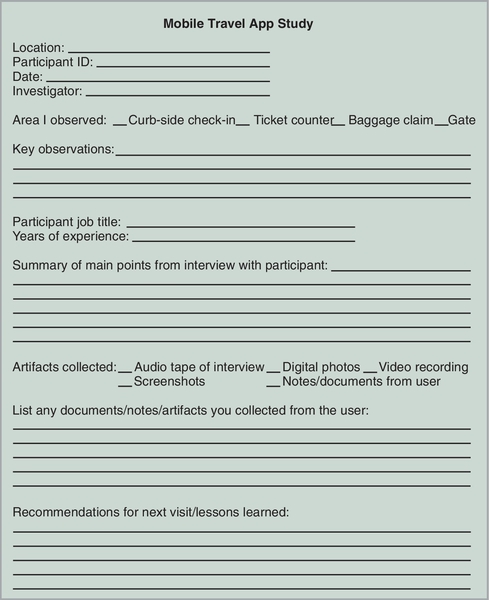

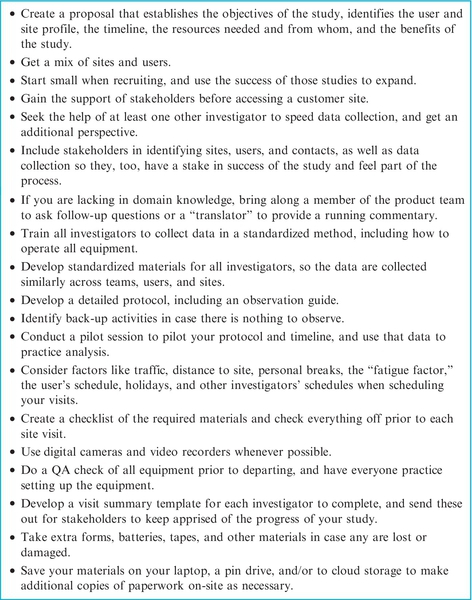

Summary

We have provided a lot of information to help you prepare for your field study. Figure 13.8 summarizes the main points. Use this checklist when preparing for your study.

Conducting a Field Study

The specific procedure for your field study will vary depending on the type of study you conduct. We can offer some high-level tasks to conduct, regardless of the type of study. Just remember to remain flexible.

Get Organized

If the visit has been arranged (i.e., this is not a public location where you can observe users unnoticed), upon arrival, meet with your site contact. Familiarize yourself with the environment. Where is the bathroom, kitchen, copier, etc.? Where can you get food (if that has not been planned for you already)? If your site contact will not be with you throughout the visit, how will you get to your next appointment, and so forth? If there are multiple investigation teams, decide where and when you will meet up again. Arrive at least 15 minutes before your first scheduled appointment to take care of these details. Be prepared for some extra handshaking and time at this point. You may need to say “hello” to the contact’s or user’s boss. This is another good reason for being early.

Meet the Participant

Again, if your visit is arranged, go to your first scheduled appointment on time. Introduce yourself and any other investigators or observers with you. All participants should be aware of their rights, so ask them to sign a consent form at the beginning. Do not forget to make copies of those forms for the user, if he or she wants them (refer to Consent Forms, page 66, for more information).

Explain what you will be doing and your time frame. Also, state clearly that the participant is the expert, not you. Remind the participant that he or she is not being evaluated in any way. While you are going over the forms and explaining these points, the other investigator should be setting up the equipment. If you must invade a colleague’s space, ask for permission and treat that person with the same respect you are showing your participant. This may sound obvious, but it is easy to overlook common courtesies when you are wrestling with equipment and trying to remember a million different things. This is when your protocol will come in handy.

Next, get a feel for the user’s environment (e.g., take pictures, draw maps, record sticky notes, note lighting, equipment, background sounds, layout, software used). While the notetaker is doing this, the interviewer should begin developing a rapport with the user. Give the participant time to vent any frustrations about your product or his or her job in general. If the user has product-specific questions or enhancement requests, state that you can record these questions and take them back to the product team, but do not attempt to answer them yourself. Participants will be curious about you and the purpose of the study. They may also ask for help. State that you cannot give advice or recommendations and that you are there simply to observe. At the end of the session, you may choose to provide the user with help, both to repay the user and to learn more about why the user needed help in the first place. Throughout, be polite and show enthusiasm. Your enthusiasm will rub off on others and make the participant feel more comfortable.

If you plan to set up recording equipment and leave for a few hours, you should still review the consent form with the participant and have a discussion to make sure the participant is comfortable with being recorded. You may think that it is not necessary to establish rapport with the user; but if you want the participant to behave naturally, he or she needs to understand the purpose of your study and have the opportunity to ask questions. Enthusiasm is important, even if you will only be there for 10 minutes.

