CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION TO WAREHOUSING

1.1 Warehousing Through the Years

I wrote the first edition of World-Class Warehousing in 1995. Back then, people asked me why I was writing a book on warehousing when the just-in-time (JIT) movement was aimed at eliminating warehousing. Today, it’s the lean movement. The question is a legitimate one and one I ask seminar attendees every time I teach a warehousing seminar. “Why should we devote our time and energy to studying an activity that every supply-chain professional and the lean literature is trying to eliminate?” A better question might be, “In what ways does warehousing add value in business and in supply chains?” If we can’t come up with good answers, then writing this book really was a waste of time, and reading it likewise. As we will see, warehousing plays an indispensable role in business and supply-chain strategy.

Warehousing in the Supply Chain

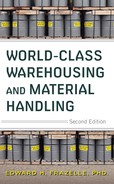

I developed the RightChain model in the mid-1990s. The model integrates and optimizes walks through the five components of supply chain strategy: customer service, inventory management, supply, transportation, and warehousing. Through those eyes, the value of warehousing is demonstrated in each component clearly visible (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 RightChain supply-chain logistics model.

Warehousing and Customer Service

Warehousing adds value in customer service, by facilitating high inventory availability, shorter response times, value-added services, returns, customization, and consolidation among others.

Fill rate is the portion of a customer’s demand satisfiable from on-hand inventory. In most cases, a significant investment in safety stock is required to provide high customer fill rates. That safety stock must be housed somewhere, and that somewhere is typically a warehouse.

Warehouses in close proximity to the customer base and with short internal cycle times help to reduce response times to customers. We have one client that provides same-day delivery of critical service parts via a nationwide network of small warehouses with short order cycle times. One of our financial services clients supports its financial analysts with small warehouses located in the centers of major financial districts, serving offices via subway, courier, walking, and bicycles. One of our convenience store clients is improving product freshness by increasing delivery frequencies to its 14,000 stores supported by a major increase in the number and capacity of its warehouses and distribution centers.

Following the mass customization movement, the likelihood that an order will require customization in some form is increasing exponentially. The ability to execute the requisite value-added services such as custom labeling, special packaging, monogramming, kitting, coloring, and pricing is and will continue to be a competitive supply-chain differentiator. Warehouses are uniquely equipped with the workforce and equipment to execute these value-added services. In addition, by holding the noncustomized inventory and postponing the customization, overall supply chain inventory levels may be reduced. As the physical facility closest to the customer location, a warehouse is also a natural place to customize, kit, assemble, or countrify products in accordance with the principle of postponement—minimizing overall inventory investments throughout a logistics network by delaying customization. For example, one of our health and beauty aids clients puts its shampoo in blank bottles for storage. Once an order is confirmed from a specific country, the labeling required for that specific country is applied in line with the picking and shipping process.

One customer service is foundational to our culture’s expectations of logistics systems but taken for granted is consolidation. For example, if you order a shirt and a pair of pants from a mail-order company, rarely would you want the shirt showing up one day in one package and the pants showing up another day in another package. For those items to show up at the same time in the same package, they most likely need to be housed under the same roof, that is, in a warehouse.

Returns constitute another customer service facilitated by good warehousing practice. Convenient and inexpensive returns for customers yield higher sales and customer satisfaction ratings. Warehouses and distribution centers are typically already located in close proximity to the customer base and have the workforce and material-handling equipment uniquely suited to handling returns.

Although not directly considered a customer service, in many parts of the world, physical market presence is an important cultural competitive differentiator. Warehouses and distribution centers are well-recognized means of establishing physical market presence.

