8 Ways of finding out

The media have no choice but to ask questions of the government of the day or the state of the moment, not because they are special, not because they are better, not because they are arrogant, not because they are self-appointed, but because if they do not do it, nobody else will. (John Tusa, former Managing Director of the BBC World Service)

We have established that the basic skill of journalism is reporting – collecting and giving the facts – and that their news value consists in the facts being of public interest and sometimes in the public interest. Reporters have to identify the information that has news value, locate reliable sources of information, gather accurate (verified) information and communicate it accurately, effectively and quickly. The last requirement means that they fulfil the other objectives as well as they can within the deadline.

Feature writers must build on those skills. They may have more time, deadlines may at times be extended, and they may have less excuse for unverified data. They normally add to the reporting skills greater language skills in order to describe, analyse, argue and persuade, but these are the concerns of other chapters. This chapter concentrates on the techniques that will help you to employ to good effect:

• reliable sources

• an interviewing strategy

• verification skills.

RELIABLE SOURCES

Which are the best sources for your purpose? I presume you have a provisional title before you start gathering and know what you’re looking for. The first thing to do is find out as much as you can about the topic of your feature so that you will be able to ask fruitful questions (those that get fruitful answers), and so that you will understand what interviewees are talking about and make illuminating comparisons. That study may benefit from your own personal experience and legwork.

It’s worth reminding yourself, in the course of research, of the truism that you may be able to leave out things you know without spoiling your story, but if you leave something out because you don’t know it, there will be a hole in the story.

For anything complex you may be able to get fairly detailed briefing and recommended sources from a commissioning editor.

Background study

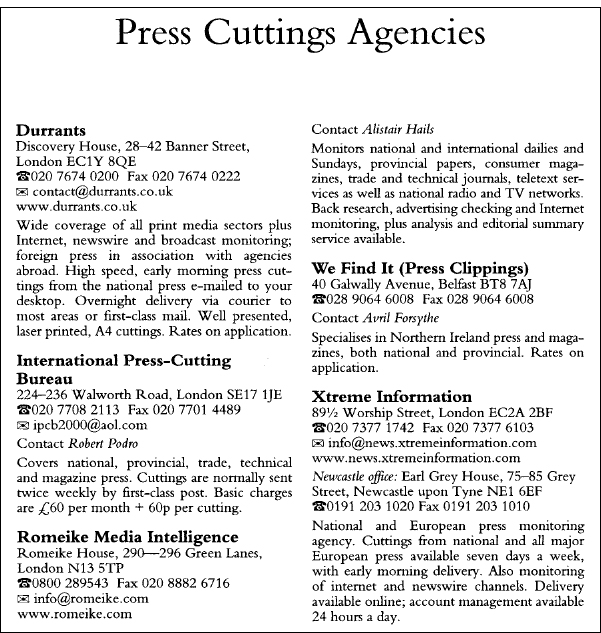

First see what you’ve got in your cuttings files. If they are lacking, you may want to make use of a press cuttings agency (see Figure 8.1.) but they can be expensive. Try informal exchanges – your friends and colleagues, and chatrooms. Move around with a reporter’s notebook. You may get something out of broadcast programmes and sometimes background information can be acquired from producers or press offices. Note that TV programmes may have been a year in the pipeline.

You can then decide what reference materials and the Web can’t tell you that an interviewee can, who you would like to interview, and what questions you need or want to ask.

Information is now so easily available via the Internet that it’s less necessary to travel and incur other expenses to gather it. For example, whereas 10 years ago you might have paid a colleague in Glasgow to do some on-the-spot research to give you notes on the Scottish aspects of your subject, or organized a network of colleagues exchanging such services, or inserted classified adverts asking for information, you’d be more likely today to go to the Web, to a newsgroup or chatline or to publications or services online. It will be worth subscribing to some publications and services online that deal with your specific interests. But avoid becoming deskbound.

Personal experience and legwork

If your magazine piece for a woman’s magazine is to describe how the headmaster of your local primary school rescued it from the bottom of the league table you might start by thinking about your own schooldays, and about the current experiences of your children or of children you know. Then you might read newspaper and magazine features on the national picture (consult the BHI and other indexes of articles published). You might follow that up with legwork – a visit to the school and the area to see what you can observe for yourself – and interviews with the headmaster and some of the children. You might fill up with some information about the area’s schools in general from the Local Education Authority (press releases?, booklet?, reports?).

Figure 8.1

Ways of finding out: Press Cuttings Agencies from The Writer’s Handbook 2005. © Macmillan Publishers Ltd., 2004, ed. Barry Turner

From legwork report to legwork feature

Supposedly filed from the war zone in Iraq, reports in the New York Times from an American journalist were concocted in the US on his computer.

Assume you’ll also be found out if you fake legwork or misrepresent any of your sources. The temptation to use the resources of the computer instead of legwork increases. Naturally so, since for some purposes the Internet is vastly superior. You can speedily collect case studies to illuminate your theme that might have required time-consuming legwork and telephone calls: the informal kind from chatroom discussion, and formal ones out of the reports from professional journals that are reproduced online.

Harold Evans, editor of The Sunday Times when it produced acclaimed investigative journalism about such scandals as the deformities caused by the drug Thalidomide, has said: if only we could have used chatrooms at that time. Don’t be too ready, however, to advertise yourself as a journalist in a chatroom – you could be frozen out.

