PRINCIPLE

FOUR

PERSUADE THROUGH

THE WRITTEN WORD

ChAPTER SUMMARY

1. The purpose of the bid document.

2. How to include the right content.

3. How to structure and design your bid response.

4. How to use the written word to win.

In the many years I’ve spent reviewing and supporting proposals, few have blown me away with their clarity, conciseness and overall impact. Most bid documents are badly written. That’s great for me, as it represents a huge market for my writing training programmes. But it’s not such good news for clients, buyers or bid evaluators.

WHAT’S THE BID DOCUMENT OR PROPOSAL FOR?

In proposals best practice, the purpose of the document is to capture and build on what you covered in your meetings with the client (see Principle 3) and get you shortlisted for the oral presentation (or ‘beauty parade’), if there is one. If there isn’t, clearly it’s to win the bid by giving the client a solution to their problem in a way and at a price that offers greater value over the lifetime of the contract than any other bidder.

But most bid documents fail for reasons of content, structure or language – and sometimes all three.

INCLUDING THE RIGHT CONTENT

The content or substance of your bid document will depend on the contract you’re bidding for and your particular area of expertise. Sadly, I can’t help you with that; it’s context-specific. However, I can help you with certain types of content that every bid or proposal should contain.

The first principle is to give the buyer the content they ask for in the RFP/ITT, i.e. to comply with their instructions.

Remember when you were at school and your teachers told you in the exam to ‘answer the question’? Bids are no different.

When you’re responding to a prescriptive RFP or ITT that gives clear instructions on the structure of your response or how to submit it (common in public sector bids), do as they say. An obvious example is the instruction to keep your answers within a specified word limit; if you exceed that limit, you’re giving them an easy reason to disqualify you.

Follow their instructions to the letter. They want to make it as easy for themselves as possible to evaluate all the bidders’ responses against the selection criteria and reach a decision.

I once audited a submission for a client. They hadn’t followed all the response instructions, had skipped some required sections and added others not asked for. Their proposal was non-compliant and promptly disqualified by the buying organization.

As the Head of Procurement at a large local authority once said to me:

“Read the question and answer it. If I ask you for evidence of workforce diversity, don’t give me three lines and complain when I mark you down for that. Give me chapter and verse, demonstrating your diversity and showing me that you live by that value when you recruit and develop your staff.”

A good tip here is to do what every professional writer does: read the question out loud (ROL).

ROL slows you down by forcing you to say every word, giving your brain time to process and analyze the text. This helps you to understand what the question is driving at and how best to answer it, picking up key words like ‘should’, ‘must’ and ‘require’.

(ROL is also a great technique for checking your written answers, but I deal with that later in this chapter under editing and checking.)

GETTING CONTENT RIGHT HAS A LOT

TO DO WITH MINDSET

Most bid documents are dull.

A number of years ago, I worked with an experienced recruitment consultant. After evaluating over 200 bid documents for clients, Stephen finally threw the towel in, despite the fact that the role was lucrative. Why? He couldn’t hack the boredom any more. When he started to lose the will to live by page 3 of a proposal, he realized enough was enough.

A TV documentary on how scientific grants are awarded concluded that, no matter how academically or scientifically worthy the application was, it had to excite the evaluators to win. Serious doesn’t have to mean dull.

What makes most bids dull? Answer: they talk more about themselves than the client. The mindset of the author(s) is bidder-centric, not buyer-centric.

WHAT MANY BID WRITERS THINK THE CLIENT

IS INTERESTED IN

1. THE BIDDER’S STATE OF MIND.

‘We are delighted to be able to respond to your invitation to tender...’ or ‘We are pleased to submit our response...’

2. STATEMENTS ABOUT THE CLIENT’S INDUSTRY OR ROLE THAT DON’T TELL THEM ANYTHING NEW.

‘As a finance director, you need to cut costs and deliver shareholder value...’ or ‘Recent years have witnessed an increase in the use of Lean Process Improvement...’

3. INFORMATION ABOUT THE BIDDING COMPANY.

‘We were founded in 1915 and have grown organically since then...’ or ‘We have completely redesigned our website...’

THREE THINGS THE CLIENT IS INTERESTED IN

1. Themselves.

2. Er...

3. That’s it.

Not understanding the buyer’s locus of interest sets you up to fail, by generating problems with content (and structure). Bidder-centric documents tend to:

• adopt the Super-Smashing-Great school of writing, so everything they do is unique, exciting, innovative, leading edge, best-of-breed, world-class, unparalleled

• list the features of their product or service, but don’t convert them into benefits for the client

• delay or bury the client benefits in the verbiage of their document, so the client misses them

• fail to bring the client benefits alive for the reader with examples, i.e. they tell more than they show.

Weak bids talk more about what they’ve done and are going to do than what the client is going to get. If you want to excite the reader, appeal to their self-interest by talking about what they’re going to get, i.e. the benefits for them of awarding you the contract.

Here’s an example of what I mean, from a law firm’s proposal:

CONTENTS

Executive summary |

2 |

Our team and our approach |

4 |

Our project management expertise and resources |

8 |

Our fee proposal |

18 |

Appendix 1: Our supplier service structure |

20 |

Appendix 2: Our value-added services |

21 |

Appendix 3: Our global network |

25 |

No prizes for guessing the mindset of the author. The predominant word in this list of contents is Our.

The writer is clearly more interested in themselves and their own organization than in the client. They are being bidder-centric, not buyer-centric. What would be a better word than our? You or your. But to do that you have to re-write the whole document from the client’s perspective. Show them how your product or service will make their life easier, better, richer, or will deliver the objectives and outcomes they want (translate into the language of your particular sector or opportunity). This is all about benefits, as opposed to advantages and features. Benefits are more persuasive than features.

(NOTE. When reviewing a bid submission, I always look at the table of contents first. It’s like looking at an X-ray of the document: it helps me to see not only the underlying structure of the document, but also the mindset of the author.)

THE POWER OF ‘SO WHAT?’

(OR, HOW TO CONVERT FEATURES INTO BENEFITS)

If benefits are the way to go, let’s first clarify our terms: F.A.B. stands for Features, Advantages, Benefits.

A Feature is a characteristic of a product or service. The client may or may not value it.

An Advantage is what your product/service does that others don’t, i.e. what differentiates it from the competition.

A Benefit is how your product/service makes someone’s life better in a way that they will value. Examples of benefits include:

• Make money

• Save money/time

• Look good in your boss’s eyes

• Get promoted faster

• Live longer

• Sleep like a baby

• Boost shareholder value

• Win more tenders

• Convert more leads into sales

• Get fit

• Be healthy

• Get your dream partner/job/home

• Improve your sex life

• Improve productivity

Trouble is, many bid writers confuse benefits and features, or simply list features without converting them into client benefits. How do we make that conversion? By challenging them with ‘So what?’ Here’s what I mean:

“Hi. I’m from BabyGates.com and we specialize in child safety products.”

[FEATURE]

“So what?”

“We’re the market leader for child safety [feature]. In fact, we’ve won more child safety awards than anybody else [ADVANTAGE] .”

“So what?”

“Well, we’ve just designed a new, deluxe, 21st century baby gate.” [FEATURE]

“So what?”

“It’s easy to install with special gate-style mountings and comes in a range of colours to match your home.” [FEATURES]

“So what?”

‘It comes with a child-proof, tamper-free KiddyGuard.’ [FEATURE]

“So what?”

“That means your child will never push the gate over and fall down the stairs.” [BENEFIT, FINALLY]

When it feels daft, absurd or negligent to ask ‘So what?’, chances are you’ve landed on the end-benefit. This simple little question forces us to drill down from the surface feature to the bedrock benefit.

Now have a go yourself.

Below is a list of features converted into benefits with ‘So what?’ Notice how there are far more words in the Benefits column than in the Features one. That’s a good sign. It shows that we’re going to town on the benefits to the client, rather than just listing the features.

