![]()

Phonics and Phonemes: Learning to Decode and Spell in a Literature-Based Program

Robert Calfee

Stanford University

This chapter is written in a context of turmoil within California and elsewhere, as concerned parents and legislators demand a shift from literature-based early literacy programs to “old-fashioned” phonics and spelling. Low test scores (real or purported) are one cause for California’s concerns, but similar efforts are welling up in other states. The conflict reflects deep underlying issues, some political, others personal, about the goals of education.

This conflict is probably as divisive in early literacy as anywhere in the curriculum: phonics versus literature, skill versus understanding, passive practice versus eager engagement. In one view, early schooling should inculcate basic skills by teacher-led direct instruction. Virtually all phonics programs incorporate this method (Adams, 1990—note that the citations in this chapter are minimal, mostly as leads to the relevant archival literature; for additional background, see Calfee & Drum, 1986; Calfee & Henry, 1996). From another perspective, the aim is for students to become strategic and purposeful, capable of teamwork as well as individual excellence. Whole language reflects this philosophy, as have predecessors (e.g., Ashton-Warner, 1963; Mclntyre & Pressley, 1996; Weaver, 1990). One additional contrast merits comment: the belief that young students differ substantially in their innate capacity to acquire literacy versus the belief (and commitment) that all children are capable of achieving high levels of literacy, regardless of their background and experience.

This chapter describes a framework that incorporates the most promising features of the contrasting positions, not by simple “addition,” but by a redesign that goes beyond existing policies and practices. One strategy for achieving balance is to spend part of each reading lesson on standard phonics, and then switch to literary appreciation. This approach to eclecticism, which typifies many classrooms, lacks coherence and is of uncertain effectiveness. Another strategy is a gradual shift over the grades from basics to “the real stuff”—phonics in first grade, comprehension skills by third grade. Both strategies can be found in classrooms and in the basal series that remain the foundation for reading instruction in U.S. schools. If balance means eclecticism, then we have tried it for several decades, and it apparently does not work for many students.

To concretize the current dilemma, imagine a primary (K–2) team of teachers who ask a consultant how they can sustain the advantages of a literature-based program while ensuring that their students acquire skills needed for independent reading and writing. Their literature-based approach motivates students, but a substantial number of students are eager to read but unable to decode unfamiliar words, willing to write but unable to spell words well enough to read them a week later. The teachers worry about two specific phonics issues. First, many students show little interest in learning to decode and spell; they prefer books that they “already know how to read.” Second, many students acquire phonics objectives slowly, retention and transfer are limited, and the activities are monotonous. The teachers have adopted a supplemental decoding program. Now they are discussing whether to increase instruction time in phonics, or perhaps assign more students to intensive remediation.

For the past several years I have been “tinkering” with an alternative to these currently available practices; Word Work is a decoding-spelling strand incorporating the policies and practices found in literature-based classrooms (Calfee & Patrick, 1995). The program features include the creation of a “literate community” consistent with whole language philosophy, but with a greater emphasis on explicit strategies for literature analysis, and with a complementary emphasis on teaching students explicit strategies for analysis of English spelling–sound relations.

Word Work differs from typical phonics programs in several ways. First, instruction incorporates principles of social-cognitive learning; instruction is student centered more than teacher directed. Students encounter “real” spelling tests as they revise a work for public display, but they can ask others for help in polishing the work. Second, spelling–sound relations are taught as a meaningfully organized system rather than a list of rote objectives. The program incorporates the metaphonic principle: Students are expected to give the correct pronunciation or spelling, but also to explain how they reached it. Third, decoding and spelling are integrated, emphasizing immediate application in purposeful reading and writing. Unlike a step-by-step model by which students first learn to read, Word Work students progress in parallel across all domains of reading and writing. Finally, although teachers highlight spelling–sound patterns in reading selections and writing assignments, neither reading nor writing is limited by the decoding-spelling curriculum. Students may be working on short-vowel patterns, but this does not confine them to “The fat cat sat on the flat mat.”

This chapter describes the Word Work program and presents three case studies. The results are that virtually all students acquired the decoding-spelling skills and understanding needed for independent reading and writing in a literature-based program. The program does challenge classroom teachers, because it requires going beyond both free-form literature-based activities and lockstep phonics prescriptions.

THE PHONICS DEBATE: WHAT TO TEACH AND HOW TO TEACH IT

This volume is set against the continuing debate about reading and writing instruction during the first 3 years of schooling. Here are some observations about what we already know and have yet to discover, based on research and practice (Adams, 1990; Chall, 1983; Chall, Jacobs, & Baldwin, 1990):

Explicit phonics: A traditional phonics curriculum improves early reading as measured by standardized achievement tests, compared with programs that do not include explicit decoding-spelling. Unfortunately, 15% to 35% of phonics-taught students still reach third grade unable to handle grade-level reading and writing tasks. Most research relies on multiple-choice tests; few large-scale evaluations have assessed reading fluency, spelling and writing performance, interest, or motivation.

Phonemic awareness: Students’ ability to identify and manipulate speech sounds on entry to school is a strong predictor of success in acquiring literacy, and instructional programs that incorporate phonemic awareness help students, especially those at risk for learning to read. Unfortunately, the construct of phonemic awareness remains fuzzy, with multitudinous definitions and programs of uncertain effectiveness.

Comprehension and composition: Skill and knowledge in handling texts are not an automatic consequence of learning to decode and spell. Immersion in genuine literature and informational books, opportunities to reread familiar stories, and purposeful writing all increase interest in reading, enhance general text knowledge, and expand word knowledge.

Missing from this list is any answer to the question of what to teach. It is assumed throughout the debate that phonics is clearly defined. The job is simply to teach letter-sound relations. Letters are easy to see, and phonemic awareness helps students learn about sounds. What’s the problem?

In fact, as the following section shows, the English letter-sound system is a rather remarkable invention, and understanding this system is crucial for the construction of a comprehensible curriculum. The conceptual framework for Word Work builds on the historical and morphophonemic structure of English orthography (Balmuth, 1982; Venezky, 1970), which leads in turn to a definition of phonemic awareness and an explanation for its importance in acquiring phonics. Both the incidental mini-lessons of whole language and the overly specific objectives of the phonics curriculum obscure this structure, confusing students and teachers.

