PRINCIPLE

FIVE

PRESENT A POWERFUL PITCH

CHAPTER SUMMARY

1. The purpose of the pitch.

2. Which pitch slot to take.

3. Designing and practising your pitch.

4. Debriefing your pitch.

5. Some myths about presenting.

PURPOSE: WHAT’S THE PITCH (OR PRESENTATION) FOR?

A pitch is a formal, face-to-face presentation to the client of your proposed solution or value proposition. Its purpose is not to entertain, educate, inform, introduce new team members or recap the document. It’s to persuade the client to appoint you. And it’s your last chance to do so.

You do that by answering all their doubts, concerns and questions, by convincing them that you are as good as you said you were in the bid document (if there was one). To win, you need to ensure that the client answers ‘Yes’ to these questions about you:

• ‘Do they offer us more value for money than any other bidder?’

• ‘Do they understand us and our business?’

• ‘Are they a team?’

• ‘Are they keen to work with us?’

• ‘Can we work with them?’

Also known as the ‘beauty parade’ or ‘interview’, the pitch is probably the only time that all of them will meet all of you. So they’re likely to make things tough for you, because they want to see how you fare under pressure, how well you think on your feet and how strong a team you are. They’ll stress-test you, seeking reasons to reject you. Many teams have blown it at this stage with a lacklustre presentation, while other teams have come from behind to snatch the win.

It’s all about your performance on the day. It’s a stage-managed theatrical show, with a cast, lines, steps and choreography… and you’ve got to get it all right. The client will extrapolate your performance and their impression of you on the day to what it will be like working with you in the weeks and months ahead. Pitching is a brief, intense and pivotal experience. It’s the shooting star of business development.

WHICH PITCH SLOT TO TAKE

So you need to prepare thoroughly. But you can’t do that until and unless you know how long you’ve got to present, which slot you’ve been given, what you’re going to say and who’s going to say it.

If you have any choice at all over your slot, ask the client if you can go either first or last.

If all the pitches are due to take place over a short period, like a day, then go first. Based on the theory of primacy, the thinking behind this is that you will set the tone and the standard for the other bidders to follow. If you’re brilliant, the client may decide there and then to appoint you.

If, however, the presentations are held over a longer period, like a week, then it’s best to go last, based on the theory of recency. The client is more likely to remember the last presentation they heard on Friday than the first one on Monday. But going last at the end of a gruelling week for the client has implications for content and length. You may want to cut to the chase (solution + client benefits) even sooner than you originally intended, to keep their attention and make their decision easy.

DESIGNING AND PRACTISING YOUR PITCH

How much time is your presentation slot? An hour? However much or little time the client has given you, you’ve got less than you think.

Research conducted by the Learning Point Presentations School found that the proportion of the client’s final decision attributed to the formal presentation is a mere 25%; the Q&A accounts for a whacking 75%! That’s because the client thinks that in the Q&A they’re seeing you ‘unplugged’, in the raw. What they don’t know is that you’ve worked your socks off anticipating 90% of their likely questions and prepping your answers.

So if your slot is 60 minutes, you need to prepare a 15- to 20-minute presentation, with the remaining time allotted to the Q&A. This has profound implications for what you prioritize and how you allocate your prep time.

Let’s deal with the formal presentation first.

‘WHO’S MY PITCH TEAM?’

Your first major decision is whom to take.

The team you take to the presentation should be dictated by whom the client is expecting to see, i.e. the team roles that matter most to them.

Find out (by asking) who will attend from the client and match them with your people in terms of role, grade, experience, style and culture. This is the same concept of mirroring/level-selling that we explored in Principle 3: ‘Meet the client pre-submission’. Each member of the client panel needs to recognize their opposite number on your team.

If you’ve had pre-submission meetings with the client and they’ve gone well, it makes sense for the same people to present. The client will recognize them and be comfortable with them.

If for any reason you decide to involve a new team member in the pitch, give the client early warning of that and, if you can, introduce the new person to them beforehand. If that’s not possible, at the very least explain to the client why you are adding them to the team and what they bring to the party. New people fielded at this stage will find it much harder to build rapport than in those earlier meetings, due to the formality of the pitch event.

There must be logic and balance in your team selection too, with both apparent to the client. And everyone you take must speak. Don’t be tempted to take ‘bag-carriers’ or note-takers. I was once involved in a pitch where the senior partner decided to take his secretary to record the meeting. In the debrief after we’d learnt that we’d lost, the client wondered why she was there and added that he’d found her silent presence a distraction.

Also – and forgive me if this is obvious – it doesn’t make sense to take someone just to answer a certain type of question in the Q&A, if they don’t also have a part in the formal presentation. If that question doesn’t come up, they’ll have sat there looking (and probably feeling) redundant.

Your team needs to be culturally appropriate, too.

I once heard about a consultancy bidding for a local authority contract to advise them on workforce diversity. The bid team that turned up comprised four white, middle-aged men… who had to present to a panel of ethnically diverse women in their 20s and 30s. Oops.

Though not a tendering example, a printing company I know run solely by Muslims was sent a Christmas hamper full of wine and chutneys by one of their clients. A box of chocolates at Eid would have been more thoughtful.

WHAT TYPES OF DECISION-MAKER CAN YOU EXPECT TO SEE ON THE CLIENT PANEL?

Broad brush, the client panel will usually comprise representatives of the five typical buyer roles that we explored in Principle 3. Here’s a quick reminder:

THE BOSS |

The ultimate authority and decision-maker. Motivated to achieve strategic, organizational goals; often visionary. Their assessment of you will tend to be: strategic. |

THE MONEY PERSON |

Signs the cheques. Able to allocate funds and release or withhold budgets. Interested in roI. Their assessment of you will tend to be: commercial. |

THE END-USER |

Uses or manages the product or service regularly. Interested in features, functionality, ease of use, reliability. Their assessment of you will tend to be: operational. |

THE EXPERT |

Has deep technical understanding of the product or service and its competitors. Interested in features, supply, application, future-proofing. Their assessment of you will tend to be: technical. |

THE GUIDE/THE ENFORCER |

May or may not be a user of the product or service. If external, they may be a consultant brought in by The Boss to give informed, objective advice. If internal, they are likely to be from Procurement. If external, their assessment of you will tend to be: pragmatic, i.e. whatever helps justify their involvement in the process. If Procurement, their assessment of you will tend to be: price-based. |

If you asked for and got meetings with the client pre-submission, you should already have sussed out who occupies each of these roles. If not, you’ll be hard pushed in the pitch to match your people accurately with theirs.

