3 From idea to publication

‘Why are you here? Why aren’t you sitting at home writing?’ John Steinbeck said. The author of Of Mice and Men and The Grapes of Wrath and Nobel Prize winner was addressing his writing class at their first meeting.

He had started with the most important bit of advice he had to give. You have to develop your writing skills by doing it. All the rest – the lectures, the books like this one – is advice that you must adapt and apply to your particular purposes, to what you write, and the important thing is to write regularly. You don’t become a good cook by reading cookbooks.

This chapter covers the whole process of producing a feature from idea to the piece on the published page. The following chapters expand on the different tasks.

THE FEATURE DEFINED

First, we’d better ask: what exactly is a feature? The best approach, I think, is to compare and contrast it with a news report.

Skills that are common to the production of news reports and features are the need to appeal to a wide audience and to be readable, in the sense of purveying accurate information in an interesting way as well as following correct usage, including grammar. Other forms of writing, for example the essay, of the pupil at school or the undergraduate, the business report and many other kinds of writing, must testify to knowledge of the subject tackled and must communicate clearly. But they don’t have to appeal to a wide audience and the journalistic kind of readability is not a high priority. University graduates often find it difficult at first to leave an academic style and frame of mind behind.

Those common skills for reporting and feature writing are employed to satisfy a particular readership. That may be vast and varied, as for the popular national newspapers, or it may be narrowly specialized, as for professional journals. The writers on the staff of a publication soon get to know their readers and how to address them. They get to know their age group, educational level, lifestyles, and so on. Freelance writers have to make a special effort to market-study a publication they aim to write for, in the ways described in Chapter 5.

But we have to start with reporting and then see how feature writing builds from that basic skill: examine what features add to news content and the different structures they employ.

Content

Still the neatest way to illustrate what’s news and what isn’t is: ‘man bites dog’ is, ‘dog bites man’ isn’t. News is about recent events, previously unknown, says the dictionary. Expanding somewhat, news has the qualities of conflict, human interest, importance, prominence, proximity, timeliness and unusualness, in varying degrees. News may be merely of public interest but it may also be, more importantly, in the public interest – of public concern.

Ideally, a news story is objective. The facts are ascertained by the reporter’s five questions (Who, What, When, Where and Why) plus How. That formula is a valuable guide to determining what any piece of writing is about. You ask whichever of the questions will fit, and sometimes they all fit.

News is often classified as either ‘hard’ or ‘soft’. Hard news is about something important and sticks to the facts, as far as possible. Ideally, it is objective. Soft news is written round entertainment, personalities and human interest stories, and takes up most of the space in some of the national tabloids. You still need those questions.

A feature, says the dictionary, means something distinctive, or regular. Where does that ‘regular’ come in? Well, features on particular subjects tend to have regular places in a publication, with familiar and sometimes renowned bylines.

‘Distinctive’? In journalism a feature, like a news story, aims to inform, but it may also narrate, describe, explain, persuade or entertain, and sometimes all five. It may aim to inspire or stimulate the reader to think or provoke to action. It has distinctive characteristics that add something to the facts.

Many features in newspapers and weekly news magazines fill in the background to the news and help us to put the news into perspective. They explain why events happened and may speculate on the consequences. Even features in the lifestyle sections of newspapers and in general interest magazines that aren’t directly related to the news normally have a topical peg of some kind. For example, pieces on gardening, cooking, DIY and travel will get some topicality out of the seasons; other pieces will latch on to an anniversary, after looking up a Dictionary of Dates. But of course everybody’s doing that, so do it sparingly and cleverly. Please don’t even mention Christmas.

There is usually more space for a feature and therefore more scope for subjectivity, imaginative ways of gaining information, or for originality of expression. But features must be based on accurate reporting of the facts.

Subjectivity cannot be completely restrained, however, even in what sets out to be straightforward relaying of the facts. It’s hard to be objective about the horrors of war. Robert Fisk, reporting ‘this filthy war’ in Afghanistan for The Independent, made it clear where his sympathies lay, and after being badly beaten up at an Afghan refugee camp in Pakistan declared that he would have behaved like his attackers if he had been an Afghan refugee.

Such ‘point-of-view reporting’ has increased since the broadcast media became the main purveyors of the news as it breaks. When the main news is televised at night the morning paper has to try to add something to the news and comment creeps in. Middlebrow papers have features reflecting on the social issues underlying TV’s sitcoms. Popular papers give much space to the private lives of the stars of TV soaps. Thus the distinctions between hard and soft news and between news stories and features have become blurred.

The feature writer should make it as clear as possible where facts end and point of view begins. But it’s not a simple matter. Subjectivity is in every breath you take and is behind every selection you make of the facts.

