FIFTEEN

Popular and Influential Management Books

A QUICK TRIP through any bookstore shows that the public’s interest in reading business books might only be exceeded by the willingness of gurus, academics, and executives to write them. Amazon currently sells more than 250,000 books categorized as “Management and Leadership.” Simply based on sales, a number of these books appear to have captured the attention of managers in the United States and around the world. There are also numerous examples of books without seven-figure sales whose ideas have helped shape business practice. This chapter investigates whether popular and influential management books are written by university-based researchers and addresses the prospect of translating organizational research to managerial practice through management books.

The degree to which popular management books are based on sound research has been hotly debated. Over the past several decades academics and other commentators have regularly criticized popular business books for presenting unsupported conclusions and poor quality research (e.g., Pierce, Newstrom, & Cummings, 2002). Despite their sales, popular business books in general have been widely panned by academic researchers as presenting simple prescriptions, promoting trademarked phrases, and repackaging common wisdom (Argyris, 2000; Rosenweig, 2009). Popular business books are often viewed as advertisements for seminars or consulting rather than as actual prescriptive ideas based on theory and research.

To better understand how university-based researchers are competing in this marketplace for managers’ attention, I collected information on books listed on the Business Week best-seller list from 1997 to 2009 and six different “best of” or “most influential” lists published from 1997 to 2009. These data suggest that although consultants and gurus dominate the mega–best sellers and popular culture business books, management books written by academics are an important market segment. I found that although most best-selling books are written by consultants and gurus, 25 percent of the Business Week best sellers in management from 1997 to 2009 were written by university-based authors. For the 58 management books published since 1970 that are cited on “best” and “most influential” lists, nearly 75 percent were written by authors with university appointments. I also found that management books written by academics were significantly more likely to be cited in practitioner journals and human resources (HR) trade publications than those written by consultants and gurus. In the following pages, I investigate which management books are popular; which have been influential; and how often these books are cited in the popular press, practitioner-oriented journals, and trade magazines. Finally, I review some of the writing on popular and influential management books and offer some thoughts on the prospects for research-to-practice transfer through management books.

Which Books Are Popular?

Coming up with a list of the most popular management books of all time is difficult because there are no agreed-upon or centralized means to track book sales across eras. Contemporary methods of tracking book sales by register scans (e.g., Neilson BookScan) have only been around since the 1990s, and most book sales claims come from authors and book jackets. Of all the business books that are published annually, there are a relatively small number that break through into popular culture and become mega–best sellers. Books such as The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, Who Moved My Cheese? and What Color Is Your Parachute? rank among the highest selling books of all time. Other self-reported best sellers include In Search of Excellence with 6 million sold and Good to Great with 4.5 million copies sold.

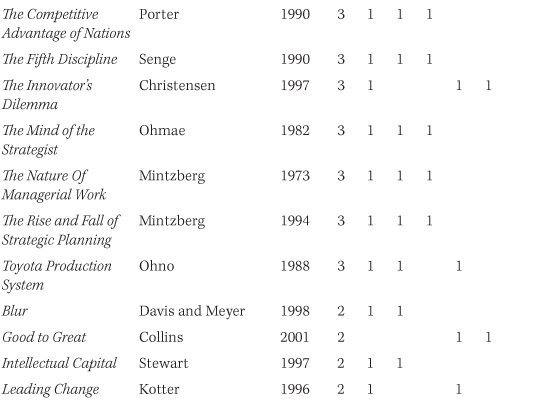

The 625 different books that appeared on the Business Week best-seller lists from 1997 to 2009 are a mixture of new releases and old favorites. In fact, consistency in the list of top sellers over the years led Business Week to begin a separate list for “Long-Running Best Sellers” for both paperbacks and hardcover books in the early 2000s. Relatively few of the books on the Business Week list, however, actually deal with management, strategy, and leadership. Books on management topics make up only 17 percent of the total and are overshadowed by a huge number of books on personal finance, investment strategies, and self-help. University-based authors were responsible for around a quarter of the best-selling management books (management, strategy, and leadership). Table 15.1 lists the management best sellers written by authors with current or past university affiliations.

TABLE 15.1 Business Week Best Sellers, 1997–2009, by Authors with University Affiliations

Which Books Are Influential?

