The first thing you need to know about your credit score is that you don’t have a credit score: You have many, and they change all the time.

Credit scores are designed to be a snapshot of your credit picture—typically, the picture that’s contained in your credit report. New information is constantly being added to your report, and old information is being deleted. Those changes affect your score.

That can be good news or bad news. The good news is that if you have a bad score now, you’re not stuck with it forever. You can do a lot to improve your situation and make yourself more creditworthy in lenders’ eyes.

The bad news is that you can’t rest on your laurels. When you have a good score, you need to constantly monitor your credit to make sure it stays that way.

You also should know that there’s more than one credit-scoring system out there. In fact, currently more than 100 credit-scoring models are being marketed to lenders. The best-known credit-scoring model, the FICO, is designed to predict whether a borrower will default. But credit-scoring systems have been created to do all of the following:

• Detect fraud in credit or insurance applications

• Calculate the amount of profit a credit card issuer is likely to make on a particular account

• Predict the risk of a specific kind of default, such as bankruptcy

• Forecast the probability that a policyholder will cost an insurer money

• Anticipate the risk that a consumer will default on a certain type of account, such as an auto loan, a mortgage, a cellular phone account, or a utility bill

• Estimate how much a borrower is likely to pay, if anything, on a delinquent account

• Anticipate which customers might close a credit card account or pay the balance down to zero

• Predict the likelihood that someone will respond to a direct-mail credit card solicitation

The vast majority of these scoring systems are developed by the same company that created the FICO: Fair Isaac. In addition, the credit bureaus and some outside companies have created their own formulas.

All that being said, you’re much more likely to be affected by a FICO score than any other type of credit score. FICO is the industry leader. It’s used in literally billions of lending decisions each year, including 75 percent of mortgage-lending assessments.

That’s why the information in this chapter and elsewhere is based on how the FICO formula calculates your score. Other formula designs might differ somewhat in their details, but the behaviors that help and hurt your score are pretty consistent across the various systems.

Here are some other facts about credit scoring that you should keep in mind:

• You need to have and use credit to have a credit score—The classic FICO formulas need at least one account on your credit report that has been open for six months and one account that’s been updated in the past six months. (It can be the same account.) If your credit history is too thin, or you’ve stopped using credit for a period of time, there might not be enough current data in your file to create a regular credit score. (That doesn’t mean you can’t be “scored.” In mid-2004, Fair Isaac introduced the FICO Expansion Score for lenders who want to evaluate people with thin or nonexistent credit histories. This new score uses nontraditional information sources such as companies that monitor bounced checks.)

• A credit score usually isn’t the only thing lenders consider—In mortgage-lending decisions, in particular, lenders may weigh a lot of other information, including your employment history and stability, the value of the property you’re buying or refinancing, your income, and your total monthly debt payments as a percentage of that income, among other factors.

So, although credit scores can be a powerful force in lending decisions, they might not be the sole determinant of whether you get credit.

• Credit-scoring systems were designed for lenders, not consumers—In other words, scores weren’t created to be easy to understand. The actual formulas, and many of the details of how they work, are closely guarded trade secrets.

The credit-scoring companies don’t want the process to be transparent or predictable, as discussed in the preceding chapter. They fear that letting out too many details would allow competitors to copy their formulas. They also worry that their formulas would lose their ability to predict risk if consumers knew exactly how to beat them.

We know more about the formulas than ever before, and certainly enough for you to improve your score. But given the number of variables involved and the mystery still surrounding credit scoring, you may not be able to forecast exactly how every action will affect a score, or how quickly.

One of the first questions many people have about credit scoring is what score lenders consider “good.” There is, however, no single answer to that question.

Generally, of course, the higher the score, the better. Each lender makes its own decision about where to draw the line, based on how much risk it wants to take and how much profit it thinks it can make with a given blend of customers. Many lenders don’t have a single cutoff but may have many, with each segment qualifying for different rates and terms. Finally, as noted earlier, a credit score is usually only one factor in the lending decision. Although scores typically have a big influence, a lender might decide that other factors are more important.

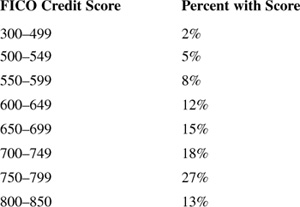

You can see from this national distribution chart of FICO credit scores that most of the U.S. population has a FICO score of 700 or higher. Many lenders use 700 or 720 as the cutoff for giving borrowers their best rates and terms. Many also use 620 as a cutoff point. Companies that deal with borrowers below that level are often called “subprime” lenders because their riskier borrowers are considered less than “prime.”

