Barriers Impeding Access to Higher Education

The Effects of Government Education Policy for Disadvantaged Palestinian Arab and Jewish Citizens

Khalid Arar1, Kussai Haj-Yehia2 and Amer Badarneh3, 1The Center for Academic Studies and Sakhnin College for Teacher Education, Jaljulya, Israel, 2Beit-Berl Academic College, Taybe, Israel, 3Sakhnin Academic College, Sakhnin, Israel

This chapter discusses Israeli policy concerning access to higher education (HE) and points out barriers impeding access for the Palestinian Arab minority and Jewish peripheral disadvantaged groups. Relying on meta-analysis of documents and other resources describing policies and trends in HE in Israel and their implications for underprivileged groups, the chapter attempts to answer the following questions: (i) How has Israeli government policy regarding access to HE for underprivileged groups, and in particular for the Palestinian Arab minority, changed since the establishment of the state? And (ii) what are the blocks encountered by peripheral and minority groups in their attempt to access HE in Israel? Findings show that despite increasing numbers and percentages of disadvantaged groups in Israeli HE (especially Palestinian Arab students) studying in HE institutions, structural blocks have continued to hinder their access to this important resource. This has led students from peripheral groups who encountered obstacles in entry to Israeli HE to seek new alternatives, such as studying abroad. This chapter contributes to an understanding of the process of development of Israeli policies concerning HE for disadvantaged populations. Its findings may have international significance since similar difficulties are encountered in access to HE among underprivileged or peripheral populations in other world states.

Keywords

Palestinian Arab minority; access to higher education; disadvantaged groups; higher education policy

Introduction

Education and especially higher education (HE) shapes the socio-economic future of a society and can help bridge gaps between underprivileged and established populations (Altbach, 2011; Leonard & Rab, 2010; Shiner & Modood, 2002; Unterhalter & Carpentier, 2010). Consequently, access to HE becomes an issue of particular significance for minority and peripheral groups, disadvantaged by their low socio-economic status, lack of privilege, geographical isolation, or discrimination in a particular state (Al-Haj, 2003; Altbach, Reisberg, & Rumbley, 2010; Arar et al., 2015).

Israel’s HE system was initially developed as part of a nation-building policy even before the establishment of the State (Volansky, 2005). The indigenous Palestinian population was not explicitly envisaged as an integral part of this policy, and their desire to create their own separate university met with resistance (Abu El-Hija, 2005). The integration of Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel (PAI) within national institutions has often been seen as problematic and structural blocks have restricted the acceptance of this minority group and other peripheral populations into HEI, as part of an elitist ethos (Arar & Haj-Yehia, 2010; Gamliel & Cahan, 2004).

This chapter offers meta-analysis of Israeli policies concerning access to HE for the PAI and other peripheral groups over time. More specifically, we attempt to characterize policies and trends in HE in Israel with regard to underprivileged groups according to the following questions:

1. How has Israeli government policy regarding access to HE for underprivileged groups, and in particular for the PAI, changed since the establishment of the state?

2. What are the blocks encountered by peripheral and minority groups in their attempt to access HE in Israel?

The chapter begins by describing the methodology used for this research. Using this methodology it then describes the research context in the State of Israel, tracing the development of the different components of the HE system and admission criteria. It describes challenges facing the Palestinian minority and other peripheral groups in Israel when attempting to access higher education and the challenges involved in constructing equity of access. The chapter ends with certain conclusions for HE policy in Israel.

Methodology

One of the acknowledged weaknesses of research concerning access policies of Higher Education Institutions (HEI) and their influence on minority and socio-economically disadvantaged groups is the lack of longitudinal data (Croll, 2009). This chapter offers a comprehensive overview of Israel’s HEI policies over time based on meta-analysis of official statistics and other official documents, and conclusions of relevant recent quantitative and qualitative research studies by the authors and others. Conclusions reached from this analysis describe the context in the State of Israel and trace the development of the different components of the Israeli HE system and the challenges faced by the PAI minority and other peripheral groups in attaining access to HEI in Israel.

