AU 316: Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit1

AU-C 240: Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit

AU EFFECTIVE DATE AND APPLICABILITY

| Original Pronouncement | Statement on Auditing Standards (SAS) 99 |

| Effective Date | This standard currently is effective. |

| Applicability | Audits of financial statements in accordance with generally accepted auditing standards (GAAS). |

AU-C EFFECTIVE DATE

SAS No. 122, Codification of Auditing Standards and Procedures, is effective for audits of financial statements with periods ending on or after December 15, 2012.

AU-C 230 does not change extant requirements in any significant respect. The definition of fraud was changed to conform to ISA 240.

AU DEFINITIONS OF TERMS

Fraud. An intentional act that results in a material misstatement in financial statements that are the subject of an audit. The primary distinction between fraud and error is whether the underlying action that causes the misstatement of the financial statements is intentional or unintentional.

Fraud risk factors. Events or conditions that indicate incentives/pressures to perpetrate fraud, opportunities to carry out the fraud, or attitudes/rationalizations to justify a fraudulent action. These conditions may alert the auditor to a possibility that fraud may exist.

Misstatements arising from fraudulent financial reporting. Intentional misstatements or omissions of amounts or disclosures in financial statements designed to deceive financial statement users when the effect causes the financial statements not to be presented, in all material respects, in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP).

Misstatements arising from misappropriation of assets. The theft of an entity’s assets where the effect of the theft causes the financial statements not to be presented in conformity with GAAP (sometimes referred to as defalcation).

AU-C DEFINITIONS OF TERMS

Source: 240.11

Fraud. An intentional act by one or more individuals among management, those charged with governance, employees, or third parties, involving the use of deception that results in a misstatement in financial statements that are the subject of an audit.

Fraud risk factors. Events or conditions that indicate an incentive or pressure to perpetrate fraud, provide an opportunity to commit fraud, or indicate attitudes or rationalizations to justify a fraudulent action.

OBJECTIVES OF AU SECTION 316

The accounting profession has always had trouble explaining to critics why an audit conducted in accordance with professional standards might fail to detect a material misstatement of financial statements caused by fraud.

Over the years, there have been several pronouncements issued to attempt to explain the auditor’s responsibility for fraud detection. This section is the latest attempt.

In its March 1993 report In the Public Interest, the Public Oversight Board (POB) of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Practice section noted: “Attacks on the accounting profession from a variety of sources suggested a significant public concern over the profession’s performance. Of particular moment is the widespread belief that auditors have a responsibility for detecting management fraud which they are not now meeting.” The POB, in its report, made two recommendations addressing fraud. They were:

In 1993, AICPA’s Board of Directors issued a report, Meeting the Financial Reporting Needs of the Future: A Public Commitment from the Public Accounting Profession. In this report, AICPA’s Board of Directors supported recommendations and initiatives of others to assist auditors in the detection of material misstatements in financial statements resulting from fraud, and encouraged every participant in the financial reporting process—management, their advisors, regulators, and independent auditors—to share in this responsibility.

The Auditing Standards Board (ASB) decided to undertake a project on fraud in large measure because of the Expectation Gap Roundtable findings and the reports of the POB and the AICPA’s Board of Directors. In keeping with its commitment to serve the public interest by improving the detection of material fraud in financial statements, the ASB issued SAS 82, Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit, in 1997. SAS 82 provided expanded operational guidance on the consideration of fraud in conducting a financial statement audit. It also strengthened the auditor’s ability to fulfill his or her responsibility to plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether financial statements are free of material misstatements, whether caused by error or fraud.

After SAS 82 was issued, several developments occurred.

- The ASB formed the Fraud Research Steering Task Force, which sponsored five academic research projects to reexamine fraud.

- The POB’s Panel on Audit Effectiveness, in its “Report and Recommendations” in 2000, included a number of recommendations concerning earnings management and fraud.

- The International Auditing Practices Committee of the International Federation of Accountants issued International Standard on Auditing (ISA) 240, The Auditor’s Responsibility to Consider Fraud and Error in an Audit of Financial Statements. The ISA incorporated many of the concepts in SAS 82, but also provided guidance beyond that included in SAS 82.

In response to these developments, the ASB formed a new Fraud Task Force in 2000 to revise SAS 82. In 2002, the Auditing Standards Boards issued SAS 99, Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit. The new SAS does not change the auditor’s responsibility to plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free of material misstatement, whether caused by error or fraud. However, SAS 99 does establish specific new performance requirements and provides guidance to auditors in fulfilling that responsibility, as it relates to fraud.

OBJECTIVES OF AU-C SECTION 240

The objectives of the auditor are to:

FUNDAMENTAL REQUIREMENTS

Basic Requirement

In every audit, the auditor is obligated to plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free of material misstatement, whether caused by error or fraud.

Professional Skepticism

As defined in Section 100-230, professional skepticism is an attitude that includes a questioning mind and critical assessment of audit evidence. The auditor should conduct the entire engagement with an attitude of professional skepticism, recognizing that fraud could be present, regardless of past experience with the entity or beliefs about management’s integrity. The auditor should not let his or her beliefs about management’s integrity allow the auditor to be satisfied with any audit evidence that is less than persuasive. Finally, the auditor should continuously question whether information and evidence obtained suggest that material misstatement caused by fraud has occurred.