Because your score is constructed from the information in your credit report, it’s worth looking at what you’ll find there.

In addition to identifying information about you—your name, address, and Social Security number—your report lists the following:

• Your credit accounts—Sometimes called “trade lines,” these include loans, credit cards, and other credit accounts you’ve opened. Your report lists the type of account, how long ago you opened it, your balances, and details of your payment history.

• Requests for your credit—These are known as “inquiries,” and there are basically two kinds. When you apply for credit, you authorize the lender to view your credit history. This is known as a “hard inquiry” and can affect your credit score. You might also see inquiries that you didn’t initiate. These “soft inquiries” are typically made when a lender orders your credit report to make you a preapproved credit offer. Such marketing efforts don’t affect your score.

• Public records and collections—These can include collection accounts, bankruptcies, tax liens, foreclosures, wage garnishments, lawsuits, and judgments.

Public records are culled from state and county courthouses. Lenders or collection agencies report most of the other information in your report.

This data is collected, stored, and updated by credit bureaus, which are private, for-profit companies. The three major credit bureaus are Equifax, Experian (formerly known as TRW), and TransUnion, and their business is selling information about you to lenders.

Because they’re competitors, the bureaus typically don’t share information, and not all lenders report information to all three bureaus. In fact, if you get copies of your credit reports from the bureaus on the same day, you’re likely to notice at least a few differences among them. An account that’s listed on one credit bureau’s report might not show up on the others, for example, or the balances showing on your various accounts might differ from bureau to bureau.

Because your score is based on the information that’s in your report at a given credit bureau, the number differs depending on which bureau’s credit report is used.

Also, each time you or a lender “pulls” your score (in other words, orders a score to be calculated), it’s likely to be at least somewhat different, because the information on which it’s based probably has changed. Fair Isaac says most people’s scores don’t change all that much in a short period, but about 25 percent of consumers can expect to see their scores at a single bureau vary by more than 20 points over a three-month stretch.

There are time limits to what can appear on your credit report. Although positive information can appear indefinitely, negative marks—late payments, collection actions, and foreclosures—by federal law generally must be removed after seven years. Bankruptcies can be reported for ten years. Inquiries should be deleted in two years.

When most of us think of scores, we think of the relatively straightforward systems used in sports or in school tests. You get points (and possibly demerits) for certain actions, behaviors, or answers, and those are totaled to determine your score.

Credit scoring isn’t nearly so easy. Credit-scoring models use “multivariate” formulas. That basically means that the value of any given bit of information in your report might depend on other bits of information.

To understand how this works, let’s use a noncredit example. Suppose that your sister calls you to report that her husband is more than an hour late in coming home from work, and she asks whether you think he’s having an affair. To answer the question, you would need to review what you know about this man, including his attitude about his family, his general moral standards, and whether he’s had dalliances in the past. Using all these variables, you could try to predict whether your brother-in-law is likely to be stepping out—or might just have stopped off to buy his wife an anniversary present.

Let’s suppose that your brother-in-law is a stand-up guy. But you’ve personally observed your neighbor in a clinch with a woman who was not his wife. If your neighbor was an hour late in coming home and his wife asked you your opinion of his likely faithfulness, you might reach quite a different conclusion. So the same behavior—coming home late—could evoke two very different predictions based on the information at your disposal.

The number of factors that the FICO formulas evaluate is infinitely greater, so you can see how difficult it can be sometimes to predict the outcomes of certain behaviors.

There’s one thing that’s always true, though: The FICO model is set up to place more value on current behavior than on past behavior. That means that the effect of your old credit troubles lessens over time if you start handling credit more responsibly.

However, the scores are also designed to react strongly to any signs that a once-good risk might be turning bad. That’s why someone with a good score might suffer more heavily from a late payment.

It’s generally a lot easier to lose points on your score than it is to gain them back, which is why it’s so important to know how to improve and protect your score.

Now that you understand in general how credit scores are calculated, we can move on to some specifics. The following are the five main factors that affect your FICO score according to their relative level of importance, along with a percentage figure that reflects how heavily that factor is weighed in calculating FICO scores for the general population. Each factor might weigh more or less heavily in your individual score, depending on your credit situation.

