CHAPTER FOURTEEN

ADVANCING EFFECTIVE MANAGEMENT IN THE PUBLIC SECTOR

Public organizations perform crucial functions, and it is imperative that they perform them effectively. All of the previous chapters have in some way described possibilities for effective management of public organizations. This chapter covers some more summative approaches to the topic, including general issues about the performance of public organizations, and reviews profiles of well-performing organizations in both the private and public sectors. It then reviews some recent trends in management reform and the pursuit of high performance that have had important influences on public management. Finally, the chapter explores one of the most prominently discussed and frequently employed strategies for enhancing the performance of government—privatization of governmental services, especially through contracting out. Despite its long history of use in government, proponents of privatization still propose it as an innovative solution for public organizations. The main objective of this section, however, is not to analyze privatization. Primarily, it illustrates ways in which the topics and ideas from the framework for organizational analysis presented in Figures 1.1 and 1.2, as elaborated in the previous chapters, can be brought to bear in pursuing new (or renewed) alternatives in public management. It attempts to illustrate a systematic approach to organizing and managing in order to confront a task such as establishing a well-organized approach to privatization, or many other imperatives and challenges that people in public organizations must effectively manage.

The Performance of Public Organizations

Criticism of government and its components, such as government officials, organizations, and employees, is a thriving industry in the United States and in many other nations that allow freedom of expression. Many people make their living in whole or in part in this industry, and virtually all citizens contribute to it in some way. Like other industries, it creates problems, such as information pollution—that is, distortions and excesses in reporting and analysis of government. At the same time, it is an absolutely crucial industry, because we control government in part by scrutinizing and criticizing it. This industry also illustrates the point that the history and culture of the United States have in many ways drawn on the fundamental assumption that public organizations are beset with performance problems, such as red tape and inefficiency, whereas private business firms perform more efficiently and effectively. This assumption is widespread but not universal: surveys show that a majority of Americans share it, but not all (see, for example, Light, 2002a; Lipset and Schneider, 1987; Partnership for Public Service, 2008). Surveys have also found that some Americans are suspicious of private business but have a strong, deep-seated support for—if not confidence in—their government’s institutions (Lipset and Schneider, 1987). The final section of this chapter examines the evidence and debate on the performance of public organizations relative to the performance of the private sector, leading to the conclusion that in spite of the assumption to the contrary, many public organizations and managers perform very well.

Chapter Two described how the literature on organizations and management increasingly emphasizes the complexity and turbulence confronting organizations, with more and more discussion of paradoxes, conflicting values, and even the chaos facing all organizations (see, for example, Daft, 2013; Kiel, 1994; Peters, 1987; Quinn, 1988). For public organizations, the pressures include public and political hostility, funding reductions, and other challenges that many officials and experts depict as crises affecting all levels of government (Gore, 1993; Kettl, 2009; Light, 2008; National Commission on the Public Service, 1989, 2003; Partnership for Public Service, 2002; Thompson, 1993; U.S. General Accounting Office, 2002a; U.S. Office of Management and Budget, 2002; U.S. Senate, Committee on Governmental Affairs, 2001).

Somewhat paradoxically, in view of all the references to crisis and pressure, a growing literature has concentrated on successful organizations. Peters and Waterman’s In Search of Excellence (1982), which described many excellent corporations, became one of the best-selling popular books about management in history. It appears to have been the starting point for a profusion of similar books about successful corporate management that have been pouring out ever since (see, for example, Collins, 2001; Collins and Porras, 1997; Lawler and Worley, 2006).

Similarly, pressures on the public sector have prompted many authors and officials to defend the value and the record of government (Esman, 2000; Glazer and Rothenberg, 2001; Light, 2002b; Neiman, 2000) and public organizations (Milward and Rainey, 1983; Rainey and Steinbauer, 1999). In the leading book mounting the case in favor of government organizations, Goodsell (2004) pointed to substantial evidence that public organizations and employees frequently perform well and defy many of the negative stereotypes that echo in the media, popular opinion, and political and academic discourse. As described in previous chapters and later in this one, so many other writers have described effective public managers and organizations that books and articles on this topic represent a genre in the literature on administration.1 The debate over whether public organizations perform well, or as well as private firms, has many complexities. Previous chapters have discussed the many constraints on public organizations that can hamper their performance—complex sets of goals and difficulties in measuring performance, political interventions and turnover, externally imposed rules, inadequate resources and funding, policies and programs that are poorly designed by policymakers in the executive and legislative branches, and many others. It is fairly common for research to find that when public services are directly compared to privately delivered forms of the same service, the private sector displays more efficiency (Savas, 2000)—but not always (Donahue, 1990; Hodge, 2000; Sclar, 2000). In fact, Downs and Larkey (1986) described one national study that found that federal agencies showed higher rates of increase on productivity measures during the late 1960s than did a large sample of private firms. Individual agencies provide further examples. Studies have found that the U.S. Postal Service, the target of criticism and the brunt of jokes for decades, shows a much higher level of productivity per worker than any other postal service in the world, coupled with lower first-class mail rates than all but two other nations—Belgium and Switzerland—in spite of contending with greater geographic distances and other complexities. In addition, as Chapters Ten and Thirteen illustrate, there are many examples of innovative behaviors in public organizations and of studies that have found receptivity to change among public employees and no difference between the public and private sectors in general innovativeness.

In fact, the population of private and nonprofit organizations displays abundant weaknesses in many ways. Scholarly analyses and media reports regularly detail failures and bankruptcies, massive expensive blunders, and patterns of fraud and abuse in many of these organizations, sometimes in the most prestigious and reputable of them. In the first several years of the twenty-first century, such reports reached a crescendo. At times the litany of problems is so long that one wonders whether these sectors can serve as useful guiding models for the public sector. Conversely, just as with the public sector, the list of successes by business and nonprofit organizations is long and impressive, often involving accomplishments that would have seemed miraculous to people living even a few decades ago.

The point, then, is not to belabor invidious questions about whether one sector is better than another, but to underscore the challenge of pursuing excellence in all managerial settings. Many public and private organizations perform very well. What can we learn from studies of them?

Profiles of Corporate Excellence

To examine some profiles of corporate excellence, we might delve back into the recent history of the management literature. Peters and Waterman’s In Search of Excellence (1982), now somewhat dated, apparently became so popular because it forged beyond complicated debates about organizational effectiveness and put forth stimulating observations about management in excellent firms (although the authors’ conclusions actually echo much of the earlier literature on human relations in organizations and organizational responses to complexity). Peters and Waterman described these firms as placing a heavy emphasis on “productivity through people” (p. 14). They did not merely mouth that value, the authors said; they “live their commitment to people” (p. 16), and they “achieve extraordinary results with ordinary people” (p. xxv). They definitely try to attract and reward excellent performers, but they also emphasize both autonomy and teamwork.

The firms studied by Peters and Waterman devoted careful attention to managing their organizational culture. They developed coherent philosophies about product quality, business integrity, and fair treatment of employees and customers. Along with the stories and slogans that flourished in these companies, these philosophies emphasized the shared values that guided major decisions and motivated and guided performance. The firms nurtured the philosophies through heavy investments in training and socialization. “Without exception,” the authors noted, “the dominance and coherence of culture proved to be an essential quality of the excellent companies” (p. 75). The firms behaved as if they accepted the principle that “soft is hard”; that is, that the intangible issues of culture, values, human relations—matters that many managers regard as fuzzy and unmanageable—can and must be skillfully managed.

