![]()

The Role of Analogies in the Development of Word Recognition

Usha Goswami

Behavioural Sciences Unit

Institute of Child Health

University College, London

Word recognition in beginning literacy poses a particular set of problems. The most important of these is how written words represent spoken words. Writing systems were invented to communicate the spoken language, and most writing systems do this systematically, by using an alphabet, a syllabary, or a set of logographs (characters, like $ or %) that convey meaning. Because English is an alphabetic language, children who are learning to read English must learn the systematic correspondences between alphabetic letters (or groups of letters) and sounds. This means that learning written language requires some understanding of spoken language. This is not surprising when one considers that writing systems are designed to convey speech.

In this chapter, we consider how the ability to reflect on spoken language might help a child to learn to read English. We investigate the most consistent level at which the English writing system (or orthography) represents sound (phonology), and examine whether English-speaking children use this level in reading acquisition. This entails the use of orthographic analogies in reading. We then contrast the strategies used by children learning to read English with those used by children learning to read other languages. Finally, we discuss the implications of the analogy research for classroom teaching.

ACQUIRING SPOKEN VERSUS WRITTEN LANGUAGE

Consider briefly the immense task that faces an infant who is beginning to acquire spoken language. The infant is faced with the problem of distinguishing units of meaning within an apparently seamless stream of speech. Although adults help to segment the speech stream by occasionally uttering words in isolation, exaggerating the pronunciation of key words, and so on, research has now established that infants are able to discriminate stimuli differing by a single phonetic segment within the first few months of life. For example, a 1-month-old infant can recognise when a p sound changes to a b sound (Eimas, Siqueland, Jusczyk, & Vigorito, 1971). In principle, this gives the infant the capacity to distinguish words from each other, because a phoneme is the smallest unit of sound that changes the meaning of a word. A word like bat is distinguishably different from pat, and tab is different from tap, because b differs from p. However, the ability to distinguish between these words is probably an emergent property of the development of speech perception (see Metsala & Walley, Chap. 4, this volume).

The task facing a young child who is learning to read seems somewhat easier. Although the child has to work out how units of meaning are represented by strings of letters, words in print are already segmented, because there are gaps between separate words on the page. Second, the target words are usually familiar—by the age of 5, children have acquired fairly extensive spoken vocabularies, and most early reading books take account of their reader’s language level. Third, at least at first glance, the phonemic units are already picked out for the child by the letters in each word, because alphabetic letters correspond to phonemes. Thus, it would seem that all that the child has to do to solve the problem of word recognition is to learn the correspondences between letters and phonemes. After all, if infants can recognize phonemic contrasts, surely it cannot be that difficult for children to segment spoken words into phonemes, to learn how the 26 alphabet letters represent these phonemes, and to blend the phonemes represented by these different letters into words?

The puzzle for psychologists has been that children, at least some children, do experience genuine difficulties with the task of learning to read. We now know that one source of these difficulties is a lack of phonological awareness. Although the ability to differentiate phonemes such as p and b is innate, the ability to become aware, or to consciously realise, that the p sound is different from the b sound is not innate. Whereas almost all children learn to comprehend and produce spoken language (even children who have severe educational difficulties), not all children find it easy to learn to read, even children who are doing very well at school in other respects. Individual differences in phonological awareness distinguish children who will become good readers from children who will become poor readers (e.g., Stanovich, Nathan, & Zolman, 1988). Poor phonological skills discriminate poor readers, whether the children with reading problems have general educational difficulties or not.

THE SPELLING SYSTEM OF ENGLISH

An additional problem, of course, is that the alphabet does not consistently represent the phonemes of spoken English. The spelling system of English was developed to keep the spelling of root meanings (morphemes) constant. For example, the root morpheme heal is used in the word health, leading to different pronunciations for the same spelling. There are also identical pronunciations for different spellings (e.g., heal–feel, light–site; see Katz & Feldman, 1981, 1983). This is very different from the spelling system used for a language like Serbo-Croatian. In Serbo-Croatian, the alphabet follows the principle “Spell a word like it sounds, and speak it the way it is spelled” (see Frost & Katz, 1992). If these principles were applied to written English, health would be pronounced “heelth,” and light would be spelled lite. The difference between English and Serbo-Croatian can be described as a difference in orthographic transparency. In Serbo-Croatian, each letter represents only one phoneme, and each phoneme is represented by only one letter, and thus the relationship between spelling and sound is transparent. English is orthographically nontransparent, because letters can represent more than one phoneme, and phonemes can be represented by more than one letter.

Many other Indo-European languages, such as German, Spanish, and Greek, are also orthographically transparent for reading (although not necessarily for spelling). These languages all have writing systems that demonstrate a high level of consistency in the correspondence between letters and phonemes. It is interesting to note that these countries do not have a debate about the best method of teaching initial reading. In fact, in Austria and Greece, the sequence in which the letters and their sounds are taught in school is decided by the government, and all schools follow the same teaching sequence. In Greece, they even use the same reading book. This lack of debate is probably a consequence of the high orthographic transparency of German and Greek. Because there is a 1:1 mapping between graphemes and phonemes, a phonics system of teaching initial reading is highly successful.

Although English does not have a 1:1 mapping between graphemes and phonemes, we can still calculate how many times a letter like a or b has the same pronunciation across different words. In a recent analysis of the statistical properties of the English orthography, Treiman, Mullennix, Bijeljac-Babic, and Richmond-Welty (1995) carried out such calculations for all of the consonant-vowel-consonant (CYC) words of English (vowels in this analysis included vowel digraphs like ai or ea, in which two letters represent one sound). Treiman et al. found that the pronunciation of the initial and final consonants was reasonably predictable. The first consonant (C1,) was pronounced the same in 96% of CVC words, and the final consonant (C2) was pronounced the same in 91% of CVC words. However, the pronunciation of vowels turned out to be very variable. Individual vowels were only pronounced the same in 51% of CVC words, and when Treiman et al. considered the initial consonant and the vowel as a unit (C1V), then only 52% of CVC words sharing a C1V spelling had a consistent pronunciation, even though initial consonants alone were so predictable. The greatest consistency of vowel pronunciation occurred when the vowel and final consonant were considered as a unit (VC2). Treiman et al. found that 77% of CVC words sharing a VC2 spelling had a consistent pronunciation. This analysis shows that the spelling system of English becomes more consistent when rhyming families of words are considered (heal–deal–meallhealth–wealth–stealth).