This makes up about 35 percent of the typical score. It makes sense: Your record of paying bills says a lot about how responsible you are with credit. Lenders want to know whether you pay on time and how long it’s been since you’ve been late, if ever.

To put this in perspective: More than half of Americans don’t have a single late payment on their credit reports, according to Fair Isaac, and only 3 in 10 have ever been 60 days or more overdue in the past 7 years.

When it comes to negative marks like late payments, the score focuses on three factors:

• Recency—This is how recently the borrower got into trouble. The more time that’s passed since the credit problem, the less it affects a score.

• Frequency—As you might expect, someone who has had just one or two late payments typically looks better to lenders than someone who has had a dozen.

• Severity—There’s a definite “hierarchy of badness” when it comes to your credit score. A payment that’s 30 days late isn’t considered as serious as one that’s 60 or 120 days late. Collections, tax liens, and bankruptcy are among the biggest black marks.

If you’ve never been late, your clean history will help your score. But that doesn’t mean you’ll get a “perfect” score. A good credit history involves a lot more.

This equates to 30 percent of your score. The score looks at the total amount owed on all accounts, as well as how much you owe on different types of accounts (credit card, auto loan, mortgages, and so on).

To put this in perspective: Most Americans use less than 30 percent of their available credit limits, according to Fair Isaac. Only 1 in 7 uses 80 percent or more of available limits.

As you might expect, using a much higher percentage of your limits will worry lenders and potentially hurt your score. People who max out their credit limits, or even come close, tend to have a much higher rate of default than people who keep their credit use under control.

When it comes to revolving debt—credit cards and lines of credit—the credit score formula looks at the difference between your credit limits on the accounts and your balance, or the amount of credit you’re actually using. The bigger the gap between your balance and your limit, the better.

Here’s a point that needs clarification: Lenders report your balances to the credit bureaus on a given day (usually each month, but sometimes only every other month or quarterly). It doesn’t matter whether you pay the balance off in full the next day—the balance you owed on the reporting day is what shows up on your credit report. That’s why people who pay off their credit cards in full every month still might have balances showing on their reports.

So you need to be careful with how much you charge, even if you never carry a balance from month to month. Your total balance during the month should never approach your credit limit if you want a good score.

The score also looks at how much you owe on installment loans (mortgages, auto loans) compared to what you originally borrowed. Paying down the balances over time tends to help your score.

This is 15 percent of your total score. As such, it’s generally much less important than the previous two factors, but it still matters. You can have a good score with a short history, but typically the longer you’ve had credit, the better.

To put this in perspective: The average American’s oldest account has been established for about 14 years, according to Fair Isaac. One in four has an account that’s been established for 20 years or more.

The score considers both of the following:

• The age of your oldest account

• The average age of all your accounts

This is 10 percent of your overall score. Opening new accounts can ding your credit score, particularly if you apply for lots of credit in a short time and you don’t have a long credit history.

To put this in perspective: The average American has not opened an account in 20 months.

The score factors in the following:

• How many accounts you’ve applied for recently

• How many new accounts you’ve opened

• How much time has passed since you applied for credit

• How much time has passed since you opened an account

You might have heard that “shopping around” for credit can hurt your score. We deal with this issue more thoroughly in Chapter 4, “Improving Your Score—The Right Way,” but the FICO formula takes into account that people tend to shop around for important loans such as mortgages and auto financing. As long as you do your shopping in a fairly concentrated period of time, it shouldn’t affect the score used for your application.

Also, pulling your own credit report and score doesn’t affect your score. So long as you do it yourself, ordering from a credit bureau or a reputable intermediary, the inquiry won’t count against you. If you have a lender pull your score “just to see it,” though, you could end up hurting your score.

This is 10 percent of your score. The FICO scoring formula wants to see a “healthy mix” of credit, but Fair Isaac is customarily vague about what that means.

The company does say that you don’t need to have a loan of each possible type—credit card, mortgage, auto loan, and so on—to have a good score. Furthermore, you’re cautioned against applying for credit you don’t need in an effort to boost your score, because that can backfire.

To get the highest possible scores, however, you need to have both revolving debts like credit cards and installment debts like an auto loan, mortgage, or personal loan. These latter loans don’t have to still be open to influence your score. But they do still need to show up on your credit report.

Bankcards—major credit cards such as Visa, MasterCard, American Express, Discover, and Diner’s Club—are typically better for your credit score than department store or other “finance company” cards. (Department stores’ cards are typically issued by finance companies, which specialize in consumer lending and which, unlike banks, don’t receive deposits.)