Warehousing and Inventory Management

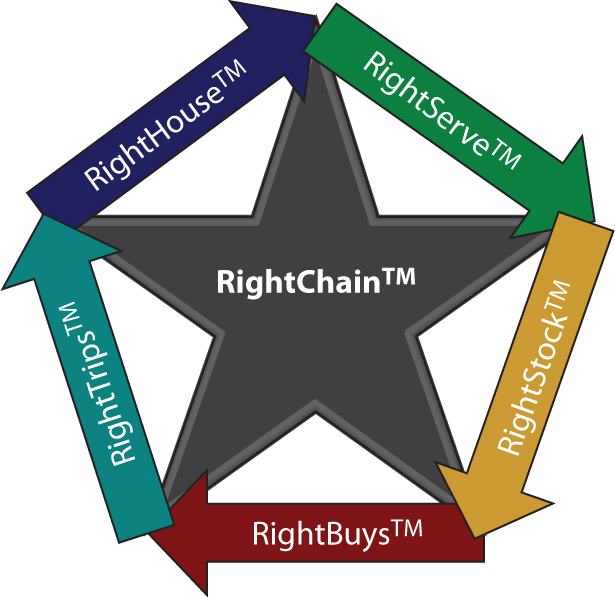

Because warehouses house inventory (or wares), warehousing adds business and supply-chain value in all the same ways as inventory. Warehouses and their inventory facilitate production economies of scale, optimize factory utilization via seasonal inventory builds, and mitigate supply-chain and business risk by holding contingency and disaster inventory. Despite all efforts to reduce setup and changeover costs and time, there will always remain expensive and time-consuming setups. In those situations, it would be economically foolish to produce short runs. When long production runs are economical, the resulting lot-size inventory must be housed, most effectively in a warehouse. For example, one of our large food and beverage clients was running lot sizes 50 percent below optimal, incurring excessive changeover and production costs as a result. To correct, an additional 150,000 square feet of warehousing space was required, yielding a significant return on investment to their business Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Coca-Cola’s distribution center near Raleigh, North Carolina, with expanded warehousing square footage to accommodate larger lot sizes and an optimal activity density.

Many corporations have significant peaks and valleys in their demand. One of our clients, Hallmark Cards, is an extreme example. Most of the demand for greeting cards falls in the Christmas and Valentines seasons. If the company’s production capacity was designed for those peaks, its production capacity would be cost prohibitively underutilized most of the year. To balance the production and optimize supply-chain costs, Hallmark produces greeting cards at a fairly balanced pace during the year, resulting in a large storage requirement for most of the year. This seasonal inventory is stored in the large warehouse, in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 Hallmark Cards’ warehousing complex in Liberty, Missouri. The facility is sized to accommodate inventory buildups in support of extreme seasonal peaks.

The Schwan’s Food Company is another one of our clients. One of its flagship products is frozen pie. The company is the world’s largest manufacturer of frozen pies, most of which are consumed between Thanksgiving and Christmas. As is the case with Hallmark, to optimize Schwan’s supply-chain costs, the company must balance production throughout the year and use third-party frozen warehousing to hold the seasonal buildup in inventory from January through September.

Contingency and disaster inventory insures against unexpected situations outside the realm of those covered by traditional safety-stock inventory. Such situations include natural disasters, labor strikes, and other abnormal supply-chain disruptions. For example, in our work with telecommunications and utilities clients, we often plan for contingency and disaster inventory to maintain service in the increasingly likely event of hurricanes, floods, and snowstorms.

Warehousing and Sourcing

One of our clients is one of the world’s largest chocolate candy companies. Of course, the main ingredients are cocoa and sugar. In addition to production, those raw material costs also make up most of the total landed product cost. To help determine the optimal timing of the purchase of sugar and cocoa, the company maintains advanced proprietary weather-forecasting systems and sophisticated predictors of the future price of sugar and cocoa. When our client believes that the price is optimal, it may literally buy boatloads of sugar and cocoa. That sugar and cocoa must be housed somewhere, and that somewhere is a warehouse.

After raw materials, the next most expensive cost component of the company’s total landed cost is production. To help keep those costs low, the company operates with extremely long production runs. Because margins are high, inventory carrying rates are low, the risk of obsolescence is low (I have never personally refused a candy bar because of technical or packaging obsolescence), and shelf lives are long, total landed supply-chain costs are optimized with long production runs. Those long production runs create large batches of inventory that must be housed somewhere. That somewhere is a warehouse.

