EIGHTEEN

How Business Schools Shape (Misshape)

Management Research

BUSINESS SCHOOLS (BSs) are the professional home of most management researchers. Consequently, they can have an enormous effect on the conduct and output of faculty research and, ultimately, on whether it is useful for theory and practice. Recently there has been considerable criticism and debate about BSs’ mission, operation, and value to students, business firms, and larger society (e.g., Bennis & O’Toole, 2005; Khurana, 2007; Mintzberg, 2004; Pfeffer & Fong, 2002; Starkey & Tiratsoo, 2007). Concurrently, there have been spirited discussions about the relationship between management research and practice—whether management research should contribute to theory and practice, the extent to which it does, and how this can be accomplished (e.g., Ford et al., 2005; Hambrick, 1994; Huff, 2000; Rynes, Bartunek, & Daft, 2001; Starkey & Madan, 2001; Van de Ven & Johnson, 2006; Walsh et al., 2007).

In this chapter, we draw on these different perspectives to identify key forces affecting BSs today. We show how those forces shape important aspects of BSs, which in turn influence the kind of management research that is conducted. This provides a clearer picture of the barriers and enablers that exist in BSs to produce knowledge that is useful for theory and practice. We focus on management research, such as human resource management, organizational behavior, organization theory, and strategy. Research from other disciplines in BSs, such as accounting, finance, and marketing, tends to translate more directly into practice than management research. We also center our discussion on BSs that are located in research universities, where most management research is produced.

Based on the material in this book, we first briefly review the features of research that is useful for theory and practice. This review provides a reference point for discussing how BSs can inhibit or promote that approach to inquiry. Next, we identify forces having a significant effect on BSs’ functioning and performance and show how they can create, often unintentionally, barriers to doing research for theory and practice. Finally, we identify ways that BSs can overcome these barriers and enable this form of research.

Research Useful for Theory and Practice

Evident throughout this book is the considerable attention that has been paid to understanding how management research can contribute to theory and practice (see Chapter 1, Research for Theory and Practice). Referred to as “action research” (Lewin, 1946), “engaged scholarship” (Van de Ven & Johnson, 2006), “action science” (Argyris, Putnam, & Smith, 1985), or “collaborative research” (Adler, Shani, & Styhre, 2004), among other names, this action-oriented research has features that promote joint contributions to theory and practice (see Chapter 8, Making a Difference and Contributing Useful Knowledge; Chapter 4, A Ten-Year Journey of Cooperation; and Chapter 2, Crossing Boundaries to Investigate Problems in the Field). This type of research is characterized by the following features:

![]() Rigorous and relevant. This research explicitly seeks to create knowledge that is both rigorous and relevant. It applies scientific methods to collect and analyze data and test theories, while striving to capture the conditions and reality that practitioners face.

Rigorous and relevant. This research explicitly seeks to create knowledge that is both rigorous and relevant. It applies scientific methods to collect and analyze data and test theories, while striving to capture the conditions and reality that practitioners face.

![]() Collaboration between researchers and practitioners. Action-oriented research is grounded in a collaborative partnership between researchers and practitioners. Both sides are actively involved in the research to varying degrees, from defining the research problem, to choosing appropriate methods and theories, to analyzing and interpreting the results, to applying them to theory and practice development. The effectiveness of this collaborative community rests on mutual trust, openness, and respect among participants. This promotes active listening and sharing different perspectives and expertise among members; it helps them constructively address conflicts that invariably arise when views and opinions differ; it takes full advantage of this diversity to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem.

Collaboration between researchers and practitioners. Action-oriented research is grounded in a collaborative partnership between researchers and practitioners. Both sides are actively involved in the research to varying degrees, from defining the research problem, to choosing appropriate methods and theories, to analyzing and interpreting the results, to applying them to theory and practice development. The effectiveness of this collaborative community rests on mutual trust, openness, and respect among participants. This promotes active listening and sharing different perspectives and expertise among members; it helps them constructively address conflicts that invariably arise when views and opinions differ; it takes full advantage of this diversity to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem.

![]() Messy problems grounded in practice. This research tackles complex real-world problems that are not easily understood or resolved. Such messy problems have multiple underlying causes that are interrelated in complicated ways. This complexity makes it extremely difficult to comprehend and address them applying the expertise of either researchers or practitioners acting alone. Messy problems need to be studied from multiple theoretical and practical perspectives using different methods and approaches. This interdisciplinary research permits triangulation of methods and views, which can lead to richer, more valid explanations and more effective solutions.

Messy problems grounded in practice. This research tackles complex real-world problems that are not easily understood or resolved. Such messy problems have multiple underlying causes that are interrelated in complicated ways. This complexity makes it extremely difficult to comprehend and address them applying the expertise of either researchers or practitioners acting alone. Messy problems need to be studied from multiple theoretical and practical perspectives using different methods and approaches. This interdisciplinary research permits triangulation of methods and views, which can lead to richer, more valid explanations and more effective solutions.