The Context—Higher Education in the State of Israel

The State of Israel was established in 1948, and defined as the Jewish homeland. The Palestinian Arab population remaining within Israel’s borders numbered a mere 1,56,000, weakened and depleted by war and the loss of its elite due to expulsion or flight. The Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel (PAI) are a unique national minority, because this is a former majority that became a minority in its own land overnight (Morris, 1991). Sixty years later this indigenous ethnic minority has multiplied ten times and according to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS, 2014), numbered 1,694,000 persons in 2013, representing 20.7% of the country’s population (composed of 82.1% Muslims, 9.4% Christians and 8.4% Druze).

PAI contend with a constant identity conflict as citizens of a state that is officially defined as a Jewish state and not a state for all its citizens (Rouhana, 1997). Most PAI identify themselves as Palestinians and part of the Arab nation yet they are citizens of a country that is in conflict with members of its own people, the Palestinian people in neighboring states and with the Arab nation (Nakhleh, 1979).

Despite being the state’s largest minority, (CBS, 2014), the PAI endure discriminatory government policies resulting in deprivation in almost all domains (Suleiman, 2002). Additionally, the Jewish majority population is also diversified ethnically, religiously, and culturally. These differences are often reflected in different degrees of socio-economic integration (Iram, 2011).

The Significance of HE for Peripheral Groups in Israel

Minorities and peripheral populations identify Higher Education Institutions (HEI) as an important asset, helping them to acquire vocational qualifications and political skills and improve their socio-economic status (Brooks & Waters, 2011; Shiner & Modood, 2002). As a result, they are willing to invest intensive effort to gain access to HEI (Altbach, 2011). Two main factors have been shown to influence the student’s ability to gain access to HEI: (i) the student’s demographic background, and (ii) the HEI’s selection policy and admission requirements (Altbach et al., 2010; Arar & Mustafa, 2011).

Education in Israel is segregated, with separate systems for religious and secular Jewish children and for Arab children. Each system includes both state and nonstate schools. The language of studies for Jewish children is Hebrew, and for Arab children, Arabic. Because of the segregation, the likelihood of encounters between Jewish and Arab children is very low (Gibton, 2011; Golan-Agnon, 2006). Yet, significant gaps were still found between the lower achievements of Arab schools and higher achievements of Jewish schools in all subjects, in all classes, and in every year.

These gaps have significant consequences for PAI students aspiring to gain access to Israel’s HEI, and they reflect the disadvantaged status of most Arab school education. Table 6.1 illustrates differences in numbers and percentages between Arab and Jewish students at all stages of HE.

Table 6.1

Students studying for academic degrees in HEI institutions in Israel, 2011–2012

| Students at universities | Students at academic colleges | Students in education colleges | Total | |

| 1st Degree | ||||

| Absolute numbers | 74,923 | 87,409 | 26,908 | 189,240 |

| Female students | 54.5% | 49.7% | 80.3% | 55.9% |

| Population Groups | ||||

| Jews and others | 86.4% | 93.6% | 73.7% | 87.9% |

| Jews | 83% | 90.1% | 72.7% | 84.8% |

| Arabs | 13.6% | 6.4% | 26.3% | 12.1% |

| 2nd Degree | ||||

| Absolute numbers | 50,759 | 9318 | 3101 | 63,178 |

| Female students | 57.7% | 58.3% | 80.7% | 59.2% |

| Population Groups | ||||

| Jews and others | 92.3% | 94.2% | 78.6% | 91.8% |

| Jews | 90.2% | 92.7% | 78% | 89.9% |

| Arabs | 7.7% | 5.8% | 21.4% | 8.2% |

| PhD | ||||

| Absolute numbers | 10,590 | 10,590 | ||

| Female students | 52.4% | 52.4% | ||

| Population Groups | ||||

| Jews and others | 95.6% | 95.6% | ||

| Jews | 93.2% | 93.2% | ||

| Arabs | 4.4% | 4.4% | ||

Source: CBS (2013).