Structure

News structure in newspapers is often an inverted pyramid shape, the most important point coming first, explained by answering those six questions (or as many of them as are relevant). Readers short of time can content themselves with the first paragraph. As the news comes in items have to be cut to make room, and the structure described makes it easy for subeditors to cut from the bottom. This doesn’t always work because breaking news may require changes and the subeditor may have some rewriting to do.

The danger in relying too much on the inverted pyramid shape is that the reporter may produce a first paragraph or two that is overloaded with detail. Something like:

Joe Quinn, who comes from Cork, is preparing to complete a sponsored walk on July 25, setting off at 10.30 am from Tooting Bec in London with the aim of raising funds for The Greater Chernobyl Cause (GCC), which will go to the Ayagus orphanage in the town of Seipalatinsk, Kazakhstan, children having regularly been abandoned there since the atom bomb testing in the region in 1949.

The side-effects remain today and children are still being born with multiple deformities.

That first par certainly gives you who, what, when, where, why and how, but it should start with the what, the story in a nutshell, and bring in the details later. Something like:

A London-based Irishman is walking to raise funds for the severely deformed children in an orphanage in Kazakhstan.

The rest should be covered in shorter sentences, avoiding subordinate clauses (‘who comes from … which will go to…’) and participial phrases (‘having regularly been abandoned’).

The term news story reminds us that there must be an angle to a report: the facts must be selected and ordered to make the point concisely and readably.

While the reporter is told to ‘kiss’ (keep it short and simple), the feature writer is allowed more scope for individuality in structure as well as content, as long as the prescribed length is adhered to, and words are not wasted. In other words a feature should need only light subbing, and sometimes the writer is contacted to do any necessary subbing or to agree to a cut. Features, in their greater complexity, take many different shapes. A common shape is the pyramid the right way up, with a conclusion of some sort at the end.

A word here about the basic differences between the newspaper feature and the magazine article. The former is generally urgent in tone with information being used to work out viewpoints or conclusions. The latter is more inclined to spread itself, giving more attention to colour and readability; it may be more inclined to raise questions or doubts and to leave you to come to your own conclusions.

THE STAGES IN PRODUCTION

Which is the best route from idea to the feature on the published page? There will be several shortcuts once you’ve got editors ringing you to ask for a thousand words next Monday. If you have, you can skip this chapter. If you haven’t, let’s assume you want to get published a feature of, say, 600 to 800 words. How would you go about it?

There are features of this length you can do out of the top of your head: personal experience, humorous columns, a day at the races. Jot down a few points, indicate the best order for them and get on with it is the norm. Or do a draft and polish it up for a final version. Even then you might find it better to work from a brief outline: provisional title, intro, body, conclusion, indicating a few linking devices.

But few good features come straight out of your head, even modest-length ones. So let’s assume that you’ll have to do some information gathering and make a few notes before planning and writing up. On the way you’ll have to deal with editors, and there may be ways of following up. Here are the stages you might want or need to go through:

• From idea to market

• Getting commissioned

• Gathering information

• Simple outlining

• Writing up methods

• Vetting and rewriting

• Submission

• Spin-offs.

From idea to market

A subject for a feature is not enough: you need an idea. An effective title can make it clear how good an idea it is. ‘Giving doctor a taste of his own medicine’, a Guardian article, is a study of how barriers to communication between doctors are being broken down. ‘The education of doctors’would have indicated the general subject only.

An idea is a specific angle or approach to a subject. Ideas for features tend to deal with a specific problem, tension, drama, struggle, conflict, question, doubt or anxiety. The subject ‘Police in Britain Today’may become the idea ‘The Police: Are They Racist?’ Editors consider not only whether their readers would like the idea, or want it, but whether they need it.

Ideas may come at any time – on a bus, in a pub or restaurant, while watching TV. This means that you should carry a notebook and pen wherever you go (or a dictaphone). Have your notebooks paced at strategic points in your home – in the bathroom, kitchen, sitting room, on your desk, on your bedside table. Surf the net for ideas, via newsletters and discussion groups. As a staff feature writer ideas will come out of the news and features currently of interest to the readers of the publication you work for. Many of them may be suggested by your editor. As a freelance you have to be constantly producing ideas and pitching them.

Sometimes the idea comes to you first. You work out what the likely market is, and then narrow it down to a target publication or two. Sometimes your ideas may be suggested in the course of your market-study of likely targets. Whichever order they come in, you have to attune your ideas carefully to target publications. You will be reshaping some of the rejected ideas for other targets.

At an early stage in a writing career, depending on how much choice you have in the matter, it’s best to concentrate on subjects that you know something about so that you don’t get bogged down in research that slows down your rate of production. But keep in mind that what journalists can find out is more important than what they know. It is specialists that are in greater demand, so develop a few specialisms as you go.

