In recent years, a simple three-digit number has become critical to your financial life.

This number, known as a credit score, is designed to predict the possibility that you won’t pay your bills. Credit scores are handy for lenders, but they can have enormous repercussions for your wallet, your future, and your peace of mind.

If your credit score is high enough, you’ll qualify for a lender’s best rates and terms. Your mailbox will be stuffed with low-rate offers from credit card issuers, and mortgage lenders will fight for your business. You’ll get great deals on auto financing if you need a car, home loans if you want to buy or improve a house, and small business loans if you decide to start a new venture.

If your score is low or nonexistent, however, you’ll enter a no-man’s land where mainstream credit is all but impossible to come by. If you find someone to lend you money, you’ll pay high rates and fat fees for the privilege. A bad or even mediocre credit score can easily cost you tens of thousands and even hundreds of thousands of dollars in your lifetime.

You don’t even have to have tons of credit problems to pay a price. Sometimes all it takes is a single missed payment to knock more than 100 points off your credit score and put you in a lender’s high-risk category.

That would be scary enough if we were just talking about loans. But landlords and insurance companies also use credit scores to evaluate applicants. A good score can win you cheaper premiums and better apartments; a bad score can make insurance more expensive and a place to live hard to find.

Yet too many people know far too little about credit scores and how they work. Here’s just a sample of the kinds of emails and letters I get every day from people puzzling over their credit:[1]

[1] As with other real-life anecdotes in this book, the writers’ anonymity has been protected and their messages might have been edited for clarity.

“I just closed all of my credit card accounts trying to improve my credit. Now I hear that closing accounts can actually hurt my score. How can I recover from this? Should I try to reopen accounts so that I can have a higher amount of available credit?” Hallie in Shreveport, LA

“How do you get credit if you don’t have it? I keep getting turned down, and the reason is always ‘insufficient credit history.’ How can I get a decent credit score if I don’t have credit?” Manuel in San Diego, CA

“I am a 25-year-old male who made a few bad credit decisions while in college, as many of us do. I need to improve my credit drastically so I do not continue to get my eyes poked out on interest. What can I do to boost my credit score fast?” Stephen in Dallas, TX

“I joined a credit-counseling program because I was in way over my head. But my wife and I plan on buying a house within the next three years, and she has expressed concern that my participation in this debt management program could hurt my credit score. What should I do to help my overall chances with the mortgage process and get the best rate possible?” Paul in Lodi, NJ

“I’m 33 and have never had a single late payment or credit issue in my life. Yet, my credit score isn’t as high as I thought it would be. What does it take to get a perfect score?” Brian in South Bend, IN

What these readers sense, and what credit experts know, is that ignorance about your credit score can cost you. Sometimes people with great scores get offered lousy loan deals but don’t realize they can qualify for better terms. More often, people with bad or mediocre credit get all the loans they want, but they don’t realize the high price they’re paying.

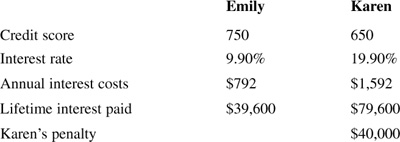

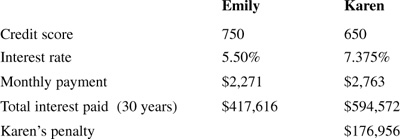

If you need an example of exactly how much a credit score can matter, let’s examine how these numbers affect two friends, Emily and Karen.

Both women got their first credit card in college and carried an $8,000 balance on average over the years. (Carrying a balance isn’t smart financially, but unfortunately, it’s an ingrained habit with many credit card users.)

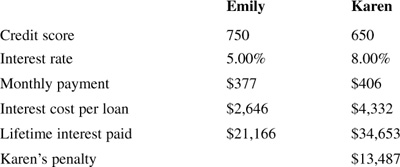

Emily and Karen also bought new cars after graduation, financing their purchases with $20,000 auto loans. Every seven years, they replaced their existing cars with new ones until they bought their last vehicles at age 70.

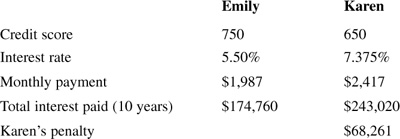

Each bought her first home with $350,000 mortgages at age 30, and then moved up to a larger house with $450,000 mortgages after turning 40.

Neither has ever suffered the embarrassment of being rejected for a loan or turned down for a credit card.

But here the similarities end.

Emily was always careful to pay her bills on time, all the time, and typically paid more than the minimum balance owed. Lenders responded to her responsible use of credit by offering her more credit cards at good rates and terms. They also tended to increase her credit limits regularly. That allowed Emily to spread her credit card balance across several cards. All these factors helped give Emily an excellent credit score. Whenever a lender tried to raise her interest rate, she would politely threaten to transfer her balance to another card. As a result, Emily’s average interest rate on her cards was 9.9 percent.