![]() Long-term and intense. Action-oriented research inherently takes time and energy both to create and sustain an effective partnership between researchers and practitioners and to understand and devise solutions to messy problems. Researchers and practitioners come from different professional cultures and it takes considerable time and effort to develop and maintain trust, openness, and respect between them. Moreover, this relationship is likely to be psychologically intense as participants share diverse views and confront and resolve the conflicts that invariably arise. It takes hard work to develop the strong social bonds needed for collaborative research, and the quality of the research outcomes depends heavily on the quality of the partnership. The nature of the research problem also demands long time commitments. Messy problems must be studied up close and over time to discover the causal mechanisms underlying them and to design, enact, and assess possible solutions. This requires substantial time collecting and analyzing data, testing different theories, and trying out possible solutions, particularly in the context of collaborative inquiry where participants must share, understand, and reconcile different perspectives.

Long-term and intense. Action-oriented research inherently takes time and energy both to create and sustain an effective partnership between researchers and practitioners and to understand and devise solutions to messy problems. Researchers and practitioners come from different professional cultures and it takes considerable time and effort to develop and maintain trust, openness, and respect between them. Moreover, this relationship is likely to be psychologically intense as participants share diverse views and confront and resolve the conflicts that invariably arise. It takes hard work to develop the strong social bonds needed for collaborative research, and the quality of the research outcomes depends heavily on the quality of the partnership. The nature of the research problem also demands long time commitments. Messy problems must be studied up close and over time to discover the causal mechanisms underlying them and to design, enact, and assess possible solutions. This requires substantial time collecting and analyzing data, testing different theories, and trying out possible solutions, particularly in the context of collaborative inquiry where participants must share, understand, and reconcile different perspectives.

Barriers to Research Useful for Theory and Practice

Given its dual focus on theory and practice, action-oriented research seems ideally suited to generating management knowledge in business schools. It provides both the rigor and relevance necessary to create scientific knowledge to inform good practice. It assures that business professionals will be guided by evidence-based knowledge that is applicable to the problems they face. Yet this form of inquiry is relatively scarce in BSs. Indeed, the kind of management research predominate today has almost the opposite characteristics. It is researcher driven and theory oriented. It applies rigorous methods to well-defined problems studied from afar over relatively short time frames. Relevance plays a secondary role as do practitioners who are treated as subjects and passive recipients of research knowledge rather than as collaborators. Typically, the research findings advance scientific knowledge while having modest to no consequences for management practice (e.g., Pfeffer & Fong, 2002; Rynes, Bartunek, & Daft, 2001; Starkey & Madan, 2001).

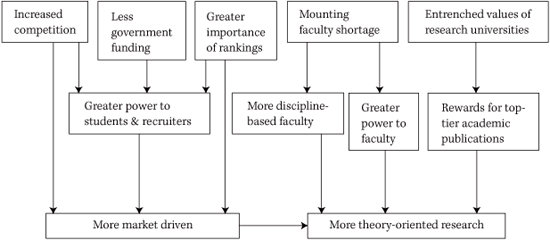

To explain how management researchers have come to eschew action-oriented research in favor of theory-oriented research, we examine how BSs influence the kind of research that faculty do. We organize this analysis around five powerful forces affecting BSs today: (1) increased competition, (2) less government funding, (3) greater importance of media rankings, (4) mounting faculty shortage, and (5) entrenched values of research universities. As shown in Figure 18.1, these conditions have set off a chain of events in BSs that results in particular forms of research being favored over others. This analysis reveals strong barriers to the kind of management research that is likely to be useful for theory and practice.

FIGURE 18.1 Forces Shaping the Kind of Research Encouraged in Business Schools

Increased Competition

Business schools are facing increased competitive pressures as their sheer number swells throughout the world (Starkey & Tiratsoo, 2007). Originating mostly in the United States and Canada, BSs have proliferated in recent years in Asia, Australia, Europe, Latin America, and the United Kingdom. Those in the top tier compete globally and nationally for students and funds, whereas others confront stiff local or regional competition. Add to this the growing number of organizations unaffiliated with established universities that are entering the business education market. Consulting and training firms, forprofit colleges, and corporate universities are all seeking inroads into business education, often through distance learning and other forms of nontraditional instruction. Realizing that business education is big business, they are extending their reach beyond executive education to business degrees (Pfeffer & Fong, 2004).

On the demand side, student applications and enrollments have become much more erratic and difficult to predict (Starkey & Tiratsoo, 2007). This can be seen in the fluctuating popularity of different kinds of degree programs, such as the full-time, part-time, and executive MBA programs. This volatility in demand has a lot to do with the rapidly growing global market for business education, in addition to jolts in the economy and job market. Not only are BSs proliferating globally but also is the sheer number of students from different countries seeking business degrees. This means that BSs are increasingly competing with schools from different countries for students worldwide. Changes in exchange rates, visa restrictions, disease patterns, political conditions, and the like can affect student demand for business education in complex and unpredictable ways. Thus, BSs are discovering that the global marketplace is far more complex and uncertain than the more traditional domestic market.

As shown in Figure 18.1, faced with increasing competitive pressures, BSs are becoming more market driven; they are also giving greater power to students and recruiters, which in turn feeds this market focus. These two aspects of BSs affect management research in the following ways.

More market driven

Faced with increasing competitive pressures, BSs have become far more market driven, paying greater attention to things like the bottom line, market share, industry reputation, and short-term results (Khurana, 2007; Trank & Rynes, 2003). This market focus is evident in the growing application of business rhetoric to BSs, where business education is referred to as an “industry,” students as “customers,” other BSs as “competitors,” and new programs as “revenue sources.” Faced with fierce global competition and uncertain student demand, BSs are aggressively cutting costs and seeking new ways to boost income. Class sizes, faculty pay, staff support, and infrastructure expenses are being closely scrutinized to minimize costs. Efforts to enhance revenues include increases in student fees, new educational programs and services, broader student diversity, overseas expansion, identity branding, and alliances with other BSs and corporations (Starkey & Tiratsoo, 2007).