Carry out basic market study by consulting the marketing guide books mentioned in Chapter 2, but that is no substitute for studying several issues of any target publication. As well as recording your dealings with publications (see page 12), file pages out of newspapers and magazines that indicate their policies and formulas – for example, letters pages, editorials and the contents pages of magazines. Newspapers and magazines can take up a lot of space and hoarding them indiscriminately in the hope that this constitutes market study can be counter-productive. It’s also a good idea to file pages (photocopy newspaper pages) that you find good models of different kinds of articles, good models of writing techniques, especially those that deal with your interests. Make a few notes in the margins. Sample likely publications online, including ezines – but note how much, if anything, they pay.

From market to idea

The above implies a move from idea to market and of course it’s often the other way round. Ideas suggest themselves while you’re looking through publications.

You find a woman’s monthly magazine interesting so you take a closer look, by studying the past six months’ issues or more. Much can be learned from the Contents page. You note which features are contributed by staff – you look for the regular columns and the pieces that are set up by the magazine for the staff writers.

The pieces by freelances, you note, include a fair number of interviews, thickly quoted ones. Many of the interviewees are women with unusual jobs. The interviews run between 800 and 1400 words. It so happens that you’ve just read a news story in your local paper about a woman who built up a mail-order business from home after being struck down by multiple sclerosis. You work out a way of developing this story for She, by doing some research into the disease and by finding out what help is available for the disabled to work in this way.

So, in whichever order you found them, you have an idea and a target publication. Where do you go from here?

Getting commissioned

You will have done just enough preliminary research into that disease before you pitch your idea to She. A main selling point will be that you can indicate that you have an interesting angle on it for those readers. You can’t afford to spend much time on research without a commission behind you. As you progress in a particular field, your commissions will require you to update information-filled files rather than start from scratch.

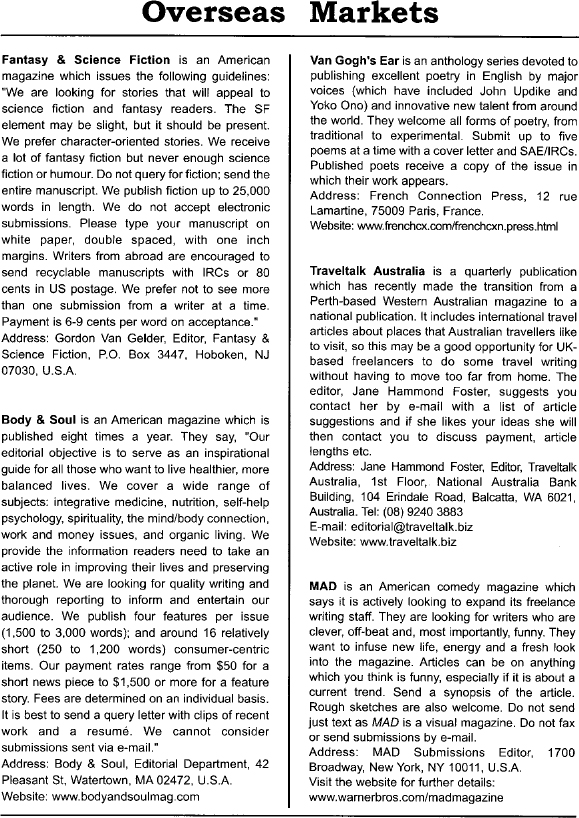

Figures 3.1 and 3.2 show sample pages from the Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook and Macmillan’s Writers’ Handbook. These are basic guidelines on how to get commissioned. The American Writer’s Market gives much more detail and is accessible online. You have to be careful to update the information by studying current and recent issues of the publications. Many magazines provide up-to-date guidelines online. Some magazines (again, more notably American ones) will supply, automatically on commission or in response to a request, more detailed guidelines, which may include:

Figure 3.1

Page from Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook 2005. © A. & C. Black, London, 2004

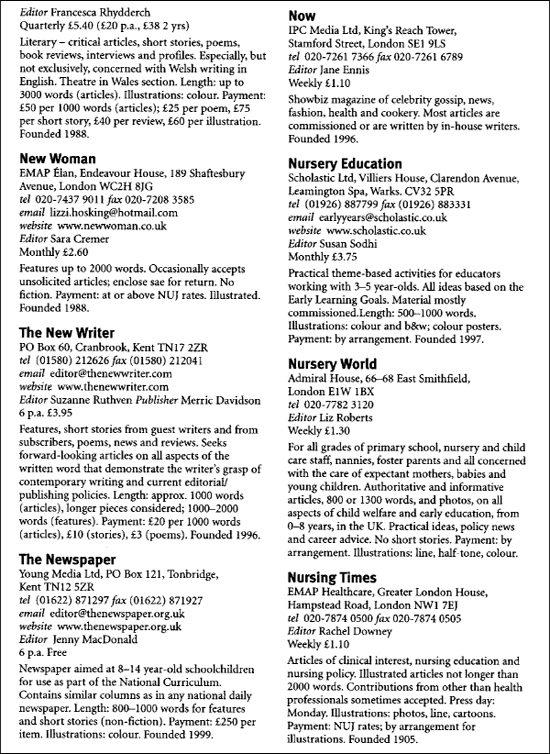

Figure 3.2

Page from The Writer’s Handbook 2005. © Macmillan Publishers Ltd., 2004, ed. Barry Turner

• How to pitch: by telephone, fax, email, letter.