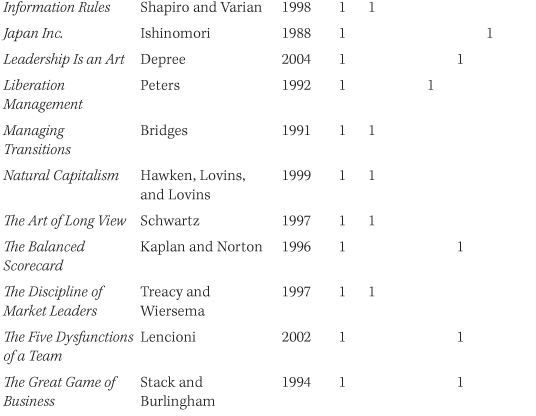

To gauge which books managers rate as influential, I surveyed executives and examined published lists of “best” or “most influential” business books. First I worked with the eePulse company based in Ann Arbor, Michigan, to pose the question to a large sample of executives through the Leadership Pulse survey. The Leadership Pulse is a short-format survey regularly conducted with a group of more than 10,000 self-selected executives. These executives are primarily based in the United States and represent a variety of industries and functional backgrounds. A single question was added to a regular survey conducted in January 2010 that asked, “We would like some nominations for books that have had the greatest impact on your management practice or leadership style.”

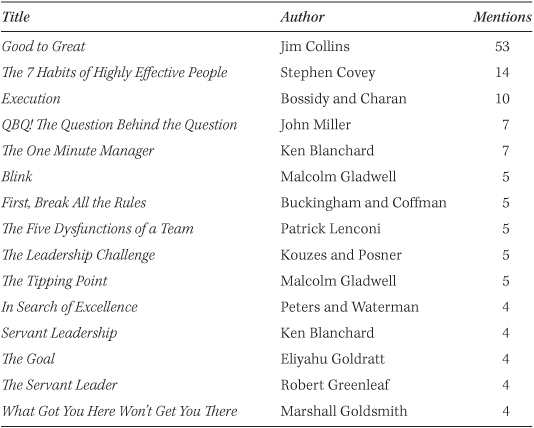

Of the 470 survey respondents, 300 executives listed a total of 224 different books. As an indicator of the inherent subjectivity of what makes a “best” business book, only 44 books were cited by more than one respondent. The list of books most often cited as influential largely overlaps with the Business Week best sellers over the last 12 years. All 15 books listed by four or more respondents also appeared on the Business Week best-seller lists from 1997 to 2009. (See Table 15.2.)

TABLE 15.2 Leadership Pulse Survey of “Best” Books with More Than Three Mentions

As a second measure of the influence of management books, I used existing “all time” and “most influential” lists. I compiled six “best” lists from various sources which contained a total of 166 books. Each of the lists was selected based on different criteria, but focused on some combination of the most “important,” “influential,” or “best” business books of all time. Of the 166 books on the influential lists, approximately half (81) could be categorized as management topics. The six “best” lists included the following:

![]() The 100 Best Business Books of All Time (2009) New York: Penguin.

The 100 Best Business Books of All Time (2009) New York: Penguin.

![]() The Best Business Books Ever (2007) New York: Bloomsbury.

The Best Business Books Ever (2007) New York: Bloomsbury.

![]() Business: The Ultimate Resource (2002) Cambridge, MA: Perseus.

Business: The Ultimate Resource (2002) Cambridge, MA: Perseus.

![]() “Best Business Books of the 20th Century” (2000) New York: HarperBusiness.

“Best Business Books of the 20th Century” (2000) New York: HarperBusiness.

![]() “20 Most Influential Business Books from 1981–2000” (2000) New York: Forbes.

“20 Most Influential Business Books from 1981–2000” (2000) New York: Forbes.

![]() The Ultimate Business Library (1997) New York: AMACOM.

The Ultimate Business Library (1997) New York: AMACOM.