Karen, by contrast, didn’t always pay on time, frequently paid only the minimum due, and tended to max out the cards that she had. That made lenders reluctant to increase her credit limits or offer her new cards. Although the two women owed the same amount on average, Karen tended to carry larger balances on fewer cards. All these factors hurt Karen’s credit—not enough to prevent her from getting loans, but enough for lenders to charge her more. Karen had much less negotiating power when it came to interest rates. Her average interest rate on her credit cards was 19.9 percent.

Credit Cards

Emily’s careful credit use paid off with her first car loan. She got the best available rate, and she continued to do so every time she bought a new car until her last purchase at age 70. Thanks to her lower credit score, Karen’s rate was three percentage points higher.

Auto Loans

The differences continued when the women bought their houses. During the 10 years that the women owned their first homes, Emily paid $68,000 less in interest.

Mortgage 1 ($350,000)

Karen’s interest penalty only grew when the two women moved up to larger houses. Over the 30-year life of their mortgages, Karen paid nearly $200,000 more in interest.

Mortgage 2 ($400,000)

Karen’s total lifetime penalty for less-than-stellar credit? More than $320,000.

If anything, these examples underestimate the true financial cost of mediocre credit:

• The interest rates in the examples are relatively low in historical terms. Higher prevailing interest rates would increase the penalty that Karen pays.

• Karen probably paid insurance premiums that were 20 percent to 30 percent higher than Emily’s, and she might have had more trouble finding an apartment, all because of her credit.

• The examples don’t count “opportunity cost”—what Karen could have achieved financially if she weren’t paying so much more interest.

Because more of Karen’s paycheck went to lenders, she had less money available for other goals: vacations, a second home, college educations for her kids, and retirement.

In fact, if Karen had been able to invest the extra money she paid in interest instead of sending it to banks and credit card companies, her savings might have grown by a whopping $2 million by the time she was 70.

With so much less disposable income and financial security, you wouldn’t be surprised if Karen also experienced more anxiety about money. Financial problems can take their toll in innumerable ways, from stress-related illnesses to marital problems and divorce.

So, if you’ve ever wondered why some families struggle while others in the same economic bracket seem to do just fine, the answers typically lie with their financial habits—including how they handle credit.

The question remains: How did one little number come to have such an outsized effect on our lives?

Credit scoring has been in widespread use by lenders for several decades. By the end of the 1970s, most major lenders used some kind of credit-scoring formulas to decide whether to accept or reject applications.

Many were introduced to credit scoring by two pioneers in the field: engineer Bill Fair and mathematician Earl Isaac, who founded the firm Fair Isaac in 1956. Over the years, the pair convinced lenders that mathematical formulas could do a better job of predicting whether an applicant would default than even the most experienced loan officers.

A formula wasn’t as subject to human whims and biases. It wouldn’t turn down a potentially good credit risk because the applicant was the “wrong” race, religion, or gender, and it wouldn’t accept a bad risk because the applicant was a friend.

Credit scoring, aided by ever more powerful computers, was also fast. Lending decisions could be made in a matter of minutes, rather than days or weeks.

Early on, each company had its own credit-scoring formula, tailored to the amount of risk it wanted to take, its history with various types of borrowers, and the kind of people it attracted as customers. The factors that fed into the formula varied, but many took into account the applicant’s income, occupation, length of time with an employer, length of time at an address, and some of the information available on his or her credit report, such as the longest time that a payment was ever overdue.

These calculations took place behind the scenes, invisible to the consumer and understood by a relatively small number of experts and loan executives.

The cost to develop and implement these custom formulas was—and still is—considerable. It was not unusual to spend $100,000 or more and take 12 months just to set one up. In addition, not every creditor had a big enough database to work with, especially if the company wanted to branch out into a new line of lending. A credit card lender that wanted to start offering car loans, for example, might find that its database couldn’t adequately predict risk in vehicle lending.

That led to credit scores that are based on the biggest lending databases of all—those that are held at the major credit bureaus, which include Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion. Fair Isaac developed the first credit bureau-based scoring system in the mid-1980s, and the idea quickly caught on.

Instead of basing their calculations on any single lender’s experience, this type of scoring factored in the behavior of literally millions of borrowers. The model looked for patterns of behavior that indicated a borrower might default, as well as patterns that indicated a borrower was likely to pay as agreed. The score evaluated the consumer’s history of paying bills, the number and type of credit accounts, how much available credit the customer was using, and other factors.

This credit-scoring model was useful for more than just accepting or rejecting applicants. Some lenders decided to accept higher-risk clients but to charge them more to compensate for the greater chance that they might default. Lenders also used scores to screen vast numbers of borrowers to find potential future customers. Instead of waiting for people to apply, credit card companies and other lenders could send out reams of preapproved offers to likely prospects.

