CHAPTER 6

![]()

ORGANIZATIONAL APPLICATION

Culture is the deeper level of basic assumptions and beliefs that are shared by members of an organization.

—EDGAR SCHEIN, ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE AND LEADERSHIP

The preceding chapters have focused on you as an individual. We have talked about your Belief Window and whether you are meeting your needs over time. But each one of us is more than just an individual. We are members of a number of organizations, from families to corporations. Whether you are an employee striving to make a meaningful contribution, an executive trying to steer the ship, or the head of a family, this chapter is for you.

Meeting Our Needs over Time

I don’t think anyone sets out to “meet payroll” or to build an organization like we did at Franklin Quest, where literally thousands of families rely on the decisions you make every day. But we did build that organization, and we did assume the responsibility—in partnership with everyone we worked with—to serve our customers, to meet payroll, and to make a difference in people’s lives.

And, when you do that, you jump into the deep end of the pool: everything the Reality Model is about. There were many times in the building of this global company that I consciously asked myself, Will this decision meet our needs over time?

And I do know that that question matters as much in the boardroom and the executive suite as it does anywhere else. And maybe it even matters more there, because so many people rely on the answer and because we’re dealing with real life, real consequences, and real outcomes that have real and lasting impacts on people, their lives, and their relationships.

This part of the book is about being a leader, holding leadership responsibility, and trying to do the right thing day in and day out. And in knowing that the right thing shares, at least in part, the very real question and the answers it drives: Will this meet our needs over time?

This is about applying what we’ve learned about the Reality Model in the preceding chapters to our managerial and leadership responsibilities. As a leader, I’ve learned that the Reality Model and the principles it’s based upon are always at play—at home and at work. This chapter is about the “at work” part.

Leadership and the Human Needs Pyramid

A dictionary definition of the word organization might be a “group of persons and things dedicated to a specific goal.” In other words, organizations are nothing more than groups of individuals taking things (resources) and focusing them, and their energies, on outcomes that will hopefully meet their needs now and over time.

Since organizations are made up of individuals, it makes sense to me that the needs that drive one person are probably very similar to—if not exactly the same as—the needs that drive an organization.

Let’s reexamine the four Human Needs in an organizational context.

The Need to Live (Physiological Need)

People need food, shelter, water, safety, security, and all of the other things that Abraham Maslow and others have mentioned. I’m going to use Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, first expressed in in his 1943 essay “A Theory of Human Motivation,” to frame the Reality Model and an organization’s needs.

Organizations, like individuals, need to sustain life. Organizations don’t eat chicken, mashed potatoes, and peas. What they eat is money, markets, inventory, and all of the other materials that allow them to find, serve, and retain their customers. If you don’t think organizations, like people, have to eat to live, you’ve never seen the changes that occur between the top and bottom lines of an income statement or a balance sheet. Organizations are hungry, and it’s a leader’s job to feed that hunger yet to keep the organization lean (though not too lean), to give it the energy it needs to get through the day, the month, and the years to come.

The Need to Love and Be Loved (Belonging)

If you want to guarantee a phone call from your Human Resources department, as a leader of an organization go out and teach everyone that we, as members of the organization, need to “love and be loved.” I think that, as a general rule, we ought not to take the “love and be loved” idea too far in an organization unless we’re running a family business. But if we get to the real root of that statement, we’re right on target for understanding how this need works in an organization. The need to love and be loved is a profound form of the need for relationships. We all need and want them.

As the great poet John Donne wrote, “No man is an island.” We are in this thing together. Relationships matter. In fact, as my friend Tony Robbins has said, “The quality of your life is in direct proportion to the quality of your relationships.” And since you spend so many hours of your life at work, relationships at work are vital to your emotional well-being.

If your employees and team members are enjoying healthy relationships, then that need is met and your organization is on its way to flourishing. As in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the need to love and be loved cannot stand alone, but it provides one of the building blocks of a healthy organization.

Relationships are the foundation of the culture, and the culture in an organization is what holds the strategy and the vision and processes together. A dysfunctional culture certainly affects your strategy, your vision, your processes, and your bottom line.

