PRINCIPLE

TWO

CHOOSE

THE BEST TEAM

CHAPTER SUMMARY

1. Why your team selection is vital.

2. What a winning team looks like.

3. how to match your team with the client’s by role and personality.

You’ve decided to go for the bid.

Not only must you select the team, it must be the best possible team. If you merely field the people who are available and not the best, or wheel out the same old team, you’re immediately at a disadvantage. Ernst & Young research showed clearly that clients buy the team first, then the firm. People buy from people.

You could argue that Ernst & Young’s global reputation would be enough to reassure any buyer, so the firm was never going to be an issue. But in my experience, whatever the size of the bidding organization, clients judge the team first and the organization second.

“The difference was the strength of the team. They were very impressive and there wasn’t a point of weakness.”

A regional manufacturing client

Fielding your best team also differentiates you from the competition and signals to the client that you mean to win:

“The fact that their team seemed so right gave an impression of more commitment.”

An international construction client

And you must be clear, both to the client and internally, that the team that wins the work will do the work. No ‘bait & switch’, please, where you field your best, most experienced team to win the tender, then have a junior team turn up to do the work. You don’t want a reputation for doing that in your marketplace.

Clearly not every organization is a Big Four accountancy firm or management consulting practice that can pick and choose from a large pool of qualified people. Maybe you’re an SME and your choice of personnel is limited. In that case it’s even more important that you make the link between a team member’s experience and their proposed role on the bid explicit to the client.

WHAT DOES ‘THE WINNING TEAM’ LOOK LIKE?

Here’s my ‘get out of jail’ card: the best team is the most attractive one to the client. As every client is different, each bid team should be different, too. The most attractive teams:

1. Are competent, i.e. can do the job

2. Match the client’s needs, selection criteria and style

3. Are clear about their roles and responsibilities

4. Demonstrate strong personal qualities

5. Are ones the client has had a hand in choosing

6. Have informed views on the client’s business.

Let’s look at these in more detail.

1. COMPETENCE. Your ability to do the job (‘proficiency’) is a given. Most clients will assume you are competent, especially if you’ve passed the public sector PQQ (Pre-Qualification Questionnaire, Principle 1) and they’ve invited you to submit a formal response or to present at a pitch. If you doubt your technical ability to deliver against the contract, you shouldn’t be bidding. But this won’t be an issue if you’ve pre-qualified properly.

In my experience, many bidders go wrong here: they think that proving their technical competence will carry the day, so they invest most of their energy and resources into that aspect of their response. But that proof is merely the baseline for your bid and the client’s expectations. It’s essential but not sufficient to win the contract.

What carries the day is showing the client how you will apply that technical competence to their particular issue or need. And that benefits-led demonstration needs to be concrete, specific, detailed and compelling. We cover this in more detail in chapter 4 when we discuss your written submission.

Most clients seek new ideas and approaches, couched under ‘added value’. So the people you choose must not only be competent, but must also bring something different and special to the table. Examples include legal expertise in IP (intellectual property) for SMEs, experience of horizontal well drilling for oil and gas in extreme formations, or the ability to deliver transformational training in writing skills.

2. MATCH THE CLIENT. The idea of matching, mirroring or level-selling when choosing your team is a principle of rapport-building – we tend to like and follow people who we think are like us. The challenge is to match your team members with their opposite numbers in the client in terms of role, grade and experience. Common sense suggests that the people who will be working closest together on the contract need to get on and see eye to eye both professionally and personally.

We must also match the client’s diversity in terms of age, race and gender, especially in the voluntary and community sector. I heard about a company bidding for a contract to audit a regional drug rehabilitation charity. The bidder sent along three white, middle-aged males… only to find that the selection panel comprised two Afro-Caribbean women and a young white male. The mis-match was stark.

Mirroring the client is also about recognizing their psychological needs, such as needing ‘comfort’. This is typically provided by fielding a senior person in your team, often referred to as ‘the grey hair’ or the ‘safe pair of hands’. Their ‘been-there-done-it-got-the-T-shirt’ experience reassures the client that the team is unlikely to be thrown by an issue or obstacle they’ve never seen before.

You can use this reassurance factor in bids where you’re facing a new bidder on the block. If you’re up against a young, dynamic start-up that’s getting the client’s attention, point out to them that youthful energy comes with a price tag – inexperience.

3. ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES. These must be crystal-clear, otherwise you’ll confuse the client. Here are the four main questions that most clients need answered when they’re assessing a bid team:

1. Who’s the captain? Who’s leading the bid?

2. Whom will I see most of when the contract’s running?

3. Who’s ultimately accountable for the team’s performance?

4. Whom can I go to if things start to go wrong?

In a partnership, such as a law firm or accounting practice, the bid is likely to be led by a partner (1); he or she may well also answer for the team’s performance (3). The person delivering the nuts and bolts of the contract, however, will probably be relatively junior, e.g. an audit manager in an accountancy practice, or an Associate or Client Services Manager in a law firm (2). And if the client needs to go over the head of the bid leader, then there is usually someone playing a role that I would call ‘Client Relationship Manager’ who oversees all their firm’s dealings with the client’s organization (4). This is the professional services firm equivalent of a Key Account Manager.

When clarifying roles and responsibilities, sporting analogies come into their own.

When the England rugby team was thrashed 36-0 by South Africa in the pool stage of the 2007 World Cup in France, everyone wrote them off as the worst defence of a World Cup ever (if you’re not into rugby or were on a different planet at the time, England had won the World Cup in 2003). But they went on to beat Australia and France (and lose to the Springboks again in the final). In an article in The Sunday Times, Josh Lewsey, a top England player, explained that the team was confused about how they should play. They stopped the rot by clarifying everyone’s role:

As the meeting went on and with everyone coming from different clubs with each of them posessing different game plans, it became clear that there was genunine confusion about how we were trying to play. We needed a simplified, unified plan and for everyone to understand their roles within it. The answer was obvious. The decision-makers on the field who played at nine, 10 and 12 should describe what they needed in a clear, concise manner to the players around them.

The following day the decision-makers made a presentation about how they felt the team should play.

FIGURE 2.1. Clarifying roles and responsibilities Extract from an interview in The Sunday Times with England rugby player Josh Lewsey on the importance of clarifying players’ roles.

4. PERSONAL QUALITIES. If you accept that the technical competence of your team or the delivery of a technical service is a given, then what sets your team apart from the competition is their personal qualities. These come in a pick ’n’ mix bag of Cs: chemistry, charm, confidence, credibility, consistency, character and communication skills.

“In terms of audit policy, there’s not going to be a lot of difference between them. It’s a personal chemistry thing.”

A national engineering consultancy client

Chemistry is the ability to strike a rapport with your opposite number quickly and easily; to connect with them. This is a combination of attitude and skill; both can be learnt. Although some people are better at it than others, it’s not innate.

The trick is to focus not on yourself and your needs, but on the other person – in this case, the client. See the world from their perspective, find out what they value, how they want to be treated. In other words, be buyercentric, not bidder-centric.

The skill is to understand one of the secrets of rapport-building: if you (discreetly) mirror their body image with your own, you will find it easier to relate to what they are saying, thinking and feeling. Just make sure you err on the side of mirroring their behaviour rather than mimicking it. People instinctively know if you’re making fun of them or being insincere.

Charm is closely related to chemistry. It’s about putting the other person first and making them feel there and then as if they’re the most important person in the world to you. It’s a subtle form of flattery.

Confidence comes from several sources, including healthy self-esteem, solid expertise and long experience. You need to approach the bid ‘with faith’ (the original meaning of ‘confidence’) that you can solve their problems and address their needs. It’s linked to having a ‘can-do’ attitude that nothing is too much trouble, all problems have a solution and you will do whatever it takes to find it.

Communication skills are too big a subject to cover here in depth, but they include the ability and desire to listen actively and hear the client’s underlying message, as well as explain complex technicalities to non-technical people in plain English, without patronizing them. People underestimate the ability to listen to another person non-judgementally, without interference from their own commentary, analysis or self-talk.

Credibility is more to do with how the client perceives you, i.e. your believability. Do they heed your views and opinions? Do people listen when you speak? Clients need to feel convinced within seconds of you opening your mouth that you know what you’re talking about. No matter how brilliant your message, if you lack credibility with the recipient, it won’t land.

Consistency means that the client knows they’re going to get the same level of commitment, quality and delivery from you, whatever the circumstances. Consistency and service predictability breed trust, and trust breeds repeat business.

Character is about the deep-seated values and personal traits that distinguish you and make the client trust you. These include honesty, integrity and transparency. I’m a great believer in always telling the truth, whatever the consequences. If you make a mistake, own up and put it right. I’ve seen bids where a team member did just that and rectified the error so well that it ended up strengthening his relationship with the client.