If you submitted a written document, you will already have developed win-themes and main messages, so designing the message content of your pitch should be relatively easy. But you also need to overlay those messages onto the five hot buying buttons identified in the table above: strategic, commercial, operational, technical, and pragmatic/cost. This will not only influence what you say, but how you say it. So take the members of your team most appropriate to give those messages and press those buttons. This is not about charisma, but the most logical presenters to give those messages.

At the very least, the people who must attend the pitch are:

• The captain of your team, i.e. whoever leads your bid and is answerable for delivery and overall service quality

• Whomever the client will see most of in the delivery of the contract, e.g. the audit team, the training deliverers, the merger team, the legal associates

• A product/service expert who can answer the client’s technical concerns.

Bringing in the great and the good at the last minute is risky

Avoid wheeling in a senior person at this stage of the tender process, unless there is a very good reason to do so. This can disrupt the team’s internal bonds and the client’s perception of you as a team. A senior person brought in to rescue a flagging bid can also dominate proceedings, again destroying the teamwork carefully nurtured over weeks or months.

In their bid to host the 2012 Olympics, France brought in the Paris mayor, Jacques Chirac, at the 11th hour to show commitment to their pledges in the bid document. Leaks from inside the French camp claimed, however, that this move undermined the esprit de corps that the team had developed over many months of working together. And we all know who won the bid to host the 2012 Olympics.

Another example was England’s 2011 bid to host the 2018 FIFA Football World Cup. Despite the charm offensive of David Cameron, David Beckham and Prince William, it was all too late to change the minds of the FIFA Executive Committee members. Most of them had already decided whom they were going to vote for. Trying to change their minds in the last few days was always going to be an uphill struggle, with the added risk that they would perceive it as a sign of desperation.

STRUCTURING YOUR PITCH

Having decided who’s going to present, you need to structure the formal, standup presentation. Here’s my anatomy of a competitive pitch:

1. A powerful opening.

2. Brief introduction of your team and their proposed roles on the assignment.

3. Brief re-statement of the client’s needs, goals, issues or challenges.

4. Your proposed solution and its benefits to the client.

5. (optional) Brief credentials, e.g. where you’ve done this before and the results you achieved for the client.

6. Summary and close.

Let’s dissect each section.

1. The opening.

Usually the job of the team leader, how you open your pitch is vital. Some say this is the most important part, as it sets the scene and the tone, and grabs the audience’s attention. If you lose the client early on, you may never get them back. Consider a story, quote, statistic or physical prop.

A THUMPING GOOD OPENING

One of the most striking pitch openers I’ve ever seen was by an engineering company. Led by their MD, the team entered the room carrying a large iron anvil, with a gold plaque on its plinth. They lowered it carefully and silently onto a felt mat laid across the mahogany boardroom table. The client was spellbound.

The MD of the bidding company, an imposing man, laid his hands on top of the anvil, made deliberate eye contact with each member of the client panel and said, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, we won this last year for being the most innovative small engineering company in the UK. Please allow me to introduce my team.’ Their presentation was slick, the Q&A well prepared, and they won the contract.

2. Team introduction.

Either you can introduce your team, or even better, let each person introduce themselves. That gives them airtime and gets them involved in the pitch quickly. Your mission should be to get to sections 3 and 4 as quickly as possible, so this section needs to be snappy. Learn it off by heart.

3. Re-statement of the client’s needs, goals, issues or challenges.

Again, this needs to be non-controversial, brief and succinct. The reason this section of your pitch is important is that it sets the scene for your solution, especially for anyone on the panel who either hasn’t read your bid document or has entered the process late. Assume the client has not read your document cover to cover.

4. Your proposed solution.

This is the guts of your pitch, your value proposition, and where you need to spend most of your time. This should include your approach (expressed in a ‘killer slide’), roles and responsibilities, outcomes, outputs, benefits to the client, and price. Here you answer the client’s question, ‘What’s in it for me?’ Link the benefits closely to the price, i.e. ‘This is what you pay and this is what you get for that investment’.

5. Your credentials.

The reason I think this is optional is because it takes time away from section 4, your proposed solution. If you do a good enough job presenting it, that in itself will ‘credentialize’ you. It’s unlikely the client will have invited you to pitch if they didn’t think you could do the job. So if you’re pushed for time and you’re looking for stuff to cut, cut this.

6. The ending.

The task of closing and summarizing the pitch often falls to the team leader, i.e. they top and tail the formal presentation. If in doubt, recap all the juicy benefits the client will get if they appoint you. Answer their ‘WIIFM?’ question and remind them how badly you want to be the organization that delivers those benefits. Don’t be afraid to ask for the business.

THE ‘KILLER’ IDEA

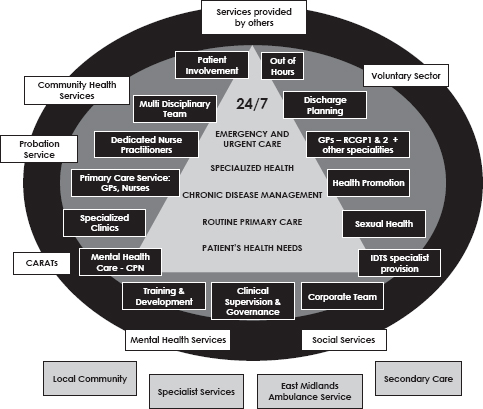

Every new business pitch should have what I call a ‘killer idea’ or ‘Big Idea’ – usually a graphic – that encapsulates your value proposition, especially for a complex service. This anchors and unifies your pitch, allowing your speakers to refer to it and illustrate their individual role in its delivery. I spoke at length about this in Principle 3: ‘Meet the Client Pre-Submission’: this is the initial service model or outline concept that you test with the client in your pre-submission meetings.

