![]()

Home Experiences Related to the Development of Word Recognition

Linda Baker

Sylvia Fernandez-Fein

Deborah Scher

Helen Williams

National Reading Research Center

and

University of Maryland Baltimore County

Researchers have documented many aspects of the home environment that seem to be important for optimal literacy development (for reviews, see Guthrie & Greaney, 1991; Morrow, 1989; Snow, Barnes, Chandler, Goodman, & Hemphill, 1991; Sonnenschein, Brody, & Munsterman, 1996; Sulzby & Teale, 1991). In this chapter we focus specifically on the role of home experiences in promoting the development of word recognition skills, a topic that has not been systematically explored either empirically or theoretically.

Other chapters in this volume have made it clear that phonological processing and grapheme-phoneme knowledge play critical roles in the development of word recognition (e.g., Ehri, chap. 1; Metsala & Walley, chap. 4). What role does the family play in the development of such skills? In the first section, we present descriptive evidence about children’s home experiences that might be relevant to the development of word recognition. We consider home experiences relevant to the development of print knowledge and phonological awareness, based on information from parental reports, home observations, and analyses of parent-child interactions during book reading. Given the well-documented evidence of differences in the reading attainment of low-income and minority children, many researchers have looked to differential home experiences as contributing factors. Accordingly, we discuss available evidence of sociocultural differences in experiences related to word recognition to shed light on this issue. In the second section, we examine relations between children’s home experiences and their emergent competencies in areas relevant to beginning reading. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the implications of the research for providing sound guidance to parents.

WHAT KINDS OF EXPERIENCES DO CHILDREN HAVE AT HOME THAT MIGHT FACILITATE THE DEVELOPMENT OF WORD RECOGNITION?

Children’s Everyday Home Experiences Involving Print

Virtually every study of home influences on children’s literacy development includes surveys, questionnaires, or interviews designed to acquire information about children’s home experiences with print. Some studies also include qualitative examinations of children’s experiences involving print, relying on direct observations of home literacy activities or parental diaries. One home literacy activity—shared storybook reading—has garnered particular attention. We discuss relevant data in the sections that follow.

Parents’ Responses to Questionnaires and Rating Scales. A major source of information about children’s home experiences is an ongoing longitudinal study directed by Linda Baker, Susan Sonnenschein, and Robert Serpell. It focuses on the development of literacy in urban children, both African American and European American, low income and middle income, and it includes a broad array of measures of home experiences, parental beliefs, and children’s competencies (see Baker, Sonnenschein, et al., 1996; Baker, Serpell, & Sonnenschein, 1995; Baker, Sonnenschein, Serpell, Fernandez-Fein, & Scher, 1994; Serpell et al., 1997; Sonnenschein, Baker, Serpell, Scher, Fernandez-Fein, & Munsterman, 1996; Sonnenschein et al., 1997). Throughout this chapter we refer to the study as the Early Childhood Project. When children participating in the project were in prekindergarten, their mothers were questioned about children’s participation in specific activities with the potential to foster the development of knowledge and competencies associated with early reading (see Baker et al., 1994, for details). The parent indicated the frequency of the child’s participation in each activity using a four-point scale: 0—never; 1—rarely, less than once a week; 2—occasionally, at least once a week; and 3—often, almost every day. Within the area of reading, writing, or drawing activities, the parent rated engagement with the following specific types of books: educational (e.g., ABC books), picture books (i.e., books without a printed story), storybooks, and nonfiction books, as well as other printed material (e.g., magazines, comics); drawing; writing; and looking at books on his or her own.

All children participated regularly in experiences relevant to the development of knowledge about print. They had frequent experiences with storybooks; the overall mean rating was 2.39. No other types of books had mean frequency ratings above 2.0. The mean frequency rating for the child looking at books independently was 1.75, and the mean rating for writing was 2.39. The percentages of parents who reported that their child interacted with at least one type of book every day or almost every day differed as a function of income level; 90% of the middle-income parents reported daily book reading activity, whereas 52% of the lower-income parents did so. Income-related differences were also evident in reported frequency of visits to the library, favoring middle-income families.

Additional information about home literacy experiences relevant to the development of print knowledge comes from studies by Raz and Bryant (1990), Chaney (1994), Marvin and Mirenda (1993), and Elliott and Hewison (1994). Of particular interest in these studies, as in the Early Childhood Project, was whether there were sociocultural differences in the nature of children’s experiences. In the Raz and Bryant study, low-income and middle-income parents of British preschoolers reported that their children looked at books on their own with comparable frequencies, but middle-income parents reported more frequent reading to their child, more books owned by the child, and more visits to the library. In Chaney’s study, parents of 3-year-olds from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds reported that their children received some exposure to print. However, middle-class families routinely provided abundant exposure to a wide variety of literacy experiences, whereas the quantity of literacy experiences varied more among poorer and less well-educated families.

Marvin and Mirenda (1993) compared the home literacy experiences of low- and middle-income children using a mailed parent survey. Over 80% of all parents reported their children had access to picture or storybooks at home, 63% said the child used some type of reading material at home at least once a day, and 60% said their child practiced writing letters. Children also did not differ in their independent experiences with print. However, middle-income children reportedly went to the library more frequently and had more adult literacy materials in their homes.

Elliott and Hewison (1994) examined the home literacy activities of a somewhat older sample, 7-year-old British children from middle- and low-income families. Middle-income parents reported more frequent reading stories to their children, using flashcards to help children learn words, hearing children read, having books and magazines in the home, and having children experiment with the creation of words and sentences using flashcards.

We cannot compare the findings from these studies directly because of differences in the instruments and differences in the participant samples. Nevertheless, the general consensus is that children from various sociocultural groups have many relevant home literacy experiences, but middle-income children tend to have more frequent and/or more varied experiences of one sort or another.

It is often difficult to draw conclusions from the broader literature about the opportunities children have for learning skills related to word recognition in particular, because data are often aggregated across questions. Thus, researchers might ask parents whether they teach children letters of the alphabet and whether they play games with rhymes, but then the researchers create a composite measure of home literacy experience that incorporates responses to these questions along with questions about storybook reading and environmental print.

Interpretation of parental reports must always be made cautiously, especially when sociocultural differences are indicated. It may be that middle-income parents are more sensitive to societal expectations and thus more likely to respond based on social desirability. Senechal, LeFevre, Hudson, and Lawson (1996) recently argued that frequency ratings are subject not only to social desirability bias but also to variations in parents’ interpretations of the questions and their difficulties in determining frequency reliably.

Observations and Parent Diaries. Reliance on ratings scales provides a limited picture of what is really going on in children’s everyday lives. Observational and ethnographic studies have demonstrated that children in low-income and minority families do indeed have many experiences with print in their everyday lives, albeit not necessarily the conventional middle-class storybook reading (Anderson & Stokes, 1984; Goldenberg, Reese, & Gallimore, 1992; Heath, 1983; Taylor & Dorsey-Gaines, 1988; Teale, 1986). For example, Teale (1986) observed everyday home literacy experiences of low-income children of various ethnicities. He categorized the experiences into the following domains: daily living, entertainment, school or work related, religion, interpersonal communication, getting information, and literacy for the purpose of teaching the child. Few of the families engaged in frequent literacy activities for this latter purpose, nor did they read for pleasure; most reading was done for functional purposes.