English: A Truly Alphabetic Language

English is a polyglot—many languages. Anglo-Saxon is the foundation, with overlays of French from the 11th-century Norman invasion, Latin and Greek from the English Renaissance, and contributions from around the world reflecting the military and economic dominance of the British (and later) the Americans. Anglo-Saxon, the basis for 95% of the most frequent words, is a collage of languages from the Baltic regions. With origins in German and Swedish, Anglo-Saxon took on a character of its own as successive waves of invaders swept over England, beginning in 200 AD with the Angles and Saxons, continuing with the Vikings and Jutes. Oral traditions dominated during this time. Languages melded and merged, creating an amalgam shaped around a small lexicon of “four-letter” words, with compounds serving for complex constructs. The language was phonetically rich, with multiple dialects.

Catholic missionaries created a written form of Anglo-Saxon-ish using the Roman alphabet. Twenty-four letters were a poor match to 40-plus phonemes, with vowels a particular challenge. In 1066, the Normans complicated matters by adding some 50,000 new words to the Anglo-Saxon base. The English gutturalized the French pronunciation, but print remained fixed, adding a second spelling system to the emerging written language. Romance words were used for more formal discourse—clam for plain language, mollusk for fancy. Around third grade, today’s students begin to encounter these fancy words. This chapter focuses on the Anglo-Saxon orthography that children confront in the primary grades; Romance words will require their own tale.

English orthography is fundamentally alphabetic. Letters represent sounds, although not by simple linear translation. Graphemes, the sound-bearing elements, can be letter combinations like sh or ps. In a word like lampshade, linear reading might yield /lamps-ha-de/—close, but no cigar. Accomplished readers first divide the word into its morphemes or word parts. They can then divide each morpheme into graphemic units; m and p are two different units, whereas sh is a single unit. Consonants are relatively simple, but vowels are a mess. Anglo-Saxon relies heavily on markers to signal vowel contrasts. In the present example, the final e acts not as a sound in its own right (although at one time it did), but indicates the “long” pronunciation of the preceding a.

Simple “rules” will not work, and educators despair at complexity. There is a simple solution. For the young student, learning to decode and spell depends on sorting words into three categories. The first set, handy words, comprises the high-frequency words (the Dolch list) essential for all reading and writing. Many are function words like the, a, is, was, of, and on, which provide the semantic “glue” for making sentences. They often depart from regular letter-sound patterns. The second set, topical words, serves for particular tasks, such as writing about the fall holidays—Halloween, Thanksgiving, and the winter solstice (Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanza)—which requires a rich array of words, many long and complex, reflecting the many languages and cultures in our nation. In the third set, words are regular, in the sense that they follow predictable patterns. They are not especially frequent, nor are they related to any particular topic. Handling these words requires that students be able to “attack” the enormous array of words within their spoken language (although perhaps unknown in print). The foundation for this third set is the consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) “sandwich,” the centerpiece of the Word Work curriculum.

The CVC unit is a user-friendly label for the vocalic center unit that linguists have identified as a fundamental unit in English orthography. In many languages, the contrast between vowels and consonants is not essential for understanding orthographic patterns. Spanish, for instance, relies on unitized consonant-vowel combinations—ma-me-mi-mo-mu—much like the syllabaries in languages like Japanese. What distinguishes English is the huge number of CVC combinations, more than 50,000, that arise from its rich array of consonants, consonant digraphs, and consonant blends, combined with the multitude of vowel patterns (Fig. 13.1). These basic building blocks appear as individual words (tab, fit), and within syllabic patterns (rabbit) and morphological combinations (hotshot). The student who has learned to process these patterns as unitized chunks can decode and spell an enormous variety of novel words in print.

Two challenges confront the developing reader in mastering the chunking task. The first is to acquire the concept of the CVC unit. The second is to master vowel correspondences. The Word Work curriculum focuses on these two primary elements.

The CVC Building Block

English is “truly alphabetic.” What does this claim mean, and why is it important? The alphabetic principle describes an array of spelling systems in which graphemes represent phonemes. Sometimes the correspondence is fairly simple and consistent; each grapheme represents a single phoneme. The connection is seldom perfect, of course, because variations in oral speech appear in every language. In English, for example, “What you just said” often comes out as “Wha-chue-ju-sed.” In contrast, one can speak understandable Spanish by reading consonant-vowel combinations.

FIG. 13.1. Consonant-vowel matrix for Anglo-Saxon letter-sound correspondences.

English, although fundamentally alphabetical, has numerous surface-level complexities and inconsistencies. Some educators, partly because of these irregularities, and partly from laboratory research on whole-word recognition by skilled readers, conclude that the best way to teach English print is through extensive practice with the word as the unit of analysis: “Just read!” Such “Chinese” readers can be found, but their skill level is typically lower than that of so-called “Phoenician” readers, who have mastered letter-sound relations. Experienced readers can process individual letter-sound units in a word, and rely on this technique when confronted with novel or complex words, sometimes for decoding but especially for spelling.

Phonics programs generally build on some form of syllabary. One strategy is to teach phonogram patterns, consonant + vowel/consonant combinations, in which an initial consonant is added to the phonogram base (r-at, f-at, m-at). Studies show that these onset + rime patterns are more easily acquired than the alternative consonant/vowel + consonant combinations (ra-n, ra-t, ra-d), at least for English.

Neither whole-word nor phonogram-analogy methods require students to operate at the level of individual phoneme-grapheme relations, except perhaps for initial consonants. Curiously, although consonants exist in greater numbers and are phonologically more complex than are vowels, several decades of research show that vowels are most problematic in early decoding and spelling.

The argument for treating English as “truly alphabetic” rests on the large number of CVC building blocks that appear not only as words but as patterns. Learning these patterns is important if students are to gain independent access to literature. Flipping through my worn copy of Frederick’s fables (Lionni, 1994), I encounter words like abandon, reproachful, periwinkle, and scatters. These words are all built of CVC “chunks”; understanding these units can open the door for the young reader to a marvelous collection of stories, even to writing periwinkle if she wishes.