Here’s one used by a healthcare provider in a pitch to Her Majesty’s Prison Service for prisoner medical services in a region of the UK:

Don’t worry too much about the detail, but suffice to say that the centre of the graphic shows their core services, with 24/7 medical cover for prisoners at the apex. The boxes surrounding the pyramid represent various elements of the service and key stakeholders, while the white boxes on the outer edge are the broader supporting organizations, such as mental health and social services.

The bid team and I spent half a day together building this graphic. In their pitch, the graphic formed the core of their presentation and the major talking point in the Q&A. It unified, clarified and summarized their proposition to the client.

A PICTURE IS WORTH A THOUSAND WORDS

To quote another example from the bid to host the 2018 FIFA Football World Cup, the client, FIFA, stated that they wanted to open up new frontiers in world football. The self-proclaimed ‘home of football’ – England – is clearly not a new frontier.

One of the slides in Russia’s presentation, the eventual winner of the bid, was a map of Europe, with a line separating Russia from western Europe. To the left of the line were all the venues of previous World Cups; to the right, nothing.

One simple graphic conveyed Russia’s entire message, which chimed with the client’s own objective.

DESIGNING AND PRACTISING YOUR PITCH: FOUR STEPS

Having structured your pitch (i.e. you know who is presenting and in what order), you now need to design it and practise delivering it. This happens in four steps:

1. The design walk-through

2. First rehearsal

3. Dress rehearsal

4. Final dress rehearsal

Scheduling and coordinating these meetings usually falls to the bid manager. They book the rehearsal room and schedule rehearsal time in everyone’s diaries, making sure everyone turns up and every presenter goes through their piece. Though this is rare, some bid managers also act as a presentation coach.

1. Design walk-through

Having agreed who will present and in what order, get together with your fellow presenters and walk through the likely content in the form of scribbled presentations, notes or draft slides. Agree the main messages, overall running order and approximate timing. Start designing the pitch.

If you’ve submitted a bid document as part of the process, identifying your key messages should be easy. If not, you’ll need to spend much more time agreeing and refining those as section 4 of your pitch, your proposed solution. Developing those themes or messages may call for more research, which in turn could affect the design.

Besides the presenters, other stakeholders could be involved in this meeting, to pitch in their views on content and style.

The theatre or cinema analogy to this meeting is the read-through. The actors and director read from the script and discuss the main themes of each speech or scene. This may include the choreography, i.e. where the actors begin and end physically and emotionally, sometimes referred to as the ‘arc’ of a scene.

Each presenter should leave the design walk-through with homework: to develop his/her slides ready for the First Rehearsal.

2. First Rehearsal

If everyone has done their homework, you will all re-convene with more developed slides. You know more or less what you want to say, but it’s still rough around the edges. You half-present, half-walk through your slides, depending on your level of confidence, and you use the input of your colleagues to help you refine them further. But your focus is still on your own individual bit, rather than the pitch as a whole.

If at this stage you’re struggling to clarify what you mean or to define a clear message, my advice is always the same: write it down or say it as if you were talking to your best friend. Expressing a thought or idea in writing forces you to clarify it: you’re literally putting it in black and white. Or buddy up with a team member and explain to them in conversational language what you mean. Verbalizing in simple language will help you distil your ideas.

3. Dress rehearsal

This rehearsal is where it all starts to come together. By now, you and your fellow presenters should be totally familiar with your piece. With the stopwatch on, you run through the whole pitch several times with your slides, visual aids and props, and assess it as a team. Typically at this stage you’ll be fine-tuning your presentations and the words/graphics on the slides, shaving off a few seconds here, adding a few more there.

In this rehearsal, teams tend to make a gear change and focus on making the handovers seamless and the timing precise. Make sure that the top and tail of your pitch are clear, concise and compelling.

By now, you should be able to capture the structure, messages and timings of your pitch like this:

SPEAKER |

MESSAGES |

TIME |

TIM |

We understand you and your issues Introduce team and roles (briefly). S ay how each will speak a little about each area. Overview of the business: - achieved a lot - where they see themselves - mention of factory visit and drop some names of our staff and their staff - key audit requirements and tax considerations - considering them as a listed company - how our role fits their evolving needs |

4 mins |

FIONA |

Continuity, familiarity and she’s got it planned and controlled Priority tasks to concentrate on: - Getting things going immediately, incorporating the planning for listed status - Refer to areas and people like they are neighbours and colleagues - R efer specifically to controls/systems we know and how we can immediately contribute - We are in an excellent position to audit the opening balance sheet and prepare for the flotation as we proceed with the audit |

4 mins |

JOHN |

We know (your) factories - Observations on the factories - Parallels with another situation and the benefits that can be produced (very brief) |

4 mins |

RICHARD |

We know flotations from the MBO point of view and understand your perspective - Key issues facing them with specifics about the company (briefly) - War story emphasizing the role of early planning, keys to success and how they achieved high value - Offer reference |

5 mins |

TIM |

We are the team that knows you and can guide you into the future Summary points: - an audit where you know us and can rely on our knowledge and well-managed coordination - Tim is a hands-on, in-touch partner with commercial insight into evolving issues of a developing business - can identify time and relevance for specialist input - accounting issues related to listed status addressed early and systematically - working with you on operational efficiency, preparing for a successful flotation We look forward to discussing your views and clarifying any points |

3 mins |

|

TOTAL |

20 mins |

If steps 1 and 2 are about creating the jigsaw pieces, step 3 is about putting them all together.

4. Final dress rehearsal

This is where the magic happens.

Every presenter should know their material so well that they have internalized it; it’s become part of them. Here physical actions and words become inextricably linked, individual presenters transcend their own content, see beyond their own particular role… and become a team. This is when the pitch gains an impact beyond the sum of its parts.

In my experience, this is also where a decisive shift in mindset can take place: the team moves from being bidder-centric to being buyer-centric. They start using the magic words ‘you’ and ‘your’ more than ‘I’, ‘we’ or ‘us’. Their emotional and intellectual focus moves from themselves to the client. And that can take a pitch from good to great.

