CHAPTER NINE

UNDERSTANDING PEOPLE IN PUBLIC ORGANIZATIONS

Motivation and Motivation Theory

Obviously the people in an organization are crucial to its performance and to the quality of work life within it. This chapter and the next one are concerned with the people in public organizations. They emphasize public employees’ motivation and work-related values and attitudes. This chapter defines motivation and discusses it in the context of public organizations. It then describes the most important theories of work motivation. Chapter Ten describes concepts important to the analysis of motivation and work attitudes, including concepts about people’s values, motives, and specific work attitudes such as work satisfaction. It covers the values and motives that are particularly important in public organizations, such as the desire to perform a public service, and values and attitudes about pay, security, work, and other matters that often distinguish public sector managers and employees from those in other settings.

These topics receive attention in every textbook on organizational behavior because of their fundamental importance in all types of organizations. In public organizations and public management they have been receiving even greater attention in recent years than in the past. The U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM) (2013) surveys federal employees and managers (687,000 in 2012) about their perceptions and attitudes about leadership in their agencies, their work satisfaction. The OPM Web site for the surveys encourages agency representatives to compare their agency’s results with the government-wide results and with those of other agencies. Obviously, OPM representatives and OPM stakeholders regard employee attitudes and perceptions as very important, and regard the surveys as a valuable diagnostic resource. One such stakeholder is the Partnership for Public Service, a nonprofit organization that seeks to promote and support public service. The Partnership uses the results of surveys of large samples of federal employees to develop rankings of the “best places to work” in the federal government (Partnership for Public Service, 2013a). Federal agency administrators take these rankings very seriously. Agencies that do well in the rankings post this information on their Web sites (see http://www.gao.gov, and http://www.ssa.gov). Other agencies acknowledge the importance of the topic by setting objectives of becoming “a best place to work.” The U.S. Internal Revenue Service (2013, p. 24) strategic plan includes the strategic objective of making the IRS the best place to work in government. The U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board also conducts periodic federal employee surveys, and uses the results to produce reports on such topics as “employee engagement” in their work and their agencies (U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, 2012). Some of these surveys have used ideas and questions based on motivation theories that we will cover in this chapter. State and local governments conduct employee surveys as well (for example, State of Washington, 2012). These developments make it important for persons preparing for roles in government service, or serving in such roles, to gain a firm grounding in the theories, concepts, and methods for analyzing the attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors of human beings in their organizations and workplaces. This and the next chapter aim to support such efforts.

Motivation and Public Management

Human motivation is a fundamental topic in the social sciences, and motivation to work is similarly a basic topic in the field of organizational behavior (OB). The framework presented in Figures 1.1 and 1.2 in Chapter One indicates that the people in an organization, and their behaviors and attitudes, are interrelated with such factors as organizational tasks, organizational structures and processes, leadership processes, and organizational culture. With all of these factors impinging on people, motivating employees and stimulating effective attitudes in them become crucial and sensitive challenges for leaders. This and the next chapter show that, as with many topics in management and OB, the basic research and theory provide no conclusive science of motivation. Leaders have to draw on the ideas and apply the available techniques pragmatically, blending their experience and judgment with the insights the literature provides.

These two chapters show that OB researchers and management consultants often treat motivation and work attitudes as internal organizational matters influenced by such factors as supervisory practices, pay, and the nature of the work. Such factors figure importantly in public organizations; however, motivation in public organizations, like the other organizational attributes discussed in this book, is also greatly affected by the public sector environment. The effects of this environment require public managers to possess a distinctive knowledge of motivation that links OB with political science, public administration, and public policy processes.

The effects of the political and institutional environment of public organizations on the people in those organizations show up in numerous ways. In recent decades, governments at all levels in the United States and in other nations have mounted efforts to reform governmental administrative systems to improve the management and performance of those systems (Gore, 1993; Peters and Savoie, 1994; Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2011; Thompson, 2000). Often, the reformers have sought to correct allegedly weak links between performance and pay, promotion, and discipline, claiming that these weak links undermine motivation and hence performance and efficiency. These reforms have not been attempted just because of public and officials’ concerns about government performance. Government managers have for decades complained about having insufficient authority over pay and discipline, and other managerial responsibilities that they have (Macy, 1971; National Academy of Public Administration, 1986). The reforms also reflect, then, the context in which public managers and organizations operate, that earlier chapters have described. That such reforms have often foundered (Ingraham, 1993; Kellough and Lu, 1993; Perry, Petrakis, and Miller, 1989) raises the possibility that these constraints are inevitable in the public sector (Feeney and Rainey, 2010). Many analysts and experienced practitioners regard the constraining character of government personnel systems as the critical difference between managing in the public sector and managing in a private organization (Thompson, 1989; Truss, 2013), and for decades government officials have sought to decentralize government personnel systems to provide them with more flexibility in human resource management (for example, Gore, 1993).

If anything, the focus on the management and motivation of public employees intensified as the new century began. A human capital movement got under way in the federal government, with implications for the other levels of government. This emphasis on human capital reflects the assumption that the human beings in an organization and their skills and knowledge are the organization’s most important assets, more important than other forms of capital such as plants, machinery, and financial assets. Accordingly, organizations must invest in the development of their human capital. The U.S. General Accounting Office, the U.S. Office of Personnel Management, and the U.S. Office of Management and Budget joined in trying to develop human capital policies and models and to get federal agencies to adopt them (see, for example, U.S. General Accounting Office, 2002a, 2002b). The legislation authorizing the creation of the new Department of Homeland Security in 2002 contained a provision requiring each federal agency to appoint a chief human capital officer, to engage in strategic planning for human capital, and to engage in other steps to maintain and develop human capital.

In 2013, public controversies and political conflicts erupted over the compensation of state government employees and over the allegedly expensive retirement benefits they receive. “Sequestration,” or withholding of federal funding for agencies and programs, raised the possibility of furloughs for federal employees, who had been subject to pay freezes for several years. The sequestration of funds caused cutbacks in federal programs that affected state and local governments involved in the delivery of those programs. Cutbacks and pay freezes obviously can hurt the morale of federal employees, and represent an example of how developments in the political process can affect the working lives of government employees.

These developments all suggest that motivating people in government, and encouraging their positive work attitudes, raises challenges that can be distinct from those faced by business and nonprofit organizations. They indicate that the political and institutional context of government can influence motivation and work attitudes in government in distinctive ways. As with other topics in this book, however, another side argues that government differs little from business in matters of motivation. Businesses also have problems motivating managers and employees, because of union pressures, selfish and unethical behaviors, ineffective bonus and merit-pay systems, and other problems. In addition, according to Nobel Laureate Herbert Simon (1995), one of the most influential contributors to public administration theory and arguably the world’s preeminent behavioral scientist, reward practices in public, private, and nonprofit firms do not differ: “Everything said here about economic rewards applies equally to privately owned, nonprofit, and government-owned organizations. The opportunity for, and limits on, the use of rewards to motivate activities towards organizational goals are precisely the same in all three kinds of organizations” (p. 283, n. 3). For this reason, the discussion to follow in the next two chapters will pay attention to evidence about whether public organizations and management are distinctive with regard to motivation and work values and attitudes.