Mastering the concept of the CVC “sandwich” is fundamental if the early reader is to handle novel words in reading and writing. Acquiring this concept means understanding the functional difference between consonants (the primary information-bearing units) and vowels (the “glue” that binds the consonants).

Phonemic Awareness as Articulation

Phoneme awareness is important because of the enormous number of CVC combinations in English, mentioned earlier. The gist of the present argument is that (a) full understanding of the alphabetic principle is critical for efficient decoding and spelling of CVC patterns, (b) explicit knowledge of phonemic elements is necessary for students to have something to link to graphemes, and (c) the articulatory dimensions of the consonant system provide the basis for teaching students about phonemes.

Like the alphabetic principle, the concept of phonemic awareness has been defined in various ways (Share, 1995). The most common definition in U.S. schools is “listen for the sounds in a word.” This is actually a tough job! It takes considerable insight to know for what to listen. The kindergartner asked to mark all the words that “begin like bat” may chose ball for the wrong reason and mark spot for the right reason. Elkonin’s (1963) early work emphasized the capacity to identify the number of phonemes in a spoken word: fox has four elements, as does shucks. A few programs, most notably Lindamood’s Auditory Discrimination in Depth, teach articulation patterns. At the most basic level, the student is taught to lay out a string of colored blocks to mark the number and patterning of elements; fox can be written as red-yellow-blue-green, and shucks as orange-purple-blue-green.

A crucial element in Word Work is the development of explicit understanding of the concept of a “sound,” to which the key is not listening ability but speech perception. It is not enough to distinguish syllables and rhymes, although these are useful indicators and it helps students to know these concepts. Instead, the critical feature for English orthography is the phoneme, the set of subtle and complex distinctions that mark the contrasts among bat, pat, and bad. The motor theory of speech perception (Brady & Shank-weiler, 1991) suggests that articulation (how phonemes are produced) is the key to perception (how phonemes are heard).

Word Work goes directly to the phoneme-grapheme level. Students are taught individual letter-sound relations for the consonants through the articulatory principle, using the dimensions of manner, place, and voicing. For example, the phoneme typically represented by f is produced by placing the upper teeth on the lower lip and “hissing.” The phoneme represented by v is made the same way, but the vocal cords are activated slightly before the sound is released. The second step in the decoding-spelling process occurs when students learn to make CVC “sandwiches,” in which they “glue” two consonants together with a vowel. The quote marks are intentional; vivid language around familiar terms helps students (and teachers) understand abstract constructs.

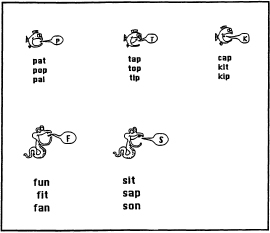

Articulatory features come into play in two ways when learning to decode and spell. First is the idea that an English grapheme directs the reader how to produce a sound. In Word Work, this concept is introduced through seven primary consonant phonemes—p, t, clk, f, s, m, n—that are taught in parallel to emphasize the dimensions of manner and place. The first three are stop consonants, the next two are fricatives, and the last two are nasals. Introducing this collection as an organized matrix (Fig. 13.2) supports conceptual insight rather than the rote learning that occurs when correspondences are taught in isolation.

Second, articulation is used to guide production of complete CVC units and to monitor the accuracy of the production. In reading fat, for instance, students do not say /fuh-a-tuh/, but /f-a-t/. The teacher models the process of thinking in advance about what the mouth is going to do during the production, and then directs students to check what actually happens as the word is being said. Pronunciation is “stretched out” by elongating the vowel, allowing time for students to focus on each phonological unit.

Spelling CVC units reverses this process. In thinking about how to spell /pan/, for instance, students pronounce the word once or twice, stretching out the vowel and focusing on the consonant articulation. They can see the PTK matrix for visual clues about the relation between articulatory features and the corresponding letters. Spelling is a verbal task during Word Work lessons: “How do you spell /sam/?” “S-A-M.” “Check it out! Say /sam/ again and feel what your mouth does.”

FIG. 13.2. Sample matrix for students displaying articulatory dimensions of place and manner for seven initial consonants in Word Work “Making Sounds.”

Reliance on articulation and “stretching” has a direct bearing on the temporal dimension of decoding and spelling. Children identified as “reading disabled” are often described as having “auditory processing” difficulties. They have problems tracking the order of events in a sequence. In fact, analyzing the sequence of sounds in a word is an auditory challenge for everyone. Within a matter of half a second, as a brief part of a much longer and far more complicated sequence, the listener must translate blend into “voiced-front-stop + middle-labial-semi-vowel + middle-vowel + middle-nasal + voiced-middle-stop.” Normal communication does not require this level of detail, but the reader/writer, confronting blend in the midst of a more extended text, faces exactly this challenge—how to convert the graphemes into a reproducible sequence. On the flip side, the student who wants to write about his or her “blended family” must convert the word into a phonemic sequence to which graphemes can be attached in the proper order.

In normal speech, we give little attention to the temporal dimension—we just “talk.” Instructing students about the articulatory dimensions of speech gives them control over the temporal dimension. They can stretch out the elements of a word so that each element takes a distinctive shape, while preserving the “whole.” This conceptualization of phonemic awareness is distinctive in several ways from most existing alternatives. First, it has little in common with the strategy of teaching that cat is /kuh-a-tuh/. Although this portrayal may serve some purposes, it is linguistically bizarre, and ineffective as an instructional technique. On the other hand, the student who reads cat and can then describe the shift from one phonemic element to the next possesses strategies of considerable power for decoding and spelling unfamiliar words. Second, the focus is on production more than perception, on how a sound is constructed rather than on “listening more carefully.” Third, it emphasizes the structure of the phonemic system rather than specific objectives. The large number of phonemes and phoneme combinations in the English language is a tempting target for behavioral analysis—sufficient objectives to keep a class busy for the better part of the school year, but unfortunately leaving little time for “real” reading and writing.