When designing your pitch, limit the number of ideas

Another word of advice when you’re designing your pitch: less is more. Just because you’re desperate to win doesn’t mean you have to throw everything at it, including the kitchen sink. Confine each presenter to three or four main ideas; there’s a limit to the amount of information that people can absorb when it’s delivered orally. If you bombard the client with too many ideas, you run the risk of losing them and your main message, particularly if yours is the umpteenth pitch they’ve heard that day.

And remember the power of story: anecdotes, war stories, examples and case studies all bring your proposition alive for the client. Stories humanize dry facts and figures, convey emotion and, if well told, stay long in the memory.

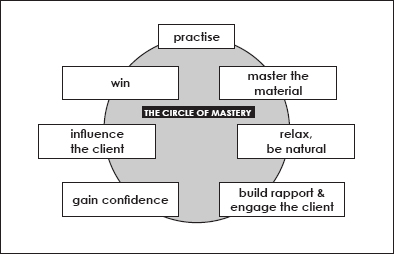

Why is practising so important?

If you want to win, it’s not optional.

By ‘practise’ I mean standing up and delivering your piece, both by yourself in front of the mirror and with your team-mates. Simply reading your notes or slides, either to yourself or in a ‘walk-through’ with your colleagues, will not cut it. Practising the night before won’t cut it. Nor will going through it in the cab on the way there!

There’s no substitute for proper rehearsals well before you’re on.

If you’re in any doubt as to why you should practise, try these benefits for size. Rehearsing allows you to:

• refine your content, both orally and on your slides

• establish the precise running order

• refine your answers in the Q&A

• clarify handovers and timing

• gain confidence

• relax and be natural

• forget yourself and focus on the client

• spot gaps or problems and fix them

The entry point into this virtuous circle is practice.

A gentle warning, however.

Don’t over-practise. In the same way that you can over-stretch a muscle, you can over-rehearse a pitch. You must practise enough to master the material and the choreography of the show, but not so much that you get fed up with it, stale or tired.

Not only must you practise your own individual section of the formal presentation, you must also anticipate the questions likely to come up in the Q&A and your answers (more of that later).

Overcoming nerves with practice

One of the biggest challenges in a pitch is nerves. In my experience, most presenters get nervous because they lack confidence in their content. Practising and mastering your content – spotting things that are unclear or irrelevant and correcting them – turns uncertainty into certainty and boosts confidence.

As a trainer, I present to groups of people all the time and am highly confident. But when I look back to presentations early in my career where I’ve been extremely nervous, without exception it’s been because I’ve lacked confidence in my content. So if you know your stuff and are presenting on that topic, there’s no reason not to be confident.

You will find that the very act of rehearsing your piece forces you to clarify and refine it, in your own head, orally and on the slides. The clearer it is in your head, the clearer it will be when you verbalize it.

But I don’t want you to learn a script that you trot out verbatim: that will render your presentation lifeless and robotic. I want you to be so familiar with your content, the ideas and the order in which you’ll present them that, however your brain spontaneously chooses to express them, they come out clearly and concisely. So, on the day of the pitch, the only prompt you’ll need is a couple of 4 x 6-inch index cards with your notes of the main messages.

Using an external presentation coach

Steps 3 and 4 are also where the right coach or consultant can take your pitch to the next level. They can help you to vary the pace and cadence; turn a good story into a great one; clarify or enliven content that is vague or dull; challenge inappropriate, clichéd or sloppy language; champion plain English (the panel may include lay staff who won’t get the technical jargon); dispense individual coaching to people who know their stuff but are not natural presenters; praise people who are doing well; and tell the senior partner to stop dominating if they want to win!

An external coach who can establish credibility quickly and build rapport with the team brings an objectivity to rehearsals and supports the team with comments, ideas, suggestions and feedback. They can do and say things that most bid managers might not feel able to, due to inexperience, lack of confidence or their relationship with the bid team.

A good external coach can also lay down the law when they need to, e.g. insisting that everyone on the team practise, especially those who don’t think they need to (you know who you are).

I’ve coached senior partners in professional services who thought they could wing it because they’d done so many pitches before and knew what to do. But what message would their absence send to the more junior members of the team? That it’s OK to abandon best practice when you reach a certain level in the firm? And how about building teamwork, mucking in with your more junior colleagues and showing them how it’s done?

The real truth is often that they’re scared of presenting in front of their peers and showing themselves up. What they don’t appreciate is that a leader who’s prepared to reveal some vulnerability to their team gets respect, not scorn.

Slide design

As you’re likely to use PowerPoint in your pitch, it’s worth saying a few words about it.

Several years ago, an MIT study found that 73% of business communication was conducted via PowerPoint. Despite this huge usage, PowerPoint slides tend to be badly designed and presented.

The most common design mistake is what Garr Reynolds describes in his book Presentation Zen (2008) as ‘slideuments’: slides crammed with dense bullet points copied and pasted from a document. The presenter then proceeds to use the slide show as a teleprompt, reading out every word on the slide with their back to the audience.

Not only is this rude, it’s also ineffective. Research from the University of New South Wales (Sweller, 2007) indicates that it’s harder to process information if it’s presented orally and visually at the same time. Reading a list of bullet points out loud from the screen actually inhibits your audience’s ability to digest that information. If you want your audience to read a slide, stop speaking. Take a breath, count to five, then resume.

Slides are a visual aid; they are not your pitch. It’s a cliché, but the most important visual aid in a presentation is the presenter. You should be more interesting than your slides. And you should know your presentation well enough to be able to present without them.

Here are some basic tips on slide design:

![]() Less is more

Less is more

![]() Have no more than six bullet points on a slide

Have no more than six bullet points on a slide

![]() Keep the text of each bullet to six words or fewer

Keep the text of each bullet to six words or fewer

![]() Use more graphics (images, charts, tables, graphs) than words

Use more graphics (images, charts, tables, graphs) than words

![]() Make the graphics simple and clear

Make the graphics simple and clear

![]() Use colour to clarify, not decorate

Use colour to clarify, not decorate

[ STORY: BAD SLIDES CAN KILL ]

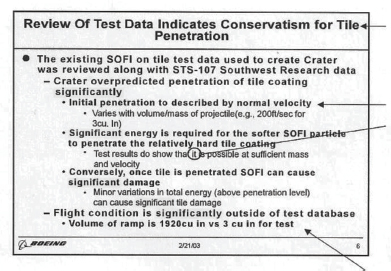

On 1 February 2003, the seven astronauts on board the space shuttle Columbia died when their aircraft disintegrated on re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere.