There are two personal qualities that, when combined with the Cs above, can transform a team from good to great: Desire and Enthusiasm.

As in any competitive activity, you have to want to win. Desire is stronger than need: it’s the source of your creative energy, your stamina and your readiness to do what it takes to win. A marketing consultant I know called Bernadette says “Successful people do what unsuccessful people are not prepared to do.” If you’re not gagging to win, don’t bid.

And genuine enthusiasm is a rare quality in business today. Again, it generates energy, not just for the enthusiast, but also for the people around them; it infects them. This viral quality makes the enthusiast attractive to us, especially if they’re being enthusiastic about our business. As a client once said to me:

“We want to work with people who want to work with us. We’re the most important company to us and we want them to match that level of enthusiasm.”

5. LET THE CLIENT CHOOSE THE TEAM. Provided you have a pool of people to choose from, give the client a hand in the selection of the delivery team. That will make them feel closer to and more engaged in your bid, making it harder for them to reject it. Position it not as your team, but theirs.

And if you can’t offer them several candidates for the same position, at least demonstrate how and why they are the best person for the job. So rather than present the client with a standard CV of the candidate, tailor it: make the link between their proposed role on the job and their experience explicit.

6. HAVE AN INFORMED VIEW ON THE CLIENT’S BUSINESS. Another finding of research into bids and tenders is that clients worth their salt value robust views on their business, provided those views are well researched and thought through. I call this ‘commercial personality’. Even if the client disagrees with you when you meet them in the pre-submission meetings (next chapter), strong views trigger a conversation that will stimulate them, get them thinking differently about their issues, and make them respect you.

“The guy I met was interested in the business. He had ideas, so you could actually have a discussion with him…”

A banking client

The alternative of just going in there to ‘fill your information buckets’ is a non-starter. That will bore the client and could well dash your bid there and then. By expressing your commercial personality, you’re differentiating yourself from the competition.

The bottom line is that, if you think through the client’s needs and help them gain new insights into them, you’ve added value before you’ve even put pen to paper.

HOW DO YOU CHOOSE THE WINNING TEAM?

You choose the best team not in a vacuum, but as a function of the requirements of the contract and of the client’s team. And you need to consider two dimensions of every member of the client team:

• their role in the buying process

• their personality.

I often hear the buying organization in a bid referred to as ‘the client’, as you might expect. That’s fine, as long as you don’t assume that all the client decision-makers involved in the bid are somehow clones of each other who share the same agenda, concerns and goals. They’re not and they don’t. Each member of the buying group or ‘decision-making unit’ (DMU) is different, and you need to treat them as such. To do that, you need to understand the five most common roles in a buying group:

1. The Boss

2. The Money Person

3. The End-User

4. The Expert

5. The Guide or The Enforcer.

Here are the generalized characteristics of each, plus the filter through which they will typically assess your bid:

ROLE |

CHARACTERISTICS & MOTIVATION |

Bid filter |

The Boss |

Most senior decision-maker, aka the MD, CEO or business owner. Concerned with high-level, strategic, organizational outcomes. Less interested in the detail of how you do it, more interested in what they get when they hire you, i.e. the results. Motivated by a mix of personal and corporate goals, e.g. retire early, protect their bonus, be recognized as a success (‘make me look good’), see value of stock options rise, boost shareholder value, enter new markets/defend existing ones, protect the organization’s reputation or public image. |

• Strategic, highlevel results or outcomes • Organizational / corporate • Long-term •Personal gain |

The Money Person |

Usually the Finance Director, this is the budget holder. They have their hand on the purse strings, sign the cheques and have the authority to spend money. They usually work closely with The Boss. Only interested in your product or service from the perspective of cost vs. benefit. Motivated by value for money and getting the best possible deal for their organization. |

• ROI (return on investment) • Value for money • The bottom line • Payback period |

The End-User |

Regularly uses or manages the product/service. Interested in its performance, features, functionality, ease of use and reliability. May be relatively junior in the buying group, but often responsible for developing the tender spec or ITT/RFP. Motivated by what’s best for them, their business function and their team. |

• Functional, operational • Detail • Often relatively junior |

The Expert |

The ‘techie’ or geek. H as deep technical knowledge of the product/ service, as well as its competitors and industry trends. Interested in its supply, features, specification, maintenance and applications, including future-proofing. May use jargon. Motivated by how it works rather than what it does for the organization. |