Installment loans can reflect well on you, too. That’s because lenders generally require more documentation and take a closer look at your credit before granting the loan.

To put this in perspective: The average American has 13 credit accounts showing on their credit report, including 9 credit cards and 4 installment loans, according to Fair Isaac.

How these five factors are weighed when it comes to you—as opposed to the general population—depends on a little-known sorting system known at Fair Isaac as “scorecards.”

Scorecards allow the FICO formula to segment borrowers into one of ten different groups, based on information in their credit reports.

If the credit history shows only positive information, the model takes into account the following:

• The number of accounts

• The age of the accounts

• The age of the youngest account

If the history shows a serious delinquency, the model looks for these:

• The presence of any public record, such as a bankruptcy or tax lien

• The worst delinquency, if there’s more than one on the file

After the model has this information, it decides which of the ten scorecards to assign. Although Fair Isaac keeps the details pretty secret, it’s known that there is at least one scorecard for people with a bankruptcy in their backgrounds, and another for people who don’t have much information in their reports.

Grouping people this way is supposed to enhance the formula’s predictive power. The theory is that the same behavior in different borrowers can mean different things. Someone with a troubled credit history who suddenly opens a slew of accounts, for example, might be seen as a much greater risk that someone with a long, clean history. Scorecards allow the FICO formula to give different weight to the same information.

Sometimes, however, the actual results of the scorecards can be a little bizarre.

Naomi of Richmond, Virginia, spent years rebuilding her credit and couldn’t wait for the seven-year mark to pass on three negative items on her credit report: two collection actions and a judgment. These items, she was sure, were the only things holding her credit score down.

When the black marks disappeared from her report, however, Naomi’s score actually dropped more than 20 points. Naomi got caught in what can be a jarring transition from one scorecard to the next.

The negative items on her credit report got her assigned to a certain scorecard, but her efforts to rebuild her credit—making payments on time and using credit responsibility—helped her rise to the top of that scorecard group.

When her negative marks disappeared, though, she was transferred to another group with tougher standards. In that group, she was closer to the bottom, and her credit score drop reflected her fall.

Naomi’s only solace is that the responsible credit behavior she’s learned should help boost her score and recover lost ground over time.

You need to know about a few more complications.

Although all three bureaus use the FICO scoring model, the actual formula differs slightly from bureau to bureau. That’s because the way the bureaus collect and report data isn’t exactly the same. It’s unlikely that these differences would have much impact on your score, but you should know that they exist. You’re much more likely, though, to have different scores from bureau to bureau because the underlying information is different.

As discussed earlier, lenders can have their own in-house scoring formulas in addition to, or instead of, using FICO scores. Lenders also can use different “editions” of the FICO formula. Just as not everyone updates to the latest computer operating systems when they’re released, not every lender uses the latest versions of credit-scoring formulas.

Older versions of the FICO formula, for example, counted participation in a credit-counseling program as a negative factor; newer versions view it as a neutral factor. So, if you’re currently in a debt management program, you might be viewed more negatively by some lenders than by others.

Just consider what happened to Marvin, a home buyer who learned too late that his scores weren’t what he thought they were.

Marvin purchased FICO scores from each of the three credit bureaus. Because lenders usually use the middle of your three scores to determine your interest rates, Marvin was happy to discover his middle score was 638—not great, but high enough to avoid the 620 mark many lenders use to classify a borrower as subprime, or high risk.

When Marvin applied for a loan, however, the lender told him his middle score was 593. It’s not clear whether the lender was using an older FICO formula or was simply using its own modified concoction and calling it a FICO, but Marvin paid the price:

“No one tells you this when you pay your money to get your score,” Marvin said. “We actually put our house on the market based on the information we received from the agencies, having to scramble later for a mortgage company to accept our lower score. We went from being able to receive competitive interest rates to being considered very high risk and receiving very high rates.”

You can help protect yourself somewhat from these discrepancies by being preapproved for a home loan before you start house shopping. But this is just another reason why it’s important to improve and protect your score. The higher your score is, the less you have to worry about a few points making a difference.

If you’ve surfed the Internet lately, you might find it hard to believe that credit scores were secret only a few short years ago. Sometimes it seems like every other Web site is either hawking credit scores or running an ad for a Web site that does.

As you’ve read, though, not all credit scores are created equal.