Another means by which companies seek to reduce material cost is low-cost foreign sourcing. The likelihood of an order entering or departing the warehouse from/to another country has never been higher. Warehouses add significant value in the supply chain by facilitating the efficient inbound and outbound processing of international orders. One example is our client, Payless Shoes, one of the world’s largest shoe retailers and global importers. Most of the company’s shoes are imported from China and arrive in the United States via the Port of Long Beach. Goods arriving there are transloaded into 53-foot containers and trucked to the company’s West Coast distribution center in Redlands, California, or the company’s East Coast distribution center near Cincinnati, Ohio. Similar West Coast distribution center missions are carried out by the massive concentration of distribution centers in or near Redlands known as the “Inland Empire.” A similar empire of distribution centers has grown up around the Port of Savannah, Georgia, where The Home Depot, Ikea, and Pep Boys, among many others, inject imported products into their East Coast logistics networks (Figures 1.4 through 1.7).

Figure 1.4 The “Inland Empire” is approximately one hour’s drive from the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles, located at the crossroads of major interstates I10, I15, and I215, and is home to a high-quality workforce. It is also home to perhaps the world’s largest concentration of warehouses.

Figure 1.5 Aerial view of a concentration of warehouses and distribution centers in the “Inland Empire”.

Figure 1.6 Aerial view of Payless Shoes’ West Coast distribution center (Redlands, California).

Figure 1.7 East Coast “Inland Empire” (Savannah, Georgia).

By postponing title transfer, on-site vendor-managed inventories are another means by which warehousing can add value in business and supply-chain logistics. Figure 1.8 shows one of our mining client’s maintenance parts vendor management inventory warehouse locations. The warehouse is located near the large maintenance shops in one of the world’s largest copper mines.

Figure 1.8 Rio Tinto’s vendor management inventory warehouse in support of maintenance operations for its Kennecott copper mine located outside Salt Lake City, Utah.

Warehousing and Transportation

As supply chains reduce inventory by shipping more frequently in smaller quantities, warehouses can help to provide transportation economies of scale by working as consolidation points for accumulating and assembling small shipments into larger ones, less-than-truckload shipments into full truckloads, less-than-container-load shipments into full container loads, transloading 40-foot containers to 53-foot containers, and so on (Figure 1.9).

Figure 1.9 Transloading is the transfer of cargo from 20- or 40-foot ocean containers into domestic 48- or 53-foot trailers. Depicted is Pep Boy’s East Coast transload facility located near the Port of Savannah, Georgia.

A frequently overlooked transportation expense is customs duties. Bonded warehouses allow consignees to delay duty payment until their goods are withdrawn from the bonded warehouse. Bonded warehouses located in free-trade zones also permit in-transit goods to pass through without duties being charged at all.

Warehousing and Warehousing

The fifth and last set of RightChain supply chain strategy decisions has to do with warehousing. It’s my personal favorite, but I have to admit that it’s the last logistics activity that should be considered when developing a supply-chain strategy. First, a clever trip through the first four RightChain initiatives may eliminate, should minimize, and will correctly determine the need for warehousing as opposed to letting the warehouses play their normal role of being the physical manifestation of the lack of supply-chain coordination, integration, and planning. Second, the warehouse is like a goalie in a soccer game. Like it or not, it’s the last line of defense and needs to be designed accordingly. Third, we need the customer-service, inventory management, supply, and transportation mission requirements from the supply chain strategy to properly plan and operate the warehouse.

Thus, despite all the initiatives of e-commerce, supply-chain integration, efficient consumer response, quick response, lean Six Sigma, and JIT delivery, the supply chain connecting manufacturing with end consumers will never be so well coordinated that warehousing will be eliminated completely. In fact, the length of supply chains owing to global sourcing and the potential for disruption as a result of increasing numbers and severity of climatic and security incidents are increasing the need for warehousing and the value warehousing adds in businesses and supply chains. As all these disruptions take hold, the role and mission of warehouse operations are changing and will continue to change dramatically.