The successful firms sought coherence in their approach to management, with the shared values of the culture guiding the relationships between staff characteristics, skills, strategies, structure, and management systems. In so doing, they accepted ambiguity and paradox as part of the challenge. Organizing involves paradoxes, wherein one tries to do conflicting things at the same time, under conditions that often provide little clarity. The paradoxical aspects are evident in some of these companies’ approaches to management, which Peters and Waterman describe in these terms:

- A bias for action. These companies tended toward an approach that one executive described as “ready, fire, aim.” They avoided analyzing decisions to death and took action aggressively.

- Staying close to the customer. Deeply concerned about the quality of their products and services, people in these companies sought to stay in close touch with their customers and to be aware of their reactions.

- Valuing autonomy and entrepreneurship. Many of these companies provided autonomy in work and encouraged people to engage in entrepreneurial behaviors. They often tolerated the failure of well-intended, aggressive initiatives.

- Enhancing productivity through people. As noted earlier, the companies emphasized motivating and stimulating their people through respect, participation, and encouragement. They often used imagery, language, symbols, events, and ceremonies to do this.

- A hands-on, value-driven approach. The people in these firms devoted much attention to clarifying and stating the primary beliefs and values that guided the organization, to clarifying what the company “stands for.”

- Sticking to the knitting. The companies stayed focused on the things they did well and avoided ill-advised forays into activities that diluted their efforts and goals.

- A simple form and lean staff. The companies often had relatively simple structures and small central staffs. Some massive corporations achieved this by decentralizing into fairly autonomous business units, each like a smaller company in itself.

- Simultaneous loose and tight properties. The companies balanced the need for direction and control with the need for flexibility and initiative. They might have had “tight” general guidelines and commitments to certain values, but they allowed considerable flexibility within those general values and guidelines. The approach that the Social Security Administration took when it adopted its modular work units (described in Chapter Thirteen) appears to fit this pattern. The change followed a clear, general concept—modularization—with firm commitment from the top, yet units could adopt the concept experimentally and flexibly. They could make reasonable adaptations, but not radically depart from the basic idea. This example suggests the ways in which many of these approaches mesh together. A relatively clear idea for a change, coupled with relatively clear and appealing values expressed as part of that idea, provides both a source of motivation and direction and a reasonable framework that higher levels can firmly insist on, without being rigid or dictatorial.

At about the same time as Peters and Waterman’s book appeared, Americans became increasingly interested in the success of Japanese firms, which had been competing so effectively against American companies in many key industries. Observations of these firms revealed similarities to the particularly successful American companies. In one prominent book on the topic, Ouchi (1981) observed that many Japanese firms offered lifetime employment and avoided layoffs in hard times. They expressed a holistic concern for their employees. They moved slowly in evaluating and promoting personnel. They used more implicit control mechanisms, such as social influences on employees. They practiced collective decision making and collective responsibility, and developed relatively nonspecialized career paths.

The Japanese companies sought to develop trust on the part of their employees so they would have the confidence to contribute to the organization in many ways. They emphasized work groups as the basis for collective decisions and responsibilities. The companies emphasized the development of philosophies or styles that guide organizational objectives, operating procedures, and major decisions, such as new product lines. They supported these philosophies through extensive training programs. Ouchi noted that some successful American corporations, such as IBM, Procter & Gamble, Hewlett Packard, and Eastman Kodak (which were included in Peters and Waterman’s study), had orientations similar to some of these aspects of Japanese management.

The appearance of books such as these, especially the Peters and Waterman book and several sequels and television programs on the same theme, produced a movement within management circles in the United States. Numerous similar books appeared, and many corporations took steps to emulate the purported patterns of excellence. More and more annual reports proclaimed a company philosophy, typically including sonorous expressions of devotion to employees, customers, and high-quality products. The annual report of one high-tech firm described the company as a “closely knit family” of forty thousand.

Predictably, controversy followed this material on corporate excellence and Japanese management. The generalized observations about the characteristics of successful firms leave some questions about just how valid they are and how closely they apply to any particular organization. It is not always clear how one carries out some of the prescriptions these books offer—especially how one weaves them all together. Also, Peters and Waterman themselves noted that some managers told them that culture is only one of many important aspects of their organization. Other features, such as sound technical and production systems, can figure just as crucially. Some of the supposedly excellent companies that Peters and Waterman studied encountered difficulties later. A strong downsizing trend among corporations in the United States soon began to erode any claims that successful corporations placed great value on their people. Nevertheless, there are important reasons to look back at Peters and Waterman and Ouchi as representative and leading examples of the wave of books on corporate excellence. For one, these books make valuable and fascinating points, including the importance of people and organizational culture, the inevitability of paradox and ambiguity and the necessity to manage them, and the feasibility of managing complex organizations successfully. Many of these points and themes still echo in the management literature and in the professed philosophies of numerous organizations, and they echo in the accounts of effective public management reviewed in earlier chapters and in this one. However, a large number of the studies of effective public management have followed a similar pattern of providing general case descriptions of purportedly effective, innovative, and high-performance public managers and organizations. This raises many of the same issues about how clear, valid, and widely practiced are the values and practices that the authors conclude are responsible for the organizations’ success.

Research on Effective Public Organizations

Strikingly, the corporate excellence literature turned on their heads some frequent observations about the problems of public organizations. The Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 institutionalized the belief that weak links between pay, firing, and performance cause public organizations to perform poorly, and this belief has continued to play a strong role in discussions of governmental reforms (Rainey and Kellough, 2000). The writers on corporate excellence said that although the best profit-oriented firms tried very hard to recognize and reward excellent performers, they also emphasized a culture of communication, shared values, and mutual loyalty and support between the organization and its employees, as well as decentralization, flexibility, and adaptiveness. Although governmental reforms have sometimes claimed to pursue such conditions, and sometimes have involved efforts to do so, the reforms tend to mix such themes with the message that dysfunctional government agencies and many poor performers in them need to be fixed, through such measures as pay-for-performance schemes and streamlined procedures for firing and discipline (Rainey and Kellough, 2000; Walters, 2002). This raises the question of how government can actually pursue enlightened reforms in a context of constant criticism and skepticism—a question all the more important as government confronts the apparent human capital crisis described shortly. At the same time, it shows the importance of paying attention to the reports of effective government organizations, because in many of these reports one finds applications of some of the important values and philosophies that successful private corporations reportedly apply.