This dispute over whether government is different makes it important to look at evidence about it, because the evidence often undercuts negative popular stereotypes and academic assertions. Observations about the distinctive character of government often suggest problems with the motivation and performance of people in government. As we will see, however, evidence often indicates high levels of motivation and positive work attitudes in many government organizations. Executives coming to government from business typically mention how impressed they are with how hard government employees work and how capable they are (Hunt, 1999; IBM Endowment for the Business of Government, 2002; Volcker Commission, 1989). In surveys, government managers have mentioned frustrations of the sort discussed earlier, but have also reported high levels of work effort and satisfaction (see, for example, Light, 2002a; U.S. Office of Personnel Management, 2013).

In this debate over whether there are similarities or differences in managing people in the public and private sectors, in a sense both sides are right. Public managers often do face unique challenges in motivating employees, but they can also apply a great deal from the general motivation literature. The challenge is to draw from the ideas and insights in the literature while taking into consideration the public sector context discussed in other chapters, while basing one’s conclusions on as much actual evidence as possible. The next section reviews the assertions about the public sector context discussed in earlier chapters before the discussion turns to the concept of motivation itself.

The Context of Motivation in Public Organizations

Previous chapters have presented observations and research findings that suggest a unique context for motivation in public organizations (Perry and Porter, 1982):

- The absence of economic markets for the outputs of public organizations and the consequent diffuseness of incentives and performance indicators in the public sector

- The multiple, conflicting, and often abstract values that public organizations must pursue

- The complex, dynamic political and public policy processes by which public organizations operate, which involve many actors, interests, and shifting agendas

- The external oversight bodies and processes that impose structures, rules, and procedures on public organizations, including civil service rules governing pay, promotion, and discipline, and rules that affect training and personnel development

- The external political climate, including public attitudes toward taxes, government, and government employees, which turned negative during the 1970s and 1980s

Earlier chapters have also related these conditions to various characteristics of public organizations that in turn influence motivation:

- There are sharp constraints on some public leaders and managers that limit their motivation and ability to develop their organization. Politically elected and appointed top executives and their appointees turn over rapidly. Institutional oversight and rules limit their authority.

- The turbulent, sporadic decision-making processes in public organizations can influence managers’ and employees’ sense of purpose and their perception of their impact (Hickson and others, 1986; Light, 2002a).

- There are relatively complex and constraining structures in many public organizations, including constraints on the administration of incentives (Feeney and Rainey, 2010).

- Vague goals in public organizations, both for individual jobs and for the organization, can hinder performance goals and evaluation, and can weaken a sense of personal significance within the organization (Buchanan, 1974, 1975; Perry and Porter, 1982).

- Scholars have claimed that people at the lower and middle levels of public organizations often become lost in elaborate bureaucratic and public policy systems. They work under elaborate rules and constraints that, paradoxically, fail to hold them highly accountable (Barton, 1980; Lipsky, 1980; Lynn, 1981; Michelson, 1980; Warwick, 1975).

- On a more positive note, the people who choose to work in government often express high levels of motivation to engage in valuable public service that helps other people or benefits the community or society; they are often motivated by the sense of pursuing a valuable mission (for example, Goodsell, 2011). Government work is often interesting and very important.

Some of these observations are difficult to prove or disprove. For others we have increased evidence, which later sections and the next chapter present. As we examine this evidence, it is important to look at how organizational researchers have treated the concept of motivation and its measurement.

The Concept of Work Motivation

A substantial body of theory, research, and experience provides a wealth of insight into motivation in organizations (Pinder, 2008). Yet in scrutinizing the topic, scholars have increasingly shown its complexity. Everyone has a sense of what we mean by motivation. The term derives from the Latin word for “move,” as do the words motor and motif. We know that forces move us, arouse us, direct us. Work motivation refers to a person’s desire to work hard and work well—to the arousal, direction, and persistence of effort in work settings. Managers in public, private, and nonprofit organizations use motivational techniques all the time. Yet debates about motivation have raged for years, because the simple definition just given leaves many questions about what it means to work hard and well, what determines a person’s desire to do so, and how one measures such behavior.

Measuring and Assessing Motivation

Motivation researchers have tried different ways of measuring motivation, none of which provides an adequately comprehensive measurement (Pinder, 2008, pp. 43–44). For example, the typical definition of motivation, such as the one just provided, raises complicated questions about what we actually mean by motivation. Is it an attitude or a behavior, or both? Must we observe a person exerting effort?

As Exhibit 9.1 shows, researchers have tried to measure motivation in different ways that imply different answers to these questions. As the examples in the exhibit imply, OB researchers have attempted very few measures of general work motivation. One of the few available general measures—section 1 in the exhibit—relies on questions about how hard one works and how often one does some extra work. Researchers have reported successful use of this scale (Cook, Hepworth, Wall, and Warr, 1981). One study using this measure, however, found that respondents gave very high ratings to their own work effort. Most reported that they work harder than others in their organization. They gave such high self-ratings that there was little difference among them (Rainey, 1983). This example illustrates the problem of asking people about their motivation. It also reflects the cultural emphasis on hard work in the United States, which leads people to report that they do work hard. If, however, as in the study just cited, most respondents report that they work harder than their colleagues, there must be organizations in which everyone works harder than everyone else!

Wright (2004) reported the successful use of the questions in section 2 of Exhibit 9.1 in a survey of government employees in New York State. The respondents’ answers to the items were consistent, and the scale containing these items showed meaningful relations to other variables, such as the respondents’ perceptions of the clarity of their work goals and the organization’s goals.

Partly due to the problems with general measures of motivation, researchers have used various alternatives, such as measures of intrinsic or internal work motivation (section 3 in Exhibit 9.1; see also Cook, Hepworth, Wall, and Warr, 1981). Researchers in OB define intrinsic work motives or rewards as those that are mediated within the worker—psychological rewards derived directly from the work itself. Extrinsic rewards are externally mediated and are exemplified by salary, promotion, and other rewards that come from the organization or work group. As the examples in Exhibit 9.1 indicate, questions on intrinsic motivation ask about an increase in feelings of accomplishment, growth, and self-esteem through work well done. Measures such as these assess important work-related attitudes, but they do not ask directly about work effort or direction.

Researchers and consultants have used items derived from expectancy theory, described later in this chapter, as proxy measures of work motivation. Such items (see section 4 in Exhibit 9.1) have been widely used by consultants in assessing organizations and in huge surveys of federal employees used to assess the civil service system and efforts to reform it (U.S. Office of Personnel Management, 1979, 1980, 1983). Surveys have also found sharp differences between government and business managers on questions such as these (Rainey, 1983; Rainey, Facer, and Bozeman, 1995). The U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (2012, p. 37), in a survey of over forty-two thousand federal employees, used questions similar to these and interpreted them as indicators of motivation.

If one cannot ask people directly about their motivation, one can ask those around them for their observations about their coworkers’ motivation (see section 5 in Exhibit 9.1). Landy and Guion (1970) had peers rate individual managers on the dimensions listed in the table. Significantly, their research indicated that peer observers disagree a lot when rating the same person. This method obviously requires a lot of time and resources to administer, and few other researchers have used this very interesting approach. The method does provide a useful illustration of the many possible dimensions of motivation.

Motivation to Join and Motivation to Work Well

Another important consideration about the meaning of motivation concerns one of the classic distinctions in the theory of management and organizations: the difference between motivation to join an organization and stay in it, on the one hand, and motivation to work hard and do well within it, on the other. Chester Barnard (1938), and later James March and Herbert Simon (March and Simon, 1958), in books widely acknowledged as seminal contributions to the field, emphasized this distinction. You might get people to shuffle into work every day rather than quit, but they can display keen ingenuity at avoiding doing what you ask them to do if they do not want to do it. Management experts widely acknowledge Barnard’s prescience in seeking to analyze the ways in which organizational leaders must employ a variety of incentives, including the guiding values of the organization, to induce cooperation and effort (DiIulio, 1994; Peters and Waterman, 1982; Williamson, 1990).