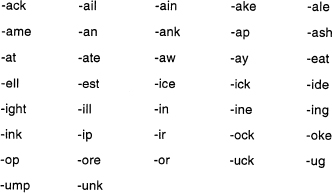

In fact, the number of different VC2 units in written English can be calculated as well. Stanback (1992) analyzed the different VC2 patterns in the 43,041 syllables making up the 17,602 words in the Carroll, Davis, and Richman (1971) word frequency norms for children. She found that the entire corpus was described by 824 VC2 units, 616 of which occurred in rhyme families. Wylie and Durrell (1970) pointed out that nearly 500 primary grade words were derived from a set of just 37 rimes (see Fig. 2.1). These analyses of the spelling system of English suggest that there are significant advantages in learning about VC2 units (i.e., spelling units that represent rhymes) during reading acquisition.

LEVELS OF PHONOLOGICAL AWARENESS

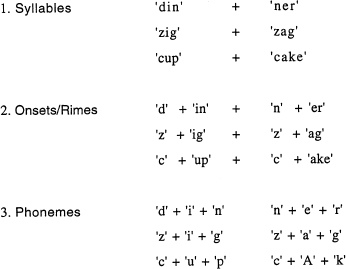

If the spelling patterns that correspond to rhymes are important for reading acquisition in English, then a sensitivity to rhyme may represent an important level of phonological awareness for children who are learning to read English. Although phonological awareness was initially measured at the level of the phoneme, we now know that phonological awareness can be measured at more than one level (see Fig. 2.2). Two other levels of phonological awareness have also been distinguished: syllabic awareness and onset-rime awareness.

FIG. 2.1. The 37 rimes in the Wylie and Durrell (1970) analysis of primary grade texts.

Phonemic awareness refers to the awareness that a word like cup consists of three phonemes, corresponding to the letters c, u, p. However, phonemic awareness appears to develop relatively late, and also develops partly as a consequence of learning to read and to spell (see Goswami & Bryant, 1990). Syllabic awareness and onset-rime awareness both appear to be present before a child begins to learn to read. Syllabic awareness is the ability to detect constituent syllables in words. For example, a word like popsicle has three syllables, whereas a word like dinner has two. Syllabic awareness appears to be present by at least age 4 (e.g., Liberman, Shankweiler, Fisher, & Carter, 1974). Onset-rime awareness is the ability to detect that a single syllable can have two units: the onset, which corresponds to any initial consonants in the syllable; and the rime, which corresponds to the vowel and to any following consonants (i.e., to VC2 units; see Treiman & Chafetz, 1987). For example, the onsets in health, stealth, and wealth are the sounds made by the letters h, st, and w, respectively. The rime is ealth. Whereas onsets are optional in English syllables, rimes are mandatory (words like eat and up have no onsets). Onset-rime awareness is also present by at least age 4 (Bradley & Bryant, 1983), and may even emerge as young as 2 or 3, via experience of nursery rhymes and such (Maclean, Bryant, & Bradley, 1987).

Onset-rime awareness and phonemic awareness are not completely distinct, however. Many English words have single-phoneme onsets; that is, they begin with a single consonant. As we have seen, the pronunciation of this initial consonant is highly predictable, being similar in 96% of English words. Similarly, some English words have single-phoneme rimes. A word like zoo or tree has a rime that consists of a single phoneme, albeit a vowel digraph. Thus, an awareness of onset-rime units within words necessarily entails a developing awareness of phonemes. Although studies have shown that onset-rime awareness precedes phonemic awareness in most English-speaking children (Kirtley, Bryant, Maclean, & Bradley, 1989; Treiman & Zukowski, 1991), this general conclusion refers to awareness of every constituent phoneme in words, rather than to awareness of particular phonemes such as the initial phoneme.

FIG. 2.2. Levels of phonological awareness.

PHONOLOGICAL AWARENESS AND LEARNING TO READ

A large number of studies have shown that phonological awareness measured at all three of these levels is important for reading development (e.g., Cunningham, 1990; Fox & Routh, 1975; Juel, 1988; Perfetti, Beck, Bell, & Hughes, 1987; Snowling, 1980; Stanovich, Cunningham, & Cramer, 1984; Stanovich, Cunningham, & Feeman, 1984; Tunmer & Nesdale, 1985; Vellutino & Scanlon, 1987; Wagner, 1988, Yopp, 1988; see also Stahl & Murray, chap. 3, this volume; Torgeson & Burgess, chap. 7, this volume). Some studies, however, have suggested a particularly strong connection between rhyme awareness and early reading (e.g., Bradley & Bryant, 1978, 1983; Ellis & Large, 1987; Holligan & Johnston, 1988). As we have seen, such a connection may be important because of the spelling system of English, which is highly consistent at the VC2 unit level. Words that share VC2 units usually rhyme (e.g., heal, meal, deal).

LEVELS OF PHONOLOGICAL AWARENESS AND LEARNING TO READ PARTICULAR ORTHOGRAPHIES

Phonological awareness has also been shown to be an important predictor of reading development in other orthographies, including highly transparent orthographies and orthographies like Chinese and Japanese (e.g., Caravolas & Bruck, 1993; Cossu, Shankweiler, Liberman, Tola, & Katz, 1988; Gom-bert, 1992; Huang & Hanley, 1995; Lundberg, Olofsson, & Wall, 1980; Mann, 1986; Naslund & Schneider, 1991; Porpodas, 1993; Schneider & Naslund, in press; Wimmer, Landerl, Linortner, & Hummer, 1991; Wimmer, Landerl, & Schneider, 1994). However, when studies of other languages have included a measure of rhyme awareness, they generally have failed to find a strong connection between rhyming and reading (although see Lundberg et al., 1980). For example, a study in German by Wimmer et al. (1994) found that rhyme awareness in German children was not connected to early reading development at all. Instead, rhyme only became an important predictor of reading later in development, when German children were acquiring automaticity. This pattern is the opposite of that found in studies in English, where the predictive strength of rhyme measures appears early, and may drop out by the age of 6 years (e.g., Stanovich, Cunningham, & Cramer, 1984). Thus, a particularly strong connection between rhyming and early reading does not appear to hold for orthographies other than English.