I’m sure you’ve also noticed that when we talk about features, the predominant words are we and our. Yet when we talk about benefits, the predominant words are you and your. Another reason to focus on benefits.

The strongest benefits have three qualities: they are concrete (not abstract or woolly), specific (not generic) and definite (not vague). When you add your own examples in the empty boxes in the table below, try to stick to those qualities.

FEATURE |

|

BENEFIT |

Our firm has 55,000 staff in 20 countries around the world. |

So what? |

You get relevant, practical and current advice on competition law from local people who know the latest regulations and, in some cases, even know the regulators. What that means for you is insight into which of your new products will best satisfy the law in each particular jurisdiction and which ones carry the greatest risks in terms of anti-competitive activity. |

Our journal is peer-reviewed. |

So what? |

You can rely on the content, currency and intellectual rigour of every academic paper in our journal. Not only has it been written by an expert in that particular field, it’s been reviewed by one. Authors know their work will be peer-reviewed and only published when approved by our review panel. So when you subscribe to BioGenetics Gazette, you get to read papers of the highest quality. |

Places on our writing courses are limited to 10. |

So what? |

You see faster improvement in your writing skills. With fewer attendees than other courses [advantage], you get more individual attention and coaching from the trainer, who has more time to address your particular writing needs and goals, and give you one-to-one feedback on your writing sample. Smaller numbers also mean that you get more opportunities to explore your own writing issues in the group discussions and sub-group exercises. So when you get back to the office, you can apply what you have learnt faster and more effectively to your own work. |

|

So what? |

|

|

So what? |

|

|

So what? |

|

WHY ARE BENEFITS MORE POWERFUL THAN FEATURES?

Because benefits appeal to the client’s self-interest. Clients are less interested in what you do and more interested in what they get when they appoint you and work with you. It’s OK to list the features of your product or service, provided you then relate them back to how the client will benefit. As you may have spotted in the table above, a useful phrase for doing that is ‘What that means for you is…’, then list all the benefits that will get them salivating. Alternatively, use the phrase ‘What that allows you to do/get is…’, completing the sentence with benefits.

To sum up, there are three devices for converting features into benefits:

1. ‘So what?’

2.‘What that means for you is…’

3.‘Which allows you to…’

HOW TO GROUP BENEFITS MEANINGFULLY

In Principle 2, we identified the five typical buyer roles in most sales situations. Why not match your benefits to these roles?

THE ROLE |

THE BENEFITS THEY’RE INTERESTED IN |

The Boss |

Strategic, organizational, reputational, commercial (e.g. shareholder value, share options), visionary |

The Money Person |

Financial, ROI, payback, value for money |

The End-User |

Functionality, operational, performance, e.g. reliability, relevance, ease of use |

The Expert |

‘Techie’, e.g. spec, dimensions, product/performance details, modifications, functionality |

The Guide |

Any of the above |

Andy Maslen, my former business partner and co-founder of Write for Results, puts it nicely in his excellent book, Write To Sell, The Ultimate Guide to Great Copywriting: when communicating with prospects or clients, we need to transmit from Radio WIIFM (‘What’s In It For Me?’) rather than Radio WIII (‘What I’m Interested In’). Transmit on their frequency and you get their attention.

Remember: benefits persuade and sell; features and advantages don’t.

STRONG BIDS ARE NOT JUST TAILORED;

THEY’RE PERSONALIZED TO THE CLIENT

We’ve already established that your buyer is more interested in themselves than in you. To excite them, you must tailor your offering to them; generic bids just don’t cut it. But when I say ‘client’, I don’t mean the organization as an abstract concept. I mean the flesh-and-blood decision-makers in that organization, who will evaluate, discuss and score your bid, whom you must get to know as individuals.

We covered this in Principle 3, ‘Meet the client pre-submission’, but it’s worth repeating.

You can’t tailor your bid if you don’t get to know the client, and you can’t get to know them if you don’t meet them. That’s why either knowing them well already or meeting them pre-submission is vital. Personalizing your bid is about understanding the needs and agenda of each individual decisionmaker and addressing those needs in your response.

THE MAGIC WORD(S) AND THE RULE of 3:1

When we talked earlier about converting features into benefits, I mentioned that when we articulate client benefits we naturally use the words you, your and yourself. These are magic words, because they make the reader feel as if we are talking to them as an individual. They satisfy a basic human need to be heard and feel special. Using them liberally is a simple device that is almost impossible to overdo.

And by using these words three times more than I, we, us or our, we force ourselves to talk more about them than us, getting their attention and making them more receptive to our message or argument.

(Grammar geek note: you in this context is the second-person singular, as opposed to the first-person singular, which is I.)

If you have any doubts about the power of this simple word, consider this: if you happened to spot your own name in a biddocument or any communication for that matter, would itmake you more or less likely to read that document? (See how many times I used the Magic Word then: did it make you feel uncomfortable or strange? It works because it’s how we naturally communicate with each other.)

AVOID THE MULTIPLE PERSONALITY DISORDER

When addressing a multiple readership, such as in a bid document, inexperienced writers tend to use ‘you’ in the plural sense (technically known as the ‘second-person plural’). You’ll see this a lot in emails, too. They’ll use phrases like ‘some of you’ or ‘all of you’, as if their readers were huddled around one copy of the document or suffering from a multiple personality disorder.

When you read a document, do you feel like you’re part of a market or a crowd reading it? No, of course you don’t. You feel like you – a unique, special, distinct person – and you want to be addressed that way. Clients are no different.

AROUSE DESIRE THROUGH STORY

In any sales situation, making your buyer want your product or service is vital. Wants are more powerful motivators than needs. My kids don’t need the latest Xbox LIVE game, but believe me, they want it! Ask a woman if they’ve ever bought a pair of shoes they didn’t need, but wanted; most will say ‘yes’. Ask a man if they’ve ever bought a gadget or a tie they didn’t need, but wanted; most will say ‘yes’. (Please forgive the gender stereotypes.)

Why is desire so much more powerful in changing our behaviour than need? Because when we want something (or someone), desire engages us on a deeper emotional level than need, which tends to be more rational. And this relates to the three principles of persuasion identified 2,300 years ago by Aristotle in Ancient Greece: ethos (character or credibility), logos (reason, logic) and pathos (passion or feeling). Aristotle judged that pathos far outweighed the other two in terms of persuasiveness.

The greatest communicators, from Aristotle and Shakespeare to John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, have all agreed on one thing: that logic makes people think, but emotion makes them act.

SO HOW DO WE MAKE BUYERS WANT TO APPOINT US IN A TENDER?

Tell more stories.

Stories are man’s oldest device for informing us, entertaining us and engaging our emotions. They can bring dry information to life through image and imagination, metaphor, drama, surprise, delight. In a bid document, stories take the form of case studies or small examples that demonstrate how your product/service improved a client’s business. And in a pitch, telling an anecdote or ‘war story’ can reinforce a message, demonstrate a brand value or dramatize a benefit. Good stories make a connection with the audience.

Trouble is, most case studies are dull and turgid. This is because they don’t honour the four classic components of any good story. From the Epic of Gilgamesh, carved in cuneiform on clay tablets 4,000 years ago, and the Bible to Shakespeare and War and Peace, to Batman and Lord of the Rings, a good story must have:

1. A protagonist (the hero, main character; can be a team or an organization);

2.A predicament (the protagonist faces a challenging situation with an uncertain outcome);

3.Narrative (plot, setting);

4.A resolution (in overcoming their predicament, the protagonist grows as a character).

Here’s a simple case study that uses all four story elements:

[ ALAN’S STORY ]

Context: Swanswell is a 40-year-old UK charity that helps people who are struggling with substance misuse. It treats over 9,000 people a year and reaches hundreds of thousands online. Alan’s been in treatment with Swanswell since 2004. He stopped using illicit substances some time ago but found coming off his methadone prescription a big challenge.