Engagement Team Discussion about Fraud (“Brainstorming”)

When planning the audit, members of the audit team should discuss where and how the financial statements may be susceptible to material misstatement caused by fraud. This discussion should include the following:

- Exchange ideas and brainstorm about where the financial statements are susceptible to fraud, how assets could be stolen, and how management might engage in fraudulent financial reporting.

- Emphasize the need to maintain the proper mindset throughout the audit regarding the potential for fraud. As previously discussed, the auditor should continually exercise professional skepticism and have a questioning mind when performing the audit and evaluating audit evidence. Engagement team members should thoroughly probe issues, acquire additional evidence when necessary, and consult with other team members and firm experts as needed.

- Consider known external and internal factors affecting the entity that might create incentives and opportunities to commit fraud, and indicate an environment that enables rationalizations for committing fraud.

- Consider the risk that management might override controls.

- Consider how to respond to the susceptibility of the financial statements to material misstatement caused by fraud.

- For the purposes of this discussion, set aside any of the audit team’s prior beliefs about management’s honesty and integrity.

The discussion would normally include key audit team members. Other factors that should be considered when planning the discussion include:

- Whether to have multiple discussions if the audit involves more than one location

- Whether to include specialists assigned to the audit

Audit team members should continue to communicate throughout the audit about the risks of material misstatement due to fraud.

Obtaining Information Needed to Identify Fraud Risks

In addition to performing procedures required under Section 311, Planning and Supervision, the auditor should obtain information needed to identify the risks of material misstatement due to fraud by:

- Asking management and others within the entity about their views on the risk of fraud and how such risks are addressed.

- Considering unusual or unexpected relationships identified by analytical procedures performed while planning the audit.

- Considering whether any fraud risk factors exist.

- Considering other information that may be helpful in identifying fraud risk.

Inquiries of Management

The auditor should make the following inquiries of management:

- Does management know about actual or suspected fraud?

- Have there been any allegations of actual or suspected fraud from employees, former employees, analysts, regulators, short sellers, and others?

- Does management understand the entity’s fraud risk, including any identified risk factors or account balances or classes of transactions for which a fraud risk is likely to exist?

- What programs and controls does the entity have to help prevent, deter, and detect fraud? How does management monitor such programs?

- When there are multiple locations, how are operating locations or business segments monitored? Is fraud more likely to exist at any one of the locations or business segments?

- Does management communicate its views on business practices and ethical behavior to employees, and if so, how?

- Has management reported to the audit committee or equivalent body how the entity’s internal control prevents, deters, and detects fraud?

When evaluating management’s responses to these inquiries, auditors should remember that management is often in the best position to commit fraud. Therefore, the auditor should determine when it is necessary to corroborate those responses with other information. When responses are inconsistent, the auditor should obtain additional audit evidence.

Inquiries of the Audit Committee

The auditor should make the following inquiries of the audit committee:

- What are the audit committee’s (or at least the chair’s) views of the risk of fraud?

- Does the audit committee know about actual or suspected fraud in the entity?

The auditor should also understand how the audit committee oversees the entity’s assessment of fraud risks and the mitigating programs and controls.

Inquiries of Internal Auditors

The auditor should make the following inquiries of internal auditors:

- What are the internal auditors’ views on the risk of fraud?

- Have the internal auditors performed procedures to identify or detect fraud during the year?

- Has management satisfactorily responded to any finding from procedures performed to identify or detect fraud?

- Are the internal auditors aware of any actual or suspected fraud?

Inquiries of Others within the Organization

The auditor should also ask others within the entity whether they are aware of actual or suspected fraud, using professional judgment to determine to whom these inquiries are made and how extensive the inquiries should be. The following are examples of people that may provide helpful information and, therefore, that the auditor may wish to consider directing inquiries to:

Considering the Results of Analytical Procedures

When performing the required analytical procedures in planning the audit as discussed in Section 329, Analytical Procedures, the auditor may find unusual or unexpected relationships as a result of comparing the auditor’s expectations with recorded amounts or ratios developed from such amounts. The auditor should consider those results in identifying the risk of material misstatement due to fraud.

The auditor should also perform analytical procedures relating to revenue with the objective of identifying unusual or unexpected relationships involving revenue accounts that may indicate a material misstatement due to fraudulent financial reporting. Examples of such procedures include:

- Comparing sales volume with production capacity (sales volume greater than production capacity might indicate fraudulent sales)

- Trend analysis of revenues by month and sales return by month shortly before and after the reporting period (the analysis may point to undisclosed side agreements with customers to return goods)

Although analytical procedures performed during audit planning may be helpful in identifying the risk of material misstatement due to fraud, they may only provide a broad indication, since such procedures use data aggregated at a high level. Therefore, the results of such procedures should be considered along with other information obtained by the auditor in identifying fraud risk.