This raises the interesting possibility that the level of phonological awareness that is most predictive of reading development may vary with the orthography that is being learned. Different levels of phonological awareness may interact with the statistical properties of the orthography (its transparency), so that the spelling units that offer the most consistent mappings to phonology in a particular orthography become particularly salient to the phonologically aware learner. For children who are learning to read English, this means that rhyme awareness should be an important predictor of learning to read, and that the spelling sequences that reflect rimes—VC2 units—should have a special functional salience. For children who are learning to read more transparent orthographies, phonemic awareness may be a more important predictor of learning to read, and individual grapheme-phoneme correspondences may have a special salience.

ORTHOGRAPHIC ANALOGIES AND RIME UNITS IN ENGLISH

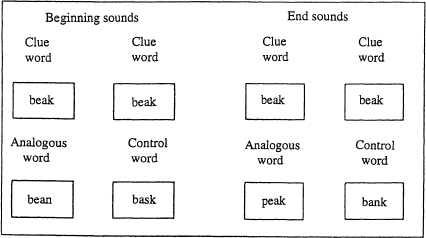

In fact, there is quite a lot of evidence that rimes are functionally important units for young readers of English. Most of this evidence comes from research into children’s use of orthographic analogies in reading. An orthographic analogy involves using a shared spelling sequence to make a prediction about a shared pronunciation. For example, a child who knows how to read a word like beak could use this word as a basis for reading other words with shared spelling segments, such as peak, weak, and speak, or bean, bead, and beat. Notice that in order to use a word like beak as a basis for reading a new word like peak, the child is making a prediction about the pronunciation of the new word that is based on the shared rime. In order to use beak as a basis for reading bean, however, the child is making a prediction about the pronunciation of a spelling unit that crosses the onset-rime boundary. The shared spelling sequence bea- in beak and bean corresponds to the onset and part of the rime (C1V).

When children’s ability to use a word like beak as a basis for reading analogous words like peak and bean is assessed experimentally, it turns out that rime analogies are easier than analogies based on the onset and part of the rime. Rime analogies also emerge first developmentally, appearing in children’s spontaneous reading behavior before onset analogies or analogies based on the onset and part of the rime. For example, in some of my first analogy experiments, I asked 5-, 6-, and 7-year-old children to play a clue game about working out words (Goswami, 1986, 1988; see Fig. 2.3). In this game, the children learned to read clue words such as beak, and were then asked to read new words like peak and bean, using their clue to help them. The children were pretested on the latter words prior to learning the clue words, to make sure that they really were new to the children, and the clue words remained visible during the testing phase, to make sure that the children did not forget them. The results showed that words like peak were easier to read by analogy to the clue word than were words like bean. This finding was particularly marked for the younger children.

In subsequent work, I have shown that analogies based on rimes are typically the only analogies made by very young readers (Goswami, 1993). Once a child has been reading for a period of around 6 to 8 months, then other analogies are also observed, such as analogies between the onset and part of the rime (beak–bean), analogies between shared vowel digraphs (beak–heap), and analogies between onsets (trip–trim). Analogies between onsets have only been studied using consonant clusters (Goswami, 1991). In a clue word study in which children learned clue words like trip as a basis for decoding new words like trim (shares initial consonant cluster), and clue words like desk as a basis for decoding new words like risk (shares final consonant cluster), I found that analogies were restricted to the shared consonant clusters that corresponded to onsets. The children made a significant number of analogies between clue words like trim and test words like trot. They did not use analogies between clue words like desk and test words like risk, even though these words also shared consonant clusters with the clue words. Thus, for consonant clusters, the phonological (onset-rime) status of the shared spelling sequence appears to have a clear effect on children’s analogies.

FIG. 2.3. The clue word task.

Such analogies are not simply an artifact of the clue word technique of showing children words in isolation, because they are also observed when children are reading stories rather than playing the clue game (Goswami, 1988, 1990a). If a clue word is embedded in the title of a story, and analogous words appear in the story text, then children who learn the clue word as part of the title read more of the analogous words in the story correctly than do children who do not learn the clue word as part of the title. This analogy effect operates in addition to the effects of story context. The context of the story helps the children in both experimental groups to read the analogous words in the text correctly, but the children who learn the clue word via the story title have a significant extra advantage. Finally, orthographic analogies really do depend on shared spelling patterns, and are not the result of a simple form of rhyme priming. If children are taught to read a clue word like head, which is analogous in spelling to a rhyming word like bread but not analogous in spelling to a rhyming word like said, then most analogies are restricted to the rhyming words with shared spelling patterns (Goswami, 1990a).

The orthographic analogy evidence that rimes are functionally important units for young readers of English has now received support from a number of studies using converging methods (e.g., Bowey & Hanson, 1994; Bruck & Treiman, 1992; Ehri & Robbins, 1992; Goswami, 1986, 1988, 1991; Muter, Snowling, & Taylor, 1994; Treiman, Goswami, & Bruck, 1990; Wise, Olson, & Treiman, 1990). However, there is one important link that remains to be discussed, and that is the link between analogies and phonological skills. From the research discussed so far, we know (a) that rhyme awareness is an important predictor of reading development in English, (b) that young children use rimes in their reading, and (c) that the rime is the level at which the English orthography has the greatest consistency (VC2 units). A connection between these three facts remains to be established experimentally. For example, (a) and (b) may be related because children with better rhyming skills use more rime analogies. Similarly, (b) and (c) may be related because rimes are useful units for learning to read English. Finally, (a), (b), and (c) may all be related. Phonological skills predict reading development in all orthographies, but the special connection between rhyming and reading in English may be a direct result of the statistical properties of the English orthography, which makes rime units particularly useful for word recognition in English.

EVIDENCE FOR A CONNECTION BETWEEN (a) AND (b): RHYME AWARENESS AND RIME ANALOGIES IN ENGLISH

As noted previously, (a) and (b) may be related because children with better rhyming skills use more rime analogies. There is some evidence that this is the case, at least when rhyming and analogy use are measured in children of the same age (Goswami, 1990b; Goswami & Mead, 1992). In our studies, we examined whether children’s performance in the clue word analogy task was more strongly related to their performance in some phonological awareness tasks than others. For example, in Goswami (1990b), I gave 6- and 7-year-old children the Bradley and Bryant oddity task, which measures onset-rime awareness, and a phoneme deletion task developed by Content, Morais, Alegria, and Bertelson (1982). In the first task, children have to detect the odd word out in sets of words like fan, cat, hat, mat; and in the second children are asked to delete either the first (beak–eak) or the last (beak—bea) phoneme in spoken words.