• How detailed the pitch should be: whether they want a summary, a brief outline, a detailed outline.

• What personal details are required: a c.v., a brief summary of career outlining qualifications for tackling the idea proposed?

• What evidence of writing skill is required: by fax, by email (where they may be linked to your website), cuttings by post, or bring your portfolio to an interview?

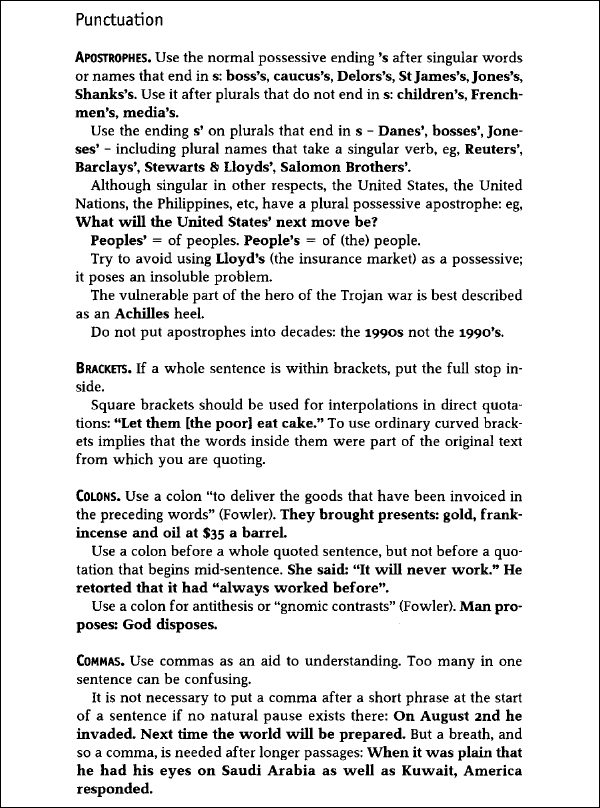

• The publication’s house style, the forms of words and phrases that a particular publication insists on. It may refer to The Times Style Book or The Economist Style Guide (Figure 3.3) but may add some special preferences (see below).

• Details of the publication’s readership, policy/philosophy, the formulas they want their features to adhere to, lengths and treatments required for particular subjects, the cooperation with subeditors required, and so on. A good example of this is the booklet Writing for Reader’s Digest which you can buy (see page 403).

• How to submit: for example, if by email attachment, should it be in .rtf (rich text format)?

Gathering information

At this stage let’s survey some sources of information and the techniques for using them on a fairly basic level.

There are four main sources for getting (and updating) information: from your own knowledge and experience; by legwork; by printed sources; and by interviews and conversations.

Participators in an event are first-hand sources. These include your own observation and experience, and interviews or surveys carried out at an event at the time. Second-hand sources include interviews with eyewitnesses and opinion surveys taken after the event when the recall may be less accurate; official sources such as PROs of companies, spokesmen for institutions and their publications and publicity materials; experts’ views; and all the other printed sources.

Figure 3.3

Page from The Economist Style Guide, Eighth Edition. Hamish Hamilton/The Economist Books Ltd., 1993 (first published as The Economist Pocket Style Book by The Economist Publications Ltd., 1986)

Personal experience

When you can bring some personal experience into your knowledge of a subject it’s unique and can be valuable. It will often be unconsciously employed. You may be able to write an occasional article almost entirely based on personal experience. How you faced extreme danger, or conquered anorexia, or established a club to keep disaffected youths off the streets, or started a new career as a freelance journalist in middle age should provide good bases for features.

To repeat, though, recognize that it’s what you find out that’s interesting rather than what you know. Work out how your subject is illuminated by having other experience, from other sources, used as a commentary on your own.

Legwork

You go somewhere and find out for yourself: that is the basic legwork activity of the journalist. You visit a fire, a factory, a mental hospital, a prison, a café, a pub or a government department, and you make notes on what you see and hear there. You’ll take a notebook and perhaps a tape recorder as well.

Printed sources

Appendix 5 lists some organizations with materials and facilities available for researching journalists. It’s worthwhile putting yourself on the mailing list of organizations, including companies in business, that are concerned with your specialisms or interests.

Time allowing, get informed on a subject from:

• Your cuttings. Replace your cuttings with information that updates them. Have a regular clear-out of old cuttings, keep your files manageable and don’t cast your net too wide.

• The library: books, newspapers, magazines.

• The library: electronic databases.

• Handouts, brochures and other materials from business organizations and voluntary associations.