If you’re not quite sure how important relationships are to organizational success, watch an organization try to function that has operational “silos.” Watch the waste created through duplication of effort and crossover when Department A is not talking to or strategizing with Department B. Watch the confusion that reigns when the strategic vision in the Northeast Region is at cross-purposes with that of the Southwest Region. If you want to see how important the relationship need is to organizational health, simply observe the consequences of its absence.

Nothing will tear an organization apart faster than toxic relationships in the boardroom or on the senior team. Fractured organizations are not accidental; they are the consequence of relationship failures at the highest levels of the organization. You don’t need your senior team to “love and be loved” in a sentimental way, but they darn sure better have quality professional relationships and respect; if not, you’ll see a toxicity wash through the entire organization.

If you want a healthy company with the potential to meet its needs over time, to be here next Friday and twenty years from next Friday, work on the quality of the relationships at the highest levels of leadership.

There’s some argument among economists as to whether “trickle-down economics” really share the wealth in a group. I’m not an economist, but in the area of executive leadership I’ve got more than enough experience—both positive and negative—to know that “trickle-down relationships” can either steer the corporate ship into the safe channel or onto the rocks.

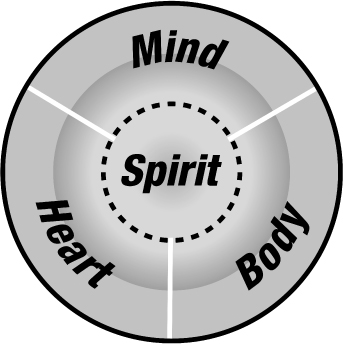

Relationships matter. An organization consists of people, but a whole person is made up of a mental dimension, a physical part, a social/emotional part, and a spiritual part. In simple terms: mind, body, heart, and spirit. It is what my friend Stephen Covey has referred to as the Whole Person Paradigm.

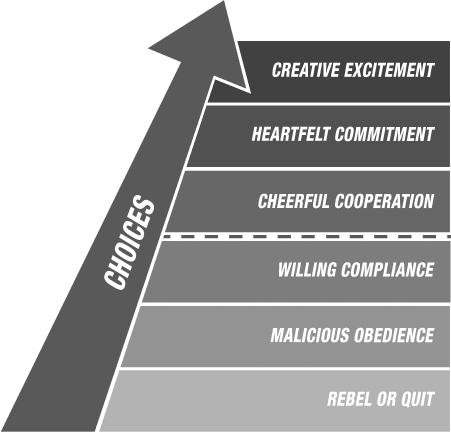

When you acknowledge the importance of relationships in an organization, you look for ways to engage the whole person: his or her mind, body, heart, and spirit. Do not doubt this fact: if a relationship is suffering, the entire output for the organization will suffer. Why? As Covey has written in his book The 8th Habit: From Effectiveness to Greatness, “People make choices. Consciously or subconsciously, people decide how much of themselves they will give to their work depending on how they are treated and on their opportunities to use all four parts of their nature. These choices range from rebelling or quitting to creative excitement.”

At Franklin Covey we published the Employee Engagement Model; it recognizes the importance of relationships and the fact that employees have choices. At the lowest level, they can rebel or quit, and at that level you honestly hope that they quit. At the opposite end of the model they feel a creative excitement about their opportunities. At this level, through your healthy and positive relationship with them, you have been able to engage the whole person. Relationships do matter.

The Need to Feel Important (Esteem)

As I have traveled and taught these principles to people all over the world, I’ve learned that there are some elements of business culture that are far more American than we realize, and then there are elements that are universal.

For example, one of those elements of business culture is sports and its relationship with business. People everywhere love sports; in fact, the cultural and individual love for football (what we call soccer) is so profound in areas outside the United States as to be almost incomprehensible to most of us. If you think the Super Bowl is a big deal, understand this: it lasts one weekend per year. In most of the world, the World Cup lasts an entire month and the final game is watched by over 500 million people.

Accepting that a passion for sports is a global thing, it’s always been interesting to me how much more we, as Americans, are ready to embed sports into business—and especially business leadership. Many American business leaders know the Vince Lombardi quote; some have it framed on their office wall: “Winning isn’t everything; it’s the only thing.”