The reports of the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS, 2013) indicate that only approximately 16% of all PAI students studying for their first degrees in Israel’s universities came from communities graded in the lower socio-economic clusters (clusters 1–4). Approximately 35% of Arab and Jews studying for a first degree on the main campuses of Israel’s universities come from localities situated in the top socio-economic clusters (7–10), including mixed Arab–Jewish towns (see Table 6.2 below). These data seems to indicate that HE in Israel’s universities remains a privilege for those with greater financial resources.

Table 6.2

High school graduates from 2002, which began their studies in Israeli HEI before 2010, by type of high school studies, socio-economic cluster of community, percentages of all the high school graduates in each category

| Characteristics | % |

| Total high school graduates who began studies in universities | 33.8 |

| % of Jewish Education System graduates who began studies in universities | 36.4 |

| Graduates from theoretical stream | 44.9 |

| Graduates from technological stream | 27.4 |

| Live in community in socio-economic clusters 1–4 | 23.6 |

| Live in community in socio-economic clusters 5–7 | 34.9 |

| Live in community in socio-economic clusters 8–10 | 47.6 |

| % of Arab Education System graduates who began studies in universities | 18.2 |

| Graduates from theoretical stream | 20.8 |

| Graduates technological stream | 15.3 |

| Live in community in socio-economic clusters 1–4 | 16.5 |

| Live in community in socio-economic clusters 5–7 | 20.4 |

| Live in community in socio-economic clusters 8–10 | 29.3 |

Source: CBS (2012), Table no. 62.

HE Expansion in Israel

Altbach et al. (2010) identified three basic stages in contemporary HE development: elitism, massification, and universal access. Almost all countries, including Israel, have dramatically increased their HE participation rates (Hemsley-Brown, 2012; Kirsh, 2010). The Israeli state participates in approximately 50.6% of the funding for HEIs. Its declared goal is to broaden access to HE as an important step in integrating different sectors of the population into the labor market, investing in the development of human capital and building a knowledge-intensive economy (Kirsh, 2010).

From the early nineties, three major structural reforms effected changes in the HEI system in response to growing demand for HE (Yogev & Ayalon, 2008):

1. Diversification—autonomous regional and technological colleges were established, funded by the CHE, but not for research. Teacher education colleges were also upgraded to become academic colleges granting academic degrees. By the year 2000, the number of public colleges had increased three times.

2. Privatization—From 1994 the CHE permitted private colleges to operate and grant academic degrees under CHE regulation but without public funding. The number of accredited HEI in Israel rose from 23 in 1993 to 66 in 2011, while the number of students increased from 118,000 in 1993 to 290,000 in 2009. These trends significantly improved the access of marginal groups such as the PAI to HE (Arar & Mustafa, 2011).

3. Internationalization—In 1994, the government decided to allow the establishment of annexes of foreign universities in Israel (Volansky, 2012).

By 2012, there were 68 HEI recognized by the CHE to grant academic degrees (9 universities, 20 public academic colleges, 16 private academic colleges and 23 academic colleges of teacher education) (Iram, 2011; Volansky, 2012).

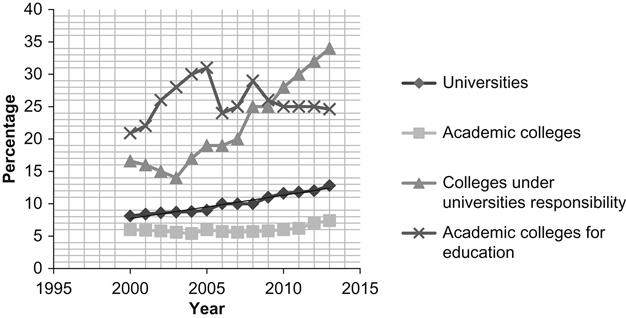

Despite the government’s declared policy of strengthening HE in peripheral regions, 38.5% of the HEI are located in the central urban region. This is despite a rise in population of 31% in the peripheral regions. This uneven geographical distribution of HEI, leads also to paucity of courses available in peripheral areas so that its residents often have to study far from home (Kirsh, 2010). The trends of diversification, privatization, and internationalization of HEI were not specifically tailored to accommodate PAI needs for access and development. The CHE continued to restrict the establishment of Arab HEI (Arar & Mustafa, 2011). Figure 6.1 below represents the distribution of PAI students studying 1st degrees in the different types of Israeli HEI from 2000 to 2013.

