Widening Access Through Higher Education Transformation

A Case Study of University of KwaZulu-Natal

Labby Ramrathan, University of KwaZulu-Natal, School of Education, South Africa

The aim of this chapter is to illuminate the contextual realities that have influenced the transformation agenda of higher education in South Africa. Through this illumination, the chapter presents various responses to this transformation agenda. These responses include a policy context response, institutional responses, and structural responses. The chapter, consequently aims to present the nature of these different responses and the emerging concerns with a view to showing that while these responses are opening up access to previously considered disadvantaged groups, other factors are now emerging that are and will threaten the transformational agenda of higher education.

The chapter argues that while the country, as a whole, has met its higher education access transformation agenda, the low student progression within higher education compromises these transformational gains. In attempting to address student progression, several initiatives have been instituted. These include student academic monitoring and support systems, the introduction of access and foundation programs, and, most recently, the review of the undergraduate curriculum. The chapter subsequently presents a reflection on these initiatives to show the complex nature of widening access and that each response tends to present another set of complex, unintended outcomes, suggesting that a simple solution to a complex problem is not the remedy in addressing widening access issues.

Keywords

Widening access; student progression; academic support

Introduction to Higher Education in South Africa

The latest national proposal to address low student graduation rates and high dropout rates in undergraduate studies at universities in South Africa comes in the form of a flexible undergraduate curriculum. This flexible undergraduate curriculum is also intended to address the low preparation level of potential university students by the school education system. How have we come to this national proposal? What informed its genesis? These are some of the questions that this chapter will address as I present a landscape of the imperatives, responses, challenges, and opportunities (perhaps lost) that necessitated a widening of access to higher education studies within the South African context.

Noting that South Africa is in its 21st year of democracy, most argue that it is presumptuous to believe that the ills of Apartheid will be reversed in this short period, yet for the majority of people affected by Apartheid, change is not happening quickly enough. Service delivery protest actions and student unrest (sometimes violent in nature) attest to the unhappiness of realizing any significant change to the material life of those marginalized through Apartheid. This is despite the great strides made across all sectors of government, including higher education, to redress the troubles of the past. This chapter presents a synopsis of the changes made to higher education in relation to the transformational agenda as presented in the White Paper 3: A Programme for the Transformation of Higher Education (Department of Education, 1997), related to governance, student access, student enrollment patterns, and institutional changes through mergers and incorporations. These changes are presented in greater detail in the next section of the chapter.

Access to higher education was largely the privilege of the White population group, with some institutions being reserved for African, Indian, and the Colored population groups respectively during the mainstream Apartheid era. Subsequently if students of different race groups wanted to access higher education institutions (HEIs) that were reserved for specific racial groups other than their own, they required governmental approval (Bunting, 2002). This process of accessing higher education slowly began to be dismantled as protest actions against the Apartheid policies and processes gained momentum in the 1980s to a point where racial quotas became the discourse in higher education enrolment. With the inception of a democratic, value-based constitution of South Africa, access to higher education acquired a different form. This chapter interrogates some of the latest issues relating to race-based access to higher education.

Finally, this chapter presents some research findings through an institutional case study, to illuminate the issues that institutions of higher education are facing within the context of a transforming higher education landscape.

Higher Education Transformation in SA—Focus on Access and Equity Issues Post-Apartheid

The increase in demand for higher education seems to be a worldwide phenomenon, with higher education capacity not increasing sufficiently to accommodate this increased demand. In the South African context, approximately 17% of those who complete their grade 12 school education access higher education across the 23 public funded institutions, in spite of the targeted enrollment plans of 20% in 2001 as indicated in the National Plan for Higher Education (Department of Education, 2001; Lewin & Mawoyo, 2014). The latest audited statistics indicate that in 2011, 931,817 students were enrolled in higher education across the public universities, growing from 495,000 in 1994. Table 12.1 presents a race based analysis of enrollment demographics across the public HEIs. Table 12.1 could be misleading if looked at only in terms of students enrolled in higher education against the institutional population demographics. A more nuanced picture appears when one considers participation rates in terms of the national population demographics as indicated in Table 12.2. While enrollment figures tell us the number of students per race category enrolled in higher education, participation rate is a more complex phenomenon where the enrollment of a particular race group is measured in terms of its proportional population demographics. For example, while 2% of the population of South Africa are Indians, the 6% enrolment of Indians in higher education constitutes a 47% participation rate amongst the Indian population group. This nuanced calculation means that, proportional to their population size, Indian students have a higher participation rate than African or colored students. Clearly from Table 12.2 it seems that the Indian and White population participation rates are much higher than those of the African and Colored population groups, suggesting that access to higher education for the African and Colored population groups is still marginal and unrepresentative of their population size.

