4 The world of ideas

Editors want ideas, not subjects. Racism, and Racism in London are subjects: if you propose either to an editor you will be asked what your idea is. Or your viewpoint, or angle, or slant. The synonyms and near-synonyms for ‘idea’ in journalism are many.

The idea is extracted from a subject. The Ignorance that is Racism is an idea. The angle or viewpoint is clear. But it sounds more like the title of a book than of an article. It might make an essay type of column for an intellectual weekly but it is too large an idea for most publications.

Narrow it down geographically (The Ignorance that is Racism in Bradford’s Schools) and you may have a likely idea for a local paper in the Bradford area if it hasn’t been aired there recently. Narrow it down thematically (Pre-School Infants Are Not Racist) and you may have an acceptable idea for the education section of a national paper or for a women’s magazine. You twist a subject into focus, you make an angle. The Danger of Noise can become Discos Can Make You Deaf, The Police in Britain – When Should the Police be Armed?

This chapter describes:

• staff writers’ ideas

• freelance writers’ ideas

• development techniques

• the place of specialism.

STAFF WRITERS’ IDEAS

The staff writer has the advantage of living in a familiar world of ideas that has built up round the publication. There may be editorial meetings where feature writers can bounce ideas off each other, or this may happen informally. Press releases and other literature, arriving daily, suggest possible topics for features. Staff writers can judge immediately which ideas fit the publication they work for. Furthermore, staff writers are backed up by extensive resources. Ideas come to staff and freelance writers in different ways, but they can learn from each other.

If you’re a freelance, put yourself in the editor’s shoes. If an idea is going to need plenty of time, expense and resources, it will probably be given to a staff writer. This will tend to happen if there’s a risk inherent in the idea – that it might not come off, for instance – or if it will need careful day-by-day developing in the office.

Ideas out of news

Reporters on local papers begin to turn into feature writers when they develop straightforward news reports into news features. For example, a reporter is covering a landslide into the sea. Cracks have appeared in houses near a cliff edge. The district council says the houses will now have settled and that it is planned to shore up the bank with some boulders to prevent further erosion. End of news story. But the editor tells the reporter that ten years ago the same reassurances were given to people living in an isolated house near a cliff edge some miles farther down the coast. Their house collapsed in the middle of the night, and they were lucky to escape with their lives. A sea wall was eventually built.

‘Investigate it,’ the editor says. ‘It may be that the sea wall will have to be extended. Get as much as possible from the cuttings, then go back to the surveyors on the council.’

The reporter might discover from cuttings sources that might be contacted, not only to update on the topic but to extend it and develop a more ambitious backgrounder: the Department of the Environment, the Professor of Geology at the nearest university, the local secretary of the Farmers’ Union perhaps. The editor is persuaded to allow more time. A feature has been born.

A sudden spate of foxes killing chickens, burglaries on an inner-city housing estate, road accidents on a dangerous corner and the selling of gifted players by the local football team though its performance is deteriorating are other stories that might similarly suggest background features on a local paper. Some might be worth a freelance rewriting, after widening the research, as spin-offs for national publications.

Ideas out of press releases

Press releases may yield a feature rather than a news story. A local paper receives a brief one about a novelty act called The Three Charlies, based locally, which involves clowns combining playing instruments, juggling and contortions. The release mentions that the trio has achieved some national success and has TV and film engagements lined up. Without much change, the release makes a news item.

But a feature writer is asked to get more. The paper’s cuttings library and microfilm are studied, the publicity agents are contacted, the performers interviewed. The show, it is discovered, is based on a famous music hall act at the turn of the century. There are articles on the original troupe performing at the now defunct theatre in the area. A local antiques shop has posters that can be reproduced. The feature makes a page.

From the inside

On a regional paper of some standing and on nationals ideas are both originated and developed in editorial meetings: preliminary meetings of section editors with their writers will often precede the main editorial conferences of newspapers. At these the editor checks on the progress of news and feature projects with section editors. Everyone will have read the morning papers.

Ideas will be expressed about how to follow up, improve on, or scoop the stories rival publications contain, as well as ideas about how to move forward the projects that originated in-house and that they hope their rivals haven’t got wind of.