Considering Fraud Risk Factors

Using professional judgment, the auditor should consider whether information obtained about the entity and its environment indicates that fraud risk factors are present, and, if so, whether it should be considered when identifying and assessing the risk of material misstatement due to fraud.

Examples of fraud risk factors are presented in Illustrations 1 and 2. These risk factors are classified based on the three conditions usually present when fraud exists:

Considering Other Information

The auditor should evaluate other information that may be helpful in identifying fraud risk. The auditor should consider:

- Any information from procedures performed when deciding to accept or continue with a client

- Results of review of interim financial statements

- Identified inherent risks

- Information from the discussion among engagement team members

Identifying Fraud Risks

Attributes

The auditor should use professional judgment and information obtained when identifying the risks of material misstatement due to fraud. The auditor should consider the following attributes of the risk when identifying risks:

- Type (Does the risk involve fraudulent financial reporting or misappropriation of assets?)

- Significance (Could the risk lead to a material misstatement of the financial statements?)

- Likelihood (How likely is it that the risk would lead to a material misstatement of the financial statements?)

- Pervasiveness (Does the risk impact the financial statements as a whole, or does it relate to an assertion, account, or class of transactions?)

The auditor should evaluate whether identified fraud risks can be related to certain account balances or classes of transactions and related assertions, or whether they relate to the financial statements as a whole. Examples of accounts or classes of transactions that might be more susceptible to fraud risk include:

- Liabilities from a restructuring because of the subjectivity in estimating them

- Revenues for a software developer, because of their complexity

Presumption about Improper Revenue Recognition as a Fraud Risk

Since fraudulent financial reporting often involves improper revenue recognition, the auditor should ordinarily presume that there is a risk of material misstatement due to fraudulent revenue recognition.

Consideration of the Risk of Management Override of Controls

The auditor should also recognize that, even when other specific risks of material misstatement are not identified, there is a risk that management can override controls. The auditor should address this risk as discussed in the section below on “Addressing the Risk of Management Override.”

Assessing Identified Risks

As part of the understanding of internal control required by Section 319, the auditor should

Responding to the Results of the Assessment

The auditor responds to assessment of risk of material misstatement due to fraud by:

- Exercising professional skepticism

- Evaluating audit evidence

- Considering programs and controls to address those risks

Examples of the use of professional skepticism would include:

- Designing additional or different audit procedures to obtain more reliable evidence

- Obtaining additional corroboration of management’s responses or representations

The auditor should respond to the risk of material misstatement in the following ways:

If the auditor concludes that it is not practical to design audit procedures to sufficiently address the risks of material misstatement due to fraud, the auditor should consider withdrawing from the engagement and communicating the reason to the audit committee.

Overall Response to Risk

Judgments about the risk of material misstatements due to fraud may affect the audit in the following ways:

Adjusting Audit Procedures

The auditor may respond to identified risks by adjusting the nature, timing, and extent of audit procedures performed. Specifically

- The nature of procedures may need to be modified to provide more reliable and persuasive evidence, or to corroborate management’s representations. For example, the auditor may need to rely more on independent sources, physical observation of assets, or computer-assisted audit techniques.

- The timing of procedures may need to be changed. For example, the auditor may decide to perform more procedures at year-end, rather than relying on tests from an interim date.

- The extent of procedures applied should reflect the assessment of fraud risk and may need to be adjusted. For example, the auditor may increase sample sizes, perform more detailed analytical procedures, or perform more computer-assisted audit techniques.

Additional examples of ways to modify the nature, timing, and extent of tests to respond to the fraud risk assessment, examples of responses to identified risks arising from fraudulent financial reporting, and examples of responses to risks from misstatements arising from the misappropriation of assets can be found in “Techniques for Application.”