Avoid being too dependent on Internet sources (and make sure you know exactly what you’re looking for when you go online). Getting out of the house or the office to talk to flesh and blood people should be done more often by feature writers as well as reporters. And sometimes, if you can pardon the pun, you can make a feature out of it. You might have the time and inclination to combine personal experience (literally) with legwork to argue a case and it may be the best way to do it. Let’s call it a legwork feature.

It’s a year or two ago now, a newspaper reported that you could earn up to 7.00 an hour on the streets of Aberdeen as a ‘bogus beggar’. It was said that in London you could earn £100 a day and that many did. Police departments, town councils and charities come up with such figures from time to time. Steven Bowron in The Sunday Post of Dundee recounted an attempt to find out what it’s like to beg. In tattered clothes and a cardboard notice (‘hungry and homeless’) he collected, as well as taunts, £3.13 in eight hours outside Euston Station in London (and somewhere else when moved on by the police). It was a drizzly day.

He talked to Shelter Scotland whose advice to people who wanted to help beggars genuinely in need was to give to the various charities concerned with the homeless. Well, in terms of getting to the truth, Mr Bowron’s experience was useful in the casting of doubt on the assertions of the no-nonsense brigade and in getting across the miserable experience begging is, and in a sense that was getting a little nearer to the truth. He didn’t make any greater claims than that.

The above account shows how careful you have to be when figures are involved. How were those original figures arrived at? How large were the samples? As for Mr Bowron’s winnings, if he had done a week on the street, might he have collected more than one day’s takings suggested? Could he have got better at it? Was the weather responsible for people hurrying past? Do you have to build up a presence before people start giving? Be a particular shade of grey? And so on.

You will compound any problems of interpretation if you fail to take notes and quotes accurately. Ask your interviewee to repeat anything you’re not sure of. Was that ‘fifteen’ or ‘fifty’? Would you spell that name please?

Another variation of the case-study feature was ‘You can’t judge a woman by her cover’ in You, the lifestyle magazine of The Mail on Sunday. It was experimental theatre of a kind. The writer, Joan Burnie, accompanied model Trudie Joyce to London establishments: on two shopping expeditions to Harrods, two trips to the American Bar at the Savoy and two trips to the nightclub Stringfellows. For each visit Trudie dressed in different clothes, once as a slag and once elegantly.

The contrasting reactions of employees – doormen, sales assistants, waiters, barmen, barmaids and of the public – make an amusing account ‘in the interests of sexual science and journalism’. Colour pictures of the model in different clothes and situations reinforce the thesis expressed in the title, together with suggestive captions. The thesis, you might argue, is imposed on the material rather than supported by it. Readers may guess that other encounters that didn’t fit were omitted. But the first-hand experiences have impact and readers will accept the general psychological truth about human nature behind it all.

Selection of contacts

Collect good contacts as you go, for the features you write, in your own contacts book. You may find a filofax type of book ideal. One contact leads to another. Before you leave a contact, ask ‘Who else shall I talk to?’ Indicate the particular expertise of your contacts (‘good on progress of Parliamentary bills’). Include such entries as libraries, their specialisms, hours of business and the names of friendly librarians. Press Gazette produces an electronic database and regularly lists press officers.

Get on the mailing list of organizations you’re interested in so that you will receive advance information about developments. Manufacturers will send you handouts and free photographs if you write about new products.

Official sources may be generous with time and information, especially if they know your work and if you have established good relationships. But talk to enemies as well as friends, consumers as well as producers.

When you’ve collected a fair number of contacts in your contacts book (many of whom will be experts in the particular subjects you cover), you might well start your research planning for a feature with one of them. If they don’t know what’s the current situation, the latest development (or problem), they may be able to put you on the right track quickly, point you to the latest book or features or most knowledgeable source.

Assessment of sources

There are three essential criteria by which your sources must be judged. Are they accessible; are they, where necessary, multiple; are they the best informed?

Are they accessible? If your feature would benefit greatly from your visiting an institute in New York or Paris, there may not be time and expenses might not be agreed. Think of alternative sources.

Multiple? How authoritative are your sources? Some eyewitnesses remember certain things, others remember other things. Figures given in press accounts can be wrong and the errors repeated. Cross-check one kind of expert against another.

But which are the best informed, the most credible, the most reliable? This requires some thought. The traps are endless. There are unreliable sources whose judgement is clouded or whose memory is impaired. There are hoaxers who delight in ringing up newspapers to give them false stories. There are convincing gossipers, liars, slanderers, people bearing grudges, seeking revenge at any cost. There’s a limit to how much cross-checking you can do, so you must select with care. When you’re not sure of the truth of statements you can attribute them in a qualified way: ‘Certain people believe that …’ or ‘The impression has been gaining ground that …’

For a feature about bullying in the workplace you wouldn’t depend on an interview with one victim, but would supplement it with other interviews, with observers for example, and with some reading about the subject. Look for the names of experts in encyclopedia articles and recent books on your subject. Circle names of experts quoted in published features or check them out in your local library. Trade magazines (business to business) contain the names of experts in many fields. If you want a wide choice of experts find them by going online and typing in your search terms. Experts depend on being recognized as such and will grant interviews readily (if you pitch your request for one effectively).

Sometimes you can find a disaffected expert ready to tell you more than a happy one. Why are there such long delays in, say, hip replacement operations? The happy hip replacement surgeon in your local hospital may give you an interview. But you may find some questions unanswered or avoided and you may find a whistleblower to complete the picture. One such whistleblower, also a surgeon doing hip replacements, complained that a fellow surgeon was admitting private patients before NHS patients who had waited longer and was getting paid twice. The NHS Trust decided that she needed further training.