Before using The Swanswell Recovery Model interventions, Alan had tried to reduce his methadone medication gradually. But he suffered many anxieties about doing this, so the reductions were sporadic and slow. This demotivated him and undermined his confidence in his ability to become medication-free.

Using The Swanswell Recovery Model, Alan and his Swanswell keyworker explored different treatment options. Alan examined his anxieties around reducing, and used the interventions in the model to re-state his recovery goals and boost his confidence to achieve them.

A few months later, supported by his misuse keyworker and GP, Alan successfully completed a community detox. To date, he remains illicit drug-and methadone-free, and has exited drug treatment after eight years.

In this short case study, Alan is the protagonist, his predicament is clear and the narrative relates to the support he got from Swanswell, in the form of the charity’s Recovery Model and the Swanswell keyworker allocated to him. The resolution is how these interventions helped him turn his life around.

What’s interesting about this case study is that although Alan is the ‘hero’, he’d be the first to admit that he couldn’t have achieved the turnaround without Swanswell. So this mini-story casts both characters – Alan and Swanswell – in a heroic light.

AROUSING DESIRE THROUGH SCARCITY

We can also use the scarcity principle to make people want whatever we’ve got or to create a sense of urgency in them to get it.

One of the six universal principles of social influence identified by Robert Cialdini, scarcity says that the less available something is, the more people want it. Rare or unique things hold greater perceived value for us; we want them more when we learn that they are available in limited quantities or for a limited time.

A petrol shortage is a good example. Supply of a useful resource is restricted and demand typically soars with panic buying; the supply/demand equation loses its equilibrium. In that scenario, a resource that many of us take for granted becomes more precious and we may be prepared to pay over the odds to get it. When normal supply resumes, petrol prices tend to return to their previous level.

Concorde is another example of scarcity, but here the ‘resource’ was finite. When British Airways decided in February 2003 to ground the iconic plane after the terrible crash in 2000 over Paris, the sale of seats took off. And when its final flight was announced eight months later, thousands of people blocked a major motorway to say goodbye to the aircraft that they could have seen every single day for the previous 30 years.

HOW CAN YOU USE SCARCITY TO SELL YOUR PRODUCT

OR SERVICE IN A TENDER?

First, you must convince the buyer of its benefits to them. Then, tell them what is rare, unusual or unique about it. I once read in a proposal: “Expertise in this particular area of competition law is rare… and we have most of it.” While that may sound arrogant, they were able to show that it was true, so it became a compelling motivator to the buyer to appoint them.

In a proposal from an oilfield services company offering a new generation of drill technology to an oil and gas client, the author went to town on the benefits of increased rate of penetration, faster production and less ‘red money’ (written-off costs). But the clincher was in the last paragraph of the proposal:

“At the moment there are only five of these drills in the world. Please get back to me by next week to book yours and ensure delivery in time for production on rig XYZ.”

You see, the benefits alone may not be enough to move the buyer to buy. They may still be unsure or scared of acting, so we can use scarcity to counter that inertia. Scarcity can push them to act by inducing a sense of urgency or a fear of missing out on something valuable.

CONVINCE WITH EVIDENCE

Sometimes we need to do even more to push the buyer over the buy-line. They may still need convincing. And the biggest barrier to conviction is their fear of making a mistake – especially in public procurement where they are responsible for spending the public purse wisely.

HOW DO WE REDUCE THEIR FEAR OF MAKING A MISTAKE?

By giving them evidence. We must prove to them that we, our product or our service are as good as we say it is. The most powerful proof is social proof: we are more likely to do something if we see other people like us doing it too.

This is where client quotes, references and testimonials come into their own. Of course we are going to say nice things about ourselves or our service, because we want the business. But if someone outside our organization experiences our service first-hand and says great things about it, that’s much more convincing.

Strong client testimonials have the following features:

• they are attributed to a named individual (otherwise your reader will think you’ve made it up)

• they rave about you, rather than being mildly positive

• they are given by someone who works in the same industry, function or type of organization as the reader (i.e. the reader must be able to identify with them)

For instance, if you’re bidding for a private sector contract and you include only public sector quotes or testimonials in your bid document, your reader is likely to think or feel, ‘You don’t understand me, we don’t operate in a public sector culture here.’ In other words, your testimonials won’t carry any weight with the reader and may count against you.

Besides testimonials, what other evidence can we use in our favour?

A credible track record of delivering similar contracts; statistics; free samples; guarantees; industry awards; positive press coverage; social media ‘likes’ – these also shore up our claims about our product or service. Showing a track record of delivering similar contracts successfully in the client’s industry sends them strong messages:

• ‘We understand the challenges in this type of project, so we can preempt them, saving you time, money and hassle’

• ‘We won’t waste your time (and money) familiarizing ourselves with the terrain’

• ‘We already have the expertise we need to handle your contract, so we won’t outsource it to untried third-parties’

• ‘You won’t be paying us to learn about your industry or sector’

• ‘Our team is ready to start’.

Stats about the reliability or performance of your product or service – compiled by an independent, credible source – also make your buyer feel surer about you. It means they have more sources to believe than just you.

Giving away free samples sends positive messages to the buyer, too. It shows you have confidence in your product. In the case of a service, you can give value in the form of insights, ideas or other information likely to be useful to them. But be careful what you give away: don’t surrender your intellectual property because you’re so desperate to win the bid. They may just run off with it and give it to a competitor.

Willingness to do a small assignment for the buyer free of charge during the bid process is another example of evidence, and not unheard of. If you get the chance to do it, grab it with both hands – provided the job won’t cost you the earth. It’s a golden opportunity to demonstrate your expertise to the buyer. It will also give them insight into what you will be like to work with – a vital factor in their decision.

All of this provision of evidence helps your buyer to believe your claims, which is why another word for evidence is credentials, from the Latin word meaning ‘to believe’. They’ll be convinced it’s safe to buy from you when they believe you.

In sum, we use compelling evidence to help the reader feel that they‘re not making a career-limiting mistake in hiring you. As the cliché has it, ‘No-one got fired for hiring IBM.’ By reducing their perceived risk of buying from you, you make their decision easier to justify, both to themselves and their boss.

To summarize this section on content, it’s about striking an imbalance between stuff about you and stuff about them. Of course, you have to talk about yourself and your organization or team to an extent, but when you do, always relate it back to what it means for them, the client. Place them fairly and squarely at the centre of your bid. Never lead with your agenda; lead with theirs. Talk more about them than you. Talking more about yourself than them will turn them OFF; hearing how you are going to help them will turn them ON.

Be buyer-centric, not bidder-centric.

HOW TO STRUCTURE AND DESIGN YOUR BID RESPONSE

The structure of any document is simply the order or arrangement of the content, i.e. what comes first, second, third, etc. Design is how that content is presented and laid out on the page. Let’s deal with structure first.

Much of the sales communication I come across is structured like this:

EXHIBIT A

Reading left to right, most bid documents or pitches spend the first pages or slides talking about themselves and their organization. They may call it ‘Introduction’, ‘Scene-Setting’, ‘Exposition’ or ‘Contextualization’. I call it ‘guff ’.

The author mistakenly believes that this is of interest to the client; that it will convince them of the bidder’s credentials and encourage them to read on. Trouble is, you’re delaying what they’re most interested in – the benefits to them of hiring you (remember, they’re more interested in themselves than in you). You’re relegating your main message to the end of the document in an argumentational climax or burying it somewhere in the middle (the black crosses).

This approach to organizing your ideas is known as deductive logic, i.e. it leads the reader step-by-step through a linear argument or evidence to the conclusion or main message. There are three risks to this approach:

• the reader loses interest and stops reading before they reach your main message

• the reader loses patience if you put too many ideas in the sequence

• the argument may fall over if the reader disagrees with any step in the sequence.

So, invert your structural pyramid to look like this:

EXHIBIT B

Hit the reader as soon as you reasonably can with your main message – that may be the chief benefit of appointing your firm, your major recommendation, a key finding from a study or the main point of your white paper. If in doubt, lead with the client benefits. Put the stuff about you later in the document once you’ve grabbed and held the reader’s attention with what they are most interested in.