The results showed that there was a specific connection between onset-rime knowledge and rime analogies. Onset-rime skills were related to analogizing even after controlling for vocabulary skills and phoneme skills, whereas phoneme deletion did not retain a significant relationship with analogising after controlling for vocabulary skills and onset-rime knowledge. In a related study by Goswami and Mead (1992), we included more phonological measures, such as syllable and phoneme segmentation, and we included a test of nonsense word reading (vep, hig) as well. We then looked at the relationship between the different phonological variables and analogy use after controlling either for reading age alone, or for both reading age and nonsense word reading. Each set of equations produced a consistent set of results. If reading age was controlled, then the onset-rime measures retained a significant relationship with rime analogies (these measures were the rhyme oddity task and onset deletion), but the phonemic measures did not (these measures were final consonant deletion and phoneme segmentation). In contrast, both the phonemic and the onset-rime measures retained significant relationships with onset-and-part-of-the-rime (beak-bean) analogies. When reading age and nonsense word reading were controlled, then the only variables to retain a significant relationship with rime analogies were the oddity rhyme measures. The only variables to retain a significant relationship with onset-and-part-of-the-rime analogies were the consonant deletion measures. Because onset-and-part-of-the-rime analogies require segmentation of the rime, this is not really surprising. Knowledge about rhyme seems to have a strong and specific connection to children’s use of rime analogies, whereas analogies between spelling sequences corresponding to the onset-and-part-of-the-rime are related to more fine-grained phonological knowledge about phonemes.

EVIDENCE FOR A CONNECTION BETWEEN (b) AND (c): ANALOGIES IN OTHER ORTHOGRAPHIES

As noted earlier, young English-speaking children may use rime analogies in their reading because the rime is the level at which the English orthography has the greatest consistency. One way to examine this connection, which is the connection between facts (b) and (c) discussed earlier, is to study children’s use of analogies in orthographies other than English. It is important to note that analogy is not necessarily a strategy that young children apply consciously, although we can certainly teach children to use analogies (see later discussion). Rather, in my research analogy is conceived of as an automatic process, driven by the level of a child’s phonological knowledge and by the nature of the orthographic-phonological relations that operate in a particular orthography (see also Goswami, in press; Goswami, Gombert, & Fraca de Barrera, in press). From this perspective, analogies should operate in every writing system. However, analogies in a very transparent orthography would reflect grapheme–phoneme relations, and analogies in English would reflect rime-based coding.

One way of comparing the salience of rime units in languages other than English is to study nonsense word reading. Matched nonsense words can be derived that either have rimes that are familiar from real words, as in the English example dake (cake, make), or unfamiliar (daik). The rime spelling pattern -aik does not occur in any real words in English. This means that although children can read a nonsense word like dake by using a rime analogy or by assembling its constituent grapheme–phoneme correspondences, they can only read a matched nonsense word like daik by assembling its constituent grapheme–phoneme correspondences.1

Similar sets of nonsense words can be derived for other languages. The importance of rime units in reading these different orthographies can then be assessed by the magnitude of the difference in reading accuracy and reading speed between nonsense words with familiar rimes (e.g., dake) compared to nonsense words with unfamiliar rimes (e.g., daik) in each orthography. This difference for English, French, and Greek2 is shown in Fig. 2.4 (see Goswami, Gombert, & Fraca de Barrera, in press; Goswami, Porpodas, & Wheelwright, 1997, for more detailed information about these experiments). Greek is highly transparent, French is less transparent than Greek but more transparent than English, and English is the least transparent of the three languages. As the figure shows, the rime familiarity effect varies with orthographic transparency. The largest effect was found in English, a smaller effect was found in French, and there was no effect of orthographic familiarity at the level of the rhyme at all for the Greek children.

FIG. 2.4. The rime/rhyme familiarity effect in English, French, and Greek.

In fact, these cross-linguistic studies also showed that spelling patterns for rhymes in bisyllabic and trisyllabic words were very salient to children who were learning to read English. If a nonsense word shared a rhyme spelling pattern with a real word (e.g., bomic–comic, taffodil–daffodil), then it was easier to read than a nonsense word that did not (e.g., bommick, tafoddyl). Again, this difference was not found for the other languages studied. This raises the intriguing possibility that the importance of rhyme awareness for predicting reading development in English is picking up a level of analysis that goes beyond monosyllabic words. Rhymes and rimes are not necessarily the same units when words of more than one syllable are considered. For example, behind and unwind share the rime of the second syllable and also rhyme, whereas wagon and melon share the rime of the second syllable but do not rhyme (examples from Brady, Fowler, & Gipstein, in preparation). In some phonological awareness tasks using multi-syllabic words, Brady et al. found that rhyme awareness precedes rime awareness in 4- and 5-year-old children. Thus, the spelling sequences that reflect rhymes in words of more than one syllable (e.g., agon in wagon) may be more important than individual rimes. It should be noted that future research may prove the rime perspective to be a limited one, with rhyme rather than rime being a more important variable in explaining reading development in English.

THEORETICAL REASONS FOR PROPOSING A CONNECTION BETWEEN (a), (b), AND (c): INTERACTIVE THEORIES OF READING DEVELOPMENT

I turn finally to the possibility that all of the evidence for facts (a), (b), and (c) discussed previously is related, namely to the possibility that the special connection between rhyming and reading in English is a direct result of the statistical properties of the English orthography, which make rime units particularly useful for word recognition in English, and thus lead to rimes being functional units in beginning reading. Although there is little direct evidence for this possibility at the moment, it is consistent with a number of recent theories of reading development that have proposed that children’s phonological knowledge plays a role in the development of their orthographic representations (e.g., Ehri, 1992; Goswami, 1993; Hatcher, Hulme, & Ellis, 1994; Perfetti, 1992; Stuart & Coltheart, 1988). Although only some of these theories focus on rimes, the general spirit of interactive theories is consistent with the special connection between rhyming and reading discussed previously. Traditional stage models of reading, such as those proposed by Frith (1985), and by Marsh, Friedman, Welch, and Desberg (1980), are not consistent with this special connection.