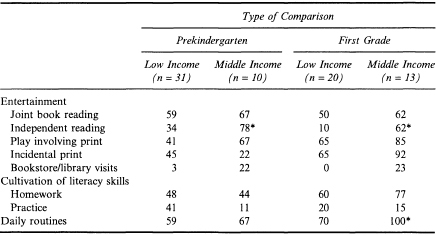

Parents of children in the Early Childhood Project kept a diary documenting all of the activities that the child engaged in during the course of 1 week. The parents were not informed that our primary interest was in literacy, so their records were unlikely to be biased in this direction. A coding scheme for characterizing the reported experiences with print was devised, influenced in part by Teale (1986) and Goldenberg et al. (1992). We identified three main uses of literacy in the activities involving print, corresponding to three broad cultural themes: literacy is a source of entertainment; literacy consists of a set of skills that should be deliberately cultivated; and literacy is an intrinsic ingredient of everyday life, figuring prominently in daily living routines. Within the entertainment category were the following activities: joint book reading; independent reading; play involving print; incidental exposure to print; and visits to libraries. Within the skills category were homework and practice (Baker et al., 1994).

Table 11.1 shows the percentages of parents of prekindergarteners and first graders spontaneously reporting activities in each category as a function of income level. Consider first the prekindergarten data. The only significant income difference was in the entertainment domain; more middle-income parents than low-income parents reported that children interacted with books independently or of their own initiative (78% vs. 34%). Income differences were also evident in the proportion of print-related activities reported in the diaries that fell into each of the three broad domains. For the middle-income parents, the categorical distribution was 70% entertainment, 11% skills, and 20% daily living; whereas the distribution for the lower-income parents was 47% entertainment, 36% skills, and 17% daily living. These data suggest that middle-income families tend to show greater endorsement of the cultural theme of literacy as a source of entertainment than do low-income families, whereas low-income families tend to give more attention to the theme of literacy as a skill to be deliberately cultivated.

Consider now the diaries of the parents of first graders. Middle-income parents again reported that their children interacted with books independently or on their own initiative more frequently than the low-income parents reported concerning their own children (62% vs. 10%). Middle-income parents reported at least one instance of a daily routine involving literacy, whereas only 70% of the lower-income parents did. With respect to the proportion of print-related activities reported in the diaries that fell into each of the three broad domains, more than half of the references to literate activity reflected entertainment uses, whereas almost one third dealt with the cultivation of literacy skills. There were no significant income differences with respect to the skill theme as there were for children who were 2 years younger, perhaps because first graders were receiving explicit instruction in learning how to read in school.

Percentages of Parents Spontaneously Reporting Children’s Print Related Experiences in Various Domains at Least Once in Diaries

*Comparisons of the two means immediately to left of asterisk were significant at p < .05.

The value of the diaries as a source of information about experiences relevant to the development of word recognition can best be revealed through the parents’ own words. A mother of a prekindergartner illustrated the child’s attention to words during storybook reading: “Him and daddy will read a book. He likes to listen to you when you read to him and then he likes to tell you the words you told him, so that makes it likes he’s reading the book to you, but he’s just memorizing the words.”

Another mother described her prekindergarten child’s independent interactions with a book (he read three “Spot” books): “He likes to lift the flags. Also, they are short and words are big, so he memorizes them very easily and pretends—or actually thinks—he’s reading.”

In one family, the prekindergarten child was so interested in print that she asked about letters on piano music books: “She was asking what letters on music were—she would point to a letter and I would tell her what it was; she would point to another letter, trace it with her finger … and when she finished with saying the words, she went back over it and say it.… She seemed to remember the letters as we came along them when we go to one she remembered, she would say it before I would say it.”

Diaries of parents of the first graders included somewhat different experiences than did those of the prekindergarteners, although joint book reading was still a popular event. However, the interactions surrounding the book readings seem to have changed: “After reading her the story we discussed it to try to identify the characters and see if she understood what was read.” The first-grade children appeared to be fascinated by the mechanics of reading and writing: “He sat next to me on the couch, asking, of course, many questions and he’s intrigued by spelling words, so he’ll spell them and I have to tell him what they are.” The children also spent a lot of time playing school: “[Child], [brother], and [friend] went up to her room to play school. She was the teacher and she had a blackboard and chalk and was giving [brother] and [friend] homework.” There was evidence that children were trying to read on their own and they were getting help from parents and siblings: “He is really starting to get in to reading alot. We all take turns helping but [older sister] must get alot [sic] of created [credit]. He likes to read to her more cause she makes a game out of it by playing school with him.”

Parents of both prekindergarteners and first graders made many references to encouraging writing and reading through homework or practice of skills. Among the prekindergarten parents, one mentioned making her child “some dots of his name, address, and phone number to trace.” Another parent mentioned she was “teaching her [child] how to spell and to identify the letters in her name using paper and pencils and flashcards.” Many parents mentioned that their children were learning their ABCs through various means. One child was “playing with ABC magnets on refrigerator and singing ABCs.” Another child was “learning how to write her ABCs and numbers.” One mother observed that her child “traces ABCs from plastic to paper.” Homework also facilitated learning the alphabet: “homework was the letter R, tracing the letter r, cutting out pictures that begin with the letter r.” A parent of a first grader noted that her child “comes home from school and shows me her list of words for the upcoming week. We take 10 minutes to have her point and say different words.”

References to attention to print in daily experiences most frequently focused on the child picking out items in grocery stores. A parent of a prekindergartener wrote, “unloaded groceries. He has a good time spelling every cereal box … draws on chalkboard with cereal box to copy letters.”

As with rating scales, there are limitations to the diary approach in acquiring information about children’s home experiences with print. Parents varied greatly in the amount of information they provided us, and failure to mention particular activities does not necessarily mean that they did not occur. However, the diaries are important because they show what parents choose to reveal about their children’s everyday lives. The parents’ values, as well as their perceptions of what the researchers really wanted to know, undoubtedly influence the content that gets recorded. The fact that middle-income parents wrote more about reading for entertainment than did low-income parents provides an indication that the middle-income parents view literacy as a source of pleasure, even if we must be cautious in inferring true differences in children’s experiences. Another facet of the Early Childhood Project that assessed parents’ beliefs about reading provided converging evidence that this sociocultural difference is real (Sonnenschein et al., 1997).

Shared Storybook Reading. As Snow (1994) argued, storybook reading may be construed less as an event in itself but rather as a microenvironment in which relevant experiences occur. Thus, it is not only the act of reading that is important, but also the kinds of conversations that reader and child have with one another during the reading session, the affective quality of those interactions, the print-related discussions that might ensue, and so on. This suggests that frequency measures alone are not very informative; qualitative analyses of what goes on during book reading interactions are also needed. This is especially true when the goal is to identify aspects of story-book reading that may be conducive to the development of word recognition. Even qualitative analyses have not proved very informative to date, because few researchers have examined the nature and degree of print-related talk during the book readings; the focus is typically on content-related questions and commentary, and talk about nonimmediate events (e.g., Bus & van IJzendoorn, 1995; Dickinson, DeTemple, Hirschler, & Smith, 1992; Pellegrini, Perlmutter, Galda, & Brody, 1990). On the other hand, as we see later in our discussion, the few studies addressing this issue have reported minimal attention to print during storybook reading (Bus & van IJzendoorn, 1988; Munsterman & Sonnenschein, 1997; Phillips & McNaughton, 1990; Yaden, Smolkin, & Conlon, 1989).

