The three major credit bureaus—Experian, Equifax, and TransUnion—made a big splash in March 2006 when they announced a new credit-scoring system called VantageScore. In an unprecedented move, the three competing bureaus worked together to create a scoring system to rival the entrenched FICO.

Using words such as innovative, consistent, and accurate, the bureaus strongly implied that they had created a better mousetrap.

Many media outlets picked up the hype, proclaiming that VantageScores were an improvement on the FICO scores that most lenders use. Articles and broadcasts proclaimed the new credit score was “great news for consumers,” that it would “simplify” or “remake” the credit application process. One columnist even proclaimed, with little apparent evidence, that “creditworthy people...are more likely to get credit now.”

People who know about credit scoring took a decidedly more “wait and see” attitude. So far, VantageScore has not managed to push FICO off its perch as the leading credit score.

We discuss the reasons for this later in the chapter. For right now, let’s discuss the nuts and bolts of VantageScore.

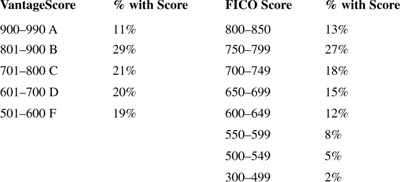

Whereas the classic FICO score ranges from 300 to 850, the VantageScore runs from 501 to 990. To make the score more “intuitive,” the bureaus designed each tier to correspond to the alphabetic grading system that most of us know from elementary school:

901–990 equals A credit

801–900 equals B credit

701–800 equals C credit

601–700 equals D credit

501–600 equals F credit

At the time the bureaus announced the VantageScore, they released statistics showing the percentage of population with each “grade.” Put those statistics next to similar statistics supplied by Fair Isaac for FICO scores, and you’ll soon notice something interesting.

The two scoring systems manage to put similar percentages of people in their highest three tiers. The FICO scale offers more tiers at the lower end than VantageScore, but the percentage of folks in the basement appears roughly the same.

Under the VantageScore system, 19 percent of borrowers have F credit. If you use a FICO score of 620 as a cutoff point for subprime credit, which many lenders do, you get similar results: Fair Isaac says that 19 percent of consumers have FICO scores below 620.

The bureaus and Fair Isaac caution against drawing conclusions from this comparison about where any consumer might stand in one system versus the other. But it does appear possible that some people who would rate a good score from Fair Isaac—say, in the low 700s—might wind up getting a C rating from VantageScore.

The only way to know where you stand, of course, is to get your VantageScore. As of this writing, Experian was offering its version of the VantageScore for $5.95 on its Web site. The other two bureaus had plans to follow suit.

Like FICO scores, VantageScores are calculated using the information in your credit reports. The factors considered are similar—your payment history, your balances, your credit limits, how long you’ve had credit, how recently you’ve applied for credit, and the mix of credit accounts in your file.

As you’ll see, though, VantageScore divides these factors somewhat differently than FICO and doesn’t give all of them the same definitions or weights.

The following factors influence a VantageScore:

• Payment history: 32 percent—Whether your payments are satisfactory, delinquent, or derogatory

• Utilization: 23 percent—The percentage of credit that you have used or that you owe on your accounts

• Balances: 15 percent—The amount of recently reported balances, both current and delinquent

• Depth of credit: 13 percent—The length of your credit history and the types of credit you have

• Recent credit: 10 percent—The number of recently opened accounts and credit inquiries

• Available credit: 7 percent—The amount of available credit on all your accounts

If you compare that breakdown to FICO, you’ll see that both systems devote roughly one-third of the score (35 percent for FICO, 32 percent for VantageScore) to payment history and 10 percent to how recently you last applied for credit.

But here the systems diverge. FICO devotes a full quarter of its score to the length of your credit history and your mix of credit, factors that make up just 13 percent of the VantageScore.

Nearly half the VantageScore—45 percent—is made up of factors that take into account how much credit you have and how much you’re using, something that comprises 30 percent of your FICO score.