It was two years later that she was interviewed by a journalist. She had done six months further training, after which no more training had been available and she had been on full pay for two years. She had seen no patient in this period and wanted her job back. Of course, the truth isn’t a simple matter. Does the other side have more of a case than you suspected? Find another source to check.

You can assess a contact’s reliability from the replies to questions to which you know the answer. You know for certain, let’s say, that your contact’s firm has had to withdraw three products this year after being arraigned under the Trade Descriptions Act. But you ask, ‘Sometimes in your business firms have trouble keeping in line with the Trade Descriptions Act. Has that ever happened to your firm?’ Your readers must make their own judgements about how reliable your contacts are, and your questions and treatment should establish their confidence in your judgement.

You can be over-cautious in choosing the obvious experts. They may have been overused elsewhere. Remember that the best stories can come from an unusual angle and that can come from matching your topic with one or two out-of-the-way sources, as described in Chapter 3.

In your feature don’t neglect to give sources of official figures and of unusual information, facts that might be queried, so as to lend them authority.

AN INTERVIEWING STRATEGY

For a productive interview for information you need to:

• make effective approaches

• organize your notes

• question creatively

• use techniques of persuasion

• elicit good quotes

• choose the best method

• acknowledge your sources

• establish bonds with your contacts.

Effective approaches

Don’t depend on switchboard operators to guide you to a likely source of information. Work out from your initial study the name and job title of a likely contact.

If you’re not known or haven’t got a commission from a well-known publication it can be difficult to get past the secretaries, assistants, deputies, the various kinds of gatekeepers. It helps if you can engineer an introduction, something like: ‘Brian so-and-so suggested you might be able to tell me about …’.

Decide which method of interview would be most appropriate for your subject but be ready to go along with the preference of your contact. Explain the project you’re working on and why your contact’s contribution would be important. If there is reluctance, remember you’re giving free publicity.

You may be able to indicate (tactfully) in what way the published interview will benefit the contact and their work, and that a ‘no comment’ might be harmful. Tell people you want to ‘talk’ to them, not ‘interview’them. Don’t get annoyed if in spite of tactful persistence you fail to gain an interview. It happens to the best of us. Be ready with alternatives.

Dos and don’ts

Suppose you, fairly new to the game, are asked on Monday to find out why a renowned editor and several other staff had just mysteriously resigned from a highly successful magazine, and to write a feature about the magazine, explaining its success and what has gone wrong. Your deadline is Thursday, 1000 words. You’ve been given by your editor the name of the most promising contact, let’s call him Arnold Baxter, a journalist who worked with the proprietor for 15 years and left six months ago to become the director of a School of Journalism. You have an interview on Tuesday with the Advertisement Director of the group, who will tell you something of the group’s history and in particular the history of the magazine in question.

What you shouldn’t do

You fix up a telephone interview with Mr Baxter for the Monday. You haven’t had time to get acquainted with the magazine – it’s not one you’re familiar with – but you decide you’ll do that after the Tuesday interview. Mr Baxter is surprised to discover that you know nothing at all about the magazine, nor its history, nor anything about the resignations. You say he’s your first interview and that you’ll fill in the details from your Tuesday interview. He suggests you find out about these things, do the Tuesday interview and return to him on Wednesday. But now that he’s on the end of the phone you want to make the most of it so you plough on: what was it like working with that proprietor and why do you think things have suddenly gone wrong with so many of the staff?

Mr Baxter is very articulate and talks quite quickly. You’re writing it all down but you have to ask him to pause frequently. You wish you’d learnt shorthand. Mr Baxter is sympathetic at first but becomes frustrated by the constant need to pause and is anxious to get the interview over. You can’t expect an interviewee to talk at the speed at which you write longhand.

‘Can I see the script?’ asks Mr Baxter, worried that you’re going to misquote him. You say it’s not the policy of your magazine to show interview scripts before publication. At least, read over to me from your final script what you’re quoting me as saying, he says. I’ll check with my editor, you say. The interview ends with little rapport and you have lost a good opportunity to obtain illuminating commentary. When you’ve gone Mr Baxter realizes that you have failed to ask the specific kinds of questions that would have produced that illumination. Such as: what problems did you have with the proprietor while you were an employee? You can’t expect an interviewee to tell you what questions should be asked. You recognize that you’ve done a duff interview, but Mr Baxter regrets that he’s too busy to give you another chance.

What you should do

1 Find out as much as you can about Mr Baxter, probably by interviewing briefly one or two others first. Ask the editor why he’s the main prospect if you weren’t told. Talk to any current or ex-colleague who knows Mr Baxter well. Decide on two or three main interviewees and the best order to interview them.

2 Buy at least the current issue of the magazine and read some of it so that you know what it’s all about, what sort of audience it has, etc., and look through the others in the group. (Access them online or in a good library.)

3 Find any recent articles about the company and about the magazine in particular.

4 Find out as much as you can about Mr Baxter’s career with the company and his relationship with the proprietor.

5 Since you have no shorthand, ask for permission to tape the interview, via a telephone hook-up. I have found that most interviewees welcome it, feeling there’s less chance of being misquoted. (Of course, it doesn’t always work that way because you’ll do a little editing when transcribing and that may result in the interviewee feeling misrepresented. Some interviewees will tape the interview at their end.) If you are asked not to tape, you should do a crash course in shorthand.

Organize your notes

Poorly organized notes can cause much trouble when it’s time to write the piece. Here are a few essentials.

