10

Study YouTube Success Stories

Although it is useful to measure views and ratings, how many of these outputs do you need to make the cash register ring? In this chapter, we'll study four YouTube success stories to learn how organizations have used video marketing to generate measurable outcomes. And I'll interview the key individuals who were willing and able to tell me more about their YouTube success stories.

- Chapter Contents:

- The Story behind the Story

- Deliver 700 Percent Increase in Sales: Will It Blend?

- Win the Presidency of the United States: Barack Obama

- Increase Sales of DVDs 23,000 Percent: Monty Python

- Generate $2.1 Million in Sales: PiperSport Launch

The Story behind the Story

I learned the difference between measuring outputs and outcomes over 20 years ago. Back in 1986, I became the director of corporate communications at Lotus Development Corporation. Actually, I was the company's 13th director of corporate communications, and that was when Lotus was only four and a half years old.

After my first month on the job, I took a very thick report on about 700 magazine and newspaper clippings that we'd generated, walked down the short hall to Jim Manzi's office (he was the chairman, president, and CEO), and casually dropped it on his desk.

My clipping report measured PR success in advertising value equivalency (AVE), which is calculated by measuring the column inches (in the case of print) or seconds (in the case of broadcast media) and multiplying these figures by the respective medium's advertising rates (per inch or per second). The resulting number was what it would have cost Lotus to place advertisements of that size or duration in those media.

But Manzi took a quick look and said, “Jarboe, these are just little pieces of paper. If I could deposit them in a bank, they'd be worth something. So, until you can measure the value of PR in cold, hard cash, don't waste my time with these so-called reports.”

Although I'd worked in high-tech public relations at Wang Laboratories, Stratus Computer, and Data General for five years before joining Lotus, I'd never encountered this lack of faith in PR before. But then I'd never worked for a CEO who was a former journalist as well as a former McKinsey consultant before.

And I had to admit, Manzi was right. He was focused on outcomes.

Around that time, my father was the director of marketing at Oldsmobile. His ad agency, Leo Burnett, had created the memorable TV commercial, “It's not your father's Oldsmobile.”

The folks at Leo Burnett were measuring the success of their ad campaign in gross rating points (GRPs), which represents the percentage of the target audience reached by an advertisement. If the advertisement appears more than once, the GRP figure represents the sum of each individual GRP. In the case of a TV commercial that is aired five times reaching 80 percent of the target audience, it would have 400 GRPs = 5 × 80%.

But sales of Oldsmobiles were falling from 1.2 million in 1986 to 800,000 in 1988 and then to under 600,000 in 1990. At one point, my dad asked his ad agency, “How many GRPs do we need to sell a car?”

My dad was asking the right question. He was focused on outcomes.

But the folks at Leo Burnett were focused on outputs. And with 20/20 hindsight, it's now clear the ad campaign was “unselling” Oldsmobiles every year it ran by informing older customers the brand wasn't targeted at them anymore and reminding younger prospects the brand had been driven by old fogies for a generation. This had a negative impact on the brand preference of Olds.

So, as I started writing this book, I also started looking for case studies of video marketing campaigns that did more than create lots of views and generate measurable outputs. I looked for YouTube success stories about creating a positive impact on brand preference and generating measurable outcomes.

And then, like the little girl in Figure 10.1, I also interviewed the key individuals who were willing and able to answer the question, “And what's the story behind the story?”

Figure 10.1 “And what's the story behind the story?” (Cartoon by Arnie Levin in The New Yorker, February 8, 1993.)

Here is what I learned from George Wright, Arun Chaudhary, John Goldstone, and Michael Kolowich about Will It Blend?, the Barack Obama 2008 presidential campaign, Monty Python's channel, and the PiperSport launch.

Deliver 700 Percent Increase in Sales: Will It Blend?

Let me start by telling the story of Blendtec, a division of K-TEC that makes high-performing, durable blenders for commercial use and a newer line of home appliances. Although you may not have heard of this small, Utah-based manufacturer, there's a good chance you've had a smoothie, cappuccino, milkshake, or other frozen drink made with a Blendtec blender.

Tom Dickson, the company founder, describes himself as a “geek.” And Kate Klonick of Esquire described him as “an otherwise bland grandfatherly-type from Utah” in an article on May 3, 2007. In other words, the star of Blendtec's videos isn't as exciting and dynamic as Barack Obama, whom we'll look at later in this chapter.

![]() Note: Brad O'Farrell, the technical editor of this book, thinks the star of the videos isn't Dickson, it's the Total Blender. So, maybe Blendtec's videos are as exciting and dynamic as “no-drama Obama.”

Note: Brad O'Farrell, the technical editor of this book, thinks the star of the videos isn't Dickson, it's the Total Blender. So, maybe Blendtec's videos are as exciting and dynamic as “no-drama Obama.”

George Wright, Blendtec's first director of sales and marketing, created a YouTube and video marketing campaign called “Will It Blend?” Wearing the white lab coat and safety glasses, Dickson takes everything but the kitchen sink, sticks it in a blender, and says, “Will it blend? That is the question.” While the item is blended, he smiles and waits for the process to end. When it does, he empties out the contents, provides a warning not to breathe in the item they just blended (“iPod smoke, don't breathe this!”) and the subtitle “Yes, it blends!” appears. In other words, Blendtec's video content isn't as compelling as the classic comedy of Monty Python, which we'll talk about later in this chapter.

When Blendtec hired Wright in January 2006, the company relied on demonstrations at trade shows and word-of-mouth referrals. On October 30, 2006, Wright created Blendtec's YouTube channel and spent $50 creating the first five “Will It Blend?” videos. He bought a white lab coat, the URL, and a selection of items to be blended, including marbles, a rake, a Big Mac Extra Value Meal, a “cochicken” (12 oz. can of Coke and half a rotisserie chicken), and some ice. In other words, Wright had a bare-bones budget.

“Will It Blend?” has since been called “the best viral marketing campaign ever.” It's been featured on the Today show, The Tonight Show, and The History Channel (now called History).

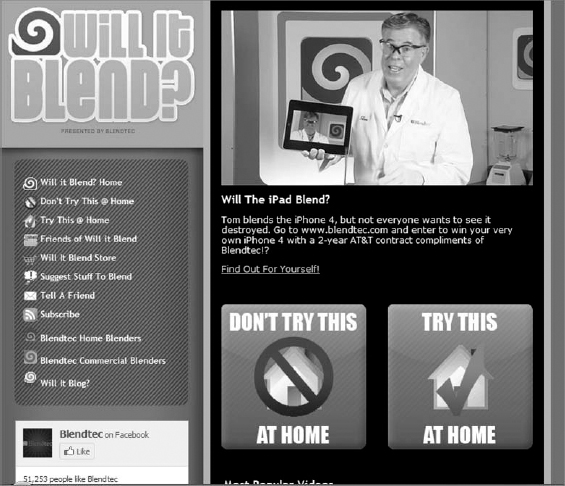

The 101 videos on Blendtec's channel on YouTube (Figure 10.2) have more than 135.4 million views, making it the #60 most viewed of all time in the Directors category. The channel also has over 323,000 subscribers, making it the #33 most subscribed to of all time in the Directors category.

And as Figure 10.3 illustrates, this doesn't count some of the views on or subscribers to the official Will It Blend? site, which has additional Blendtec videos that don't use the YouTube player(www.willitblend.com).

Figure 10.2 The Will It Blend? channel

Figure 10.3 The Will It Blend? site

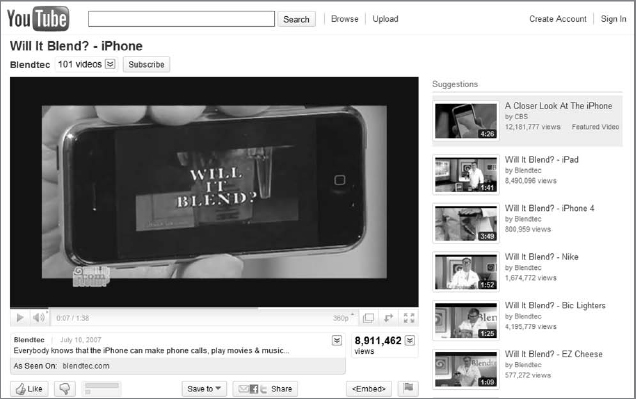

As Figure 10.4 illustrates, the most viewed and most discussed video in the series, “Will it Blend? - iPhone,” has more than 8.9 million views. It also has more than 23,400 ratings and almost 12,200 text comments and has been favorited over 22,500 times.