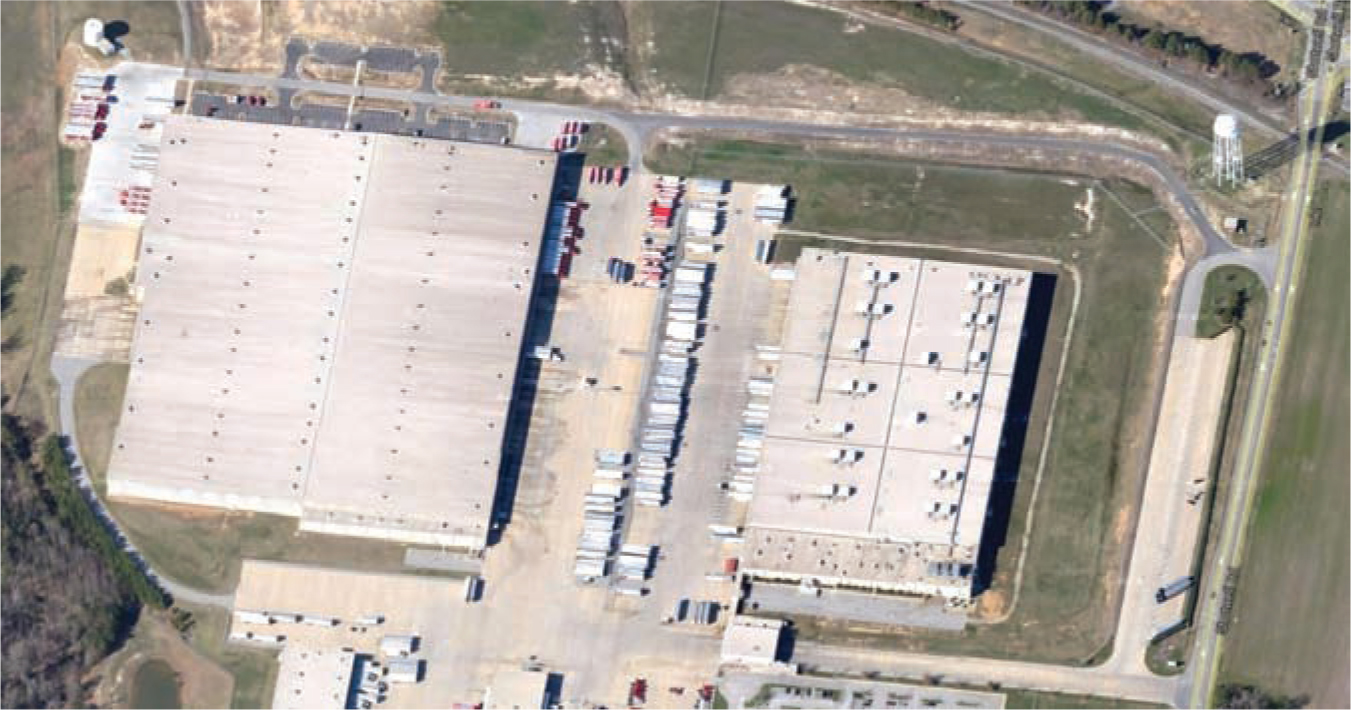

1.1 Warehousing Through the Years

Warehousing has evolved from a simple activity devoted primarily to material storage in the 1950s and 1960s (Figure 1.10). With the adoption of JIT principles in the 1970s and 1980s came smaller order sizes more often, less inventory, and a greater need for order-assembly activities occupying the space made available by inventory reductions. Warehouses were transformed into distribution centers, beginning the reimaging of warehousing from a career-killing profession to a career-making profession. With the adoption of postponement, mass customization, supply chain integration, and global logistics in the 1990s, a number of cross-docking and value-added service activities were added in the warehouse. Logistics centers were created out of distribution centers, combining customized labeling and packaging, kitting, international shipment preparation, customer-dedicated processes, and cross-docking with the traditional activities of storage and order assembly. The distinctions between manufacturing, transportation, and warehousing activities blurred. The margin for error is minimal (Figure 1.10).

Figure 1.10 Warehousing through the years.