The credit bureaus, for example, sometimes market scores to consumers that aren’t based on the FICO formula—the one typically used by lenders. The bureaus say these scores are a good indicator of a consumer’s creditworthiness, but their results can differ—sometimes markedly—from the FICO numbers that lenders use.

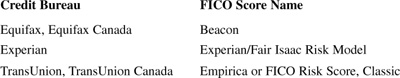

Your first step: Make sure you’re getting a real FICO score. If it doesn’t say FICO or use one of the credit bureau’s trademarked names for FICO scores, it’s not the same formula lenders use.

The FICO score has different names at the three major credit bureaus.

Be careful not to be misled by pitches that promise “free” access to your credit score. Typically, those offers require signing up for credit monitoring or other ongoing services that are most assuredly not free. Although you might decide that these services are helpful, make sure to read the fine print so that you understand what you’re getting and how you can cancel if necessary. Another caution: Some fly-by-night operators might pitch credit scores as a way to get you to reveal your private financial information, such as your Social Security number or credit card numbers. As always on the Web, it’s best to do business with companies you know and to make sure you have a secure connection before transmitting sensitive information. Congress in 2003 gave U.S. residents the right to get free copies of their credit reports annually from each of the three bureaus. But that doesn’t include the right to free scores; the bureaus can and will continue to charge for those.

One place to look for your score is MyFICO.com, a joint venture between Fair Isaac and Equifax. The site offers your credit reports and FICO scores from each of the three bureaus for about $47.85. (One score and one report is $15.95.)

In Canada, you can get your FICO score from Equifax Canada.

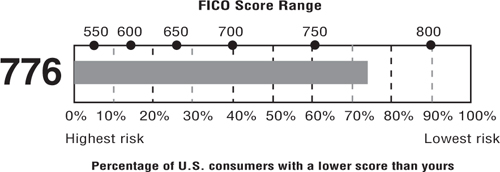

Along with your score, MyFico.com provides a “fever” chart that shows where you stand in relation to other borrowers, along with a summary of how lenders are likely to view you as a credit risk.

In Figure 2.1, the borrower has an Experian FICO score of 776, which puts her ahead of about 75 percent of other Americans.

MyFico.com goes on to tell you more what this means, saying in part:

Lenders consider many factors in addition to your credit score when making credit decisions. Looking solely at your FICO score, however, most lenders would consider this score as excellent.

This means: It is extremely unlikely your application for credit cards or for a mortgage or auto loan would be turned down, based on your score alone.

You should be able to obtain relatively high credit limits on your credit card.

Most lenders will consider offering you their most attractive and most competitive rates.

Many lenders will also offer you special incentives and rewards targeted to their “best” customers.

Source: MyFico.com

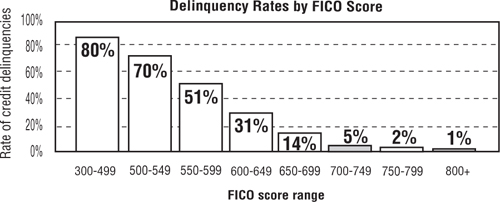

Because the primary purpose of a FICO score is to predict default risk, you might be interested to know how you stack up in that regard. As you can see from the following chart, compiled by MyFico.com for a borrower with a FICO score of 700, the risk of fault rises dramatically as scores drop:

When you get your FICO, you should get a summary of the major factors influencing your score. Be sure to read these carefully, along with any additional explanatory information. These factors are provided to give you some clues about how to improve your score, but if you misinterpret the results, you could end up making things worse.

For example, many people with good credit often find that one of the reasons their score isn’t higher is that they have “too many credit cards.” They think they can solve the problem by closing cards, but the FICO formula doesn’t work that way. The closed cards remain on your credit report and continue to influence your score. In fact, the act of closing accounts can actually hurt your score, as I explain later, and can never help it.

The positive factors you’ll see should be listed in order of importance, and might be something like the following:

• You have no late payments reported on your credit accounts.

• You demonstrate a relatively long credit history.

• You have a low proportion of balances to credit limits on your revolving/charge accounts.

Negative factors, too, should be listed in order of importance. If you have a bankruptcy, collections action, or other serious delinquency, that would be mentioned first. Other negatives that can show up for even the best borrowers include the following:

• You have recently been seeking credit or other services, as reflected by the number of inquiries posted on your credit file in the past 12 months.

• You have a relatively high number of consumer finance company accounts being reported.