• Technical, operational • Detail, features, ‘spec’ |

The Guide / The Enforcer |

Often an external consultant or advisor hired by The Boss, this role is harder to assess and less predictable than the others. Often asks deceptively simple but tough questions. May bring insights from other industries, sectors or cultures. Motivated by the need to add value quickly, make The Boss look good and put bidders through their paces. Typically less interested in long-term relations with bidders; they can afford to be tough with you. If the role is internal, then it’s usually filled by Procurement. |

• Varies, but usually strategic / organizational (mirroring The Boss’s filter) • ROI, value for money • The bidding process • Proposals best practice |

These roles are not always clear-cut. Several roles may merge in one person or, in a large organization, several people may share one role, e.g. where they are responsible for different elements of a complex product or service.

As you might expect, the most senior and influential role is No. 1, The Boss. He or she is typically the MD or CEO of the client organization and carries the most clout. They will often only read the executive summary and base their vote – and their recommendation to their subordinates – on that section alone. So make sure you read Principle 4.5, ‘Write a Cracking Executive Summary’.

Many bids mistakenly focus on operational or functional content, to the detriment of the strategic business case or organizational outcomes. Yet this is what The Boss is most interested in. ‘If you want my vote, speak my language’ applies to each role.

I recently worked with an international oil and gas company. Being full of engineers developing leading-edge technology, that’s what they tend to write about in their bids. That’s their comfort zone, their preoccupation; that’s what they spend their waking hours thinking about.

But their clients’ CEOs are more interested in the performance value that that technology delivers. They’re more interested in what they get with the technology than what the technology does. The moment you link your price to the value that the technology adds to the client’s performance, the higher premium you can charge.

Having said that, don’t now focus solely on The Boss and neglect the other four roles. Proposals best practice says that to get the vote of each client decision-maker and win, the bidder must hit the hot buttons of the holders of all five roles.

DECISION-MAKERS’ PERSONALITY

After the role of each decision-maker in the buying process, the second dimension we need to consider is their personality.

There are several approaches to identifying different personality types. One of the best known is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). This is a self-reporting test that identifies a person’s likely preferences across four pairs of opposing personality tendencies: introversion/extraversion, sensing/intuitive, thinking/feeling, and judging/perceiving.

This in-depth analysis of personality generates 16 possible personality types, and I don’t propose to go into these here. Much has been written online and offline about MBTI, and many swear by it. Besides not being an expert in this approach, however, I feel that it’s too detailed for the hothouse of a bid, when we need to be able to assess the personality of our client stakeholders quickly and easily. You can’t exactly ask each of them to take an MBTI test, can you? I prefer a behaviour model called Relationship Awareness Theory.

Developed in the 1970s by Elias Porter at the Counselling Centre of the University of Chicago under the direction of top psychologist Carl Rogers, the model is based on the belief that all human beings share one motive – to self-actualize, i.e. to fulfil their potential. This means that behaviour must not be viewed as an end in itself, but as a vehicle that moves us to higher self-worth or self-esteem.

Everyone achieves this self-esteem in different ways, which Porter called ‘motivational styles’. Our motivational style influences our behaviour choices in all situations. So our behaviour is the result of our predominant motivational style.

Picture a buoy bobbing about on the waves, anchored to the seabed. The buoy is our behaviour, which may change depending on circumstances; the anchor is our motivational style, which is constant.