You may want to use separate sheets or cards for separate themes. You can then experiment by shuffling them into different orders when you want to produce an outline. Whatever the source of your notes, keep in mind that the published article must get the acknowledgements right. Indicate name of interviewee and date of interview or event; and authors and titles of books and articles, dates of publication, and page numbers for the references so that you can verify later that you’ve quoted or reproduced statements correctly. Back up points that need an authority by acknowledging the source. Well-known facts don’t need acknowledgement.

Note sources for figures, especially official figures, to give them authority. Date everything: not only those mentioned above, but also any event mentioned in the course of conversation. If your interviewee says something happened ‘recently’, ascertain the date so that you’ll know how you (or a subeditor) will refer to it on the date your piece is published. Inaccurate notes can bring trouble.

Quoting and paraphrasing

Put quote marks in your notes round significant statements. You may want to use the quotes in your feature. You may want to establish the credibility of a statement made by an expert. If you quote and attribute factual statements that might be considered disputable, you might want to use a caveat such as ‘according to …’. Such care in distinguishing opinion from f act will help to establish trust in your readers. But if there are libel dangers, get legal advice on such statements.

At a local council meeting the reporter hears the water company representative, asked about the recent water shortages, say that there is no problem. In the reporter’s contact book, however, is a water engineer who has been helpful with leads in the past. He says that there are leakages and that more money needs to be spent on maintenance. The reporter is asked by the editor to check cuttings and do an investigative piece. It is agreed that the engineer will be described as ‘a reliable source’. The story develops into a campaign. After several investigative pieces over the course of a year culminating in a feature by a water engineer who contributes to business-to-business magazines, the funds are provided and the water supplies restored.

Make sure your notes make it clear where you’re quoting and where paraphrasing. Quotes in notes (with ‘paraph’ in brackets) can simply remind you to paraphrase when writing up and so avoid the risk of being accused of plagiarism. (It’s easy to copy material directly into your notes and forget they are the original words when writing up.) ‘Style’ in brackets after quotes can remind you to use the words in your piece to indicate the writer’s or speaker’s style.

You may have thoughts about the points you are noting. If so, put them under the notes in square brackets. Note the source at the end of each note, so that you can return to it later, if necessary, to check: author, title of book or article, publisher or title of publication, date, page number; or name of interviewee with date of interview; or event attended, with date.

Quote that significant statement when writing up even if it’s in the form of a phrase included in otherwise paraphrased material and your own commentary. For example, ‘Twenty years ago Paul Harrison wrote that crime rates were highest in the inner city, which was “Britain’s most dramatic and intractable social problem” and perhaps the same could be said today.’

Paraphrase facts that are repeated in various sources and introduce them by saying something like ‘Most experts/historians/footballers agree that …’ Chapter 10 shows how well-organized notes are developed into a well-organized feature.

Logging and ordering

If you’re going to interview several people for a news feature, you may be able to work out a good order to do them in, so that your understanding and your questions are good. After perhaps some reading for background you’ll probably, as we’ve seen, start with people most knowledgeable about the current situation, with overview; move on to people able to comment on specific detail; ending if necessary with summing up and if appropriate speculation about the future. When your interviews are done, you will think about different ways of ordering the material for interest and effect. Make sure your reporter’s notebook carries your name and phone number in case it gets lost.

Let’s take a fictitious example. In the county of Jaytonshire, the town of Rowdyborough is about to establish an alcohol control zone in the city centre in a month’s time. It will be a trial for six months. If it works, the scheme will be repeated in other towns in the county. Already the city of Peacewick in the neighbouring county of Beldonland, also visited by many tourists, has transformed its centre by creating a dry zone by means of a by-law.

You’re a feature writer for the Jaytonshire Gazette and you’ve been asked to write a feature of 900 words, provisional title ‘Will a dry zone work in Rowdyborough?’ The town suffers more from drunks and hooliganism than Peacewick did. You decide on an order of interviews and you will organize the results of your research so that the story can be clearly seen in summary. It’s a good idea to keep a separate logbook as well for all your phone calls. I’m assuming the telephone interviews listed are not too time-consuming and that you know exactly what questions you should ask. Here’s how it might look (F = face-to-face):

| Item | Source (dates would be given) | Data |

| 1 | Coverage in the Rowdyborough Gazette, press releases from the council |

Background: The Criminal Justice and Police Act 2001 and the Local Authorities (Alcohol Consumption in Designated Places) Regulations 2001 give local authorities the power to restrict anti-social drinking in designated places and to provide the police with the power to enforce this legislation. |

| 2 | (R) Council Report on Consultation with local residents and businesses |

140 responses, 137 in favour, two don’t knows and one in disagreement. Reference also made to noise pollution, street lighting, skateboards, mountain bikes and beggars |

| 3 | Email from R Councillor Joy Luckock, Community Safety Department |

‘We want to protect R’s rich heritage for everyone to enjoy. The alcohol control zone is just one measure we’re introducing to make R safer. We’re not killjoys. Publicity? Posters, handbills, street signs, warnings from clubs, pubs and shops.’ |

| 4 | Phone: Deputy Leader of R Council Norman Finch |

‘We’ve picked R for this pilot scheme because it’s a great attraction for tourists and we can learn from what happened in P. In the evenings people can be intimidated by the drunks.’ |

| 5 | Phone: Jaytonshire Police: Inspector Roy Bartlett |

‘We have talked to our colleagues in Beldonland and Sgt Michael Higgins of Peacewick will be helping us at R for a period.’ |

| 6 | Phone: (P) Sgt Higgins | ‘In the two years our scheme has been operating there have been only three arrests. People drinking in public are asked to move, and they know about the by-law and they move.’ |

| 7 | F: (R) Margaret Baker, National Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders (NACRO) |