Figure 10.4 “Will It Blend?-iPhone”

I first met Wright on October 3, 2008, at the Digital PR Next Practices Summit in New York City. At the PR News conference, he talked about building community and reputation online with social media tools, and I discussed improving your search engine marketing and PR.

I'd already seen “Will it Blend? - iPhone.” And I'd already written, “Unless you are one of the Blendtec guys, don't try using their humorous viral marketing techniques at home.”

But, before Wright spoke, I still wasn't sure if he had been lucky or good. Slide 3 of his presentation outlined the critical components of his “Will it Blend?” viral marketing campaign. It clearly showed me that Wright was good. Here's a quick idea of what he said about each critical component:

Entertaining“A viral video doesn't have to be funny, but it has to be worth watching! You gotta check this out! That's the test.”

Business objective“’Will it Blend?' generates revenue. Nike has offered to pay us money to blend one of their new shoes.”

Honesty in claims“When we said we'd blended neodymium magnets, we got email telling us they were ceramic magnets.”

Keep it real“We try to be ourselves and our videos are not overproduced. We try to be a little bit edgy, but not too slick.”

Interactivity“People suggest things to blend, like the new iPhone. They aren't just viewers; they're engaged.”

Simple user subscription“We have more than 200,000 subscriptions to our YouTube channel and our own ’Will it Blend?' website.”

Then Wright said, “This new form of marketing has delivered a 700 percent increase in sales for Blendtec.” During the network break between our presentations, I asked Wright if he would be interested in providing one of the case studies for this book. And he asked me, “Have you read the profile on Blendtec in Michael Miller's new book, YouTube for Business?” (YouTube for Business was published by Que in August 2008.)

As a matter of fact, I had read the book. But I wanted to interview Wright a year after Miller had, hoping that there would be new developments or more details to share with my readers. Wright agreed to be interviewed six months later and then headed out to the lobby to blend a wooden rake handle for all the other conference attendees.

In the spring of 2009, I called Wright at his office in West Orem, Utah. As I had hoped, there were new developments and more details for us to talk about. At that point, Wright was Blendtec's vice president of marketing and sales.

And as Figure 10.5 illustrates, Blendtec has used YouTube and video marketing in the past year to transform itself from being focused on business-to-business (B2B) to being focused business-to-consumer (B2C) sales.

Q&A with George Wright, Vice President of Marketing and Sales, Blendtec

Here are my questions and his answers.

Jarboe: What's your background? What did you do before joining Blendtec? How did you first get the idea for “Will It Blend?”

Wright: My background is in heavy industry. Before joining Blendtec, I handled PR at a steel mill and marcom for a major pump and valve manufacturer. My budget was huge at these other companies. But that was different at Blendtec, which had a wonder product but no marketing. However, we did have a video producer and equipment already to create instructional videos for our commercial customers. Then I happened upon owner Tom Dickson feeding a 2×2-inch wooden board into a commercial blender as part of a destructive test and found it fascinating. I thought that others might get a kick out of watching the process, and the idea for creating a video was born. I wrote a marketing strategy entitled “Blending Marbles.” Then, as I said last October, I spent $50. The most expensive things I bought were half a rotisserie chicken and 12 ounces of Coke. At the time, I said, “Dang, this is good cochicken. This is the best I ever tasted.” But then a month later, we transmogrified half a dozen oysters in the whole shell. It was better than anything else (Figure 10.6).

Figure 10.6 “Will It Blend?-Oysters”

Jarboe: Who is your target audience? Is it opinion leaders in the YouTube community or customers who also watch online video? Has your target audience changed from when the channel was launched to now?

Wright: Our target audiences were existing customers, potential customers, and employees. We needed to explain complicated pieces of equipment to both B2B and B2C market segments. Although our target audience now includes homemakers as well as our wholesale dealer network and key accounts, all these people are already interested in our product.

Jarboe:Do you optimize your videos for YouTube? Are there search terms that you put in the title, description, and tags of your videos on YouTube? Are there search terms that you use to optimize videos for Google?

Wright: We have optimized around our product. We created the “Will It Blend?” brand name. But blending an iPod was also part of our search engine optimization strategy (Figure 10.7).

Figure 10.7 “Will It Blend?-iPod”

Jarboe: What is the most compelling video content on Blendtec's channel? Is it one of the most viewed or most discussed videos? Is it your playlist?

Wright: I'm always blown away by “Will It Blend? - Marbles.” That was the question I asked in my original marketing strategy. We put a bag of 50 marbles into a Blendtec blender. And yes, it blends! Blending a dozen glow sticks was also fun. When we turned the lights off for effect, our 12-hour lantern was engaging. For live blends, we always blend a rake with a wooden handle because it is visual from a distance. Blending a baseball was funny. But some of the best videos we have done to date are in our playlist (Figure 10.8).

Jarboe: What is your channel strategy? How much effort is focused on Blendtec's channel on YouTube versus www.willitblend.com? Has this changed since the channel was launched? Will it change going forward?

Wright: We are focused on our own Will It Blend? website, which we control. The analytics are better. And our website gets more views than our YouTube channel. Now, YouTube is a great place to reach new people. But, the website has links to our e-commerce website, so they [customers] can buy our product.

Jarboe: In addition to creating compelling video content, have you engaged in any outreach effort with the YouTube community or bloggers? Do you give opinion leaders a “heads-up” when a new video is uploaded?

Wright: We have more than 200,000 subscribers. They automatically get a “heads-up” whenever we upload a new video. Although we did let the folks at Nike know when we decided to remix their Air Max 90 Current (Figure 10.9). But they'd asked us to do that.

Jarboe: What production challenges have you faced and overcome? Are there any tips or tools that you used to get videos uploaded?

Wright: Keep it real, keep it short, and get to the point. “Will It Blend?” That's as complicated as it gets. On blending day, we won't let Tom know what we're blending. That keeps it real.

Jarboe: Have you taken advantage of any video advertising opportunities? Have you used Yahoo! Video ads, InVideo Ads, contests, or other high-profile placements?

Wright: We haven't taken out any ads. We did put up a billboard on the side of our factory, but YouTube is a social channel. So, we let it work its magic.

Figure 10.9 “Will It Blend?-Nike”

Jarboe: How do you measure your video campaign? Do you use YouTube Insight, TubeMogul, or other analytics for online video? Do you use web analytics on www.willitblend.com? What feedback have these tools given you that may have led you to change anything you were doing?

wright: It's hard to pay for fancy analytics when you only spend $50 to start with. So, on our Will It Blend? website, we use Google Analytics because it's free.

Jarboe: I've already got the Will It Blend - The First 50 Videos DVD. What else should I get?

Wright: You could get a Will It Blend? T-shirt, which you can wear while pondering life's important questions. What is the purpose of life? What is the airspeed velocity of an unladen swallow? And, of course, Will It Blend?

In March 2010, Wright became executive VP of marketing at Traeger Wood Pellet Grills. He emailed me to say, “Today is my last day at Blendtec… I have accepted an amazing new opportunity to help build a fun company that manufactures wood pellet BBQ grills. If you have never tasted food cooked/smoked on a Traeger Grill, you are missing out!”

He added, “Leaving Blendtec was a difficult decision. Creating the Will It Blend? video series was a complete blast and I will certainly miss it. I will continue to provide keynote addresses on social media using the inside story of Blendtec and will actively work to add Traeger success to the continuing story.”

Win the Presidency of the United States: Barack Obama

On November 4, 2008, at 9:27 p.m., Barack Obama won the state of Ohio and the outcome of the presidential election became crystal clear. Sean Quinn of FiveThirtyEight.com observed, “That's the ballgame folks. He will be the next president of the United States. Barack Obama will be the next president of the United States.”

Today, the whole world knows that Obama won the Democratic Party's nomination after a close campaign against Hillary Rodham Clinton in the 2008 presidential primaries and caucuses. Obama then defeated Republican candidate John McCain in the 2008 general election to become the first African-American elected president. And we also know that the 1,800 videos on BarackObamadotcom's channel on YouTube had been viewed over 110 million times as of November 4, 2008. But did the videos impact what happened next? Obama won 69.5 million popular votes and 365 electoral votes.