All these changes accumulate to put warehouse managers in duress. Under the influence of e-commerce, supply-chain collaboration, globalization, quick response, and JIT, warehouses today are being asked to

![]() Execute more smaller transactions

Execute more smaller transactions

![]() Handle and store more items

Handle and store more items

![]() Provide more product and service customization

Provide more product and service customization

![]() Offer more value-added services

Offer more value-added services

![]() Process more returns

Process more returns

![]() Receive and ship more international orders

Receive and ship more international orders

At the same time, warehouses today have

![]() Less time to process an order

Less time to process an order

![]() Less margin for error

Less margin for error

![]() Fewer young, skilled, native-speaking, literate personnel

Fewer young, skilled, native-speaking, literate personnel

![]() Less warehouse management system capability (a by-product of Y2K investments in enterprise resource planning systems)

Less warehouse management system capability (a by-product of Y2K investments in enterprise resource planning systems)

I call this rock-and-a-hard-place scenario the plight of the warehouse manager. Never has the warehouse been asked to do so much and at the same time been so strapped for resources. This makes it even more important to understand the fundamentals and best practices of warehousing. Such an understanding begins with a basic classification of the roles of warehousing in a logistics network.

1.2 Warehousing Fundamentals

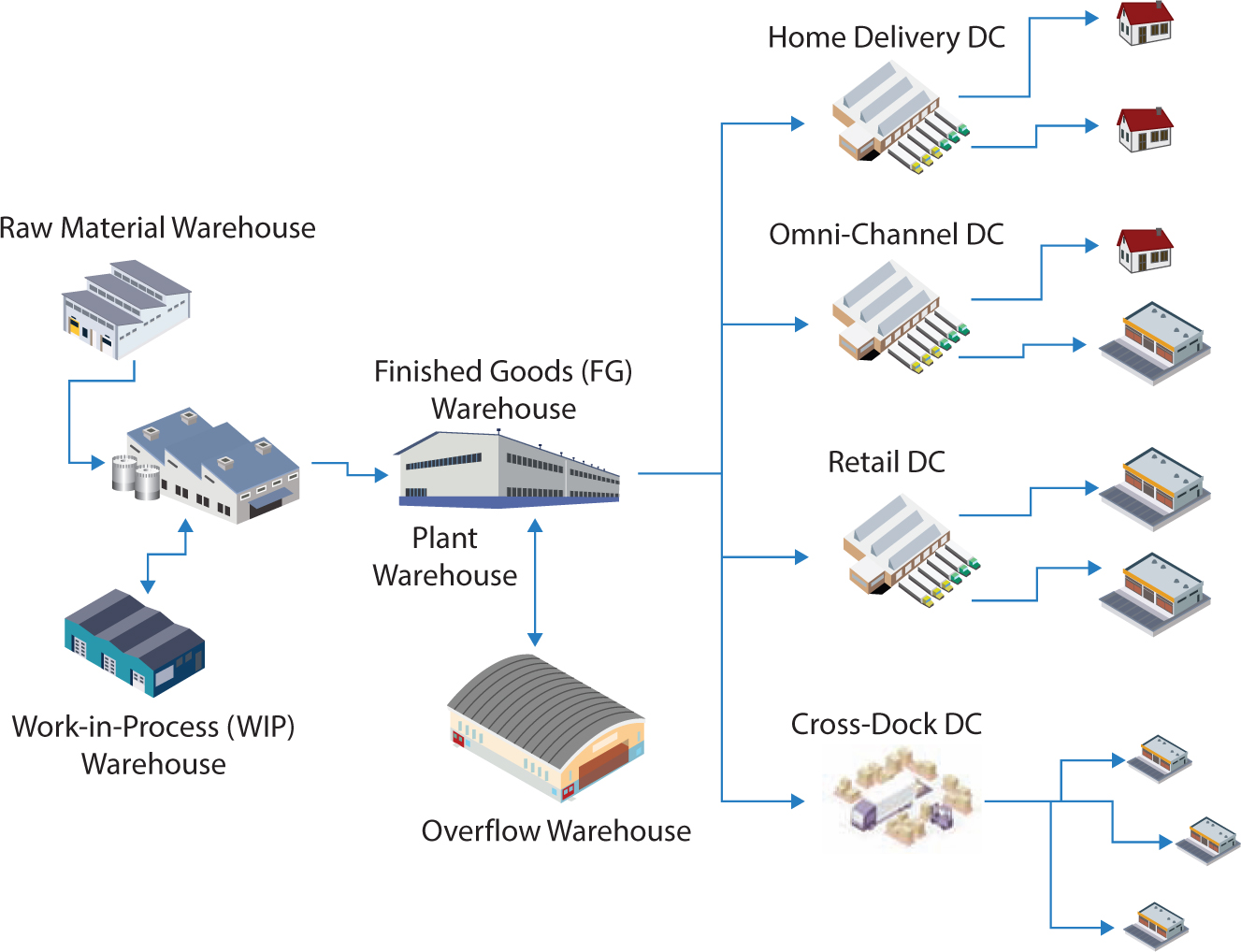

Warehouses are not disappearing but continue to play many valuable business and supply chain roles. Those roles have names (Figure 1.11).

Figure 1.11 The role of the warehouse in the logistics chain.