So it’s reasonable to expect that the same action—applying for a loan, opening or closing a bank account, paying down a debt—might affect your scores under the two systems in different ways.

We already know that the same action can have dissimilar effects on people’s FICO scores, depending on their particular credit situations and the information in their files. Someone who has excellent credit, for example, typically loses many more points by making a late payment than someone who already has a lot of delinquencies on his reports.

But there’s some evidence that the same action can affect a person’s VantageScore differently than his FICO.

For instance, Fair Isaac says it’s relatively rare for a new credit account to boost a FICO or even leave it unchanged. Typically, new accounts reduce a FICO by at least a few points, and sometime more.

Illustrations provided by Experian’s VantageScore site, however, show applications for credit significantly increasing scores for some borrowers.

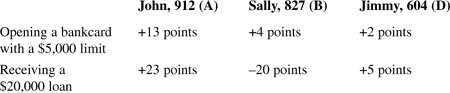

Experian created three fictional borrowers with different scores and then showed the effects of applying for a credit card and a $20,000 loan.

Credit Actions and Their Effect on VantageScores

John, the A credit borrower, benefits the most from opening new credit and suffers the least from closing an account. The $20,000 loan that adds significantly to his score would, by contrast, shave 20 points from Sally’s. Jimmy, the D scorer, gets a boost from either type of loan, but the benefit is just a few points.

At the time of this writing, Experian didn’t have a simulator that would allow consumers to see how such actions would impact their individual VantageScores, so I couldn’t tell how opening a credit card account or a car loan would affect my own score.

I was, however, able to use MyFico’s credit score simulator to see what impact the same actions would have on my FICO. I used my Experian FICO, which at the time was 810, or in the top 2 percent of the U.S. population. (On Experian’s VantageScore scale, I rated at the top of the A students, with a score of 990; Experian says only about 1 percent of the population scores that high.)

As you’ll see, my answers were somewhat different from those experienced by John with the A rating from VantageScore.

(I need to add here that a major problem with MyFico’s score simulator is that it isn’t specific. It gives you a range of possible impacts on your score, and as you’ll see, the range often isn’t that helpful.)

When I asked what my score would be after opening a $5,000 bankcard, for example, the MyFico.com simulator gave me a range of 800 to 820. In other words, such an action could depress my FICO as much as 10 points—or it could boost it by 10. That’s a pretty big difference. (If the new card did increase my score by 10 points, that would be a 1.2 percent increase—similar to the 1.4 percent increase John experienced in the VantageScore illustration.)

My taking out a $20,000 auto loan would result in a score of 780 to 810, according to the MyFico simulator. So I could lose up to 30 points, or my score could be unaffected. Either way, it’s not the 2.2 percent improvement John experienced in the VantageScore illustration.

The simulators do tell us enough to make some things clear, such as the fact that late payments under either system injure everyone’s scores, and those with the best scores have the most to lose.

Failing to pay a bankcard one month—in other words, a 30-day late—would cost the D-scoring consumer, Jimmy, 13 points, or 2.2 percent of his score.

The same 30-day late would whack 109 points from B-scorer Sally’s numbers, a 13.2 percent drop. John would suffer a 176-point drop, losing nearly 20 percent of his once-admirable score.

Likewise, paying down debt, particularly credit cards and other revolving accounts such as home equity lines of credit, tends to help everybody’s score. But the better your score, the more you may have to pay to boost your numbers.

To increase his score by 10 points, John would need to pay down his $5,498 bankcard balance by $1,300. To achieve a similar 10-point improvement, Sally would need to reduce her $450 retail card balance by just $190.

Closing a bankcard account, meanwhile, injured all three fictional characters’ scores by different amounts.

As time passes, we may learn more about how VantageScore works and how it compares with the FICO. For now, though, we know at least some of the basic rules are the same between the systems. Here’s how to protect and improve your score:

• Pay bills on time.