In 2012, 29,240 Arab students studied for all levels of academic studies in Israel’s HEI. An additional 5210 Arab students studied in the Open University. Of the Arab students studying in the universities, academic colleges, and academic colleges of education, 23,065 studied for first degrees, 4895 for second degrees. 510 studied for a doctorate and 230 undertook certificate studies (Haj-Yehia & Arar, 2014). An increase was noted in the proportion of PAI students among all Israeli first degree students rising to 13% in 2012. A substantial part of this increase stemmed from the opening of colleges, in peripheral areas where there are concentrations of PAI population. In the academic year 2013, 36% of the PAI students in HEI studied for a first degree in the main university campuses, 23% in academic colleges of education, 19% in publicly funded academic colleges, 11% in annexes of major universities, and approximately 11% in privately funded colleges (ibid.).

The increase in total number of PAI academic students actually stems from several factors, three of them more prominent: (i) the increased rate of success in Matriculation examinations in Arab high schools, which rose from 22% in the mid-1990s to 38% at the beginning of the 21st century; (ii) a continuous increase in the proportion of PAI women studying in universities since the late 1980s (Arar & Mustafa, 2011); and (iii) the above-mentioned expansion of the HEI system. Having described the expansion of the Israeli HE system, the discussion now turns to changes in admissions policy and criteria for the different HEI.

Trends in HEI Admissions Policy and Criteria

Israel’s HEI mostly select first-degree students according to an aggregate computation of matriculation exams and psychometric entrance exams. In certain cases, an especially high result for one of these tools may exempt the candidate from the need to present results for the other tool. Public debate concerning the dubious value of the psychometric exam as an essential admission criterion for Israeli HEI, recently prompted a proposal for reform of senior high schools’ evaluation processes that will be implemented from the academic year 2014–2015, so that the matriculation certificate can serve as an entry certificate for HEI instead of psychometric testing (Weinenger & Stener, 2014). Since PAI students face many difficulties when they apply for acceptance to HEI in Israel, some have described their path to academia as a “Via Dolorosa.” Table 6.3 illustrates the underachievement and other obstacles impeding PAI candidates’ admission to Israeli universities in comparison to Jewish candidates and their actual rates of participation in Israel’s HEI.

Table 6.3

The “via dolorosa” to HE in Israel

| Jews | Arabs | |

| Percentage of total high school students | 72% | 28% |

| Percentage of ethnic group studying in Grade 12 | 95% | 65% |

| Percentage of ethnic group, who have access to matriculation exams | 78% | 60% |

| Percentage of ethnic group eligible for matriculation certificate | 55% | 31% |

| Percentage of ethnic group that meet the minimum requirements for university admission | 47% | 23% |

| Average psychometric testing score | 555 Points | 432 Points |

| Percentage of applicants rejected for admission to undergraduate courses | 17% | 30% |

| Percentage of University undergraduate students | 87.9% | 12.1% |

| Percentage of candidates from ethnic group rejected for MA studies | 67% | 41% |

| Percentage of all PhD students | 95.6% | 4.4% |

| Percentage of university faculty members | 97.3% | 2.7% |

| Percentage of members of the administrative staff at universities | 98.5% | 1.5% |

Following this review of HEI admission policies, the discussion now turns to review other challenges faced by PAI and other peripheral populations when applying to HEI.