Phillips and McNaughton (1990) asked 10 middle-income New Zealand parents to read researcher-supplied narrative storybooks with their 3- and 4-year-old children over a period of 4 or 6 weeks. They coded the types of “insertions” (comments and questions) made by the reader or the child as to whether they were print related (references to letters, words, pages, and book handling), narrative related, or other. Only 3.3% of the total insertions were print related, whereas 85% were narrative related. Despite this lack of attention to print during storybook reading, the children knew an average of 13 letters, 2 words, and 5 concepts about print.

Similar lack of speech about print was evident in analysis of dyadic storybook reading within the Early Childhood Project (Munsterman & Sonnenschein, 1997). Kindergarten children were observed during shared book reading with the person they were most likely to read with at home, usually either the mother or an older sibling. There were 30 dyads, 25 of whom were low-income. All parents reported at least occasional shared storybook reading; only 3 said this occurred less than once a week. Each dyad read one unfamiliar storybook supplied by the researcher and, if available, one familiar book from the child’s home library. Munsterman and Sonnenschein coded the utterances into the categories of content-related immediate speech, content-related nonimmediate speech, story structure/organizational speech, and print/skills related speech. Examples in this latter category are: “N is also in your name” and “What’s that word? Spell it.” Print/skills-related and nonimmediate content-related utterances occurred least frequently and did not differ from one another; content related-immediate talk was most frequent. Only 6.3% of total speech was skills/print related, and the mean frequency of such speech was .82 utterances per book. However, print-related talk was more common with certain types of books, such as rhyming, alphabet books or predictable language books. Fifteen percent of the familiar books read were of this type. The percentage of skills comments during readings of these types of books was 64%, with a frequency of 5.75 per book, in contrast to the percentage of skills comments for all familiar books of 11%, with an average of only 1.48 utterances per book. Parent and sibling readers did not differ significantly in the extent of print-related speech.

Bus and van IJzendoorn (1988) systematically compared interactions across the two genres of books: storybooks and ABC books. They found that mothers of 3- and 5-year-old children engaged in more talk about the print in the ABC book than that in the storybook. Moreover, the children engaged in more “protoreading” behaviors with the ABC book; for example, they tried to spell words and identify letters.

The child’s own contribution to the book reading interaction is perhaps more important than the parent’s. Information that the child solicits may be processed more deeply because it is of greater interest to the child than is unsolicited information provided by the parent or questions asked by the parent that disrupt the child’s own engagement in the story. As Yaden et al. (1989) noted, there has been much anecdotal evidence that children ask questions about the print they encounter, but not much systematic investigation. Durkin (1966) asked parents whether early readers asked about letters, words, sounds, and other aspects of books. Durkin found that they did, but most research suggests that the majority of questions asked by preschoolers focus on illustrations rather than print.

Yaden et al. (1989) explored the kinds of questions preschool children spontaneously asked during storybook reading at home with parents over the course of 1 or 2 years. Questions included those about (a) graphic form (letter configuration, letter name, letter sound, punctuation, written word form, written word name, spelling, form of multiple word arrays, name of multiple word arrays); (b) word meanings; (c) oral (story) text; (d) illustrations; and (e) book conventions. Children asked the most questions about illustrations, followed by questions about story text; there were far fewer questions about graphic form, although all children did ask such questions. The percentages of total questions about graphic form ranged from 3% to 24% (mean = 8.4). The child who addressed 24% of his questions to print was reported by his mother to be asking about other print in his environment and seemed to be trying to decode on his own. Consistent with findings discussed previously, questions about print were more likely with certain types of books, such as alphabet books and a book with big speech balloons. Perhaps when print is more salient in a book, children’s attention is more likely to be directed toward it.

The familiarity that occurs with repeated readings of a book also leads children to focus more attention on print, as shown in a school-based study by Morrow (1988). Morrow suggested there may be a developmental transition in the kinds of things children talk about during storybook reading; the earliest appearing focus is on illustrations, then story meaning, and only later on print. Bus and van IJzendoorn (1995) proposed a similar developmental model.

Information relevant to learning about print through shared storybook reading comes not only from analyses of interactions when parents read to children, but also when children read to parents. Elliott and Hewison (1994) observed 7-year-old children in Britain from various sociocultural groups read aloud to their parents, and analyzed the kinds of corrections that parents provided. Working-class families put a strong emphasis on phonics when correcting (e.g., sound it out), whereas the middle-class mothers put more emphasis on strategies oriented around comprehension. In many of the lower-income families, the overall orientation tended to be on reading as an exercise, rather than reading for meaning; there was an emphasis on accuracy rather than comprehension and interest. Similar emphasis on print was observed by Goldenberg et al. (1992) in the storybook interactions of low-income Hispanic kindergartners and their parents. Parents gave little attention to the meaning inherent in the storybooks; rather, they focused on the associations of written symbols with their corresponding oral sounds.

It is clear that the majority of experiences children have during shared storybook reading do not involve discussion of the print. This is not meant to imply that storybook reading is of little value for beginning word recognition, but rather that its influence is likely to be more indirect, as in fostering vocabulary knowledge and an interest in learning to read.

Experiences With Educational Books. Use of explicitly educational books, such as ABC books, is likely to promote skills directly related to word recognition. However, use of these books is relatively infrequent. Phillips and McNaughton (1990) asked parents to keep a diary of book reading with their children over the course of 28 days. Only 4.8% of the books that were read were classified as educational (e.g., alphabet books, labeling books, number books). Within the Early Childhood Project, storybooks were read with much greater frequency than were educational books (Baker et al., 1994). Sociocultural differences in the availability of such books were reported by McCormick and Mason (1986): 47% of parents receiving public assistance said they had no alphabet books in the home, whereas only 3% of professional families said they had none.

Summary. Preschool children growing up in literate societies such as the United States have frequent experiences with print. Storybook reading is a common occurrence, especially among middle-income families. However, there is relatively little attention to print during shared storybook reading. More attention occurs when books are read repeatedly or when ABC books are used. In most families, however, ABC books are not used very often in comparison to other types of books. Nevertheless, observations and diary reports of everyday activities show that children have other opportunities to learn about print. These include talking about the print encountered through daily routines such as grocery shopping and practicing writing letters of the alphabet. Parents differ in the relative emphases they place on reading as a source of entertainment and reading as a set of skills to be cultivated; these differing perspectives affect the kinds of literacy opportunities they make available to their children.

Children’s Everyday Home Experiences Involving Rhyme

In addition to providing children with useful knowledge about print, a variety of home experiences might foster the development of phonological awareness. Many people have suggested that children develop phonological awareness through exposure to books with rhymes, to poems, to rhyming verses and songs, and to rhyming language play (e.g., Hannon, 1995; Treiman, 1991). We now consider empirical evidence of such experiences.