Decisions will be made about whether a story is better treated as straight news or, with more space and analysis, on news review or ‘Focus’ pages, or whether it is general feature material. A project may begin in one camp and end up in another. A features editor will watch current news stories.

Ideas out of the letters page

Ideas from staff writers or suggested to them are especially valued if they encourage feedback from readers, and a debate can, with skilful subbing, be continued for several issues. Readers are sometimes invited to respond to controversial pieces, by email to the writer if not in a letter to the editor. The People engineered a debate in this way:

Last week The People told the heartbreaking story of tragic Dad Nigel Nelson whose brain-damaged baby daughter Naomi died after he increased her dose of pain-killing drugs. We asked you to tell us whether intolerable suffering justifies mercy killing. Your verdict was an overwhelming Yes, and our postbag contained some of the most moving letters we have ever received. Here is a selection …

FREELANCE WRITERS’ IDEAS

The distinction between staff and freelance ideas is blurred to some extent. On the one hand freelances have access to increasingly sophisticated resources such as the Internet, and on the other hand staff writers increasingly write at home. A freelance closely associated with a publication will operate in much the same way as the staff writer described above. And although what follows has the freelance mainly in mind, a staff writer is often working as, or like, a freelance.

Some freelances have launched themselves out of staff jobs and have inside knowledge to carry with them. Some specialize as columnists or reviewers for one or two publications. But the tyro freelance may have to be adept at finding different kinds of ideas and at matching them to different targets, and will have to provide their own back-up resources at home or in libraries.

With targets in mind

Professional golfers about to compete on a golf course spend many hours getting to know the course in practice rounds. They get to know the shape of it well, every bump in the ground, the contours, the gradients, the length of the grass in different parts. They can then play it in their minds. Professional feature writers about to compete for space on a publication do a market study of the publication.

Suppose you want to tackle Bullying in the Workplace. Suppose you make this list of target publications: the Daily Mail, The Guardian, The Economist, Business, New Statesman, Woman’s Own, Marie Claire, The Lady, Men Only, GQ and your local paper. You realize that you haven’t got one potential feature but many. Unless you have an impressive track record, of course, you would find many of the publications difficult to break into.

Here’s a suggestion for how to proceed. Take a close look at your list and decide which are the most likely prospects for you. Each publication will require a different treatment: it will require you to answer the questions about the subject that its audience would ask, in such a way as to command its attention. Treatment involves angle, content, structure and style. You study each publication carefully (several recent issues) and decide on the kind of treatment that will work.

You will consider, for example, which publications will be most interested in the effects of the bullying on the efficiency of the company, which on the psychologies of bullies and victims, and you will decide what range of workplaces would be covered by each publication. Which will want drama, which cool reasoning? What lengths do features in each publication run to? Which go for humour, which lean towards academic seriousness?

As examples, the Daily Mail and The Guardian, you deduce, will bring politics into it, The Guardian (having many teachers among its readers) will relate it to bullying at school. The Economist will be interested in the damaging effects of bullying on the efficiency of businesses, Woman’s Own in how parents can help victims. Would your local newspaper do a survey of the local schools, perhaps using a questionnaire that both teachers and pupils would be asked to complete? How would you develop the idea for each of the other publications? Having chosen a target, you check that the subject hasn’t been dealt with recently and that their editorial policy for features hasn’t suddenly been changed (for example, by a new appointment).

You may prefer to do it more the other way round, to concentrate on getting ideas developed before looking for targets. (You want to make sure you will produce something that fits but is somewhat different from the usual fare perhaps.) Whichever, once established as a regular writer for a publication, the whole process will be more of a collaboration with the editor, who will adapt a briefing policy to what they know you’re capable of. These are matters for the following chapters. Let’s get back to the ideas.

Finding the idea

Freelance writers have the advantage that they can come up with the more unusual ideas. Publications can get in a rut sticking too rigidly to a formula. Editors can then be excited by the passion and commitment of a freelance with fresh ideas and above-average writing ability.

Freelances are sometimes paid for a good idea, especially by newspapers, when a staff writer is considered to be better placed with connections, and better qualified generally, to develop the article. But don’t give too much away before getting a commission: ideas can be pinched as well as pitched.

