Chapter One. Introduction

Over the past 20 years, I’ve worked in various roles as an artist, from traditional designer and illustrator to jobs in all disciplines of 3D production. Only one area has been more rewarding to me than digital modeling, and that is teaching.

The information in this book is an accumulation of what I have learned during my career, and now I would like to share it with you. From understanding your role as a modeler in a production pipeline, to learning professional modeling methods and practices, to getting a job and much more, this book gives you the essential tools a digital modeler needs to work in the 3D industry.

I encourage you to read every page to fully benefit from this book’s contents and hope it serves you well in your own career as an artist.

What Is Digital Modeling?

You’ve probably picked up this book with some understanding of what digital modeling means, but to make sure we’re on the same page I thought I’d start off by defining it.

Digital modeling refers to the process of creating a mathematical representation of a three-dimensional shape of an object.

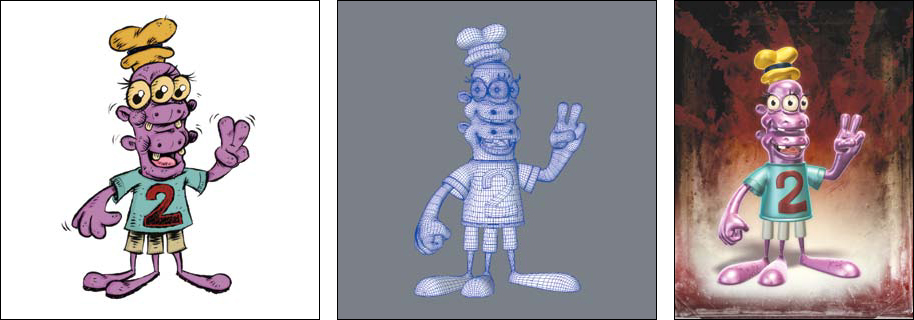

The result of this creation is what the industry calls a 3D model or 3D mesh. The 3D model of the character Tralfazz (from the indie comic series, Patchkey Kidz) went through the digital modeling process by starting as a 2D concept drawing, shown on the left in Figure 1.1. I created a 3D digital model of the character (center) and finished with a final 3D rendered image for print (right).

[Figure 1.1] Tralfazz 2D concept art created by Chris Patchell (left). A wireframe mesh is generated (center) and a final 3D render is made (right).

In the simplest of terms, digital modeling is 3D modeling.

You can create 3D models manually or automatically. The most common sources of digital models are those generated by an artist or technician using 3D software, as well as meshes that have been scanned into a computer from real-world physical objects using specialized hardware.

Digital modeling is an important component of any 3D production and is, hands down, my favorite aspect of a production pipeline. Throughout this book I explore various techniques and practices to generate a wide range of digital models.

Who Can Become a Professional Digital Modeler?

The fact that you are holding this book is a good sign that you can go on to be a successful digital modeler. You are already either taking steps to explore the world of modeling or to expand your current knowledge as a digital modeler.

Once limited to careers in the science and entertainment markets, digital modelers have more opportunities now than ever before. The demand for high-quality 3D graphics and animation is on the rise, and according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) the job market for 3D artists is expected to grow at a rate of 12 percent through 2018 (www.bls.gov).

You see 3D graphics literally everywhere these days, and at their core are digital models. Digital modelers work in television and feature films, game design, medical illustration and animation, print graphics, product and architectural visualization, and many other markets that make up this growing field. I’ve had my fingers in a lot of these markets over the years, and it has been interesting to see that I can use the same core skills for all of them. The subject matter and delivery method may change, but the fundamental toolset remains the same. The 3D models used in Figure 1.2 (on the following page) are just a few examples of how digital models are being used today.