To understand the impact of YouTube and video marketing on candidate preference and election outcomes, the person I wanted to interview for this book was Arun Chaudhary. He's been called “Obama's auteur” by Aswini Anburajan of National Journal Magazine (April 19, 2008) and “Obama's video guru” by Michael Learmonth of Silicon Alley Insider (July 17, 2008).

Chaudhary's official title on the campaign was new media road director of Obama for America (OFA). Today, he is the White House videographer (Figure 10.10).

Figure 10.10 “Online Video Production Best Practices-A Discussion with Arun Chaudhary from Obama for America”

Barack Obama started using YouTube and video marketing even before officially announcing his candidacy for the presidency of the United States on February 10, 2007.

On January 16, 2007, Obama announced via video on YouTube and his website that he had formed a presidential exploratory committee. As Figure 10.11 illustrates, the 3-minute, 7-second video has more than 1.9 million views.

Figure 10.11 “Barack Obama: My Plans for 2008”

The video also has over 11,100 ratings and almost 4,500 comments. It has also been favorited 1,360 times.

The fact that a preannouncement video could create such an impact indicates that an “invisible caucus” may have been held a month before the “invisible primary.”

What's an invisible caucus? And what is an invisible primary?

As Linda Feldmann of the Christian Science Monitor reported on February 26, 2007, there was a lot of media buzz about “what's come to be known as the ’invisible primary'—the early jockeying for money, top campaign staff, and high-profile endorsements that winnow the presidential field long before any caucuses or primaries are held.”

So, I'm calling the early jockeying for opinion leaders in YouTube's news and politics category an “invisible caucus.” And it is worth asking, Did winning it help a former community organizer's presidential campaign take off?

If there is an answer to this question, it's buried in the list of close to 73,000 friends and more than 194,000 subscribers to BarackObamadotcom's channel.

Although you can find out when someone made a campaign donation or public endorsement, YouTube doesn't give you the ability to see the exact date they became a friend or subscriber to a YouTube channel. Yes, the earliest friends and subscribers are on the last page, but no, I don't have the time to go through 73,000 friends and 194,000 subscribers. So, like the chicken and the egg, let's just say we don't know which came first.

We do know that Chaudhary, a 32-year-old New York University film-school professor, took a leave of absence in the summer of 2007 to work for OFA.

In his April 19, 2008, cover story, “Obama's Auteur,” Anburajan wrote, “Before Obama, Chaudhary—the son of an immigrant Indian father and a Jewish mother, both scientists—had tried to interest New York-area politicians in his scripts for political ads and Internet videos but to no avail. Then came the senator from Illinois.”

Chaudhary lobbied hard for a position in the Obama campaign. He even interrupted both his wedding rehearsal dinner and his wedding day in May 2007 to sell himself to Joe Rospars, OFA's director of new media.

Rospars decided to hire a pro with real film experience to add something fresh to Obama's YouTube and video marketing campaign. “There's a lot of open space to be creative in a campaign and people don't take advantage of it,” Rospars told Anburajan.

So Chaudhary became the full-time $40,000-a-year director of field production for the campaign, crisscrossing the country alongside the candidate with two other videographers, making videos that sought to pull supporters into the campaign by letting them peer through his lens.

“Why do you need to see someone with a mike in their hand telling you what Barack Obama said today when you can see for yourself what Barack Obama said today?” Chaudhary told Anburajan.

Chaudhary also told Anburajan about a Chinese-American rapper named Jin the Emcee, who decided to join the Obama campaign after spending a night viewing all of the candidate's campaign videos on his computer.

This provides at least anecdotal evidence for my “invisible caucus” theory.

Of course, the campaign was also being waged offline as well as online. On November 21, 2007, Obama announced that Oprah Winfrey would be campaigning for him. As word spread that Oprah's first appearance would be in Iowa, polls released in early December revealed Obama taking the lead in that critical state. Although celebrity endorsements typically have little effect on voter opinions, the Oprah-Obama tour drew record-setting crowds in Iowa and dominated political news headlines.

On January 3, 2008, Obama won the Iowa Democratic caucus, the first contest in the Democratic nomination season. Obama had the support of 37.6 percent of Iowa's delegates, compared to 29.7 percent for John Edwards and 29.5 percent for Hillary Clinton.

In his remarks to his followers that evening, he said, “On this January night, at this defining moment in history, you have done what the cynics said we couldn't do.” He added that in the future, Americans will look back on the 2008 Iowa caucuses and say, “This is the moment when it all began.”

This brings us to Obama's “Iowa Caucus Victory Speech” on January 3, 2008. As Figure 11.4 illustrates, the 14-minute, 7-second video has close to 2.4 million views; it also had over 9,400 ratings.

This was the #2 most discussed video on BarackObamadotcom's channel, with more than 5,300 text comments as of April 2009. It had also been favorited more than 1,600 times.

Although news and political junkies could watch the entire speech live at 11:04 p.m. EST, opinion leaders could also share the entire speech with their followers the following day. This means the medium enabled the YouTube community to get a more complete message than you could get from the typical “sound bite,” which had dominated political discourse for more than 40 years.

Figure 10.12 “Iowa Caucus Victory Speech”

Now, this didn't shorten the Democratic nomination process, which continued until June 7, 2008. But it did change it.

On July 16, 2008, frog design, Fast Company, and NYU's Tisch Interactive Telecommunications Program hosted an event at NYU entitled “Obama and Politics 2.0: Documenting History in Real-Time.” It featured a conversation with Chaudhary and Ellen McGirt, a senior writer for Fast Company.

The following day, Learmonth posted a story on Silicon Alley Insider about the event entitled “Obama's Video Guru Speaks: How We Owned the YouTube Primary.” According to Chaudhary, Obama's organization took online video seriously from the outset, which put them ahead of previous efforts. The Clinton campaign would have had just one staffer videotaping an event; Obama's had between two and four people shooting, editing, and posting video in order to get multiple camera angles. They were fast in getting video posted (as fast as 19 minutes from shoot to post) and fast in alerting voters when new video was up. Wrote Learmonth:

Obama's YouTube and web site metrics show that his online viewers aren't pups. The average viewer is 45 to 55 years old, Chaudhary said, a fact he found “shocking.” And while Chaudhary made plenty of humorous clips, they weren't the most popular. Invariably the videos that got the most views were long clips of speeches, unscripted moments, or, say, an appearance on “Ellen” or “Oprah.” The viewing reflects a hunger not to be entertained, but to know something about the candidate.

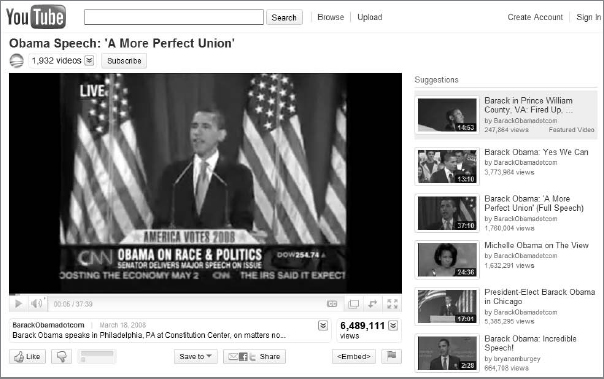

This brings us to the “Obama Speech: ’A More Perfect Union.'” As Figure 10.13 illustrates, the 37-minute, 39-second video has almost 6.5 million views.

Figure 10.13 “Obama Speech: ‘A More Perfect Union’”

This video also has 29,300 ratings, generated more than 10,000 comments, and was favorited 3,225 times.

Obama spoke in Philadelphia on March 18, 2008 at the National Constitution Center on matters not just of race and recent remarks made by the Reverend Jeremiah Wright but of the fundamental path by which America can work together to pursue a better future.

Just nine days later, the Pew Research Center called the speech “arguably the biggest political event of the campaign so far,” noting that 85 percent of Americans said they had heard at least a little about the speech and that 54 percent said they heard a lot about it.