Children’s Experiences Involving Rhyme. In the Early Childhood Project, parents of prekindergartners rated frequency of participation in singing, word games, and hand-clap games—activities likely to include rhyme. Parents of all sociocultural groups reported high frequencies of engagement in singing, with a mean rating of 2.44 out of 3. Participation in word games and hand-clap games was relatively infrequent (mean ratings = .83 and 1.02 respectively; Baker et al., 1994).

Sociocultural differences in home experiences related to rhyme have been reported in several different studies. Fernandez-Fein and Baker (1997) found that middle-income families reported that their preschool children had more frequent engagement in word games (usually involving rhyme) than low-income families reported. Marvin and Mirenda (1993) compared the home literacy experiences of low- and middle-income children using a parent survey, and found that a high percentage of all families reported they sang children’s songs (82%), but a higher percentage of parents of children in the middle-income group reported reciting rhymes, poems, or other jingles than did those in the low-income group. Similarly, Elliott and Hewison (1994) found that British middle-class parents of 7-year-olds reported more frequent teaching of nursery rhymes and songs than did working-class parents. In contrast, Raz and Bryant (1990) found no reported differences in exposure to rhymes among low-income and middle-income British preschoolers.

Children are also exposed to rhymes in books, although it does not seem to be a high-frequency event. Parents in the Early Childhood Project were asked whether their children interacted with books that contain rhyme, and 67% noted that, at least occasionally, their child did so. Dickinson et al. (1992) asked mothers of 4-year-old low-income children to read a familiar favorite book to their child, and found that nursery rhyme books were selected just 10% of the time and rhyming/predictable narratives 5%.

Diaries and Observations. Young children often produce rhymes in their own poems and songs. Dowker (1989) studied rhyme and alliteration in poems elicited from a group of socioculturally diverse children between 2 and 6 years of age. She found that 42% of their poems contained rhyme and 26% contained alliteration. Evidence of preschoolers’ language play also comes from Heath’s (1983) ethnographic study. Heath reported that preschool girls in Trackton, a mill town with a large African American population, engaged in older girls’ playsong games. Playsongs included jump-rope songs, hand-clap songs, as well as “made-up” playsongs that accompanied a wide variety of activities. When the older girls read books to their younger siblings (which they did only rarely), they chose alphabet books or nursery rhyme books that lent themselves to sing-song performance. For boys in the community, clever language play involving rhyme and alliteration was highly valued.

Fernandez-Fein and Baker (1997) characterized the rhyme and alliteration experiences of prekindergarten children within the Early Childhood Project as well as a larger sample of middle-income children. Children from diverse sociocultural backgrounds tended to be familiar with a similar set of rhyming routines and songs. Children were not as familiar with tongue twisters, routines that contain alliteration.

The diaries of parents of prekindergarten children in the Early Childhood Project revealed participation in activities that might promote phonological awareness. The most common oral language activity mentioned in the diaries was singing. Another oral activity mentioned by a number of parents was reciting the ABCs. Rhyming activities were specifically mentioned by 10% of the families. These activities involved saying rhyming words, saying or reading nursery rhymes, and reciting poems. In most of these cases, the child initiated the rhyming activity.

Summary. Although we must again be cautious in the conclusions we draw from data based on parental reports, it seems clear that children have frequent exposure to rhyme through singing. However, learning a song that contains rhyming words does not require the same conscious reflection on the sounds of the language as does playing games that require the child to produce rhyming words or words that start with a particular letter of the alphabet. These activities are less common, and there is some evidence from frequency ratings that low-income children experience them less frequently than do middle-income children. On the other hand, ethnographic observations reveal that language play is common among diverse sociocultural groups.

HOW DO CHILDREN’S HOME EXPERIENCES RELATE TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF WORD RECOGNITION SKILLS?

In the previous sections, we presented descriptive information about children’s experiences at home that have the potential to promote the skills needed for word recognition, either directly or indirectly. In this section we consider the effects of specific kinds of experiences on children’s emergent competencies in relevant areas, such as phonological awareness and orthographic knowledge, as well as word recognition per se.

Relations Between Knowledge of the Letters of the Alphabet and Beginning Reading

Many parents believe that part of their role in helping children learn to read is teaching them the letters of the alphabet, and thus they engage in direct instruction of letter names and letter-sound correspondences. Sonnenschein, Baker, and Cerro (1992) asked middle-income mothers of 3- to 5-year-olds to identify specific skills in any domain of development that they were teaching their children at home. The most frequently mentioned skills were emergent literacy skills, which included letter recognition, spelling-sound correspondences, reading, writing letters of the alphabet, and writing; overall, 90% of the mothers mentioned one or more of these skills. The mothers took advantage of the informal educational opportunities afforded by their homes, reporting that they used street signs and food containers to teach the alphabet.

What is the impact of such direct instruction? Not unexpectedly, children who receive instruction from parents in letter naming score higher on tests of letter recognition than do those who have not received such instruction (Hess, Holloway, Price, & Dickson, 1982). Crain-Thoreson and Dale (1992) reported that exposure to instruction in letter-sound correspondences predicted knowledge of print conventions and invented spelling of 4½-year-olds. According to parental reports obtained by Burns and Collins (1987), gifted kindergartners who were early readers had more exposure at home to discussions of letter-sound correspondences, letter names, and word identification experiences than did those who were not early readers.

There is ample evidence that knowing the letters of the alphabet is important for beginning reading, but it is also clear that just teaching children to name the letters of the alphabet is not sufficient (Adams, 1990). What does seem to be important, as Ehri (1984) suggested, is that letter names help children learn to associate phonemes with printed letters. In support of Ehri’s position, children’s letter knowledge in the Early Childhood Project in prekindergarten was significantly correlated with their performance on rhyme detection and rhyme production measured concurrently (Sonnenschein, Baker, Serpell, Scher, Fernandez-Fein, & Munsterman, 1996). In addition, Wagner, Torgesen, and Rashotte (1994) determined that letter-name knowledge exerted a modest causal influence on phonological processing abilities in a longitudinal study of 244 children from kindergarten to second grade. Accuracy of letter naming is not the only important variable; ease or fluency of naming is also important. Walsh, Price, and Gillingham (1988) found that children’s speed of letter naming in kindergarten was strongly related to later progress in reading.

Exposure to Environmental Print and Beginning Word Reading

Does exposure to environmental print facilitate the development of reading? Mason (1980) suggested that reading failure may occur if children do not have experiences with environmental print during the preschool years that help them learn to recognize and name letters. However, there is little empirical evidence of a direct connection. According to parental reports obtained by Burns and Collins (1987), intellectually gifted kindergarten readers and nonreaders had statistically comparable amounts of exposure to environmental print. Masonheimer, Drum, and Ehri (1984) concluded that children who were experts at “reading” environmental print did not pay much attention to the print itself.

It appears that exposure to environmental print alone is unlikely to foster knowledge of individual letters and words unless parents and others explicitly discuss letters and words with children. Rather, environmental print may be valuable in orienting children to print, to the notion that print is meaningful and serves a specific function.