You need to be open to ideas and ready to capture them. The poet Louis MacNeice spent 25 years learning how to write poetry, then suddenly one day realized he had poems flying past his right ear. All he had to do was move his head a bit to the right. The German poet Schiller found ideas came more rapidly if he had rotting apples in a drawer of his desk. Ernest Hemingway sharpened a lot of pencils before starting to write. You will find your own ways of getting into a receptive state of mind. Be as mystical about it as you like if it works. For the moment we’re on a practical level.

As journalists, you need to be practical, in terms of size (seriousness, importance) of idea, in kinds of market aimed at, and in day-to-day procedure. To repeat: carry a notebook and pen everywhere and leave them around your home. For many ideas will come when you least expect them. Some will come in the form of a word or a phrase or a sentence, perhaps a title. Others will demand a page or more of your notebook. Transfer likely ideas to a folder where they can be developed by adding notes, cuttings and other printed materials or start computer files for them. (See Chapter 2.)

Where should you look for ideas? Here are some likely sources.

Personal experience

Features can be written about first- or second-hand experience of, for example, the domestic upheaval of moving house, a change of career, office politics, dangerous dogs, a conversion to Buddhism. And so on.

It’s probably best to develop such a piece with a target in mind. In which case, make sure that it will appeal to the readership aimed at. It’s too easy to assume that what has deeply affected you will interest others. There have been numerous articles published on such topics as those listed above, so what have you got to add? Can you think of a fresh treatment? Can you combine your experience with that of others gleaned from your cuttings files? Can you think of interviewees who would add a dimension or two?

Conversations noted

At a party you’ve been identified as a good listener by a woman of a certain age who is being lengthy about her studies as an Open University student. You are edging away when she says, ‘I had to do something when I lost my husband and two children in a car crash.’ You begin to contribute to the conversation. You won’t whip out your notebook right away but you may ask if she would mind your taking a few notes for an article you see on the horizon.

In a pub you hear two men in the tiling business discussing how they avoid the tax man. You may get some ideas for an article on moonlighting. You may like to make some surreptitious notes on the newspaper you are carrying, since using a notebook might arouse suspicion. You may get into conversation with them if you don’t look too much like an income tax inspector, or if they aren’t too big, and you can choose your words carefully.

Events observed

Deepen your particular interests and areas of knowledge by attending associated events. If you want to write features for a local newspaper, find out which organizations and activities are not covered by the paper. Scouts, street entertainers, swimming galas, surviving rural skills, amateur dramatics, restaurants guide? Then develop convincing arguments for their inclusion and send those arguments to the editor with some samples of your writing.

If you are taken on as a regular contributor (which could lead to the offer of a staff job), not all your reports are going to be used, but you might be able to negotiate a retainer fee. Put yourself on the mailing lists of the organizations. Attend some meetings and make yourself known to the chairmen, who will telephone you with the dates or results of future ones. Having contributed news items to the paper on this basis for a while, you may find it easier to get space on the feature pages.

Editorial departments of newspapers and magazines have a printed or computer-screened diary of forthcoming events that staff reporters and feature writers will cover. The diary includes anniversaries that may provide a ready-made news peg: of the birth or death of a famous resident, for example. Past issues will be studied to make sure the resident hasn’t been dealt with too recently and that the new story has freshness.

Freelances often keep their own diary or concertina file for forthcoming events they may decide to write up, noting especially those related to their particular interests and the kinds of events that have been overlooked by publications considered likely markets.

Broadcasts

Radio phone-in programmes, like the letters pages of newspapers and magazines, are natural homes for the cranky and the quirky and can be a fertile source of ideas. Child abusers should be castrated, you may hear someone say, or sterilized, or nothing at all should be opened on Sundays, or the public schools should be abolished and the buildings used to house the mentally ill. Such remarks may amuse or annoy: they probably start you thinking about the subject.

Be on the lookout for broadcasts that deal with topics you’re thinking about or have begun to write about. Radio and TV documentaries on such subjects as drug addiction, the prison system, immigrants, increasing obesity and business frauds may throw up some aspect that grabs you: then you grab your notebook. Such programmes will suggest possible contacts. Note that tonight’s TV documentary may have been made a year ago: check and update the material.