Raw material warehouses hold inventory near or in factories where the timely support of production and assembly schedules is the key to success.

Work-in-process warehouses hold inventory in or near factories and serve primarily as variation buffers between production schedules and demand.

Finished-goods warehouses (or plant warehouses) typically hold large quantities of finished goods awaiting deployment to distribution centers.

Overflow warehouses are typically located near plant warehouses often hold seasonal inventory and are frequently operated by a third party. Nearly two-thirds of all plant warehouses have overflow warehouses.

Distribution center warehouses are located much closer to the customer base than are plant warehouses. Distribution centers typically receive product from many plant warehouses and serve customers with same- or next-day delivery. The delivery point for the distribution center determines its name. Home delivery distribution centers deliver to homes. Retail distribution centers deliver to retail stores. Omni-channel distribution centers deliver to a mix of homes and retail stores. Cross-dock distribution centers do not hold product but simply mix and sort.

Bonded warehouses typically sit inside free-trade zones and facilitate delayed duty payments.

Public warehouses are operated by third parties and are open to the public for what are typically short-term storage agreements.

Contract warehouses are operated by third parties and typically are dedicated to single users for extended periods.

Retail back rooms, tool cribs, storerooms, and parts lockers are also forms of warehouses that do not carry the warehousing name (Figures 1.11 through 1.13).

Figure 1.12 Plant finished-goods and raw-materials warehouses supporting H.P. Hood’s Winchester dairy plant.