The cause of the catastrophe was damage sustained during launch when a piece of foam insulation the size of a small briefcase broke off from one of the external tanks. The debris struck the leading edge of the left wing, damaging the tiles of the Shuttle’s Thermal Protection System (TPS), which shields it from the intense heat generated during re-entry.

Could this disaster have been prevented?

According to the findings of an information design expert, a poorly written and overladen PowerPoint slide failed to alert NASA engineers to the danger.

A week before the disaster, a Debris Assessment Team delivered a formal briefing on PowerPoint. While the team warned of the huge risk of debris damage at take-off, the message never got through.

According to information design expert Edward Tufte, Professor Emeritus at Yale, the structure, layout and language of the key slide (shown below) made it nearly impossible to decode the message. Out of 17 fact-filled lines on the slide, the main message was buried at the end:

‘Flight condition is significantly outside of test database

• Volume of ramp is 1920cu in vs 3 cu in for test’

In plain English, this techie-speak means that the debris that struck the wing was 640 times greater than the data used to calibrate the model to predict the tile damage. The model was flawed. And the word ‘significant’ here (an over-used word if ever there was one) means

‘So much damage that everyone dies’

If the slide had been that direct, the seven astronauts might still be alive today.

Taken directly from the Columbia Accident Investigation Board report, here’s the slide that failed to communicate the risk of debris damage at take-off (the arrows point to particularly confusing elements of the slide in Professor Tufte’s analysis):

The title of the slide is misleading: it doesn’t refer to the predicted tile damage, but to the choice of test models used to predict the damage

![]() Six levels of hierarchy created by the bullet points and dashes make it hard to prioritize the information

Six levels of hierarchy created by the bullet points and dashes make it hard to prioritize the information

![]() The vaguely quantitative words ‘significant’ and ‘significantly’ appear five times, each with different meanings

The vaguely quantitative words ‘significant’ and ‘significantly’ appear five times, each with different meanings

![]() The same volume metric (cubic inches) is shown three different ways: 3cu. In, 1920cu in, 3 cu in – in highly technical fields like aerospace engineering, a misplaced decimal point or unit of measurement can have serious repercussions

The same volume metric (cubic inches) is shown three different ways: 3cu. In, 1920cu in, 3 cu in – in highly technical fields like aerospace engineering, a misplaced decimal point or unit of measurement can have serious repercussions

![]() The vague pronoun reference ‘it’ alludes to damage to the protective tiles, which caused the destruction of the Columbia.

The vague pronoun reference ‘it’ alludes to damage to the protective tiles, which caused the destruction of the Columbia.

The high-level NASA engineers tasked with assessing the risk of wing damage were satisfied that the reports – including this slide – indicated that Columbia was not in danger. Tragically, no further action was taken.

IF YOU HAVE TO USE POWERPOINT, USE IT WELL

Here are a few tips for getting the most out of PowerPoint.

When in ‘slideshow’ mode:

![]() For a list of tips: press Fn + F1

For a list of tips: press Fn + F1

![]() To blacken the screen: press the ‘B’ key; press it again to restore the slide

To blacken the screen: press the ‘B’ key; press it again to restore the slide

![]() To whiten the screen: press the ‘W’ key; press it again to restore the slide

To whiten the screen: press the ‘W’ key; press it again to restore the slide

![]() To hide the arrow: press the ‘A’ key; press it again to bring it back

To hide the arrow: press the ‘A’ key; press it again to bring it back

![]() To go to the start or end of your presentation: press the ‘Home’ or ‘End’ keys

To go to the start or end of your presentation: press the ‘Home’ or ‘End’ keys

![]() Number your slides and keep a list handy: if you press a number and ‘Enter’, you’ll immediately go to that slide

Number your slides and keep a list handy: if you press a number and ‘Enter’, you’ll immediately go to that slide

![]() Put a blank slide at the end of your presentation: this will stop the slideshow from reverting to whatever embarrassing picture is on your desktop when you shut it down

Put a blank slide at the end of your presentation: this will stop the slideshow from reverting to whatever embarrassing picture is on your desktop when you shut it down

![]() To toggle between showing the slide only on the computer screen, showing it on both the computer and the big screen, and showing it only on the big screen: press ‘Fn’ + F1 or F5 or F7 (depending on your computer brand)

To toggle between showing the slide only on the computer screen, showing it on both the computer and the big screen, and showing it only on the big screen: press ‘Fn’ + F1 or F5 or F7 (depending on your computer brand)

![]() To select an object, picture or text, or add a hyperlink to another slide, presentation or website: press ‘Ctrl’ + K

To select an object, picture or text, or add a hyperlink to another slide, presentation or website: press ‘Ctrl’ + K

![]() To end the slideshow: press ‘Esc’.

To end the slideshow: press ‘Esc’.

AN ALTERNATIVE TO SLIDES?

Just because millions of people around the world resort to slides (usually PowerPoint) doesn’t mean you have to. I’ve known buyers to heave a sigh of relief when a bidder has asked them if it would be OK not to use PowerPoint in their presentation (we’ve all suffered ‘death by PowerPoint’ at least once in our careers, and once is enough).

A viable alternative to slides is flipcharts.

Akin to storyboards much used in advertising and media, I’ve seen flipcharts used in a pitch, with a combination of pre-prepared and ‘improvised/spontaneous’ flips seemingly produced on the fly – though, in reality, well practised – to illustrate key points.

This bold alternative to slides only works, however, if you practise producing and presenting them, as you would with any presentation. Otherwise they can appear ‘home-made’ and amateurish.

Slides, storyboards, flipcharts – they are all only visual aids to support your messages. They are not the messages themselves. If your content is irrelevant, generic or dull, your mode of communication is immaterial. Fancy delivery won’t hide rubbish content.