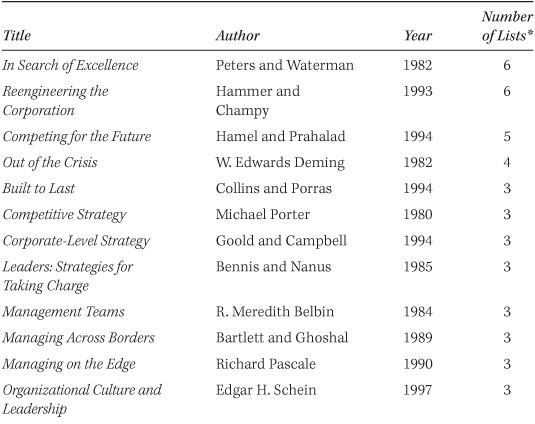

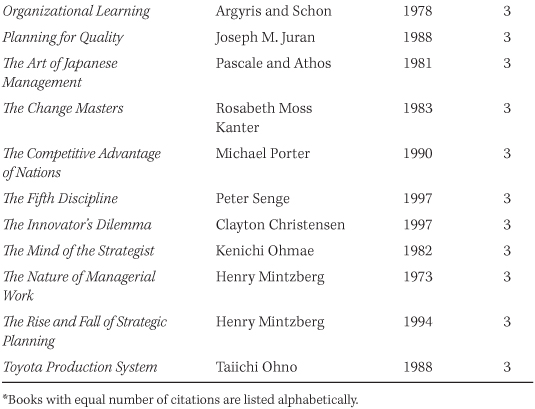

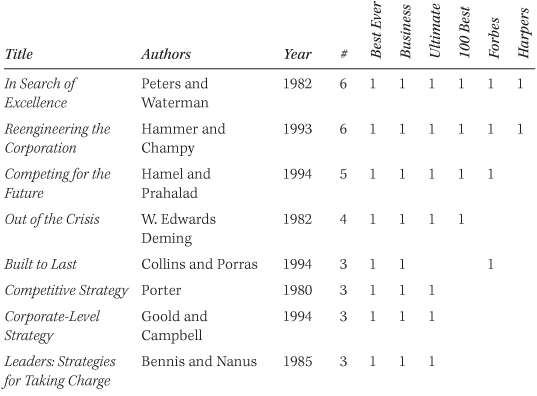

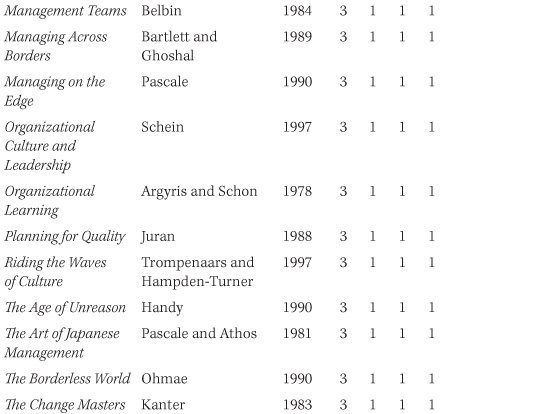

Table 15.3 details the management books published after 1970 that appeared on three or more of the “best” lists (see the Appendix later in this chapter for a complete list of the “best” books). Although there was significant divergence across the lists, a small number of important books appeared on multiple lists. Two books, In Search of Excellence and Reegineering the Corporation, appeared on all six lists. Competing for the Future appeared on five of the lists and Demming’s Out of the Crisis appeared on four. These influential books are twice as likely to be written by university-based authors as the Business Week best sellers.

Half of the 58 management books published after 1970 that appear on the influential lists were written by authors holding university positions. Although these individuals vary in the degree to which they might be called traditional academics, they all have (or have had) university affiliations.

“Most Influential” Authors with Current University Appointments

Chris Argyris

Joseph Badaracco

Christopher Bartlett

R. Meredith Belbin

Warren Bennis

Leonard Berry

Adam Brandenburger

Clayton Christensen

Reg Evans

Sumantra Ghoshal

Daniel Goleman

Rosabeth Moss Kanter

Robert Kaplan

John Kotter

James Kouzes

Henry Mintzberg

Barry Nalebuff

Ikujiro Nonaka

David Norton

William Ouchi

Jeffrey Pfeffer

Michael Porter

C. K. Prahalad

Barry Posner

Edgar Schein

Donald Schon

Peter Senge

Robert Sutton

Hirotaka Takeuchi

Noel Tichy

Michael Useem

TABLE 15.3 Most Commonly Listed “Best” Management Books, 1970–2009

Another 15 books were written by former academics or individuals with previous university affiliations. Notable gurus counted among the “former” academics include Tom Peters, who spent “seven years at Stanford Business School to get my PhD in organizational behavior,” as well as Gary Hamel (London Business School, Michigan, and Harvard) and Michael Hammer (Massachusetts Institute of Technology). Also included in this list is Jim Collins, who was formerly on the faculty at Stanford.

Which Books Transfer to Practice?

To better gauge the diffusion of the different books into popular culture, HR practice, and teaching through business journals, I searched for mentions of the popular and influential books in three different types of publications. Full text searches were done for the book titles and in some cases the first author’s last name. Articles that mentioned the book were counted and used to compute citations per year since the books were published (or since 1984 for older books). First, newspapers and magazine articles were searched using LexisNexis to search major U.S. publications. Second, ABI/Inform was used to search Training and Development magazine and HR Magazine. Third, mentions in business journals were collected for: Harvard Business Review, Sloan Management Review, and Organizational Dynamics.