Table 12.1

Race-based student enrollment in higher education (head count)

| 1993 headcount | 2011 headcount | % age enrolled against institutional demographics—2011 | |

| African | 213,000 | 640,442 | 68% |

| Colored | 34,600 | 59,312 | 6% |

| Indian | 34,700 | 54,698 | 6% |

| White | 212,900 | 177,365 | 9% |

| Total | 495,200 | 931,817 |

Table 12.2

Race-based participation rates

| 1993 | 2011 | % age of population groups—2011 | |

| African | 9% | 14% | 79% |

| Colored | 13% | 14% | 9% |

| Indian | 40% | 47% | 2% |

| White | 70% | 57% | 9% |

Source: Statistics for Tables 12.1 and 12.2 provided by Council for Higher Education, Vital Stats, 2014.

While the increase in enrollment since the dawn of democracy seems encouraging, issues of access are still very much a central discourse, especially within the context of quality education, student success, and graduation rates. There has been an abundance of literature on the transformation of higher education (see Cloete et al., 2002) ranging from setting the agenda for higher education transformation and implementing changes within higher education to reviews, reflections, critiques, and proposals for further changes. For the purpose of contextualizing this chapter, I present a synopsis of the transformational agenda, followed by a description of the interventions made to widen access into higher education as a delimit to the transformational agenda.

In mitigation of the injustices of the Apartheid governance, four major areas of higher education transformation formed the key elements of change. The first is related to the governance of higher education and the result of this change was to bring all public funded higher education into a single ministry of governance at the national level, enabling equity of educational provisioning across all public HEIs. Hence all these institutions are now governed by the National Department of Higher Education, each being guided by the same policy context. The second area of intervention related to the opening of access to higher education, with a special focus on increasing participation from previously disadvantaged groups. In this respect the enrollment of African students rose from 43% of total enrollment in 1994 to 67% in 2010 (African students are considered a distinct group from the generic Black nomenclature which comprised of African, Indian, and Colored—the distinctive racial groups that were considered disadvantaged during the Apartheid era). Using the generic nomenclature of Black, the enrollment increased from 55% in 1994 to 81% in 2011 (Lewin & Mawoyo, 2014), suggesting that participation of previously denied population groups has increased to reflect the demographics of our country. The third focus of the transformation agenda was to shift the enrollment patterns across study fields. The enrollment patterns in Humanities were much higher than those for the Sciences and Management Sciences. The transformation agenda sought to decrease enrollment in the Humanities to 40%, while increasing enrollments in Sciences and Management to 30% respectively. To a large extent this agenda has been met. The fourth agenda was focused on relandscaping the public HEIs through mergers and incorporations. This process sought to adjust the historical divide socially, economically, infrastructurally, and geographically. The outcome of this process saw the reduction of public HEIs from 36 during the Apartheid period to 23 (some with multicampuses) in 2004, with two more new institutions being developed in provinces that did not have any public HEIs.

Overall, there seems to be an overt sense that, as a national agenda, the transformation of higher education had achieved its intended goals. There is, however, growing concerns that this agenda is being threatened (Letseka & Maile, 2008; Ramrathan, 2013) with the realization that student graduation rates, quality of graduates, and equity of access will severely compromise gains made by the transformation charter. While, for example, the current demographics of higher education reflect the demographic population of South Africa, marginalized communities and sectors continue to be marginalized. Students who come from a schooling system that is largely dysfunctional, is rural or township based are still unable to access higher education suggesting that new forms of equity are needed to widen access and success within higher education. Furthermore, the complexity around educational provisioning, access to higher education, funding to support students, student mobility, and student experiences suggests that any simple solution to addressing such complex issues will be at best futile and will drive the education system into further disarray. The current proposal of a flexible curriculum (Council for Higher Education, 2013a, b), is such an example of a simple solution to a complex problem of student progression and graduation rates, a proposal that some argue (Pinar, 2014) is scantly substantiated by empirical evidence, and which is still influenced largely by economics and business interests.