On June 15, 2008, a report by the Pew Internet & American Life Project found 35 percent of Americans said they had watched online political videos—a figure that nearly tripled the reading the Pew Internet Project got in the 2004 race.

The report also found that Obama supporters outpaced McCain supporters in their usage of online video.

Aaron Smith, a research specialists, and Lee Rainie, director of the Pew Internet Project, said, “The punch-counterpunch rhythms of the campaign are now usually played out online in emails and videos rather than in faxed press releases and 30-second ads.”

So, what impact did online video have on the outcome of the 2008 presidential election?

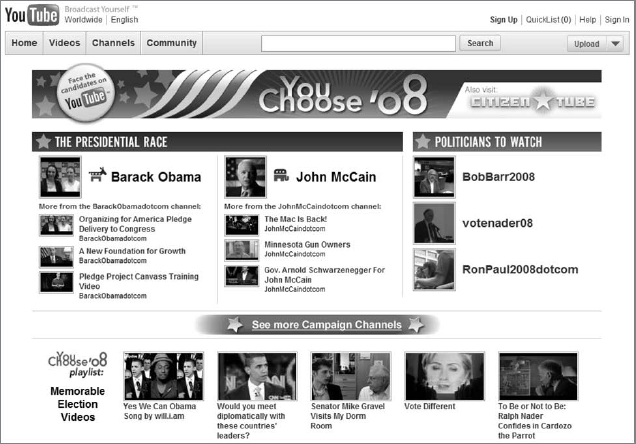

BarackObamadotcom's channel on YouTube had been launched on September 5, 2006 (Figure 10.14). It had just over 113,000 subscribers and more than 18 million channel views as of November 1, 2008. And the 1,760 videos on the channel had 93,929,314 total upload views.

JohnMcCaindotcom's channel on YouTube had been launched on February 23, 2007. It had 28,000 subscribers and over 2 million channel views on that date. And the 327 videos on the channel had over 24 million views all time.

Overall, Obama's videos on YouTube had almost a 4-to-1 lead over McCain's videos in total views and a 9-to-1 lead in channel views the Saturday before Tuesday's presidential election.

In the previous month, Obama's videos had more than 16 million views compared to under 4 million views for McCain's. In the previous week, Obama's videos had over 4 million views compared to 633,000 views for McCain's.

So what impact did YouTube and video marketing have on candidate preference and election outcomes?

On November 7, 2008, Claire Cain Miller posted a story entitled “How Obama's Internet Campaign Changed Politics” on the Bits blog at NYTimes.com. In it, she quoted Joe Trippi, who had run Howard Dean's campaign in 2004.

Trippi said Obama's campaign took advantage of YouTube for free advertising and Trippi argued that those videos were more effective than television ads because viewers chose to watch them or received them from a friend instead of having their television shows interrupted.

“The campaign's official stuff they created for YouTube was watched for 14.5 million hours,” said Trippi. “To buy 14.5 million hours on broadcast TV is $47 million.”

On November 14, 2008, Jose Antonio Vargas wrote an online column for the Washington Post entitled “The YouTube Presidency.” In it, he quoted Steve Grove, head of news and politics at YouTube.

Grove said, “The Obama team has written the playbook on how to use YouTube for political campaigns. Not only have they achieved impressive mass—uploading over 1,800 videos that have been viewed over 110 million times total—but they've also used video to cultivate a sense of community amongst supporters.”

On April 15, 2009, the Pew Internet & American Life Project reported on the Internet's role in campaign 2008. Here are the findings of its postelection survey of 2,254 adults conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates International from November 20 to December 4, 2008:

- Forty-four percent of online Obama voters had watched video online from a campaign or news organization, compared to 39 percent of online McCain voters.

- Thirty-nine percent of online Obama voters had watched video online that did not come from a campaign or news organization, compared to 35 percent of online McCain voters.

- Twenty-one percent of online Obama voters shared photos, video, or audio files online related to the campaign or election, compared to 16 percent of McCain voters.

Aaron Smith, a research analyst with the Pew Internet Project, said in the report, “Due to demographic differences between the two parties, McCain voters were actually more likely than Obama voters to go online in the first place. However, online Obama supporters were generally more engaged in the online political process than online McCain supporters.”

He added, “Among Internet users, Obama voters were more likely to share online political content with others, sign up for updates about the election, donate money to a candidate online, set up political news alerts, and sign up online for volunteer activities related to the campaign. Online Obama voters were also out in front when it came to posting their own original political content online—26 percent of wired Obama voters did this, compared with 15 percent of online McCain supporters.”

Smith also observed, “In 2008, nearly one in five Internet users posted their thoughts, comments, or questions about the campaign on a website, blog, social networking site, or other online forum.” He called this group “the online political participatory class.” I'd call them opinion leaders. They helped Obama win the presidency of the United States.

Q&A with Arun Chaudhary, New Media Road Director of Obama for America (OFA)

In spring 2009, I got my opportunity to ask Chaudhary questions about OFA's YouTube and video marketing campaign. We conducted the interview via email.

Jarboe: You took leave from NYU to become Barack Obama's director of video field production. How did you first get involved in the campaign?

Chaudhary: An old friend of mine, Kate Albright-Hanna, had taken the position of director of video for the OFA New Media Department. She thought that I might be a good fit to join the team, which was lucky for me because as a film academic and primarily a maker of fiction, I may not have looked like an obvious choice on paper. Video production on the campaign developed very organically as according to need more than by grand design, so the separation of the “Road Team,” which I led as the new media road director, wasn't something that was anticipated when I joined the campaign. I was more of the short, funny, creative things guy.

Jarboe: After two years on the campaign trail, you've posted more than 1,000 videos on the BarackObama.com website and on YouTube. What are your most memorable ones?

Chaudhary: There are two videos that always stand out to me.

One I shot on the eve of the Iowa Caucuses (Figure 10.15). President (then Senator) Obama wanted to visit a caucus location, so we went about 45 minutes north of Des Moines to Ankeny, Iowa, not taking any press with us. It was a magic moment, not a single vote of any kind had been cast in the election and we had been campaigning for almost a year, hoping and trusting the American people were hearing the campaign's message. The air was full of anticipation, and when Barack walked in and everyone flocked to him and said they were caucusing for him, we knew that something serious had begun. The little video we made of this visit was posted to YouTube within minutes of it happening but was drowned out in all the attention of the Iowa victory speech that was posted almost immediately afterward. There is a lesson in there somewhere.

Figure 10.15 “Caucus Night: Barack in Ankeny”

The second video would be our online response to the Clinton campaign's “3 a.m. Girl” ad (Figure 10.16). Senator Clinton had made a political ad about a 3 a.m. phone call that occurred “while your children are asleep.” In a strange turn of events, the child in the stock footage the ad used had grown up to be an Obama supporter. The young woman was actually an Obama precinct captain in Washington State. I went to Tacoma to see her, and within 20 hours, travel included, we had a response piece up in YouTube. It was really fun and interesting to do it as a web piece because we had screen time enough to really play around with the material. The final product was as much of a deconstructing of the typical negative ad as it was the young girl's story.

Jarboe: Who was your target audience? Was it opinion leaders in the YouTube community or political activists who also watched online video? Did your target audience change from 2007 to 2008 or from the primaries/caucuses to the general election?

Figure 10.16 “Hillary's ‘3 A.M. ad’ Girl Doesn't Approve of that Message”

Chaudhary: Our target audience was voters, all kinds of voters. While YouTube community folks and political activists were probably vocal commenters on our work, I don't think it would make sense to think of them as a target audience. We wanted to appeal to a wide variety of folks. When you have a candidate as exciting and dynamic as Barack Obama was, the most important thing you can do is get him in front of as many people as possible. We used to say the YouTube or live stream hits of his speeches were like adding thousands of extra seats in the room. Especially in the early states, the sort of people you want to watch an event are folks who couldn't physically make it for some reason. Rather than fishing for viral success, you'd rather have real prospective voters see your candidate make his or her case.

Jarboe: Did you optimize your videos for YouTube? Were there search terms that you put in your title, description, and tags of your videos on YouTube? Were there search terms that were used to optimize videos for Google?