• Scripts or back-up information from broadcasting organizations.

• The Internet.

Find the time to read enough to be able to select information that is significant and striking, to argue well, and to avoid leaving the reader with the feeling there’s a gap or that your treatment is superficial.

Readers new to researching techniques will find Kenneth Whittaker’s Using a Library (Andre Deutsche) and Ann Hoffmann’s Research for Writers (A. & C. Black) useful. A good encyclopedia in book or CD form can get you started into a subject and the entries provide brief bibliographies.

Find out from the indexes to publications which articles relevant to your subject have been published recently. The British Humanities Index (BHI) covers the broadsheet national papers and a selection of magazines. The broadsheets and several magazines produce their own indexes. Once you have noted published features you can access some of them on CD-ROM or microfilm and print them out. Some publications, however, have replaced these facilities by giving access to material online and some of this you have to pay for. Access Amazon online for titles of books on your subject.

Organization indexes such as the Directory of British Associations (DBA) list pressure groups of all kinds that will provide you with literature. Put yourself on the mailing list of organizations in whose activities you are interested and which are potential sources of material. PR companies, PROs and press contacts are listed in Hollis Press and Public Relations Annual.

Interviews and conversations

Even for the briefest interview during legwork or the five-minute phone call, prepare your questions carefully (ones that elicit useful answers: see Chapter 8). When researching a feature you might find good case study material in Internet chatlines. Talk to anybody who might have an interesting contribution to make, online or anywhere.

The oldest idea can be given fresh impetus by a well selected interviewee. That may be an acknowledged expert who has been difficult to corner, or an unusual choice who has a revelation to share.

Reference books for names you might need to interview include DBA; Who’s Who; the various extensions of Who’s Who (Who’s Who in the Theatre, etc.); The Central Office of Information’s directory of press and PROs in government departments and public corporations; film and TV annuals, Spotlight for agents of showbiz/film/theatre celebrities; Willing’s Press Guide, whose back pages list hundreds of specialized magazines; Keesing’s Record of World Events; and The Statesman’s Yearbook.

Give authoritative sources for facts and figures especially where they might be queried. If in doubt, say ‘according to’ or ‘allegedly’. Editors appreciate a separate list of key sources attached to an article in case there is checking/updating to be done in the office. But keep your confidential sources to yourself.

For picture research see Chapter 14.

Note-taking basics

Some notes may be taken on the move, in your reporter’s hard-backed notebook, and that may suffice for many features.

The NCTJ and other training organizations require journalism students to gain a shorthand qualification, for lack of accurate notes of an interview can lose libel cases. Transcripts of a taped interview and the tape itself should be kept for at least a year after publication of the piece in case an interviewee claims misrepresentation. For an interview of any length take notes as well as tape recording. Record what the number indicator says at key points, for example, or note where you feel you’ve got an incomplete answer that you might like to follow up later.

If you have not learned shorthand, work out some system. Journalists use Teeline, easy to learn from a book and/or evening classes, and more convenient than the more elaborate traditional systems. If you need to increase your note-taking speed, practise at lectures, meetings, or from radio talks.

You may have thoughts as you go about the points you’re noting. If so, put them under the notes in square brackets. Note the source at the end of each note thus glossed so that you can return to it later for checking. Compile a list of sources with full details so that you can easily locate them. Details might include authors, titles of books or articles, publishers or titles of publications with dates published, page numbers, names of interviewees with dates of interviews, events attended with dates. Editors might want your list of sources in case checking in-house is needed at the time of publication.

For complex tasks resulting in long features (say 3000 words or more) you may find it difficult to put those notebook notes in order, and you may also have a pile of original or photocopied source materials. Try transferring notes regularly to A4 sheets or to 6 in. × 4 in. cards, written on one side only so that you can shuffle them into the order required. Then do a logical outline like the one on pages 165–6, indicating where your various materials will slot in. There are computer programs that can help with this kind of organizing.

In your own words

Paraphrase when making notes so that you do not repeat other writers’ words and risk being accused of plagiarism. Do a complete job of this immediately. Put quotation marks round significant statements that you may want to reword later or use as quotes because the point is being expertly expressed, or because you want to show that the manner of expressing it is revealing of the writer.

Noting selectively

Don’t make too many notes. Read and digest background material, then select only those points that are central to your purpose. Over-researching, as already suggested, encourages procrastination – the feeling that you don’t know enough and must examine further.

Checking the facts

Facts and figures should be double-checked before submission of the final version. If you’ve extracted some figures from a newspaper report, for example, you should check what you’ve said against that report, and then check against the original source, if known – the government department or local authority or statistical publication or whatever. Check also doubtful spellings of names.

When figures don’t look quite right, a check against the original source may reveal that the figures themselves are correct, but that other facts or figures that were needed to put them into context are lacking. For example, we often learn that the figures for certain crimes are increasing. But does this mean that the crime is being committed more often or that more people are reporting it, or that police activity and success in bringing offenders to account are increasing?