Printed sources

Read widely for ideas and develop a system for extracting them: from newspapers and magazines, from books, and from other literature – publicity material from business organizations, for example.

Newspapers and consumer magazines

Let’s get back to your cuttings library and look at it more closely.

Read the popular as well as the quality prints. Collect cuttings that add something new to one of your subjects, that may suggest future features or provide facts for them. Collect also cuttings of articles you consider good models for particular kinds: for a celebrity interview, a political background piece, a film review or whatever. Paste the most useful on A4 sheets, photocopy (to preserve them) and file. Indicate origin and date, so that you will know how to update them when the time comes. Make comments in the margins so that you won’t wonder several months later why you cut them.

Do all this regularly and avoid hoarding whole publications, which can soon take up a lot of space. Read in libraries and use their photocopiers. You may want to file the sheets of cuttings in subject files, or collect them in envelopes, with some means of reference. Have a clear-out occasionally, replacing cuttings with fresher material. It’s a good idea also to collect cuttings of articles that you consider models of effective techniques – for structure, for an original use of language, in the employment of anecdotes and quotes, or whatever.

The contents pages of discarded magazines can suggest new ideas in themselves. A good tip when extracting an idea from one market is to reshape it for another where it will be less familiar. A medical breakthrough analysed in an upmarket weekly may lend itself to a more light-hearted human interest treatment for a popular paper or magazine. Conversely an interview with a young woman in a local paper who has survived a dysfunctional family and drug addiction and launched a career in television may suggest how some researching will discover stories that might add up to a feature for a national magazine.

Subscribe to Press Gazette to keep up to date with the journalism business, and a writers’ trade magazine for up-to-date market information and articles on idea forming and writing techniques.

Returning to the letter pages, note that subjects come and go in cycles. The following were aired in the mid 1990s but are on the go again in 2005 (so you may want to keep informative cuttings on your favourite themes until they’re quite superseded): ironical letters about farmers claiming to be defenders of liberty when footpaths are blocked to ramblers by barbed wire; letters adamant that young offenders (under 18) are best dealt with in the community than by locking them up. When you have cut an article expressing a strong view and the following week a letter responding forcefully with the opposite view, you can be well on the way to your ideas on the subject.

Don’t over-file though. You can access much up-to-date material, including newspaper and magazine features from archives, quickly on the Internet. Note what’s free and what isn’t.

File when you see an idea lurking in a subject rather than when you see a subject that might, or might not, produce an idea.

For example, file when you see information that’s unusual, not readily available elsewhere, or which appears in an article where you didn’t expect it. You read the run-of-the-mill travel or tourism piece and what catches your attention is a remark about the difference in the ways hotel managers treat guests in different countries. Just a remark but, wait a minute, file it: that could be developed.

Business-to-business magazines and professional journals

Some news stories don’t break in newspapers but in business-to-business magazines and professional journals. Keep an eye on them. You can corner ideas worth wider dissemination.

You spot in a catering magazine, for example, that a famous hotel company, in its bid to take over another, accuses the latter of various management faults. One fault mentioned is a failure to use efficiently technology new to hotels. You note that this aspect has not been covered by newspapers or the business magazines, which have concentrated on the financial aspects of the conflict. Names are mentioned in the catering magazine article that could help you to write a piece on the new technology, or lack of it, in hotels. A national newspaper or a consumer magazine might be interested.

Such ideas frequently revolve around new products or new technology. Information in a business-to-business or technical journal about a new kind of computer for use in schools, or about a court case concerning an accident caused by a department store escalator breaking down, may have wider implication. The news media may not immediately realize the news value of such stories or see how to interpret them to a wider audience.

Ideally placed to do so would be part-time freelances whose main jobs are in hotels, computer technology and store management. In journalistic terms, they are the ‘experts’. But your most valuable trick is in knowing who the experts are and in getting them to talk to you.