Data on the number of mentions in these publications suggest that these three types of publications (popular press, practitioner journals, and HR trade associations) tend to focus on different types of books and authors. General newspapers and magazines are most likely to mention books written by nonacademic consultants and gurus with 19.72 mentions per year for the average book published. However, books written by academically affiliated authors were close behind with an average of 15.46 mentions per year. Actual managers (in the form of ex-CEOs and billionaires) were the least likely to be mentioned in newspapers and magazines. These data indicate that although academic books cited as “best” or “influential” have gained some traction, the mass media still gravitate toward books written by consultants and gurus.

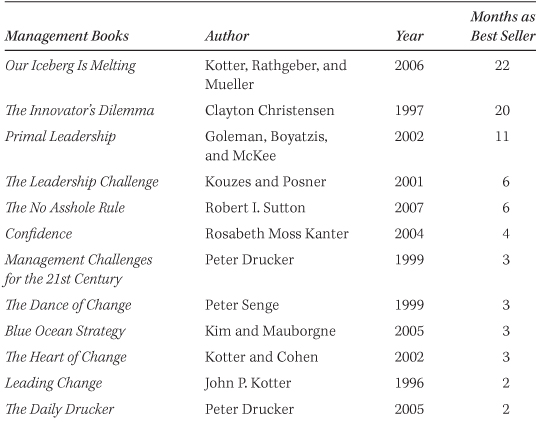

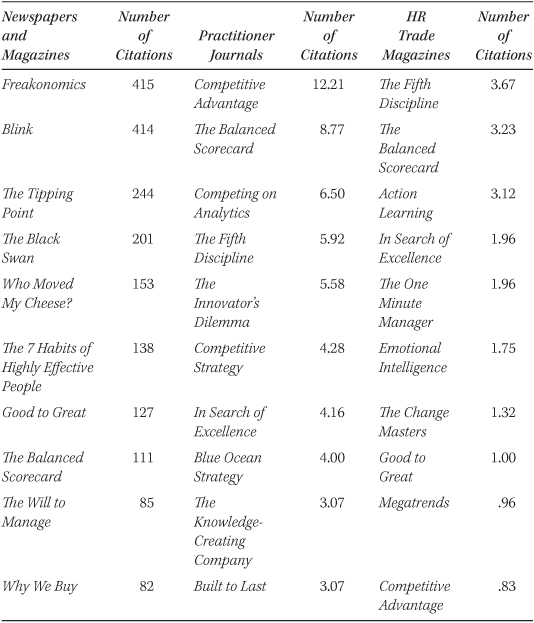

A different pattern emerges, however, when examining which books are mentioned in practitioner journals and HR trade magazines. Books written by authors with academic affiliations are two and a half times more likely to be mentioned in practitioner journals such as Harvard Business Review and more than twice as likely to be mentioned in HR trade magazines than books written by consultants and gurus. (See Table 15.4.)

Examining the ten most mentioned books in each of these three types of publications further illustrates these differences. Newspapers and magazines were far more likely to mention books that have crossed over into popular culture such as Freakonomics, The Tipping Point, Blink, and The Black Swan. When newspapers and magazines mention management books, they are most likely to mention the most popular books written by consultants including Who Moved My Cheese? and The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.

TABLE 15.4 Book Mentions per Year by Author for Influential Management Books

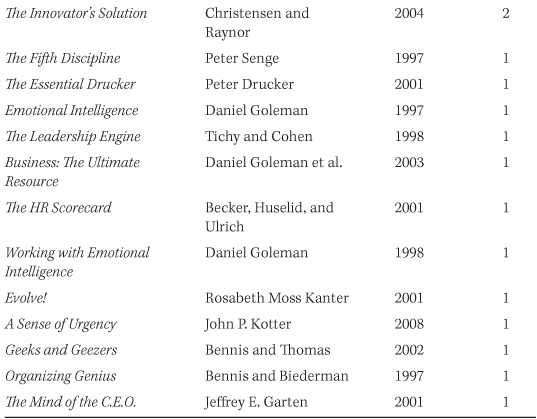

The books most often mentioned in practitioner journals and HR trade magazines, on the other hand, are dominated by books written by academics. Eight of the ten books most often appearing in practitioner journals were written by university-based researchers, with books by Harvard faculty appearing most frequently. Among all the popular and influential management books investigated, The Balanced Scorecard stands out as one of the most frequently mentioned across all three types of publications, indicating the broad impact of this book on popular culture, teaching and HR practice. (See Table 15.5.)