Simple outlining

As a child (and sometimes much later) what you had to say all spilled out, along with several other things. ‘Yes dear, but what do you want to say exactly?’ you were asked. Eventually, with luck, you learned that to make clear what your main point is and what backs it up you must put what you have to say in order.

We do it unconsciously in our heads all the time. One way of describing this order is: ‘Hey! You! See! So!’ We can rely on this ability for short features and it’s not a bad basic formula. Let’s take a closer look:

• Hey! You! – grab your readers’ attention and show why they should be interested (intro, teaser, hook, beginning). ‘You’ turns into ‘we’ when a general argument is being pursued.

• See! – this is what I have to say (body, middle).

• So! (conclusion, summary, clincher, ending).

A feature in the Western Morning News supporting organic farming begins by telling readers that ‘we humans are a part of the natural life cycle of the planet’. The body gives evidence of health benefits from organic foods and relates conversations with people in shops and market stalls selling organic, and customers buying it. The conclusion is that we need a return to traditional farming methods containing ‘a high percentage of organic farming’. It would be ‘a huge step forward for the human race and our wellbeing’.

You’ll have your own ways of bringing about a good structure. You may prefer to work towards it in drafts, improving the shape each time, although most journalists tend to do all their tinkering or tweaking on the computer as they go. You may prefer to work it all out before you start with an elaborate outline that has the feature almost written before you start. Or you may like to saturate yourself in your material, make a substantial outline, put it aside, plunge into the writing and check with the outline when you come to the end. Does the outline suggest that there’s a better structure or does what you’ve written improve on it? Does the outline reveal that you’ve left important points out?

Whichever, there has to be a sense of freedom somewhere in the act of writing up, so that your imagination, where it is needed, can flourish, fresh ideas can be generated, and serendipity can happen. Too rigid or too elaborate outlines can be repressive. So be prepared to reject or redo an outline that doesn’t work well and start again.

Among the simplest formulas is the list. A 500- to 600-word piece on a Science Museum or the attractions of a city for a travel/holiday page works perfectly as a list of selected attractions to appeal to the readership. A brief hello at the start and goodbye at the finish will serve as intro and conclusion. Travel pieces at greater length, of the service kind, can have the same approach: for example, places to visit, places to avoid; or things to see, things to do; or day life, night life; or combinations.

You can use a simple formula for ordering a short or simple feature. Note the different points or aspects you have to cover. Then number them, say 1 to 4, according to how interesting or important they are. You may find 1, 4, 3, 2 the best formula, or if you have a great ending 2, 4, 3, 1. A longer article might work with 1, 6, 3, 4, 5, 2. Making a circle can produce a satisfying pattern. The conclusion echoes the intro, like a snake swallowing its tail.

Writing up methods

As mentioned computers have made rewriting as you go easier, however badly change is required: tweaking, tinkering, editing, rewriting are terms that suggest from little to much effort. The process of rewriting and reordering is made so easy. On the other hand that facility brings the danger that you may tinker too much and, especially if it’s a longish piece, that you might lose sight of the whole. It’s wise anyway, when you get to the end of a piece, to make a printout or two of the whole to edit. Keep earlier versions so that if you decide against certain changes you can easily reverse them. If at the editing stage you find a faulty structure, cutting the pars out and reordering them may work well. Paste or staple them on to sheets in the order wanted before rewriting.

Others have to get the intro right before they can get going. They write and rewrite it over and over again until they’re completely satisfied. They then find that the rest of the article comes easily. Others find that if they get hung up on the intro it slows them down badly. They find that for them it’s best to put something down to start so that they get going into the middle, and that the intro will come when they get to the end.

You may find that some of your best writing is done in overdrive. You’re full of your subject, passion is driving you on, the unconscious is let off the rein and you allow the sentences to flow. Collect from the shores of your consciousness like a river picking up debris as it runs. When the flow has subsided, remove any rubbish and put things in order. Some of the ideas yielded by the unconscious may be so valuable that you will revise your outline to include them.

Vetting and rewriting

Your way of revising on paper or on screen will depend on the way you put your draft together in the first place. If you tend to work from a detailed plan you may find the piece well structured but too predictable: you may need to inject surprises – in the content or in the language. If you tend to write now, worry later, you may find too many surprises and a lack of clarity and structure. Assume you share the faults of both writers when considering drafts.

Editors say about a feature they like that ‘it reads short’, and about a feature they don’t that ‘it reads long’. Articles with the faults described above read long. Even if they’re only 600 words they can be boring or wordily confusing. An article of 2000 words can read short, as if it were 600. A readable piece holds the attention throughout. Readability is achieved essentially by:

Content:

• making it interesting (entertaining, thought-provoking, etc.) for the target readership

• making it accurate and convincing (check facts and figures again in case errors were made in the writing up).