Begin Data Collection

Now, it is time to begin your selected data collection technique. Use an appropriate notetaking method. If you do not want people to notice you, select an inconspicuous method (e.g., a small notepad). If it is not necessary to de-emphasize your actions, a laptop and digital voice recorder may be better.

Know the Difference Between Observations and Inferences

It is very important to know the difference between capturing observations and making inferences. Observations are objective recordings based on what you have seen or heard, whereas inferences are conclusions based upon reasoning. For example, an observation may be that a flight attendant interacting with clients is always smiling and is very cheery and pleasant. This is good information to record, but do not infer from that observation that the flight attendant loves his job—he may feel extremely overworked but has learned to hide it with a smile. Unless you verify your interpretations with the participant, do not record your assumptions as facts.

Wrap-Up

Once you have completed your selected data collection technique or when your time with the participant is up, wrap up the session. Make sure you leave time at the end to provide any help that you promised earlier and to answer additional questions the participant may have. While the interviewer thanks the participant and answers questions, the notetaker should be packing up all materials and equipment. You may wish to leave behind follow-up surveys or incident diaries. This is also a good time to schedule follow-up visits. You will often find during data analysis that you have unanswered questions that require a second visit.

Organize Your Data

After the session, you will find it useful to compare notes, thoughts, and insights with your fellow investigators. Now is the time to get everything on paper or record the discussion on a digital voice recorder. You can complete the visit summary template individually or together. You may be tired after the session and just want to move on to the next appointment or wrap up for the day, but be sure to leave time to debrief with your team and document your observations right now. Doing this now will allow you to provide quick interim reports, and it will make data analysis much easier.

Now is also the time to label all data (e.g., digital recordings, surveys, artifacts) with a participant ID (but not his or her name, for confidentiality reasons), date, time, and investigation team. If you are keeping paper copies, you may want to have a large manila envelope to keep each participant’s materials separate. It is a terrible feeling to get back to the office and not know which user provided a set of artifacts or who completed a certain survey.

When you return to the office, scan in artifacts, notes, and photos. In addition to sending out the visit summary report, you can include electronic files or physical copies of the artifacts to stakeholders without worrying about losing the originals. However, this is time-consuming if you have lots of artifacts. (We collected nearly 200 documents from one hospital during our healthcare field study!)

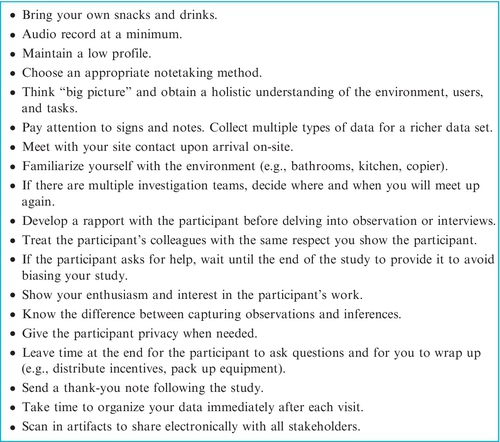

Summary

We have given a lot of recommendations about how to conduct a successful field study. For easy referral, they are summarized in Figure 13.9.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

At this point, you have a stack of visit summary worksheets and other notes and artifacts from your visits to wade through. The task of making sense out of all the data can seem daunting. Below, we present several different ways of analyzing the data. There is no one right way—you have to select the method that best supports your data and the goals of your study. The goal of any of these data analysis techniques is to compile your data and extract key findings. You do this by organizing and categorizing your data across participants. Before you begin your analysis, there are few key points to keep in mind:

■ It is all good data. Some points may not seem to make sense or it may be difficult to bring it all together, but the more time you spend with the data, the more insight you will gain from it. In other words, your first impression will not be your last.

■ Be flexible. If you planned to analyze your data with a qualitative data analysis tool but it is not working for you, consider an affinity diagram or a quantitative summary.

■ Do not present raw data. It can be quite challenging to take the detailed data from each visit and turn them into actionable recommendations for the product team. However, neither designers nor product developers want the plethora of raw data you collected. You need to compile the information, determine what is really important, and highlight it for your audience.

■ Prioritize. You will likely end up with a lot of data and may not have the time or resources to analyze them all at first. Analyze the data, first based on the goals of your study, and then, you can go back and search for other insights and ideas.

■ Frequency does not necessarily mean importance. Just because a user does a task frequently, that does not necessarily mean it is critical to the user. Keep the context and goals of the user’s actions in mind during analysis.