Word Work helps students grasp the basic dimensions of the phoneme system—quickly—to support productive and independent engagement with print. Research suggests that the interplay between phonemic awareness and acquisition of the concept of letter-sound correspondences is synergistic (cf. Stahl & Murray, chap. 3, this volume; also Bentin & Leshem, 1993). For the child approaching the acquisition of written English, learning rhymes and studying the ABCs is undoubtedly a good thing, but it does not guarantee the type or level of phonemic awareness needed to grasp the alphabetic principle at the level of complex letter-sound correspondences. Explicit instruction on phonemic awareness, however construed, is most effective when directly coupled with the learning of letter-sound relations, and the sooner the better.

Word Work treats consonants and vowels as different phonemic categories: consonants are taught by guiding students to understand their articulatory structure; vowels are taught to be the “glue” that connects consonants; and CVCs serve as “lego pieces” to form more complex words, either by conjoining these basic building blocks into polysyllabic constructions (porridge, potage), or by combining base morphemes into compounds (potpie, potter).

A MODEL OF CURRICULUM DESIGN FOR EARLY LITERACY

This section of the chapter describes the development of an early literacy program built around the preceding principles, a program that begins with a “story strand” grounded in children’s literature, but that also includes a separate and explicit “word strand” for decoding and spelling skills. The complete program, Project READ Plus (Calfee & Patrick, 1995), takes shape not as a collection of prepackaged materials, but as a professional development activity that provides teachers with concepts, structures, and strategies that allow them to make informed decisions about what to teach and how to teach it in order to promote critical literacy—the capacity to use language to think and communicate.

All facets of the program are designed to support professional development in the following ways. First, the strands build on a common set of undergirding principles about learning, language, and literacy, a conceptual framework that provides teachers a foundation for justifying instructional decisions. Teachers often rely on implicit theories about students; READ Plus offers explicit and practical theories and methods.

Second, the strands are separable. Separability must be disciplined; the key is to find the right way to carve a complex task into a small number of distinctive chunks. By focusing on specific chunks, students can grasp the structure that undergirds a domain, and acquire the technical vocabulary for the entire domain. It is also important to link the parts to the whole. In virtually every human endeavor, expertise is not a matter of “part,” “whole,” “part-to-whole,” or “whole-to-part,” but instead comprises informed decisions about when and how to employ these strategies.

Third, all strands are inherently developmental. The same basic structures and strategies apply across all grades, with content and depth dependent on students’ developmental level and interests. Many states and districts assign different stories to each grade. Charlotte’s Web can be appropriate for any grade level. Kindergartners will appreciate this story in one way, whereas fourth graders see in it a deeper truth about how antagonists can become intimates.

Fourth, every strand emphasizes organization, productivity, and transferable knowledge and skills. These criteria contrast sharply with the microde-composition typical of objectives-based programs, in which teachers and students are confronted with hundreds of piecemeal outcomes, every objective is allotted time regardless of the pay-off, and learning often disappears after it is tested. In READ Plus, the emphasis is on a small number of high-level outcomes justified by the criteria of coherence (they complement one another), breadth of application, and metacognitive potential—outcomes that span kindergarten through adulthood.

The Phonics “Part”

The program described here, Word Work, is an integrated decoding-spelling program designed for students from kindergarten through second grade. The program combines strengths of whole language and basic skills approaches, but has advantages over both. It is based on the metaphonic principle: learning to decode and spell by understanding letter-sound relations rather than by rote practice. The curriculum emphasizes conceptual understanding; instruction is active, social, and reflective, including both direct instruction and small-group problem solving. Part of each day is spent studying letter-sound patterns, based not on a text but instead on a collection of word patterns. Practice and assessment are then grounded in text-based reading and writing.

The Word Work curriculum covers the major Anglo-Saxon spelling patterns: consonants, consonant blends and digraphs, short and long vowels, vowel digraphs, and complex words. It is laid out in an explicit sequence: phoneme awareness and single consonants, short vowels, and long vowels. The program is designed as a component of READ Plus, but can stand alone. It complements most basals and supplementary phonics packages. It is difficult to adapt to strictly linear scope-and-sequence methods. Although compatible with literature-based methods, Word Work uses word collections rather than stories designed around restricted spelling patterns.

The Curriculum Chart. The left-hand panel of Fig. 13.3 displays the primary strand of Word Work as a classroom chart. The idea of the chart is to provide students with the big picture. The right-hand panel provides additional detail about the seven major elements.

FIG. 13.3. Curriculum charts for Word Work: classroom and teacher versions.

The first and last elements in the chart, Reading/Writing Community and Projects, are curricular “bookends” that anchor the phonics curriculum within a purposeful context for early literacy development. These end points establish and confirm the goals and values of reading and writing at the beginning and end of the school year. The strategy foregoes skills instruction at the outset of the school year, waiting until students’ interest has been captured. Likewise, the end of the school year is given over to thematic projects, when skills developed earlier in the year are applied to large-scale student-centered activities.

The second element, Beginning Word Work, accomplishes three outcomes. First, students learn that a special time will be set aside most days to “work with words,” to learn to read and spell new words. Second, they are introduced to a vocabulary for talking about reading, writing, and language. Many students, even in the late primary grades, are unclear about ideas that skilled readers (including teachers) take for granted: sentences, stories, words, and so on. If students are to assume responsibility for their own learning, they must know how the language-print system works, and they need a vocabulary to talk about the system. Third, students learn how to work in small groups—dyads and triplets—to solve problems collaboratively. Very young children are seldom adept at cooperative learning; they are egocentric and unskilled at genuine collaboration.

The third element, Making Sounds, introduces the concept of phonemic awareness. Seven basic consonants are presented in this segment as sounds that can be produced or articulated in specific ways. This segment, although brief (a single 2-week lesson block), provides the essential link between letters and sounds during the rest of the curriculum.