Widening Access into Higher Education in South Africa

The phenomenon of widening access into higher education has its roots in the realization that in 1993, only 40% of the student population was African while 48% of the student population was White. The remainders were Indian and Colored with some being international. Considering that 79% of the population in South Africa is African, access to African students into higher education became a major focus of higher education transformation. However, recognizing the detrimental effect of Apartheid on the school education system, it was unrealistic to suddenly increase intake of African students into higher education. Hence a more planned approach was adopted and several processes unfolded. Academic support, funding, and student accommodation formed the core of intervention to widen access into higher education. In addition, institutional marketing became a central component of institutions through the establishment of administrative sections that were responsible for marketing and recruiting students. For the purpose of this chapter, academic intervention and funding will be privileged.

Student accommodation is currently receiving attention with institutions increasing their residence capacity to accommodate more students, especially from outlying regions. Institutional marketing has expanded significantly through school visits, promotional messages, and recruitment process through the print, online, radio, and film media. There are, however, concerns about the nature, form, and extent of these initiatives in terms of, for example, the language of these messages, the areas of reach, and the nature of marketing, suggesting that widening access through these media may also be limiting and discriminatory in nature.

Widening Access Through Academic Support

The academic interventions initially focused on potential university students who were still in school or first year of higher education. At the case study institution, located in KwaZulu-Natal, an initiative called Upward Bound Programme was conceptualized and implemented. In this program, potential grade 10 to 12 African learners were identified at schools located in rural and township schools. Top performing students in each of the selected schools were invited to participate in a winter and a summer program at the university each year. The program entailed students living on campus for two weeks during the winter vacation and two weeks during the summer vacation. The plan was that the identified students would start this program in grade 10 and continue until grade 12, but in most cases this did not materialize. Each year different students entered the winter and summer programs and to an extent compromised the intention of the program. The program was designed according to four principles. The first is to expose students to university life by living on campus and experiencing lectures, moving around campus, and seeking information and support from university staff, including the use of the library. The second was to provide students with additional academic support, especially in Math, Science, and English as these were deemed important subjects for student success within higher education. The third was to provide students with career counseling and life skills that would enable them to make appropriate decisions for further studies. The fourth was to provide the school from where the student came with teacher support materials and teacher development to continue with the support initiated at university when they returned to school. A tracer study of this program suggests that to an extent, this program was successful in widening access into higher education, indicating that half of the students who obtained university entrance grade 12 passes had enrolled in a HEI, not necessarily at the case study institution (Ramrathan, 2005).

Other interventions in widening access through academic support were in the form of access programs. These programs were designed to provide additional support to African students who did not gain admission criteria into a program. One of the limitations was that this program largely targeted the Math, Science, and Technology fields of study. Students were taken into the access programs for a whole academic year and if they had passed this access program, then they would be eligible for enrolling in the mainstream programs, including those in Humanities, Social Sciences, and Management studies. The access program focused on providing additional courses in Math, Science, and Languages. Access programs were largely funded by the respective institutions suggesting that the institutions absorbed the financial burden of providing these access programs. The implication of this was that institutions could not employ staff on long term contracts. This created uncertainties on staffing these programs, resulting in quick turnover of staff supporting them. A further complication was that the designers of the access programs did not teach in these programs due to their other institutional commitments. Hence training of staff to teach on these programs became a major limitation to the success. Institutions did complain, resulting in the national government making provisions in its funding process to cater for access programs which were considered a school level intervention. Consequently in order to justify funding, these programs needed to be reconceptualized into foundational programs that were to be integrated into the mainstream degree programs. Hence institutions extended their three and four year degree programs to include foundation modules resulting in the students taking an additional academic year to complete their degree.

The foundation programs were largely conceptualized within an epistemological access discourse and were grounded on the belief that while a student may gain physical access to HEIs, their conceptual access to the knowledge domain was lacking (Morrow, 2009). Hence, academic support was extended to supporting students through tutorials, support groups, peer learning, and mentor support. The target of intervention was on supporting students with the intention to provide opportunities for students to successfully complete their academic study. Subsequently institutions, including the case study institution, introduced structures and processes for academic support within the institutions. Academic support became a core function at the Deputy Vice Chancellors (DVC) level with a specific DVC being appointed for teaching and learning within higher education. In addition, a Dean of Teaching and Learning is appointed in each College to implement student academic support in their respective Colleges. At the School level, a Cluster leader for Teaching and Learning is appointed to provide specific support programs. The institution has a monitoring and tracking system that identifies students who are in need of monitoring, support, and tracking progress. A traffic light system is employed where students’ academic records are color coded. A green code would suggest that the student is progressing well, an orange code indicates that the student is not progressing according to progression rules. These students are compelled to meet with academic support coordinators and follow a support program to improve their academic performance. A red color code would indicate that the student is in danger of academic exclusion as s/he had not met progression requirements over a probationary period. Academic coordinators across the university have been employed to coordinate intervention programs to support students that are in need of this assistance.