The relationship between this market focus and faculty research is closely tied to the important role that research has come to play in determining BSs’ prestige. Starting with the Ford Foundation’s highly influential report in the late 1950s (Gordon & Howell, 1959), which admonished BSs for being too vocational and lacking a scientific knowledge base, BSs have put enormous resources and effort into becoming legitimate research institutions (Khurana, 2007). Typically, they have encouraged research that draws on and emulates established academic disciplines—theoretically based, methodologically sophisticated, and empirically sound (Pfeffer & Fong, 2002). This kind of research, which is generally published in top-tier academic journals, has become the gold standard and a primary determinant of BSs’ prestige (Armstrong, 1995; Armstong & Sperry, 1994; Becker, Lindsat, & Grizzle, 2003). Moreover, within the university, a BSs stature rests largely on its research eminence. Given the reputational benefits of research, the more market driven BSs have become, the more they favor and support the kind of inquiry just described. Theory-oriented research confers prestige on BSs, which translates into better students and faculty, more external funding, better job placements, and more resources and autonomy within the university.

Greater power to students and recruiters

Increased competition also has enhanced the power of students and recruiters, which in turn has contributed to BSs becoming more market driven. Students’ main reason to earn a business degree is the expectation of future career success, typically gauged in terms of compensation (Pfeffer & Fong, 2002). Thus, students seek to attend BSs with strong capabilities in career training and job placement. On the recruiting side, firms hire business graduates because they have been pre-screened for business achievement and acquired knowledge and skills to start a business career successfully. Therefore, recruiters want to hire graduates from BSs that excel at selecting and training students for career success.

Growing competition and more erratic enrollments have led BSs to become more and more responsive to student and recruiter needs. This responsiveness can be seen in how receptive they have been to student calls for more simplified teaching materials, less theoretical and more job-focused course-work, better job placement support, and reduced grade pressure (Rynes & Trank, 1999). BSs have been equally if not more responsive to recruiter demands for graduates with more vocational skills and technical training needed for early career success. All of this gives students and recruiters more influence over BSs’ decision making, which contributes to the short-term market focus we see in many schools today.

The challenge for BSs is balancing market-driven demands for prestige bestowed by theory-oriented research with student and recruiter demands for less theory and more job-related training. One solution that seems to be emerging, at least tacitly, is a two-tier faculty system that partly reconciles these conflicting demands. The top tier includes faculty who excel at research; because they have high career mobility, they receive high salaries, reduced teaching loads, generous research support, and tenure-track status. The second tier consists of more teaching-oriented faculty including the growing cadre of clinical and adjunct instructors, many of whom teach full-time. Because their career prospects are mainly in the local market, they have relatively modest salaries, large teaching loads, reasonable teaching support, and generally are not tenure track. This two-tier system helps to jointly optimize the research demands of academe and the vocational demands of students and recruiters. It enables BSs to gain the benefits of both theory-based research and job-relevant education.

Less Government Funding

As shown in Figure 18.1, another major force affecting BSs is the steady decline of public financial support for higher education. Over the past few decades in the United States, for example, federal support for higher education has decreased in constant dollars and percentage terms while demand has grown significantly (Beauvais, 2007; Sonnenberg, 2004). This has increased financial pressures on BSs and made them more reliant on student tuition, corporate donations, and company subsidies for employee tuition.

The growing financial dependency on students and companies has enhanced their power over BSs’ decision making, which in turn has added to BSs being more market driven. As discussed previously, BSs are paying closer attention to student and recruiter needs, so they can attract the best students and place them in the top companies. This market focus is particularly sensitive to BSs’ prestige because it affects with which schools students and corporations choose to associate. Given theory-oriented research’s contribution to schools’ prestige, growing financial pressures reinforce BSs’ support for this kind of research.

Greater Importance of Rankings

Probably the most visible factor affecting BSs today is the proliferation of rankings by popular magazines and newspapers. These publicly pit BSs against one another on such dimensions as student selectivity, diversity, and satisfaction; job placements, starting salaries, and recruiters’ assessments; and faculty research, alumni ratings, and financial return on student educational expenses. Although there has been considerable debate about the validity of these various rankings, they are highly visible and widely read and can have significant effects on BSs (e.g., Corley & Gioia, 2000; DeAngelo, DeAngelo, & Zimmerman, 2005; Fee, Hadlock, & Pierce, 2005; Khurana, 2007; Zimmerman, 2001). Students consider the rankings when they choose a school, as do alumni when they consider gift-giving, recruiters when they make hiring decisions, and new faculty when they choose which school to join. Rankings also can affect a school’s status and funding within its university. Therefore, administrators and faculty increasingly take rankings seriously and expend considerable time and effort to maintain their school’s ranking, move it higher, or stem a drop by trying to turn things around.

The explosive growth of media rankings contributes directly to BSs becoming more market driven. It forces them to compete intensely with each other for reputational advantages, which can be enormous. Rankings can affect the quality of students and faculty that BSs can attract, the success of student job placements, the amount of external funding, and a school’s status in the business education profession and within the university. These benefits positively feed on themselves, with high ranking promoting success and success promoting high ranking. Thus, rankings play an increasingly important role in decisions about curriculum, enrollment, and resource allocations. They also are motivating BSs to pay closer attention to their external image by investing considerable time and resources in public and corporate relations, alumni communications, career placement services, and in some cases, gaming the rankings to get a leg up on the competition.