In traditional stage models of learning to read (Frith, 1985; Marsh et al., 1981), children are thought to begin to learn to read by using holistic strategies (the logographic stage), to progress to using letter–sound correspondences (the alphabetic stage), and to finally become able to use orthographic strategies that involve larger spelling units. This stage sequence has been taken to be invariant across orthographies, a view that may prove misguided (e.g., Porpodas, 1995; Wimmer, 1993). According to stage models, the approach that children take to the task of learning to read is qualitatively different at different stages of the reading process, although earlier strategies remain available as the later stages are attained.

In contrast, the newer interactive models of learning to read conceptualize reading as an interactive developmental process from the very earliest phases. These new theories propose that children’s orthographic knowledge is founded in their phonological skills. In other words, the phonological knowledge that children bring with them to reading plays an important role in establishing orthographic recognition units from the earliest phases of development. During the developmental process, phonological and orthographic knowledge continuously interact in increasingly refined ways. A child’s phonological knowledge will partly determine that child’s learning about the orthography, and that orthographic learning will in turn change the level of the child’s phonological knowledge. Because phonological knowledge can be measured at more than one level, it is possible that different levels of phonological awareness will interact with the statistical properties of the orthography that is being learned. Variations in the statistical properties of different orthographies mean that children who are learning to read in different orthographies may at first develop different orthographic representations (Goswami, Gombert, & Fraca de Barrera, in press; Goswami, Porpodas, & Wheelwright, 1997). The spelling units that offer the most consistent mappings to phonology in a particular orthography will be most salient to the phonologically aware learner.

For children learning to read English, these should be spelling units that correspond to rimes (Goswami, 1993). These are the VC2 units that Treiman et al. (1995) showed will provide the most consistent mappings from orthography to phonology as far as vowel pronunciations are concerned. We know that most children have good rhyming skills when they enter school, and thus this knowledge about rhyme should lead them to identify spelling units for rimes (see Goswami & Bryant, 1990). The development of orthographic recognition units that code rimes will in turn offer significant advantages in terms of pronunciation consistency over orthographic recognition units that code separate vowels and the C1V. Thus, children who are learning to read English may develop orthographic representations that accord a special status to rime units, whereas children who are learning to read more transparent orthographies may not. Notice that initial and final consonants (C1, and C2) may also benefit from this interactive process, because according to Treiman et al.’s statistical analysis these English spelling units also have highly consistent links to sound (see Ehri, chap. 1, this volume). Eventually, the interactive nature of the relationship between orthographic and phonological knowledge will help children to learn about all the constituent phonemes in words. Learning to spell will also significantly enhance this process (see Treiman, chap. 12, this volume).

ORTHOGRAPHIC ANALOGIES AND CLASSROOM PRACTICE

Let us summarize the position that we have reached so far. I discussed evidence that the most consistent links between the English spelling system and the sounds of spoken language occur at the level of the rime, that onset-rime awareness develops early in children, that there is a special link between rhyme (onset-rime) awareness and early reading in English, that children use rime analogies when they are reading, that children with better onset-rime skills make more rime analogies, that rime units have a special status for children who are learning to read in English, and that the special Status of rime units does not hold for more transparent orthographies. I then proposed that one way of integrating all of these findings was to think of reading development as a process of increasing interaction between phonological and orthographic knowledge. Although the level of phonological knowledge that is important for initial reading may vary with the orthography that is being learned, it was proposed that, for children who are learning to read English, links between phonology and orthography at the level of the rime may be particularly important.

If this is true, then we can predict that teaching children about rime analogies during initial reading instruction should be highly beneficial to their reading progress. There is some evidence that this is the case, although findings have been mixed (Bruck & Treiman, 1992; Ehri & Robbins, 1992; Peterson & Haines, 1992; Walton, 1995; White & Cunningham, 1990; Wise, Olson, & Treiman, 1990). So far, however, the interpretation of most of these studies has been limited by the use of fairly short training sessions, rather few analogy examples, and the occasional lack of adequate control groups. Nevertheless, I discuss two of the longer training studies in some depth, to illustrate the potential importance of including some instruction about rime analogies in a program of initial reading instruction.

In a study conducted in Canada, Peterson and Haines (1992) provided instruction in reading by rime analogy to a kindergarten group of 5- to 6-year-olds. A second group of children from the same classes acted as unseen controls. The experimental group was taught using a rime training method based on word families. Ten rime families were used during a training period of one month. Each child was given individual training with each family, in sessions lasting approximately 15 minutes each. In a given session, one word from the family being studied would be introduced (e.g., ball), and segmented into its onset and rime (b-all). A new word from the family was then added, also segmented into its onset and rime (e.g., f-all). The rime similarity was pointed out to the child and emphasized, and four more analogous words were gradually added in the same fashion (e.g., mall, wall, hall, gall). This word family approach, which entails the inclusion of more than one example of a rime-analogous word, may be important for learning. Research in problem solving by analogy has found that the provision of multiple example analogies significantly benefits learning (e.g., Brown & Kane, 1988; Goswami, 1992).

Peterson and Haines (1992) then assessed the effects of their rime analogy training by giving the children a posttest that involved reading new words by analogy to new clue words. This analogy test was also given to the control children from the same classrooms. The two groups of children had shown equivalent performance in this test prior to training, but at posttest the rime-trained group significantly outperformed the control group. The importance of an interactive relationship between phonology and orthography was also shown in this study. Peterson and Haines found that the children with better phonological segmentation skills benefited most from the analogy training, and that rime analogy training in turn benefited the development of segmentation skills. Similar findings have been reported by Ehri and Robbins (1992), who found that children who were good segmenters benefited more from rime analogy training than did children who were poor segmenters. However, the latter study used an artificial orthography.

Another positive result for rime analogy training was reported by White and Cunningham (1990), who also used a word family approach to analogy training. However, in contrast to Peterson and Haines, they included phonological training in their study as well. The children who took part were 290 6- and 7-year-olds in a particular school district in Hawaii. A group of teachers were trained to use an analogy reading program based on onsets and rimes, and the progress of the children in their classrooms was compared to that of a group of control children from comparable schools in the same district whose teachers had not received this analogy training.