What Makes a Book Popular or Influential?

Given the number of business and management books that are published annually, it is difficult to say definitively what causes a business book to break through to mass popularity. The role that news media and marketing play is clear from watching the success of books such as Freakonomics and Blink, which have been featured in popular magazines and newspapers at least daily (on average) since they were released. Word of mouth and popular appeal also play a role. Peters and Waterman were apparently surprised by the mass sales of 1982’s In Search of Excellence. The publishers were unhappy when McKinsey distributed 15,000 prepublication copies of the book, thinking that the authors had given away a significant proportion of their potential sales (Newstrom, 2002). It turns out that these prepublication copies primed interest in the book as people wanted to know what everyone was talking about. Although it is difficult to peer into the black box of popular appeal, the mass market management books appear to have some characteristics in common.

TABLE 15.5 Top 10 Citations per Year for Popular and Influential Management Books

Notoriety

For popular books in particular, the number one factor in book sales appears to be the author’s notoriety. The influence of notoriety is clear, for example, when looking at the number of billionaires, CEOs, and other famous people who have published business best sellers over the past 12 years. Twenty-six different CEOs (and former CEOs) published Business Week best sellers from1997 to 2009. The list also includes a number of coaches, politicians, and others who have translated their fame into best sellers.

The Business Week best-seller lists over the past 12 years also reveal multiple repeat authors. These are authors who have created their own brands and books series around certain topics. Among management consultants, serial authors include Ken Blanchard (seven books) and Steven Covey (five books). Tom Peters and Jim Collins have built audiences that vault any new release onto the best-seller lists. Among university-based authors, Michael Porter and Warren Bennis have created personal brands for all their books.

Target Audience

The most popular business books of all time and the very top sellers in the Business Week list are all geared toward mass audiences. Books such as The One Minute Manager, Who Moved My Cheese? and Getting to Yes! tend to straddle the line between management and self-help and are widely read by more than business people. Sales are also driven by the integration of the material into common corporate training classes. Who Moved My Cheese? is a parable on coping with change that is easy to ask participants to pre-read and is regularly used in both in-house training and off-the-shelf courses; it claims sales of more than 20 million copies. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People has been integrated into a series of course offerings widely offered in Fortune 500 firms.

Timing

Many of the books cited as “best” or most “influential” reflect the times in which they were published. The early 1980s was a time of transformation in American manufacturing, in which a competitiveness gap was perceived and the economy was easing out of a recession and the “malaise” of the 1970s. It was a perfect time for In Search of Excellence, which provided some specific prescriptions and optimism that large corporations could be transformed with “a bias for action” and willingness to challenge bureaucracy. The other most influential books of the 1980s dealt with quality (Out of the Crisis; Planning for Quality) and Japanese management (The Art of Japanese Management; Japan Inc.).

Similarly, the 1990s were a time of rapid technological change, internationalization, and evolution toward a knowledge- and service-based economy. The internet revolution and tech bubble were in full swing and books such as Complexity, The Knowledge-Creating Economy, and Intellectual Capital reflected the zeitgeist. Disruptive technologies were on everyone’s mind when The Innovator’s Dilemma was released in 1997. The most influential books of the times reflect the times but also help to define certain ages in retrospect.

Style

Although the most popular and influential management books of all time are generally defined by a “breakthrough idea,” many are also notable for their simplicity. Newstrom (2002) notes, “Many books that were successful in the marketplace, selling millions of copies and sustaining interest over a period of years had one distinguishing feature above all others: readers could reiterate their major conclusions or recommendations in very few words.” Pagel and Westerfelhaus (2005) conducted a detailed analysis of the reading habits of managers and concluded that above all else they preferred simple “business” writing and expressed distaste for “academic” writing. The preferred writing is characterized by “(a) short length, (b) concise word usage, (c) direct presentation of main points, (d) the presence of concrete examples and/or the absence or abstract concepts, and (e) simple language” (p. 430).

Are They Based on Research?