This approach to organizing your ideas is known as inductive logic, i.e. it gives the main message first, followed by the evidence, creating pyramids of ideas. This brings three benefits:

![]() you engage the reader because they get what they’re most interested in first

you engage the reader because they get what they’re most interested in first

![]() they save time by getting the answer early, with the option of reviewing the evidence if/when they want to

they save time by getting the answer early, with the option of reviewing the evidence if/when they want to

![]() your argument doesn’t fall down if the reader disagrees with one of the supporting ideas.

your argument doesn’t fall down if the reader disagrees with one of the supporting ideas.

There’s a cliché that every document must have a beginning, a middle and an end. What we’re doing here is starting with the end. It’s the best way I know of making your client communications more engaging.

INVERT YOUR PYRAMID FOR INDIVIDUAL ANSWERS, TOO

Starting with the end also works when you’re answering individual questions in a pro forma bid response. Give the evaluator a summary outline of your answer first, then expand on it. There are two reasons for doing this:

1. He/she may be satisfied with your summary and not feel the need to read on;

2. The summary gives them the context to grasp and assess the text that follows, making it easy for them to understand the detail.

WHY DOES THIS APPROACH WORK?

I observe many business writers figuratively ‘clearing their throats’ before their writing becomes relevant to the reader. In my writing workshops, I often ask the delegate to identify the first thing in their copy likely to interest their reader – and cut everything above that. ‘Hack the head off your copy!’ I tell them, forcing them to go straight to what will most engage the reader. Cut to the chase. An NHS evaluator in the UK told me recently that if it takes him more than two minutes to find the core of an answer among all the words, he gives up… and marks the client down. Delegates of mine sometimes push back against the inverted pyramid recommendation. They argue that inverting the pyramid gives the game away at once and steals its own thunder.

I usually respond like this.

In the entertainment media, like fiction, theatre or cinema, it makes sense to lead gently into the story, develop the characters over time, weave the various strands of the plot together and hold the climax back until the end. In narrative fiction, that maintains the suspense and keeps the reader or audience guessing. But a business reader facing a significant investment or purchasing decision is in a very different mindset to when they’re reading a novel or watching a movie.

You’re not writing fiction here (at least I hope you’re not). Your job is to give the client/evaluator as much relevant information as possible for them to be able to make an informed buying decision. In the bid document at least, grand reveals or big surprises are likelier to work against you than for you. And the obvious risk of holding your main message back until the end of your argument is that the reader loses interest and gives up before they get there.

WHAT’S THE BEST STRUCTURE FOR A PROPOSAL?

We see the inverted pyramid working in the classic structure of a tender response. If the ITT you are responding to prescribes the structure, as in most public sector pro forma tenders, you have no choice but to comply; doing otherwise will result in a ‘non-compliant’ bid and you’ll be disqualified. If, however, you can respond free-form (i.e. you have control over the structure), then the five-step structure I shared with you in Principle 3 is a gold standard. Here it is again, with a bit more detail:

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Optional, but highly recommended for longer documents. The only part of the document that every member of the client evaluation team will read, regardless of grade or role, this must summarize all the reasons to appoint you, i.e. all the benefits the client will get. The client CEO needs to be able to read this in under three minutes. In fact, I consider the ‘exec summary’ so important I’ve dedicated a separate mini-chapter to it (Principle 4.5).

2. OUR UNDERSTANDING OF YOUR NEEDS/GOALS/

CURRENT SITUATION

A concise description of the client’s major issues, needs or objectives shows that you understand what is driving the tender and how it fits within their wider business strategy. You want the client to say to themselves, ‘Yes, these people really get it’. This section is your platform to introducing and expanding on your proposed solution or ‘value proposition’.

3. OUR PROPOSED SOLUTION TO MEET YOUR NEEDS

This section is the guts of your proposal. It explains/shows how you will address those issues or needs and includes your proposed team, approach, benefits and price. I’m a firm believer in a killer page that encapsulates your entire value proposition or service model, preferably as a graphic with supporting text (see Principle 3, ‘Meet the client pre-submission’).

Include profiles of key team members and why they’ve been chosen for their particular role on the assignment. Don’t hide their standard CVs in an appendix in the back of the document: most appendices don’t get read. Bring tailored versions up-front into this part of the document. And don’t be tempted to tuck the price away at the back of your bid like a mad aunt. Make the link between what the client pays and what they get explicit and clear. Be bold.

4. WHY WE ARE THE RIGHT SUPPLIER FOR YOU

This is a brief presentation of your organization’s credentials, e.g. case studies, testimonials, client references, previous similar jobs and outcomes. This is about convincing the client that you are as good as you say you are: you’re a safe pair of hands for their precious business. And attribute your testimonials; otherwise the client will think you’ve made them up!

5. SUGGESTED NEXT STEPS

Show the client – without presuming you’ve won – that you’ve thought through what needs doing in the first few days or weeks and that you’re ready to hit the ground running. Tell them what they can expect when they start working with you.

Of course, you can play around with the wording of the section titles, incorporating the client’s language or terminology as appropriate. But in essence what you’re doing with this structure is saying: ‘This is our take on your problem; this is how we propose to address it; this is where we’ve done it before and why you can trust us to do it for you; and this is what you can expect when we start.’

Once again, we’re inverting our pyramids at this macro level by frontloading the document with the executive summary (all the benefits the client will get) and our proposed solution for their business or organization. Where we typically talk most about ourselves – in the credentials/’Why us?’ section – is relegated towards the end of the document, as it should be.

GIVING YOUR DOCUMENT IMPACT BY DESIGN,

NOT ACCIDENT

FORMAT: PORTRAIT OR LANDSCAPE?

When I first joined Ernst & Young, all their proposal documents were in portrait. That was how they’d always been done and no-one saw any reason to change. But one day, maybe because we had a bid that needed an unfolding flowchart that the reader could open out laterally, we decided to go landscape.

It marked a turning point in the fortunes of the National Proposals team and of the firm in general. Clients noticed the change and commented, favourably. Partners also noticed and asked for their documents to be landscape, too. Of course, there’s nothing magic about the format, but it did enable us to handle things like graphics in a more visually interesting way. Because landscape allows you to divide the page into a two- or three-column grid, you can lay text out in columns, making it more readable. Most bid documents are text-heavy, so anything you can do to relieve this is a good thing. In MS Word, just insert a two-column table at the top of the page and drop your text into it, then adjust the column widths to create something like this…

FIGURE 4.1.Sample proposal page layout. Using a landscape format rather than portrait gives you more space for multiple graphics on the same page.

…or this:

FIGURE 4.2. Sample proposal page layout. A landscape format allows you to integrate graphics with introductory or explanatory text.

Dividing your page into a two- or three-column grid also shortens the average text width, enabling the eye to take in a line at a time – hence the narrow column width of most newspapers. Long lines of text are hard to read and tiring for the eyes: they trek along the line and then have to make the long journey back to the start of the next line.

The optimum width of text on printed matter is about 70 characters (i.e. about 12 words), and on a computer screen is about 50 characters.

Laying text out in columns makes it highly readable, with three advantages: it’s visually interesting for the reader; it complies with the optimum text width mentioned above; and it introduces white space down the middle of the page, which helps things stand out. Try it for key parts of your bid document.

PAGE LAYOUT: ENHANCING THE LOOK AND FEEL OF YOUR DOCUMENT

I’d like to talk about bullet points, but before I do, I must declare an interest. I’m taking my inspiration for this particular section from Jon Moon, whose terrific book How to make an impact (FT Prentice Hall) has changed how I look at document and information design. (You can download useful templates free of charge from Jon’s site, www.jmoon.co.uk/downloads_access.cfm; I recommend file 67, report templates you can pick ‘n’ mix from for your own free-form tender responses.)