The media rankings add indirectly to BSs’ market focus by giving greater power to students and recruiters. For example, the Business Week rankings, which arguably are the most influential, are heavily weighted by student and recruiter assessments. Consequently, BSs increasingly pay close attention to these key stakeholders’ feedback, so they can quickly counter any negative reactions that might adversely affect the rankings. It is common, for example, for schools to modify their curriculum and placement practices quickly when negative feedback is encountered. More proactively, BSs have been known to remind students that it is in their best interest to rate the school highly; they have given key recruiters preferential access to top students and special treatment during their recruiting efforts. These responses underscore the power that media rankings have given to students and recruiters; they show how market driven BSs have become in responding to their needs.

BSs’ hyperattention to media rankings is strengthening their support for theory-oriented research. Indeed, some of the rankings include measures of research impact. U.S. News and World Report’s rankings, for example, contain input from deans, which likely takes into account a school’s research stature (Pfeffer & Fong, 2002). Even the venerable Business Week recently added a measure of research influence to its rankings. There is evidence showing that student and corporate ratings of BSs’ prestige take into account schools’ research reputations (Armstrong, 1995; Armstrong & Sperry, 1994), which as discussed previously, are based heavily on theory-oriented research. Research productivity can serve an important signaling function. It can provide a concrete indicator about a business school’s status, especially when there is imperfect information about its overall capabilities (Besancenot, Faria, & Vranceanu, 2008).

Mounting Faculty Shortage

One of the most challenging forces affecting BSs is a severe shortage of faculty, especially those holding doctoral degrees (Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business [AACSB] International, 2008a). BSs are producing far fewer PhDs than they did a decade ago, and a good number of them are finding more attractive alternatives to working in a business school (AACSB International, 2002, 2003; Zimmerman, 2001). Among the large contingent of scholars that comprised the first wave of PhDs employed in BSs during the 1960s and 1970s is a growing number of faculty who are choosing to retire or work part-time. Both of these trends are projected to accelerate in the coming years (AACSB International, 2008a). As shown in Figure 18.1, this mounting faculty shortage is resulting in BSs employing more discipline-based faculty and giving faculty greater power.

More discipline-based faculty

To address the faculty shortage, BSs are increasingly hiring from the disciplines of economics, psychology, and sociology (Pfeffer & Fong, 2002). The knowledge base and research methods of these social sciences are closely aligned to the management field. Moreover, for many of these scholars, the job prospects are far better in BSs than in disciplinary departments.

The growth of discipline-based faculty contributes to management research becoming more theory oriented. These scholars reinforce the long-held belief in BSs that this kind of research is the path to academic legitimacy. They promote research that is theory driven and methodologically sophisticated, which has become the standard for publication in top management journals (Pfeffer & Fong, 2002). This disciplinary focus is also finding its way into the training of doctoral students in BSs. Students in top programs increasingly supplement their business education with a minor or major in one of the disciplines. Faculty hiring decisions are more and more based on these PhDs having disciplinary knowledge and skills, which helps to assure that future management research will continue to be theory oriented.

Greater power to faculty

The growing faculty shortage is also giving faculty more power in BSs. This shift is especially the case for faculty publishing in top academic journals. They are the primary source of a school’s research reputation. Because they are in short supply, they can command high salaries and research support as well as reduced teaching loads. These researchers’ growing power is contributing in part to the two-tier faculty system described earlier. It affords them freedom to do research without being over-burdened with teaching and student demands. Their enhanced power also influences key decisions about faculty hiring, promotion and tenure, and rewards, all of which favor the kind of theory-oriented research at which these scholars excel.

Entrenched Values of Research Universities

Business schools have had an uneasy relation with the research universities that house them (Starkey & Tiratsoo, 2007). Periodically, they have faced university concerns about student quality, curriculum rigor, resource allocations, financial contributions to overhead, and the like. The most persistent and possibly critical issue, however, centers on questions of academic legitimacy. From BSs’ inception on university campuses, they have encountered skepticism from many disciplinary departments about the quality of their faculty and research. They have been accused of being little more than vocational schools closely aligned with the interests of big business.

Because these negative and partly erroneous perceptions can adversely affect BSs’ access to resources and autonomy to make decisions, BSs have worked hard to remedy them. This can be seen in the strides BSs have taken to adhere to the values of research universities. These ideals promote scientific rigor as the path to knowledge, generally through disciplinary research that is theoretically and methodologically sound (Pfeffer & Fong, 2002; Starkey & Tiratsoo, 2007). These values are deeply embedded in university practices and behaviors. As shown in Figure 18.1, they are reflected in university reward systems, which are closely tied to top-tier academic publications, a visible measure of research rigor. BSs have followed suit linking such publications to pay increases, promotion and tenure, endowed chairs, and research support. This reward system sends a powerful message to faculty that theory-oriented research, which is the primary path to top-tier publication, is valued and rewarded.

In summary, we have analyzed five important factors affecting BSs and shown how they set off a chain of events that influence faculty research. They create conditions within BSs that heavily favor theory-oriented research. When taken together, the forces create almost a “perfect storm” to thwart the kind of action-oriented research addressed in this book.