• The proportion of balances to credit limits (high credit) on your revolving/charge accounts is too high.

• The length of time your accounts have been established is relatively short.

Now, nobody likes criticism, and some people get absolutely furious when they read through the reasons they’re given for why their score isn’t higher. Interestingly, many of these folks tend to have excellent credit, but—like Brian in the previous chapter—they’re angry that their score isn’t “perfect.”

Understand that nobody is “perfect,” and even if you could achieve a perfect FICO score, the changing circumstances of your life and your credit use would mean you wouldn’t keep that score for long.

Also understand that the negative reasons listed are less and less important the higher your score. The bureaus need to give you some reason for why your scores aren’t higher, but when your score is already in the mid-700s and above, there’s no guarantee that even if you could fix the “problem” that your scores would rise that much.

Still, you can always learn something from reading the reasons given. A notation that your balances are too high should spur you to pay down your debt, for your own financial health as well as for the sake of your score. Getting dinged for having too many cards should keep you from applying for yet another department store card just to get a 10 percent discount. You don’t need one more piece of plastic to keep track of, anyway.

If your score is low, however, you should take the negative factors to heart. They can provide a blueprint for fixing your credit and boosting your score. In Chapter 4, you’ll find general information about improving your score, and in later chapters, I discuss more specific strategies for people who have troubled credit.

Early in 2008, Fair Isaac announced it would be rolling out a new iteration of the FICO called FICO 08.

The new score, Fair Isaac promised, would do a better job of predicting defaults, particularly among customers with poor, thin, or young credit histories. Compared to the classic FICO, FICO 08

• Is less punishing to those who have had a serious credit setback, such as a charge-off or a repossession, as long as their other active credit accounts are all in good standing.

• Entirely ignores small collections where the original debt was less than $100. (This is a huge victory for consumers, many of whose credit reports have been tarnished by small-ticket disputes and minor medical bills their insurance companies failed to pay.)

• Is even more sensitive to the balances reported on consumers’ credit cards.

• Responds more positively if borrowers have both revolving and installment accounts.

• Responds more negatively if consumers have few open, active accounts.

• Protects against so-called authorized user abuse.

As I discuss in Chapter 4, adding a spouse or child to your credit card as an authorized user has long been a good way to boost that person’s credit score, because your good history with the account could be imported to their credit file. But in 2007, credit repair firms began abusing this feature by “renting” authorized user slots from good credit risks and selling them to complete strangers who wanted to boost their scores. Some of these strangers bought slots on dozens of different people’s cards, boosting their scores by tens or even hundreds of points.

Fair Isaac originally said FICO 08 would combat possible fraud by ignoring all authorized user information, drawing protests from consumer advocates who pointed out that the change would punish the innocent as well as the guilty. Furthermore, experts theorized that ignoring information regarding spouses on authorized credit lines could be a violation of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act.

So Fair Isaac rejiggered the FICO 08 formula to include authorized user accounts “while materially reducing potential impacts to the score,” according to the company’s FICO 08 marketing brochure. Exactly how it does that is as secret as the rest of the formula, but speculation is that the new score will count a limited number of authorized user accounts and ignore the rest.

Another change Fair Isaac made after unveiling the new score was in how it counted inquiries. The original FICO 08 formula dinged credit seekers less than the classic FICO score for opening new accounts, based on research that inquiries had become less predictive of defaults over time. Interestingly, the relationship between inquiries and defaults reestablished itself in subsequent months, so the current FICO 08 formula treats them much the same way the classic FICO does.

Because of this and other delays, FICO 08 fell behind schedule. Fair Isaac now expects the credit bureaus to begin offering the score to lenders starting in early 2009.

There’s no telling whether, or how quickly, FICO 08 will supplant the classic FICO score. Fair Isaac’s previous major attempt to improve on the FICO, a scoring formula called NextGen, fell flat—in part because NextGen relied on a 150-to-950 scale that would have required lenders to revamp their underwriting systems and software—major modifications in which few companies wanted to invest.

FICO 08, however, retains classic FICO’s 300-to-850 scale and its “reason codes”—specific explanations of why the score is what it is. That means lenders have to go to much less effort to switch, which may improve its chances of adoption.

Fortunately, all the strategies I outline in Chapter 4 for improving your score work with both iterations of the FICO score. To better understand the nuances of the change, however, read the following scenarios Fair Isaac created to demonstrate how FICO 08 works.