Books

Reference books of various kinds are worth digging into. Consider Chambers Dictionary of Dates. Take the section 25th March: ‘1843 – The 1300 foot Thames tunnel, from Wapping to Rotherhithe, was opened. 1867 – Arturo Toscanini born. 1975 – King Faisal of Saudi Arabia assassinated by his nephew.’ Some library research into these subjects will develop ideas about famous tunnels, musicians, assassinations. Staying with anniversaries, reference books of different kinds can tell or remind you when Mothers’ Day is and Fathers’ Day, National Condom Week, Wake up to Birds Week, and so on. But avoid the anniversaries all those other freelances pick up.

Looking through the London South East Yellow Pages telephone directory I find the following intriguing entries: chimney sweeps, diamond sawing, fallout shelters, gold blockers, hairpiece manufacturers and importers, naturopaths, noise and vibration consultants, pawnbrokers, portable buildings, robots, ship breakers, toastmasters. Nothing stirs you? Have a go yourself in your local Yellow Pages.

Other literature

Newsletters, pamphlets and press releases from government departments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), including charities and pressure groups, academic institutes and business organizations are other sources of ideas and information. Such literature pours into newspaper and magazine offices. As a freelance, put yourself on mailing lists. A word of warning here. The ideas those organizations are promoting won’t easily fit into feature articles without your assessing their validity. You will recognize particular agendas. You will, for example, check what the Department of Health says against what MIND says, what the Department of the Environment says against what Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth say.

An advert for a special luxury object catches your eye. ‘Two fine examples of Chinese lacquer. The larger can be found in the British Museum, the smaller in the High Street.’ What are the other uses of lacquer today, you wonder. Who else uses techniques over 2000 years old? Is there an article in it? Who would be interested in such an article?

An advert for unit trusts in The Financial Times is headed ‘Why the Meteorological Office should be staffed by giraffes’. That is a good title. It makes you wonder what other animal habits, as well as those of giraffes, signify changes in the weather, and what angle could be given to that. Or perhaps you’re more interested in pursuing the idea in the advert. You may ask yourself how reliable are the predictions of stock market movements made by analysts who believe they come in cyclical patterns.

Computerized sources

A computer gives you access to a great deal of journalism and the indexes to publications to enable you to locate articles dealing with your subject. At the research and development stage you can key your subject word or a related one into your search engine and you will be led into worlds of possibilities. You will be able to locate quotes, anecdotes, extracts, article and publication titles, book titles, names of experts, websites of likely contacts.

The websites of organizations that relate to your areas of interest and that give out up-to-date news of their activities may be good sources of ideas.

DEVELOPMENT TECHNIQUES

Whether you’re a staff writer or a freelance, or both, you need techniques to make your ideas grow. Ideas are tender plants. Some you’ve just got to let grow; others you’ve got to feed and watch over; others are beyond any surgical intervention. You will find your own ways, but you may want to experiment with the suggestions below and discover what sort of activity works best for you.

The growing process, as described earlier, is probably best done inside a folder. Start off a folder by collecting as many cuttings/notes as you can, add to the folders when you can, and go through them regularly to remove the out-of-date ones and decide when you’ve got a good idea to sell.

At any stage of this development, however, you may want to experiment with different brainstorming methods to see what fits the idea or your way of thinking. Here are a few suggestions.

Putting the imagination to work

Imagination is, generally speaking, putting things together in new ways. In journalism the originality of an idea resides in treatment – in the angle, in the style, in the structure, in avoiding the obvious content. You gather your information from places not too familiar, you find your own contacts if you can that know more than has been revealed, you talk to the not-so-obvious sources.

On a simple level: you read that a country horse event is to take place next Saturday. You decide to attend and write an account of the event as seen by a man who cleans out the stables. You are angered by a shop assistant’s lack of interest and courtesy, and you decide to write an article about it, perhaps comparing the British worker with the French or Spanish counterpart. But you do a bit of research and discover that this view has been aired frequently. You decide to develop the theme from the point of view of the shop assistants.

On a more complex level the power of imagination helps you to yoke together disparate notions in inventive ways. As a feature idea grows and you have notes from various sources you need to use your imagination to experiment with them, juxtapose them in different ways, to liberate yourself from the weight of information, to let illumination in. Sometimes you will find yourself on an unrewarding journey, and you may have to abandon the trail and start again with another brainstorming method.

Using formulas and word associations

An idea can begin with a word or phrase that lodges in the mind for no particular reason.