Addressing the Risk of Management Override

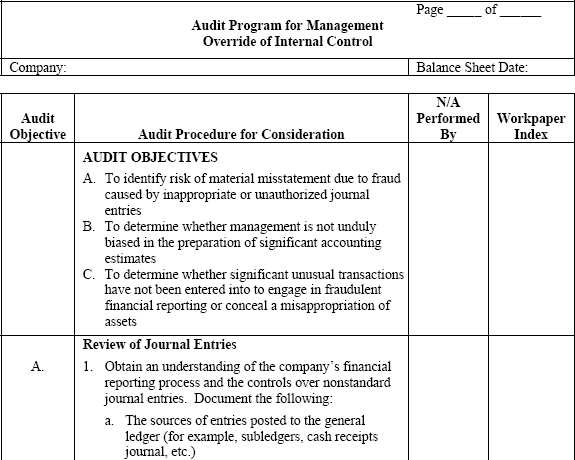

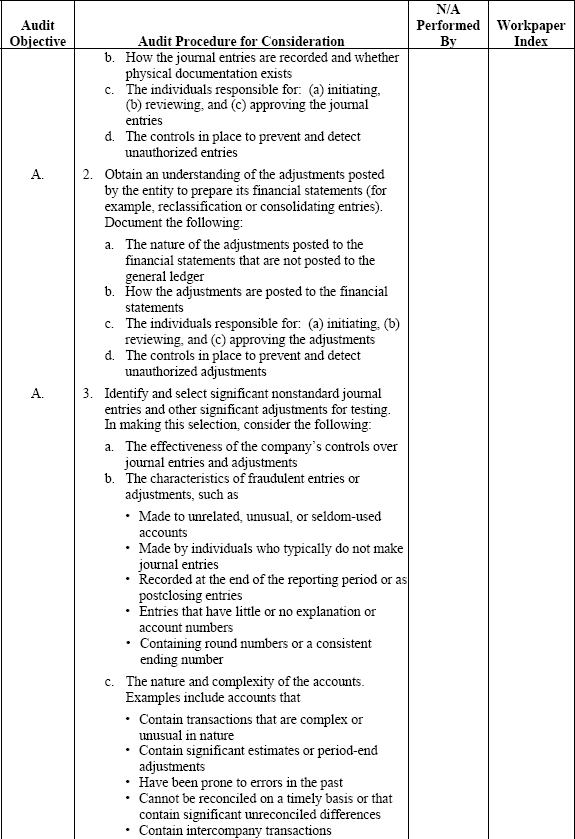

The auditor should perform the following procedures to specifically address the risk for management’s override of controls.

Examine journal entries and other adjustments for evidence of possible material misstatement due to fraud, and test the appropriateness and authorization of such entries. The following procedures should help the auditor in addressing possible recording of inappropriate or unauthorized journal entries or making financial statement adjustments, such as consolidating adjustments, report combinations, or reclassifications not reflected in formal journal entries. The auditor should specifically:

- What is our assessment of the risk of material misstatement due to fraud? (The auditor may identify a specific class of journal entries to examine after considering a specific fraud risk factor.)

- How effective are controls over journal entries and other adjustments? (Even if controls are implemented and operating effectively, the auditor should identify and test specific items.)

- Based on our understanding of the entity’s financial reporting process, what is the nature of evidence that can be examined? (Regardless of whether journal entries are automated or processed manually, the auditor should select journal entries to be tested from the general ledger, and examine support for those items. In addition, if journal entries and adjustments are in electronic form only, the auditor may require that an information technology [IT] specialist extract the data.)

- What are the characteristics of fraudulent entries or adjustments, or the nature and complexity of accounts? Illustration 3 provides a worksheet to use in identifying characteristics of fraudulent journal entries or adjustments, or accounts that may be more likely to contain inappropriate journal entries or adjustments. (When audits involve multiple locations, the auditor should consider whether to select journal entries from various locations.)

- Are there any journal entries or other adjustments processed outside the normal course of business, (i.e., nonstandard or nonrecurring entries)? The auditor should consider placing additional emphasis in identifying and testing items processed outside the normal course of business, because such items may not be subject to the same level of internal control as other entries.

Reviewing accounting estimates for biases that could result in fraud. The auditor should consider whether differences between amounts supported by audit evidence and the estimates included in the financial statements, even if individually reasonable, indicate a possible bias on the part of entity’s management. If so, the auditor should reconsider the estimates taken as a whole.

The auditor should retrospectively review significant accounting estimates in prior year’s financial statements to determine whether there is a possible bias on the part of management. (Significant accounting estimates are those based on highly sensitive assumptions or significantly affected by management’s judgment.) The review should provide information to the auditor about a possible management bias that can be helpful in evaluating the current year’s estimates. If a management bias is identified, the auditor should evaluate whether the bias represents a risk for material misstatement due to fraud.

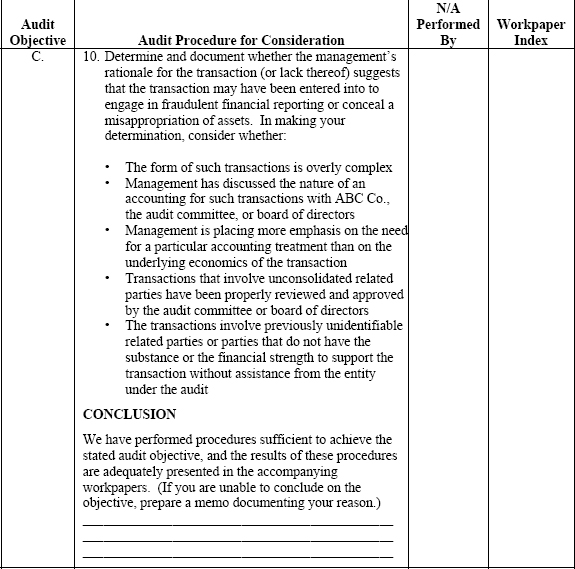

Evaluating whether the rationale for significant unusual transactions is appropriate. Personnel at the entity engaged in trying to hide a theft or commit fraudulent financial reporting might use unusual or nonstandard transactions to conceal the fraud. The auditor should understand the business rationale for such transactions and whether the rationale suggests that the transactions are fraudulent. When evaluating the transactions, the auditor should consider:

- Is the transaction overly complex?

- Has management discussed the nature and accounting for the transaction with the audit committee or board of directors?

- Is management focusing more on achieving a particular accounting treatment than the underlying economics?