Relations Among Exposure to Rhyme, Phonological Awareness, and Early Reading

It is often assumed that language play helps children develop their rhyme and alliteration skills. Some empirical evidence is available in support of this view (Fernandez-Fein & Baker, 1997; MacLean, Bryant, & Bradley, 1987), but other studies have yielded conflicting evidence (Chaney, 1994; Raz & Bryant, 1990). MacLean et al. (1987) demonstrated in a longitudinal study that there is a relation between children’s knowledge of nursery rhymes and their phonological awareness, as measured by rhyme and alliteration detection and production tasks. Furthermore, knowledge of nursery rhymes and of rhyme and alliteration was related to early reading measured 15 months later. Bryant, Bradley, Maclean, and Crossland (1989) reported that the relations found after 15 months continued to apply over a 3-year period, even after accounting for differences in social background. The authors provided evidence that nursery rhymes enhance children’s sensitivity to rhyme, which in turn helps them learn to read. Although Bryant et al. did not specifically ask parents about their role in fostering knowledge of nursery rhymes, they implied that home experiences were responsible.

Fernandez-Fein and Baker (1997) more directly examined preschool children’s sensitivity to rhyme and alliteration in relation to home experiences as well as nursery knowledge. Participants included 39 prekindergartners in the Early Childhood Project and 20 additional African American and European American middle-income children. Five tasks adapted from MacLean et al. (1987) assessed phonological competencies: rhyme detection, rhyme production, alliteration detection, alliteration production, and nursery rhyme knowledge. Parents provided information about the frequency of their child’s exposure to activities that might foster rhyme and alliteration sensitivity, including word games; hand-clap games; singing; and interactions with storybooks, picture books, educational books, and nonfiction books.

Frequency of participation in word games was significantly correlated with performance on the rhyme detection task (r = .39), the rhyme production task (r = .47), and the nursery rhyme knowledge task (r = .32), suggesting that word games may be important in the development of rhyme sensitivity. Frequency of engagement with books, as indexed by a composite score, was also related to these phonological measures: rhyme detection (r = .47), rhyme production (r = .45), and nursery rhyme knowledge (r = .38). Multiple regression analysis showed that nursery rhyme knowledge accounted for 39% of the variance in sensitivity to rhyme, consistent with the findings of MacLean et al. (1987) and Bryant et al. (1989). Frequency of participation in word games accounted for a significant amount of additional variance (5%), but experiences with books did not.

Information about later progress in word recognition was available for those students who were also participants in the Early Childhood Project (Baker & Mackler, 1997). During prekindergarten as well as kindergarten, children were given the four assessments of phonological awareness as well as the test of nursery rhyme knowledge. They also were given tests of their lowercase and uppercase letter knowledge. In the spring of their second grade year, the Woodcock-Johnson Word Identification test and the Word Attack test were administered to the children as part of a larger assessment battery. We first determined whether prekindergarten or kindergarten performance on the various competency measures was a better predictor of Grade 2 performance on the two outcome measures. The strongest significant predictors on the nursery rhyme tasks, the letter tasks, the rhyme tasks, and the alliteration tasks were then entered into a regression equation. For Word Attack, the predictors were kindergarten nursery rhyme knowledge, kindergarten lowercase-letter knowledge, prekindergarten alliteration detection, and prekindergarten rhyme detection. Nursery rhyme knowledge was the strongest predictor, accounting for 36% of the variance; letter knowledge accounted for an additional 11% of the variance, and alliteration detection 10%. The predictors for Word Identification were kindergarten nursery rhyme knowledge, kindergarten lowercase-letter knowledge, prekindergarten rhyme production, and kindergarten alliteration detection. Once again, nursery rhyme knowledge was the strongest predictor, accounting for 48% of the variance, and letter knowledge contributed an additional 18%.

Interestingly, nursery rhyme knowledge was not a significant predictor of second-grade word recognition when it was assessed in first grade in a different group of children just recruited into the project. Rather, alliteration detection and uppercase-letter knowledge were significant predictors. Nursery rhyme knowledge is based at least in part on children’s home experiences, and other research has suggested that home experiences become less important as children progress through school (Chall, Jacobs, & Baldwin, 1990). These findings are also consistent with the large literature showing the importance of letter knowledge on beginning word recognition.

Chaney (1994) examined relations of home experiences to phonological awareness among 3-year-old children. Family literacy, based on a composite score, was significantly correlated with phonological awareness scores (r = .31), but it did not account for any of the variance in phonological awareness once child age and language development scores were controlled. It is not clear, however, that controlling for language development is appropriate in this context. Moreover, use of a composite measure that included book reading, child interest, library use, and other measures may have masked specific contributions of experiences with rhymes.

Raz and Bryant (1990) examined relations between home experiences, phonological awareness, and early reading. Four- and five-year-old British children from middle-income and low-income families were tested over a period of 18 months, and their mothers were interviewed. Multiple regression analyses using sensitivity to rhyme as the criterion variable and measures of the children’s home experiences as predictor variables revealed that none of the home variables contributed significantly to phonological awareness. That one of the home measures was similar to the word games measure used by Fernandez-Fein and Baker (1997) reflects a failure to replicate. Children’s phonological awareness scores predicted later reading up to 18 months later. Middle-income children were more successful at reading than were low-income children, but the difference between the groups on word recognition were eliminated once differences in phonological awareness were controlled.

Methodological differences among the studies reviewed in this section make it difficult to generalize, but there is at least some evidence that children’s home experiences involving rhyme, including exposure to nursery rhymes and language play, influence children’s sensitivity to rhyme. These experiences are related, either directly or indirectly, to children’s early reading skills.

Relations of Home Reading Activity to Word Recognition Skills

Many studies of home influences on literacy development have explored the effects of shared storybook reading. The government-sponsored report, Becoming a Nation of Readers (Anderson, Hiebert, Scott, & Wilkinson, 1985), emphasized the importance of home storybook reading, with the widely quoted assertion that reading is the single most important thing parents can do to help prepare their children for reading. Indeed, this position goes back as far as the turn of the century, when Huey (1908) wrote, “The secret of it all lies in the parents reading to and with the child” (p. 32).

Two recent syntheses of the literature on the effects of storybook reading concluded that storybook reading accounts for approximately 8% of the variance in outcome measures such as vocabulary development, reading achievement, and emergent literacy (Bus, van IJzendoorn, & Pellegrini, 1995; Scarborough & Dobrich, 1994). Interestingly, Bus et al. interpreted their data as indicative of positive support for the value of storybook reading, whereas Scarborough and Dobrich interpreted their data as indicating that storybook reading really does not contribute as much as has been assumed. Bus et al. were critical of some aspects of the Scarborough and Dobrich synthesis, as were Dunning, Mason, and Stewart (1994) and Lonigan (1994), but all of the researchers concurred that the evidence is not as compelling as one might think given the degree to which storybook reading is promoted.

Relations Between a Focus on Print During Shared Book Reading and Emergent Competencies. Does storybook reading help children develop an understanding of grapheme-phoneme correspondences? Goodman (1986) suggested that with repeated joint storybook reading experience, children come to pay closer attention to the print, noticing correspondences between the words the caregiver is reading and the letters on the page. However, Wells (1986) suggested that the role of storybook reading in enhancing awareness of print and speech may be overestimated. We consider here the evidence related to this issue.