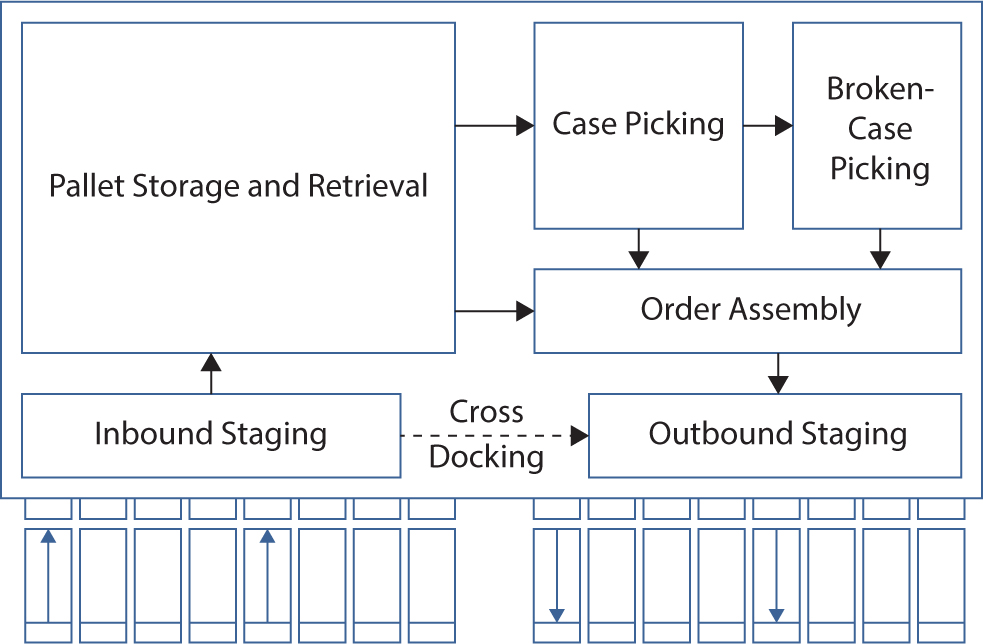

Figure 1.13 Traditional warehouse process flow.

Although the roles and names of warehouses may differ, the internal activities are remarkably similar. Those activities include the following:

1. Receiving is the collection of activities involved in (a) the orderly unloading and receipt of all materials coming into the warehouse, in (b) providing the assurance that the quantity and quality of such materials are as ordered, and in (c) disbursing materials to storage or to other organizational functions requiring them. Prepackaging is an optional activity that is performed in a warehouse when products are received in bulk from a supplier and subsequently packaged singly, in merchandisable quantities, or in combinations with other parts to form kits or assortments. An entire receipt of merchandise may be processed at once, or a portion may be held in bulk to be processed later. This may be done when packaging greatly increases the storage-cube requirements or when a part is common to several kits or assortments. Cross-docking is moving inbound material directly from the receiving dock to the shipping dock, essentially filling orders from receiving.

2. Put-away is the act of placing merchandise in storage. It includes moving material to and placing material in assigned put-away locations.

3. Storage is the physical containment of merchandise while it is awaiting a demand or until it is released from quarantine. The storage method depends on the size and quantity of the items in inventory and the handling characteristics of the product and/or its container. We characterize storage systems as pallet storage systems, case storage systems, and broken-case storage systems.

4. Order picking is the process of removing items from storage to meet a specific demand. Order picking is the basic service a warehouse provides for its customers, and it is the function around which most warehouse designs are based.

5. Shipping typically includes

a. Sorting batch picks into individual orders and accumulating distributed picks into orders (This must be done when an order has more than one item and the accumulation is not done as the picks are made.)

b. Checking orders for completeness and accuracy

c. Packaging merchandise in an appropriate shipping container

d. Preparing shipping documents, including packing lists, address labels, and/or bills of lading

e. Weighing and cubing shipments to determine shipping charges

f. Accumulating orders by outbound carrier

g. Loading trucks

1.3 How to Read This Book

World-Class Warehousing and Material Handling is a journey through our RightHouse principles and practices required to execute each warehouse activity at a world-class level. First is RightViews, warehouse activity profiling, the data and pattern recognition required to quickly and objectively reveal opportunities for simplification, process integration, and process automation. Second is RightScores, warehouse performance, cost, and value measures, where we will consider financial, productivity, utilization, quality, and cycle-time metrics and how to use them in justifying new warehouse projects. Third are RightIns and RightPuts, aimed at optimizing receiving and put-away. There we will study cross-docking, direct put-away, directed put-away, dock optimization, prereceiving, and interleaving. RightStore, discussed in Chapters 5, 6, and 7, presents systems and best practices for optimizing pallet storage and retrieval, case storage and picking, and broken-case storage and picking. RightPick and RightShip present principles and practices to optimize order picking and shipping. RightPaths presents our seven-step methodology for optimizing warehouse layout and material flow. RightComms concludes the book with a presentation of the latest warehouse communication systems.

Our RightHouse principles were developed during a retrospective review of hundreds of warehousing projects, including greenfield warehouse designs, warehouse layout designs, warehouse operations benchmarking, warehouse process improvement, and warehouse management systems design and implementation in literally every part of the world. The common denominator in those breakthrough process improvements is the elimination and simplification of work content. To the extent to which you can eliminate and simplify that work content, you will be successful in your pursuit of world-class warehousing.