- Have any transactions involving special purpose entities or other unconsolidated related parties been approved by the audit committee or board of directors?

- Do transactions involve previously unidentified related parties?

- Do transactions involve parties that cannot support the transaction without the help of the audited entity?

Evaluating Audit Evidence

The auditor should:

Assessing the Risk of Material Misstatements Due to Fraud

The auditor should continuously assess the risk of material misstatement due to fraud throughout the audit. The auditor should be alert for conditions that may change or support a judgment regarding the risk assessment. These conditions are listed in Illustration 4.

Evaluating Analytical Procedures

The auditor should consider whether analytical procedures performed as substantive tests or in the overall review stage of the audit indicate a risk of material misstatement due to fraud. The auditor should perform analytical procedures relating to revenue through the end of the reporting period, either as part of the overall review of the audit or separately. If not included during the overall review stage of the audit, the auditor should perform analytical procedures specifically related to potentially fraudulent revenue recognition.

The auditor should be alert to responses to inquiries about analytical relationships that are:

- Vague or implausible

- Inconsistent with other audit evidence

Evaluating Fraud Risk at or Near the Completion of Fieldwork

The auditor should, at or near the end of fieldwork, evaluate whether the results of auditing procedures and observations affect the earlier assessment of the risk of material misstatement due to fraud. When making this evaluation, the auditor with final responsibility for the audit should confirm that all audit team members have been communicating information about fraud risks to each other throughout the audit.

Responding to misstatements that may result from fraud. When misstatements are identified, the auditor should consider whether they are indicative of fraud. The auditor may need to consider the impact on materiality and other related responses.

If the auditor believes that the misstatements are or may result from fraud, but the effect is not material to the financial statements, the auditor should evaluate the implications for the rest of the audit. If the auditor determines that there are implications, such as implications about management’s integrity, the auditor would reevaluate the assessment of the risk of material misstatement due to fraud and its impact on the nature, timing, and extent of substantive tests and the assessment of control risk if control risk were assessed below the maximum.

If the auditor believes that the misstatements are fraudulent, or may result from fraud, and the effect is material (or if the auditor cannot evaluate the materiality of the effect) the auditor should:

After evaluating the risk of material misstatement, the auditor may determine that he or she should withdraw from the engagement and communicate the reason to the audit committee. The auditor may wish to consult legal counsel when considering withdrawing from the engagement.

Communication about Possible Fraud to Management, the Audit Committee, and Others

The auditor should communicate any evidence that fraud may exist, even if such fraud is inconsequential, to the appropriate level of management.

The auditor should directly inform the audit committee about:

- Fraud involving senior management

- Fraud that causes a material misstatement of the financial statements

The auditor should reach an understanding with the audit committee about the nature and extent of communications that need to be made to the committee about misappropriations committed by lower-level employees.

The auditor should consider whether the following are reportable conditions that should be communicated to senior management and the audit committee:

- Identified risks of material misstatement due to fraud that have continuing control implications (whether or not transactions or adjustments that could result from fraud have been detected)

- A lack of, or deficiencies in, programs and controls to mitigate the risk of fraud

The auditor may also want to communicate other identified risks of fraud to the audit committee, either in the overall communication of business and financial statement risks affecting the entity or in the communication about the quality of the entity’s accounting principles (see Section 380).

Ordinarily, the auditor is not required to disclose possible fraud to anyone other than the client’s senior management and audit committee, and in fact would be prevented by the duty of confidentiality from doing so. However, a duty to disclose to others outside the entity may exist when:

The auditor may wish to consult legal counsel before discussing these matters outside the client to evaluate the auditor’s ethical and legal obligations for client confidentiality.

Documentation

The auditor should document:

- The engagement team’s discussion, when planning the audit, about the entity’s susceptibility to fraud; the documentation should include how and when the discussion occurred, audit team members participating, and the subject matter covered

- Procedures performed to obtain the information for identifying and assessing the risks of material misstatements due to fraud

- Specific risks of material misstatement due to fraud identified by the auditor, and a description of the auditor’s response to those risks

- If improper revenue recognition has not been identified as a risk factor, the reasons supporting such conclusion

- The results of procedures performed that addressed the risk that management would override controls

- Other conditions and analytical relationships that caused the auditor to believe that additional procedures or responses were required, and any other further responses to address risks or other conditions

- The nature of communications about fraud to management, the audit committee, and others

INTERPRETATIONS

There are no interpretations for this section.

PROFESSIONAL ISSUES TASK FORCE PRACTICE ALERTS

98-2 Professional Skepticism and Related Topics

This Practice Alert was written after SAS 82 was issued and highlighting two areas that warrant professional skepticism and attention to audit evidence.