It has proven difficult to detect relations of print-related speech during storybook reading with outcome measures, because so little such speech seems to occur, as we discussed previously. For example, Munsterman and Sonnenschein (1997) were unable to test their hypothesis that the frequency of print-related utterances would predict children’s phonological awareness and knowledge about print because so little such talk occurred. However, Bus and van IJzendoorn (1988) found that the extent to which children focused on print in an ABC book was positively correlated with a variety of emergent literacy measures, including letter-name knowledge, conventions of print, functions of print, and word construction. Attention to the print in the storybook was correlated only with the measure of letter-name knowledge. The extent to which mothers focused on meaning in the ABC book was negatively associated with these emergent literacy measures.

Can knowledge of print be acquired from any story reading experience, or only from story reading interactions that target the print directly? Given that so few interactions do target print directly, the source of such learning must be either incidental or it must occur through other avenues. It is easier to credit incidental learning about the conventions of print (e.g., book handling, directionality) than it is specific knowledge of letters and spelling-sound correspondences. Correlations have been reported between book reading and preschool measures of orthographic knowledge and general concepts about print (e.g., Wells, 1986), but these “may be explained by the fact that families that practice storybook reading also engage in a number of other literacy activities, some of which may be more closely related to these print skills” (Phillips & McNaughton, 1990, p. 211).

Relations Between Frequency of Book Reading and Skills Related to Word Recognition. Relatively few studies have specifically linked home reading activity to word recognition, focusing instead on emergent literacy skills or global reading achievement (Bus et al., 1995; Scarborough & Dobrich, 1994). With respect to component skills, Chaney (1994) found that a composite measure of family literacy predicted 3-year-old children’s alphabet concepts. In the Early Childhood Project, frequency of storybook reading in kindergarten predicted performance on a composite measure of orientation toward print (including letter knowledge, concepts about print, knowledge of the functions and uses of print materials), but not a composite measure of phonological awareness (including rhyme detection, rhyme production, alliteration detection, alliteration production, and nursery rhyme knowledge) assessed in kindergarten (Sonnenschein, Baker, Serpell, Scher, Goddard-Truitt, & Munsterman, 1996). Using an entirely different approach to measuring book reading by first graders, Cunningham and Stanovich (1993) found that print exposure was related to orthographic processing but not phonological awareness (see Cunningham & Stanovich, chap. 10, this volume).

With respect to global reading achievement, Williams and Silva (1985) found that the number of books read to children when they were aged 3 and 5 predicted their reading achievement at age 7, and a similar predictive pattern was reported by Wells (1986). Within the Early Childhood Project, composite measures of total book reading in prekindergarten and kindergarten were significantly correlated with the CTBS comprehension and vocabulary tests in first grade.

Evidence regarding effects of storybook reading on word recognition per se comes from Crain-Thoreson and Dale (1992), who found a relation between frequency of story reading in the home at age 2½ and early word recognition at age 4½. In the Early Childhood Project, reported frequencies of experience with various types of print materials in prekindergarten and kindergarten, including storybooks, were significantly correlated with children’s second-grade scores on the Woodcock-Johnson Word Attack and Word Identification subtests (Baker & Mackler, 1997). However, frequency of looking at educational ABC type books in prekindergarten was the strongest predictor of later scores on both subtests, accounting for 33% and 39% of the variance, respectively. It appears that experience with the more explicitly skills-based books may have greater influence on the development of children’s word recognition skills than does storybook reading. Home experiences with books in Grade 1 were not significant predictors of Grade 2 Word Identification and Word Attack skills, providing additional support for the idea that home experiences have less impact on reading as children grow older.

Summary

Although the database is not abundant, there is evidence that children’s home experiences involving print do help to prepare them for learning to read words in school. Letter names are often explicitly taught by parents, and it is clear that letter knowledge is strongly related to word recognition. When parents and children attend to print during book reading, children show increased knowledge of print. Phonological processing skills are not typically facilitated through direct instruction at home, but reading nursery rhymes to children and playing language games with them help children develop phonological sensitivity.

Storybook reading contributes less than is generally thought to literacy development, probably because initial growth in reading is so heavily dependent on knowledge of letters and phonological awareness, which are not developed by storybook reading. Experience with ABC books is a better predictor of development of skills related to word recognition than storybook reading. However, reading stories to children is important nonetheless, because it affects other dimensions relevant for learning to read, such as fostering interest in reading, vocabulary development, knowledge of story structure, knowledge of the world, and familiarity with the conventions of written language (Baker, in press; Baker et al., 1995).

Caution is needed in interpreting the evidence showing positive effects of storybook reading, because it is usually correlational. As Arnold and White-hurst (1994) suggested, perhaps shared book reading at home is just a marker of parental values or some other factors and the benefits do not come from the book reading itself. For example, the parents may be more educated, they may read more themselves, they may use more sophisticated vocabulary, and so on. As noted earlier, there is considerable evidence of more frequent storybook reading among middle-income families than low-income families, but there are also associated differences in material resources and cultural capital (Lareau, 1989).

Most children, of course, do not learn to read at home, regardless of how much storybook reading parents do with them. It is most common for children to learn to read through formal instruction in school. One reason may be that parents do not engage children in the kinds of activities that move them into independent reading, such as teaching children all of the letter names and promoting phonological awareness through language play. Another reason may be that learning to read in English is not easy. The grapheme-phoneme mapping relations between English print and speech are not transparent, making it difficult for children to discover these on their own.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

A concluding recommendation in Becoming a Nation of Readers (Anderson et al., 1985) is: “Parents should read to preschool children and informally teach them about reading and writing. Reading to children, discussing stories and experiences with them, and—with a light touch—helping them learn letters and words are practices that are consistently associated with eventual success in reading” (p. 117).

Anderson et al. recognized that more than storybook reading is desirable in helping promote reading development at home. However, the key phrase “with a light touch” indicates that they are not recommending a heavily didactic drill-and-practice routine. The phrase “helping them learn” also implies a softer touch; the recommendation is not to teach, but rather to assist the child in what he or she may already have some interest. Parents who see that children are interested in letters and words can provide opportunities for the children to learn more about them in informal playful settings rather than formal schoollike lessons. Middle-income parents are more comfortable with this playful orientation than are lower-income parents (Baker et al., 1995; Baker, Scher, & Mackler, 1997).

Intervention programs that teach low-income and minority parents how to help their children with reading have met with some success (Edwards, 1994). For example, Whitehurst et al. (1988) demonstrated that teaching low-income parents to ask their children questions that extend the meaning of the story is beneficial to children’s vocabulary development. However, many researchers stress the importance of developing reading intervention programs that mesh with parents’ preexisting beliefs (e.g., DeBaryshe, 1995; Goldenberg et al., 1992). This would suggest that home literacy materials and activities should be meaningful to parents within the frames of reference they use to understand how children learn (Baker, Allen, et al., 1996; Thompson, Mixon, & Serpell, 1996).

If storybook reading does not contribute greatly to what children know about letters and sounds, as the available evidence suggests, how then do they acquire this knowledge? Preschoolers frequently ask about signs, labels, and print in the environment. Mere exposure to environmental print does not seem to play a role, as Masonheimer et al. (1984) demonstrated, but children’s questions about environmental print may well be a powerful signal that they are attending to the relevant graphic cues. Another avenue may be in children’s play activities involving print, as when they play with magnetic letters of the alphabet or play “school” with older siblings. Data collected in the Early Childhood Project when the children were in prekindergarten indicate that such activities occur regularly in many families. Writing also is a powerful mechanism for learning letter-sound correspondences and is also a common recurrent activity. And, of course, direct instruction of alphabet letter names and sounds is a potent avenue of learning.