The management, strategy, and leadership books published by university-affiliated authors and reviewed for this study cover a wide range of topics and vary significantly in the degree to which they are based on research. For example, Goleman’s original Emotional Intelligence largely presents the work of other brain researchers as derived from peer-reviewed articles, whereas the follow-up Working with Emotional Intelligence presents original work. Bob Sutton’s The No Asshole Rule, described by Publishers Weekly as “meticulously researched,” aligns with academic research but is largely supported with nonacademic examples. Kim and Mauborgne’s Blue Ocean Strategy uses a series of case studies to illustrate their theory developed in a series of papers published predominantly in Harvard Business Review. The contrast in the degree to which they are research based is particularly stark among the Business Week best sellers from 1997 to 2009. The Innovator’s Dilemma presents the details of Christensen’s groundbreaking research on organizational survival in the disk storage industry, whereas Kotter’s Our Iceberg Is Melting is a parable about organizational change that details the ground breaking beneath a group of penguins.

Moving beyond the books by university-affiliated authors, any discussion of management books, research, and practice must acknowledge that the best-selling management books of all time (and many of those cited as best or most influential) are not research based. They do not present research findings and in many cases do not suggest that the books are based on anything more than personal observation. Some popular books have been criticized as not only unsupported by research but actually spreading bad advice (Argyris, 2000).

Of all the management books over the last 40 years, Peters and Waterman’s In Search of Excellence is the leader in simultaneously capturing the attention of managers and the derision of business researchers. The publication of In Search of Excellence is commonly cited as a watershed for business publishing and the market for business gurus in general. The eight easy-to-understand principles with explanatory examples have generated a whole series of similar books over the last 30 years that presents a set of defining principles or characteristics of high-performing companies.

The book was also notable in presenting the eight attributes based on empirical research used to identify the companies. The book describes how the In Search of Excellence companies were identified by assessing objective performance measures. This same formula has since been applied in a number of other popular and influential books most notably Built to Last (Collins and Poras) and Good to Great (Collins). The research used to select the companies and the practices for In Search of Excellence was criticized almost immediately (“Oops! Who’s Excellent Now?” Business Week, 1984) and has been the subject of several systematic critical analyses in the 27 years since its publication (e.g., Hitt & Ireland, 1987; Rosenzwieg, 2009).

It now appears that the methods to select the companies were less systematic than presented. In 2001, an article appeared in Fast Company with Peters on the byline that contained the admission that “I confess: We faked the data.” Peters wrote:

Search started out as a study of 62 companies. How did we come up with them? We went around to McKinsey’s partners and to a bunch of other smart people who were deeply involved and seriously engaged in the world of business and asked, Who’s cool? Who’s doing cool work? Where is there great stuff going on? And which companies genuinely get it? That very direct approach generated a list of 62 companies, which led to interviews with people at those companies. Then, because McKinsey is McKinsey, we felt we had to come up with some quantitative measures of performance.

Peters was surprised by the negative publicity over the admission and quickly backtracked by claiming that he had been the victim of an “aggressive headline” and that the words had come from Allan Weber, Fast Company senior editor who had actually written the article after lengthy interviews with Peters. “Get off my case . . . We didn’t fake the data,” Peters later said (Byrne, 2001). Peters writes:

Was our process fundamentally sound? Absolutely! If you want to go find smart people who are doing cool stuff from which you can learn the most cutting-edge principles, then do what we did with Search: Start by using common sense, by trusting your instincts, and by soliciting views of “strange” (that is, unconventional) people. You can always worry about proving the facts later.

The primary criticism leveled against books with high-performance principles and other books is that company examples are selected first and the measures used to identify the companies are reverse engineered. Jim Collins describes that for Good to Great, the 11 companies were selected in part based on superior stock returns and that the conclusions drawn come “directly from the data” (p. 10). Although making no criticism of the practices that good companies use to transform themselves into great ones, Resnick and Smunt (2008) attempted to reproduce Collins’s results and concluded that the selection of the companies was most likely “data-mining.”

However, the influence (and sales) of these books is undeniable and a detailed critique of their methods may be missing the point. The practicing manager values research differently than university faculty, and the success of these books has created a market and opened up the discussion as to what the “high-performance” practices should be. Julia Kirby (2005), senior editor at Harvard Business Review, summarized the impact of In Search of Excellence:

As management consultants, Peters and Waterman sat at the intersection of scholarship and practice, and cast the gauntlet down in each direction: They challenged managers by claiming that varying managerial actions and attributes could account for the differences between winners and losers. At the same time, they challenged researchers by claiming that the problem of isolating the drivers of high performance was tractable. Did they get the answers right? Probably not. . . In the end the impact of In Search of Excellence is less that it solved the problem than that it put the problem on the table.