Chaudhary: We tried to be very specific. Location and date of the speech was very important because you really hope that folks who weren't physically able to make the rally are able to find the footage. Topic is very important as well, because a lot of folks looking for political content online are hoping to find answers to their specific questions (what is the candidate's position on health care?) in that way; the candidate's websites are very much a modern update of campaign literature, or maybe even a bit like the voting guides various groups used to publish close to election times (Figure 10.17). You really can't be too specific with your titling, though of course there are only so many words you can actually have in the title itself. I also think it's important to include information in the piece itself. With emerging technologies and when posting videos on many different platforms, you never quite know what will happen. One of the format rules for BarackObama.com that was designed and enforced by Kate Albright-Hanna was that the opening card for every video would be the date and location. I remember thinking that it was maybe a little too austere, but she was absolutely right. If you lived in Keokuk, Iowa, and a friend forwarded you a video link, the first thing you would see when you clicked on it would be November 20th, 2007, Keokuk, Iowa, and you would immediately know why it was relevant to you.

Figure 10.17 “Barack Obama on Health Care”

Jarboe: What was the most compelling video content of the campaign? Was it “Yes We Can - Barack Obama Music Video” or “Obama Speech: ’A More Perfect Union'”?

Chaudhary: I think I better leave the awarding of superlatives to folks who were the audiences of these movies, but between the two you mentioned, I would have to go with “A More Perfect Union.” The Will.i.am piece (which was not produced by the campaign; it was made by the artists themselves) was really great, and I think a lot of people found it very inspiring and accessible, but we had consistent calls from the public to put up speeches in their entirety. As time went on, we found that some of the effort of finding specific clips and producing them with cut shots was better spent trying to get entire speeches and town halls online. Folks really seemed to respond to being allowed to see the candidate unedited. In a sense they wanted to see the candidates in the raw and make their own decision, not to feel like they were being fed media. With a candidate as compelling as Barack Obama was, it made a lot of sense to let them see him in this manner. The more people actually saw him speak and heard his views, the more likely they were to vote for him. With a different candidate one might need to take a different strategy, but for us, Barack Obama was always the star; we were just the backup singers.

Jarboe: What was your channel strategy? How much effort was focused on BarackObamadotcom's channel on YouTube versus BarackObama.com/tv/? Did this change from 2007 to 2008 or from the primaries/caucuses to the general election?

Chaudhary: There was a change. As we began seeing that the strongest case we could make for Barack Obama was being made by Barack Obama himself, we spent more time and video resources on the road with the candidate. The team that I led, the Road Team, consisted of six folks who did all the videotaping, still photography, and blogging from the trail itself, putting up YouTube clips from every event, whether it be a speech, a town hall, or even a visit to a local diner.

There was another video team (the one led by Kate Albright-Hanna) who made video content from headquarters, often the more produced pieces. The YouTube channel ended up being dominated by material from the Road Team simply because of the huge volume of videos we produced, although everything was on it. BarackTV was curated by Kate Albright-Hanna (using a higher-quality player than YouTube) with an eye toward the more produced content (Figure 10.18). It was meant to be a complete viewing experience rather than campaign literature.

Figure 10.18 Organizing for America

Jarboe: In addition to creating compelling video content, did you engage in any outreach effort with the YouTube community or bloggers? Was there any effort to give opinion leaders a “heads-up” when a new video was uploaded?

Chaudhary: There was some effort put into blog outreach, mostly from the HQ side; I can't really speak to it, because I wasn't involved with it, nor was it something we thought about much on the road.

Jarboe: What production challenges did you face and overcome? Was video produced in the field but uploaded from headquarters? Are there any tips or tools that you used to get videos uploaded on a daily basis?

Chaudhary: The production challenges were immense. We would often arrive at events with about 10 minutes to go before a speech would start and need to set up our cameras and live-streaming computer as fast as we could. If everything went right, it was just about possible. Editing was just as challenging. The Road Team edited in the field on laptops and uploaded with aircards. On an airplane you can only upload to about 30,000 feet before losing all signal, so time was always of the essence. The watchword on our team was “workflow.” Because we were doing so many events and traveling so constantly, we had a lot of opportunity to improve the workflow; see what order things should be done in, what tasks the computer could handle doing at the same time, figure out how to fill what little time we had to its fullest. Redundancy also helped. Every Road Team member had a camera, a laptop, and an aircard. That way we weren't reliant on any one person to get the job done; we were all able to do what we needed to do. It was definitely a process. By the end of the campaign, it was taking us minutes to upload what was taking hours at the beginning. There was no magic formula, it was just experience. The thing about doing a process over and over and over is that eventually you get better. A tip I would definitely offer others is to always worry about the audio first; once you have that everything else is fixable. Bad video can seem like a choice while bad audio is always a mistake.

Jarboe: Did you take advantage of any video advertising opportunities?

Chaudhary: This isn't really anything I can speak to directly; Joe Rospars and our online ad guys Michael Organ and Andrew Bleeker did a lot of amazing things, even putting up Obama posters in video games, but it wasn't something the Road Team got involved with other than providing footage—something we did for the television folks as well.

Jarboe: How did you measure your video campaign? Did you use YouTube Insight, TubeMogul, or other analytics for online video? Did you use web analytics on BarackObama.com? What feedback did these tools give you that led you to change what you were doing?

Chaudhary: We did pay attention to the analytics. In fact, there was an entire section of the New Media Department devoted to analyzing all the data.

On a personal level, I was never quite sure how accurate the metrics of YouTube Insight or TubeMogul were, but I think it can show you some general trends and that can be quite useful. Seeing that folks would actually watch entire speeches and not just clips was very useful, especially as it is slightly counterintuitive. Also finding out that our core audience was much older than the 18–25 demographic was very interesting. According to the YouTube Insight tool, our main audience was 40 to 50, which is what you would expect from normal political media but not necessarily online. It has certainly reinforced my notion that online political video was essentially the modern replacement for the printed campaign guides of the past. I think a lot of folks went to all the websites to compare and contrast the candidates' views and make an informed decision.

Jarboe: I see President Obama using YouTube (Figure 10.19) as effectively as President Roosevelt used radio when it was still a new medium. How do you see President Obama's use of online video?

Chaudhary: Without getting into specifics, I will say that President Obama has said that he is committed to the idea of a more open, more transparent administration and that online video can certainly be an effective means to achieve that end.

Figure 10.19 Whitehouse's channel

So, did the Barack Obama 2008 presidential campaign use video marketing to generate measurable outcomes?

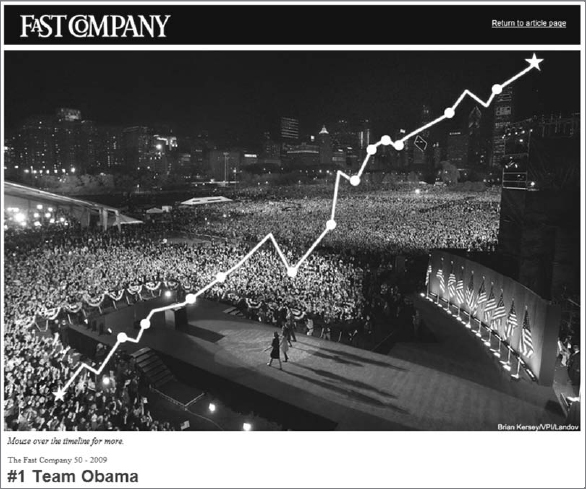

As Figure 10.20 illustrates, Fast Company named Obama's presidential campaign team #1 in the Fast Company 50 for 2009. The magazine said, “This year's most successful startup took a skinny kid with a funny name and turned him into the most powerful new national brand in a generation.”

Figure 10.20 The Fast Company 50-2009: #1 Team Obama

Fast Company said, “The team has become the envy of marketers both in and out of politics for proving, among other things, just how effective digital initiatives can be.” It added, “The community that elected Obama raised more money, held more events, made more phone calls, shared more videos, and offered more policy suggestions than any in history. It also delivered more votes.”

There's one additional lesson to learn from the former community organizer's presidential campaign. In Steve Garfield's book, Get Seen: Online Video Secrets to Building Your Business (Wiley, 2010), Thomas Gensemer, managing partner of Blue State Digital, shared his thoughts on how video played a role in the Obama campaign for president in 2008.

Gensemer said, “Some 11,000 videos were produced over the course of 22 months, fewer than 10 percent of them probably actually featured the candidate, fewer than 2 percent actually took time from the candidate.”