What, then, should be the role of parents regarding early literacy? Should they teach their children to read? Might their efforts interfere with rather than facilitate children’s development as readers? Parents who emphasize the skills that are important to word recognition at the expense of enjoyable storybook reading focused on meaning may convey a picture of reading as dull and lifeless that stays with the child long after school entry. There are many things parents can do to prepare children for the instruction they will receive in school that stop short of reading instruction per se. They can regularly read books to their children and they can illustrate through their own actions that reading is useful and enjoyable. They can teach children to name and write letters in a playful manner, drawing on educational toys, television, and computer software if such resources are available. They can play with sounds in words in ways that promote sensitivity to rhyme, alliteration, and phonemic awareness. Parents should not try to teach their child to read unless the child leads the way.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Preparation of this chapter and some of the research described in it was supported in part by the National Reading Research Center of the Universities of Georgia and Maryland and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (principal investigators Linda Baker, Susan Sonnenschein, and Robert Serpell), and by a National Science Foundation graduate fellowship to Sylvia Fernandez-Fein. We deeply appreciate the contributions of our other colleagues on the Early Childhood Project: Robert Serpell, Susan Sonnenschein, Hibist Astatke, Evangeline Danseco, Marie Dorsey, Victoria Goddard-Truitt, Linda Gorham, Susan Hill, Kirsten Mackler, Tunde Morakinyo, Kim Munsterman, Diane Schmidt, and Sharon Teuben-Rowe. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this chapter are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Reading Research Center, the Office of Educational Research and Improvement, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, or the National Science Foundation.

Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Anderson, R. C., Hiebert, E. H., Scott, J. A., & Wilkinson, I. A. (1985). Becoming a nation of readers: The report of the commission on reading. Champaign, IL: National Academy of Education, Center for the Study of Reading.

Anderson, A. B., & Stokes, S. J. (1984). Social and institutional influences on the development and practice of literacy. In H. Goelman, A. A. Oberg, & F. Smith (Eds.), Awakening to literacy (pp. 24–37). London: Heinemann.

Arnold, D. S., & Whitehurst, G. J. (1994). Accelerating language development through picture book reading: A summary of dialogic reading and its effects. In D. K. Dickinson (Ed.), Bridges to literacy: Children, families, and schools (pp. 103–128). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Baker, L. (in press). Opportunities at home and in the community that foster reading engagement. In J. T. Guthrie & D. E. Alvermann (Eds.), Engagement in reading: Processes, practices, and policy implications. New York: Teachers’ College Press.

Baker, L., Allen, J. B., Shockley, B., Pellegrini, A. D., Galda, L., & Stahl, S. (1996). Connecting school and home: Constructing partnerships to foster reading development. In L. Baker, P. Afflerbach, & D. Reinking (Eds.), Developing engaged readers in school and home communities (pp. 21–41). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Baker, L., & Mackler, K. (1997, April). Contributions of children’s emergent literacy skills and home experiences to Grade 2 word recognition. In R. Serpell, S. Sonnenschein, & L. Baker (Chairs), Patterns of emerging competence and sociocultural context in the early appropriation of literacy. Symposium presented at the meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Washington, DC.

Baker, L., Scher, D., & Mackler, K. (1997). Home and family influences on motivations for reading. Educational Psychologist, 32, 69–82.

Baker, L., Serpell, R., & Sonnenschein, S. (1995). Opportunities for literacy learning in the homes of urban preschoolers. In L. M. Morrow (Ed.), Family literacy: Connections in schools and communities (pp. 236–252). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Baker, L., Sonnenschein, S., Serpell, R., Fernandez-Fein, S., & Scher, D. (1994). Contexts of emergent literacy: Everyday home experiences of urban pre-kindergarten children (Research Report #24). Athens, GA: National Reading Research Center, Universities of Georgia and Maryland.

Baker, L., Sonnenschein, S., Serpell, R., Scher, D., Fernandez-Fein, S., Munsterman, K., Hill, S., Goddard-Truitt, V., & Danseco, E. (1996). Early literacy at home: Children’s experiences and parents’ perspectives. The Reading Teacher, 50, 70–72.

Bryant, P. E., Bradley, L., MacLean, M., & Crossland, J. (1989). Nursery rhymes, phonological skills and reading. Journal of Child Language, 16, 407–428.

Burns, J. M., & Collins, M. D. (1987). Parents’ perceptions of factors affecting the reading development of intellectually superior accelerated readers and intellectually superior nonreaders. Reading Research and Instruction, 26, 239–246.

Bus, A. G., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (1988). Mother-child interactions, attachment, and emergent literacy: A cross-sectional study. Child Development, 59, 1262–1272.

Bus, A. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (1995). Mothers reading to their 3-year-olds: The role of mother-child attachment security in becoming literate. Reading Research Quarterly, 30, 998–1015.

Bus, A. G., van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Pellegrini, A. D. (1995). Joint book reading makes for success in learning to read: A meta-analysis on intergenerational transmission of literacy. Review of Educational Research, 65, 1–21.

Chall, J. S., Jacobs, V. A., & Baldwin, L. E. (1990). The reading crisis: Why poor children fall behind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard.

Chaney, C. (1994). Language development, metalinguistic awareness, and emergent literacy skills of 3-year-old children in relation to social class. Applied Psycholinguistics, 15, 371–394.

Crain-Thoreson, C., & Dale, P. S. (1992). Do early talkers become early readers? Linguistic precocity, preschool language, and emergent literacy. Developmental Psychology, 28, 421–429.

Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1993). Children’s literacy environments and early word recognition subskills. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 5, 193–204.

DeBaryshe, B. D. (1995). Maternal belief systems: Linchpin in the home reading process. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 16, 1–20.

Dickinson, D. K., DeTemple, J. M., Hirschler, J. A., & Smith, M. W. (1992). Book reading with preschoolers: Coconstruction of text at home and at school. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 7, 323–346.

Dowker, A. (1989). Rhyme and alliteration elicited from young children. Journal of Child Language, 16, 181–202.

Dunning, D. B., Mason, J. M., & Stewart, J. P. (1994). Reading to preschoolers: A response to Scarborough and Dobrich (1994) and recommendations for future research. Developmental Review, 14, 324–339.

Durkin, D. (1966). Children who read early. New York: Teachers’ College Press.

Edwards, P. A. (1994). Responses of teachers and African American mothers to a book reading intervention program. In D. K. Dickinson (Ed.), Bridges to literacy: Children, families, and schools (pp. 175–208). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Ehri, L. C. (1984). How orthography alters spoken language competencies in children learning to read and spell. In J. Downing & R. Valtin (Eds.), Language awareness and learning to read (pp. 119–147). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Elliott, J. A., & Hewison, J. (1994). Comprehension and interest in home reading. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 64, 203–220.

Fernandez-Fein, S., & Baker, L. (1997). Rhyme and alliteration sensitivity and relevant experiences in preschoolers from diverse backgrounds. Journal of Literacy Research, 29, 433–459.