The training period lasted for an entire year. The first 4 months were spent in phonological training, and the next 8 months were spent in linking phonology and orthography via analogy. The rime analogy training was based on learning 200 clue words and their rime families. The 200 key words were chosen to reflect major spelling patterns, in order to enable analogies to many other words (e.g., look–book, took, cook; nine–pine, mine, fine). As each key word was learned, it was written up on a “word wall” in the classroom (see Gaskins, chap. 9, this volume). For example, the children might learn about the nine family by being presented with a new word from one family, such as spine. They would have to decide to which family this new word belonged, and how to pronounce it. Similar instruction was then given in spelling.

At the end of the school year, the children in the analogy classrooms were significantly ahead of the children in the control classrooms in standardized measures of both decoding and reading comprehension. White and Cunningham reported similar results in a follow-up study conducted a year later, which involved an equally large group of children. As well as supporting the importance of including instruction about rime analogies in any program of reading instruction, the successful outcome of this study also provides support for the interactive models of reading development outlined previously. White and Cunningham’s program placed explicit emphasis on linking orthographic and phonological information at the level of the rime, and this interactive approach may have been an important component of its success. Similar results concerning the linkage of orthographic and phonological information (using plastic letters) have been reported by Bradley and Bryant (1983), and by Hatcher, Hulme, and Ellis (1994).

INTEGRATING ORTHOGRAPHIC ANALOGIES INTO YOUR CLASSROOM

The research discussed here has shown that there are three important points to bear in mind when introducing rime analogies into your own classroom. These are: provide phonological instruction about rhymes, provide orthographic instruction about rimes, and make the links between the two very explicit.

Providing Phonological Instruction About Rhymes

Phonological instruction about rhyme can be introduced in multiple ways. One of the most obvious ways is to use nursery rhymes. The goal of this instruction is to increase children’s awareness of the rhyming words. For example, this can be done by: (a) changing some of the rhyming words and asking the children to correct you (“Humpty Dumpty had a great fright!”); (b) making up variations on nursery rhymes (“Humpty Dumpty sat on a chair! Humpty Dumpty went to the fair!”); or (c) getting the children to be rhyme detectives, and to check whether matching words in nursery rhymes really do rhyme. A surprising number do not: For example Jack and Jill rhymes water with after, and Baa Baa Black Sheep rhymes dame with lane. Helping the children to sort out the real rhymes will provide valuable experience in learning about rhyme.

Providing Orthographic Instruction About Rimes

The best way to introduce orthographic instruction about rimes is to use rhyming families of words. The easiest way to teach children to use rime analogies is to make up a clue game of your own, based on these different rhyming families. To do this, you simply choose the spelling pattern or clue word that you want to teach, and then use it as a basis for analogies. For example, you could use a clue word from a favorite class story.3

• Begin by drawing the children’s attention to the rhyme family that you are using. For example, read them the story that uses the clue word, asking them to spot all the rhymes for the clue word as you read. You could then reread the story, pausing at the rhymes, so that the children have to supply them.

• Next, spell the clue word for the children, using a concrete material such as plastic letters or fuzzy felt letters stuck onto a board (you need letters that you can move around). Make a gap between the onset and the rime.

• Now make another word from the same family, also with plastic letters. Put it on the board underneath the clue word, and align the onset and rime in both words.

• Ask the children to read the new word for you, using the rime from their clue word, and working out the onset from their letter knowledge or from an alphabet frieze.

• Alternatively, you can ask the children to nominate rhyming words to spell, and help them to use the clue word to spell them.

Linking Phonological and Orthographic Instruction

The best way to link the phonological instruction with the orthographic instruction is to model the process of making the analogy for the children, using guided response questions. The kind of guided response questions that you use might be as follows (using the example clue word cap):

How can we use our clue to read this word? What is our clue word? Yes, it’s cap. What are the letters in cap? Yes, c, a, p. And what are the letters in this new word? Yes, t, a, p. So which bit of the new word can our clue help us with? Which part of the words are the same? That’s right, the a, p part. What sound do the letters a, p make in cap? Yes, ap. So what sound do they make here? Yes, it must be ap. So now we just need the sound for the beginning letter, which is—yes, t. What is the sound for t? We can check on the alphabet frieze. Yes, t makes a “t” sound, like in teddy. So our word is?—yes, t-ap, tap. So we can use cap to figure out tap, because they rhyme.

To use analogies in spelling, you simply reverse this procedure (“So if tap rhymes with cap, how do we know what letters to use to write the end part?” etc.). To use analogies for multisyllabic words, you divide each syllable into onsets and rimes, and so on. The goal of the clue game is to teach children to use analogies spontaneously in their own reading and spelling. As they practice making rime analogies, the children can learn that the English spelling system is not as capricious as it may seem.

SUMMARY

At the beginning of this chapter, I set out to examine the problem of how written words represent spoken words. We have seen that although English is an alphabetic language that uses individual letters to represent individual phonemes, the nontransparent nature of the English orthography means that the most consistent links between spelling and sound occur at the level of the rime (VC2 units). Rimes are usually groups of phonemes, corresponding to vowels and final consonants, and the final consonant helps to determine the pronunciation of the vowel.

We have also seen that there is a special relationship between rhyme awareness and reading development in English, a relationship that may not hold for more transparent orthographies. This suggests that phonological awareness at the level of the rhyme may be particularly important for learning to read English, because of the consistency of spelling units for rimes (VC2 units). Theoretically, this relationship can be modeled in terms of the interactions between phonological and orthographic knowledge that are important for reading development. Phonological knowledge at the level of the rhyme helps children to become aware of rime units in word spellings, and this orthographic insight in turn helps to develop phonemic knowledge of all the constituent phonemes in a word.

Finally, we have seen that the way to implement the spirit of interactive models of reading development in the classroom is to teach children explicitly about the relationships between spelling patterns and sound patterns. One way to achieve this is to teach children to use rime analogies. This instruction will encompass phonology (rhymes), orthography (rimes), and the connection between the two (analogies). Of course, it is important to note that there is more to learning to read than the use of rime analogies. As the other chapters in this book make clear, literacy processes in the home, instruction at other phonological levels, print exposure, and many other factors also play an important role in beginning literacy. However, rime analogies are an important part of achieving word recognition in English, and some instruction about rime analogies is easy to incorporate into any classroom program for the teaching of reading.

REFERENCES

Bowey, J. A., & Hansen, J. (1994). The development of orthographic rimes as units of word recognition. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 58, 465–488.