Prospects for Research Transfer

A great deal of frustration and pessimism has been expressed among management scholars in writing, conferences, and this book over the difficulty they have in transferring research findings into practice through traditional outlets, including management books. It is clear that more academic researchers have a difficult time competing with consultants, journalists, gurus, and former CEOs in both book sales and name recognition. However, I think many researchers both overstate the actual impact of popular business books and discount the role that rigorous research has played in the evolution of management practice in today’s large organizations around the world.

Granted, there are well-documented examples of Business Week best sellers that have helped to spread ideas that not only lack research support but may actually be damaging in practice. Forced ranking systems, overuse of short-term incentive rewards or stock-based compensation, and a fixation on “total quality” and “reengineering” have all been popularized through business books with significant negative repercussions. However, many of the popular business books that have drawn criticism from management researchers have either limited application to practice or actually align with practices supported by rigorous research. While instructive fables (e.g., “the hedgehog”) and platitudes (e.g., “think win/win”) are easy to remember and appealing, they are not particularly actionable. In many cases, the criticism leveled against popular management books is not against the practices they advocate but the methodology used to derive them. Setting clear goals, using validated selection practices, and creating a culture of empowerment are all sound practices supported by research—regardless of how the authors arrived at the conclusions.

Focusing on best sellers to compare the impact of academic versus popular management books also might not be the best measure of the transfer of research to practice. First of all, many research-based books by academic authors are intended for smaller audiences of professionals in human resources, organizational development, training, and other specialized areas rather than managers in general. For example, it is clear that books such as HR Champions, The HR Scorecard, and Beyond HR have changed the way that HR managers think about practice even though they have sold a fraction of the biggest best sellers. The notion that academic authors cannot compete with mass market business books ignores the fact that there have been many innovations in employee selection, organizational design, team-based work, goal setting, training, job design and other practices over the past several decades with firm peer-reviewed research foundations and adopted by managers in part because of books that were not best sellers or on all-time lists. The widespread use of goal setting, team-based work, or high-involvement work practices in manufacturing has had positive impacts on organizations but represents an accumulation of research and writing in many formats rather than a single breakthrough book.

For many researchers such as Beer, Prahalad, Lawler, and Gratton represented in this book, works targeted toward practitioners serve as punctuation points or summaries of a career’s worth of work that also includes academic and practitioner journal articles, teaching, cases, textbooks, consulting, speeches, and interviews. I suggest that genuine changes in management practice are more likely to emerge from this steady drumbeat of examples and findings rather than the single best-selling books. The presentation and repetition of research findings across formats allows managers of different generations, educational backgrounds, and industries to discover and apply the principles in ways that suit them best—whether that comes from a 300-page book or a short workbook and diagnostic survey.

There are many good examples of research transfer through books, but organizational researchers should note the popularity of recent books on the psychology of decision making. Half of the popular books on decision making are written by academics who effectively translate peer-reviewed research for managers. Another third of the best-selling books on decision making are by professional writers, such as Malcolm Gladwell, who read academic research and repackage it for mass consumption. Robert Cialdini is a great example of programmatic research-to-practice writing; his two books on the Business Week list (Influence and Yes!) on the psychology of persuasion are supported by numerous original peer-reviewed articles and a textbook.

The findings presented in this chapter should be tempered by numerous limitations of measuring and comparing the popularity and influence of business books. First, this research ignores the large market in textbooks, which are not only “best sellers,” but also important formats for transferring research to practice. Second, the lists of “best” or “influential” are inherently problematic, and no doubt important books have been left off and books have been included that are idiosyncratic to particular lists. Similarly, categorizing the popular and influential books by subject was arbitrary in certain cases. I categorized academic authors by whether they had a faculty affiliation, but the distinction between academic and consultant or guru is inexact and subjective. Finally, selecting only best sellers and “best of all time” lists also focuses on single books by individuals and overlooks the changes in business practice that are based on cumulative research and writing. For example, very few of the books identified as most influential dealt with work teams, job design, and incentive rewards, whereas the arguably largest change in business practice over the last 30 years has been the adoption of “highperformance” work practices in the United States and Europe.

Given the intense competition in the marketplace for business books, are management books a viable means to transfer organizational research into practice? In 2002, Pfeffer and Fong conducted a similar analysis of popular and academic business books and concluded that, “only a small fraction of the business books that presumably influence management are actually written by academics” and that “business books are not a major source of books that directly influence management thought” (p. 87). I would suggest that although consultants and gurus dominate the mega–best sellers and popular culture business books, management books written by university-based academics are more likely to be cited by journals specifically oriented towards managers and are more likely to be cited as influential over the long term. So even though management books written by university researchers have a tough time competing for mind share among the general public and practitioners, there is reason to believe that management books are a viable and important means to transfer academic research to practice.