Goldenberg, C., Reese, L., & Gallimore, R. (1992). Effects of literacy materials from school on Latino children’s home experiences and early reading achievement. American Journal of Education, 100, 497–536.

Goodman, Y. (1986). Children coming to know literacy. In W. H. Teale & E. Sulzby (Eds.), Emergent literacy: Writing and reading (pp. 1–14). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Guthrie, J., & Greaney, V. (1991). Literacy acts. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. II, pp. 68–96). New York: Longman.

Hannon, P. (1995). Literacy, home, and school. Bristol, PA: Falmer.

Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Hess, R. D., Holloway, S., Price, G. G., & Dickson, W. P. (1982). Family environments and acquisition of reading skills: Toward a more precise analysis. In L. M. Laosa & I. Sigel (Eds.), Families as learning environments for children (pp. 87–113). New York: Plenum.

Huey, E. B. (1908). The psychology and pedagogy of reading. NY: Macmillan.

Lareau, A. (1989). Home advantage: Social class and parental intervention in elementary education. London: Falmer.

Lonigan, C. J. (1994). Reading to preschoolers exposed: Is the emperor really naked? Developmental Review, 14, 303–323.

MacLean, L., Bryant, P., & Bradley, L. (1987). Rhymes, nursery rhymes, and reading in early childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 33(3), 255–281.

Marvin, C., & Mirenda, P. (1993). Home literacy experiences of preschoolers enrolled in Head Start and special education programs. Journal of Early Intervention, 17, 351–367.

Mason, J. (1980). When do children begin to read?: An exploration of four-year-old children’s letter and word reading competencies. Reading Research Quarterly, 15, 203–227.

Masonheimer, P. E., Drum, P. A., & Ehri, L. C. (1984). Does environmental print identification lead children into word reading? Journal of Reading Behavior, 16, 257–271.

McCormick, C. E., & Mason, J. M. (1986). Intervention procedures for increasing preschool children’s interest in and knowledge about reading. In W. H. Teale & E. Sulzby (Eds.), Emergent literacy: Writing and reading (pp. 90–115). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Morrow, L. M. (1988). Young children’s responses to one-to-one story readings in school settings. Reading Research Quarterly, 23, 89–107.

Morrow, L. M. (1989). Literacy development in the early years. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Munsterman, K. A., & Sonnenschein, S. (1997, April). Qualities of storybook reading interactions and their relations to emergent literacy. In R. Serpell, S. Sonnenschein, & L. Baker (Chairs), Patterns of emerging competence and sociocultural context in the early appropriation of literacy. Symposium presented at the meetings of the Society for Research in Child Development, Washington, D.C.

Pellegrini, A. D., Perlmutter, J. C. Galda, L., & Brody, G. H. (1990). Joint book reading between black Head Start children and their mothers. Child Development, 61, 443–453.

Phillips, G., & McNaughton, S. (1990). The practice of storybook reading to preschoolers in mainstream New Zealand families. Reading Research Quarterly, 25, 196–212.

Raz, I. T., & Bryant, P. (1990). Social background, phonological awareness and children’s reading. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 8, 209–225.

Scarborough, H. S., & Dobrich, W. (1994). On the efficacy of reading to preschoolers. Developmental Review, 14, 245–302.

Senechal, M., LeFevre, J., Hudson, E., & Lawson, E. P. (1996). Knowledge of storybooks as a predictor of young children’s vocabulary. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 520–536.

Serpell, R., Sonnenschein, S., Baker, L., Hill, S., Goddard-Truitt, V., & Danseco, E. (1997). Parental ideas about development and socialization of children on the threshold of schooling (Reading Research Report #78). Athens, GA: Universities of Georgia and Maryland, National Reading Research Center.

Snow, C. E. (1994). Enhancing literacy development: Programs and research perspectives. In D. K. Dickinson (Ed.), Bridges to literacy: Children, families, and schools (pp. 267–272).

Cambridge, MA: Blackwell. Snow, C. E., Barnes, W. S., Chandler, J., Goodman, I. F., & Hemphill, L. (1991). Unfulfilled expectations: Home and school influences on literacy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sonnenschein, S., Baker, L., & Cerro, L. (1992). Mothers’ views on teaching their preschoolers in everyday situations. Early Education and Development, 3, 1–22.

Sonnenschein, S., Baker, L., Serpell, R., Scher, D., Fernandez-Fein, S., & Munsterman, K. A. (1996). Strands of emergent literacy and their antecedents in the home: Urban preschoolers’ early literacy development (Reading Research Report #48). Athens, GA: Universities of Georgia and Maryland, National Reading Research Center.

Sonnenschein, S., Baker, L., Serpell, R., Scher, D., Goddard-Truitt, V., & Munsterman, K. (1996, August). The relation between parental beliefs about reading development and storybook reading practices in different sociocultural groups in Baltimore. Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development, Quebec City.

Sonnenschein, S., Baker, L., Serpell, R., Scher, D., Goddard-Truitt, V., & Munsterman, K. (1997). Parents beliefs about ways to help children learn to read: The impact of an entertainment or a skills perspective. Early Child Development and Care, 127–128, 111–118.

Sonnenschein, S., Brody, G., & Munsterman, K. (1996). The influence of family beliefs and practices on children’s early reading development. In L. Baker, P. Afflerbach, & D. Reinking (Eds.), Developing engaged readers in school and home communities (pp. 3–20). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sulzby, E., & Teale, W. (1991). Emergent literacy. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. II, pp. 727–758). New York: Longman.

Taylor, D., & Dorsey-Gaines, C. (1988). Growing up literate: Learning from inner city families. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Teale, W. H. (1986). Home background and young children’s literacy development. In W. H.

Teale & E. Sulzby (Eds.), Emergent literacy: Writing and reading (pp. 173–205). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Thompson, R., Mixon, G., & Serpell, R. (1996). Engaging minority students in reading: Focus on the urban learner. In L. Baker, P. Afflerbach, & D. Reinking (Eds.), Developing engaged readers in school and home communities (pp. 43–63). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Treiman, R. (1991). Phonological awareness and its roles in learning to read and spell. In D.J. Sawyer & B. J. Fox (Eds.), Phonological awareness in reading: The evolution of current perspectives (pp. 159–189). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Wagner, R. K., Torgesen, J. K., & Rashotte, C. A. (1994). The development of reading-related phonological processing abilities: New evidence of bi-directional causality from a latent variable longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 30, 73–87.

Walsh, D. J., Price, G. G., & Gillingham, M. G. (1988). The critical but transitory importance of letter naming. Reading Research Quarterly, 23, 108–122. Wells, G. (1986). The meaning makers: Children learning language and using language to learn. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Whitehurst, G. J., Falco, F. L., Lonigan, C. J., Fischel, J. E., DeBaryshe, B. D., Valdez-Menchaca, M. C., & Caulfield, M. (1988). Accelerating language development through picturebook reading. Developmental Psychology, 24, 552–559.

Williams, S. M., & Silva, P. A. (1985). Some factors associated with reading ability: A longitudinal study. Educational Research, 27, 159–168.

Yaden, D. B., Smolkin, L. B., & Conlon, A. (1989). Preschoolers’ questions about pictures, print conventions, and story text during reading aloud at home. Reading Research Quarterly, 24, 188–213.