Enablers to Research Useful for Theory and Practice

Overcoming these barriers to action-oriented research is challenging, to say the least. The forces affecting BSs and the resulting chain of events are likely to persist, if not heighten, in the coming years. To address these barriers to more action-oriented research, BSs can (1) professionalize their research focus, (2) broaden their reward and career practices, and (3) enhance their engagement with practitioners.

Professionalize Research Focus

As discussed previously, BSs have sought legitimacy and prestige by emulating the theories and methods of discipline-based departments, thus doing more and more theory-oriented research. Although to some extent this emphasis has produced the intended effect, it also has led to a growing disconnect between BSs’ research and the management profession it intends to inform, as many critics have pointed out (e.g., Bennis & O’Toole, 2005; Ford et al., 2005; Pfeffer & Fong, 2002; Porter & McKibbin, 1988; Rynes, Bartunek, & Daft, 2001). One promising solution is for BSs to become more like other university-based professional schools such as medicine and law (Pfeffer & Fong, 2004; Sherman, 2009; Trank & Rynes, 2003). Research would be aimed at creating knowledge relevant to the management profession; it would provide a scientific basis for professional learning and practice (Lorsch, 2009; Pfeffer, 2009; see Chapter 9, On Knowing and Doing, this book).

This proposed shift toward “profession-oriented” research fits well with BSs’ competence in creating scientific knowledge. It brings that research expertise to bear on important issues of ongoing relevance to management, thus giving BSs a competitive advantage over other providers of management education and knowledge, such as consulting firms and schools that focus on teaching. Profession-oriented research can help to differentiate science-based management education from training and storytelling (AACSB International, 2008b). Its rigorous theorizing and empirical testing stand in stark contrast to the unsubstantiated claims and hyping that are so prevalent in nonacademic sources of management knowledge. It provides the evidence-based knowledge needed to guide wise management practice (Pfeffer & Sutton, 2006, 2007; Rousseau & McCarthy, 2007; see Chapter 14, Sticky Findings, this book).

Profession-oriented research can promote greater tolerance and appreciation for diverse theoretical and methodological approaches to creating management knowledge. Because it focuses research on a common domain or subject matter, no particular discipline, theory, or method is privileged over others. What matters is the quality of the research (rigor) and its contribution to understanding the phenomenon in question (relevance) (Pettigrew, 2001). The management domain is diffuse, complex, and changing; consequently the greater the variety of research approaches, the better are the chances of comprehending it. BSs could enable this diversity by providing a broad umbrella under which different forms of inquiry prosper and productively interact (Starkey, Hatchuel, & Tempest, 2004). They could create a supportive milieu for both basic research and more applied forms of inquiry. Moreover, they could promote useful exchanges and collaboration among researchers from different perspectives, all focused on gaining a shared understanding of the management domain.

Broaden Reward and Career Practices

Rewards are powerful determinants of behavior, even in scholarly settings like BSs. As discussed earlier, BSs have tended to reward top-tier academic publishing, which reinforces theory-oriented research. Although action-oriented research can lead to high-level publication, it generally takes longer, is messier and more difficult to conduct, and has a higher level of publication uncertainty than theory-oriented research (Van de Ven & Johnson, 2006). If BSs want both types of research to inform management knowledge, which is essential in my view, they must expand their reward practices to account for these features (AACSB International, 2008b; Starkey & Madan, 2001; Tushman & O’Reilly, 2007). One reasonable solution is to design two parallel reward systems, one geared to theory-oriented research and the other to action-oriented inquiry. Each would have its own performance measures, assessment cycle, and reward pool, though some overlap between the two systems seems sensible. The theory-oriented reward system is pretty much in place at most BSs, whereas the action-oriented system would need to be designed from scratch. This system would require developing measures of research impact that go beyond simple counts of journal quality, citations, and the like; perhaps metrics tied to effects on practice (AACSB International, 2008b). The assessment-reward cycle would probably need to be extended beyond the typical calendar year to account for the longer time it takes to do this research and to assess its consequences. Clearly, there are numerous practical challenges to measuring and rewarding action-oriented research. BSs might start by borrowing from the reward practices of those academic departments where long-term field research is more the norm, such as anthropology, political science, and sociology.

Consistent with these changes in reward practices, BSs can expand how they view faculty careers to support both theory- and action-oriented researchers (Ashford in Walsh et al., 2007). Currently, the careers of tenure-track faculty are seen pretty much within a context that presumes that theory-oriented research will be the norm throughout a career. At research universities, this assumption makes sense during faculty’s early career stages, when tenure and promotion are likely to depend on publishing in top-tier academic journals. It is questionable, however, during later career stages for those faculty members doing action-oriented research. They require career practices that value and support long-term engagement with practitioners around messy management issues. To support these scholars, BSs can be more flexible in how they structure and support faculty careers, perhaps creating different career tracks for theory and action researchers, like the dual reward systems suggested above. In early career stages, even though most faculty members would be on a theory-oriented career track, BSs could create small opportunities for engaging with practice for those wanting to develop in this direction. In later career stages, faculty continuing to do theory-oriented research would stay on that track much like they do today, while action researchers would move to a career track more consistent with their research. This career track would focus outward toward organizations and management rather than inward toward disciplines and other academics. It would include a combination of research, teaching, and service that emphasizes practice (see Chapter 6, Rigor and Relevance in Organizational Research). This dual career system would be flexible so faculty members could move between tracks depending on their changing interests and capabilities.