98-3 Responding to the Risk of Improper Revenue Recognition

This Practice Alert notes that much of the litigation against accounting firms and a number of SEC Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases involve revenue recognition issues. This Practice Alert:

- Reminds auditors of certain factors or conditions that can indicate improper, aggressive, or unusual revenue recognition practices

- Suggests ways that auditors may reduce the risk of failing to detect such practices

- Reminds auditors that one should ordinarily presume that improper revenue recognition is a fraud risk factor for all audits

- Reminds auditors of their responsibilities to communicate with the board of directors and audit committees

03-02 Journal Entries and Other Adjustments

This Practice Alert assists auditors in designing and performing audit procedures regarding journal entries and other adjustments. Highlights of the alert include guidance on:

- How to understand the entity’s financial reporting process and its controls over journal entries and other adjustments.

- How to assess the risk of material misstatement from journal entries and other adjustments, including when such entries exist only in electronic form. The alert also suggest that auditors discuss, in their brainstorming session, the ways in which management could originate and post inappropriate entries or adjustments, the kinds of unusual combinations of debits and credits to watch for, and the types of entries and adjustments that could result in a material misstatement that might not be detected by standard audit procedures.

- Making inquiries about fraud of those involved in the financial reporting process. The alert recommends that where practical, and regardless of the fraud risk assessment, the auditor should ask (1) accounting and data entry personnel about whether those individual were asked to make unusual entries, and (2) selected programmers and IT staff about any unusual and/or unsupported entries.

- Evaluating the completeness of journal entry and other sources of adjustments. Since journal entries and other adjustment may be made outside the general ledger, the auditor should completely understand how the various general ledgers are combined and the accounts grouped to create the consolidated financial statements.

- Identifying and selecting entries and adjustments for testing. The alert points out that the auditor may need to employ CAATs to identify entries and adjustments to test. These techniques are often designed to detect entries made at unusual times of day, by unusual users, or electronic entries not documented in the general ledger.

- Testing other adjustments, including comparing the adjustments to underlying supporting information, and considering the rationale underlying the adjustment and the reason it was not in a formal journal entry.

- Documenting the results of procedures related to journal entries and other adjustments.

TECHNIQUES FOR APPLICATION

Management’s Responsibilities

Management is responsible for designing and implementing programs to prevent, deter, and detect fraud. When management and others, such as the audit committee and board of directors, set the proper tone of proper ethical conduct, the opportunities for fraud are significantly reduced.

Description and Characteristics of Fraud

Although fraud is a broad legal concept, the auditor’s interest specifically relates to fraudulent acts that cause a material misstatement of financial statements. Two types of misstatements are relevant to the auditor’s consideration in a financial statement audit.

Fraudulent financial reporting and misappropriation of assets differ in that fraudulent financial reporting is committed, usually by management, to deceive financial statement users while misappropriation of assets is committed against an entity, most often by employees.

Fraud generally involves the following three conditions:

However, not all three conditions must be observed to conclude that there is an identified risk. It is particularly difficult to observe that the correct environment for rationalizing fraud is present.

The auditor should be aware that the presence of each of the three conditions may vary, and is influenced by factors such as the size, complexity, and ownership of the entity. These three conditions usually are present for both types of fraud.

The auditor should also be alert to the fact that fraudulent financial reporting often involves the override of controls, and that management’s override of controls can occur in unpredictable ways. Also, fraud may be concealed through collusion, making it particularly difficult to detect.

Although fraud usually is concealed, the presence of risk factors or other conditions may alert the auditor to its possible existence.

Fraud Risk Factors

Fraud risk factors may come to the auditor’s attention while performing procedures relating to acceptance or continuance of clients, during engagement planning or obtaining an understanding of an entity’s internal control, or while conducting fieldwork. Accordingly, the assessment of the risk of material misstatement due to fraud is a cumulative process that includes a consideration of risk factors individually and in combination. As noted earlier, assessment of fraud risk factors is not a simple matter of counting the factors present and converting to a level of fraud risk. A few risk factors or even a single risk factor may heighten significantly the risk of fraud.

Identifying Fraud Risks

When identifying fraud risks, the auditor may find it helpful to consider information obtained along with the three conditions—incentives/pressures, opportunities, and attitudes/rationalizations—that are usually present when fraud exists. However, as stated above, the auditor should not assume that all three conditions must be present or observed. In addition, the extent to which any condition is present may vary.

The size, complexity, and ownership of the entity may also affect the identification of fraud risks.

Modifying the Nature, Timing, and Extent of Audit Procedures to Address Risk

According to AU 316.53, the following are examples of ways to modify the nature, timing, and extent of tests in response to identified risks of material misstatement due to fraud:

- Perform unannounced or surprise procedures at locations

- Ask that inventories be counted as close as possible to the end of the reporting period

- Orally confirm with major customers and suppliers in addition to sending written confirmations

- Send confirm requests to a specific party in an organization

- Perform substantive analytical procedures using disaggregated data, such as comparing gross profit or operating margins by location, line of business, or month to auditor-developed expectations

- Interview personnel involved in areas where a fraud risk has been identified to get their views about the risk and how controls address the risk

- Discuss with other independent auditors auditing other subsidiaries, divisions, or branches the extent of work that should be performed to address the risk of fraud resulting from transactions and activities among those components

Examples of Responses to Identified Risks of Misstatements from Fraudulent Financial Reporting

The following examples are from AU 316.54:

Revenue recognition. The auditor may consider:

- Performing substantive analytical procedures relating to revenue using disaggregated data, such as comparing revenue reported by month or by product line or business segment during the current reporting period with comparable prior periods

- Confirming with customers certain relevant contract terms and the absence of side agreements, because the appropriate accounting often is influenced by such terms or agreements (for example, acceptance criteria, delivery and payment terms, the absence of future or continuing vendor obligations, the right to return the product, guaranteed resale amounts, and cancellation or refund provisions often are relevant in such circumstances)

- Inquiring of the entity’s sales and marketing personnel or in-house legal counsel regarding sales or shipments near the end of the period and their knowledge of any unusual terms or conditions associated with these transactions

- Being physically present at one or more locations at period-end to observe goods being shipped or being readied for shipment (or returns processing) and performing other appropriate cutoff procedures

- For those situations for which revenue transactions are electronically initiated, processed, and recorded, testing controls to determine whether they provide assurance that recorded revenue transactions occurred and are properly recorded

Inventory quantities. The auditor may consider:

- Examining the entity’s inventory records to identify locations or items that require specific attention during or after the physical inventory count

- Performing additional procedures during the count, such as rigorously examining the contents of boxes, checking the manner in which goods are stacked for hollow squares, or examining the quality of liquid substances for purity, grade, or concentration

- Performing additional testing of count sheets, tags, or other records to reduce the possibility of subsequent alteration or inappropriate compilation

- Performing additional procedures to test the reasonableness of quantities counted, such as comparing quantities for the current period with prior periods by class or category of inventory or location

- Using CAATs

Management estimates. The auditor may want to supplement the audit evidence obtained. The auditor may

- Engage a specialist

- Develop an independent estimate for comparison

- Evaluate information gathered about the entity and its environment

- Retrospectively review similar management judgments and assumptions from prior periods

Examples of Responses to Identified Risks of Misstatements Arising from Misappropriation of Assets

The auditor will usually direct a response to identified risks of misstatements arising from misappropriation of assets to certain account balances. The scope of the work should be linked to the specific information about the identified misappropriation risk. The auditor may consider some of the procedures listed in “Examples of Responses to Identified Risks of Misstatements Arising from Fraudulent Financial Reporting.” However, in some cases, the auditor may:

- Obtain an understanding of the controls related to preventing or detecting the misappropriation and testing of such controls

- Physically inspect assets near the end of the period

- Apply substantive analytical procedures, such as the development by the auditor of an expected dollar amount at a high level of precision to be compared with a recorded amount

Evaluating Analytical Procedures as Part of Audit Evidence

As part of the auditor’s evaluation of analytical procedures performed as substantive tests or in the overall review stage of the audit, and those analytical procedures that relate to revenue through the end of the reporting period, the auditor may find it helpful to consider the following issues:

- An unusual relationship between net income and cash flows from operations may occur if management recorded fictitious revenues and receivables but was unable to manipulate cash.

- Inconsistent changes in inventory, accounts payable, sales or cost of sales between the prior period and the current period may indicate a possible employee theft of inventory, because the employee was unable to manipulate all of the related accounts.

- Comparing the entity’s profitability to industry trends, which management cannot manipulate, may indicate trends or differences for further consideration.

- Unexplained relationships between bad debt write-offs and comparable industry data, which employees cannot manipulate, may indicate a possible theft of cash receipts.

- Unusual relationships between sales volume taken from the accounting records and production statistics maintained by operating personnel—which may be more difficult for management to manipulate—may indicate a possible misstatement of sales.

In planning the audit, the auditor will most likely use a list of fraud risk factors to serve as a “memory jogger.” This list may be taken from the examples listed in the next section (“AU Illustrations”), or the examples provided may be tailored to the client. The documentation of this list of fraud risk factors considered is not required, but represents good practice.

During the planning and performance of the audit, the auditor may identify some of the fraud risk factors from the list as being present at the client. Of those risk factors present, some will be addressed sufficiently by the planned audit procedures; others may require the auditor to extend audit procedures.

Required Actions/Communication Required for Discovered Fraud

When the auditor discovers or suspects fraud, the actions and communications required are somewhat complex, especially when an SEC client is involved. The actions/communications required by Title III of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, by the SEC Practice section (SECPS) for its members, and by the SEC in Form 8-K add to the complexity.

The best approach is to decide which of the following three situations governs and follow the guidance presented below for the applicable situation.

Situation 1.

Section 316 Actions/Communications Requirements for Material Fraud + Any Fraud Involving Senior Management for Non-SEC Clients

Auditor should:

Situation 2.

Section 316 Actions/Communications Requirements for Material Fraud + Any Fraud Involving Senior Management for SEC Clients

Auditor should:

- Auditor’s resignation

- Auditor’s conclusion that the information coming to his/her attention has a material impact on the fairness or reliability of the client’s financial statements or audit report and that this matter was not resolved to the auditor’s satisfaction before resignation

Situation 3.