Bradley, L. & Bryant, P. E. (1978). Difficulties in auditory organisation as a possible cause of reading backwardness. Nature, 271, 746–747.

Bradley, L. & Bryant, P. E. (1983). Categorising sounds and learning to read: A causal connection. Nature, 310, 419–421.

Brady, S., Fowler, A., & Gipstein, M. (in preparation). Questioning the role of syllables and rimes in early phonological awareness. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Brown, A. L., & Kane, M. J. (1988). Preschool children can learn to transfer: Learning to learn and learning by example. Cognitive Psychology, 20, 493–523.

Bruck, M., & Treiman, R. (1992). Learning to pronounce words: the limitations of analogies.Reading Research Quarterly, 27(4), 374–389.

Caravolas, M., & Bruck, M. (1993). The effect of oral and written language input on children’s phonological awareness: A cross-linguistic study. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 55, 1–30.

Carroll, J. B., Davies, P. & Richman, B. (1971). Word frequency book. New York: American Heritage Publishing Company.

Content, A., Morais, J., Alegria, J., & Bertelson, P. (1982). Accelerating the development of phonetic segmentation skills in kindergarteners. Cahiers de Psychologie Cognitive, 2, 259–269.

Cossu, G., Shankweiler, D., Liberman, I. Y., Katz, L., & Tola, G. (1988). Awareness of phonological segments and reading ability in Italian children. Applied Psycholinguistics, 9, 1–16.

Cunningham, A. E. (1990). Implicit vs. explicit instruction in phonemic awareness. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 50, 429–44.

Cunningham, P. M. (1992). Phonics they use: Words for reading and writing (2nd ed.). New York: HarperCollins.

Ehri, L. C. (1992). Reconceptualizing sight word reading. In P. B. Gough, L. C. Ehri, & R. Treiman (Eds.), Reading acquisition (pp. 107–143). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ehri, L. C., & Robbins, C. (1992). Beginners need some decoding skill to read words by analogy. Reading Research Quarterly, 27(1), 12–28.

Eimas, P. D., Siqueland, E. R., Jusczyk, P., & Vigorito, J. (1971). Speech perception in infants. Science, 171, 303–306.

Ellis, N. C., & Large, B. (1987). The development of reading: As you seek, so shall ye find. British Journal of Psychology, 78, 1–28.

Fox, B., & Routh, D. K. (1975). Analysing spoken language into words, syllables and phonemes: A developmental study. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 4, 331–342.

Frith, U. (1985). Beneath the surface of developmental dyslexia. In K. Patterson, M. Coltheart, & J. Marshall (Eds.) Surface dyslexia (pp. 301–330). Cambridge, UK: Academic.

Gombert, J. E. (1992). Metalinguistic development. Hemel Hempstead, England: Harvester-Wheatsheaf.

Goswami, U. (1986). Children’s use of analogy in learning to read: A developmental study. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 42, 73–83.

Goswami, U. (1988). Orthographic analogies and reading development. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 40A, 239–268.

Goswami, U. (1990a). Phonological priming and orthographic analogies in reading. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 49, 323–340.

Goswami, U. (1990b). A special link between rhyming skills and the use of orthographic analogies by beginning readers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 31, 301–311.

Goswami, U. (1991). Learning about spelling sequences: The role of onsets and rimes in analogies in reading. Child Development, 62, 1110–1123.

Goswami, U. (1992). Analogical reasoning in children. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Goswami, U. (1993). Toward an interactive analogy model of reading development: Decoding vowel graphemes in beginning reading. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 56, 443–475.

Goswami, U. (Ed.). (1996). The Oxford reading tree rhyme and analogy programme. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Goswami, U. (in press). Integrating orthographic and phonological knowledge as reading develops: Onsets, rimes and analogies in children’s reading. In R. Klein & P. McMullen (Eds.), Converging methods for understanding reading and dyslexia (pp.).

Goswami, U., & Bryant, P. E. (1990). Phonological skills and learning to read. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Goswami, U., Gombert, J., & De Barrera, F. (in press). Children’s orthographic representations and linguistic transparency: Nonsense word reading in English, French and Spanish. Applied Psycholinguistics.

Goswami, U., & Mead, F. (1992). Onset and rime awareness and analogies in reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 27(2), 152–162.

Goswami, U., Porpodas, C., & Wheelwright, S. (1997). Children’s orthographic representations in English and Greek. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 12(3), 273–292.

Hatcher, P. J., Hulme, C., & Ellis, A. W. (1994). Ameliorating early reading failure by integrating the teaching of reading and phonological skills: The phonological linkage hypothesis. Child Development, 65, 41–57.

Holligan, C., & Johnston, R. S. (1988). The use of phonological information by good and poor readers in memory and reading tasks. Memory and Cognition, 16, 522–532.

Huang, H. S., & Hanley, R. J. (1995). Phonological awareness and visual skills in learning to read Chinese and English. Cognition, 54, 73–98.

Juel, C. (1988). Learning to read and write: A longitudinal study of 54 children from first through fourth grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 431–441.

Katz, L., & Feldman, L. B. (1981). Linguistic coding in word recognition: Comparisons between a deep and a shallow orthography. In A. M. Lesgold & C. A. Perfetti (Eds.), Interactive processes in reading (pp. 157–166). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Katz, L., & Feldman, L. B. (1983). Relation between pronunciation and recognition of printed words in deep and shallow orthographies. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 9, 157–166.

Katz, L., & Frost, R. (1982). Orthography, phonology, morphology and meaning. Holland: Elsevier Science.

Kirtley, C., Bryant, P., Maclean, M., & Bradley, L. (1989). Rhyme, rime and the onset of reading. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 48, 224–245.

Liberman, I. Y., Shankweiler, D., Fischer, F. W., & Carter, B. (1974). Explicit syllable and phoneme segmentation in the young child. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 18, 201–212.

Lundberg, I., Olofsson, A., & Wall, S. (1980). Reading and spelling skills in the first school years predicted from phonemic awareness skills in kindergarten. Scandanavian Journal of Psychology, 21, 159–173.

Maclean, M., Bryant, P. E., & Bradley, L. (1987). Rhymes, nursery rhymes and reading in early childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 33, 255–282.