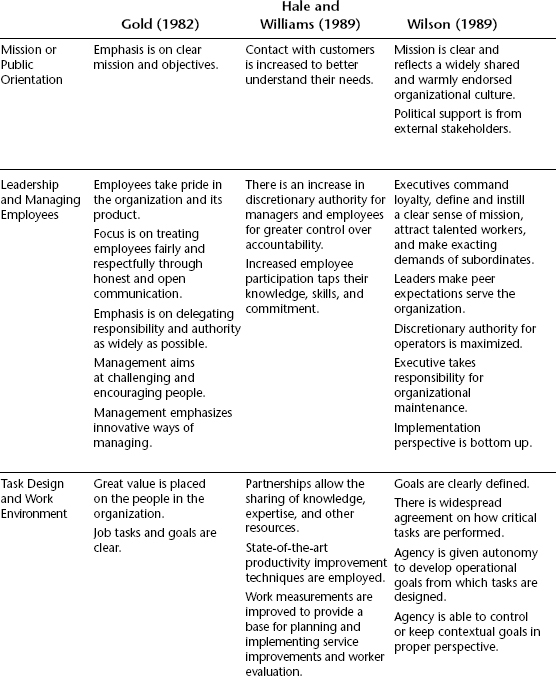

In one of the earliest examples of research on government organizations, resembling the approach of Peters and Waterman, Gold (1982) studied ten successful organizations—five public and five private. He chose healthy organizations with well-respected products or services that appeared to be good places to work; the public organizations were the U.S. Forest Service; the U.S. Customs Service; the U.S. Passport Office; and the city governments of Sunnyvale, California, and Charlotte, North Carolina. The private organizations were a regional theater organization; the Dana Corporation (an automobile parts manufacturer); Hewlett Packard; L. L. Bean; and Time, Inc. He found that the ten organizations had certain common characteristics:

- They emphasized clear missions and objectives that are widely communicated and understood throughout the organization.

- The people in the organization saw it as special because of its products or services, and they took pride in this.

- Management placed great value on the people in the organization, on treating them fairly and respectfully, and on open, honest, informal communication with them.

- The managers did not see their organization as particularly innovative, but they emphasized innovative ways of managing people.

- Management emphasized delegation of responsibility and authority as widely and as far down in the organization as possible. They involved as many people as possible in decision making and other activities.

- Job tasks and goals were clear, and employees received much feedback. Good performance earned recognition and rewards.

- The handling of jobs, participation, and the personnel function was aimed at challenging people and encouraging their enthusiasm and development.

Gold did find some distinctions between the public and private organizations, however. The public organizations did not articulate their mission as clearly and consistently as the private ones did. Apparently the private organizations’ focus on profit as an element of their objectives helped in this regard. The managers in the public organizations, however, talked about excellence in the professionalism of the staff and about smoothly run operations and processes. The public organizations also had a harder time promoting from within—an approach that the private firms emphasized as a way of building experience, knowledge, and commitment among their employees.

As indicated by the many references cited earlier in this chapter and in previous ones, these types of studies have continued to appear. At one point, Hale (1996) summarized the conclusions of some of the most recent studies of high-performance public agencies. She concluded that in high-performance organizations, leaders define their key role as providing conditions that support employee productivity and that support employees in providing the organizations’ customers with what they want and need from the organization. These organizations, and their leaders, typically hold the following values:

- Learning. They support learning, risk taking, training, communication, and work measurement.

- A focused mission. They emphasize clarifying their mission and communicating it to the members of the organization, its customers, and other stakeholders.

- A nurturing community. They provide a supportive culture, with a focus on teamwork, participation, flexible authority, and effective reward and recognition processes.

- Enabling leadership. They facilitate learning, communication, flexibility, sharing, and the development of a vision and commitment to it.

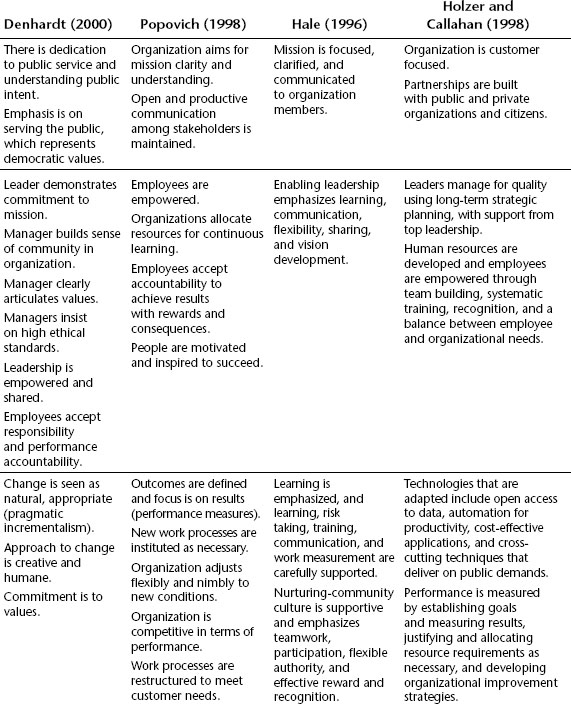

Later, Rainey and Steinbauer (1999) sought to further develop the sort of summary that Hale undertook. They bluntly asserted that public organizations can be very successful and effective, by reasonable standards, and as effective as business firms. They pointed to various examples of effective performance of government agencies, such as the low administrative expenses of the SSA, which represent only about 0.8 percent of the total benefits that the SSA disburses (Eisner, 1998). They sought to pull together the studies of high-performance and excellent government organizations and looked for common patterns and generalizations, as illustrated in Table 14.1. As that table indicates, and as summaries of these types of studies here and in Chapter Thirteen also show, these studies vary widely in their methods, in the concepts and terms they use, in the degree to which they provide clear evidence in support of their conclusions, and in other ways. This makes it a difficult task to describe and summarize them, and it takes a lot of time and space to do so. Exhibit 14.1, however, provides a set of propositions that Rainey and Steinbauer offered as a result of the review.

Table 14.1. CHARACTERISTICS OF HIGH-PERFORMANCE GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATIONS

Source: Portions of this table are adapted from Rainey and Steinbauer, 1999, p. 359; and from Hale, 1996, p. 139.

Obviously one can criticize this set of propositions and debate its adequacy on many grounds, such as the clarity of the concepts and the adequacy of the evidence supporting them. It does make the point, however, that numerous researchers and authors are advancing evidence of successful, effective organizations and management in public organizations. This in turn suggests that many public organizations are managed as well as or better than private ones, and that many public managers perform very effectively. These propositions raise the challenge of continuing to develop our knowledge of how public organizations achieve these effective performances and change for the better.

Trends and Developments in the Pursuit of Effective Public Management

Besides the research on effective public organizations, a number of trends and developments related to the pursuit of effective public management are worthy of attention. A vast array of such activities and initiatives goes on constantly, and previous chapters have covered many of them, such as the Government Performance Project, applications of the Balanced Scorecard in the public sector, and the Government Performance and Results Act and the efforts at strategic planning that it required (all covered in Chapter Six). It is difficult to decide which additional developments to cover, but everyone interested in public management should be aware of the developments covered here. They serve to illustrate certain points about the context and dynamics of the theory and practice of management in general and of public management.

Total Quality Management

In the past two decades, organizations throughout the public and private sectors have undertaken Total Quality Management (TQM) programs. The widespread implementation of these programs makes it important for public managers and students of public management to be aware of TQM. As we will see, TQM also raises challenging alternatives for management, and it has clearly influenced the objectives of current government reform efforts described later in this chapter (for example, focusing on the customer, the use of teams, and continuous improvement) and the literature on public management (for example, Beam, 2001). It also provides an interesting and significant example of the dissemination of ideas and techniques in public and private management (Berman and West, 1995).