Challenges to Access and Equity in Israel

Studies have shown that structural blocks are often set up to limit the access of weaker populations and minorities to HE institutes (Arar & Haj-Yehia, 2013; Shiner & Modood, 2002). PAI and other underprivileged strata of society still have a lower rate of acceptance to HEI than Jewish students do.

Arar and Mustafa (2011) found five structural blocks that obstruct access to Israel’s HEI for PAI students. While socio-economic gaps also disadvantage other weaker peripheral and marginal populations, there are some specific blocks, detailed below, which mainly hinder PAI applicants so that only 23% of PAI high school graduates met the entrance criteria for acceptance into academic institutes in 2011/2012; and only 9% of those who completed first-degree studies were PAI (Arar & Haj-Yehia, 2013).

The Pre-University Block

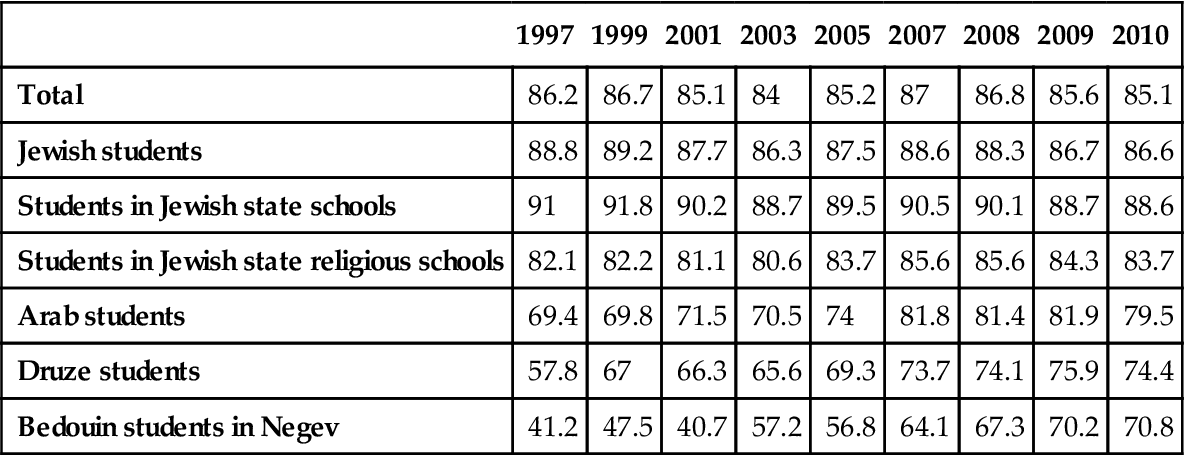

HEI admission requirements constitute the main block preventing PAI access to Israeli universities. The requirement for excellent matriculation results constitutes an initial stumbling block for PAI candidates, since they have low average results in comparison to Jewish students (Abu-Saad, 2006) (Table 6.4).

Table 6.4

Percentage of students qualifying for HEI admission out of total number of students eligible for a high school graduation certificate, selected groups, 1997–2010

| 1997 | 1999 | 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| Total | 86.2 | 86.7 | 85.1 | 84 | 85.2 | 87 | 86.8 | 85.6 | 85.1 |

| Jewish students | 88.8 | 89.2 | 87.7 | 86.3 | 87.5 | 88.6 | 88.3 | 86.7 | 86.6 |

| Students in Jewish state schools | 91 | 91.8 | 90.2 | 88.7 | 89.5 | 90.5 | 90.1 | 88.7 | 88.6 |

| Students in Jewish state religious schools | 82.1 | 82.2 | 81.1 | 80.6 | 83.7 | 85.6 | 85.6 | 84.3 | 83.7 |

| Arab students | 69.4 | 69.8 | 71.5 | 70.5 | 74 | 81.8 | 81.4 | 81.9 | 79.5 |

| Druze students | 57.8 | 67 | 66.3 | 65.6 | 69.3 | 73.7 | 74.1 | 75.9 | 74.4 |

| Bedouin students in Negev | 41.2 | 47.5 | 40.7 | 57.2 | 56.8 | 64.1 | 67.3 | 70.2 | 70.8 |

Source: Haj-Yehia & Arar (2014); CBS (2012).