Rival Influences on Performance

Motivation alone does not determine performance. Ability figures importantly in performance. One person may display high motivation but insufficient ability, whereas another may have such immense ability that he or she performs well with little apparent motivation. The person’s training and preparation for a certain task, the behaviors of leaders or coworkers, and many other factors interact with motivation in determining performance. A person may gain motivation by feeling able to perform well, or lose motivation through the frustrations brought on by lacking sufficient ability. Alternatively, a person may lose motivation to perform a task he or she has completely mastered because it fails to provide a challenge or a sense of growth. As we will see, the major theories of employee motivation try in various ways to capture some of these intricacies. The points may sound obvious enough, but major reforms of the civil service and of government pay systems have frequently oversimplified or underestimated these ideas (Ingraham, 1993; Perry, Petrakis, and Miller, 1989; Rainey and Kellough, 2000).

Motivation as an Umbrella Concept

The complexities of work motivation have given the topic the status of an umbrella concept that refers to a general area of study rather than a precisely defined research target (Campbell and Pritchard, 1983; Pinder, 2008). Indeed, Locke (1999), in an article reviewing and summarizing motivation research, proposed an elaborate, integrated model of work motivation that does not include the term motivation. Research and theorizing about motivation continue, but theorists usually employ the term to refer to a general concept that incorporates many variables and issues (see, for example, Klein, 1990; Kleinbeck, Quast, Thierry, and Harmut, 1990). Locke and Latham (1990a), for example, presented a model of work motivation that does not include a concept specifically labeled “motivation.” Motivation currently appears to serve as an overarching theme for research on a variety of related topics, including organization identification and commitment, leadership practices, job involvement, organizational climate and culture, and characteristics of work goals.

Theories of Work Motivation

This chapter reviews the most prominent theories of motivation, which represent theorists’ best efforts to explain motivation and to describe how it works. Some of the terms sound abstract, but the effort is quite practical: How do you explain the motivation of members of your organization and use this knowledge to enhance their motivation? No one has yet developed a conclusive theory of work motivation, but each theory provides important insights about motivation and can contribute to managers’ ability to think comprehensively about it. The examples provided show that reforms in government have often revealed simplistic thinking about work motivation on the part of the reformers—thinking that could be improved by more careful attention to the theories described here.

One way of thinking about theory in the social and administrative sciences regards theory as an explanation of a phenomenon we want to understand, in the present case, work motivation. A theory proposes concepts that refer to objects or events that we need to define and include as contributions to the explanation. The theory also states propositions about how those concepts relate together to bring about the phenomenon. The theories of work motivation, then, attempt to explain how work motivation operates—how and why does it happen? How and why does a person become more highly motivated? In attempting to answer such questions, the following theories provide ideas, concepts, and propositions that can guide our thinking about motivation. They can help to guide research and analysis of motivational phenomena in organizations, as they did in the case of the Merit Principles survey, mentioned earlier (U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, 2012). None of the theories provides a conclusive explanation of work motivation, but each one provides important insights and ideas about how to think about it.

One way of classifying the theories of motivation that have achieved prominence distinguishes between content theories and process theories. Content theories are concerned with analyzing the particular needs, motives, and rewards that affect motivation. Process theories concentrate more on the psychological and behavioral processes behind motivation, often with no designation of important rewards and motives. The two categories overlap, and the distinction need not be taken as confining. It serves largely as a way of introducing some of the major characteristics of the different theories.

Content Theories

Exhibit 9.2 summarizes the needs, motives, and rewards that play a part in prominent content theories of motivation. These theories not only propose the important needs, motives, and rewards, but also attempt to specify how such factors influence motivation.

| Hygiene Factors | Motivators |

| Company policy and administration | Achievement |

| Supervision | Recognition |

| Relations with supervisor | The work itself |

| Working conditions | Responsibility |

| Salary | Growth |

| Relations with peers | Advancement |

| Personal life | |

| Relations with subordinates | |

| Status | |

| Security |

Maslow: Needs Hierarchy.

Abraham Maslow’s theory of human needs and motives (1954), described earlier in Chapter Two, advanced some of the most widely influential ideas in social science. Contemporary scholars of work motivation do not accept the needs hierarchy as a complete theory of motivation, but it contributed concepts that are now regarded as classic. Maslow’s conception of self-actualization as the highest-order human need was his most influential idea. It has appealed widely to people searching for a way to express an ultimate human motive of fulfilling one’s full potential.

In later writings, Maslow (1965) further developed his ideas about self-actualization, going beyond the ideas summarized in Chapter Two and Exhibit 9.2, to discuss the relationship of this motive to work, duty, and group or communal benefits. His ideas are particularly relevant to anyone interested in public service. Maslow was concerned that during the 1960s some psychologists interpreted self-actualization as self-absorbed concern with one’s personal emotional satisfaction, especially through the shedding of inhibitions and social controls. He sharply rejected such ideas. Genuinely self-actualized persons, he argued, achieve this ultimate state of fulfillment through hard work and dedication to a duty or mission that serves values higher than simple self-satisfaction. They do so through work that benefits others or society, and genuine personal contentment and emotional salvation are by-products of such dedication. In this later work, Maslow emphasized that the levels of need are not separate steps from which one successively departs. Rather, they are cumulative phases of a growth toward self-actualization, a motive that grows out of the satisfaction of social and self-esteem needs and also builds on them.

Maslow’s ideas have had a significant impact on many social scientists but have received little reverence from empirical researchers attempting to validate them. Researchers trying to measure Maslow’s needs and test his theory have not confirmed a five-step hierarchy. Instead they have found a two-step hierarchy in which lower-level employees show more concern for material and security rewards and higher-level employees place more emphasis on achievement and challenge (Pinder, 2008).

Critics also point to theoretical weaknesses in Maslow’s hierarchy. Locke and Henne (1986) identified the dubious behavioral implications of Maslow’s emphasis on need deprivation—that is, his contention that unsatisfied needs dominate behavior. Being deprived of a need does not tell a person what to do about it, and the theory does not explain how people know how to respond.

In spite of the criticisms, Maslow’s theory has had a strong following among many other scholars and management experts. Maslow contributed to a growing recognition of the importance of motives for growth, development, and actualization among members of organizations. His ideas also influenced other developments in the social sciences and OB. For example, in a prominent book on leadership, James MacGregor Burns (1978) drew on Maslow’s concepts of a hierarchy of needs and of higher-order needs such as self-actualization. Burns observed that transformational leaders—that is, leaders who bring about major transformations in society—do not engage in simple exchanges of benefits with their followers. Rather, they appeal to higher-order motives in the population, including motives for self-actualization that are tied to societal ends, involving visions of a society transformed in ways that fulfill such personal motives. As a political scientist, Burns concentrated on political and societal leaders, but writers on organizational leadership have acknowledged his influence on recent thought about transformational leadership in organizations (see Chapter Eleven). In addition, Maslow’s work foreshadowed and helped to shape current discussions of organizational mission and culture, worker empowerment, and highly participative forms of management (see, for example, Lawler, 2003; Peters and Waterman, 1982).