Select Your Analysis Method

The method you select to structure or organize data should depend on the goals of your study and how you collected the data. Regardless of the data collection technique used (e.g., contextual inquiry), the data you collect in a field study are similar to the data you collect using other user research methods. Therefore, you can use many of the analysis techniques presented in other chapters (e.g., affinity diagram, coding qualitative data). Pick the analysis method that best fits your data or the goals of your study. We provide a brief overview of some of the most common analysis methods here.

Affinity Diagram

An affinity diagram is one of the most frequently-used methods for analyzing qualitative data. Similar findings or concepts are grouped together to identify themes or trends in the data and let you see relationships. A full discussion of affinity diagrams is presented on page 363 in Chapter 12.

Analyzing Deep Hanging Out Data

It is best to begin by going around the room and asking each person to provide a one-sentence summary for each focus area (refer back to Table 13.2 on page 390). Ask the following questions when analyzing the data:

■ What were the biggest/most important findings?

■ What were the immediate impressions?

■ What sticks out or really grabs you?

■ Are there themes/patterns/coherence?

■ What’s the story? What is the key takeaway?

■ What surprised you and what didn’t?

■ What is the disruptive or challenging information?

■ If you could go back again, what else would you do or what would you do differently?

■ What do you wish you paid more attention to?

■ If more than one person studied a focus area or observed a single user, what are the similarities and differences found?

■ What’s considered normal in this context? (And therefore, what kinds of patterns or behaviors would be considered aberrations?)

Upon answering these questions, you can begin organizing the data.

Analyzing Contextual Inquiry/Design Data

If you have conducted a contextual inquiry to prepare for another user research activity (e.g., identify questions for a survey) to better understand the domain or as an innovation exercise, you can choose the most appropriate data analysis technique for the type of data you have. If, however, you conducted a contextual inquiry to inform your design decisions, you are ready to move into contextual design. Contextual design is complex and beyond the scope of this book. We recommend referring to Beyer and Holtzblatt (1998) for information on contextual design.

Grounded Theory

Grounded theory is not only a form of analysis, but an approach to inquiry. The goal is to derive an abstract theory about an interaction that is grounded in the views of users (participants). In this method, researchers engage in constant comparison including coding, memoing and theorizing as data are collected, rather than waiting to examine data once it is all collected. The emphasis is on the emergence of categories and theories based in the data, rather than using a theory to derive a hypothesis which is then tested as in positivist inquiry. A complete discussion of grounded theory is outside of the scope of this book. We recommend referring to Creswell (2003) and Strauss and Corbin (1990) for more information.

Qualitative Analysis Tools

There are times when you need an analysis method that is more systematic and reproducible than an affinity diagram, the results of which may differ depending on who participates, instructions given, etc. In cases where you need this kind of rigor, we recommend employing qualitative analysis tools and checking the reliability of your coding using a measure of interrater reliability such as Cohen’s kappa (see Chapter 9 “How to Calculate Interrater Reliability,” page 254). There are a variety of tools available such as nVivo and maxQDA that you can use to code qualitative data. Refer to Chapter 8 on page 194 for a description of each tool and the pros and cons of using such tools.

Communicating the Findings

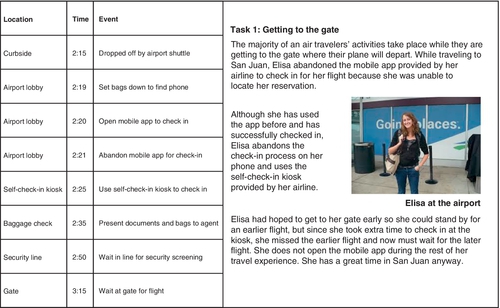

Because the data collected during field studies are so rich, there is a wide variety of ways to present the data. For example, data may be used immediately for persona development, to develop an information architecture, or to develop requirements for the project. Leveraging several of these techniques below will help bring stakeholders closer to the data and get them excited about your study. There is no right or wrong answer; it all depends on the goals of your study and the method you feel best represents your data. In the end, a good report illuminates all the relevant data, provides a coherent story, and tells the stakeholders what to do next. One way to present data is in a timeline (see Figure 13.10). Below, we offer some additional presentation techniques that work especially well for field study data. For a discussion of standard presentation techniques for any requirements method, refer to Chapter 15 on page 450.

Two frequently-used methods for presenting or organizing your data are the artifact notebook and storyboards.

■ Artifact notebook. Rather than storing away the artifacts you collected in some file cabinet where people will not see them, create an artifact notebook. Insert each artifact collected, along with the information about how the artifact is used, the purpose, and the implications for design. Keep this notebook in an easily accessible location. You can create several of these and include them as educational material for the product development team.