The fourth element, Making Words/Short Vowels, introduces students to the construction of consonant-vowel-consonant sequences—words. Short vowels or “glue letters” come first for two reasons. First, the spelling pattern for short vowels is simpler than for long vowels. Second, students learn to distinguish between letter names and letter sounds (“The letter a makes the sound /a/”), with the vowel “names” coming later. The short vowels are introduced in order a, i, o, e/u, 2-week lesson blocks for each segment. The order reflects pragmatics; a is the first and often first learned letter of the alphabet, whereas / and o are “nice” letters, straight and round! E is problematic for various reasons, and so is combined with u for the final lesson block.

The fifth element, Making Words/Long Vowels, presents the Anglo-Saxon vowel-marking system for long pronunciations. This element also introduces the major suffixes: -ed, -s, -ing, -er, and -est. The sixth element, Big Words, presents the concept that long words are combinations of short words. In Anglo-Saxon, compounding is the basic morphological device for creating complex words, setting the stage for the root-affix patterns in the Romance layer of English.

These elements may resemble the objectives in other phonics programs. The difference is that Word Work elements are “big outcomes,” covering broad domains, whereas objectives tend to be smaller and more specific. In Making Words/Short Vowel a, for instance, the outcome is skill in decoding all CVC patterns in which short a is the vocalic center unit. A conservative estimate of the productivity of this principle suggests that students gain access to more than 2,000 CVC building blocks during this 2-week lesson unit. Focusing on larger goals means that learning is more efficient, more transferable, and more comprehensible.

Word Work is a cumulative curriculum. When moving from one element to the next, previous learning is connected to new concepts. After teaching short a, for instance, short / is introduced as a second glue letter along with short a, doubling the number of words in students’ repertoire.

The curriculum spirals from kindergarten through second grade. The same objectives are covered in each grade, at different rates and with different emphases, depending on students’ developmental levels and individual differences among students and classes.

There are major and minor elements in the curriculum. Major elements include those highly productive patterns essential for fluent reading and readable spellers. Minor elements are specialized patterns added along the way depending on teacher judgment. Critics of any systematic effort to teach letter-sound correspondences often point out irregularities in English orthography. The secondary strand of Word Work includes these minor elements, which students must eventually master, but which do not warrant large time investments. The minor elements occur frequently in printed material, ensuring that students in a print-rich environment have numerous occasions to “read” these patterns (e.g., -ight). What about conventional spellings? Parents who readily purchase “Brite Nite Lites” at the local hardware store may be unhappy when their children show them papers with such “invented” or “temporary” spellings, even though the children’s work shows extraordinary imagination and coherence. The goal of Word Work is that students quickly reach the point where they can write with facility and ease, and where their work is readable. The secondary strand then responds to parents’ and teachers’ concerns that students “get it right.”

Instructional Design

Both skills-based and whole language programs intermingle skills development with comprehension, and separate decoding and spelling. Word Work lessons reverse this strategy, commingling decoding and spelling as critical elements in reading and writing. The basic instructional strategy begins each instructional segment with a focused lesson that takes a thin “slice of time,” early in the morning when everyone is fresh, 3 or 4 days a week, dedicated to the study of “words.” Time allocation depends on the activity, but generally amounts to 12 to 35 minutes. Some lessons entail direct instruction of small groups; three groups for 10 minutes each takes 30 to 35 minutes, the upper limit. Whole-class or small-group activities take about 15 to 20 minutes. The idea is to focus on letter-sound correspondences for brief amounts of time, leaving most of the school day for text-level reading and writing.

Word Work sessions are organized into Lesson Blocks, 2-week segments allocated to a specific curriculum element. A block typically begins with teacher-led small-group instruction on a particular curriculum concept (e.g., short a words), and ends with teacher-led whole-class assessment. Between these “bookends,” the block allows a variety of options, including whole-class, small-group, and individual activities, and some teacher-led reinforcement and review lessons, but most lessons are student centered, the teacher’s role being to monitor and facilitate student work. Two weeks is a reasonable amount of time to cover an element, and the sustained emphasis over an extended time supports in-depth learning and application. An important feature of the Lesson Block design is the review at the beginning of the second week. Young children are distracted by weekends (even more by holidays), and the Lesson Block design bridges these interruptions to support cumulative learning.

Small-group problem-solving activities are a distinctive feature of Word Work. The aim is to lead students to become “junior cryptographers.” As noted earlier, the metaphonics principle assumes that students benefit from understanding English orthography as a system, and from “thinking” about the alphabetic principle and letter-sound relations. These accomplishments require reflective learning, and thus Vygotskian principles come into play. This strategy calls for students to interact with one another, a tough task for 5- and 6-year-olds. To support these activities, GroupTask cards support students in solving a problem and completing a task. The program also includes Kid Kards as options for classroom practice and take-home assignments. The aim is a balance between individual and group activities, between teacher-directed and student-centered tasks. Students can learn much from one another in group settings when these are genuinely collaborative. They also need to learn how to be responsible for individual work and take-home activities provide a way to link parents to school learning.

GroupTask activities are guided by several principles. First, the tasks are designed to pose “real” problems with open-ended possibilities. The point is not only to find the correct answer, but to justify the work. Task difficulty appears to be a critical factor. Once students have the idea of the basic CVC unit, building short words no longer poses a challenge. At this point, the teacher can assign words like sassafras or discombobulate.

A second principle is “not whether but when.” In primary classrooms with multiple activities, Word Work is sometimes included as a “center.” What if a student never chooses this center? The practical advice is that every student should cycle through every center during each week. If a student has not selected this option by Thursday morning, then he or she no longer has a choice.

A third principle is the importance of not teaching during GroupTask exercises. The teacher should spend this time monitoring and facilitating student interactions and activities, and assessing students’ skill and knowledge. Later in the school year, when the teacher has identified individuals who need additional help, GroupTask activities may allow an opportunity for specific instruction. In general, however, this is a time to observe and evaluate.

PRELIMINARY RESULTS

So much for theory and program design—is the concept effective? Word Work is still under development, but pilot evaluations have been conducted in three school sites as part of the developmental activities. Findings from these studies are sketched in this section.