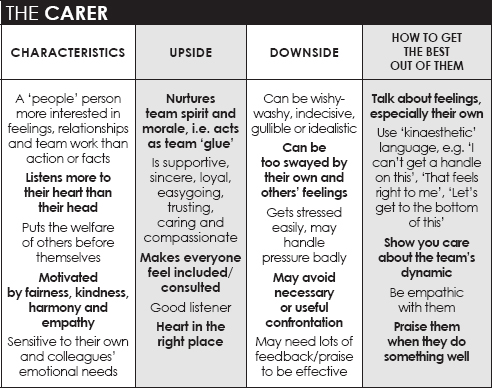

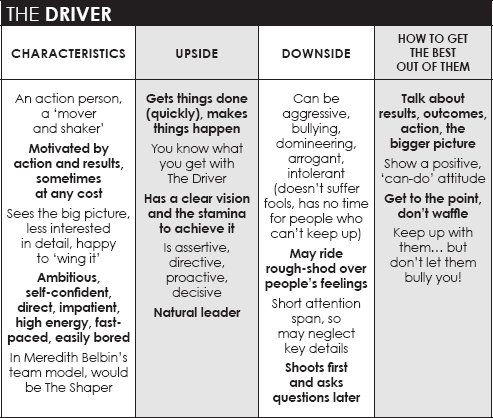

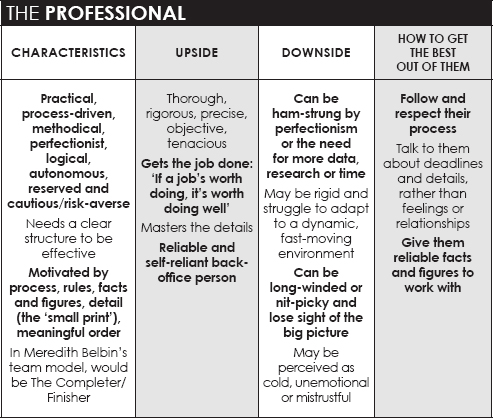

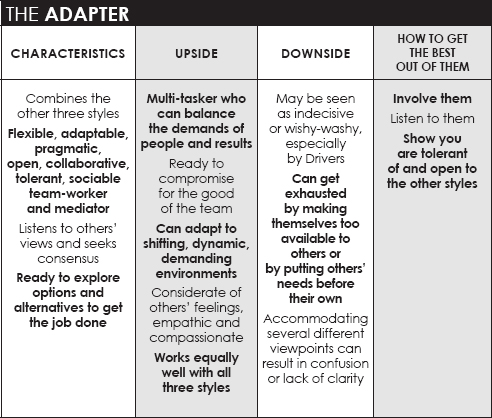

Porter identified four motivational styles: Carer, Driver, Professional and Adapter.

In brief, Carers are motivated by feelings and relationships; Drivers are motivated by getting things done; Professionals are motivated by meaningful order; Adapters are motivated by being flexible and keeping their options open. The table below includes more detailed characteristics of each style, their upside and downside, and how to get the best out of each.

You may find that your client’s decision-making roles and their motivational styles overlap. For example, many Bosses tend to exhibit symptoms of the Driver style, while Experts or End-Users often conform to the Professional style.

I recommend you create what I call a decision-makers’ matrix when you analyze the client pre-submission. Map each person’s role in the buying group, their motivational style, their perception of you and your organization, your contact with them (if any), who else in your organization knows them, and any other information that will serve you as a team when you’re planning your response to their tender.

Then use your meetings with the client (next chapter) to build on that data and assemble the right team for the client. Your aim here is to match each member of your team with their opposite number in the client in terms of role and personality. Once you’ve settled on the team’s composition, however, don’t just file and forget the matrix. This document can keep you and your team on track as you work your way through the tendering process. Treat it as a live document that you build on as you learn more and more about the client and their organization. When you’re planning and drafting the bid document and designing the oral presentation (if there is one), you’ll find it a useful reminder of all the major issues you need to be addressing.

WHAT’S THE RISK OF NOT DOING THIS PRE-WORK?

If you don’t consciously think about the client decision-makers in this systematic way, you’re likely to create a proposal that is exactly the kind of proposal you’d like to receive, but that may not resonate with the client. The best proposals reflect the language, style and needs of the client, i.e. they are buyer-centric, not bidder-centric. This is based on a core tenet of rapport-building and empathy: that people tend to most closely identify with and be influenced by people who show they understand them and who they think are most like them.

WINNER TAKES ALL BOTTOM LINE:

To influence the buyers and their decision-making process, you must understand their buying role and motivational style, and talk to them in the right way about the right things at the right time.

[ FOOD FOR THOUGHT ]

Working alone or with your bid team colleagues, think about a recent tender you responded to. Identify the buying role and motivational style of each of the decision-makers. In hindsight, did you or your team engage with them throughout the process in a way that they would respond best to?

Score your handling of each decision-maker, then note what you could or should have done differently. Take those insights into your next bid.

When you next hold a bid review/‘wash-up’ session at the end of a tender, why not run this exercise with your colleagues, to look at the buying role and motivational style of each decision-maker?

Alternatively, if you support proposals in your organization, for example as a business development manager, think about the motivational style of your bid colleagues. How can you modify your behaviour to get the best out of them on your next bid?