Credit scoring is one of the reasons why consumer credit absolutely exploded in the 1990s. Lenders felt more confident about making loans to wider groups of people because they had a more precise tool for measuring risk. Credit scoring also allowed them to make decisions faster, enabling them to make more loans. The result was an unprecedented rise in the amount of available consumer credit. Here are just a few examples of how available credit expanded during that time:

• The total volume of consumer loans—credit cards, auto loans, and other nonmortgage debt—more than doubled between 1990 and 2000, to $1.7 trillion.

• The amount of credit card debt outstanding rose nearly threefold between 1990 and 2002, from $173 billion to $661 billion.

• Home equity lending soared from $261 billion in 1993 to more than $1 trillion ten years later.

Credit scoring got a huge boost in 1995. That’s when the country’s two biggest mortgage-finance agencies, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, recommended lenders use FICO credit scores. Because Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac purchase more than two-thirds of the mortgages made, their recommendations carry enormous weight in the home loan industry.

The recommendations are also what finally began to bring credit scoring to the public’s attention.

If you’ve ever applied for a mortgage, you know it’s a much more involved process than getting a credit card. When you apply for a credit card, you typically fill out a relatively brief form, submit it, and get your answer back quickly—sometimes within minutes, if you’re applying online or at a retail store. The process is highly automated, and there typically isn’t much personal contact.

Contrast that with a mortgage. Not only do you have to provide a lot more information about your finances, but getting a home loan also requires that you have ongoing personal contact with a loan officer or mortgage broker. You might be asked to clarify something in your application, be told to supply more information, or be given updates about how your request for funds is being received.

It was in the course of those conversations that an increasing number of consumers starting hearing about FICOs and credit scores. For the first time, people learned that the reason they did or didn’t get the loan they wanted was because of a three-digit number. It became obvious that lenders were putting a lot of stock in these mysterious scores.

But when consumers tried asking for more details, they often hit a brick wall. Fair Isaac, the leader in the credit-scoring world, wanted to keep the information secret. The company said it worried that consumers wouldn’t understand the nuances of credit scoring, or they would try to “game the system” if they knew more. Fair Isaac feared that its formulas would lose their predictive ability if consumers started changing their behavior to boost their scores.

Now, some sympathetic mortgage officials didn’t buy into Fair Isaac’s company line. They thought consumers deserved to know their score, and these officials also often tried to explain how the numbers were created.

Unfortunately, because Fair Isaac wouldn’t disclose the formula details, a lot of these explanations were dead wrong. Even more unfortunately, some loan officers perpetuate these myths about credit scoring, despite the fact that we have much more information about what goes into them. (You’ll read more on these myths in Chapter 5, “Credit-Scoring Myths.”)

Resentment about the secret nature of credit scores came to a head in early 2000. That’s when one of the then-new breed of Internet lenders, E-Loan, defied Fair Isaac by letting consumers view their FICO credit scores. For about a month, people could actually take a peek at their scores online and learn some rudimentary information about what the numbers meant. Some 25,000 consumers took advantage of the free service before E-Loan’s source for credit-scoring information was cut off.

But the proverbial cat was out of the bag. A few months later, with consumer advocates demanding disclosure and lawmakers drafting legislation requiring it, Fair Isaac caved. It posted the 22 factors affecting a credit score on its Web site, grouped into the 5 categories you’ll read about in the next chapter. Shortly after that, the company partnered with credit bureau Equifax to provide consumers with their credit scores and reports for a $12.95 fee.

In late 2003, Congress finally got around to passing a law that gave people a right to see their scores. By the time this update to the Fair Credit Reporting Act was signed into law, however, access to credit scores was almost old hat.

Controversies over credit scoring continue to rage. Here are just of few of them.

No matter how good the mathematics of credit scoring, it’s based on information in your credit report—which may be, and frequently is, wrong. Sometimes the errors are small or irrelevant, such as when your credit file lists a past employer as a current employer. Other times the problems are significant, such as when your file contains accounts that don’t belong to you. Many people discover this misinformation only after they’ve been turned down for credit.

The credit bureaus handle billions of pieces of data every day, so to some extent, errors, outdated, and missing information are inevitable—but the credit-reporting system often makes it difficult to get rid of errors after you spot them.

The problem is only getting worse. The rise in automated lending decisions means a human might never see your application or notice that something’s awry. The explosion in identity theft, with its ten million victims a year, means more bad, fraudulent information is included in innocent people’s credit files every day.