While these initiatives and interventions were useful in supporting students, there were still concerns and critique of the conceptualization, methods, and outcomes of intervention. Some regarded these interventions as being a “deficit” model focus, that is, trying to fix students whose failure was seen as a result of individual attributes and skills (Boughey, 2005; McKenna, 2004) and believed that “students failed, not the institution.” In the institutional case study, academic support was found to be a simplistic response of mentoring, time management, and life skills, to a complex problem. Academic poor performance was found to be a symptom of a far deeper student experience discourse that distracted students from performing well academically. The concerns and critique led to a review of academic support that resulted in a broader conception of student support. The broader conception of student support now includes academic support, counseling support, financial support, housing support, and food security for students. These additional support structures and processes were aimed at providing a conducive environment for retaining students in their study program by removing potential detractors of academic success in students.

Based on the analysis of the gains made through these foundation and academic support programs and supported by a financial review that discovered how much the system is losing (financially) through high student dropout and low progression and graduation rates, the flexible curriculum for undergraduate studies has been proposed (Council for Higher Education, 2013a,b).

The flexible curriculum for undergraduate programs suggests that students be enrolled for an additional year of study which includes foundation modules across the degree program. The flexibility occurs in the form of exiting from this qualification a year earlier if the student does not need the additional foundational support. This means that in a four year extended program, a student can exit with a degree qualification in three years if that student does not need foundational academic support. This flexible curriculum has been conceptualized within the context of responding to the extremely low student progress to graduation. Literature (Council for Higher Education, 2013a,b; Letseka & Maile, 2008) suggests that student dropout and low graduation rates, including poor time-to-graduation, is largely related to the disadvantages of Apartheid in the form of poor preparation of students for higher education by the school education system, poverty, and social stratification based on economics and geography. However, from an institutional case study of student dropout over a three year period, researchers (Manik, 2014; Ramrathan, 2013) suggest that the reasons for student dropout and low progression and graduation rates are complex and include discourses on institutional and personal reasons that have been linked to student progress. In the case study institution, access to degree programs is based on excellence and due to the high number of applicants, students who have performed well in school education are generally selected. The selection process suggests that those entering into its programs are top school performers and therefore are well prepared for higher education studies. Personal circumstances, including those of financial resources, and institutional experiences are some of the prevailing reasons why students are not completing as anticipated. Hence the proposed flexible undergraduate curriculum may not necessarily be an appropriate response to, both, widening access (both physical and epistemological) and graduation rates. Rather than a fundamental review of the curriculum of degree programs in terms of composition of a curriculum and progression through the curriculum based on epistemology and relevance, proposal for a flexible undergraduate curriculum takes on a simplistic a response that privileges an economistic discourse.

Widening Access Through Financial Support

The funding response to widening access focused on the establishment of a national student funding scheme (NSFAS) at the national Department of Higher Education level. The financial scheme drew funding from the national higher education budget and over the years has grown to more than a billion rands. Students could access this funding if they had met certain criteria that privileged family affordability considerations. The funding caters for student tuition, residence, books, and living allowances, but does not cover the full value of these costs. Students have to obtain the difference from other sources. On completion of the degree program, students have to reimburse this funding as soon as they find employment. As there is limited funding, not all students who meet the criteria for funding are given the NSFAS loan. Students who do not meet progression requirements in their study program are also not given further funding. The implication of this kind of funding is that students are constantly in debt, even when they have completed their qualifications. More recently, part of this student loan debt has been converted to bursaries (especially at the final year level to encourage completion rates). Despite this relief, students will be in debt for a considerable time. The collection of this debt is also through the national tax system, suggesting that students cannot escape this burden.

The implication of this debt burden is that it would grow to such an extent that it could have the potential of disrupting the widening of access process and result in reversing the gains of the transformation agenda. As people continue to incur huge study debt, it would become a deterrent for other students and would therefore not be inspirational to take student loans for higher education studies. Hence the potential to access higher education by economically deprived communities would resist incurring further debt and would, therefore, not access higher education despite their ability to engage in further studies. A number of institutions, including the case study institution, have incurred student debt levels that are extremely high. These institutions are coerced into registering students in spite of the debt levels, largely through student protest actions.