Structure:

• linking clearly (see Figure 11.1 for an example).

Language:

• making it as simple and direct as possible

• creating pace

• supplying excitement, passion, inspiration, etc.

Before your final version, put the latest draft of your article aside for an hour or two, or a day or two if you have the time. It will then be easier to read it with the eyes of an editor, freshly and objectively. Read it more than once, concentrating on particular aspects: first for content, second for structure and then again to look closely at the language.

Checklist

1 Is the overall purpose and audience clear? (Why did you write the piece? What did you hope to achieve by it? Was it effectively communicated to the readers you had in mind?)

2 Is the content adequate for the purpose? Is it significant enough? Was some information inaccessible? Did you manage to replace it?

3 Is the idea clear and compelling? Have you said exactly what you wanted to say?

4 Does the form (structure and language) match the idea and the content? Does it pass the readability test for interest, directness, pace and linkage?

For those who like code words you have PACIFIC.

Submission

When commissioned you will be told how to submit or given alternatives: by post, as email (attachment on disk?). Send two scripts (‘hard copies’) with a disk. Give a daily paper two weeks to consider your work, a weekly about six weeks, and a monthly about three months before sending a reminder to the editor, and have a list of other targets prepared so that rejected work is immediately sent out again (adapting or rewriting as necessary).

As a freelance, when work has been sent off it is advisable to start something new immediately: the best consolation for rejection is new work progressing well.

Following house style

As part of your market study of a publication you note its house style, the particular forms and usages preferred. If you receive writer’s guidelines from a publication you may be given the advice that in general The Times Stylebook or The Economist Style Guide is followed, plus a list of such preferences as ‘-ise’ rather than ‘-ize’, the forms of dates used and the way military ranks are printed.

Spin-offs

Clearly it helps if you can decide on possibilities at as early a stage as possible. When you open a file for a feature idea immediately note any spin-off potential. Ideas for spin-offs may come at any stage of the feature production. You might consider:

• multiple submissions, using a syndication agency perhaps

• multi-purposing from the start

• reshaping for different targets

• a script for radio or TV

• a book.

Multiple submissions

If your feature has a fairly timeless theme, you may want to send it out to one publication at a time rather than to several. You want to avoid two publications publishing, or wanting to publish, your feature at the same time (if this happens they may not be keen to use your services in the future). If you can be patient and decisions don’t take too long, and if you’re reasonably successful in getting features printed, sending out to one at a time is the best policy.

Point out that an early decision is needed, because if it’s not wanted you will want to try another target. Another advantage of one-at-a-time is that if rejected there’s an opportunity to rewrite the piece before sending it on.

On the other hand, if you have a piece that needs an early publication date because of a topical peg, you may want to send it out to several publications at the same time. Some feature editors may take months to decide on submissions. Play it by ear, find out how different editors react, establish relationships with editors that allow you to discuss this question of timing candidly.

Multi-purposing from the start

Most obviously a feature must be multi-purposing in the sense that it must both inform and entertain. It may serve other purposes, such as move the reader emotionally, persuade, amuse. As has also been pointed out, a feature has to engage with a large audience. That probably means both sexes and certainly a wide range of age groups, educational levels, interests, and so on.

Syndication

But multi-purposing can be taken much further. Written in a certain way the same feature can be syndicated all over a country, and worldwide.

You can do it on your own: offer the same feature to local newspapers, including freesheets, all over the country. Specify release time and date and indicate that you have not offered to other newspaper groups in the same circulation area. Each publication pays a small fee because of the restricted rights.

A syndication agency is worth considering. A regular feature used by many targets can bring substantial rewards, but you’re likely to need a syndication agency (see the Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook). But domestic syndication is more easily achieved in large countries, such as the United States, Canada and Australia, where there are many regional papers. Notable examples are the humorous columns of the Americans Art Buchwald (the Washington Post) and Russell Baker (the New York Times), who syndicate extensively in the USA and abroad.