Patricia of Seattle, Washington, tells of the ongoing horror of becoming a victim:

“I’ve always been careful about protecting my identity. Unfortunately, when I was trying to purchase a home, the real estate broker, to whom I’d given my application with birth date and Social Security number, had her laptop stolen. My worst fears came true when, four months later, I suddenly had creditors calling me like crazy asking why I wasn’t paying on accounts that were just recently opened in my name. On top of this, I learned the criminals had also stolen my mail with preapproved credit cards. This has created a nightmare of time, work, and frustration trying to clean up my credit history. It’s been over two years now, and I’m still working with the major credit-reporting agencies as we speak.”

You’re being judged by the formula, so shouldn’t it be easy to understand and predictable? Not even credit-scoring experts can always forecast in advance how certain behaviors will affect a score. Because the formula takes into account so many variables, the best answer they can muster is, “It depends.”

The variety of different scoring formulas and different approaches among lenders can confuse matters even further.

Lenders can get scores calculated from different versions of the FICO formula. They also can have in-house formulas that incorporate a FICO score along with other information that might punish or reward certain behaviors more heavily than the FICO formula does on its own. Some call the result a FICO score, even though that’s not technically correct.

Not surprisingly, this causes confusion for consumers and mortgage professionals alike.

A. J. Cleland, an Indianapolis mortgage broker, discovered how different scores could be when trying to help a client who had been turned down for a loan by a bank. The bank reported the client’s FICO score was 602, whereas the FICO score Cleland pulled for the client—on the same day and from the same credit bureau—was 31 points lower:

“I called my credit provider and was informed that there are different types of reports and different scores,” Cleland said. “I thought your score was your score, period.”

I mentioned earlier that your landlord or employer might check your credit and your credit score when evaluating your application; however, the most controversial noncredit use of scoring is in insurance.

Insurers have discovered that there’s an enormously strong link between the quality of your credit and the likelihood you’ll file a claim. They can’t really explain it, but every large study of the issue has confirmed that this link exists. The worse your credit, the more likely you will cost an insurer money. The better your credit, the less likely you are to have an accident or otherwise suffer an insured loss.

As a result, more than 90 percent of homeowners and auto insurers use credit scoring to decide who to cover and what premiums to charge them.

That outrages many consumers and consumer advocates who don’t see a logical connection between credit and insurance. Julie, a city worker in Poulsbo, Washington, saw her insurances soar after a divorce and subsequent bankruptcy trashed her credit:[2]

[2] Like many divorced people, Julie discovered that her ex still had the power to trash her credit long after the marriage was over. His unpaid bills, run up on once-joint accounts, showed up on her credit report and ultimately led her to file bankruptcy.

“I have had the same insurer for 30 years, never been late, never missed a payment, never had an accident, and never filed a claim—yet now I pay the price of higher rates. I absolutely do not understand how this is fair.”

This leads to another controversy, spelled out in the next section.

Developers of credit scoring point out their formulas are designed not to discriminate. Credit scores don’t factor in your income, race, religion, ethnic background, or anything else that’s not on your credit report.

But it’s not clear whether the result of those formulas actually is nondiscriminatory. Some consumer advocates worry that some disadvantaged groups might suffer disproportionately as a result of credit scoring.

Among their theories: People who have low incomes or who live in some minority neighborhoods might have less access to mainstream lenders and thus have worse credit scores. The lenders these disadvantaged populations do use—finance companies, subprime lenders, and community groups—might not report to credit bureaus, making it harder to build a credit history. If these lenders do report to the bureaus, their accounts might count for less in the credit-scoring formula than those of mainstream lenders. Seasonal work is also more prevalent in some neighborhoods, which can lead to a higher rate of late payments in the off-seasons.

Even if credit scoring doesn’t discriminate against groups, it might discriminate against you.

No credit-scoring system is perfect. Lenders know that their formulas will reject a certain number of people who actually would have paid their bills. Another group will be accepted as good risks, but then default.

If these groups get too large, the lender has trouble. When too many bad applicants are accepted, the lender’s profits plunge. When too many good applicants are rejected, the lender’s competitors can scoop them up and make more money.

But lenders accept a certain number of misclassified applicants as a cost of doing business. That’s little comfort to you, if you’re one of the responsible ones who loses out on the mortgage you need to buy a home, or if you end up paying more for it.

Given all the problems with credit scoring, it’s understandable that some people think the system is fatally flawed. Some of my readers tell me they’re so angry about scoring and the behavior of lenders in general that they’ve cut up their credit cards and are determined to live a credit-free life.

The rest of us, though, live in a world where credit is all but a necessity. Few of us can pay cash for a home, and many need loans to buy cars. Credit can help launch a new business or pay for an education. And most Americans like the convenience of using credit cards. Although it’s true that improper use of credit can be disastrous, credit properly used can enhance your life.

If we want to have credit, we need to know how credit scoring works. Knowledge is power, and the tools I give you in this book will help you take control of your credit and your financial life.