McGregor: Theory X and Theory Y.

Douglas McGregor’s ideas about Theory X and Theory Y (1960) also reflected the influence of Maslow’s work and the penetration into management thought of an emphasis on higher-order needs. As described in Chapter Two, McGregor argued that industrial management in the United States has historically reflected the dominance of a theory of human behavior that he calls Theory X, which assumes that workers lack the capacity for self-motivation and self-direction and that managers must design organizations to control and direct them. McGregor called for wider acceptance of Theory Y, the idea that workers have needs like those Maslow described as higher-order needs—for growth, development, interesting work, and self-actualization. Theory Y should guide management practice, McGregor argued. Managers should use participative management techniques, decentralized decision making, performance evaluation procedures that emphasize self-evaluation and objectives set by the employee, and job enrichment programs to make jobs more interesting and responsible. Like Maslow’s, McGregor’s ideas have had profound effects on the theory and practice of management. Chapter Thirteen describes two examples of efforts to reform and change federal agencies that drew on McGregor’s ideas about Theory Y.

Herzberg: Two-Factor Theory.

Frederick Herzberg’s two-factor theory (1968) also emphasized the essential role of higher-order needs and intrinsic incentives in motivating workers. From studies involving thousands of people in many occupational categories, he and his colleagues concluded that two major factors influence individual motivation in work settings. They called these factors hygiene factors and motivators (see Exhibit 9.2). Insufficient hygiene factors can cause dissatisfaction with one’s job, but even when they are abundant they do not stimulate high levels of satisfaction. As indicated in Exhibit 9.2, hygiene factors are extrinsic incentives—including organizational, group, or supervisory conditions—or externally mediated rewards such as salaries. Hygiene factors can only prevent dissatisfaction, but motivators are essential to increasing motivation. They include intrinsic incentives such as interest in and enjoyment of the work itself and a sense of growth, achievement, and fulfillment of higher-order needs.

Herzberg concluded that because motivators are the real sources of stimulation and motivation for employees, managers must avoid the negative techniques of controlling and directing employees and should instead design work to provide for the growth, achievement, recognition, and other elements people need, which are represented by the motivators. This approach requires well-developed job enrichment programs to make the work itself interesting and to give workers a sense of control, achievement, growth, and recognition, which produces high levels of motivation.

Herzberg’s work sparked controversy among experts and researchers. He and his colleagues developed their evidence by asking people to describe events on the job that led to feelings of extreme satisfaction and events that led to extreme dissatisfaction. Most of the reports of great satisfaction mentioned intrinsic and growth factors. Herzberg labeled these motivators in part because the respondents often mentioned their connection to heightened motivation and better performance. Reports of dissatisfaction tended to concentrate on the hygiene factors.

Researchers using other methods of generating evidence did not obtain the same results, however (Pinder, 2008). Critics argued that when people are asked to describe an event that makes them feel highly motivated, they might hesitate to report such things as pay or an improvement in physical working conditions. Instead, in what social scientists call a social desirability effect, they might attempt to provide more socially acceptable answers. Critics also questioned Herzberg’s conclusions about the effects of the two factors on individual behavior. These concerns about the limitations of the theory led to a decline in interest in it. Locke and Henne (1986), for example, found no recent attempts to test the theory and concluded that theorists no longer took it seriously. Nevertheless, the theory always receives attention in reviews of motivation theory because of its contribution to the stream of thought about such topics as “job enrichment” and restructuring work to make it interesting and to satisfy workers’ needs for growth and fulfillment. Thus the theory continues to contribute to contemporary thinking about motivating people in organizations.

McClelland: Needs for Achievement, Power, and Affiliation.

In its day, David McClelland’s theory (1961) about the motivations for seeking achievement, power, and affiliation (friendly relations with others)—especially his ideas about the need for achievement—was one of the most prominent theories in management and OB. It elicited thousands of studies (Locke and Henne, 1986; McClelland, 1961). Need for achievement (n Ach), the central concept in his theory, refers to a motivation—a “dynamic restlessness” (McClelland, 1961, p. 301)—to achieve a sense of mastery over one’s environment through success at achieving goals by using one’s own cunning, abilities, and efforts. McClelland originally argued that n Ach was a common characteristic of persons attracted to managerial and entrepreneurial roles, although he later narrowed its application to predicting success in entrepreneurial roles (Pinder, 2008).

McClelland measured n Ach through a variety of procedures, including the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT). The TAT involves showing a standard set of pictures to individuals, who then make up brief stories about what is happening in each picture. One typical picture shows a boy sitting at a desk in a classroom reading a book. A respondent identified as low in n Ach might write a story about the boy daydreaming, while someone high in n Ach might write a story about the boy studying hard to do well on a test. Researchers have also measured n Ach through questionnaires that ask about such matters as work role preferences and the role of luck in outcomes.

McClelland (1961) argued that persons high in n Ach are motivated to achieve in a particular pattern. They choose fairly challenging goals with moderate risks, for which outcomes are fairly clear and accomplishment reflects success through one’s own abilities. Persons in roles such as research scientist, which requires waiting a long time for success and recognition, may have a motivation to achieve, but they do not conform to this pattern. As one example of the nature of n Ach motives, McClelland cited the performance of students in experiments in which they chose how to behave in games of skill. The researchers had the students participate in a ring-toss game. The participants chose how far from the target peg they would stand. The high–n Ach participants tended to stand at an intermediate distance from the peg, not too close but not too far away. McClelland interpreted this choice as a reflection of their desire to achieve through their own skills. Standing too close made success too easy and thus did not satisfy their desire for a sense of accomplishment and mastery. Standing too far away, however, made success a gamble, a matter of a lucky throw. The high–n Ach participants chose a distance that would likely result in success brought about by the person’s own skills. McClelland also offered evidence of other characteristics of persons with high n Ach, such as physical restlessness, particular concern over the rapid passage of time, and an aversion to wasting time.

McClelland claimed that measuring n Ach could determine the success of individuals in business activities and the success of nations in economic development (McClelland, 1961; Pinder, 2008). He analyzed the achievement orientation in the folktales and children’s stories of various nations and produced some evidence that cultures high in n Ach themes also showed higher rates of economic development. He has also claimed successes in training managers in business firms in less developed countries to increase their n Ach and enhance the performance of their firm (McClelland and Winter, 1969). McClelland suggested achievement-oriented fantasizing and thinking as a means to improving the economic performance of nations. Others have also reported the use of achievement motivation training with apparent success in enhancing motivation and increasing entrepreneurial behaviors (Miner, 2005).

McClelland (1975) later concluded that n Ach encouraged entrepreneurial behaviors rather than success in managerial roles. He argued, however, that his conceptions of the needs for power and affiliation did apply in predicting success in management roles (although there is much less empirical research about these needs to support his claims). McClelland concluded that the most effective managers develop high motivation for power, but with an altruistic orientation and a concern for group goals. This stage also involves a low need for affiliation, however, because too strong a need for friendship with others can hinder a manager.

Reviewers vary in their assessments of the state of this theory. Some rather positive assessments contrast with others that focus only brief attention on it (Pinder, 2008) or criticize it harshly. Locke and Henne (1986) condemned the body of research on the theory as chaotic. Miner (2005), however, evaluates the theory as high on validity and usefulness, and importance. Miner points out that McClelland’s work had a variety of influences on managerial development practices, including such procedures as “competency modelling.”