Mann, V. A. (1986). Phonological awareness: The role of early reading experience. Cognition, 24, 65–92.

Marsh, G., Friedman, M. P., Welch, V., & Desberg, P. (1980). The development of strategies in spelling. In U. Frith (Ed.), Cognitive processes in spelling (pp. 339–353). London: Academic.

Muter, V., Snowling, M., & Taylor, S. (1994). Orthographic analogies and phonological awareness: Their role and significance in early reading development. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 35, 293–310.

Naslund, J. C., & Schneider, W. (1991). Longitudinal effects of verbal ability, memory capacity and phonological awareness on reading performance. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 6(4), 375–392.

Perfetti, C. (1992). The representation problem in reading acquisition. In P. B. Gough, L. C. Ehri, & R. Treiman (Eds.), Reading acquisition, (pp. 145–174). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Perfetti, C., Beck, I., Bell, L., & Hughes, C. (1987). Phonemic knowledge and learning to read are reciprocal: A longitudinal study of first grade children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 33, 283–319.

Peterson, M. E., & Haines, L. P. (1992). Orthographic analogy training with kindergarten children: Effects on analogy use, phonemic segmentation, and letter-sound knowledge. Journal of Reading Behaviour, 24, 109–127.

Porpodas, C. (1993). The relation between phonemic awareness and reading and spelling of Greek words in the first school years. In M. Carretero, M. Pope, R. J. Simons, & J. I. Pozo (Eds.), Learning and instruction, (Vol. 3, pp. 203–217). Oxford, UK: Pergamon.

Porpodas, C. (1995, December). How Greek first grade children learn to read and spell: Similarities with and differences from established views. Paper presented at the COST-A8 workshop on early interventions promoting reading acquisition in school, Athens, Greece.

Schneider, W., & Naslund, J. C. (in press). The impact of early phonological processing skills on reading and spelling in school: Evidence from the Munich longitudinal study. In F. E. Weinert & W. Schneider (Eds.), Individual development from 3 to 12: Findings from the Munich longitudinal study. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Snowling, M. J. (1980). The development of grapheme–phoneme correspondence in normal and dyslexic readers. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 29, 294–305.

Stanback, M. L. (1992). Syllable and rime patterns for teaching reading: Analysis of a frequency–based vocabulary of 17,602 words. Annals of Dyslexia, 42, 196–221.

Stanovich, K. E., Cunningham, A. E., & Cramer, B. R. (1984). Assessing phonological awareness in kindergarten: Issues of task comparability. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 38, 175–190.

Stanovich, K. E., Cunningham, A. E., & Feeman, D. J. (1984). Intelligence, cognitive skills and early reading progress. Reading Research Quarterly, 19, 278–303.

Stanovich, K. E., Nathan, R. G., & Zolman, J. E. (1988). The developmental lag hypothesis in reading: Longitudinal and matched reading-level comparisons. Child Development, 59, 71–86.

Stuart, M., & Coltheart, M. (1988). Does reading develop in a sequence of stages? Cognition, 30, 139–181.

Thorstad, G. (1991). The effect of orthography in the acquisition of literacy skills. British Journal of Psychology, 82, 527–537.

Treiman, R., & Chafetz, J. (1987). Are there onset- and rime-like units in printed words? In M. Coltheart (Ed.), Attention & performance XII (pp. 281–298). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Treiman, R., Goswami, U., & Bruck, M. (1990). Not all nonwords are alike: Implications for reading development and theory. Memory & Cognition, 18, 559–567.

Treiman, R., Mullennix, J., Bijeljac-Babic, R., & Richmond-Welty, E. D. (1995). The special role of rimes in the description, use and acquisition of English orthography. Journal of Experimental Psychology, General, 124, 107–136.

Treiman, R., & Zukowski, A. (1991). Levels of phonological awareness. In S. Brady & D. Shankweiler (Eds.), Phonological processes in literacy (pp. 67–83). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Tunmer, W. E., & Nesdale, A. R. (1985). Phonemic segmentation skill and beginning reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 417–527

Vellutino, F. R., & Scanlon, D. M. (1987). Phonological coding, phonological awareness and reading ability: Evidence from a longitudinal and experimental study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 33, 321–363.

Wagner, R. K. (1988). Causal relations between the development of phonological processing abilities and the acquisition of reading skills: A meta-analysis. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 34, 261–279.

Wagstaff, J. M. (1994). Phonics that work! New strategies for the Reading/Writing Classroom. New York: Scholastic.

Walton, P. D. (1995). Rhyming ability, phoneme identity, letter-sound knowledge and the use of orthographic analogy by prereaders. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87, 587–597.

White, T. G., & Cunningham, P. M. (1990, April). Teaching disadvantaged students to decode by analogy. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Boston.

Wimmer, H. (1993). Characteristics of developmental dyslexia in a regular writing system. Applied Psycholinguistics, 14, 1–33.

Wimmer, H., Landed, K., Linortner, R., & Hummer, P. (1991). The relationship of phonemic awareness to reading acquisition: More consequence than precondition but still important. Cognition, 40, 219–249.

Wimmer, H., Landerl, K., & Schneider, W. (1994). The role of rhyme awareness in learning to read a regular orthography. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 12, 469–484.

Wise, B. W., Olson, D. K., & Treiman, R. (1990). Subsyllabic units as aids in beginning readers’ word learning: Onset-rime versus post-vowel segmentation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 49, 1–19.

Wylie, R. E., & Durrell, D. D. (1970). Elementary English, 47, 787–791.

Yopp, H. K. (1988). The validity and reliability of phonemic awareness tests. Reading Research Quarterly, 23, 159–177.

__________

1These two word types were matched for lower-level orthographic frequency using positional bigram frequencies.

2This description somewhat simplifies the comparisons that were possible, as we could not derive monosyllables with unfamiliar rimes in Greek. The Greek data are taken from longer nonsense words with familiar versus unfamiliar spelling patterns for the rhyming portions of the words. The English and French data are from monosyllables, as described in the text.

3More detailed descriptions of how to use rime analogies in the classroom can be found in Phonics That Work! by Janiel Wagstaff (1994), and Phonics They Use, by Patricia Cunningham (1992). A special set of stories for teaching clue words and their associated rime spelling patterns has been devised by Rod Hunt for the Oxford Reading Tree Rhyme and Analogy Programme, edited by Usha Goswami (1996).