There’s no such thing as a “Who’s Lombardi?” group leading an American business. I don’t know why this is. Maybe it’s because, growing up, most of us experience the realities of sports before we experience the realities of business. Maybe it’s because the metaphors and parallels are so obvious. All I know is, you’re not likely to get through a day of business without some discussion of sports and its connection to business.

One of the great things about sports, from the little league to the professional level, is that it simplifies the complexities of life. There’s a game; there are some rules; and there’s the opportunity to win or lose. As much as people try nowadays to give everyone a ribbon for just showing up, we all know deep in our gut that you have either won or lost.

You didn’t show up “just to have fun.” You got on the field or the court or the pitcher’s mound to do one thing: to win. And that’s what makes business and sports such obvious companions. Business isn’t about trying; it’s not about “having a good time.” It’s about winning, because those who win make payroll; those who don’t, don’t. It’s about that simple.

And it’s in the pursuit of winning that we have the chance to contribute, to be a part of something bigger than ourselves, to put our talents, our brains, and our hearts on the line. It’s in the pursuit of the win we can make a difference. And it’s in that moment of making a difference that we feel important.

Of course, you don’t have to win to feel important. But having won some and lost some, I know this much: it’s a lot easier to feel important when you’re on the winning side. It’s a lot easier to see the genius of your idea, the value of your suggestion, the power of your creativity, when that input creates output.

I don’t know of many people—unless they believe they can turn it around—who want to join a losing team. We want to win. We want to make a difference. And when we do, we feel important.

Too often organizations focus on the idea of recognizing people as the key to making those people feel important. Recognition matters, but it’s a whole new ball game (there’s that sports thing again) when you can recognize an idea and show how that idea got put to work in ways that served customers, grew revenues, created jobs, built communities, and changed the world.

Recognition opens the door; sincerity and implementation seal the deal. Creating organizational cultures that put people and ideas to work on matters of substance in ways that drive results is key. It’s key to making people, teams, and entire organizations feel important. It’s key to engaging the whole person.

I’m a child of what Tom Brokaw has called “the greatest generation.” One of the characteristics that makes this generation great is its quiet humility. It’s hard, even today, to get those that are still with us to talk about what they did. Make no mistake, they literally saved freedom. But, when these heroes talk, they don’t talk about Iwo Jima or Utah Beach as an opportunity.

They talk about what they did. They talk about surviving, having a buddy’s back, looking death and hell in the face, and coming out of a trench to charge forward. And they talk about winning. They didn’t go to war to try; they went to war to win. And they did. And, even if they’re too humble to admit it, they ought to feel important. They won. We won. Freedom won. And they’re damn important—to us and to history.

As a leader, it’s my job to create an environment where people can feel important, where they can feel part of something bigger than just themselves, where they can feel like they’re not just being heard but that what we’re hearing we’re trying and doing. And they need to know that in that trying, we’re changing the world.

Watch what happens to the energy in your organization when this culture of “feeling important” takes hold. Watch how the ideas multiply, the synergy swells, and the input soars.

Everyone knew that kid in second grade who constantly put her hand up because she knew she had the answer. If she found a teacher who’d keep calling on her rather than one that told her to put her hand down and let others participate, she flourished. If she felt shut down she did exactly that: she would shut down. She would realize that always having the answer was not “cool.” And when she realized that having all the answers was not “cool,” something very precious was lost.

Get your people raising their hands. Let them all answer. Take it all in. Sort through the answers for quality, of course, but wherever possible, put as much of it to work as you can. Because every idea that goes to work is tied to a person who offered it up in the first place. And, when people see their ideas take flight, they rise up with them. There’s no better example, in leadership, of an organization “rising up on eagle’s wings”—where its people and ideas are important and where ideas take flight.

The Need for Variety

Charles Dickens was a brilliant writer. He has, perhaps more than any other writer in the English language, captured the mood of his times. Substantial to both Dickens’s writing and the English world of the mid- to late nineteenth century was the rise of industry—with all the blessings and curses that entailed.