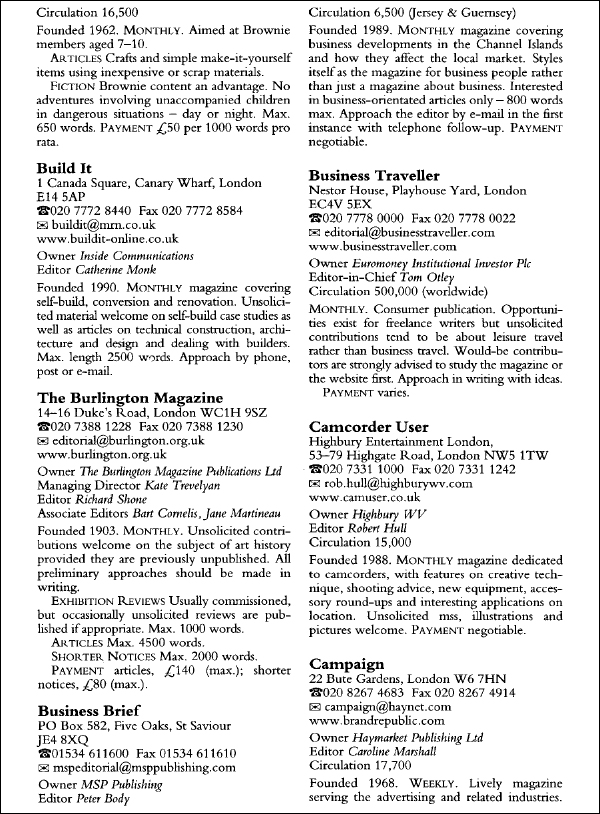

In a small country such as the UK, writers tend to look for overseas syndication possibilities. Freelance Market News is aimed at the beginner (Figure 3.4 shows a sample page). More in Chapter 20.

Reshaping for different targets

When the publications you want to reach with your subjects are quite different reshaping may be needed. Suppose one of your subjects is mentally handicapped. You have done a fair amount of research and have plenty of notes and cuttings on file (you may already have published an article or two). The subject for various reasons gets into the news so you decide to devote a few features to it. First you can divide your subject by listing various ideas suggested by your materials. Then you can consider the marketing.

Figure 3.4

Looking abroad: a page from Freelance Market News, Vol. 11, No. 9, April 2005 (The Association of Freelance Writers). With kind permission of Freelance Market News

You might interest your local paper in a story about problems of abuse in a local home. You might then use some of this in a piece for a national paper that shows how the wider care-in-the-community policy is working, pegging the feature to yesterday’s speech by the Health Minister in the House of Commons.

A general interest magazine might accept a piece summarizing the newspaper article and following it up with accounts of how one or two regional health authorities interpret the policy. This could be done effectively by case studies contrasting treatments inside and outside institutions in each area.

Research sources will include MENCAP and the British Institute of Medical Handicap, which produces the journal Mental Handicap Research.

If you have time to take plenty of notes on a subject, you may want to make a list of the publications you read, and write for, and ask yourself what aspect or angle they might be interested in.

While developing ideas and studying the market as described in the following chapters you will see more precisely how a feature can be reshaped in different ways and, after a pause, updated.

A script for radio or TV

This is outside the scope of this book, but see the Bibliography for guides to writing for broadcast.

Books

The outline for a feature of length and complexity can easily be expanded to provide the framework for a book. An example is given on page 165.

Ideas for non-fiction books will come when you have devoted a fair amount of time to a specialism. After publishing a dozen or so articles on a how-to subject, for example, you may well decide you can develop the material for a book.

ASSIGNMENTS

1 Take three articles (approximately 500, 800 and 1500 words) from different publications. Produce a clear outline of the content of each by listing the main points in note form (not sentences), one point for each paragraph. Point out where you think the structure could have been improved.

2 Change each of the above to a sentence outline, indicating links.

3 Rewrite the following paragraphs, the intro to a student’s article, ‘Euthanasia: Mercy Killing or Murder?’. Reduce to 80–90 words. Improve the structure and make it less academic. (For a popular woman’s magazine.)

Whatever area of nursing nurses find themselves in, from geriatrics to hospice or intensive care, as nurses, they are confronted by patients whose condition is so severe, or whose quality of life so questionable, that thoughts of euthanasia inevitably cross their minds. These thoughts can throw into turmoil all that their training has taught them about the preservation of life and cause them to confront their most deeply cemented ethical beliefs. This article attempts to explore the differing opinions on euthanasia, from a nursing perspective. The primary question is whether it is in our society’s interest to change the current law against euthanasia in Britain. This has far-reaching implications, outlined later in the article.

I have spoken to Philippa, a senior nurse with several years experience of working with the terminally ill, who remains unconvinced that causing the premature death of a patient is a viable option in the ongoing quest to relieve suffering. I have also spoken to Anne, a retired nurse who endorses ‘active euthanasia’. From these opposing viewpoints, I hope this article will provide the basis for further discussion and research into this very difficult and emotive subject. It is my personal belief that ‘active’ euthanasia goes against the very grain of nursing standards of practice, which endeavour to provide dignity, comfort and support to those suffering long-term and terminal illness.

4 Workshop. All students of a small group (up to eight) write an article of 600 words at home with the same title and target publication. The completed scripts are collected and distributed so that each writer gets someone else’s. Each writer now becomes an editor, subs the article and writes a letter suggesting how it might be improved and possibly commissioned. The editors may be anonymous or not: try it both ways. Each student then reports on the editing done to their script, indicating their response. The tutor guides group discussion on each script.

A large group can split up into two or three small groups, each operating as above, each with a different title/target, after which the tutor can work through the scripts immediately, guiding the group discussion.