Enhance Engagement with Practitioners

To create useful knowledge, the quality of the relationship between researchers and practitioners can be as important as the content of the research itself. BSs can create mechanisms for facilitating faculty engagement with practitioners. These enable the two sides to explore opportunities for joint learning and research. They increase the chances that researchers will study important issues facing management, and that practitioners will learn the right lessons from the results and how to apply them. BSs are developing a variety of ways to relate to the practitioner community (Starkey & Madan, 2001). We describe approaches that seem particularly relevant to action-oriented research in the following sections.

Action-learning executive education workshops

These workshops evolved from traditional executive education programs (Tushman & O’Reilly, 2007; Tushman in Walsh et al., 2007; see Chapter 9, On Knowing and Doing, this book). They are a response to the common plea from participants for a closer connection between the academic content presented and the problems they face at work. To better link knowing with doing, the workshops tailor content to a specific firm, which sends teams of senior executives to campus for a few days. About half the time is spent in content sessions, and the other half in teams applying the content to company issues. Faculty design and deliver the content and facilitate the team sessions.

These action-learning workshops can help practitioners better understand and apply research to real problems. They can provide researchers with closer access to firms and better understanding of the important problems they are facing. These benefits in turn can lead to innovations in management practice and research that address key management issues and provides actionable results. To achieve these outcomes, researchers’ and practitioners’ roles, relationships, and expectations need to be explicit and well defined; each side must appreciate the other’s views and goals (Kimberly in Walsh et al., 2007).

Joint interpretive forums

BSs can bring together researchers and practitioners to discuss and reflect on particular issues or information. Joint interpretive forums generally are organized around a particular research project, management issue, or common topic (Mohrman, Gibson, & Mohrman, 2001). They can last from a few hours to a couple of days, and can recur periodically or be one-shot events. These face-to-face forums are highly interactive and can facilitate perspective taking and collective learning among participants, which in turn can broaden researchers’ and practitioners’ thought-worlds and appreciation for each other’s perspectives. Depending on the forum’s purpose and design, participants may jointly interpret research results, explore their relevance to practice, identify emerging areas for management inquiry, and make preliminary plans for action-oriented research projects.

Research suggests that joint interpretive forums are especially effective in helping participants conceptually understand the usefulness of research findings (Ginsburg et al., 2007; Mohrman, Gibson, & Mohrman, 2001). To assure that the results are subsequently implemented, however, “perspective taking” must occur between researchers and practitioners. This means that each side must recognize and understand the other’s values, meanings, and beliefs. This type of understanding enables a researcher to translate research results into a practitioner’s meaning system and organizational context.

Knowledge networks

These link BSs and companies into an interactive partnership that seeks to align research with practice (see Chapter 4, A Ten-Year Journey of Cooperation; and Chapter 13, Professional Associations). The network provides a collaborative structure for researchers and practitioners to determine a research agenda that captures both of their interests, to design and fund promising research projects, and to apply the findings. One of the oldest and most successful knowledge networks is the Marketing Science Institute (MSI) currently headquartered in Cambridge, Massachusetts (Starbuck in Walsh et al., 2007). Founded in 1961 by Wharton’s dean, it aims to bridge the gap between marketing research and practice. Today, MSI connects executives from around 70 global firms with researchers from over 100 BSs worldwide. MSI identifies research priorities through member polling and global discussions. It then circulates them to researchers who submit research proposals; about 35 projects are funded each year. Research results written in practical language are disseminated promptly to members. MSI has its own publication series and routinely holds and co-sponsors a variety of conferences and workshops to discuss research findings, explore how to implement them, and encourage applied research. These events are highly interactive and facilitate meaningful dialogue between researchers and practitioners. Research sponsored by MSI often appears in top academic journals and wins prominent awards.

Executive doctoral programs

These alternative doctoral programs are aimed at working professionals with extensive practical experience (Hart et al., 2004; Hay, 2004). They generally offer a blend of practice, theory, and research in a format that enables students to work full-time while pursuing their studies. Executive doctoral programs are not intended to educate academic researchers but scholar-practitioners who can serve as boundary spanners linking the worlds of academe and business (see Chapter 11, Integrating Theory to Inform Practice). Graduates typically continue to work in business or government, enter management consulting, or seek employment in BSs as clinical or adjunct faculty.

Executive doctoral programs are growing in number and size (Bisoux, 2009). Although they are relatively new in business education, they can offer new and potentially valuable ways to engage with practitioners. Graduates of these programs are likely to be strong proponents of evidence-based management, and they can extend that perspective to the organizations in which they work or consult. They can encourage leaders to ask hard questions about the efficacy of different management innovations; they can show them how to measure and assess the consequences of their decisions. Graduates can play an important role in disseminating research findings to practitioners. They can use their dual perspective to translate research results so practitioners can understand and use them, something academic researchers typically are unwilling or unable to do. Graduates of these programs can help BSs deal with the growing shortage of faculty with doctoral degrees. They can bring their academic and business expertise into the classroom to help students tie theory to practice. They can facilitate collaborative research between academics and practitioners to create useful knowledge.