‘The situation in P is not entirely satisfactory. There has been insufficient back-up from agencies like ours for people moved on. Sometimes the police could cooperate more with us. Some of the drinkers in town centres have recently been released from prison, some are alcoholics who badly need help and we lose sight of them. They take their problem somewhere else. You could talk to Shelter.’ |

| 8 | F: (R) Shelter: David McManus | ‘There are day and night shelters for the homeless and the scheme will work if people moved on are referred to us.’ |

This follows the facts-gathering order I suggested would be good. In the writing up you could lead in with some colour, set the scene: a typically noisy Rowdyborough centre in the evening (you would go and have a look). Perhaps you could note an incident that reveals the scale of the problem and the need for action. Or you might want to start with the quote from Mr McManus if it sums up your own viewpoint. And in your lead-in you’d probably introduce as a link the doubt that comes with the question of the title. The laws and the consultation report would have to come early but you’d have to get readers interested in the situation first.

Question creatively

However well you do your preliminary research, however clear you are about what you want to find out and about the shape of the final story, however well you prepare your questions, however interested you are in people, however good a listener you are, however good you are at keeping your interviewee from rambling away from the subject, and at juggling your notebook, pen, telephone receiver, tape recorder and whatever else you have to juggle, however good you are at organizing your notes, you’ve got to add some creativity. That involves understanding people, adapting your techniques to their personalities, knowing how to phrase a question in different ways to get the facts out of an introvert, an extrovert, a workaholic, an alcoholic, people with their own agendas very different from yours, people suspicious of your intentions, people with something to hide, and so on.

Creativity also involves, as all that implies, that you’re ready for the unpredictable. You’ll discover facts, whole stories sometimes, different from what you expected. You often have to adapt or change your prepared questions on the hoof to take account of those unexpected answers. At the same time, an interview for information isn’t like a conversation where you’re delighted by completely new vistas opening up to be explored. You’ve already got your vista and must not be deflected by facts, however interesting, that are irrelevant for your purpose.

This kind of creativity will improve by practice, and by studying good research interviews. The following is a list of tactics of a general kind.

• Prepare on the whole simple questions, open-ended, not requiring yes or no: use your who, what, when, where, why and how.

• Prepare some good specific questions, suggested by your knowledge of the interviewee and of the current situation. Generalities create a fog. You want specifics which make for clarity and readability. Ask for specifics in an appropriately polite and natural manner. To ‘were there communication problems within the company?’ you’re in danger of getting the answer ‘yes’. Engineer a polite sequence in a natural conversation. Something like: ‘I know that in 1998 you were unhappy about the lack of communication between departments and even within departments … Did you find that friendly relations were at a low ebb when you resigned? Was there any socialization after working hours? Have you kept in close touch with your ex-colleagues that remain on the magazine?’

• Ask for examples/anecdotes/quotes. A Detective Inspector tells you that very personal information about people has been obtained by talking to their neighbours. ‘Have you got important evidence this way? Can you give me an example – without mentioning any names of course?’

• Exploit revelations. (‘I wasn’t feeling myself at the time … but we won’t go into that.’) Avoid being totally occupied with keeping up with the note-taking. Follow up any unguarded remarks that promise a seam worth digging into, but emotions and opinions must be essential to the story if you’re going to follow them up. You’re not doing a profile.

• Collect some colour when relevant. A little usually is. The rowdy evening scene in Rowdyborough (with a description of the participants, unkempt beards perhaps and beer cans), was a suggested intro to that story. If legwork isn’t possible, you can collect the colour and perhaps one or two anecdotes and quotes from the people you talk to.

• Check some facts as you go. Get names of people and places you’re not sure of spelled out. Get anything you don’t understand repeated or explained, especially jargon.

• Get more information than you need. You’re much less likely to have holes in your story.

• Keep the person on track. Politely. Your interviewee may prefer to talk about something else. You’ve got the list of questions, you’re making the notes, you’re in charge, or you should be.

• Loosen the person’s reserve. When you get ‘I don’t like talking about it’ or ‘I’ve no patience with that kind of activity. Full stop’, just asking ‘Why do you say that?’ or ‘Why do you feel like that?’ can open the gate. You may be able to loosen the reserve by showing your genuine interest and concern. Instead of firing another question try reacting emotionally: the lack of a question can have a relaxing effect. For example, ‘I can understand why you may be reluctant …’ or ‘How wonderful that you can still have a positive attitude!’ or ‘Criminal! I’m not surprised you couldn’t put up with that.’ (I did say genuine: don’t overdo it.)

• Find time for a review at the end of the interview. Are there gaps in the story you can plug with another question. Is there something that doesn’t quite add up?

Questions not to ask

• How did you feel when your grandmother fell off a cliff?

• How did you feel when you were told you had won such a prestigious award?

• Were you ready for the amount of fame that suddenly enveloped you?

• Your last play was panned mercilessly by the critics. Don’t you think you should try another medium? Or is it too late in your career? Have you ever thought of giving up writing altogether?

• You’re obviously the most promising writer of your generation. Are you on a roll, or do all the accolades put too much pressure on you?

• You’ve been called the most beautiful bum in the world. Are interviewers always bringing that up, and if so is it beginning to irritate you a bit?