The term Total Quality Management refers more to a general movement or philosophy of management than to a specific set of management procedures. Different authors take different approaches to TQM. W. Edwards Deming, one of the founders of this movement, who developed many of the original ideas behind it, did not refer to his approach as Total Quality Management. In fact, he disapproved of this label. Yet a review of some of Deming’s seminal ideas provides a useful introduction to TQM (Dean and Evans, 1994; Deming, 1986; Juran, 1992).

Deming was an industrial statistician. Writing in the 1950s, he advocated using statistical measures of the quality of a product during all the phases of its production. He called for this approach to replace the quality-control procedures often used in industry, which assessed the product only at the end of the production process. Deming included this commitment to statistical quality control in his general philosophy of management. He put together fourteen tenets of his approach. These tenets, frequently quoted in the TQM literature, include the following:

- Attentive

- Demanding

- Supportive

- Delegative

- Favorable public opinion and general public support

- Multiple, influential, mobilizable constituent and client groups

- Effective relations with partners and suppliers

- Difficult but feasible

- Reasonably clear and understandable

- Worthy and legitimate

- Interesting and exciting

- Important and influential

- Distinctive

- Stability of leadership

- Multiplicity of leadership—a cadre of leaders, teams of leaders at multiple levels

- Leadership commitment to mission

- Effective goal-setting in relation to task and mission accomplishment

- Effective coping with political and administrative constraints

- Intrinsically motivating tasks (interest, growth, responsibility, service, and mission accomplishment)

- Extrinsic rewards for task accomplishment (pay, benefits, promotions, working conditions)

- Effective recruitment, selection, placement, training, and development

- Values and preferences among recruits and members that support task and mission motivation

- High levels of special knowledge and skills related to task and mission accomplishment

- Commitment to task and mission accomplishment

- High levels of public service professionalism

- High levels of public service motivation among members

- High levels of mission motivation among members

- High levels of task motivation among members

- Publish a statement of company aims and purposes for all employees to see, and demonstrate commitment to the statement on the part of management.

- Have everyone in the company learn and adopt the new philosophy.

- Constantly improve the production system.

- Institute training, teach leadership skills, and encourage self-improvement.

- Drive out fear and create trust and a climate of innovation.

- Use teams to pursue optimal achievement of company goals.

- Eliminate numerical production quotas and management by objectives, and concentrate on improving processes and on methods of improvement.

- Remove barriers to pride of workmanship.

Although some of these tenets sound simple, many have profound implications for an organization’s basic approach to organizing and managing. For example, these principles led Deming to oppose individualized performance appraisals because they damage teamwork, fail to focus on serving the customer, and usually emphasize short-term results. Compare his orientation to the themes in civil service reforms and government pay reforms described in Chapter Nine (for example, pay-for-performance plans based on individual performance appraisals, and the streamlining of procedures for firing and disciplining employees). In contrast, Deming argued that to make the commitment to improving quality work, people have to feel free to contribute their ideas about problems and improvements. Hence, the leaders of the organization must “drive out fear.”

Deming argued that his approach to management represented a general philosophy that must receive total commitment from the organization. Measures of quality should be used at all phases of production and should be the basis for continuous efforts to improve quality. The organization should strive to improve relative to its own previous quality measures as well as to those of comparable organizations. The quality measures should be based on the preferences and point of view of the organization’s customers.

When Deming first began to advance his ideas, they received little attention from managers in the United States. The Japanese, however, embraced his ideas enthusiastically, and the Deming Award became a very prestigious award in Japan for excellence in management. As Japanese firms joined the list of the most successful firms in the world and began outcompeting U.S. firms in many markets, managers in the United States decided that they needed to pay some attention to what this fellow Deming had to say. For example, Deming was instrumental in the Ford Motor Company’s adoption of a corporate strategy and philosophy based on a commitment to quality (Dean and Evans, 1994). The general acceptance and adoption of these programs became so widespread that in 1987 Congress passed legislation establishing the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award Program (named for a former U.S. secretary of commerce), which annually recognizes organizations with excellent quality management programs and achievements.

Well-developed TQM programs tend to involve such conditions and principles as the following (Cohen and Brand, 1993; Dean and Evans, 1994):

- An emphasis on defining quality in terms of customer needs and responses

- Working with suppliers to improve their relationship to the quality of the organization’s production processes and products

- Measurement and assessment of quality at all phases of production, with commitment to continuous improvement in quality; benchmarking quality measures against similar measures for similar organizations as a way of assessing improvement and general level of performance

- Teamwork, trust, and communication in improving quality; use of decision-making and quality-improvement teams involving participants from many areas and levels of the organization that are involved in the production process

- Well-developed training programs to support teamwork and quality assessment and improvement

- A broad organizational commitment to the process, from the top-executive ranks on down, that encompasses strategy, cultural development, communication, and other major aspects of the organization

In well-developed programs, top executives demonstrate commitment and leadership. Symbols, language, communication, and training are coordinated around the quality program. In some of the companies, for example, every employee receives sixty days of quality training within two weeks of joining the organization, and everyone, including the CEO, takes the training. The training often involves coverage of a fairly standard set of analytical procedures, including such techniques as cause-and-effect (“fishbone”) diagrams; flowcharts; and procedures for counting and tabulating data related to production quality, and for analyzing causes and interpretations.

Although the TQM movement originally focused on industry, it swept through government as well, with applications in many different types of agencies and at all levels of government (Council of State Governments, 1994). Consistent with the theme of this book, the basic principles of TQM emphasize that successful total quality efforts depend heavily on commitment and strategic implementation (Cohen and Brand, 1993). The principles of TQM are often general, stressing leadership, culture, incentives and motivation, groups and teams, and many of the other topics covered in previous chapters. Failed TQM efforts often display the opposite of these qualities—insufficient leadership, weak culture, weak management of the change process, and poor provisions for motivation and teamwork.

TQM has its detractors, who criticize it as one more management fad that will soon be supplanted by another. Significantly, early in the twenty-first century, fewer and fewer organizations appeared to be implementing TQM programs, and many organizations appeared to be abandoning them, although many similar approaches—such as high-performance work systems and high-performance organizations—continued in various ways (Appelbaum, Bailey, Berg, and Kalleberg, 2000; Lawler, Mohrman, and Benson, 2001). However, TQM obviously has very challenging and interesting features, especially for government. It proposes a management philosophy quite opposed to the one that has prevailed in many government reforms in recent years (Peters and Savoie, 1994; Rainey and Kellough, 2000). Also, its history illustrates the need for comprehensive, strategic approaches to many innovations in management—approaches that apply many of the ideas covered in previous chapters.