He added, “The story of (the campaign) was about people like you going to events with your video camera, or someone going with a clipboard to sign people up—that became the excitement around this campaign.”

Gensemer concluded, “It wasn't about technology. It was about a candidate and an inner circle who understood that one neighbor knocking on the next was more important than flooding the airwaves, and putting things in the mail, that was the essence of the campaign.”

Increase Sales of DVDs 23,000 Percent: Monty Python

“And now for something completely different.”

It's Monty Python, another group that has used YouTube and video marketing to generate measurable outcomes—yes, yes, the six comedians: Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin.

The group created Monty Python's Flying Circus. I saw their first show on the BBC when it aired on October 5, 1969. I was a student at the University of Edinburgh back then. Some of my favorite sketches are “Dead Parrot,” “The Spanish Inquisition,” and “The Ministry of Silly Walks.”

The Pythons went on to make such movies as Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), Monty Python's Life of Brian (1979), and Monty Python's The Meaning of Life (1983). And Idle wrote Monty Python's Spamalot. I bought a T-shirt at the musical that says, “I'm not dead yet.”

But I never expected to see the Pythons in this book until January 21, 2009. That was the fateful day the YouTube Blog mentioned, “When Monty Python launched their channel in November, not only did their YouTube videos shoot to the top of the most viewed lists, but their DVDs also quickly climbed to No. 2 on Amazon's Movies & TV bestsellers list, with increased sales of 23,000 percent.”

That was exactly the kind of success story that I knew you, the reader, would want to read. But, I didn't know how to contact Cleese, Gilliam, Idle, Jones, or Palin. (Chapman is deceased.)

So, I poked aimlessly about MontyPython's channel (shown in Figure 10.21) on YouTube hoping to find a way to connect with one of the comedians.

I have a YouTube account, so I could have sent them a message. But I thought that would make me look like just another fan of their sketch comedy.

Then, I discovered that, as Figure 10.22 illustrates, one of the most viewed videos on their channel was entitled “The Monty Python Channel on YouTube.” That didn't seem right.

Figure 10.21 The Monty Python Channel

Figure 10.22 “The Monty Python Channel on YouTube”

I watched the 2-minute-and-29-second video and then read the channel information box. One was a close imitation of the language and thoughts of the other. Based on my extensive research, I concluded that the Pythons had created the YouTube channel in November 2008 to stop YouTubers from ripping them off. Here's an edited transcript “lovingly ripped off” from their remarks:

For three years, you YouTubers have been ripping us off, taking tens of thousands of our videos and putting them on YouTube….

We know who you are….

We know where you live….

We could come after you in ways too horrible to mention….

But being the extraordinarily nice chaps we are, we've figured a better way to get our own back….

It's time for us to take matters into our own hands….

By launching our very own Monty Python channel on YouTube….

No more of those crap-quality videos you've been posting. We're giving you the real thing—high-quality videos delivered straight from our Monty Python vault….

What's more, we're taking your most viewed clips and uploading brand-new high-quality versions….

And what's even more, we're letting you see absolutely everything for free….

But we want something in return….

We want you to click on the links and buy our movies and TV shows….

Only this will soften our pain and disgust at being ripped off all these years.

As you can see in Figure 10.22, “The Monty Python Channel on YouTube” has almost 2.5 million views. It also has more than 6,000 ratings and over 2,500 text comments. In addition, it has been favorited more than 4,000 times and has generated 35 video responses.

Meanwhile, Aaron Zamost in Google Corporate Communications put me in touch with John Goldstone, who is Monty Python's producer. In fact, Goldstone has been collaborating with the Monty Python team since 1974.

I emailed Goldstone some questions and he promptly emailed me back some answers. His email included an image of the Python mascot, Mr. Gumby (Figure 10.23), so I knew it was authentic.

Figure 10.23 Monty Python's Mr. Gumby

Q&A with John Goldstone, Producer of Monty Python and the Holy Grail

Although I was tempted to ask at least one question that was “far too silly,” I didn't want to be stopped by a member of the “Anti-Silliness Patrol.” So, I asked Goldstone questions that were similar to the ones I'd asked Wright and Chaudhary.

Jarboe: What's your background? How did you first get involved in Monty Python's channel on YouTube?

Goldstone: I have been working with Monty Python over the last 35 years. I produced the three movies—Monty Python & the Holy Grail, Life of Brian, and The Meaning of Life—and because we were able to keep the copyright in the movies and the 45 episodes of Monty Python's Flying Circus, I was able, when DVD became the primary format for home entertainment, to revisit the movies and TV shows and give them a whole new life both technically and with a considerable amount of new content. As the power of DVD started to recede last year, it was time to review our digital strategy, and apart from initiating a program of making the titles available for digital download, we felt the time had come to deal with the “YouTube problem.” On the one hand, we were surprised at the number of clips that had been uploaded to YouTube in clear infringement of our copyright, and while we didn't want to be spoilsports, it was getting pretty much out of control and we could see no real benefit. So I arranged a trip to meet the YouTube guys on the Google campus in San Jose and discovered that they had a program that would enable us to have our own Monty Python channel on YouTube where we could put up clips from the movies and TV shows of far greater quality and order that might also encourage viewers to want to see whole movies or TV episodes via links to Amazon and iTunes and expand our Monty Python fan base.

Jarboe: Who was your target audience? Was it opinion leaders in the YouTube community or Monty Python fans who also watched online video? Did your target audience change from when the channel was launched to now?

Goldstone: Because Monty Python has been around for almost 40 years (October 2009 is the 40th anniversary of the first broadcast on BBC TV of Monty Python's Flying Circus), there are possibly now six generations of Monty Python fans around the world, so it wasn't a question of targeting but more about letting YouTube do its miraculous thing and bring its very wide audience into our net.

Jarboe: Did you optimize your videos for YouTube? Are there search terms that you put in the title, description, and tags of your videos?

Goldstone: We gave each clip as much cross reference as possible to make the search that much easier.

Jarboe: What is the most compelling video content on MontyPython's channel? Is it one of the most viewed or most discussed videos? Is it one of your playlists?

Goldstone: Certainly the most compelling, viewed, and discussed is the new introduction video we created for the launch of the channel. I had written the mission statement for the channel, which became the commentary for the introduction video, and we drew on interviews with the Pythons to tell the story. We used the playlist option as a way to create themes, which we continue to populate with new videos.

Jarboe: What is your channel strategy? How much effort was focused on Monty Python's channel on YouTube versus http://pythonline.com? Has this changed since the channel was launched? Will it change going forward?

Goldstone: We have been developing PythOnline, which Eric Idle started in 1996, from its original form into a more interactive, user-generating platform and are about to go for a full launch of the MashCaster, which the folks at New Media Broadcasting Company who manage PythOnline for us have developed as a downloadable software program that enables Terry Gilliam–type animation to be created, shared, broadcast, and uploaded on PythOnline and of course YouTube. User-generated content is therefore a big part of our future direction. (Figure 10.24 shows the PythOnline site home page.)

Jarboe: In addition to creating compelling video content, have you engaged in any outreach effort with the YouTube community or bloggers? Do you give opinion leaders a “heads-up” when a new video is uploaded?

Goldstone: So far we have preferred to provide new content on a regular basis to which YouTube subscribers to the Monty Python Channel are automatically alerted.

Jarboe: What production challenges have you faced and overcome? Are there any tips or tools that you used to get videos uploaded?

Goldstone: Maintaining high-definition quality has been the biggest challenge. Our mission statement criticized the inferior quality of so many of the clips that had been uploaded before the launch of the Monty Python Channel and we wanted to show how good they could and should be.

Jarboe: The YouTube Blog says your “DVDs quickly climbed to No. 2 on Amazon's Movies & TV bestsellers list” when you launched your channel, “with increased sales of 23,000 percent.” Why did you take advantage of YouTube's click-to-buy platform? Did you also use Yahoo! Video ads, InVideo Ads, contests, or other high-profile placements?

Goldstone: The click-to-buy ability was exactly what we were looking for to make the link from video to the right Amazon page much more effective than the URL by the side of the video description. We are only now beginning to address premium advertising, which is only possible when you can show the size, composition, and consistency of your viewers.