Section 316 Actions/Communication Requirements for Immaterial Fraud + Not Involving Senior Management for All Clients (Public and Nonpublic)

Auditor should:

Antifraud Programs and Controls

The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) framework does not include a discussion related to the prevention and detection of fraud. An established set of criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of fraud-related controls does not exist. However, the SEC guidance does suggest that management may find helpful information in the document “Management Anti-Fraud Programs and Controls,” which was published as an exhibit to Section 316, Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit.

The guidance in that document is based on the presumption that entity management has both the responsibility and the means to take action to reduce the occurrence of fraud at the entity. To fulfill this responsibility, management should:

- Create and maintain a culture of honesty and high ethics

- Evaluate the risks of fraud and implement the processes, procedures, and controls needed to mitigate the risks and reduce the opportunities for fraud

- Develop an appropriate oversight process

In many ways, the guidance offered in “Management Anti-Fraud Programs and Controls” echoes the concepts and detailed guidance contained in the COSO report. The primary difference is that the antifraud document reminds management that it must be aware of and design the entity’s internal control to specifically address material misstatements caused by fraud and not limit efforts to the detection and prevention of unintentional errors.

Culture of Honesty and Ethics

A culture of honesty and ethics includes these elements:

- A value system founded on integrity.

- A positive workplace environment where employees have positive feelings about the entity.

- Human resource policies that minimize the chance of hiring or promoting individuals with low levels of honesty, especially for positions of trust.

- Training—both at the time of hire and on an ongoing basis—about the entity’s values and its code of conduct.

- Confirmation from employees that they understand and have complied with the entity’s code of conduct and that they are not aware of any violations of the code.

- Appropriate investigation and response to incidents of alleged or suspected fraud.

Evaluating Antifraud Programs and Controls

The entity’s risk assessment process (as described in the separate chapter on AU 311) should include the consideration of fraud risk. With an aim toward reducing fraud opportunities, the entity should take steps to:

- Identify and measure fraud risk

- Mitigate fraud risk by making changes to the entity’s activities and procedures

- Implement and monitor an appropriate system of internal control

Develop an Appropriate Oversight Process

The entity’s audit committee or board of directors should take an active role in evaluating management’s:

- Creation of an appropriate culture

- Identification of fraud risks

- Implementation of antifraud measures

To fulfill its oversight responsibilities, audit committee members should be financially literate, and each committee should have at least one financial expert. Additionally, the committee should consider establishing an open line of communication with members of management one or two levels below senior management to assist in identifying fraud at the highest levels of the organization or investigating any fraudulent activity that might occur.

AU ILLUSTRATIONS

- Ineffective communication, implementation, support, or enforcement of the entity’s values or ethical standards by management or the communication of inappropriate values or ethical standards.

- Nonfinancial management’s excessive participation in or preoccupation with the selection of accounting principles or the determination of significant estimates.

- Known history of violations of securities laws or other laws and regulations, or claims against the entity, its senior management, or board members alleging fraud or violations of laws and regulations.

- Excessive interest by management in maintaining or increasing the entity’s stock price or earnings trend.

- A practice by management of committing analysts, creditors, and other third parties to achieve aggressive or unrealistic forecasts.

- Management failing to correct known reportable conditions on a timely basis.

- An interest by management in employing inappropriate means to minimize reported earnings for tax-motivated reasons.

- Recurring attempts by management to justify marginal or inappropriate accounting on the basis of materiality.

- The relationship between management and the current or predecessor auditor is strained, as exhibited by the following:

- Disregard for the need for monitoring or reducing risks related to misappropriation of assets.

- Disregard for internal control over misappropriation of assets by overriding existing controls or by failing to correct known internal control deficiencies.

- Behavior indicating displeasure or dissatisfaction with the company or its treatment of the employee.

- Changes in behavior or lifestyle that may indicate assets have been misappropriated.

- Is the entry made to an unrelated, unusual, or seldom-used account?

- Is the entry made by an individual who typically does not make journal entries?

- Is the entry made at closing of the period or postclosing with little or no explanation or description?

- Do entries made during the preparation of financial statements lack account numbers?

- Does the entry contain round numbers or a consistent ending number?

- Does the account consist of transactions that are complex or unusual in nature?

- Does the account contain significant estimates and period-end adjustments?

- Has the account been prone to errors in the past?

- Has the account not been regularly reconciled on a timely basis?

- Does the account contain unreconciled differences?

- Does the account contain intercompany transactions?

- Is the account otherwise associated with an identified risk of material misstatement due to fraud?

- Discrepancies in the accounting records, including

- Conflicting or missing evidential matter, including

- Problematic or unusual relationships between the auditor and management, including

1 The section is affected by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board’s (PCAOB) Standard, Conforming Amendments to PCAOB Interim Standards Resulting from the Adoption of PCAOB Auditing Standard No. 5, An Audit of Internal Control Over Financial Reporting Performed in Conjunction with an Audit of Financial Statements.

2 Fraud that involves senior management or fraud that causes a material misstatement of the financial statements should be reported directly to the audit committee.

3 Management incentive plans may be contingent upon achieving targets relating only to certain accounts or selected activities of the entity, even though the related accounts or activities may not be material to the entity as a whole.