‘Animal’ can turn into ‘Animals Anonymous’, and that might suggest animals with behaviour problems being organized for some kind of treatment, or more sinisterly, for genetic experiments.

There are formula ideas, hundreds of them, that work well for popular markets: What Your … Should Tell You About Yourself (hand, handwriting, earlobes), What Is The Best …? (age, diet), The … Of The Future (toys, careers, bodies), Behind The Scenes At The … (opera, TV centre, film studio, football stadium), The World’s Biggest …, The World’s Smallest …, Can … Survive? (personality, conversation).

Some intriguing lists can be turned into articles: The Great Bars of the World, The Best Hotels. But of course most of them are overdone, so turn the ideas on their heads: The Worst …, The Cheapest …

Putting two subjects together can make an idea. The police by itself is a subject. Ideas are there already in the police and arms, the police and race, or rape, or TV, or interrogation techniques, or the law, or football hooliganism, or politics.

Looking at a subject’s contrary can make a possible idea: for example, Fortunate Accidents, Unhappy Millionaires, Ingenious Mishaps, Tragic Trifles. Such phrases at least start you thinking.

As some of these formula examples show, a good idea can come to you in the shape of a good title. But a good title is sometimes hard to find, and the ones that immediately suggest themselves may be well worn. Work at finding a good title because that will help you develop the idea and keep you on track. Experiment by listing possible titles on a piece of paper or on your screen. Try to make them reflect your angle and suit the publication aimed at.

You might have a problem interesting an editor in a piece on The Danger of Noise; Discos Can Make You Deaf will perhaps have a better chance. Such alliteration helps to make them memorable, as do rhythm and puns and other verbal tricks. On the other hand, you have to avoid using these factors in predictable ways.

Many titles are changed by the subeditors. Your title has to harmonize with the other titles in the issue, and if you aren’t a subeditor you cannot usually anticipate them, nor the design of the page where your article will appear and therefore the size wanted. The subeditors are closer to the readers and may have special expertise. Nevertheless, work at creating a good title, or at least a good provisional title, because it will help you to sell the idea or the article, and to keep you on track. When the piece is accepted, the subeditor will have something to work on.

Linear-logical thinking

Developing a feature outline from a subject in a linear-logical way can unleash a few ideas. You see the possibilities and can select an aspect that strikes you as fruitful. Suppose the subject is surgery and your angle the question: is it skilful enough? You might discover such a pattern as:

• Medical training for surgeons

• Where technology is up to date

• Where lacking

• Cutbacks in the Health Service

• Priorities in budgeting

• Criteria?

• Too many errors?

• Law

• Ethics

• Compensation

• Insurance.

If you’re knowledgeable about a subject and know more or less where you’re going this way of thinking is productive. If you need to be open to different possibilities, if you want to discover how you see a subject, to stimulate your thinking about it, the linear-logical approach can be restrictive and a brainstorming technique is recommended.

Lateral thinking

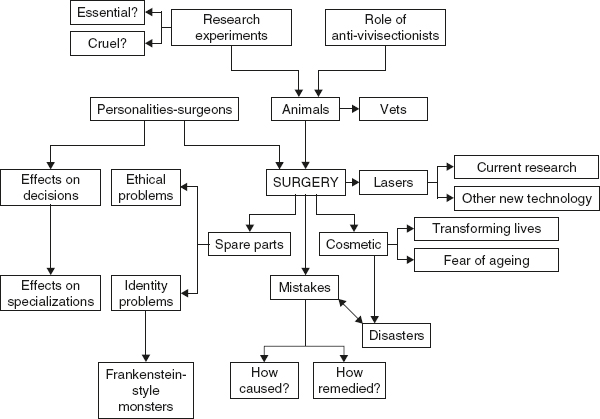

Try putting ‘surgery’ in the middle of an A4 page and fan out the promising associations as they come into your mind: make a mind map. Keep a measure of control. Then compare the result with Figure 4.1. You will find that the words and phrases will work on each other, and you will be encouraged to make unusual and interesting associations. Your thinking is encouraged to become more original. You can then select that part of the map that you want to concentrate on.