Israel’s Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT)—Psychometric Testing

It is argued that psychometric tests discriminate against examinees from minority or underprivileged socio-cultural backgrounds (Abu-Saad, 2006; Yogev & Ayalon, 2008). Accordingly, PAI students achieve 123–126 points less (out of 800 maximum points) in psychometric testing results than Jewish Israeli students (Maagen & Shapira, 2009). Low psychometric results limit the acceptance of many PAI students to their preferred disciplines and they compromise by studying fields in which they have less interest (Arar & Mustafa, 2011).

Karletz, Bin-Simon, Ibrahim, and Avitar (2014) and other researchers argue that Arab students’ lower results in psychometric testing are due to significant differences in the efficient reading of texts in the two languages, Hebrew and Arabic. Thus the psychometric test in Arabic, constructed primarily on restricted time thinking, does not accurately reflect the PAI candidate’s potential to succeed in academic studies (ibid).

Minimum Age Limit

Some Israeli university faculties do not accept students under the age of 20. Most Jews complete compulsory military service at the age of 21, so the age threshold does not disadvantage them, however the requirement of a minimum age (20 years) for several majors prevents Arab and orthodox Jewish students (both of whom mostly do not serve in the army) from starting tertiary studies immediately after high school and matriculation exams. This is especially problematic for PAI women since they marry relatively young (20.2 years compared to 25.5 years among Jewish women) and usually give birth to many children (4.3 births per woman compared to 2.2 among Jewish women) (Gara, 2013). The minimum age regulation therefore increases the probability that they will start a family without ever gaining HE (Arar & Mustafa, 2011).

Language and Culture Barrier

Since the medium of instruction in Israeli universities is either Hebrew or English, PAI and also immigrants from Russia and Ethiopia are disadvantaged, especially in their fresher year, since these languages constitute their second or third languages. However, the major obstacle for PAI students, especially PAI women is the cultural barrier. Israeli university campuses expose PAI women to a mix of ethnic, national, and gender-related cultural norms that does not exist in their home communities. Research has shown that this experience can constitute a “culture shock” for some PAI women (Abu-Rabia-Queder & Arar, 2011).

PAI students often have a feeling of alienation in the Israeli campuses that are suffused with Western academic ideals and practices. In general academic contents develop the Zionist historical narrative, promoting the ideal prototype of the “New Jew,” while Israeli sociology has often studied the development of the PAI minority Israel in a distorted manner (Gur-Zeev, 2005), though post-Zionist research is beginning to show other perspectives on Israeli history and ideology.

Entrance Interviews

In addition to the above admission requirements, PAI and new immigrant Jewish students face linguistic and other difficulties in the personal interview required for admission to some prestigious disciplines. Interviews are conducted in Hebrew and do not consider differences in candidates’ language and culture, so that even though PAI students study Hebrew in school (starting in Grade 2 as their second language) candidates whose mother language is Hebrew have an advantage (Arar & Haj-Yehia, 2010; Golan, 2011). Together, these factors constitute a structural barrier that may exclude PAI and other peripheral students from Israeli academia.

Despite the recent increase in the number of PAI applicants accepted to universities, the average of PAI candidates, who are rejected, remains high—38.8% in 2009–2010 (Gara, 2013).

Overcoming Blocks and Achieving Equity in Access to HEI in Israel

The documentary analysis revealed four main categories of themes that help to answer the research questions relating to blocks encountered by minority, marginal, and peripheral groups aspiring to access HEI in Israel, and the strategies these populations employ to overcome these blocks.