Jarboe: How did you measure your video campaign? Did you use YouTube Insight, TubeMogul, or other analytics for online video? Did you use web analytics on http://pythonline.com? What feedback did these tools give you that may have led you to change anything you were doing?

Goldstone: The analysis tools have been very useful for identifying where in the world our viewers are, although, because our DVDs have been available in many countries of the world, we have known for some time where our major audience bases are.

Jarboe: I've been a fan of the Pythons since Monty Python's Flying Circus first aired on the BBC. Did the Pythons create a YouTube channel just to stop their content from being released illegally on the Internet, or is this the beginning of a new chapter in the quest for Global PythoNation?

Goldstone: It certainly started as a way to control what was going on, but the extraordinary response we got to launching our own channel has opened up broader ideas to reach and expand our audience.

That is serious advice from a man who has been producing comedy films in England since the mid-1970s. But, perhaps I should make an appointment with the Argument Clinic (Figure 10.25), because I'd like to have a five-minute argument with Goldstone about one of his statements.

He said, “There are possibly now six generations of Monty Python fans around the world.” But that's highly unlikely for a group that's been around for only 40 years, unless those fans are baboons. According to Wikipedia, a new generation of baboons comes along every five to eight years. So, it's possible that six generations of baboons have been born since 1969.

Figure 10.25 “Argument Clinic”

But let's not bicker and argue over who begat who. If you close your eyes and just listen to the sound that a 23,000 percent increase in DVD sales is making, you can hear the cash register ring.

Generate $2.1 million in Sales: PiperSport Launch

Can you use YouTube to sell a $140,000 product?

I asked Michael Kolowich that question for Search Engine Watch's channel on Feb. 2, 2010 (Figure 10.26).

Figure 10.26 “Light sport aircraft PiperSport social media case study”

I've known Kolowich for more than 30 years. Early in his career, he was a reporter at WGBH-TV in Boston, where he won an Emmy Award for outstanding news reporting. From 1985 to 1988, he was corporate vice president of marketing and business development of Lotus Development Corporation. From 1988 till 1991, he was the founding publisher of PC/Computing.

Kolowich is currently president and executive producer of DigiNovations, which he founded in late 2001. During the 2008 presidential election campaign, he was architect and producer of Mitt TV, the acclaimed video website for the Mitt Romney presidential campaign.

In the past three years, DigiNovations has also produced major projects for Genzime, Harvard Business School, MIT, the Museum of Science, and Piper Aircraft.

On Thursday, January 13, 2010, the Piper Aircraft marketing team faced a dilemma.

The good news was that Piper management had just inked a licensing deal that would allow the company to bring a game-changing personal aircraft to the market, the PiperSport.

The bad news was that launch day for the PiperSport would be just eight days later, on January 21, at a major sport aircraft show in Florida.

The eight-day timeline would be short even for a traditional launch. But PiperSport seemed to be a product tailor-made for social media: a hip new personal transportation product targeted at young pilots at a price point roughly double that of a luxury car. With the timeline tight and the budget even tighter, Piper decided that a digital marketing campaign would be the quickest way to build awareness and excitement about a new airplane.

Commissioning DigiNovations to take the lead, Piper quickly assembled a tightly integrated program on Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter that produced strong awareness, eye-popping sales results, and many turned heads in the aviation marketing field. Piper turned a budget of less than $50,000 into presales of more than a dozen $140,000 aircraft, more than half of which were ordered via $10,000 deposits made through a PayPal web link.

This is the story of that campaign.

With time short and resources scarce, Piper and DigiNovations settled on several objectives:

- Create broad awareness of the new PiperSport within two weeks of launch, as measured by search inquiries, website visits, and social media engagement.

- Steal the thunder from a major competitor, Cessna Aircraft, whose entry in the same class had suffered a major manufacturing delay.

- Create strong interest in the aviation press, fueled by a sense of market interest and momentum, sufficient to earn a major aviation magazine cover.

- Build a communications channel with at least 5,000 “fans” via a social media channel, feeding enthusiasts and evangelists with a steady stream of news and updates.

- Create at least three aircraft sales directly attributable to social media channels, more than amortizing the full cost of the social marketing program with margins on the sold aircraft.

The time horizon of the first phase of the campaign would be January 21 through mid-April, when the first PiperSport would be delivered to the first customer at a major air show in Florida.

The Video

The longest lead-time item would be creation of a marketing video to introduce the PiperSport to the public. Making it trickier was that the initial aircraft were in a secret location and had not yet been certified and insured to fly. The DigiNovations team settled on a highly personalized, informal approach to introducing the PiperSport, featuring key Piper executives taking the viewer on a video “tour” of its features, Piper's chief pilot discussing detailed flying characteristics, and a young woman taking her first lesson in the aircraft.

As Figure 10.27 illustrates, “Inside the PiperSport - the New Light Sport Aircraft from Piper (HD),” has more than 115,000 views. It also has over 100 ratings and 11 comments. And it has been favorited over 160 times.

Figure 10.27 “Inside the PiperSport-the New Light Sport Aircraft from Piper (HD)”

The YouTube Channel

A custom-designed YouTube channel would host not just the main video but also shorter, supplemental “tell me more” pieces built from outtakes as well as video reviews from aviation journalists when they became available. A mechanism was set up to scan for new videos twice a day so that all new independently produced video material could be discovered and “favorited” for inclusion in the PiperSport channel.

PiperSport's channel (Figure 10.28) has more than 84,000 channel views, almost 150,000 total upload views, and over 500 subscribers.

Figure 10.28 PiperSport's channel

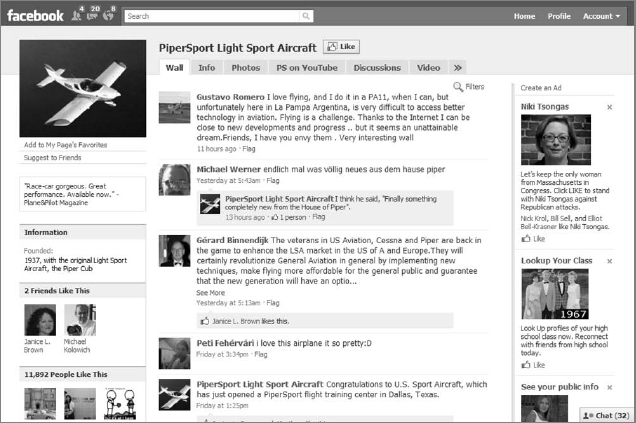

The Facebook Fan Page

The team created a Facebook fan page (facebook.com/PiperSport) and began loading it with useful content so that it would look vibrant and “full” even to the first visitors who arrived. The team took advantage of the fact that there was a small but very enthusiastic cadre of fans of a predecessor to the PiperSport in the United States who could be attracted and cultivated to enthusiastically review and post about the aircraft, even before the official PiperSport would fly in April. This provided plenty of photographs, stories, and personal videos to keep the anticipation high even before the first delivery in April. The Facebook page was launched simultaneously with the announcement and seed-promoted with pay-per-click ads on Facebook targeted at pilots and aviation enthusiasts. The Piper team posted several times a day during the first two weeks, daily for the following month, and even now posts every two to three days (and comments daily).

As Figure 10.29 illustrates, the PiperSport Light Sport Aircraft fan page has almost 11,900 fans, or people who like it. It also has 10 photo albums and has embedded four YouTube videos.

Figure 10.29 PiperSport Light Sport Aircraft

The Twitter Feed

While the Facebook page was targeted at enthusiasts, a Twitter feed (twitter.com/PiperSport) was more narrowly targeted at aviation journalists and opinion leaders. The objective here would be quality, not quantity, to keep opinion leaders well-informed about every event and milestone, new material, and so on. The team measured success here by retweets by opinion leaders to their respective audiences.

As Figure 10.30 illustrates, the PiperSport Twitter feed has more than 400 followers. These include almost 100 percent of a targeted list of aviation journalists, bloggers, and opinion leaders.

Figure 10.30 PiperSport Light Sport Aircraft on Twitter

Here are some of the important results milestones for the social media launch of the PiperSport:

- On January 20, 2010, a Google search for “PiperSport” turned up zero results; it now returns more than 106,000 results. What's more, the company's official channels—website, Facebook page, YouTube videos, Twitter feed, and other materials—occupy 4 out of the top 10 search results.