Fruitvale Elementary

South of Stanford University, Fruitvale School serves a varied student population. Some students are from middle-class families fleeing the pressures of the San Francisco Bay Area and Silicon Valley; within reasonable driving distance of the big city, parents can raise their children in a rural setting complete with ponies and horses. Other children are refugees of a different sort, leaving poverty for affordable housing and a more protected situation. And there are still farm-worker families in the Salinas Valley. Fruitvale provided two primary reading programs: Spanish-bilingual and literature-based English. The Chapter I reading specialist was the contact person for Word Work; she had been involved in the early development of READ Plus, and was familiar with social-cognitive strategies for literacy instruction.

Fruitvale implemented literature-based reading in response to the 1987 California Language Arts framework (California Department of Education, 1987). Changing demographics and declining test scores led to concern about the reading program, and the reading specialist approached me in the fall of 1993 to discuss ways to strengthen the program. Discussions with the primary-grade teachers led to implementation of Word Work in January 1994 in several English classrooms: two first-grade classrooms, a first-second combination, and two second-grade classes. During the school year, project staff visited classrooms, consulting with teachers, observing program implementation, collecting samples of student reading and writing, and interviewing teachers and focus groups. Participating teachers were all familiar with literature-based methods. Some were more involved in Word Work than others, judging from classroom observation, and level of participation is noted in the evaluation design.

We collected several indicators of student achievement, including standardized test summaries (CAT-5). Word Work is not primarily aimed toward improved standardized test scores, but students with better decoding and spelling skills should do better on such instruments. The District’s Reading Fluency test was administered in the fall, winter, and spring. The measure is the number of words read per minute by each student from one or more passages varying in the number of words and readability level. Each passage is around 180 words in length. Because Word Work is designed to enhance decoding accuracy, reading speed is not necessarily the most appropriate measure, but if the program is effective, then students should become both faster and more accurate. They should also become more competent spellers, and thus we collected writing samples from those classrooms where teachers were willing to provide student work.

The Fruitvale evaluation focused on three questions:

• To what degree did average performance for students in the Word Work curriculum exceed that of students in the regular literature-based curriculum?

• To what degree did Word Work improve the reading performance of students whose achievement was low at the beginning of the school year?

• What was the effect of Word Work on students’ spelling and writing performance?

Evidence on the first question came from the standardized tests (Table 13.1). First- and second-grade performance of Fruitvale students was at or above the district average, although the school was the “poor” school in the region. First-grade performance was noticeably higher than average, and exceeded the performance of other schools by 10 to 20 normal curve equiva-lents. Because decoding skills are important in the early stages of reading acquisition, this pattern suggests a significant impact of Word Work during this critical period.

Standardized Language Arts Test Scores (CAT-5 Normal Curve Equivalents) for Fruitvale Students, Compared With District Averages

Additional comparisons come from analysis of within-school effects at Fruitvale on the reading fluency tests. Average effects can obscure fine-grained effects. Stanovich (1986) documented the “Matthew effect”; in any new program, more able students benefit the most. We assessed the Matthew effect by a scatterplot analysis of reading fluency gains for students at different entry levels. Figure 13.4 shows the results. The graphs display the winter-spring profile for each first-grade class. The heavy diagonal line is the constant-performance reference level; if a student read at the same rate during winter and spring testing, he or she would fall near this line. Any point above the line marks a student who gained in reading fluency from winter to spring. In both classes, most students read 40 words or fewer during the winter assessment; imagine a “fence” extending upward from the baseline at this point, and you can see that most students are left of the boundary. During the spring testing, students in the two classes differed greatly. Take the district average of 40 words per minute as a reference point, and imagine another fence that stretches horizontally at the 40-word level. Most students in the moderate-implementation class are below this fence, whereas most (80%) in the high-implementation class are above the fence. Moreover, the greatest gains in the high-implementation class were by students with low winter scores. Only three students “stayed in the cellar” in this class. The one student who performed substantially above average during the winter testing profited as well, scoring at the third-grade level by the end of first grade.

FIG. 13.4. Scatterplots of reading fluency performance in Fruitvale first-grade classrooms.

Phonics programs typically focus on oral reading fluency. A strong argument can be made for the importance of spelling as an indicator of students’ knowledge about patterns in the English spelling–sound system. Whole language advocates have argued that readers can rely on context to make sense of print. They are probably right; readers can sometimes guess the general meaning of a passage based on minimal cues. Writers face a more demanding task. Invented spelling, the effort of young students to mimic print, is an important stage in the development of literacy. But if students cannot read their compositions a week or two later, then the function of print has failed.

Student writing samples were limited in quantity and scope, but the data in Fig. 13.5 nonetheless convey an important message. The samples are from the high-implementation first-grade classroom. At Thanksgiving, students struggled to express themselves. By April and May, students composed texts of remarkable creativity and fidelity. The papers are lengthy, interesting, and readable. The literature-based environment encouraged students to write; Word Work provided the spelling skills to support this effort. Students could draw on “topical webs” for content words (clown), and “word lists” for commonplace spellings (when). They were on their own to “attack” other spellings (reddy and butty for ready and body). The teacher did allow editorial teams to advise one another about spelling and grammar. Although these papers employ both phonological and conventional spellings, they are of unusual quality for first graders.

FIG. 13.5. Fall and spring writing samples from the high-implementation classroom. Spring samples are from high- and low-achieving students.

In response to the 1987 California Language Arts Framework, Hickory Grove teachers implemented a literature-based program. Hickory Grove serves an upward-oriented middle-class neighborhood in the East Bay region of San Francisco. Most families are successful by dint of hard work. They want the best for their children, and they ask much of the schools. Although teachers concur with these aspirations, there are understandable tensions between developmental growth and surefire results, between basic skills and social–cognitive growth.

Teachers were generally pleased with student achievement, but some parents had expressed concern about phonics and spelling. The district curriculum coordinator learned about Word Work at a November conference, and in January 1995, first-grade teachers at Hickory Grove decided to explore the program. Their input played a vital role in refining sequence, materials, and activities. When should vowel digraphs be introduced? How much emphasis on conventional spellings? How to sustain student interest?