Blocks Encountered by Students Seeking Access to HEI in Israel

Research in Israel and abroad has pointed up significant discrepancies in education availability and achievements between students with different demographic characteristics, between the state’s central and peripheral regions and between majority and minority groups (Ben-David, 2014a). These gaps deepen due to preferential distribution of government funding to schools in central regions rather than to peripheral regions, and to the Jewish school system rather than to the Arab school system (Arar & Abu-Asbah, 2013). Education budgets given to Arab local governments are 35% less in proportion to the PAI population than those given to Jewish local governments (Ben-David, 2014a). Results of PAI students in the international standard PISA exam were on average 116 points less than Jewish Israeli achievements (Arlosoroff, 2014). This differential is maintained in university entrance exams and in the underrepresentation of PAI and other peripheral students in HEI (Arar & Mustafa, 2011; Karletz et al., 2014).

Coping Strategies to Overcome Blocks

The students who are unable to pass the admission process to study their chosen discipline in HEI may choose one of three alternative paths:

1. An attempt to improve their potential to be admitted by taking a one year preparatory course in the chosen university enabling them to improve their grades or a “preparatory course for admission interviews.” Of course, these courses require material resources and support that families from lower socio-economic strata often cannot enlist.

2. Studies in a private HEI. These HEI often have lower admission requirements than the public universities and some do not condition admission on psychometric test results. These colleges charge twice the tuition fees of the universities or even more, so that this is only a relevant alternative for those with means. Table 6.2 above shows the distribution of students studying in HEI in Israel, by type of institute.

3. Studying in HEI abroad—Since many PAI face rejection by their preferred faculties in Israeli universities, some students compromise by studying less attractive disciplines with easier admission criteria, a path that often leads them to drop out. Rejected candidates and dropouts together constitute approximately 42% of all PAI university candidates. Often disappointed candidates turn to HEI abroad (Arar & Haj-Yehia, 2013; Haj-Yehia & Arar, 2009), despite the difficulties involved in migration to a foreign country. The former USSR universities were once a popular destination among PAI partly due to scholarships given by the Israeli Communist Party. After the collapse of the USSR, universities in Western Europe and former Communist countries have become more popular among PAI, especially Germany, Italy, Romania, and Moldova (Haj-Yehia, 2002; Haj Yehia & Arar, 2014).

Since the 1994 Israel-Jordan treaty, the number of PAI studying in Jordan has increased from 198 in 1998 to 5400 students today, including a relatively high proportion of women (in comparison to the gender distribution in PAI studies in other HE venues abroad) (Arar & Haj-Yehia, 2010). In 2011, the number of PAI studying abroad was estimated at 9260 students, the majority of them studying in Jordanian and Palestinian Authority universities (Arar & Haj-Yehia, 2013; Haj-Yehia & Arar, 2014; OECD, 2013). Most PAI went abroad to study prestigious majors such as Medicine, Pharmacy, and Para-medical disciplines, which they were unable to access in Israel. The phenomenon of PAI studying abroad exceeds the percentage of migrant students from other nation states (Brooks & Waters, 2011).

Figure 6.2 shows how the numbers of PAI students studying in HEI increases when those studying abroad are also taken into account.

Developing Policy Concerning the Barrier of Psychometric Testing

In 2000, the CHE, identified the problems hindering access for PAI students to Israeli HEI, indicating the block created by the psychometric test, The committee recommended constructing pre-academic courses for PAI students and information and support centers in PAI localities, changes in the psychometric test contents, and programs to help ease integration of PAI in HEI campuses. However, these recommendations were mostly not implemented (Al Haj, 2003). In 2012, another committee appointed to study these issues proposed a five-year holistic program to improve access, assimilation, and support for PAI in Israel’s HEI. The committee made several policy recommendations: (i) development of pre-academic information and guidance centers; (ii) pre-academic preparation courses and improvement of the image of these courses; (iii) programs to support successful integration of PAI during first year of academic studies; (iv) improved enlistment of minorities to the academic faculty staff and institutional platforms; and (v) establishment of a scholarship fund ensuring financial support during studies (Shaviv, Benishtein, Ston, & Podam, 2013). It is hoped these recommendations will be implemented.