The Reinventing Government Movement

Osborne and Gaebler’s book Reinventing Government (1992) became a best-seller during the early 1990s and influenced many government reforms in the years since its publication (Brudney, Hebert, and Wright, 1999; Brudney and Wright, 2002; Gore, 1993; Hennessey, 1998; Kearney, Feldman, and Scavo, 2000). Its approach and its success resemble those of Peters and Waterman’s In Search of Excellence, and one can appropriately characterize Reinventing Government as the public sector equivalent of that book. Like the other studies of excellence in public management described earlier, it provides provocative and challenging ideas about approaches to public management and the delivery of government services. Interestingly, however, its perspective on the state of performance in the public sector was mixed. The authors introduced the book with the claim that in many ways government is failing and breaking down. Yet they also argued that government plays an essential role in society and has to define and carry out that role effectively—hence the need for reinvention. In particular, the authors attacked the old-fashioned, centralized, bureaucratic model that dominated many government agencies and programs. They called for more entrepreneurial activities to supplant that approach.

Significantly, however, to support their call for a more entrepreneurial approach in government, they cited many government practices they had observed around the country that were already quite effective, such as decentralizing, encouraging privatization, encouraging control of programs at the community level, increasing attention to the “customers” of government programs, finding ways for government to make money on its operations (“enterprising government”), and increasing competition among government programs and between government and the private sector. Exhibit 14.2 summarizes their strategies for more entrepreneurial government. They illustrated the use of these strategies through numerous examples from government programs.

Their proposals had a rapid, major impact, including the establishment of the Clinton administration’s National Performance Review, described later. REGO (reinventing government) became a widely used term in the federal government and in other government circles. The REGO trend heavily influenced a broad array of developments, including the reinvention of the civil service system of the state of Florida and an entrepreneurial effort at getting a hotel built in downtown Visalia, California. These two examples are quite significant, because according to some observers they were unsuccessful. Wechsler (1994) concluded that the civil service reform efforts in Florida had little important effect. Gurwitt (1994) reported that the Visalia episode had bad results. There, government officials wanted a hotel built downtown to support economic development efforts. Pursuing entrepreneurial strategies, they tried to avoid spending government funds to subsidize the development of the hotel. They bought land and worked out an arrangement with a developer to lease the land from the city and build a hotel on it. This way, the city would make money on the arrangement through the lease payments. Unfortunately, the developer folded, and rather than give up on the project and take a loss, the city assumed more than $20 million of the developer’s debts.

Several studies have sought to assess the implementation of REGO reforms at different levels of government. Brudney, Hebert, and Wright (1999) found limited implementation in state governments of reforms representing REGO ideas, except for fairly widespread efforts at strategic planning, but a later survey showed some increase in the implementation of REGO reforms (Brudney and Wright, 2002). Kearney, Feldman, and Scavo (2000) surveyed 912 city managers and found high levels of agreement with principles and ideas similar to those proposed by Osborne and Gaebler. The city managers, however, were less likely to have taken action to implement the principles and ideas than they were to express agreement with them. Interestingly, studies of reinvention initiatives have tended to find that leadership support played a strong role in their implementation (see, for example, Brudney and Wright, 2002; Hennessey, 1998).

As these examples and studies show, the REGO ideas have been influential, but also controversial. For example, some critics have raised concerns about thinking of citizens as customers of public organizations. In addition, many of the REGO proposals, such as efforts to privatize public services, have been going on for centuries, and Frederickson (1996), a leading scholar in public administration, has likened them to “old wine in new bottles.” Yet, like many new approaches, the proposals can also be regarded as stimulating and challenging, and the research and examples just described underscore a main theme of this book: challenging new ideas require effective implementation, and in government, implementation requires effective public management.

The National Performance Review

The REGO movement influenced the Clinton administration’s National Performance Review (NPR). As with the other developments described in this chapter, the NPR deserves attention as a major reform effort in public management. Some experts regarded the NPR as unprecedented in terms of the activity it generated and the attention it received (Kettl, 1993). The NPR involved a review of federal operations by a staff in Washington under the leadership of Vice President Gore. Among other activities, Gore conducted meetings with employees in federal agencies, ostensibly to gather ideas about problems and solutions, but also with the obvious intent of making a symbolic statement.

In many ways, the NPR’s tenor was similar to that of the reinventing government movement (see Exhibit 14.3). The first report (Gore, 1993) argued that the federal government needed a drastic overhaul to improve its operations—a reinvention similar to that in many corporations that had reformed themselves in the face of international competition in the 1980s. Yet the report—and Gore, in his public statements and actions (such as his meetings with agency employees)—took the position that federal employees were not to blame for the problems in government. The structures and systems were the problems, the report said, and it emphasized the importance of listening to federal employees’ ideas and observations. The report announced numerous initiatives to reform the structure and operations of the federal government, as well as many change efforts within federal agencies. Exhibit 14.3 summarizes some of the major priorities and initiatives announced in the first report of the NPR. As the exhibit suggests, the NPR emphasized the need to reform many of the constraints on federal agencies discussed in this book. The reforms would decentralize and relax personnel and procurement regulations, for example.

- Streamline the budget-making process. Use biennial budgeting; relax OMB categories and ceilings; allow agencies to roll over 50 percent of funds not spent.

- Decentralize personnel policy. Eliminate the Federal Personnel Manual; allow departments to conduct their own recruiting, examining, evaluation, and reward systems; simplify the classification system; reduce the time to terminate employees and managers for cause and to deal with poor performers.

- Streamline procurement. Simplify procurement regulations; decentralize GSA authority for buying information technology; allow agencies to buy where they want; rely on the commercial marketplace.

- Reorient the inspectors general. Reorient the inspectors general from strict compliance auditing to evaluating management control systems.

- Eliminate regulatory overkill. Eliminate 50 percent of internal agency regulations; improve interagency coordination of regulations; allow agencies to obtain waivers from regulations.

- Empower state and local governments. Establish an enterprise board for new initiatives in community empowerment; limit the use of unfunded mandates; consolidate grant programs into more flexible categories; allow agency heads to grant states and localities selective waivers from regulations and mandates; give control of public housing to local housing authorities with good records.

- Give customers “voice” and “choice.”

- Make service organizations compete.

- Create market dynamics and use market mechanisms.

- Decentralize decision making.

- Hold federal employees accountable for results.

- Give federal workers the tools they need.

- Enhance the quality of work life.

- Eliminate what we don’t need.

- Collect more.

- Invest in productivity and reengineer to cut costs.

Many of the NPR reforms also reflect the management trends described in this book—including the prescriptions of Peters and Waterman, TQM, REGO, and others—with an emphasis on serving the customer, decentralization, empowerment, and relaxed controls. The report thus provides an interesting example of the infusion into government reform of trends and ideas in business management.

Predictably, the NPR was controversial in public administration circles, in terms of whether it was well conceived and whether it would have lasting and beneficial effects. Without question, however, it caused a lot of activity in federal agencies. Among other steps, the NPR announced and carried out a major reduction of the federal workforce, mentioned in several previous chapters (U.S. Office of Management and Budget, 2002). This gave rise to questions about whether such cuts were really the result of an ulterior motive behind the glowing discourse about reforms, and whether the NPR was simply part of the recent trend of presidents attacking the bureaucracy for political effect (Arnold, 1995). In addition, many of the NPR initiatives were implemented by executive order, including one instructing federal agencies to reduce their internal regulations by 50 percent and one eliminating the elaborate federal personnel manual. Such measures seemed to have little impact.