PREPPING THE Q&A

We established a few pages back that this part of the pitch can account for up to 75% of the client’s final decision.

Prepping this session means anticipating the likeliest and toughest questions, building the best possible answers, deciding which member(s) of your team should answer them and practising giving those answers.

Everybody on the team must be clear about what type of questions they can or should answer in the Q&A session, as well as who may give a secondary or back-up answer in those question areas, where necessary.

This gives team members equal airtime and reduces the chances of one person dominating. It also demonstrates to the client that team members are knowledgeable on subjects outside their primary area. Finally, it underlines teamwork by ensuring that some questions are answered by more than one person.

As with the formal presentation, this is not about learning answers by rote. It’s about driving clarity into who answers which types of question and how best to answer them.

ANTICIPATE 90% OF THE CLIENT’S QUESTIONS

We know that the most common questions fit the five roles of the buying group described earlier, i.e. strategic, commercial, operational, technical, and pragmatic/price-based.

Strategic questions may be about your vision for the client’s organization, the extent of your ambition for them, their strengths and weaknesses, how you see the market developing and why, the competition and the biggest threats to the client. A good way of prepping strategic questions is to do a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) analysis on the client: this will cover most of the likely angles of attack and impress The Boss that you’ve done your homework.

Commercial questions will focus on price and its relationship with the benefits offered, possible discounts, the likely return on investment, value over the whole contract lifetime, likely payback period and profitability.

Operational questions centre on how your product or service will be delivered and used, how it will fit in with existing programmes or services, and how, where and when client staff will experience it.

Technical questions will tend to look more deeply at how the product works, its specification, dimensions, supply, modifications, models, ‘future-proofability’.Pragmatic questions are often the 10% that we struggle to anticipate, and therefore the hardest to deal with. Often posed by The Guide/The Enforcer, who may be trying to impress The Boss, these questions come out of left field and aim to throw you. They range from ‘What distinguishes you from the other bidders?’ and ‘Why should we appoint you?’ to a pointed question to a junior team member on a point of detail. If they find a weakness in your presentation, they’ll go for you. Think of them as a bloodhound.

And if The Guide is from Procurement, you can be pretty sure that they will question you on price/cost, discounts and value for money.

LOGISTICS AND PREPARATION

HANDOUTS: WHEN TO HAND THEM OUT?

Most clients will expect some form of documentation at the pitch, at the very least a copy of your slides in the form of a slide booklet. The big debate is when to hand it out: at the start or at the end?

My firm advice on this is at the start, for the main reason that the client can make notes on the relevant slide pages as you deliver the presentation. I’ve seen clients receiving a so-called ‘leave-behind’ at the end complain that they weren’t given it at the beginning, for that very reason.

I know you may be concerned that handing it out up-front encourages them to flick ahead to the price slide. Let them do that; you can’t exactly stop them, can you? But indulge them for a few seconds, then contract with them up-front to take questions at the end and bring them gently back to slide 1 by holding up a copy of the handout open on that page.

Most clients are happy when they hear that you’re only going to present for 20 minutes and then answer their questions for the remaining 40. They know they’re going to be able to ask all the tough questions – what they don’t know is that you’ve anticipated them and prepped your answers!

SEATING AND OTHER LOGISTICS

I said earlier that a good pitch has a clear choreography: everyone knows what they’re meant to be doing and when. And that includes who sits where and why. Here’s a salutary tale for how little things unheeded can trip you up:

[ A SEDENTARY TALE ]

I once sat on the client side as a Guide/Enforcer reviewing pitches for a training contract. The presentation room was nice enough, but slightly cramped as there were too many tables and chairs in it from a previous meeting.

One of the bidding favourites came in to present. The team of five filed in full of confidence and brio and approached the table they were to present from, which had the standard bottles of mineral water and glasses neatly placed across it, with a data projector centre-stage.

Unfortunately, because the gap between the table and the wall behind it was quite small, they had little room to manoeuvre. It wouldn’t have been a problem if they’d been clear about who was sitting where. But they weren’t.

The MD sat down rather thoughtlessly in the middle seat, forcing his colleagues to negotiate the wafer-thin space between him and the wall, two of whom went for the same seat at exactly the same time. One of them lost his footing, stumbled and, reaching out for support in an increasingly unstable world, crashed into the table, sending bottles, glasses and water flying over pads, notes and slide booklets. Oops.

On the other side of the room we sat back and watched the disaster unfold, half-horrified, half-amused at their self-destruction. In a nano-second our perception of them and their likely appointment had changed.

Clearly thrown, their confidence visibly draining away and the MD looking as if he was having an out-of-body experience, they’d lost before they’d even begun.

The take-home message is clear: agree in advance who’s going to sit where. Instinct may tell you that your bid leader always sits in the centre of the team. Why not be bold and let them sit to the side or on the edge? From their role on the day it will still be apparent to the client that he or she is the leader, but it might also send the client a subtle message about humility and self-effacement.

When it comes to more junior members of the team, avoid placing them on the edge or to the side. That may make them look (and feel) forgotten or under-valued. Show that they are integrated in the team by putting them in or near the centre. And colleagues who will work together on the contract should probably sit together.

“If they can’t manage a harmonious presentation, would we trust them with our worldwide audit?”

An multinational client

But seating is far from the only thing that can go wrong.

What do you do if the data projector blows up, or the bulb goes? You either take a spare, or you’re so well prepared you’re happy to present without slides (another reason for having a slide booklet).

What happens if the client has positioned you in the room miles from the nearest power point? You bring an extension lead.

What happens if you’re presenting overseas? You make sure you take an international plug adapter.

If you’re presenting a long way from the office and your slot is first thing in the morning, you have a choice: you can go up the night before, or catch an early train or flight on the day of the pitch. But if that train/plane is delayed, you run the risk of arriving at the pitch anxious, breathless and sweaty. Not a great start. And if you miss the train/plane altogether, you’re stuffed. All those long hours and midnight oil will have been for nought.