- The PiperSport program has been cited by Technorati and Search Engine Watch as a groundbreaking program in social media marketing effectiveness. Market enthusiasm inspired Flying Magazine to put PiperSport on its May 2010 cover.

- By late April, at least 15 new PiperSports had been ordered at an average order size of nearly $140,000 each. Eight of these had been bought via $10,000 deposits made through PayPal; Facebook had been credited by at least four buyers publicly as influencing their sale. PiperSports are being sold much faster than they can be made.

Q&A with Michael Kolowich, President and Executive Producer, DigiNovations

I interviewed Kolowich about launching the PiperSport. Here are my questions and his answers.

Jarboe: What's your background? How did you get involved with the PiperSport launch?

Kolowich: I am a marketing advisor to Piper Aircraft, the 73-year-old small airplane manufacturer that brought the PiperSport to market in 2010. Before the launch, the Piper marketing team asked me to review their market-launch plan and to come up with ideas to spice up the introduction of this very cool, sexy airplane that they feel will be a game-changer.

Jarboe: Who is your target audience? Is it opinion leaders in the YouTube community or customers who also watch online video? Did you have different target audiences for YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter?

Kolowich: Pilots—and people who want to be pilots—are heavy users of the Internet and social media. We know this by the traffic on aviation-related websites, blogs, bulletin boards, and online communities. We can also see that pilots post and consume a huge number of YouTube videos. So we believed we could reach potential buyers directly on YouTube and Facebook through a combination of SEM, SEO, and targeted Facebook ads. Twitter, on the other hand, has an extremely active group of influencers—aviation journalists, bloggers, and pundits; our Twitter strategy, therefore, was aimed principally at influencers who could seed and accelerate our direct-to-customer approaches in YouTube and Facebook.

Jarboe: Do you optimize your videos for YouTube? Are there search terms that you put in the title, description, and tags of your videos on YouTube? Are there search terms that you use to optimize videos for Google?

Kolowich: It's important to optimize videos for YouTube—especially in an environment where there are so many pilots watching so many videos. We want to make sure we're seen not just when directly searched for, but also under “related videos” when a viewer is done watching another video. So we comb through our competitors' video titles, descriptions, and tags to find appropriate matches. “Light Sport Aircraft” is the name of the new category of airplane to which the PiperSport belongs, so we certainly optimize around that. Our main brand name, Piper, is also quite popular among pilots as a search term. You'll have to guess our other keywords; I don't want to give away ALL our secrets!

Jarboe: What is the most compelling video content on PiperSport's channel? Is it one of the most viewed or most discussed videos? Is it your playlist?

Kolowich: “Compelling” has a lot of dimensions. All of our videos on the PiperSport YouTube channel are well-watched, but we frankly have roles that each of them plays. By sheer viewing volume, “Inside the PiperSport - the new Light Sport Aircraft from Piper (HD)” would have to be considered the most compelling—especially if you look at the Hot Spots analysis under YouTube Insights, showing much higher-than-normal viewer engagement. But another one that seems to get a lot of pass-around action is a 30-second time-lapse, set to “Flight of the Bumblebee,” that shows a PiperSport being assembled at high speed (Figure 10.31).

Figure 10.31 “Assembling the First PiperSport Light Sport Aircraft... in 30 Seconds!”

Jarboe: What is your channel strategy? How much effort was focused on PiperSport's channel, website, Facebook page, or Twitter feed? Has this changed since the YouTube channel was launched? Will it change going forward?

Kolowich: Facebook and YouTube have equal but complementary roles in our channel strategy. We've found the level of engagement to be much higher with the PiperSport community on Facebook rather than YouTube. But adding new YouTube videos periodically gives us something to post about in Facebook, and we try to post almost daily.

Jarboe: In addition to creating compelling video content, have you engaged in any outreach effort with the YouTube community or bloggers? Do you give opinion leaders a “heads-up” when a new video is uploaded?

Kolowich: We should do more outreach, but with limited resources we rely on Twitter and Facebook posts to get the word out about our videos. People are paying attention—when we post about a new YouTube video on Facebook, it's not unusual to see the YouTube counter go up by almost 1,000 views within hours.

Jarboe: What production challenges have you faced and overcome? Are there any tips or tools that you used to get videos uploaded?

Kolowich: As someone who's been producing video for 38 years, most of the solutions to production challenges are second nature. And in fact, we developed during the last presidential campaign a production process that goes from raw video to online in hours—even minutes, if necessary. We don't upload raw video—it's simply too big, and I'd prefer to do the first-level compression myself; rather, we've developed a set of presets for Apple Compressor, Adobe Media Encoder, and MPEG StreamClip that produce nice, crisp videos that play on YouTube's high-definition settings. Our only frustration is that YouTube defaults to a low-resolution version, so unless the viewer clicks on the settings button, they won't see our nice, pristine high-def version.

Jarboe: Have you taken advantage of any video advertising opportunities? Have you used Promoted Videos or other ad placements?

Kolowich: Promoted Videos (via AdWords) has been essential to seeding our videos initially for a quick start. We place relatively inexpensive keyword buys against both phrases that are too broad to pick up our videos (e.g., “new light sport aircraft”) or that are competitive and wouldn't naturally come up in a search (“Cessna Skycatcher”). This has significantly increased our reach in very short periods of time, at relatively low expense.

Jarboe: How do you measure your video campaign? Do you use YouTube Insight, TubeMogul, or other analytics for online video? Do you use web analytics on www.piper.com? What feedback have these tools given you that may have led you to change anything you were doing?

Kolowich: We watch two things in particular on YouTube Insight: Hot Spots (which helps us determine which scenes work and which ones don't during the course of a video) and Referrals (to watch the progression from Promoted Videos to organic growth). We also track them through to inquiries and conversions on www.piper.com.

Jarboe: How does the launch of the PiperSport compare to other launches by Piper Aircraft? Was anyone at Piper Aircraft surprised that you could use YouTube and video marketing to sell a $140,000 product?

Kolowich: Never before has a Piper aircraft been launched in quite this way. The old approach was to rent space at an air show, hold a news conference, take a lot of reporters and editors up for a flight, and hope for a magazine cover—or at least a favorable review. The combination of Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter fanned the flames of interest in PiperSport to a fever pitch between its announcement in January 2010, and its actual availability 12 weeks later. It was so surprising that the dealer infrastructure, accustomed to a more leisurely ramp-up, was not prepared to handle the volume of inquiries. Fortunately, our website had a way to order the airplane online—and even to place deposits via PayPal. And month by month through the first year, PiperSport continues to exceed all expectations; in 2010, it is expected to outsell all other airplanes in its class.

Now, you can't deposit fans, views, or followers in a bank. But, $2.1 million in sales are worth something. And, if you do the math, generating $2.1 million in sales with a marketing budget of less than $50,000 means that Piper Aircraft got a short-term return on a marketing investment of 42X.

So, you can measure the value of social media and video marketing in cold, hard cash.

However, you'll want to know the epilogue to this story.

On January 12, 2011, Piper Aircraft terminated its business relationship with Czech Republic–based Czech Sport Aircraft to market that company's Light Sport Aircraft, citing differences in business philosophies.

In a press release, Piper CEO Geoffrey Berger said, “After a year working with Czech Sport Aircraft, Piper determined that it is in our company's best long-term interests to discontinue the business relationship which distributed a Light Sport Aircraft manufactured by the Czech company and distributed under Piper's brand by a separate distributor network.”

When I asked Kolowich for a comment, he said, “This story is one of those ’be careful what you wish for' stories.”

He added, “The breakup had nothing to do with the marketing success of the product; in fact, PiperSport became the best-selling light sport aircraft in the world and succeeded beyond its wildest dreams, based in no small measure on the social media and video marketing buzz. Rather, it was a difference in operating philosophy between the two companies that caused the rift.”

He concluded, “Ironically, the fact that the PiperSport had become a social media phenomenon made it that much more difficult for Piper to let go. But the end was announced on—where else?—Facebook. And Piper turned its attention to a much more daunting social media challenge: promoting its $2.5 million PiperJet Altaire, which already has quite a Facebook and YouTube following.”

And now you know … the rest of the story.