Subsequent NPR reports announced additional reforms. An executive order directed federal agencies to publish customer service standards, and a great many did (Clinton and Gore, 1995). Follow-up reports announced indications of progress, such as reductions in regulations, cost savings of $58 billion, and a variety of steps in different agencies to improve operations and services (Gore, n.d.). One of the efforts under the NPR involved a presidential directive ordering federal agencies to set up so-called reinvention laboratories to work on improving their procedures. Some of these reinvention labs reported successes in finding improved and innovative ways of carrying out their agency’s business, although they also encountered many obstacles to change (Sanders and Thompson, 1996).

Thompson (2000) assessed the impact of the NPR by examining results of surveys of employees and other sources of evidence, and through an in-depth case study of its implementation in the SSA. He concluded that the NPR did effect impacts in the major reduction in federal jobs, in reducing administrative costs in the federal government, in reforming the federal procurement system, in empowering front-line managers and employees, and in establishing labor-management partnerships. He found little evidence of impacts in the reform of the civil service system in order to decentralize it, in enhancing service delivery to the public, and in reengineering and streamlining work processes in agencies. He also found very limited impacts within the SSA.

It was easily predictable, moreover, that the success of the NPR would depend on the political fortunes of the administration that sponsored it. As if to provide a perfect example of one of the frequently noted obstacles to change and reform in government, Vice President Gore lost the presidential election to George W. Bush, and soon the activities associated with the NPR were terminated. A search for its Web site now takes you to a “cybercemetery” at North Texas State University, where its documents are archived.

Ultimately, the NPR illustrated many of the obstacles to reform in government. At the same time, however, it represented a historic initiative in the pursuit of improved public management. Whether or not it was the right thing to do, a massive reduction in federal employees represents a major impact. Also, reforms of the procurement system and the reductions in federal administrative expenses represent important accomplishments. The NPR, in addition, documented many examples of effective public management. It received relatively strong support from top executives (the president and vice president), it made an effort to involve organizational members (the federal employees) in change and to enlist their support, and it advanced measures for decentralized diagnosis and incremental improvement of performance problems (the reinvention labs). Significantly, it clearly exerted far more influence on the federal government and its agencies than did Reagan-era reform efforts such as the Grace Commission.

The President’s Management Agenda

The second President Bush was the first president to have a management degree, and early in his administration he indicated an interest in management by issuing the President’s Management Agenda. The agenda announced five primary government-wide initiatives: Strategic Management of Human Capital, Competitive Sourcing (employing competition to decide whether federal employees or private contractors should provide federal services), Improved Financial Performance, Expanded Electronic Government, and Budget and Performance Integration. The U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) then issued agency scorecards to twenty-five major federal agencies that were based on discussions with experts in government and universities (U.S. Office of Management and Budget, 2002). The scorecards used a “traffic light” grading system for each of the five government-wide initiatives. A green light meant success, yellow meant mixed results, and red meant unsatisfactory. In the early phases of this process, of the 130 traffic lights awarded to the twenty-six agencies on the five initiatives, only nineteen were yellow, one was green, and the rest were red. OMB then began to publish an additional listing of the agencies, awarding green, yellow, and red lights on the basis of the progress they were making in the five areas. The five agenda priorities reflected important management issues in the federal government and at other levels that had advocates other than the Bush administration. In some ways they reflected priorities that the NPR and other reform efforts have also emphasized. How much reform and progress the agenda and the traffic lights accomplished will also be an agenda item for researchers and observers in public management in coming years.

Performance Measurement and the PART

As many of the developments described here indicate, during the last decades of the twentieth century and the first decade of the new century, experts and public officials emphasized improving government’s performance in various ways. Governments at all levels in the United States and other nations adopted systems and procedures for measuring governmental performance and for “performance management” procedures to try to use the measures to improve performance (Moynihan, 2008). Among many examples of such developments, the New York City Mayor’s Office of Operations (2009) publishes on its Web site a Citywide Performance (CPR) “tool.” This performance reporting system provides information on hundreds of performance indicators for all the agencies of the city government. The Web site allows a citizen to choose a city agency and then review the agency performance report, which reports on the agency’s performance against numerous performance indicators for that agency.

At the federal level in the United States, the George W. Bush administration’s management improvement efforts, described earlier, included development of the Program Assessment Rating Tool (PART) (Gilmour, 2006). The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in the Executive Office of the President developed the PART and conducted assessments of over eight hundred federal programs within federal departments and agencies. With oversight by OMB examiners, representatives of each program responded to a series of questions about four categories of the program’s activities and accomplishments, in program purpose and design, strategic planning, program management, and program results (performance on strategic goals). On the basis of the program’s responses, OMB examiners assigned a score from zero to one hundred in each of these categories. Then the examiners assigned an overall performance score that combined the four categories of indicators, with different weightings on the categories. The category for program results had the highest weighting. OMB then assigned the program a grade of effective, moderately effective, ineffective, or “results not demonstrated.”

OMB officials intended that the PART results would be used in decisions about the programs’ budgets and would thus contribute to the goal of integrating budget and performance of the President’s Management Agenda described earlier. The PART was intended to support assigning program budgets on the basis of results. Gilmour and Lewis (2006a) analyzed PART scores and program budget allocations. They found relationships between the two, but not the sorts of relations that supported the original intent of the PART. Gilmour and Lewis reported that the PART scores showed a relation to budget decisions for small and middle-sized agencies, but not for large agencies. This could indicate that larger programs are more entrenched and have more political support for defending their budgets. They also found that the “results” component of PART scores had a smaller impact on budget decisions than the “program purpose” component, which included questions about the clarity of the program’s goals. This finding does not indicate a strong relationship between actual program results and budget decisions.

The PART sparked controversy. OMB officials claimed that the PART procedures were very open. In developing the procedures, the OMB consulted professional associations and other agencies, such as the Government Accountability Office. The results were available on the OMB Web site. However, critics, such as Democrats in Congress, complained that the control of the process by the OMB under a Republican president could bias the assessments against programs that Democrats tend to favor. Other concerns focused on the difficulty of agreeing on acceptable and fair performance measures. Among other problems, sometimes the results for one program depend on the performance of another program. As discussed in Chapter Six, stating appropriate goals and measuring goal achievement raises challenges for organizations of all types, and especially public and nonprofit organizations.

The assessment of this assessment procedure became interesting in itself. Lewis (2008) found evidence that programs headed by career civil servants received higher PART scores than did programs headed by political appointees. This appears to weigh against the claims that the PART involved partisan bias against programs not favored by the Republicans. In addition, Gilmour and Lewis (2006b) used a variable that identified whether a program was located in a department or agency that tended to have more support from Republicans or from Democrats, and found that this did not make much difference. Both Lewis (2008) and Moynihan (2008) carefully consider the controversy over the PART. They come to balanced, but generally favorable conclusions about the value of the PART, at least as a carefully developed effort to provide performance information about a large and diverse set of federal programs for which comparable performance information had not been available. At the time of this writing, a search of the U.S. Office of Management and Budget Web site (www.omb.gov) indicates that PART has been placed in an archive, and the latest guidance for PART is dated 2008.