Other funding opportunities do exist for students. These are, however, restricted to identified national priority areas. Two type of reserved funding are available. The first is a service linked bursary provided to students enrolling for teaching qualifications. Students who register for a teaching qualification specializing in any one of the identified priority areas are provided with full cost bursaries. After completion of study, the Department of Basic Education would deploy these teachers where the need has been located. These teachers are then expected to teach where they are deployed for a period equivalent to the number of years they received the bursary. The second funding opportunity is through the skills development fund, also a national earmarked fund for developing areas of skills shortage in the country.

The Cast Study of the University of KwaZulu-Natal: Student Access, Progression, and Graduation

The University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) is a multicampus institution located in the Province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. This institution was formed through the merger of the former University of Durban-Westville (UDW) and University of Natal (UN) during the institutional relandscaping process as part of the higher education transformation process. UDW was traditionally a university reserved for the Indian population of South Africa and UN was reserved for the White population group. UN was considered a privileged institution. UKZN is now the largest institution in South Africa with more than 45,000 students across undergraduate and postgraduate programs. Approximately 70% of the students are African, suggesting that this institution resonates with the national profile of students. With regard to national concerns about student progression, graduation, and dropout rates, I had been given an opportunity to engage in an institutional research on these phenomena. Using an explanatory mixed method approach (Creswell, 2009), I did a cohort analysis of student progression over a period of four years, taking three cohorts as my sampling process. The graduating cohort of 2010, 2012, and 2013 were used as points of reference. Students who had graduated in 2010, had, in fact, completed their qualification at the end of 2009. Hence a student who had enrolled as first entry students in a three year program would have commenced in 2007. This original cohort who commenced for the first time (in, for example, 2007) for the respective undergraduate degree was then used as the baseline statistics. This original cohort of students was then tracked to establish how many had completed their qualification in their minimum time of degree completion, how many had dropped out, and how many are still in their study program. The same was applied for the 2012 and 2103 graduating students.