• Pay down your debt.

• Don’t close accounts.

When VantageScore was first announced, many credit experts predicted the new system would have a tough time unseating the classic FICO score.

FICO scoring systems are deeply embedded in the complex, highly automated formulas that lenders use to evaluate current and potential borrowers. Switching to a new scoring system can be quite expensive and difficult. Credit expert John Ulzheimer, who has worked for both Equifax and Fair Isaac, put it this way: “It’s kind of like spending $10,000 to replace a $1 part, and the $1 part isn’t even broken.”

Moreover, most loans today are bundled up and sold to investors in a process that Wall Street calls securitization. FICO scores are used to evaluate and price these investments. Wall Street is quite comfortable that FICO-scored loans will behave as forecast. A new scoring system would have to prove itself at least as reliable, if not more so, to justify a switch.

Nomura Securities analyst Mark Adelson pointed out that rating agencies such as Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s also would have to retool their systems to accept VantageScores, as would major mortgage buyers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. “Unless and until that happens,” he wrote, “we expect VantageScore to raise only a trifling challenge to FICO’s dominance.”

The barriers are so high, in fact, that Fair Isaac itself has had a tough time getting lenders, underwriters, and rating agencies to switch from FICO. Fair Isaac’s NextGen, Ulzheimer said, is “demonstrably better” than the classic FICO—more predictive and better able to separate good risks from bad ones—but it hasn’t been as widely accepted as Fair Isaac had hoped because switching scoring systems is such a tall order.

Of course, the bureaus have a strong incentive to win over lenders and rating agencies: money.

Every time a bureau generates a FICO score for a lender, the bureau has to pay a fee to Fair Isaac. It’s a profitable business for the company: According to Merrill Lynch analyst Edward Maguire, credit scoring accounts for 20 percent of Fair Isaac’s revenues, but 65 percent of its operating profits.

By creating and selling their own scoring system, the bureaus cut out the middleman.

The bureaus individually have tried to break Fair Isaac’s grip on the credit-scoring market before without much success. They’re hoping this joint effort—which promises a FICO-like consistent scoring formula across all three bureaus—will win over lenders who were reluctant to buy bureaus’ previous efforts to create proprietary scores.

A side note here: In unveiling the VantageScore, the bureaus made a big deal about its consistency. They touted the fact that their formula could take into account the different ways that the bureaus reported various bits of credit information and deliver scores that were consistent and comparable across all three agencies.

That caused some in the media to conclude that the FICO methodology is somehow different at each bureau. In fact, consistency has long been the FICO’s trademark. It, too, uses the same formula across all three bureaus, with minor tweaks designed to accommodate the reporting differences at each agency.

Most of the variation in consumers’ scores among the three bureaus is caused by differences in the underlying data. You might have accounts reported at one bureau that don’t show up at the other two, or you might have successfully disputed an error at two of the bureaus that still shows up at the third. Neither the FICO nor the VantageScore fixes that problem; it’s still the information on each bureau’s credit report—accurate or not—that’s used to calculate the scores.

The bureaus say they built VantageScore from the ground up, using their own expertise and databases. When announcing the new scoring system, the bureaus were careful not to compare it directly to the FICO score. In fact, when asked, bureau spokespeople said the VantageScore formula hadn’t been tested head to head with the FICO.

If the VantageScore is, in fact, better at predicting who will default—which is, of course, the whole reason for credit scores—it might be true that some folks who’ve unfairly been labeled as deadbeats would have better access to credit if lenders adopt the VantageScore. But it might also be true that those who have been getting fairly good rates and terms would be scored more harshly by the VantageScore system and find it harder to get credit.

If the score’s marketing materials are any gauge, it’s the latter result that the bureaus seem to be pushing. VantageScore is being marketed to lenders as being a better way “to classify more bad accounts into the worst-scoring ranges.”

But again, at this point it’s too early to tell how well VantageScore will do in the marketplace. We’ll just have to wait and see.