When Dickens describes the workhouse, the laundry, the factory, or the orphanage of his day, he is painting a vivid picture of what it meant to live, eat, drink, sleep, and suffer the realities of low-paying, soul-grinding menial labor.

Years later, in his seminal film Modern Times, Charlie Chaplin turned Dickens’s idea into the metaphor of the little man caught up in the industrial machine.

I’m not suggesting that the Industrial Revolution was a bad thing. (It was Marx—Karl, not Groucho—who said that.) In fact, I think that the Industrial Revolution played a major—if not the primary—role in bringing the world the standard of living many enjoy today.

But one thing factory work never brought was variety. Whether you were running fabric through a sewing machine, putting steel blanks in a stamping press, or stacking crate after crate on a loading dock, you were engaged in mundane, mind-numbing labor. And the hours were long; at the end of a day or week doing that kind of work you were left with precious little time for family, friends, or entertainment.

That life simply was not meeting the human need over time. And that’s why unions were of such importance; among other things, they helped the average laborer, industrialized production, and changed the length of the workday and workweek, creating something still very rare in much of the world: leisure time.

What did we do with our leisure time? We pursued variety. The global changes in lifestyle that leisure time created can be summed up in a simple comparison to Saturday morning.

In some households, Saturday morning is an opportunity to sleep in and recover from the week’s exertions. In others it’s a “get up early and get the chores done so we can go to town” day. In still others, it’s a chaotic chase after soccer practice, piano lessons, dance recitals, and the multitude of other activities that define so many young families and their pursuit of generational variety. Some garden, some run, some shop, some read, some work, and some play. And some just dream. But in any given town, on any given Saturday morning, what you’re seeing is variety at work.

Variety makes people happy; it makes them smile. In the workplace, variety can make them smile Monday through Friday as much as it does on Saturday, which is why a business leader ought to care. Give your people variety and they’ll smile more, and they’ll work better; they’ll be more hopeful and uplifted and feel less hopeless and downhearted.

Some jobs, of course, require repetition. We still sew shirts, make parts, and load trucks. But we’re finding ways to do this in a more engaging way. In some cases we’ve put robots to work on the most mind-numbing tasks. In others we engage concepts like job sharing, assignment rotation, and swing shifts to make sure no one feels trapped in a job or career.

We live in a society where we get opportunities to try new things, test our talents, change jobs, move around, and pursue—not always with perfect success—a number of things we think we might enjoy. This opportunity to seek variety in career as well as in life seems so much a part of life today we can forget that it’s a fairly modern phenomenon.

There are many things that typify a modern, millennial corporation. There are things that make Apple obviously Apple and not a tweaked form of IBM. And one of those things that Apple, Google, Facebook, Twitter, and so many other “top of mind” organizations share is their understanding of the importance of providing variety to their employees.

If you want to send Gen Xers or “millennials” running in the opposite direction, stick them in a cubicle, tell them to be there at exactly 8:00 a.m. and not leave one second before 5:00 p.m., and suggest that they take their Ritalin, manage their energy, and get down to the work of stacking ones and zeros like their grandparents stacked cases on the loading dock. It’s no longer tolerated. The Patrick Henrys of our century cry out “Give me variety, or give me my severance, ’cause I’m outta here!”

As a leader of a twenty-first-century organization your job is simple: if you want to attract, engage, and keep talented people you better be bringing a big bowl of variety. How do you do this? You get to know those around you. You ask them questions. You take the time to discover what type of variety they need in order to be wholly and creatively engaged.

Ask those around you:

• Are there unmet needs and opportunities that we are not pursuing?

• What do you think we could do in order to make a greater contribution?

• What do you like doing?

• What opportunities exist here that you are excited about? What are we lacking?

• What capabilities do you have that could be developed and utilized?

• What do you like best about your job? What would make it better?

Management assumes that people should be grateful to have a job—period. Leadership, on the other hand, acknowledges that you want to have more than an employee’s back: you want his or her heart, too; you want the whole person. But you’ll never understand what employees need—what variety needs are not being met—unless you first take the time to ask.