Key Findings and Implications

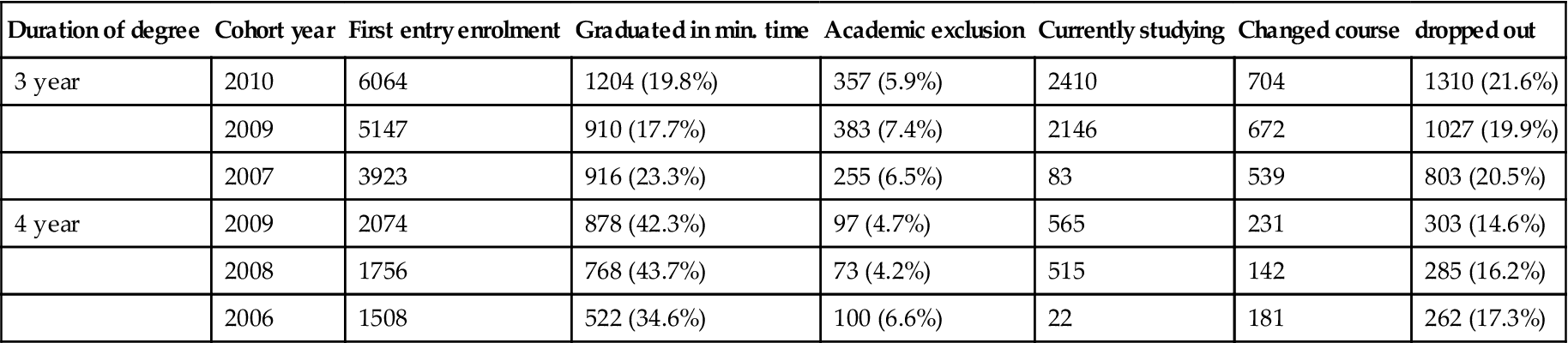

Table 12.3 shows that while efforts of widening access into higher education have been on the increase, the graduation rates, on average, are relatively low. Approximately one third of the students graduate in minimum time, while dropout and academic exclusions account for approximately 25% of the cohort. These figures are not very different from the national picture, suggesting that higher education in South Africa is becoming increasingly inefficient. This inefficiency is now being considered as a threat to the transformation agenda for higher education (Council for Higher Education, 2013a,b; Letseka & Maile, 2008; Ramrathan, 2013). Widening access into higher education has not yet had the desired outcome. Several reasons have been advanced for this state of admissions, progression, graduation, and dropout. The most obvious reasons of poor schooling, sociopolitical factors, and finance have been confirmed as factors for this national scenario. The institutional study, through its qualitative fine grained analysis, suggests that the above cited factors, do play some role, although are not the only factors. Wrong program and career choices, family responsibilities, personal problems, and institutional factors, such as poor lecturing quality, program load, and institutional social issues, were identified as contributory factors that account for the inefficient state of higher education. At UKZN students are selected on academic merit, suggesting that students who do enter the institution are above average students. Hence their ability to cope is not in question, as Manik (2014) found through her tracer study on students who dropped out of university. She found that more than 60% of the students who dropped out from UKZN had, in fact, accessed other HEIs and have completed their qualifications. Manik argues that, in the light of her findings, student dropout should be reconceptualized as student departure.

Table 12.3

Student cohort progression in undergraduate programs at The University of KwaZulu-Natal

| Duration of degree | Cohort year | First entry enrolment | Graduated in min. time | Academic exclusion | Currently studying | Changed course | dropped out |

| 3 year | 2010 | 6064 | 1204 (19.8%) | 357 (5.9%) | 2410 | 704 | 1310 (21.6%) |

| 2009 | 5147 | 910 (17.7%) | 383 (7.4%) | 2146 | 672 | 1027 (19.9%) | |

| 2007 | 3923 | 916 (23.3%) | 255 (6.5%) | 83 | 539 | 803 (20.5%) | |

| 4 year | 2009 | 2074 | 878 (42.3%) | 97 (4.7%) | 565 | 231 | 303 (14.6%) |

| 2008 | 1756 | 768 (43.7%) | 73 (4.2%) | 515 | 142 | 285 (16.2%) | |

| 2006 | 1508 | 522 (34.6%) | 100 (6.6%) | 22 | 181 | 262 (17.3%) |

Drawing from the institutional case study findings, there are several assumptions about who our students are and how they should progress through university study. It is assumed that students would start their qualification and complete it within three or four years following the rules of progression. It is also assumed that the students will be full-time students. These assumptions need to be reviewed in the light of more fine grained analysis that suggests that the majority of students do not complete in the minimum time of three or four years and that students enter and exit higher education as their personal circumstances may dictate. Institutions penalize students who do not complete their qualifications by creating, as referred to by Bourdieu (1984), a normalized process of academic support to assist these students in improving their academic performance, when academic competence was not the reason for performing poorly in higher education studies. This subtle contextual force on students is what I refer to as institutional violence, a concept that was developed by exploring the various moments within a student’s life in an institution where assumed norms within higher education are hurtful to students (Ramrathan, 2013).

Conclusion

In this chapter I have presented an overview of the transformational agenda of higher education that attempted to bring equity of provisioning and widening of access into higher education by the masses of the population. Understanding that South Africa is emerging from the disadvantages of Apartheid where the majority of the indigenous were denied opportunities from progress and development, redress processes have been institutionalized to affirm, support, and grow the participation of them in all spheres of development, including those of higher education.

Widening participation in higher education, has, to a large extent, been accomplished based on head count demographic profiles of institutions that resonate with national demographic statistics. However, participation rates are still skewed in favor of White and Indian students. The efforts to widen access of previously denied population groups, mainly the African group, are continuing. The latest is the proposal for the introduction of a flexible curriculum for undergraduate programs, which I believe is too simplistic a proposal to address the access into, participation of, and completion of a qualification. I believe that a more flexible higher education system needs to be conceptualized, one that is not specifically drawn on a business model of inputs, processes, and outputs, but one that would allow for students to enter and exit the higher education system based on students’ personal circumstances and needs. The building blocks are in place—a module system (where degrees are constituted through the accumulation of modules according to particular rules of combination of such modules) that allows for portability and transferability across the systems with credit recognition throughout the process of learning.

The number of public HEIs within South Africa limits the participation rates. Consideration needs to be given to how current higher education plants can be optimally used to increase participation as an initial attempt to increase participation. Ongoing consideration for increasing the number of institutions must occur to support widening of participation. Creation of mega institutions must not be seen as the only route to increasing the number of HEIs. Smaller institutions, located across the country would be a useful way to also widen participation by taking higher education to communities rather than the students leaving their communities to participate in these institutions.