Being prepared logistically is about controlling your environment. If possible, ask the client if you can see in advance the room you’ll be presenting in, i.e. ‘recce the venue’. Sketch or photograph the room; note where the plugs, doors and windows are; think about the best position for the data projector and screen (if you bring your own); ask if an IT/technical expert will be on hand.

Why is all this prep so important?

Because the more of this stuff you’ve squared away and dealt with, the more of your mental and physical energy you can devote to your content. And the better you know your content, the more you can focus on the people who really matter – the client panel.

DELIVERING YOUR WINNING PRESENTATION AND HANDLING THE Q&A

It’s the day of the pitch, and you know what? Most of the hard work is already done.

If you’ve put in the hard yards up-front, you should be feeling confident and relaxed, as well as alert and ready for action. You should know your own and your colleagues’ presentations inside out; you’ve been put through your paces by panel reviews and rehearsals; you’re clear about what sort of questions to expect and which ones to answer; you’ve got confidence in your team-mates and in your value proposition. What’s to fear?

The only things that can go wrong are:

![]() it’s a done deal with another bidder and always has been

it’s a done deal with another bidder and always has been

![]() the client brings in a new panel member whom you don’t know

the client brings in a new panel member whom you don’t know

![]() the client moves the goal-posts on price, spec or staffing needs

the client moves the goal-posts on price, spec or staffing needs

![]() your main ally on the panel (your ‘friend at court’) is called away to an urgent meeting and misses your pitch.

your main ally on the panel (your ‘friend at court’) is called away to an urgent meeting and misses your pitch.

Everything in this list is out of your control or circle of influence, so why worry?

I’m not advocating sashaying into the pitch with a feather boa, a bottle of Bollinger and a cavalier attitude that suggests to the client you think you’ve already won it. No, you must be absolutely professional and disciplined. But the main reason you and your team-mates have spent valuable time prepping is to give the client a pitch that will blow them away and do it in a way that allows your natural personality and enthusiasm to come through.

In the white heat of a competitive pitch – provided you tick all the client’s commercial and technical boxes – it’s the soft stuff that sways the decision-makers. Rapport, empathy, chemistry, excitement and enthusiasm turn a proficient pitch into a powerful one.

Let’s examine the personal/psychological aspect a bit closer.

A pitch is a high-energy experience, or should be, so make sure you sleep well the night before. It also pays dividends to warm your body and your voice before the pitch. Do some gentle stretches, roll your shoulders, swing your arms, touch your toes, take three or four deep, relaxing breaths. Relaxing physically will help you to relax mentally.

As for your voice, just google ‘vocal exercises’ for some helpful suggestions. These include rolling your tongue around the inside of your mouth several times, sticking it out vigorously and whipping it back in, chanting mantras and tongue-twisters, and trying to kiss your ear (try it, you’ll see what I mean).

If you have properly warmed up, when you stand up to speak you will sound confident and warm, rather than squeaky or reedy. Your voice box will be relaxed and open, not constricted. And you will come across to the client as calm, grounded and friendly, but authoritative and credible too.

In terms of your state of mind, you need to strike a balance between being relaxed and on your mettle, alert but not anxious, professional but not aloof or distant, engaged but not frenetic. Your performance must be stagemanaged, yet with room to be spontaneous.

So although the formal presentation is orchestrated – to enable you to deliver your key messages in the limited time available – the delivery mustn’t be robotic or over-scripted. That’s why earlier on I recommended being clear about your messages, but not learning your presentation by heart or, worse still, reading out loud from a script.

When you are presenting, you should know your slides so well that you only need to glance either at the screen or the laptop to check that the right slide is being projected. Then, making eye contact with everyone on the client panel, you can speak directly to them, needing to look only occasionally at your notes, if at all.

TO TOGGLE OR NOT TO TOGGLE, THAT IS THE QUESTION

While on the subject, there are different views about whether to show the slide both on your computer screen and on the big screen when presenting. Some say that keeping your computer screen blank stops you being tempted to look at it too often, but I think it encourages just the sort of behaviour I’ve decried, i.e. arching your neck to look at the big screen.

I think you should show the slide on both screens (toggle to ‘duplicate’ via the F1, F5 or F7 key). The advantage is that, when necessary, you can check what’s being projected or read out a quote on the slide while still facing the audience, rather than turning your head and face away from them to look up at the big screen.

Whether you’re single-screen or duplicate, you need to be more interesting than your slides.

LISTENING SUPPORTIVELY

When one of your colleagues is presenting, listen actively to what they are saying, as if you were hearing it for the first time. Unfortunately, when someone’s attention is elsewhere, it’s obvious. There’s nothing more offputting than seeing a team member mentally drifting off to a distant planet or prepping their own presentation when a colleague is centre-stage. It’s unprofessional and rude not to give them your full attention. And if I’m the client, that tells me that you left prepping your bit till the last minute or that you’re not a team player, both of which I’ll mark you down for.

If you’re not interested in what they’re saying, why should the client be?

The other risk of switching off once you’ve done your bit is that you fail to spot a concern or problem among the client panel. This might be a look of puzzlement, confusion or boredom, which you and your team-mates need to be alert to. When you’re prepping, this is something you as a team must agree a policy on in advance: do you stop the presentation and ask the client if everything is OK, but run the risk of throwing your timings out? Or do you wait till the Q&A and remember to check with the client then?

My advice is that if you pick up concern during the presentation, stop presenting and deal with it there and then. If you don’t, the risk is that you lose the client’s attention because they’re pondering something you said five minutes ago. And if it’s a minor concern, most reasonable people will tell you to continue your presentation and then raise it in the Q&A.

HANDLING THE Q&A

When it comes to the Q&A, there should be very few hard questions you can’t handle. My only advice is this: do not react defensively to tough or aggressive questions. Never get flustered and don’t take it personally. The panel are just doing their job and stress-testing you. Rather, welcome the tough questions as a platform for showcasing your experience and expertise.

If you’ve ever watched the BBC programme ‘Dragon’s Den’, the most successful entrepreneurs who get investment for their product adopt exactly that approach in answering the hardest questions. Showing you can keep your cool and that you know your stuff inside out will impress.

“They fielded the questions extremely well. They didn’t take them as threats, but as an opportunity to demonstrate what they could do…”

A manufacturing client

DEBRIEF: MY ADVICE

Have one.