Bullet points are over-used.

They were the shiny bright new thing when they were introduced in the mid-1980s, but now everyone uses them everywhere, whether to develop an argument, lay out an analysis, or list recommendations. And there’s a growing tendency to bullet whole paragraphs of text, which defeats their purpose.

Bullet points suffer from four shortcomings:

1. They’re so over-used they’ve lost any impact they ever had;

2. They tend to be a random list with no hierarchy or underlying structure, so they’re unmemorable;

3. They’re hard to refer back to: imagine trying to find a piece of information among a string of bulleted paragraphs;

4. They’re visually unappealing.

Jon is scathing about bullets: ‘Bullet points don’t break up dull text; they are dull text.’

(A quick solution is to turn your bulleted list into a numbered list. If you number the points, you’re more likely to think about their order, and it’s easier to refer to a particular point in a numbered list. The downside is that numbered lists imply a ranking of ideas, which you may not want.)

Figure 4.3 is an extract from a report showing the findings of a review of a retail store.

It’s dense and uninviting. The story isn’t clear. The conclusion comes right at the end, ignoring what we said earlier about inverting our (structural) pyramids. It defeats the purpose of bullet points by bulleting whole paragraphs, with little structure, navigation or clarity. You have to read the detail to get the main messages.

REVIEW OF OUR RETAIL STORE

The finding from a review of our retail store is as follows:

• We got a market research company to survey 100 people in the local area. Two-thirds of people said our products were ‘out-of-touch’ and ‘poor value for money’.

• As for the location, two years ago a large new retail centre opened nearby and is attracting many new shoppers to the town. Unfortunately our store doesn’t see them – the new centre is on the other side of the train and bus station from us. We’re now in a poor location - footfall through our side of town is down 35%.

• Also, the new retail centre provoked campaigns from local environmental activists. The local Council has bowed to this pressure and designated previously available sites as ‘green belt’. There is nowhere else now to develop which means we can’t relocate because of planning restrictions:

• Given all this, we recommend that we close our retail store.

FIGURE 4.3. Extract from a report, as bullets.

Jon has found a splendid alternative and he’s coined it ‘Words in Tables’ or WiT. Here’s the same text in WiT:

WHY WE SHOULD CLOSE OUR RETAIL STORE

Summary |

First, locals prefer other shops’ products. Even if they didn’t, we’re in a poor location. And because of planning restrictions, |

Locals prefer other shops’ products |

We got a market research company to survey 100 people in the local area. Two-thirds of people said our products were ‘out-of-touch’ and ‘poor value for money’. |

Even if they didn’t, we’re in a poor location |

Two years ago, a large new retail centre opened nearby and is attracting many new shoppers to the town. Unfortunately, our store doesn’t see them – the new centre is on the other side of the train and bus station from us. We’re now in a poor location. Footfall through our side of town is down 35%. we can’t relocate. Below are the details. |

We can’t relocate because of planning restrictions |

The new retail centre provoked campaigns from local environmental activists. The local Council has bowed to this pressure and designated previously available sites as ‘green belt’. There is nowhere else now to develop. |

FIGURE 4.4. Extract from a report, as a WiT.

Now, the main message (‘close the store’) comes first, followed by the evidence, rather than the bland title ‘Review of our retail store’.

The emboldened statements on the left summarize the key messages as a self-contained story, allowing superficial readers to scan them vertically and get the gist. The horizontal rules delineate each point and guide the eye of the reader along to the detail on the right, if that’s what they want. So the high-level stuff and the detail are separated, giving the reader a simple choice.

WiT helps the writer, too. Because the left-hand column ring-fences each point, it’s easy to see what belongs to each and what doesn’t. So it ensures that the author puts the right information in the right place, resulting in a clear, logical document.

The whole thing is visually more interesting and looks more professional.

Essentially, WiT is a table created in Word one row high by two columns wide. You can do it in seconds. In Word 2010, go to ‘Insert’, ‘Table’ (downward arrow), select two columns and the number of rows you want, change the column widths to ⅓ : ⅔, remove the side and internal borders, and Bob’s your uncle!

Even if you’re responding to a pro forma bid, with fields for your answer to each question, provided they are expandable and you don’t exceed the word limit, there’s nothing to stop you dropping a WiT into the relevant field.

TYPOGRAPHICAL DESIGN: USING FONTS AND TYPEFACES

TO MAKE YOUR POINT

Your choice of font and point size is important as it affects the overall readability of the bid document.

There are two categories of typeface: serif and sans serif. A serif is the tail, flare or dash at the end, top or bottom of a character; the best-known serif typeface is Times New Roman. ‘Sans’ is a French word meaning ‘without’, so Arial and Helvetica are sans serif typefaces as they lack the serif.

SERIF TYPEFACE e.g. Scott Keyser Proposals |

This typeface mimics traditional handwriting and inscriptional lettering, reminiscent of illuminated medieval manuscripts. In the name of my proposals business alongside, you can see the serifs at the top and bottom of the letters S, t, K, y, r, P, p, a and l. Accepted wisdom among typographers and graphic designers is that serif typefaces are best for narrative text and printed matter. The serifs act as a visual railway that guides the eye along the line, making the text more readable. On a screen, serifs are formed by single pixels, which can look like dust. That’s why serif typefaces tend not to be used for web or online copy. |

SANS SERIF TYPEFACE e.g. Scott Keyser Proposals |

Sans serif typefaces (e.g. Arial, Tahoma, Verdana) are best for text that will be scanned or glanced at, like headings and sub-headings, graph or chart labels, road signs, maps and text on a screen. These typefaces are ‘monoweight’, i.e. the ascenders and descenders of each character are the same size. There are no serifs or squiggly bits, so they are more legible. This is especially clear on a screen. Monoweight characters are formed by uniform numbers of pixels, so they look cleaner and sharper – which is why sans serif typefaces are preferred for web or online copy. |

Remember that Arial is a typeface or family of fonts, while ‘Arial Black 11 point’ is a font.

MIX AND MATCH TYPEFACE – BUT DON’T OVERDO IT

If your continuous text or prose is in Times New Roman, or Minion Pro (like this one), consider putting your headings and sub-headings in a sans serif typeface, such as Arial or Century Gothic (like the sub-heading above). This creates typographical variety in your document that will help keep your reader’s attention.

But don’t mix more than two typefaces on a page, unless you’ve studied design or typography. Too many typefaces can set up a conflict and look to the reader as if it’s happened by accident rather than by design.

CONTENTS AND PAGINATION

If your document is of a decent length and you want your client evaluator to be able to find what they need quickly and easily, you must have a list of contents at the front of the document.

Every version of Word allows you to insert a standard TOC (Table Of Contents), where you choose which level of heading to display. I usually go to two sub-levels, but it depends on how much detail you have in your document. As the document changes and grows, you can update the table by right-clicking on it and ticking ‘update entire table’. Just make sure that the first line of text beneath a section heading or sub-heading hasn’t taken on the style of that heading: if so, that line of text will also show up in the contents list.

Hand in glove with the contents list is the pagination. Make sure that the page numbers in the document footer are clear and not obscured by a copyright symbol or the name / reference no. of the bid. There’s nothing more annoying for an evaluator than page numbers and contents that don’t match up.

If your bid document is particularly long, with several sections, consider using tabbed dividers in a ring binder system. The advantage of a ring binder is that if different sections are marked by different people, they can be taken out and handled separately.

Use colour, too, but only as a navigational aid: colour-code different sections of the document for easy identification, but not the text. Keep the text the same colour: black. And don’t be tempted to play around with livid colour combinations to jazz up your document. They can make it look tacky and overworked.

HOW TO USE THE WRITTEN WORD TO WIN

Most of the hundreds of bid documents I’ve reviewed in my time suffer from five writing ailments:

1. Wordiness

2. Overly formal language

3. Long sentences

4. Jargon, management-speak and SOWs (Severely Over-used Words)

5. Dull language

In this particular section, I’m going to share six drafting techniques with you that, if you’re not already using them, will improve your bid documents (and most of your other sales communications) overnight.