• You are well known for your large donations to charity. Do you try to keep them quiet or is it good for your career/business? (It may be a good question if drastically rephrased.)

• How are the share prices of your company going on the stock market at the moment? (You should already know how and have some idea of why.)

• Have you stopped beating your wife? Don’t ask any version of the famous trick question, encouraging an answer, whether yes or no, that implies he used to.

Use techniques of persuasion

The more difficult interviewees, especially those with much experience of being interviewed by journalists, present another kind of challenge. Even securing the interview in the first place may require much more obstinacy than is healthy. Secretaries and assistants will tell you he or she is at a meeting, is not in the office, will ring you back, will ask if you will ring back next week, and so on, which may sometimes be true, but are often ways of fobbing you off. Keep trying until your target realizes that cooperating will be easier than resistance.

PROs, information officers and press officers, in particular, start from different premises. The quid pro quo nature of the encounter is tacitly accepted. The publicists avoid giving information that may be compromising, the journalist tactfully avoids being used as a vehicle of publicity.

The publicist may give facts that put a product or service in a good light and omit several other facts that do not. Multiple check sources, as has been suggested, may be the answer to this ploy, but the journalist may be hamstrung by the deadline. Try giving the impression that you know those other facts but that you might make them out to be worse than they are.

Spokesmen of business organizations, like politicians, are highly skilled in giving you the information they have decided to give you, cunningly evading your questions while apparently answering them. Bringing them back on track may require firmness with ‘You have not answered my question’ or ‘Interesting, but that’s not exactly what I asked’.

When firmness is not enough

‘Are you keeping back information that the law says I can have?’

‘Do I have to tell my readers that you personally declined to give me this information? Won’t a “no comment” look bad for y our organization, make the situation look worse than it is? Make it look as if you’ve got something to hide?’

‘Do you refuse to let taxpayers (or ratepayers) know what you’re doing with their money?’

Such veiled threats are, however, the last resort. They can lose their bite anyway if you can’t determine exactly where accountability lies.

Go on the hunt for elusive figures

The insurance company’s director says he can’t give you the rise expected in the premium from next January. Try guessing too high.

‘About 25 per cent I’ve been told?’

‘That’s too high.’

‘15 per cent?’

(Pause.) ‘Perhaps a little more.’

‘If I said about 20 per cent I wouldn’t be far off?’

‘You can say what you like.’

That gets the director off the hook and you’ve got a good figure.

Produce an awkward silence

Produce an awkward silence. You ask an awkward question. You get an awkward, incomplete answer. You wait. Your interviewee will probably feel more uncomfortable than you and may start filling the silence with what you want.

Leave embarrassing questions that must be asked till later. Don’t start with ‘Funds gone missing! All the red-tops after you! I thought you wouldn’t want to talk to me right now!’

Look for signs of something to hide

You ask for an opinion about athletes taking illegal drugs to enhance their performance. Your athlete says he has never done so, and explains why he was once suspected of doing so. Guilty conscience? Or if you have strong evidence that a parent has punched a teacher, ask him why he did it and you might get an admittance rather than ask did he do it and get a denial.

When to get legal advice

If an interviewee asks you to keep a statement ‘off the record’, ask if you can use it without attribution. Explain why you feel it’s vital to your feature and would not be a problem. If you think publication is in the public interest, you may want to include the statement; if you think there’s a legal danger, alert the publication’s legal expert.

A case of bureaucratic stalling

You have embarked on a special feature on race relations for your local weekly, induced by a report published two months ago by the local branch of the National Union of Teachers. This indicated that black teenagers were victims of discrimination and failing to get jobs. The local careers service promised figures to give a clear picture and have failed to produce, despite several letters and phone calls. The NUT and the Council for Community Relations have also failed to get figures.

You try the Principal Careers Officer again. She says the Chief Education Officer ‘is not available for comment, but is working on it’. Later the careers service inform you that separate statistics are not kept but that ‘a special report on black teenagers is being written, although there is no deadline for it’.

The Chief Education Officer next tells you that the department has not had time to extract the figures. But the Council for Community Relations was told a different story, you discover. It was told that the officer had not approved the use of resources to collect the figures. The pressure groups’ scope for action is limited until they get the figures. Your deadline is approaching and it looks as if you won’t get the figures for the current feature. What you say in your article, though, may make them arrive more quickly. You will no doubt fight on, with others, against the bureaucratic ramparts, making your notes. There will be revelations in due course but for another special feature.

Elicit good quotes

Good quotes from the subject mean those that:

1 are needed to give authority

2 are interesting and illuminating for the reader

3 make interviewee’s opinions stand out

4 are given a fair interpretation.

1 Quotes can indicate that the subject has the knowledge or experience to give a statement authority, to deserve readers’ attention. Readers will trust that any facts quoted will be correct, for example. Well-known or easily checked facts, of course (the company’s turnover last year was £12 million), don’ t need quotes.

2 Interesting quotes will come out of who the subjects are, what they do in life, their personalities. Charm, quaintness or oddity rapidly wear thin on the printed page unless there’s also some insight into an interesting character. It’s up to the writer to awaken readers’ interest in the subject, to ask questions that stimulate interesting answers and to provide the context that will make the quotes not only interesting in themselves but relevant to the piece and illuminating.

You can build up interest in a subject before you start quoting. Looks after his widowed mother with Parkinson’s disease? Keeps a dozen snakes as pets? Believes she has psychic powers? You can incorporate an interesting factor within a quote: ‘I was summoned to the manager’s office,’ said Andre Baines, who had risen through the ranks meteorically in six months. ‘He told me I was dismissed.’