A couple of days after delivery but before you get the result from the client, get together as a team to review your performance. It’ll still be fresh in your mind and your perception of it won’t be tainted by the result.

Kick off by setting some ground rules around feedback. For instance, if views are expressed on individual performances, those comments must give the recipient evidence and information that they can apply to their next pitch.

It serves no purpose – and indeed can damage confidence and relationships – to judge a team member, especially if they already feel bad about their performance. ‘I just don’t like your presenting style’ is destructive feedback that helps no-one. There’s little the recipient can usefully do with that information.

My advice for holding a good debrief is to follow the traditional ‘sandwich’ approach in this order: begin with the positive ![]() share the negative

share the negative ![]() remind the group of the positive, i.e. end on an upbeat note.

remind the group of the positive, i.e. end on an upbeat note.

The positive question is straightforward: ‘What went well and why?’ But don’t gloss over the positive just because you’re itching to get stuck into the negative. For example, confining your assessment to ‘David, you did a good job’ is too generic and superficial. What specific observable behaviour did David exhibit that made his performance good? How could the rest of the team emulate David to improve their own performances? Make every member of the team feel good about themselves and their contribution.

As for sharing the negative, if there is any, an obvious question is ‘What would you do differently next time and why?’ Ask the team to assess its own performance, then give each team member the chance to assess themselves, if moved to do so. It often helps if the team captain starts this process.

When assessing the overall team performance, there’s one key question that must be asked: ‘Did we as a team do our absolute best to win this?’

Close the debrief with a reminder of what each individual did well. The beauty parade is a tough call on people who may already be extremely busy with their ‘day-job’. If you need to call on them again for another pitch, you want them committed to and energized about it, not going through the motions or resistant. So, even if you didn’t get the business, make them feel good about their involvement.

I’ve seen a nice way of doing this. Focusing on one individual at a time, get everyone else on the team to write one positive thing anonymously about them on a post-it note. Gather them all up and give all the post-its to that person. Then move on to the next individual and so on, until every team member has a tidy pile of positive comments. I’ve known people to treasure this physical feedback throughout their careers.

Having held the debrief, if you then hear that you have won the contract, go out and celebrate! If not, at least you will have learnt from the experience. In your next pitch, you’ll know what to do differently to shorten the odds of winning.

LET’S BUST SOME MYTHS

A lot of people have fixed ideas about how to pitch and present. I’d like to explode three of the most common ones:

BIG FAT MYTH #1: LOOKS MATTER.

Unless you’re pitching for a model agency contract, this delusion encourages bid leaders to pick presenters who are good-looking but who may not be the logical or appropriate choice for that particular contract or client. I’ve never known a supplier to be appointed or rejected on the basis of physical looks.

Physical presentation and demeanour are different, however. This is about being well dressed and presentable, and adopting a body language that conveys professionalism and confidence to the client when you walk into the room.

An American client of mine is ex-military and always well turned out. He was once involved in a pitch to the US Department of Defense in Washington, which he and his team won. When he got to know the main decision-maker during delivery of the contract, the client – also ex-military – told him that of all the bidders’ shoes, his were the cleanest!

The take-home message is: whether you like it or not, you’re being judged, so be as presentable as possible.

BIG FAT MYTH #2: NERVES ARE BAD.

First of all, don’t worry if you’re nervous before a pitch. In fact, worry if you’re not.

Nerves are only bad if you let them cripple or paralyze you. Top performers in any field will tell you that you need some nerves. Those butterflies in the pit of your stomach tell your body and brain that you are about to perform and prime you for mental or physical exertion.

So don’t waste your energy trying to suppress any nervous feelings. Accept them, go with them, and if you can, turn them into excitement and anticipation. That will raise your energy levels when you come to present.

Slow, deep breaths and gentle physical exercise on the morning of the pitch can help. But in my experience, the best remedy is to accept nerves as part of the territory, rather than resist them.

BIG FAT MYTH #3: ONLY CHARISMATIC PEOPLE PRESENT WELL.

Clients have told me time and again that what they seek in their suppliers and advisors is honest people who know their stuff and who are genuinely interested in and ambitious for their business. In fact, some clients are downright suspicious of ultra-smooth, slick, charismatic presenters – especially if their own presentational style is light-years away from that.

While very few people have a room-shaking aura (I’m told that Bill Clinton does), you do need to make an impact on the client. You need presence. Contrary to popular belief, anyone can have presence because it comes from desire.

‘Presence’ is simply wanting to be there.

If you’d rather be somewhere else or are secretly hoping that the ground will open up before it’s your turn to present, you won’t have much presence because mentally and spiritually you won’t be present. But if you’re gagging to affect the client and their organization, to blow their socks off with your presentation and ideas, and can’t wait to take their questions, you’ll have undeniable presence.

WINNER TAKES ALL BOTTOM LINE:

While the bid document is essentially an intellectual exercise, the pitch involves verbal and non-verbal communication, giving clients an experiential understanding of what you’ll be like to work with. So, for that brief but intense hour, you and your colleagues must wield all three weapons of persuasion: credibility, logic and passion.

[ FOOD FOR THOUGHT ]

Review your latest pitch against the list below. Did you do the Dos and avoid the Don’ts?

DO |

DON’T |

Prep the q&A thoroughly |

Let one person dominate |

Rehearse individually and collectively |

React defensively to tough questions |

Turn your features into benefits via ‘So what?’ |

Talk too much about yourself |

Build a killer slide that summarizes your value proposition or service model |

Bombard the client with too many ideas |

Let your personality come through |

Bore them |

Show enthusiasm |

Think you can wing it |

Recce the venue, if you can |

Neglect any member of the panel |

Bring your proposition alive with stories, quotes, physical props |

Disengage when the rest of your team are presenting |

Ask for the business – and mean it |

Assume you’ve won |

In your next pitch, what could you do more of, less of or stop doing altogether to raise your odds of winning? Give that some thought and note your ideas in the table below:

Do more of |

|

Do less of |

|

Stop doing altogether |

|

See you over the page at ‘Principle 6: ‘Get client feedback post-award’.