I can make that bold claim because the techniques are so simple I’m amazed they’re not part of the British educational system’s National Curriculum. (I’ve actually identified 21 persuasive writing techniques, but sadly I don’t have enough space to go into them all here. I plan to write a book about them shortly, so keep your eyes on Amazon and the book-stands).

DRAFTING TECHNIQUE #1: OMIT NEEDLESS WORDS

Most bid writers want to write concisely – and most evaluators want to mark concise bid documents.

The single best way to write concisely is to omit redundant or needless words, i.e. words that don’t add any value, content, meaning or information. When we write concisely, we create text that’s like a piece of vacuum-sealed food: it’s tight, taut and fresh.

Here’s a list of 20 needlessly wordy phrases. Have a go at substituting them with one or at the most two words; you’ll find the answers at the end of this chapter.

1 for the purpose of

2 for the reason that

3 in order to

4 in the event that

5 on the grounds that

6 with reference to

7 face up to

8 assuming that

9 coming to an end

10 during the time that

11 due to the fact that

12 except in a very few instances

13 in close proximity to

14 it is often the case that

15 in short supply

16 involve the necessity of

17 make the acquaintance of

18 notwithstanding the fact that

19 on account of the fact that

20 subsequent to

At this point in my writing workshop, someone usually pipes up, “Yes, but if you want to impress the reader, surely it helps to use big words?”

I respond to this by asking a question back: “What’s the risk in using big words?” The obvious answer is that you might obscure your meaning and lose the reader. And that’s not going to impress them one bit.

What will most impress your reader?

Cracking content conveyed clearly and simply, such that they get it in one go. That will blow them away, partly because it’s rarer than hens’ teeth.

The belief that using fancy words will impress your reader and get them to do what you want is A BIG MYTH. Good ideas and great content stand on their own; they don’t need puffing up, tarting up or dressing up. And if you need to convey your ideas within a strict word limit where every character is at a premium, then you must write concisely.

I’d like to close Drafting Technique #1 by quoting from a gem of a book on writing, The Elements of Style, by William Strunk and EB White:

“Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts.”

It’s about economy of language.

DRAFTING TECHNIQUE #2: WRITE PLAIN ENGLISH

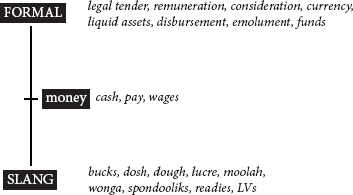

An important concept in English is register, a scale of the formality of writing. As you can see in the diagram below, the scale has ‘Formal’ at the top and ‘Slang’ at the bottom. Let’s use MONEY, a safe mid-register word, as an example and populate the register with synonyms for it (see figure 4.5).

In the upper reaches of the register we have words like remuneration, liquidity, finance, emolument, compensation and benefits; mid-register words like cash, pay and wages accompany money, while in the depths of the slang world we have words like bucks, dosh, dough, lucre, moolah, wonga, spondooliks, readies and LVs (Lager Vouchers), depending on which side of the pond you sit.

What do you notice about the upper-register words?

FIGURE 4.5. Register, a scale of the formality of writing. The best writers vary theirs.

They’re longer and harder to spell. They’re less well understood. They’re more elevated, formal, solemn, distant and aloof. They’re more exclusive, so they run the risk of alienating or distancing your reader. But if you’re trying to sell to me, you need to bring me in close and establish business intimacy with me. Using mid-register language will help me warm to you on a human level. If I feel distant from you, I’ll be less receptive to your message.

For instance, which of these two sentences makes you feel closer to me?

We will undertake collaborative in-depth ideas review and enhancement

or

We’ll look at the ideas with you and improve them together

I know which style I’d rather read.

Something else very important happens to language as we move up the register. I’ll give you a clue: take some money out of your wallet, purse or pocket and play around with it. Touch it, smell it, look at it. If it’s a coin, tap it on the table; if it’s a note, wave it in the air. Could you do that with any of the upper-register words?

No.

So as we move up the register, language not only becomes longer but also more abstract.

So what?

Abstract language is harder for the human brain to process. In the context of someone marking your bid, it’s in your interest to make their job as easy as possible. If you obscure your message with long, abstract words where they have to cudgel their brains to work out your meaning, there’s a risk they’ll give up and mark you down.

For clarity, directness and immediacy, the best place to be is in the middle of the register. While upper-register lingo tends to come from Latin and Greek, mid-register is the home of good old Anglo-Saxon. We call this plain English. So you understand exactly what I mean, here’s a short list of upper-register words and their plain English equivalent:

additional |

extra |

advise |

tell |

applicant |

you |

assist |

help, aid |

beverage |

drink |

commence |

start, begin, launch, kick off |

complete |

fill in |

comply with |

keep to |

consequently |

so |

construct |

build, make, create |

depart |

leave |

disseminate |

spread, share, scatter, give out, distribute |

forward |

send |

in excess of |

more than |

on receipt |

when we/you get |

particulars |

details |

per annum |

a year |

permit |

let, allow |

persons |

people |

personnel |

staff, people |

prior to |

before |

purchase |

buy |

should you wish |

if you wish |

subsequent to |

after, following |

terminate |

end, close, fire |

transmit |

send |

utilise |

use, apply |

As you can see, the plain English words on the right are shorter, pithier and universally understood. Everyone knows what cash is and what it does; not everyone knows what remuneration is or even how to spell it – and why should they?

Now, this comes with a caveat: if remuneration is precisely the right term for your technical context – for instance, if you’re addressing a company’s Remuneration Committee – then that’s the word you must use. But if all you mean is, ‘You’ll get more cash in your pocket at the end of the month’, then use the everyday English equivalent.

My message here is that you have a choice: you don’t have to use upperregister language all the time for serious documents like bids or tenders. Vary your register. Great writers like the journalists who write for The Economist bounce up and down the register all the time. They have the intellectual confidence to refer to the UK’s immigration policy as barmy, Thabo Mbeki as prickly or the future as dicey.

Sometimes they vary the register within a phrase, let alone a sentence or a paragraph. When John McCain ran against Barack Obama in the 2008 US presidential election, The Economist published an in-depth profile of McCain where they described him as having ‘a blokeish persona’. Blokeish is an Anglicism from the slang word ‘bloke’, meaning laddish or ‘one of the boys’, while persona is an upper-register Latin word meaning ‘public face’ or ‘mask’.

The point about mixing up the register is that it makes your writing more interesting; you can achieve more varied effects than if you stay rooted in one level of formality. It also allows the writer’s personality and voice to come through, another property of good writing.

Convinced about the merits of plain English? If not, consider yet another benefit, this time for you as the writer. Not only is plain English clearer for your reader, it’s also quicker and easier to draft than higher-register language because that’s how most people speak.

It’s ironic that some writers reach for Roget’s Thesaurus every five minutes to move their writing up the register, while their reader will reach for the Oxford English Dictionary to bring it back down so they can understand it! Talk about not connecting with your reader.

Here’s a final example of plain English, again from The Economist. It’s the concluding paragraph of an article about Kweku Adoboli, the UBS rogue trader who was jailed in November 2012 for losing the Swiss bank $2.3 billion:

Take a smart and ambitious person, give him billions to play with, push him to make as much money as he can and do away with adult supervision. The lesson is that this is a recipe for financial disaster.![]()

DRAFTING TECHNIQUE #3: USE POWER WORDS

A ‘power word’ is a word with emotional kick. Its impact comes from where it lives on the register: the middle.

Because plain English is concrete, everyday language, it’s more visual and has more resonance than higher-register lingo.

So you could say

The Civil Engineering division has reduced its budget for next year.

But if you wanted more impact you could say

The Civil Engineering division has slashed its budget for next year.