McClelland’s theory adds another important element to a well-developed perspective on motivation. Individuals vary in the general level and pattern of internal motivation toward achievement and excellence that they bring to work settings. These differences suggest the importance of employee selection in determining the level of motivation in an organization, but also the importance of designing conditions to take advantage of these patterns of motivation.

Adams: Equity Theory.

J. Stacy Adams (1965) argued that a sense of equity in contributions and rewards has a major influence on work behaviors. A sense of inequity brings discomfort, and people therefore act to reduce or avoid it. They assess the balance between their inputs to an organization and the outcomes or rewards they receive from it, and they perceive inequity if this balance differs from the balance experienced by other employees. For example, if another person and I receive the same salary, recognition, and other rewards, yet I feel that I make a superior contribution by working harder, producing more, or having more experience, I will perceive a state of inequity. Conversely, if the other person makes superior inputs but gets lower rewards than I get, I will perceive inequity in the opposite sense; I will feel overcompensated.

In either case, according to Adams, a person tries to eliminate such inequity. If people feel overcompensated, they may try to increase their inputs or reduce their outcomes to redress the inequity. If they feel undercompensated, they will do the opposite, slowing down or reducing their contributions. Adams advanced specific propositions about how workers react that depend on factors such as whether they receive hourly pay or are paid according to their rate of production. For example, he predicted that if workers are overpaid on an hourly basis, they will produce more per hour, to reduce the feeling that they are overcompensated. If they are overpaid on a piece-rate basis, however, they will slow down, to avoid making more money than other workers.

These sorts of predictions have received some confirmation in laboratory experiments. The theory proves difficult to apply in real work settings, however, because it is hard to measure and assess inequity, and some of the concepts in the theory are ambiguous (Miner, 2005). People vary in their sensitivity to inequity, and they may vary widely in how they react to the same conditions.

Regardless of the success of this particular theory, equity in contributions and rewards figures very importantly in management. As described later, more recent models of motivation include perceptions about equity as important components. Equity issues also play a role in debates about civil service reforms and performance-based pay plans in the public sector. Governments at all levels in the United States and in other countries have tried to adopt performance-based pay plans. Supporters of such plans have often cited equity principles akin to those stressed in this theory. They have argued that people who perform better than others but receive no better pay perceive inequity and experience a loss of morale and motivation, and that the highly structured pay and reward systems in government tend to create such situations. The more recently popular alternative involves broadbanding or paybanding systems. In these systems, a larger number of pay grades and pay steps within those grades are collapsed into broader bands or categories of pay levels. Better performers can be more rapidly moved upward in pay within these bands, rather than having to go through the previous, more elaborate set of grades and steps one at a time. People promoting and designing these plans also point to pay equity as a major justification for such plans. For example, the Internal Revenue Service implemented a carefully developed paybanding system for their middle managers, in part because some of these managers had commented in focus group sessions that they felt demoralized when they worked and tried very hard but received the same pay raises as other managers who did so little that they were “barely breathing” (Thompson and Rainey, 2003).

Equity theory has influenced a stream of research on justice in organizations (Greenberg and Cropanzano, 2001). This research examines employees’ perceptions of two types of justice in organizations. Distributive justice in organizations concerns the fairness and equity in distribution of rewards and resources. Procedural justice concerns the fairness with which people feel they and others are treated in organizational processes, such as decision making that affects them, layoffs, or disciplinary actions. For example, are they given a chance to have hearings about such decisions?

In general, researchers have found that perceptions of higher levels of justice in organizations tend to relate to positive work-related attitudes such as work satisfaction and satisfaction with supervision and leadership. Kurland and Egan (1999) compared perceptions of organizational justice on the part of public employees in two city agencies to those of employees in seven business firms. The public employees perceived lower levels of procedural and distributive justice than the private employees did. For the public employees, higher levels of perceived distributive and procedural justice were related to higher satisfaction with supervisors. For the private employees, only higher levels of procedural justice were related to higher satisfaction with supervisors. Lee and Shin (2000), conversely, compared employees in public and private R&D organizations in Korea and found no differences between the two groups in perceptions of procedural justice, but the public employees perceived less distributive justice in relation to pay.

For most managers, trying to ensure that people feel they are rewarded fairly in comparison to others is a major responsibility and challenge. A manager often finds it easier to rely heavily on the most energetic and competent people than to struggle with the problem of dealing with less capable or less enthusiastic ones. If a manager cannot or does not appropriately reward those on whom he or she places heavier burdens, these more capable people can become frustrated. Managers in government organizations commonly complain that the highly structured reward systems in government aggravate this problem. In work groups and team-based activities, too, the problem of a team member’s not contributing as well as others can raise tensions. Many of the motivational techniques described later in this chapter, and the leadership and cultural issues discussed in the next chapter, pertain to the challenge of maintaining equity in the work setting.

Process Theories

Process theories emphasize how the motivational process works. They describe how goals, values, needs, or rewards operate in conjunction with other factors to determine motivation. The content factors—the particular needs, rewards, and so on—are not specified in the theories themselves.

Expectancy Theory.

Expectancy theory states that an individual considering an action sums up the values of all the outcomes that will result from the action, with each outcome weighted by the probability of its occurrence. The higher the probability of good outcomes and the lower the probability of bad ones, the stronger the motivation to perform the action. In other words, the theory draws on the classic utilitarian idea that people will do what they see as most likely to result in the most good and the least bad.

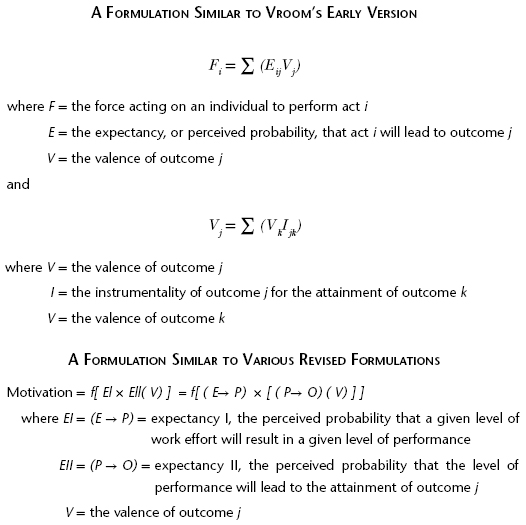

Although the theory draws on classic utilitarian ideas, it assumed an important role in contemporary OB theory. Vroom (1964) stated the theory formally, with algebraic formulas (see Figure 9.1). The formula expresses the following idea: the force acting on an individual and causing him or her to work at a particular level of effort (or to choose to engage in a particular activity) is a function of the sum of the products of the perceived desirability of the outcomes associated with working at that level (or the valences) and the expectancies for the outcomes. Expectancies are the person’s estimates of the probability that the expected outcomes will follow from working at a particular level. In other words, multiply the value (positive or negative) of each outcome by the expectancy (perceived probability) that it will occur, and sum these products for all the outcomes. A higher sum reflects higher expectancies for more positively valued outcomes and should predict higher motivation.