A long stretch of quote can be boring unless the reader is hooked by the speaker. The writer can help by breaking it up with paraphrasing, summarizing, changing the pace by continuing with the main narrative, and so on. More in Chapter 16.

3 Quoting can make it clear that a speaker’s words are what the speaker believes and that the view is not necessarily shared by the writer. For example: ‘The manager had referred to Mr Baines’s “personality defects” and “lack of commitment to the company”.’ Leaving out the quote marks would imply that you agreed with the verdict, and you would get into trouble with Mr Baines, if not the law.

4 You must make sure that you represent a speaker faithfully. People say things in anger, or with humour or irony that they would express quite differently if they were writing for publication. People who are not used to being interviewed may have little idea of the impression their words will make when they appear in print. They may need to be warned, ‘Do you really want me to print that?’ On the other hand, when speakers inadvertently reveal the truth, which doesn’t show them in a good light, and it’s the truth you’re after, and you’re asked ‘You’re not going to print that, are you?’ there has to be a compelling reason not to say yes.

Things are said during an interview that need to be put into the whole context of the interview if they are to be interpreted correctly. Since only you, the interviewer, knows all your subject has said, you must ask yourself whether what you have selected gives a fair impression. If Mr Baines makes one derogatory reference to the manager’s character (‘he was vindictive’), referring to a particular event, and three other references that are complimentary, you will be doing them both an injustice if all you select is the derogatory one without even giving its context.

The writer may need to turn interpreter when the speaker misuses the language. A malapropism may be used: ‘psychotherapy’ instead of ‘physiotherapy’, for example. Or a word used may be ambiguous in the context, such as ‘trendy’. Is it being used in a complimentary or in a derogatory sense? Such matters need to be cleared up in the course of the conversation. You don’t, however, correct the kind of grammatical errors or odd turns of phrase that reveal a distinctive way of speaking unless they would cause misunderstanding.

Choose the best method

Telephone, email, letter, questionnaire, face to face? You’re more likely to be using the results of a questionnaire (survey, poll) than organizing one yourself, so this is dealt with in the facts checking section. To repeat: if you interview fairly lengthily by phone or face to face, use both tape recorder and notes. Ask for names, technical terms, and so on, to be spelled out.

There are techniques common to all methods. Your loyalty is to the truth as far as you can ascertain it, not to anybody else’s agenda. You must be friendly but firm, professional and persuasive.

You might need more than one method of interviewing for facts. Before making your choice (or after having the choice made for you) consider the advantages and disadvantages of the chosen medium. However reluctant your interviewee, anticipate that you may want to make contact again at writing-up stage. You may want to clarify a point or two, and even ask one or two more of those vital, specific questions, so ask for the privilege. With good judgement you should have achieved enough rapport for that to be granted. You may need home phone and mobile numbers at that time: you may have a looming deadline.

When it’s not face to face, remember that the people you’re addressing cannot see the encouragement on your face. For email and the post put that encouragement (inspiration?, empathy?, friendliness?) into your words. On the telephone put it into your voice as well.

By telephone

This is best for brief interviews for facts and you can establish rapport with your voice. If you play it skilfully you will get unguarded moments. After a phoned interview, people worry that you’re going to misquote or misrepresent them. You should be able to reassure them either that you’ve taped it, and/or that you will read over before publication what you’re intending to quote.

By email

This is an advantage when you want your interviewee to be completely at ease, having time to prepare considered answers, and when that is exactly what you want. You will lack colour and intimacy that come with tone of voice. You can’t pursue the strategy of building on early answers to inform difficult questions left to the end. You display all your armoury at once. You may be able to follow up with further emails, but that’s not quite the same thing.

By post

This is often requested by academics and occasionally by writers when the interview is going to probe areas that need careful responses. If you have plenty of questions that go beyond mere facts, this method may be best. But it is normally reserved for a full-scale interview feature.

Face to face

The advantages have already been suggested: you get body language, tone of voice, surroundings. You can manipulate the proceedings, adapt your questions and their order and phraseology to the personality, create the scenario as you go, adapting to each answer. When you come to the end, and there’s still an important question you’ve failed to get answered, you can switch off the tape recorder or put away your notebook and even be accompanied to the lift, both of you quite relaxed, and you can rephrase that question and get a relaxed answer. Make a note of it later.

Let’s leave the rest of the psychology until Chapter 16.

Acknowledge your sources

As described, your notes should alert you to the sources you need to acknowledge. We’re now taking acknowledgement a stage further, to where you need to obtain the source’s permission to use quoted extracts, as well as to acknowledge.

Appendix 4 gives the Society of Authors’ Quick Guide to Copyright. Copyright under the current law expires 70 years after the author’s death. Before then, as a general rule you can quote an extract up to a short paragraph without permission as long as you acknowledge it.

But the current tendency is to charge for reproducing short extracts and publications vary in their demands.

Establish bonds with contacts

Two professionals have met with different agendas. You have to negotiate, mark out the boundaries, make compromises perhaps. You have to establish a rapport, with the future in mind, without making too many promises. You may be asked to explain, for example, how the subject covered will be treated, exactly how what was said will be used in the forthcoming feature. Even if you have some idea, it will be wise not to comment, and to say that the editor must be contacted on that question.