Throughout the school year, Word Work staff provided ongoing support through workshops and conferences with the Hickory Grove teachers. Two assessments were also conducted in December–January and May–June. The first assessment consisted of writing samples from all first graders, 154 students in six classrooms. Four classes were straight firsts, and two were K−l combinations. Matched pre–post scores were available for 140 students. Missing scores reflect mobility; students who left or entered mid-year did not differ discernibly from the final sample.

Students wrote to two prompts: “A special person” in the winter, and “My summer vacation” in the spring. Each sample was scored by two staff members on the three dimensions: spelling, length, and coherence. Teachers and staff developed the scales collaboratively during the fall of the school year. Both teachers and, to some degree, students knew the criteria. Students understood that these papers were “special,” but that they would not be graded on them. Writing was commonplace in the classrooms, and these papers were written under normal conditions. Students had as much time as they wished, and could call on the teacher for assistance. The papers were first drafts.

Forty-six students were also administered the Interactive Reading Assessment System (IRAS; Calfee & Calfee, 1981) in December–January and May–June. IRAS is an individualized multicomponent performance test covering decoding, spelling, vocabulary definition, oral reading, and passage comprehension (narrative and expository), along with metacognitive questions about each component. The data of most relevance here are spelling (15 synthetic words ranging from simple CVCs like dut to complex words like thr inker lant), meta-spelling (“How do you know how to spell ________?”, a 6-point scale from no response [1] to a well-formed explanation [6]), and sentence reading (ranging from 1.0 to 4.0 in readability). Each teacher identified six students spanning a range of achievement (upper, middle, lower), one boy and one girl at each level.

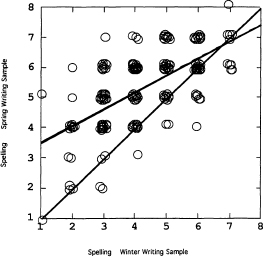

Writing data are shown in Table 13.2. The main questions in this evaluation center around student progress in the three dimensions. Hickory Grove children enter first grade ahead of the game; the district does not administer standardized tests in the early grades, but about a 1.5 grade-level equivalent. In the 6 months from December–January to May–June, the students moved almost 1.5 units on the 8-point spelling scale, a large and statistically significant shift. Figure 13.6 presents a scatterplot of the pre-post scores. A substantial number of students scored at Levels 2 and 3 on the spelling scale in winter, but virtually all performed at Level 4 or higher in spring. The students were also writing longer (almost a full page) and more coherent (centered around a single topic) essays. For first-grade teachers at Hickory Grove, the most significant outcomes of the writing program were students’ enthusiasm about writing, and the capacity to compose interesting, imaginative, and readable papers.

Table 13.3 presents the IRAS data. On spelling, students in December–January could handle simple synthetic words like dut, mape, and leb. In May–June, they spelled complex patterns like fening, sidded, and broint, more typical of second grade. In sentence reading, the 4.5 average means that students were able, on average, to read materials normed for the second half of second grade. In the 6 months, students had gained more than a full year on this scale.

Pre-Post Ratings [Mean, (SD)] of First-Grade Writing Samples, Hickory Grove Elementary School, December–January and May–June 1996

Note. N = 140.

FIG. 13.6. Scatterplot showing spelling scores for winter and spring writing samples, Hickory Grove Elementary School. Upper line is best-fit regression; lower line is no-growth indicator. Data have been jittered to show relative density at each point. N = 140.

Word Work emphasizes the metaphonic principle; understanding is as important as performance. First graders improved on the meta-spelling scale, but only slightly. One challenge is that very young students have trouble explaining anything. They are genuine novices, and tend to stay at a surface level when asked “Why?”

Hickory Grove first graders had a successful year. They entered ahead of the game, and finished with a solid mastery of decoding-spelling skills coupled with an enthusiasm for reading and writing. The children were as enthusiastic about skill learning as story reading and journal writing. Word Work time was alive with spirited activity, and flowed easily into the other parts of the school day.

Pre-Post Scores [Mean (SD)] of First-Grade Performance on Interactive Reading Assessment System (IRAS) in Spelling, Meta-Spelling, and Sentence Reading Subtests, Hickory Grove Elementary School, December–January and May–June 1996

Note. N = 140.

The third evaluation addresses the Matthew effect—how to help students in the lowest achievement levels. In spring 1996, the Reading Department of the Omaha Public Schools decided to investigate the potential of Word Work to assist kindergarten “graduates” judged at risk for first grade. Parents of 42 Chapter I students volunteered their children for a 6-week summer school.

First-grade entry is critical. Students who know their letter names, who possess phonemic awareness, who can read simple words and sentences have a clear and lasting advantage over their peers. Helping children who lack these skills to “catch up” is difficult. The purpose of this exploratory effort was to investigate the effectiveness of a concentrated literacy program that combined an explicit and separate decoding-spelling curriculum with comprehension and composition skills in a literature-based environment.

Four teachers conducted the summer program. They had limited familiarity with the program, but received ongoing support and supervision from the district reading coordinator. Class sizes were small, 7 to 12 students. Students spent most of the 3-hour school day reading (a variety of works) and writing (“letter” book, “story” book, and “animal” book). Each day included a Word Work segment, typically around 20 minutes, decoding-spelling concepts directly applicable to the “book work” that occupied the rest of the school day. This summary report presents two sets of data: a teacher checklist assessing letters and letter-sound relations, and a tile test (a performance assessment of letters, words, and sentences).

The district checklist showed that the students could recognize most letters when they entered the program (m = 20/26), but improved over the 6-week experience (m = 23/26). The five-letter tile test of letter names showed the same pattern, and was highly correlated with the teachers’ assessments of the complete alphabet. Most children had evidently learned their ABCs in kindergarten, and further refined their knowledge during the summer program. Teaching the ABCs does no harm, but does not guarantee literacy.