You can’t picture a ‘reduction’ because it’s an abstract concept, but you can picture a sword slashing something (or someone) in half.

Take the sentence:

This law will negatively impact on our profits.

Does that have emotional kick? Not really. The phrase ‘negatively impact’ is ambiguous: it could be a huge impact or a tiny one. It’s weasel-wording, hedging-your-bets, sit-on-the-fence, non-committal language (and, by the way, one of a slew of phrases that the British Foreign Office is trying to banish from its communications).

If you wanted to be more measured, you might say

This law will hurt / damage / harm our profits.

But if you wanted a greater emotional reaction from your reader, you could say

This law will cripple / crucify / wreck / ruin / maim / destroy our profits.

Can you hear and feel the difference? We call these ‘power words’. Of course, it’s up to you to choose the word that is appropriate, accurate and effective.

DRAFTING TECHNIQUE #4: USE MORE VERBS THAN NOUNS

A serious disease afflicting bids and tenders is nounitis, the excessive use of nouns.

First diagnosed by Rupert Morris, a writing doctor, it’s infectious and widespread. But it’s also curable. The cure? Use more verbs. Here’s an example:

Our specialism is the provision of taxation solutions.

Sounds OK at first blush, but if you identify all the nouns, you’ll quickly see it’s suffering from acute nounitis. I’ve underlined the nouns:

Our specialism is the provision of taxation solutions.

It’s bogged down by four abstract nouns, three of which end in -ion, so it sounds repetitive and samey (plus the only verb is ‘is’). Remind me, what’s a noun? It’s a naming word (I often hear ‘It’s a person, place or thing’, which is fine too). The problem with nouns is they just sit there naming stuff, but don’t do anything. If the universal cure for nounitis is to use more verbs, what’s a verb? It’s an action or doing word. So apply the cure to Version 1 and you get:

We specialize in providing taxation solutions.

That’s better, because at least we’ve got one strong verb in specialize and we’ve turned provision into a gerund (a verbal noun ending in -ing).

But there’s a problem with this version: a big fat S.O.W. (Severely Overused Word) is running around. Provide. I’d put good money on the fact that provide (and all its horrible relations) is the single most over-used word in bids and tenders, bar none. Not only that, but it’s a major carrier for the nounitis virus. Whenever you use the word, you have to follow it with a noun, e.g. we provide advice, we provide support, we provide briefings, we provide guidance. Just use the verb, e.g. we advise, we support, we brief, we guide. It will work in most contexts.

So you’re banned from using provide in the next and final version. What does that force you to do?

We specialize in solving your taxation problems.

I’ve underlined the verbs and personalized the sentence by adding your. If you object to the word problems in a sales document, you could use alternatives like issues, needs or challenges.

So how do you self-diagnose? How do you know if you’ve got nounitis?

Go through your text and note all the words ending in:

• tion (e.g. facilitation, implementation, collaboration, delegation)

• sion (e.g. conversion, provision, decision)

• ism (e.g. specialism, magnetism)

• ity (e.g. capability, adversity, speciality)

• ment (e.g. management, judgement, assessment)

• ance (e.g. performance, maintenance)

Take your writer’s scalpel and lop off those endings to revert to the root verb. You win in two ways: you invigorate your writing by using more words of action/doing, and you make it briefer, as the verb is always shorter than its noun equivalent.

What’s not to like?

DRAFTING TECHNIQUE #5: TURN YOUR PASSIVES INTO ACTIVES

As insidious as nounitis is the passive voice. It’s crept into most business writing like a thief in the night. I call it the carbon monoxide of your writing, the silent killer. Most business writers write in the passive voice and they don’t even know they’re doing it.

To cure your passivitis, you first need to understand its inner workings. I often use this example because it’s so simple:

The cat sat on the mat.

The cat is obviously the subject or agent of action, sat is the past tense of the verb to sit, and the mat is the object (it’s what the sitting is being done to).

This gives us a declarative sentence: Subject – Verb – Object, meaning that that sentence is in the active voice (AV).

The passive version of the same sentence is

The mat was sat on by the cat.

Now what’s the subject? No, not the mat! The mat’s still the object, it’s what’s being sat on, isn’t it? So the passive version goes Object – Verb – Subject, i.e. the subject and the object have switched places. The sentence has also acquired additional words, like was and by, which you need to form the passive. We describe this sentence as being in the passive voice (PV).

What obvious difference between the two versions do you notice?

Yup, the passive version is longer, 33% longer in fact (eight words vs. six is an increase of 33%). And is there any difference in meaning? None. So if you’re a fan of the passive voice, your writing will be a third longer than it needs to be with no added value, content, meaning or information. And that’s a big deal if you’re working within a strict word or character limit when responding to an ITT or RFP.

How else do the two versions differ?

Well, the passive one is less direct, more complicated and makes your reader’s brain work harder to decode its meaning. In the context of one simple sentence like this one, you may think this is all a storm in a teacup, but over a 30- or 40-page document cumulatively it will make a big difference.

I’m advocating that you use the active voice much more than the passive. The active voice is briefer and forces you to state who is doing what to whom. Simple, clear, direct.

However, there are four occasions when it’s OK to use the passive:

1. To cover your backside.

The passive voice lets you drop the subject, e.g. ‘The mat was sat on’ is grammatically correct, but we no longer know who did the sitting. So use the passive if you want to hide responsibility for something, or be less confrontational. For instance, you often hear government representatives after a disaster or scandal using language like ‘Mistakes were made, targets were missed but lessons will be learnt’. Classic butt-covering language courtesy of the passive voice.

2. To emphasize the object.

As the passive forces you to put the object at the front of the sentence, this automatically emphasizes it. Based on the theory of primacy, the first word or idea in a sentence gets the reader’s attention. So we might say The handcrafted, velvet-tufted 13th-century Baluchistan rug was sat on by the cat.

3. When the subject is unknown.

Use the passive if you don’t know who or what the subject is, e.g.:

It is alleged that a murder took place (you don’t know who made the allegation)

A shot was fired (don’t know who the shooter was)

Our friends were burgled last night (they don’t know who burgled them).

4. When the subject is unimportant.

The file was uploaded to the server and The meeting was convened for Tuesday are classic examples of the subject not mattering. It’s immaterial who or what uploaded the file; it was probably an automatic process anyway. And does it matter who convened the meeting? These are two examples where the action is more important than the actor.

A word of warning on the passive voice: people sometimes confuse voice with tense, but they’re two different things. The voice of a sentence is binary: it’s either active or passive. A tense, however, locates an action in time, e.g. ‘We are being offered a discount’ is in both the present tense and the passive voice; ‘we were offered a discount’ is in the past tense and the passive; ‘we will be offered a discount’ is in the future tense and the passive.

Sorry if you already know this, but some people think you can’t change tenses in the passive; you can. So, to revert to our original example, you can just as easily say

The mat is being sat on by the cat (present tense + PV)

as

The mat will be sat on by the cat (future tense + PV)

as

The mat would be sat on by the cat, if the cat was in the room

(conditional tense + PV).

My take-away message, though, is this: if you want your writing to be briefer, more direct and more dynamic, make the active voice your voice of choice.

DRAFTING TECHNIQUE #6: SHOW, DON’T TELL

There’s a widespread tendency in sales documents to tell the client what you’re good at, but not demonstrate it. This generates what I call the Super-Smashing-Great school of writing:

We are committed to providing you with unique, exciting, best-of-breed, state-of-the-art, cutting-edge, market-leading IT solutions that will transform the productivity of your sales force and streamline your sales process.

This horrible sentence is awash with generic, boastful, cliché-ridden but unsubstantiated claims with a high BS-quotient that will send the evaluator running for the hills.

Anybody can make claims like this, but as Rod Tidwell (played by Cuba Gooding, Jr.) says in the Tom Cruise movie Jerry Maguire, ‘Show me the money!’ To be credible and get a good client score, you must do more showing than telling. This is what I mean:

If you appoint us, you will get access to generation 4.5 of our ‘Window to Win’ proprietary consultative selling CRM (Customer Relationship Management) system.