Because executive doctoral programs are so new to business education, there is little information on which to judge their effectiveness in preparing students to be scholar-practitioners. Few of the programs are housed in research-based BSs, and there is likely wide variation in the quality of their students and curriculum. To their credit, a growing number of these doctoral programs are working diligently to develop and legitimize their role in management education. They encourage their students to participate regularly in professional conferences such as the Academy of Management; their administrators and faculty meet periodically with their counterparts in other programs to share problems and solutions and to develop a common set of professional practices.

Business school research centers

These provide a formal structure for connecting BSs to the practitioner community (see Chapter 1, Research for Theory and Practice). Research centers generally are organized around a domain that fits a particular constituency within industry, such as human resources, marketing, finance, and the like. Emphasizing a particular domain provides them with identifiable and potentially receptive partners for sharing knowledge, gaining access to firms, and sponsoring research and related activities. Research centers serve as a hub for academics and practitioners, periodically bringing them together to discuss research knowledge and its practical applications, to identify key emergent problems, and to facilitate networking among practitioners so they can share their experiences and learn from one another. Research centers may have their own professional staff that conducts action-oriented research and generates useful knowledge, such as the Center for Effective Organizations at the Marshall School of Business, University of Southern California; or more commonly, they may be a virtual organization that draws on the research of business school faculty and links it to the practitioner community.

Research centers are a particularly effective way for BSs to engage with practitioners. They have a distinct identity, an applied research competence, a specific practitioner base, and ongoing relationships with it. Because they have a foot in both academic and practitioner worlds, research centers know the values, beliefs, and practices of each of them and can serve as boundary spanners linking them together. They can help explicate the expectations, roles, and rules that facilitate effective research partnerships between the two sides (Hatchuel, 2001).

Research centers can have problems sustaining these efforts, however, especially if they are run with professional researchers and support staff that must be funded and managed. Centers may receive deficient funding, support, and direction from BSs; they can easily become disconnected from them and treated as stand-alone appendages that operate and survive by their own wits and funding. Research centers are prone to external jolts that adversely affect their industry partners, such as the recent global recession. The demands of academe and practice are difficult to jointly satisfy, and being seen as marginal in both worlds can be stressful. Add to this the constant pressure to generate rigorous and relevant knowledge, to publish the results in respectable academic and applied outlets, to gain funding and balance a budget, and to keep all of this organized and moving forward can be daunting even to the most skilled and ardent researchers.

BSs need to address these problems strategically as a key part of an overall plan for connecting to the external world. They need to determine the unique role that research centers will play in this strategy and how they will fit with other linking mechanisms, such as student recruiting, job placement, and fund-raising. These strategic choices are essential for addressing how research centers should be funded, organized, assessed, and rewarded. They provide a context for dealing with many of the problems that research centers face. When treated strategically and provided with sufficient funds, support, and direction, research centers can be a valuable resource for satisfying the dual demands for rigor and relevance in management knowledge; they can be a powerful bridge between the academic and business communities.

Conclusion

In writing this chapter, I gained a better appreciation for the complex challenges that BSs face today and the difficulties they pose for creating knowledge that is both rigorous and relevant, the joint demands that all professional schools must satisfy. Clearly, BSs have come down on the side of rigor for the reasons identified in this chapter, and this emphasis is being reinforced through existing norms, practices, and beliefs. The enablers I described for remedying this imbalance seem promising yet face an uphill battle to overcome these inertial forces. Changing the status quo for how knowledge is created in BSs is an extremely difficult, if not impossible, task. Yet, we must meet the challenge if we truly want to create knowledge that is useful for theory and practice.

REFERENCES

AACSB International. (2002). Management education at risk. Report of the Management Education Task Force to the AACSB International Board of Directors. Tampa, FL: AACSB International.

AACSB International. (2003). Sustaining scholarship in business schools. Report of the Doctoral Faculty Commission to the AACSB International Board of Directors. Tampa, FL: AACSB International.

AACSB International. (2008a). Business school faculty trends 2008 report. Tampa, FL: AACSB International.

AACSB International. (2008b). Final report of the AACSB international impact of research task force. Tampa, FL: AACSB International.

Adler, N., Shani, A., & Styhre, A. (Eds.) (2004). Collaborative research in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Argyris, C., Putnam, R., & Smith, D. (1985). Action science: Concepts, methods and skills for research and intervention. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Armstrong, J. S. (1995). The devil’s advocate responds to an MBA student’s claim that research harms learning. Journal of Marketing, 59, 101–106.

Armstrong, J. S., & Sperry, T. (1994). The ombudsman: Business school prestige—research versus teaching. Interfaces, 24(2), 13–22.

Beauvais, P. (2007). The fifth freedom: Access to postsecondary education in America today. American Academic, 3(1), 1–7.

Becker, E., Lindsat, C., & Grizzle, G. (2003). The derived demand for faculty research. Managerial and Decision Economics, 24(8), 549–567.

Bennis, W., & O’Toole, J. (2005). How business schools lost their way. Harvard Business Review, 83, 96–104.

Besancenot, D., Faria, J., & Vranceanu, R. (2008). Why business schools do so much research: A signaling explanation. ESSEC École Supérieure des Sciences Économiques et Commerciales Research Centre, Cergy-Pontoise, France.

Bisoux, T. (2009, March–April). Solving the doctoral dilemma. BizEd, 24–31.

Corley, K., & Gioia, D. (2000). The rankings game: Managing business school reputation. Corporate Reputation Review, 3(4), 319–333.