Appendix

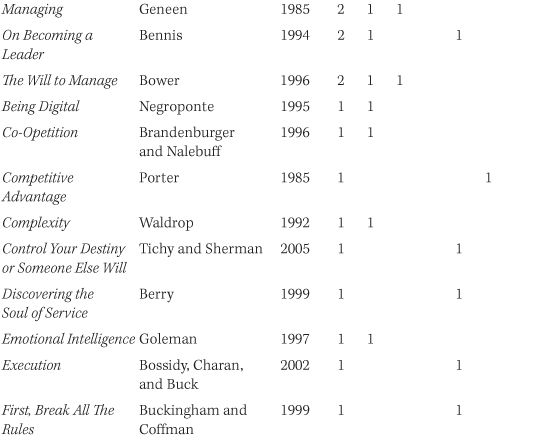

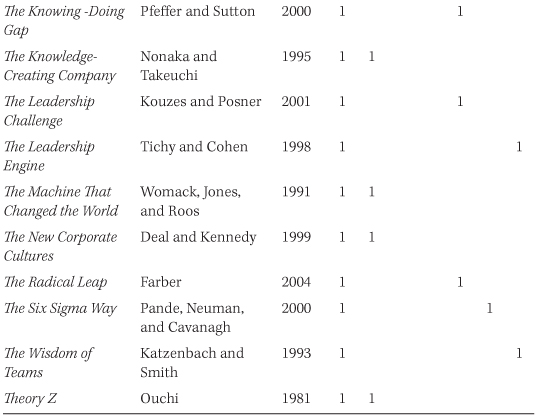

Management Books Published Since 1970 on “Best” Lists

RESEARCH APPROACH

I examine which business books are popular based on Business Week bestseller lists from 1997 to 2009. The source of the Business Week best-seller data is proprietary and the list has changed format over the years. For each of the 625 books I investigated the degree to which they (1) dealt with management topics and (2) were written by current and former academics. Second, using frequent appearance on “best of” lists as a proxy for influence, I compiled a list of 161 books cited among the most influential of all time. I also categorized these books by subject and collected data on whether these books were written by current and former academics. Finally, I gathered citation counts on popular and influential management books in various publications to gauge the size of their impacts on business practice. I counted the number of times the books were mentioned in popular newspapers and magazines, HR trade magazines (e.g., HR Magazine), and academic bridge journals (e.g., Harvard Business Review) to better understand the pathways through which popular and influential business books written by academics and nonacademics might influence business practice.

REFERENCES

Argyris, C. (2000). Flawed advice and the management trap. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Byrne, J. (2001, December 3). The real confessions of Tom Peters. Business Week.

Hitt, M., & Ireland, D. (1987). Peters and Waterman revisited: The unending quest for excellence. Academy of Management Executive, 1(2), 91–98.

Kirby, J. (2005). Toward a theory of high performance. Harvard Business Review, 83(7), 30–39.

Newstrom, J. (2002). In search of excellence: Its importance and effects. Academy of Management Executive, 16(1), 52–56.

Pagel, S., & Westerfelhaus, R. (2005). Charting managerial reading preferences in relation to popular management theory books. Journal of Business Communication, 42(4), 420–448.

Peters, T. (2001, November 3). The real confessions of Tom Peters. Fast Company.

Pfeffer, J., & Fong, C. T. (2002). The end of business schools? Less success than meets the eye. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 1, 78–95.

Pierce, J., Newstrom, J., & Cummings, L. L. (2002). Reflections on the best sellers: A cautionary note. In J. Pierce & J. Newstrom (Eds.), The manager’s bookshelf: A mosaic of contemporary views (pp. 25–30). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Resnick, B., & Smunt, T. (2008, November). From good to great to . . . Academy of Management Perspectives, 6–12.

Rosenzwieg, P. (2009). The halo effect . . . and eight other business delusions that deceive managers. New York: Free Press.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

George S. Benson is an Associate Professor at the University of Texas at Arlington and an Affiliated Researcher with the Center for Effective Organizations. George earned his PhD from the University of Southern California in the Marshall School of Business. He also holds degrees from Washington and Lee University and Georgetown University. He previously worked as a research analyst at the American Society for Training and Development in Alexandria, Virginia.