Developed in partnership with NASA specifically for the management consulting industry, ‘Window to Win’ allows you to track every single contact with every sales lead, prospect or customer on any device you want, whether laptop, PC, mobile phone or even your television.

The system guides you and your sales people step-by-step through the sales process to:

![]() target an industry sector or niche

target an industry sector or niche

![]() pre-qualify ‘suspects’ into prospects

pre-qualify ‘suspects’ into prospects

![]() get their attention in innovative ways

get their attention in innovative ways

![]() build rapport with them quickly

build rapport with them quickly

![]() prove to them the value of doing business with you

prove to them the value of doing business with you

![]() convert them into customers

convert them into customers

![]() increase the number of times they buy from you

increase the number of times they buy from you

![]() boost the average value of each sale

boost the average value of each sale

![]() bill them

bill them

![]() track their contribution to your sales targets and your sales team’s ROI

track their contribution to your sales targets and your sales team’s ROI

![]() keep in touch with them throughout the life of your relationship

keep in touch with them throughout the life of your relationship

What’s different about ‘Window to Win’ is that wherever you are in the sales process, the system prompts you with suggestions for how to move the lead on to the next stage. Based on proven consultative selling techniques, these suggestions mean that you are never at a loss for how to progress a prospect. The system also reminds you when you’ve let a lead lapse or haven’t been in touch with a customer for a certain period of time. It also contains a matrix for tracking the quality of your relationship with the lead and other relevant stakeholders.

The results speak for themselves. 98%* of management consultancies who have licensed ‘Window to Win’ have seen their sales grow by at least 45% in 18 months, while 97%** say they would strongly recommend it (but not to their competitors!)

* Independent research conducted with a sample of 56 clients in June 2012

** Focus groups held among 38 clients in November 2012

“Despite the fact that ‘Window to Win’ is the most expensive CRM on the market, it’s already paid for itself three times over. We are winning work that before we wouldn’t even have looked at. It’s put rocket fuel in our sales – and our sales people!”

Joe Bloggs, Sales & Marketing Director, Widgets Inc.

OK, I know I went a bit over the top there, but you get the idea.

Though my version is fanciful, it’s crammed full of specific, concrete and definite features and benefits, with compelling third-party evidence in the form of market stats and a client testimonial.

Of course, it’s much longer than the original sentence, but that’s because I’ve drilled down through several layers from the surface. Now it gives the reader much more information to base their decision on. You’ll find that when you start showing not telling and going to town on the benefits, you’ll use more words. And you’ll avoid the management-speak, buzz-words and MBA-itis that puts most clients off.

HOW TO EDIT AND CHECK YOUR BID DOCUMENT

You’ve produced your first draft, but you’re not going to send it, are you?

Professional writers never send their first draft, because it’s usually half-baked and hasn’t enjoyed the sculpting, re-drafting and polishing it needs. If you have to send your first draft because you’ve run out of time and the tender deadline approaches, something’s gone seriously wrong with your process.

So pull on your editor’s green eyeshade and let’s go.

Whether you’re editing an entire bid document or a single answer, you’d be well advised to ask (and answer) the following questions, in this order:

1. Is it fit for purpose?

Is your text broadly doing the job you need it to do? Will it make the reader do what you want them to do? Does it answer the question?

2. Does it tackle the right issues in the right order?

If you’re answering a specific question in a pro forma bid, your text must answer the question as directly and immediately as possible. If the question asks for several things in a certain order, it’s usually a good idea to reflect that in your answer, provided the order is logical.

If you do decide to deviate from the order in which the client posed the question(s), explain why.

3. Is it clear and concise?

Your reader/evaluator must ‘get it’ in one go and not have to re-read it to understand what you mean. So use simple but not simplistic language; make it easy for them. Would someone not involved in the bid be able to understand it? Clarity is vital, so plain English is usually the way to go.

4. Does it speak to the reader in language they will understand and respond to?

Plain English and appropriate technical jargon can co-exist in a bid. If your reader is highly technical, then liberally use the jargon they will understand (and may expect). If your content is highly technical, then offset it with simpler supporting language.

If there is a chance, however, that other readers may be non-technical, then go easy on the jargon. If you must use it, perhaps clarify it or spell it out. You might consider including a glossary of terms in your document. This makes clarification available to readers who need it, while avoiding the risk of patronizing them by explaining too much in the text.

5. Is it attractively laid out?

As you cast your eye over the document, is every page easy on the eye? Is it breathable, with lots of white space? Is it visually interesting, using graphics like charts, tables, photos, diagrams and flashes well? Or are all the pages so similar that they merge into one, with little contrast or differentiation?

The section on document and information design earlier in this chapter has plenty of ideas for improving the ‘look and feel’ of your document. I’m a great believer in making any communication an enjoyable experience for the reader, so also consider elements of your document like paper stock (i.e. quality and weight of paper), a properly designed cover, and clear headers and footers.

HOW MANY DRAFTS SHOULD YOU DO?

There’s no magic rule, but the bare minimum is three:

Draft 1: likely to be half-baked, with typos.

Draft 2: spell-checked.

Draft 3: printed out and proofread.

As you can see, that’s pretty sparse. No omission of needless words, no pruning of structure or style, no attempt to modulate tone of voice. So if you can, go to five drafts:

Draft 1: half-baked initial attempt.

Draft 2: broad assessment against your objective.

Draft 3: check structure, flow, big picture stuff. Does it hang together, does its architecture make sense and/or reflect what the ITT or RFP asked for? Survey the list of contents for a quick and easy way of checking this.

Draft 4: review for style, word choice, tone of voice, punctuation.

Draft 5: spell-check it, print it out and proofread for typos.

Here are the tools you should use on your drafts, in this order:

Deforest your text with a hefty chainsaw, taking out whole sections and pages. Then use the garden secateurs to trim paragraphs and sentences. Finally, excise individual words and phrases with a surgeon’s scalpel. Too often I see writers pruning the leafy treetops when they should be attacking the trunk, and vice versa.

I’d like to spend a few more lines on drafts 4 and 5.

ROL AND THE READABILITY STATS

At draft 4, there are two useful ways of checking the style and language of your text. The first is a highly technical device, derived originally from subatomic physics and quantum mechanics (only joking). It’s called READ IT OUT LOUD, or ROL, and every professional writer does it.

I mentioned this earlier in the chapter, but it bears repetition.

ROL slows you down and allows you to hear how your text will sound to the reader. After all, we don’t read tone of voice, we hear it. But ROL also catches the clumsy phrase and the sentence that runs on and on (when you start to get breathless). When we read our own text to ourselves or scan it, our brains tend to go on auto-pilot and insert what we want to be there or think is there, but which actually isn’t. ROL stops that in its tracks. It’s such a simple technique, there’s no excuse for not doing it. (If you work in an open-plan office and worry about disturbing your colleagues – or making them worry about your sanity – find an empty meeting room or go for a walk in the park.)

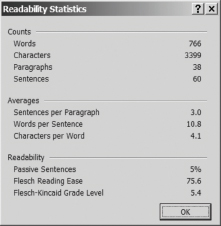

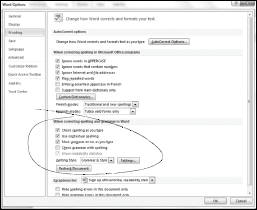

The second technique, coming to a screen near you, is more technical than ROL, but even easier. It entails running the readability statistics available in every version of Word. This is what they look like:

FIGURE 4.6. The Readability Statistics, available in all word processing applications. The stats give you feedback on key ratios in your text.

Based on the work of Dr Rudolf Flesch, a Viennese psychologist who fled Nazism in the 1930s and settled in New York, the stats allow you to score the readability of your own writing – and other people’s, provided you have an electronic copy (I’ve seen this spawn some healthy interdepartmental competition).