Today despite the obstacles involved in access, the university continues to be the preferred venue for the enrollment of PAI students. Approximately 35% of all PAI students in HE studied in 2012/2013 at Haifa University, which is located in the heart of the largely Arab Galilee, and nearly 16% in the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. 12% of all PAI students prefer to study at the Open University. 25% of PAI students, mainly female students, study in teacher education colleges, which still attract a large percentage of Arab students, especially the Arab colleges: al-Qasimi College in the Triangle area, and the College of Sakhnin in the Galilee region (Haj-Yehia & Arar, 2014).

Conclusions

The Israeli HE system began as a standardized system that failed to consider weak populations such as the PAI and other peripheral groups (Gibton, 2011; Sbirsky & Degan-Bouzaglo, 2009). Findings show that despite increasing numbers and percentages of PAI in Israeli HEI (especially female students), structural blocks have continued to hinder their access to certain HEI, including requirements for an especially high matriculation average, psychometric testing, and a minimum age threshold (Karletz et al., 2014). This situation is exacerbated by Arab students’ deficient preparation at the pre-academic stage (Al-Haj, 2003). The Arab education system does not adequately provide Arab school students with a stimulating learning environment to realize inherent abilities and equip them with 21st century skills.

Among the recommendations of the Planning and Budgeting Committee set up by the CHE (Shaviv et al., 2013) to improve access to HE for the PAI were suggestions for a form of corrective preference, recognizing the depth of the gap between Arab and Jewish achievements in education, that is, a policy of differential academic fees according to a socio-economic key, moderation of accumulative blocks in Arab education, greater autonomy for the Arab education center, opening information and guidance systems, encouraging Arab high school students to study HE and increasing their awareness of the academic process in pre-academic courses, opening streams to bypass psychometric testing, and limiting the weight of the psychometric test to at the most 50% of the calculated grade for university entrance (Shaviv et al., 2013). They also suggested annulling minimum age restrictions, adapting, and being more flexible with regard to admission interviews with consideration for linguistic and cultural difficulties. They proposed annulling discriminatory practices in the award of scholarships and university residence, greater respect for the language and culture of PAI students and encouragement of young researchers and affirmative action for their admission (Arar & Mustafa, 2011; Kirsh, 2010; Shaviv et al., 2013). These decisions of the CHE have yet to be supported by the necessary legislation with allocation of the necessary funding for implementation, supervision, and evaluation.

Our findings also showed how another solution attracted peripheral groups who encountered obstacles in entry to Israeli HE, so that they increasingly turned to study HE abroad (Arar & Haj-Yehia, 2013). Changes in policy regarding the acceptance of PAI to Israeli HE institutions could improve their access to tertiary education. “Affirmative action” legislation was applied successfully to improve university access for minorities in certain regions of the USA (Haj-Yehia & Arar, 2014). In order to facilitate university entrance for disadvantaged populations such as the PAI, Israeli universities should consider allocating minimal entrance percentages for promising minority students, without harming the principle of meritocracy, and assisting Arab students with guidance and instruction in their initial period of assimilation within the universities.

The expansion of HEI in Israel that began during the 1980s was among the greatest in the world. The HEI system has evolved in the past 30 years toward universal access and a differentiated system, responding to changing demands of the economy and workplace and to student’s different aspirations (Iram, 2011). Yet, steps that are more effective should be taken in order to equalize access to HE for the PAI minority and other peripheral populations in Israel. The underrepresentation of the PAI is inconsistent with the general percentage of HE expansion in Israel, and drives many PAI students to pursue their studies abroad (Arar & Haj-Yehia, 2013).

This chapter contributes to an understanding of the process of change in Israeli policies concerning HE for disadvantaged populations, especially citizens from the Palestinian minority. It points up inequity in these policies and investigates ways these populations have found to cope with barriers to their entry to Israeli HE institutions, including temporary migration to other countries. The findings may have international significance since similar difficulties are encountered in access to HE among underprivileged or peripheral populations in other world states.