Free association with words and phrases can produce a similar effect. Still with ‘surgery’ as my subject, I open a dictionary and write down words at random: candle, cry, danger, fence, left-handed, meeting, nerve, pact.

Figure 4.1

A mind map with the subject ‘surgery’

‘Candle’ makes me wonder about any out-of-date equipment, ‘cry’ what proportion of victims of errors complain. What would a list of recent surgical errors suggest are the most likely dangers? What is being done to avoid them? Are many errors hushed up? Left-handed – how often do physical weaknesses contribute to errors? What screening is made of surgeons? Do they have to undergo tests periodically? After a mishap, what meetings take place? Who are present? What pacts are made? Nerve – how often does the anaesthesia go wrong? Once you have gathered questions or points by brainstorming, you can allow logic back in to outline your article.

Computerized brainstorming

There are computer programs that generate ideas by word association brainstorming. A sophisticated one is the American IdeaFisher. This is an interactive database of questions and an ideas thesaurus (you can get more than a thousand associations for one word) used by a great variety of companies for which communication, problem solving and strategy are priorities. This is expensive but you may want to explore such aids. They may not suit the way you work.

IdeaFisher combines with Tony Buzan’s mind maps organization. Have a look at www.mind-map.com.

In general you can simply key a word into your search engine and you’ll be able to follow up various pathways via associated ideas, contacts, book titles, quotes and quotations.

You can use your computer to brainstorm as you scroll through a feature, having your text on the left of the screen and using the right side to generate ideas or jot down notes that may be incorporated later.

Try trawling through the newsgroups and other discussions. Subscribe to likely mailing lists, but select wisely and don’t get overwhelmed with emails that you don’t find interesting.

THE PLACE OF SPECIALISM

Subjects are in and out of fashion, magazines come and go, so feature writers are wise in the early stages of their career to develop ideas out of a variety of interests. In any case your interests will vary as you get older, and a lively curiosity about the world in general and in people of different age groups is needed if you are to communicate with wide readerships effectively.

Write about what you know, especially perhaps when starting out, but keep in mind that it’s what your readers need or want to know, and that you can find out, that’s important rather than what you happen to know. An idea is a paltry thing unless it can be supported by facts and put across persuasively.

At the same time it’s good to have a specialism or two because specialist magazines are numerous. Newspaper editors will begin to remember your name. They will begin looking for you when your subjects are in the news, and you will welcome the time you can subtract from selling and add to writing. Making a mark in specialist writing can lead to work in broadcasting.

Of course, once you are well established with a specialism or two, you may need to concentrate on them. But don’t let specialisms take you over completely. Theatre and music critics, for example, can impress with their analytical powers yet disappoint if they show few signs of knowing much else.

CHECKLIST

You can waste a lot of time not only writing pieces that are rejected but outlining ideas that are rejected. After doing some market study but before proposing an idea to an editor, put it through a test. Here’s a checklist to help you decide whether your idea has potential or not:

• Is the idea too broad, or too narrow?

• Is it fresh, or has it been overdone recently?

• Can you update the published information you’ve seen recently on the subject?

• Is fresh information readily available? Where from?

• Will the idea appeal to the target readers?

• Are the facts likely to be of the kind that the readers will need or want?

• Is there a clear theme/angle/point of view?

• Is the idea significant, important, relevant, timely?

• If not timely, does it have enough timelessness about it?

• Is it a good time for you to handle it. Why?

• Are there any dangers of libel, or other legal or ethical considerations?

• Do you really want to write the feature or do you think of it as a chore?

• How much will the feature cost you in money and time?

• If it doesn’t work for your target editor, might it appeal to others?

ASSIGNMENTS

1 Try a mind map with one of the following subjects: noise, dyslexia, fox hunting, earthquakes.

2 Use the mind map you’ve created to extract an idea for a feature of 600 words and write it, indicating the target aimed at.

3 Your subject is Good Manners. Here’s a list of words taken at random from the dictionary. Do any of them, or any combination of them, suggest an interesting angle/approach to the subject? (If they don’t, try making your own list.) Produce three possible ideas for three possible targets:

cynical, fingering, gazump, hostile, injure, linear, passable, segregate, spy, trance, unfortunate, war dance.