FIGURE 9.1. FORMULATIONS OF EXPECTANCY THEORY

Researchers originally hoped that this theory would provide a basis for the systematic research and diagnosis of motivation: ask people to rate the positive or negative value of important outcomes of their work and the probability that desirable work behaviors would lead to those outcomes or avoid them, and use the expectancy formula to combine these ratings. They hoped that this approach would improve researchers’ ability to predict motivational levels and analyze good and bad influences on them, such as problems due to beliefs that certain outcomes were unattainable or that certain rewards offered little value. A spate of empirical tests soon followed, with mixed results. Some of the studies found that the theory failed to predict effort and productivity. Researchers began to point out weaknesses in the theory (Pinder, 2008, pp. 376–383). For example, they complained that it did not accurately represent human mental processes, because it assumed that humans make exhaustive lists of outcomes and their likelihoods and sum them up systematically.

Nevertheless, expectancy theory still stands as one of the most prominent work motivation theories. Researchers have continued to propose various improvements in the theory, and to seek to integrate it with other theoretical perspectives (for example, Steel and Konig, 2006). Some versions relax the mathematical formula and simply state that motivation depends generally on the positive and negative values of outcomes and their probabilities, in ways we cannot precisely specify (see Figure 9.1). Some of these more recent forms of the theory have broken down the concept of expectancies into two types, as illustrated in the figure. Expectancy I (EI) perceptions reflect an individual’s beliefs about the likelihood that effort will lead to a particular performance level. Expectancy II (EII) perceptions reflect the perceived probability that a particular performance level leads to a given level of reward. The distinction helps to clarify some of the components of motivational responses.

As an example of applying the theory, the Performance Management and Recognition System (PMRS), one of the many pay-for-performance plans adopted by governments during the 1980s, applied to middle managers in federal agencies (General Schedule salary levels 13–15). Under PMRS, a manager’s superior would rate the manager’s performance on a five-point scale, and the manager’s annual salary increase would be based on that rating. PMRS got off to a bad start in many federal agencies, however. In some agencies, the vast majority of the managers received very high performance ratings and their EI perceptions strengthened. It became clear that they had a high likelihood of performing well enough to receive a high rating. Yet about 90 percent of the managers in some agencies received pay raises of 3 percent or less, and fewer than 1 percent received pay raises of as much as 10 percent. EII perceptions, then, naturally weaken. One may expect to perform well enough to get a high rating (EI), but performance at that level may not lead to a high probability of getting a significant reward (EII). PMRS, like many other performance-based pay plans in government, applies expectancy theory implicitly but fails to do so adequately (Perry, 1986; Perry, Petrakis, and Miller, 1989). Soon after its introduction, PMRS was canceled. The fundamental problem persists, moreover, in performance evaluation systems in the public and private sectors. For example, officials of the U.S. Office of Personnel Management have repeatedly pointed out that a very high percentage of the members of the Senior Executive Service (SES) received the highest performance rating. (The SES consists of the highest ranks of career executives in the U.S. federal civil service.) They have called on the executives who gave these ratings to do more to make distinctions among the performance levels of the people they evaluated.

Analysts at the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (2012, p. 37) used a version of the theory similar to this latter version to develop proposals for enhancing motivational conditions in federal agencies. Using the responses to their survey, mentioned earlier, they calculated a “motivation force” statistic for each of a set of rewards the questionnaire asked respondents to rate as to the reward’s attractiveness. The motivation force statistic was the product of the respondent’s responses to questions measuring the extent to which (1) effort leads to performance, (2) performance leads to the particular reward, and (3) the reward is desirable. The motivation force statistic related positively to respondents’ performance ratings.

Some recent versions of the theory also draw in other variables. They point out, for example, that a person’s self-esteem can affect EI perceptions. Organizational characteristics and experiences, such as the characteristics of the pay plan or the perceived equity of the reward system, can influence EII perceptions—as in the PMRS case. Some of the most recent versions bring together expectancy concepts with ideas about goal setting, control theory, and social learning theory, discussed in the following sections (Latham, 2007, p. 260; Steel and Konig, 2006). These examples show how recent formulations of the theory provide useful frameworks for analyzing motivational plans and pinpointing the sources of problems.

Operant Conditioning Theory and Behavior Modification.

Another body of research that has influenced motivation theory and practice and that has implications similar to those of expectancy theory applies operant conditioning and behavior modification concepts to the management of employees. This approach draws on the theories of psychologists such as B. F. Skinner, who argued that we can best analyze behavior by studying the relationships between observable behaviors and contingencies of reinforcement.

The term operant conditioning stems from a revision Skinner (1953) and others made to older versions of stimulus-response psychology. Skinner pointed out that humans and animals do not develop behaviors simply in response to stimuli. We emit behaviors as well, and those behaviors operate on our environment, generating consequences. We repeat or drop behaviors depending on the consequences. We acquire behaviors or extinguish them in response to the conditions or contingencies of reinforcement.

A reinforcement is an event that follows a behavior and changes the probability that the behavior will recur. (We might call this a reward or punishment, but Skinner apparently felt that the term reinforcement was a more objective one, because it assumes less about what goes on inside the subject.) Learning and motivation depend on schedules of reinforcements, referring to how regularly they follow a particular behavior. For example, a manager can praise an employee every time he or she does good work, such as completing a task on time, or the manager can praise the behavior once out of every several times it occurs. According to the operant conditioning perspective, such variations make a lot of difference.

Operant theory derives from what psychologists have called the behaviorist school of psychology. Behaviorism gained its label because it emphasizes observations of the overt behaviors of animals and humans without hypothesizing about what goes on inside them. In a classic debate in psychology, some theorists (the precursors to the expectancy theorists) argued that motivation and learning theories should refer to what goes on inside the organism. Behaviorists, such as Skinner, rejected the use of such internal constructs, arguing that because one cannot observe them scientifically, they can only add confusing speculation to the analysis of motivation. Skinner argued that one can scientifically analyze only those behaviors that are overtly observable. In recent years psychologists have worked toward reconciling operant behaviorism with cognitive concepts (Bandura, 1978, 1997; Bandura and Locke, 2003; Kreitner and Luthans, 1987; Pinder, 2008, pp. 455–473).

Skinner and other behaviorists analyzed relationships between reinforcements and behaviors and developed principles related to various types and schedules of reinforcement. For example, Skinner pointed out that a subject acquires a behavior more rapidly under a constant reinforcement schedule, but the behavior will extinguish (stop occurring) faster than one brought about using a variable-ratio schedule. Accordingly, the behaviorists would suggest that constant praise by a supervisor might have more immediate effects on the employee than intermittent praise, but the effects would fall off rapidly if the manager stopped the constant praise. Intermittent praise might be slower to take effect, but it would last longer. Behaviorists also point out that positive reinforcement works better than negative reinforcement or punishment. Exhibit 9.3 summarizes the concepts and principles from this body of theory.

Behavior modification refers to techniques that apply principles of operant conditioning to modify human behavior. The term apparently comes from the way in which the behaviorists studied the principles of reinforcement, by modifying and shaping behaviors. They would, for example, develop a behavior by reinforcing small portions of it, then larger portions, and so on, until they developed the full behavior (for example, inducing an anorexic patient to eat by first reinforcing related behaviors such as picking up a fork, and then eating a small amount, and so on).

Behavior modification has come to refer broadly and somewhat vaguely to a wide variety of techniques for changing behaviors, such as programs for helping people to stop smoking. Some of these techniques adhere closely to behaviorist principles; others may have little to do with them. Behavior modification practitioners claimed successes in psychological therapy, improvement of student behavior and performance in schools, supervision of mentally retarded patients, and rewarding the attendance of custodial workers (Bandura, 1969; Sherman, 1990). Many organizations, including public ones such as garbage collection services, have adopted variants of these techniques to improve performance and productivity.