More significant for first-grade entry is awareness of letter-sound correspondences, the capacity to read simple words, and oral reading fluency. Students are more likely to succeed in first-grade reading if they can already read. Table 13.4 presents the findings for these outcomes. At the beginning of summer school, these postkindergarten graduates knew fewer than half of the letter-sound correspondences, could read only one or two of five simple words, and were completely stymied when confronted with a short sentence. Six weeks later, the majority knew 20 or more of these relations, and only

Test Scores [Mean and (SD)] for Teacher Ratings of Students’ Letter-Sound Knowledge and Performance on Tile Tests of Word Reading and Sentence Reading, Omaha Postkindergarten Summer Reading Program

Note. N = 42 for June and July tests; N= 29 for September tests.

one student knew fewer than half of the letter-sound correspondences. Figure 13.7 shows that progress was especially notable for those students with the lowest entry scores. Students also improved dramatically in word and sentence reading during this brief experience. More detailed analyses showed that boys and girls benefited equally, and that gains were present in all four classes. Finally, when the students were reassessed at the beginning of first grade, 6 weeks after the program ended, students had sustained most of the gains.

Observations and teacher interviews suggest that these dramatic improvements were achieved in a motivating, playful environment. The students were not force fed a diet of worksheets; instead, phonics was an active, hands-on activity, interesting in its own right, but also valuable because it allowed students to become adept at independent reading and writing. These findings point to the potential value of focused summer school experiences for at-risk students (Cooper, Nye, Charlton, Lindsay, & Greathouse, 1996).

FIG. 13.7. Scatterplot showing letter-sound pre–post data for Omaha summer school postkindergarten project. Teacher assessments of number of letter-sounds identified by each student at beginning and end of six-week summer school. Range from 0–26, N = 42.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS: WHAT TO DO?

The “great debate” has raged for decades, and today’s situation suggests that the extremes are far more popular than the middle ground. More troubling, the terms of the debate seem little affected by either research findings or practical experience. For instance, the recent California Reading Advisory (California Department of Education, 1996) “encourages” kindergarten teachers to work on phonemic awareness, and then places the task of “teaching reading” on the shoulders of first-grade teachers—a task to be completed by mid-year. Research shows that phonemic awareness is most effectively taught when combined with print awareness. My experience in the “down and dirty” of reading instruction suggests that, although the primary years are a critical time, all children are more likely to become fully competent if the entire primary team works toward this end.

This chapter has meant to convey a few central themes. First and foremost, all American students are capable of attaining high levels of critical literacy, even given today’s societal challenges: Continuing declines in family demographics, inadequate social services, and regular trashing of schools and teachers. If a child attends school with some regularity (and most do), we can promote both competence and enthusiasm for reading and writing.

This chapter has focused on print literacy. For students to learn decode and spell, a central requirement is a coherent, developmental curriculum grounded in the features of English orthography, and connected with purposeful activities. English spelling is a sensible and comprehensible match to the spoken language, but both students and teachers need clarity about the system. Today’s alternatives (learn on the fly or memorize a thousand objectives) don’t work.

A third theme centers around appropriate assessment, which taps into understanding as well as recognition, relying not on “cold turkey” oral reading but on “reading with meaning” passages that merit reading, and downplaying rote spelling tests in favor of accurate and fluent spelling in meaningful contexts.

The final theme emphasizes the teacher’s professional role in adapting curriculum and instruction to the needs of diverse students. The professional is knowledgeable about linguistics, child development, and sociocultural variations in language usage. For primary teachers, language and literacy are the most critical instructional domain, and teachers must resist pressures to spread themselves thinly across a broad spectrum foisted on them by policymakers.

The case studies sketched in this chapter show what is possible when first graders are immersed in a decoding-spelling curriculum based on orthographic principles, when instruction employs social–cognitive strategies, and when decoding-spelling is a distinctive curriculum strand directly coupled with purposeful reading and writing. They show how curriculum and instruction can provide the “engine” that produces genuinely powerful learning for all students.

REFERENCES

Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ashton-Warner, S. (1963). Teacher. New York: Simon & Schuster. Balmuth, M. (1982). The roots of phonics. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Bentin, S., & Leshem, H. (1993). On the interaction between phonological awareness and reading acquisition: It’s a two-way street. Annals of Dyslexia, 43, 125–148.

Brady, S. A., & Shankweiler, D. P. (Eds.). (1991). Phonological processes in literacy: A tribute to Isabelle Y. Liberman. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Calfee, R. C., & Calfee, K. H. (1981). Interactive reading assessment system (IRAS) (rev.). Unpublished manuscript, Stanford University.

Calfee, R. C., & Drum, P. A. (1986). Research on teaching reading. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 804–849). New York: Macmillan.

Calfee, R. C., & Henry, M. (1996). Strategy and skill in early reading acquisition. In J. Shimron (Ed.), Literacy and education: Essays in memory of Dina Feitelson (pp. 97–117). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton.

Calfee, R. C., & Patrick, C. P. (1995). Teach our children well. Stanford, CA: The Portable Stanford Book Series, Stanford Alumni Association.

California Department of Education. (1987). Language arts curriculum framework. Sacramento, CA: Author.

California Department of Education. (1996). Teaching reading: A balanced, comprehensive approach to teaching reading. Sacramento, CA: Author.

Chall, J. S. (1983). Stages of reading development. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Chall, J. S., Jacobs, V. A., & Baldwin, L. E. (1990). The reading crisis: Why poor children fall behind. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Cooper, H., Nye, B., Charlton, K., Lindsay, J., & Greathouse, S. (1996). The effects of summer vacation on achievement test scores: A narrative and meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research, 66, 227–268.

Elkonin, D. B. (1963). The psychology of mastering the elements of reading. In B. Simon & J. Simon (Eds.), Educational psychology in the U.S.S. R (pp. 165–179). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Lionni, L. (1994). Leo Lionni favorites: Six classic stories. New York: Knopf.

Mclntyre, E., & Pressley, M. (1996). Balanced whole language. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Share, D. L. (1995). Phonological recoding and self-teaching: Sine qua non of reading acquisition. Cognition, 55, 151–218.

Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 21, 360–406.

Venezky, R. L. (1970). The structure of English orthography. The Hague, Netherlands: Mouton.

Weaver, C. (1990). Understanding whole language: From principles to practice. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.