The Human Capital Movement

As mentioned earlier, other people besides members of the Bush administration have advocated reforms and improvements in the five areas that the President’s Management Agenda targeted. The issue of human capital has origins and imperatives similar to the human capital issues in many state governments (see, for example, Abramson and Gardner, 2002). This emphasis at the federal level responded in part to a purported crisis.

The term human capital attracted its share of ridicule. A Dilbert cartoon in 2002 portrayed Dogbert, one of the regular series characters, talking to Dilbert’s boss, who is always insensitive and inept, about human capital. Dogbert asked the boss if he preferred to refer to the employees as human capital or livestock. The boss said he preferred human capital because if they were to use the term livestock, the employees might demand hay. Human capital may sound somewhat dehumanizing because it conjures up the image of using human beings like machines or other capital stock. Proponents of this movement, however, intended totally opposite implications. They called for leaders to regard the human beings in their organizations as their most valuable asset. They argued that in the information age, when human knowledge and intellectual skills play such a crucial role in organizational success, leaders need to realize the value of investing in the human beings in their organizations and to help people develop their knowledge and skills. Moreover, organizations need to strategize, plan, and invest in making sure that this human-capital emphasis infuses the organization’s operations and its long-term development.

In addition to the OMB, David M. Walker, comptroller general of the United States from 1998 to March 2008, served as one of the main proponents of the human capital focus (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2002a, 2002b; Walker, 2001). Also, Senator Voinovich of Ohio advanced legislation on human capital issues that was included in the legislation authorizing the Department of Homeland Security, but Voinovich’s legislation applied the requirements to all federal agencies. The legislation required, for example, that each federal agency appoint a chief human capital officer to be responsible for strategic planning for human capital, aligning the strategic planning with the agency’s mission, and fostering a culture of performance and improvement.

The human capital movement was driven in part by concerns over a growing crisis in human capital in the federal government, a crisis that the situation in state and local governments tends to mirror. As one example of the problem, in 2010, 50 percent of the U.S. Senior Executive Service was projected to be eligible for retirement within five years (National Academy of Public Administration, 2010). As still another challenge, the rapid changes in information technology and other areas have forced changes in the sorts of skills and personnel needed in all types of organizations. These changes usually involve imperatives for bringing in more highly educated, trained, and skilled employees, for which organizations in the public, nonprofit, and private sectors compete aggressively.

In response to these developments, the participants in this movement concentrated on exhorting federal agencies to take human capital seriously, advising them on how to do it, and recommending or crafting legislation to set in place some of the structures and requirements to support it (such as chief human capital officers). The General Accounting Office (GAO, now called the Governmental Accountability Office), for example, issued frameworks, checklists, and a model to guide agency efforts (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2002a, 2002b). The GAO model provided a conceptual framework, guidelines, and pointers on how to achieve success in establishing four “human capital cornerstones”:

The long-term influence of the legislation, admonitions, traffic lights, frameworks, and guidelines coming from the human capital movement is difficult to evaluate conclusively. The imperatives motivating this activity, however, continue to represent major issues at all levels of government in the United States and other nations, and continue to receive emphasis by federal agencies and organizations concerned with public service (Partnership for Public Service, 2013b; U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2013).

Managing Major Initiatives and Priorities: Privatization and Contracting Out

These recent developments illustrate the point that effective management and organization in the public sector remains a crucial, dynamic challenge—a challenge that becomes especially apparent when we observe the implementation (or failed implementation) of new initiatives in government. As a concluding effort in this book, this section applies the framework shown in Figures 1.1 and 1.2, and the topics included in that framework, which have been elaborated on throughout the book, to the topic of organizing for and managing a recent trend in public management: the increasing emphasis on privatization of public services. As mentioned at the beginning of this book, effective management and leadership require sustained, careful, comprehensive approaches to the challenges of organizing and managing. The discussion that follows suggests how the conceptual framework presented at the outset, together with the concepts and ideas from the preceding chapters, can support the development of such an approach to this topic and, in doing so, suggest how it can be applied to other important topics, such as the management of volunteer programs (Brudney, 1990), of information technology initiatives, and of many other issues.

Although privatization has a long history in the United States and other nations, it has received greater emphasis lately as a strategy for dealing with tightened budgets in the public sector (and the consequent need for reducing costs and increasing efficiency) and for escaping alleged weakness of government through innovative and flexible ways of delivering public services. Yet proponents of privatization often overlook the point that privatization increases the imperative for effective public management rather than relaxing or easing it.

Managing Privatization

Government contracts with private providers are nothing new in the United States, but privatization has increased a great deal in the past several decades, with governments at all levels sharply increasing their contracts with the private sector (Chi, 1994; Cooper, 2003; Greene, 2002). In addition, privatization has increased in service areas where it has been rare in the past, such as the operation of prisons. As Chapters Five and Six mentioned, the expansion of privatization has raised questions about the “hollow state,” third-party government, and the changing nature of government and public management (Kettl, 1993, 2002; Milward, 1996; Moe, 1996; Smith and Lipsky, 1993). Privatization, then, is a widely and increasingly utilized mode of service delivery that imposes problems on public managers but also offers them strategic options (Cohen, 2001). Managing privatization effectively thus represents one aspect of excellence in public management.

During the past few decades, a wave of privatization initiatives has swept the globe, with nations on all continents trying to transfer government activities to private operators. Most nations have many more government-owned enterprises than the United States does, and in most of these countries privatization was concerned with how to sell or transfer such enterprises to private owners and operators. In the United States, by contrast, privatization primarily involves government contracts with private or nonprofit organizations to deliver public services and carry out public policies. Actually, privatization of public services can take many forms besides selling the operation or contracting it out, including the following:

- Granting a franchise to private operators

- Providing vouchers to service recipients to purchase services from private providers

- Using volunteers (for staff support or service delivery, for example)

- Providing subsidies and financial incentives to private operators, such as tax incentives, grants, and subsidization of startup costs

- Initiating self-help or coproduction programs, in which citizens perform services for their own benefit or share in providing them

- Selling off or shedding activities to private operators, or simply ceasing them so that private operators can take them over (Zahra, Ireland, Gutierrez, and Hitt, 2000)

For the most part, however, privatization in the United States involves contracts with nongovernmental organizations. As mentioned, contracts and similar arrangements such as grants and franchises have been part of government for a long time. In 1798, for example, Eli Whitney, the famous inventor, received a contract from the government to provide ten thousand muskets in two years; it took him ten years to finish the project (Dean and Evans, 1994, p. 5).