DeAngelo, H., DeAngelo, L., & Zimmerman, J. (2005). What’s really wrong with U.S. business schools? Los Angeles: Marshall School of Business, University of Southern California.

Fee, C., Hadlock, C., & Pierce, J. (2005). Business school rankings and business school deans: A study of nonprofit governance. Financial Management, 34(1), 143–166.

Ford, E., Duncan, W. J., Bedeian, A., Gintei, P., Rousculp, M., & Adams, A. (2005). Mitigating risks, visible hands, inevitable disasters, and soft variables: Management research that matters to managers. Academy of Management Executive, 19(4), 24–38.

Ginsburg, L., Lewis, S., Zackheim, L., & Casebeer, A. (2007). Revisiting interaction in knowledge translation. Implementation Science, 2(34), 1–11.

Gordon, R., & Howell, J. (1959). Higher education for business. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hambrick, D. (1994). 1993 Presidential Address: What if the Academy actually mattered? Academy of Management Review, 19, 11–16.

Hart, H., Kylen, S., Norrgren, F., and Stymne, B. (2004). Collaborative research through an executive Ph.D. program. In N. Adler, A. Shani, & A. Styhre (Eds.), Collaborative research in organizations (pp. 101–116). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hatchuel, A. (2001). The two pillars of new management research. British Journal of Management, 12 (Special Issue), S33–S39.

Hay, G. (2004). Executive Ph.D.s as a solution to the perceived relevance gap between theory and practice: A framework of theory-practice linkages for the study of the executive doctoral scholar-practitioner. International Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 7(2), 375–393.

Huff, A. (2000). 1999 Presidential Address: Changes in organizational knowledge production. Academy of Management Review, 25(2), 288–293.

Khurana, R. (2007). From higher aims to hired hands. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues, 2(4), 34–46.

Lorsch, J. (2009). Regaining lost relevance. Journal of Management Inquiry, 18, 108–117.

Mintzberg, H. (2004). Managers not MBAs: A hard look at the soft practice of managing and management development. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Mohrman, S., Gibson, C., & Mohrman, A. (2001). Doing research that is useful for practice: A model and empirical exploration. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 357–375.

Pettigrew, A. (2001). Management research after modernism. British Journal of Management, 12 (Special Issue), S61–S70.

Pfeffer, J. (2009). Renaissance and renewal in management studies: Relevance regained. European Management Review, 6(3), 141–148.

Pfeffer, J., & Fong, C. (2002). The end of business schools? Less success than meets the eye. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 1(1), 78–95.

Pfeffer, J., & Fong, C. (2004). The business school ‘business’: Some lessons from the US experience. Journal of Management Studies, 41(8), 1501–1520.

Pfeffer, J., & Sutton, R. (2006). Profiting from evidence-based management. Strategy & Leadership, 34(2), 35–42.

Pfeffer, J., & Sutton, R. (2007). Suppose we took evidence-based management seriously: Implications for reading and writing management. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 6(1), 153–155.

Porter, L., & McKibbin, L. (1988). Management education and development. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Rousseau, D., & McCarthy, S. (2007). Evidence-based management: Educating managers from an evidence-based perspective. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 6, 94–101.

Rynes, S., Bartunek, J., & Daft, R. (2001). Across the great divide: Knowledge creation and transfer between practitioners and academics. Academy of Management Journal, 44(2), 340–355.

Rynes, S., & Trank, C. (1999). Behavioral science in the business school curriculum: Teaching in a changing institutional environment. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 808–824.

Sherman, H. (2009). Improving the relevance of university business schools: Refocusing on providing professional business education. American Journal of Business, 24(1), 3–6.

Sonnenberg, W. (2004). Federal support for education: Fiscal years 1980–2003. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (NCES 2004-026)

Starkey, K., Hatchuel, A., & Tempest, S. (2004). Rethinking the business school. Journal of Management Studies, 41(8), 1521–1531.

Starkey, K., & Madan, P. (2001). Bridging the relevance gap: Aligning stakeholders in the future of management research. British Journal of Management, 12(Special Issue), S3–S26.

Starkey, K., & Tiratsoo, N. (2007). The business school and the bottom line. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Trank, C., & Rynes, S. (2003). Who moved our cheese? Reclaiming professionalism in business education. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 2(2), 189–205.

Tushman, M., & O’Reilly, C. (2007). Research and relevance: Implications of Pasteur’s quadrant for doctoral programs and faculty development. Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 769–774.

Van de Ven, A., & Johnson, P. (2006). Knowledge for theory and practice. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 802–821.

Walsh, J., Tushman, M., Kimberly, J., Starbuck, B., & Ashford, S. (2007). On the relationship between research and practice. Journal of Management Inquiry, 16(2), 128–154.

Zimmerman, J. (2001). Can American business schools survive? (Financial Research and Policy Working Paper No. FR 01-16). The Bradley Policy Research Center, University of Rochester, New York.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Thomas G. Cummings is a leading international scholar and consultant on strategic change and designing high-performance organizations. He is Professor and Chair of the Department of Management and Organization at the Marshall School of Business, University of Southern California. He has authored over 70 articles and 22 books. Dr. Cummings was formerly President of the Western Academy of Management, Chair of the Organization Development and Change Division of the Academy of Management, and Founding Editor of the Journal of Management Inquiry. He was the 61st President of the Academy of Management, the largest professional association of management scholars in the world with a total membership of over 19,000.