As these examples show, managers and consultants have applied behavior modification techniques in organizations. The ideas about intermittent schedules just mentioned and noted in Exhibit 9.3, for example, lead some behavior modification proponents (Kreitner and Luthans, 1987) to prescribe such managerial techniques as not praising a desired behavior constantly. They advise praise on a varying basis, after a variable number of repetitions of the behavior. They might also prescribe periodic bonuses to supplement a worker’s weekly paycheck, arguing that the regular check will lose its reinforcing properties over time but the bonuses will act as variable-interval reinforcements, strengthening the probability of sustained long-term effort. They have also offered useful suggestions about incremental shaping of behaviors by reinforcing successively larger portions of a desired behavior.

These kinds of prescriptions provide examples of those offered by practitioners of organizational behavior modification (OB Mod). OB Mod often involves this approach:

A number of field studies of such projects have reported successes in improving employee performance, attendance, and adherence to safety procedures (Miner, 2006; Pinder, 2008, 448ff.). A highly successful effort by Emery Air Freight, for example, received widespread publicity (Kreitner and Luthans, 1987). The project involved having employees monitor their own performance, setting performance goals, and using feedback and positive reinforcements such as praise and time off.

Yet controversy over explanations of the success of this project reflects more general controversies about OB Mod. Critics have argued that the success of the Emery example, as well as other applications of OB Mod, was not the result of the use of operant conditioning principles. These practices succeeded, according to the critics, because they included such steps as setting clear performance goals and making rewards contingent upon them (Locke, 1977). Therefore, the critics contend, these efforts do not offer any original insights derived from OB Mod. One might draw similar conclusions from expectancy theory, for example. Other criticisms focus on the questionable ethics of the emphasis on manipulation and control of people. Also, behavior modification and OB Mod appear to be most successful in altering relatively simple behaviors that are amenable to clear measurement. Even then, the techniques often involve practical difficulties, because of all the measuring and reinforcement scheduling required.

In response to criticisms, however, proponents of OB Mod, and of behavior modification more generally, pointed to the successes of the techniques. They counter attacks on the ethics of their approach by arguing that they cut through a lot of obfuscating fluff about values and internal states and move right to the issue of correcting bad behaviors and augmenting good ones. (“Do you want smokers to be able to stop, anorexics to eat, and workers to follow safety precautions, or do you not?”) Similarly, OB Mod advocates claim that their approach succeeds in developing a focus on desired behaviors (getting the filing clerk to come to work on time), as opposed to making attributions about attitudes (“The filing clerk has a bad attitude”), and an emphasis on strategies for positive reinforcement of desired behaviors (Kreitner and Luthans, 1987; Stajkovic and Luthans, 2001).

Social Learning Theory.

Social learning theory reflects both the limitations and the value of operant conditioning theory and OB Mod. Developed by psychologist Albert Bandura (1978, 1989, 1997) and others, social learning theory—and later, “social cognitive theory” (Bandura, 1986)—blends ideas from operant conditioning theory with greater recognition of internal cognitive processes such as goals and a sense of self-efficacy, or personal effectiveness. It gives attention to forms of learning and behavior change that are not tightly tied to some external reinforcement.

For example, individuals obviously learn by modeling their behaviors on those of others and through vicarious experiences. Humans also use anticipation of future rewards, mental rehearsal and imagery, and self-rewarding behaviors (such as praising oneself) to influence their own behavior. Applications of such processes in organizational settings have included frameworks for developing leadership and self-improvement, and studies have suggested that the sorts of techniques just mentioned can improve performance. For example, Sims and Lorenzi (1992) proposed models and methods for motivating oneself and others through self-management that make use of some of the techniques just suggested—such as setting goals for oneself and developing the capacity of others to set their own goals, developing self-efficacy in oneself and others, and employing modeling and self-rewarding behaviors (such as self-praise). Sims and Lorenzi proposed that this approach can support the development of more decentralized, participative, empowering leaders and teamwork processes in organizations.

Goal-Setting Theory.

Psychologists Edwin Locke, Gary Latham, and their colleagues have advanced a theory of goal setting that has been very successful in that it has been solidly confirmed by well-designed research (Latham, 2007; Locke, 2000; Locke and Latham, 1990a; Miner, 2005; Pinder, 2008, pp. 389–422). The theory states that difficult, specific goals lead to higher performance than easy goals, vague goals, or no goals (for example, “Do your best”). Difficult goals enhance performance by directing attention and action, mobilizing effort, increasing persistence, and motivating the search for effective performance strategies. Commitment to the goals and feedback about progress toward achieving them are also necessary for higher performance. Commitment and feedback do not by themselves stimulate high performance without difficult, specific goals, however. Research findings also indicate that although participation in setting a goal does not enhance commitment to it, expecting success in attaining the goal does enhance commitment.

Locke and Latham (1990b) contended that assigning difficult, specific goals enhances performance because of the goals’ influence on an individual’s personal goals and his or her self-efficacy. Self-efficacy refers to a person’s sense of his or her capability or effectiveness in accomplishing outcomes (Bandura, 1989). Assigned goals influence personal goals through a person’s acceptance of and commitment to them. They influence self-efficacy by providing a sense of purpose and standards for evaluating performance, and they create opportunities for accomplishing lesser and proximal goals that build a sense of self-efficacy (Earley and Lituchy, 1991).

Although many studies support this theory, another reason for its success may be its compactness and relatively narrow focus (Pinder, 2008). The theory and much of the research that supports it concentrate on task performance in clear and simple task settings, which is amenable to the setting of specific goals. Also, a few studies have examined complex task settings (Locke and Latham, 1990a). However, some of the prominent contributions to organization theory in recent decades, such as the contingency theory and garbage can models of decision making (described in previous chapters), have emphasized that in many situations clear, explicit goals are quite difficult to specify. This suggests that in many of the most important settings, such as high-level strategy development teams, clear, specific goals may be impossible, or even dysfunctional. Similarly, precise goals can raise potential problems for public organizations, given their complex goal sets.

Nevertheless, this body of research emphasizes the value of clear goals for work groups. Whether or not it applies precisely to higher-level goals for public agencies, developing reasonably clear goals remains one of the major responsibilities and challenges for public executives and managers. This is turn raises the interesting question of whether this will be a nearly impossible challenge, given the frequent observations about vague goals in the public sector, mentioned earlier. The literature on public management, however, now offers numerous examples of leaders in public agencies who have developed effective goals (Allison, 1983; Behn, 1994; DiIulio, 1990; Moore, 1990). In addition, Wright (2001) proposed a model of the motivation of government employees that emphasizes both goal-setting theory and social learning theory. He has also reported results of a survey of state government employees in New York State that show relations between goal concepts such as greater work goal clarity and self-reported work motivation (Wright, 2004).

Jung (2013) reports evidence that federal programs that state clearer goals have higher levels of employee satisfaction. He analyzed programs’ reports that were required for the federal government’s Performance Assessment and Rating Tool process, that evaluated the performance of a very large number of federal programs. He developed methods for assessing the clarity of the goals that the programs stated in their reports, and found that programs with clearer goal statements have higher levels of employee satisfaction.

Taylor (2013) reports a study of Australian federal government employees, and their perceptions of goal specificity, goal difficulty, psychological empowerment, and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). She found that goal specificity and difficulty had positive effects on OCB and psychological empowerment.