You may be asked to show your interviewee the script of your feature, however brief their contribution. Avoid this. Seeing their words in typescript makes some people regret the frankness and want to substitute platitudes. If the material is highly technical, however, or liable to be misunderstood, you may want to agree to sending a script for verification on condition that changes are made only for reasons of accuracy or to aid understanding. Sometimes reading a script over the phone, resulting in a few minor changes of emphasis, may satisfy both parties.

It’s a matter of trust. If you come across as vague or disorganized, you may find it hard to persuade anyone that sending a script for checking is not usual. If your interviewee comes across as hostile or suspicious, you will be reluctant to continue the association in any way.

A most regrettable situation, which should arise only rarely. You have worked at establishing a rapport because you may have to make contact again. Something may not be clear, or you may have left out an important question, or your editor comes up with one you hadn’t thought of. The name is in your contacts book and you may find it a useful contact for future articles.

VERIFICATION SKILLS

Find reliable sources, we have said, to avoid needing too much crosschecking. Let’s consider the verifying first of facts, then of figures.

Verifying the facts

Five facts you’ve discovered suggest that Mr A is alone responsible for some corrupt procedure. If you had more time you might discover five more facts from other sources that show the blame should be shared between Mr A and Mr B. With even more time you might discover that Mr C should share the blame too. But your deadline is tomorrow so you talk to your editor. If Mr B and Mr C live in Paris, will the editor pay for travel/hotel/meals and for your time if you’re staff? Will phone calls suffice? If it’s decided that the story isn’t worth the expenses and risks being libellous if based on current information you might be paid a kill fee.

How many facts make the truth?

A news story can run and run in the papers. New evidence arrives daily. The news writer cannot preface too many statements with ‘as far as we know’. If you’re writing a feature based on a running news story you can describe evidence as ‘circumstantial’ to indicate that there are a number of facts that appear to arrive at a certain conclusion although one of the facts by itself would not be proof. If the conclusion seems less certain you can use the term ‘anecdotal’.

It’s natural to make extensive use of media sources. Keep in mind that they in turn often depend heavily on previous reports and articles. Anyone who has spent an hour or two in a newspaper cuttings library will testify to the danger therein. Going back over the life of Elvis Presley, say, or the United Nations’ use of force, you are struck by the way an error can be made in an issue of one newspaper and be repeated by that paper and other papers and magazines for months or years. The original may have been a printer’s error.

Some of the misuse or misinterpretation of facts perpetrated by the media is careless reporting. For example, the terms used to refer to refugees are confused. There’s a tendency at the time of writing for much of the media, and much of the population, to lump together refugees, economic migrants and asylum seekers with illegal immigrants. Refugees have a genuine fear of persecution in the countries they came from. Economic migrants have been encouraged to come here to fill skill shortages. Asylum seekers are awaiting a Home Office decision to qualify as a refugee. Illegal immigrants are not asylum seekers: they are here without official authorization.

Verifying the figures

Paul Donovan in the Press Gazette of 26 July 2002 (‘Siege mentality’) gave some figures collected by MORI Social Research Institute in a poll for Amnesty International, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) and other agencies. How many of the world’s refugees and asylum seekers ended up in the UK? Most people thought between 10 and 19 per cent. The second most popular guess was between 20 and 29 per cent. The actual figure was 1.98 per cent.

The backing of those agencies makes us feel that we can trust those figures. There are, however, many weaknesses in the way questionnaires are set up and used that can make the results of the polls of little use. How big was the sample, how representative, how many failed to answer, what was the effect of these considerations on the results? – these well-known checks are still often ignored. If you’re so bold as to want to use a questionnaire in your research, check the Bibliography for a guide to how to use them.

Don’t miss Darrell Huff’s classic How To Lie With Statistics, which reveals the flaws to look for in figure crunching. That ‘average’ we hear so much about: is it a mean average, a median or a mode? Quite different matters, and sometimes the distinction is crucial. Be wary, similarly, of IQs, the charts and graphs sometimes used by companies to give misleadingly favourable pictures of their progress, and percentages. Percentages of what, exactly?

ASSIGNMENTS

1 Write a 900-word feature based on the notes for ‘Will a dry zone work in Rowdyborough?’ for The Jaytonshire Gazette.

2 Wind Farms – The Energy of the Future?

Wind Farms – Who Wants Them?

Wind Farms – A Foolhardy Policy?

Research and write a 1200-word feature on wind farms targeted on a national paper or consumer magazine. One of the above titles may reflect your point of view, but you may prefer to choose your own title. The current situation at your time of writing will determine your approach and your facts and figures. At the time of writing Britain is running out of gas, which accounts for 40 per cent of the electricity produced. There are predictions of increasing power cuts ahead. The Government has proposed building giant wind farms in three places off the coast of Britain. The electricity industry considers they will not solve the problem.

Possible sources

Scottish Power

Manweb

National Windpower Ltd

Wind Development UK

Centre for Alternative Technology

Friends of the Earth

Suggested group work

After some preliminary study of the topic, divide the group into For and Against teams. Each team could divide up research and drafting work, with a spokesperson to present the team’s case in debate. The debate can then be open to the floor. Finally each member of the group can write the feature, without any obligation to keep to the viewpoint of their team.

3 Write a feature of 1200 words entitled either ‘We Need Identity Cards’ or ‘We Don’t Need Identity Cards’ for a selected target. Make sure you give a clear description of the bases for such discussion.

Research will include, for example, explaining the Data Protection Act. In particular, what information that is held by organizations about yourself have you the right to discover? What information does the Act forbid you to discover?

Authors recommended: David Randall (The Universal Journalist, Chapter 10); books by David Northmore and John Pilger on investigative reporting.