Privatization Pitfalls and Ironies

The example of Whitney’s eighteenth-century time overrun highlights one of the many pitfalls of privatization. In recent years, proponents of privatization, some of whom show an obvious ideological bias toward private business and against government activity, have promoted privatization as a bold new initiative. Yet the Whitney example and thousands of similar ones remind us that privatization is as old as the republic and that, although it has produced many benefits, its history has been fraught with scandals and problems. In addition, rather than offering a private sector alternative to government, privatization can lead to governmentalization of the private sector, in which government increasingly draws segments of the private sector into its sphere of activity (Moe, 1996). Private contractors and service providers can then become just one more interest group, lobbying for government policies favorable to themselves and their industry or service area (Smith and Lipsky, 1993). The greatest irony of privatization, however, is that it increases demands for excellence in public management rather than alleviating them. Proponents tout it as a cure for bad government, but it takes excellent government to make it work. The discussions of third-party government in earlier chapters point out that contracting out and other forms of privatization, grant programs, and operation of government services by nongovernmental organizations strain the lines of management and accountability. Public managers become increasingly responsible for programs and services over which they have less control. They can influence the outcomes of such programs and services only through the vehicles spelled out in their contracts with private service providers, rather than through direct administrative control. Major issues, such as the legal liability of government and public managers, can become more complex and uncertain (Cooper, 2003). As the history of privatization has shown, private service providers may perform poorly or even illegally. As Sclar (2000) points out, “you don’t always get what you pay for” (see also Kuttner, 1997). Armed only with relatively loose lines of control and accountability, government officials nevertheless share responsibility for such failures. Strong advocates of privatization continue to claim that it produces more efficient and effective delivery of public services (Savas, 2000). Conversely, Hodge (2000) reports a meta-analytic study of hundreds of studies of privatization in many different nations and concludes that privatization can lead to modestly lower costs; such gains, however, tend to concentrate in certain service areas, such as refuse collection and building maintenance, with no appreciable gains apparent in other service areas. In spite of such controversies over just how beneficial privatization can be, it persists as an option, not only because some ideologues simplemindedly promote it, but in part because it can offer a valuable alternative for government managers. It can produce savings and efficiencies, flexibility in management, and other strategic advantages. Thus, to avoid the problems and take advantages of the promise, successful privatization requires skillful public management.

What does successful management of privatization involve? We now have a well-developed literature on privatization and contracting out that considers their pros and cons and what needs to happen for such strategies to work well (Brown and Potoski, 2003; Chi, 1994; Cooper, 2003; Donahue, 1990; Fernandez, Malatesta, and Smith, 2013; Malatesta and Smith, 2011, 2013; Rehfuss, 1989; Romzek and Johnston, 2002; Savas, 2000; Sclar, 2000; Van Slyke, 2003; Warner and Hebdon, 2001). Exhibit 14.4 presents some of the conditions that should be in place for successful privatization and contracting out, according to the professional literature. As noted, proponents make very strong claims for privatization as a panacea for the alleged ills of government. They point to a fairly consistent set of research findings that indicate that private organizations often provide services at lower costs per unit of output compared to government agencies. Other authors, however, point to some problems with many of these studies and to the complication introduced by the fact that government organizations often have to pursue different goals and values from those of private organizations, even in the same service areas (for example, see the sections in Exhibit 14.4 on goals and values and on performance and effectiveness). In addition to not focusing on the many examples of problems with private sector contracts and how to avoid them, these studies, frequently conducted by economists, tend to overlook the issue of management.

A growing body of experience and research has increasingly documented the problems that can occur and the conditions that need to be in place for effective contracting out. These authors implicitly present a contingency theory of privatization in that they suggest the contingencies that managers have to deal with in successful privatization initiatives. As suggested in Exhibit 14.4, they tend to emphasize such contingencies as the following:

- Having a range of contractors submit competitive bids for the contract, to avoid monopolistic bidding situations

- Effectively managing strong employee or union opposition to the contract (see “People” under “Process” in Exhibit 14.4)

- Carrying out effective precontract planning and analysis, including such precautions as well-developed cost comparisons and meetings with potential bidders

- Establishing effective contracts, with clear stipulation of goals and performance criteria and provisions for monitoring, evaluation, incentives, and sanctions, which must include consideration of equity, effects on the community, social goals, and other typical public sector issues

The professional literature emphasizes contingencies such as these as well as the others indicated in Exhibit 14.4. Not all of them apply in all situations. For example, there may be situations in which effective relations with a single long-term contractor provide better results than soliciting competitive bids from many providers. Still, we now have a growing consensus on a set of contingencies to be managed in successful contracting out.

Recognizing and managing such contingencies thus becomes one part of excellence in public management. As suggested earlier, however, a more general objective of Exhibit 14.4 is to illustrate an approach to privatization that involves a comprehensive and well-developed approach to organizing for the challenge and managing it. The suggestions in the exhibit are limited by space and time and could be richly expanded with ideas from the earlier chapters. For example, one could approach privatization initiatives as matters of change management, drawing on the ideas in Chapter Thirteen about managing successful change. One could combine change management with a strategic planning process that focuses on privatization and contracting out specifically, or one could draw those topics into a broader strategic plan to coordinate privatization with the overall organizational strategy. In dealing with how privatization affects the culture of one’s organization, one could draw on the discussion in Chapter Eleven about leadership and culture, with its ideas about how leaders can influence such matters as employee concerns about privatization initiatives and how they mesh with their agency’s mission and values. In these and many other ways, the framework for the book and the deeper treatment of its components illustrate another view of privatization (perhaps a limited one that managers and researchers will revise or even discard in favor of a better one) as a challenge to excellence in organizing and managing in the public sector.

Conclusion

The foregoing discussion of the management of privatization initiatives and programs emphasizes the general point that although the concepts, theories, and ideas covered in this book do not offer a scientific solution, they can certainly support the development of a well-conceived, well-informed orientation toward excellence in public organization and management.

It is consistent with the theme repeatedly stated in this book that its conclusion should be brief. Effective understanding and management of public organizations do not sum up neatly into a set of snappy aphorisms. The preceding examples are intended to illustrate ideas and topics developed in earlier chapters of the book, which have been applied as comprehensively as possible to management initiatives. The framework offered in this book may need some improvements for some people and for various situations, but knowledge of the ideas and materials herein should still be valuable to those with a sustained commitment to excellence in public management. Ultimately, it is the general determination to maintain and improve public management that remains essential.

The government of the United States, including all of its levels and adjoining private activities, amounts to one of the great achievements in human history. Like private and nonprofit organizations, public organizations routinely provide beneficial services that would have been considered miracles a century ago. Yet they also have the capacity to do great harm and impose severe injustice. The viability and value of government depend on legions of managers, employees, supporters and critics, who share a determination that this great institution will perform well, and that through its performance the nation will prosper.

- Key terms

- Discussion questions

- Topics for writing assignments or reports

- Case Discussion: The Case of the Crummy Contract

- Case Discussion: The Case of the Vanishing Volunteers

Note

1. Books and articles that discuss effective public management, or report empirical evidence of it, or that emphasize an important role for public managers in governance, include the following: Beam, 2001; Behn, 1994; Borins, 1998, 2008; Cohen and Eimicke, 1995; Denhardt, 2000; DiIulio, 1989, 1994; Doig and Hargrove, 1987; Gold, 1982; Halachmi and Bouckaert, 1995; Hargrove and Glidewell, 1990; Holzer and Callahan, 1998; Ingraham, 2007; Jreisat, 1997; Kelman, 1987, 2005; La Porte, 1995; Light, 1997; Linden, 1994; Meier and O’Toole, 2006; Moore, 1995; Moynihan and Pandey, 2004; O’Toole and Meier, 2011; Poister, 1988b; Popovich, 1998; Porter, Sargent, and Stupak, 1986; Riccucci, 1995; Tierney, 1988; Wilson, 1989; Wolf, 1993, 1997.