Latham, one of the two primary authors of goal-setting theory, with colleagues, addressed the matter of whether goal-setting theory can apply in the public sector (Latham, Borgogni, and Pettita, 2008). The authors acknowledge the claims that organizational goals tend to be vague in the public sector. They note that research shows that organizational goal ambiguity varies among federal agencies but that many of them show high levels of goal ambiguity. Yet they provide evidence from an Italian local government setting that goal clarification can have very beneficial effects. The authors suggest the possibility that goal setting may be more often applicable at local levels of government. In general, though, the study supports the conclusion that goal-setting theory can apply in many governmental settings in many nations.

These developments in research suggest that, in spite of the frequent observations that government organizations and programs have vague goals, there are many situations in government in which stating clear goals can have beneficial results. There are many examples, spanning decades, that show that inappropriate, premature, or excessive goal clarification in government programs can have bad effects (for example, Blau, 1969). A careful look at the evidence just described, however, indicates that leaders in government should be aware of goal-setting theory and should invest in appropriate goal clarification.

Recent Directions in Motivation Theory

As mentioned earlier, no theory has provided a conclusive general explanation of work motivation, and reviewers tend to agree that motivation theory is in a disorderly state (for example, Locke and Latham, 2004; Pinder, 2008, p. 484; Steel and Konig, 2006). Authors have tried to integrate the theories just described (for example, Katzell and Thompson, 1990; Latham, 2007, p. 260; Steel and Konig, 2006). For the time being, however, motivation theory remains a body of interesting and valuable, but still fragmented, efforts to apprehend a set of phenomena too complex for any single theory to capture.

Motivation Practice and Techniques

The state of motivation theory just described confronts both managers and researchers with the problem of what to make of it. The theorists lament their inability to provide a universal, conclusive work motivation theory, but that is quite a demanding standard. As illustrated earlier by the use of expectancy theory to analyze the PMRS and the use of motivation theory by the Merit System Protection Board, the individual theories provide useful frameworks for thinking about motivation and developing means of increasing it. Taken together, they make up a valuable framework for analyzing motivational issues in practical settings. The content theories remind us of the importance of intrinsic incentives and equity and provide concepts for expressing them. This may seem obvious enough, but civil service and pay reforms in government in the past several decades have concentrated heavily on extrinsic incentives, to the virtual exclusion of the intrinsic incentives the content theorists emphasize.

Expectancy and operant conditioning theories emphasize an analysis of what is rewarded and punished in organizations and work settings. Kerr (1989), in an article now considered a classic, pointed out that leaders in organizations very frequently fail to reward the behaviors they say they want and in fact reward those they say they do not want. The theories just discussed provide concepts and suggestions for analyzing such reward practices. The theories direct attention to rewards and disincentives rather than to dubious assumptions or attributions about a person’s reasons for behaving as he or she does.

Also, in spite of the travails of the theorists, organizations need motivated members, and they address this challenge in numerous ways. Exhibit 9.4 provides a description of many of the general techniques used to motivate employees, several of which have a large literature devoted to them. Real-world practice often loosely reflects theory, stressing pragmatism instead. Far from making theory irrelevant, however, the practices of organizations often justify the apparently obvious advice of the theorists and experts, because organizations frequently have trouble achieving desirable motivational strategies on their own (Kerr, 1989). For example, surveys find that fewer than one-third of employees in organizations feel that their pay is based on performance (Katzell and Thompson, 1990). As illustrated in the earlier example about PMRS, these techniques often involve implicit motivational assumptions and theories that could be improved through more careful analysis.

Incentive Structures and Reward Expectancies in Public Organizations

The challenge of tying rewards, especially extrinsic rewards, to performance is even greater in many public organizations than it is in private ones. Chapter Eight described numerous studies that demonstrate that organizations under government ownership in many nations usually have more highly structured, externally imposed personnel procedures than private organizations have (for example, Truss, 2013). The civil service systems and centralized personnel systems in government jurisdictions apparently account for these effects.

Of course, public organizations also vary among themselves in how much such systems affect them. The U.S. General Accounting Office, for example, has a relatively independent personnel system and uses a pay-for-performance plan. Government enterprises often have greater autonomy in their personnel procedures than typical government agencies. Some government agencies have adopted paybanding systems (Thompson, 2007), with apparent success. Such examples contribute to a continuing debate over whether pay and other personnel system constraints are an inherent feature of government. Significantly, the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 (Pfiffner and Brook, 2000) sought to loosen the constraints on pay and other personnel rules and procedures in the federal government, but then about fifteen years later the Clinton administration’s National Performance Review (Gore, 1993) launched still another initiative to decentralize federal personnel rules, including those governing pay and other incentives. The U.S. Office of Personnel Management (2001) has for years sought to provide flexibilities in the rules and procedures of the federal system, yet federal managers still call for more of them (Rainey, 2002). While the debate continues, the evidence indicates that at present public organizations more often have more formalized, externally imposed personnel systems than private organizations do.

This evidence of more formalized personnel rules does not in itself prove that people in public organizations perceive them as such. Chapter Eight also described surveys revealing that public managers, in comparison with their private sector counterparts, report more formalized personnel procedures and greater structural constraints on their authority to administer extrinsic rewards such as pay, promotion, and discipline, and to base these on performance (Elling, 1986; Feeney and Rainey, 2011; U.S. Office of Personnel Management, 1979, 1980, 1983, 2013).

The perceptions of the public managers in these studies may reflect shared stereotypes. Business managers may have personnel problems that are just as serious as those faced by public sector managers, despite the stereotype of a stronger relationship between rewards and performance in private business than in government. Interestingly, the U.S. Office of Personnel Management (1999) issued a report about a study that found no evidence that federal agencies have lower discharge rates than private firms, and little evidence that an inordinate number of poor performers remain employed in the federal service. Even if that is the case, these findings indicate that the perception among public managers of having greater difficulty with such matters currently forms part of the culture at all levels of government in the United States.

The existence of formalized personnel systems and managers’ perceptions of constraints under them do not prove that public employees see no connection between extrinsic rewards and their performance. For years, expert observers (Thompson, 1975) have pointed out that some public managers find ways around formal constraints on rewards by isolating poor performers, giving them undesirable assignments, or establishing linkages between rewards and performance in other ways. The motivation theories repeatedly make the point that pay and fear of being fired are often not the best motivators. There are alternative forms of motivation in the public service, including motivation to engage in public service and to pursue important public missions (for example, Goodsell, 2011).

Nevertheless, a number of surveys have indicated that public employees perceive weaker relationships among performance and pay, promotion, and disciplinary action than private employees do (Coursey and Rainey, 1990; Feeney and Rainey, 2011; Lachman, 1985; Porter and Lawler, 1968; Rainey, 1979, 1983; Rainey, Traut, and Blunt, 1986; Solomon, 1986; U.S. Office of Personnel Management, 2013). These studies used expectancy-theory questionnaire items about such relationships and found that public sector samples rated them as weaker. Similarly, the OPM surveys (U.S. Office of Personnel Management, 1979, 2013) have found that sizable percentages of federal employees feel that pay, promotion, and demotion do not depend on performance. Again, these results may reflect shared stereotypes. In fact, there are some conflicting findings. Analysts in the OPM compared results from their survey question about pay and performance with results from a similar item on a large survey of private sector workers; they found little difference in the percentages of employees who expect to get a pay raise for good performance.

Self-Reported Motivation Among Public Employees