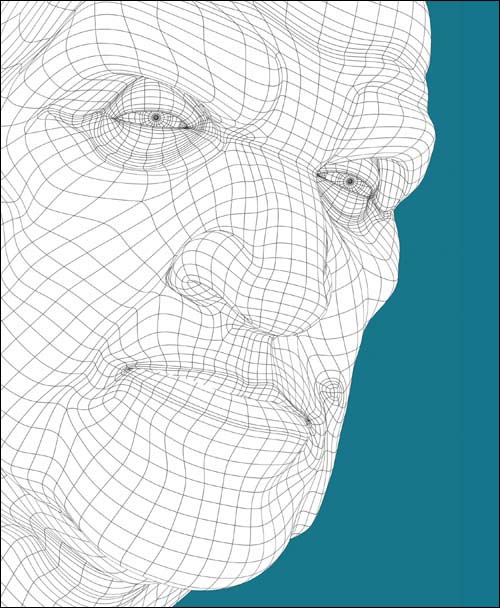

[Figure 1.2] Four examples of 3D models.

To be successful in this field, you need to become a problem solver with good observation skills and a desire to create things. You never stop learning in this field. You face new challenges with every new project, many of which require innovative solutions that you must discover on your own. If you get to a point where you stop seeing these challenges as lessons that help build your ever-growing skill set, it’s probably a sign that you’ve lost your passion for the medium and it may be time to explore other career options.

I’ve been teaching digital art almost as long as I have been creating it. When it comes to generating digital models, I’ve been asked just about every question there is. What kind of hardware to use, which specific techniques I apply to my model making, what to do about erratic sleeping habits, what kind of music I listen to, and just about anything else you can think of. But the most common question I’ve been asked by people interested in this industry is, “Can I become a digital artist?”

“To follow, without halt, one aim: There’s the secret of success.”

—ANNA PAVLOVA

My response is always, without reservation, yes! I don’t even need to know anything about the person asking, either. At the risk of sounding like Bob Ross or Mister Rogers, I always say that you can be anything you want to be as long as you have a passion for it and are willing to roll up your sleeves and put in the time to gain the skills needed to succeed.

I’ve trained students with a wide range of backgrounds and skill sets. Some started with more experience than their peers, which enabled them to work on major productions rather quickly. I’ve also instructed students with little to no experience in computer graphics (CG) who, despite their limitations, still managed to create a career in the industry by applying themselves. A few years ago I instructed a student who worked as a janitor at a Florida high school and had a passion for movies. That passion drove him to focus on building his skill set to allow him to pursue his lifelong dream of working on feature films. He’s now happily working in California with several movie credits under his belt (I recently spotted his name in the credits of Marvel’s Thor and Captain America).

Remember that talent is only one very small part of the equation and counts for nothing if it isn’t backed up by perseverance, determination, resilience, and practice. If you want to be good at anything, learn as much as you can and work at it every day until you’ve mastered it.

So, in short, you can become a professional digital modeler.

Who Should Read This Book?

Those interested in expanding their knowledge in the creation of professional, production-ready, digital models—including but not limited to modelers, animators, texture artists, and technical directors—can benefit from the valuable information covered in this book.

• A professional 3D modeler wanting to enhance your problem-solving skills and explore alternate modeling techniques.

• A professional technical director, texture artist, or animator interested in other areas of the production pipeline and in using knowledge of digital modeling to enhance your current workflow.

• An instructor looking for new ways to teach aspects of digital modeling and its role in the industry.

• A student of CG looking to improve the artistic quality of your work and to learn about professional approaches to modeling before entering the industry.

• A hobbyist interested in real-world production techniques and strategies.

As with the entire series of [digital] books from New Riders, this book is written to be clear, not condescending, and to act as a reference and guide to contribute to the ongoing growth of your work.

What Can You Expect from This Book?

Although this book focuses on the art and science of digital modeling, it doesn’t turn a blind eye to the other roles in an animation or visual effects production pipeline. It is my intention not only to share with you valuable production-proven modeling techniques and ideologies, but also to prepare you for a successful career as a digital artist.

This book is far from a rehash of information found in your 3D software’s manuals and Help files. It’s a compendium designed to complement your current skill set. You’ll learn

• The modeler’s role in a production pipeline

• How to prepare for a modeling session

• The fundamentals of digital modeling

• Multiple modeling techniques

• How to land a job in the industry

• And much more

What You Should Know

For me to focus on the core attributes of what makes for efficient production-ready models and how to achieve them, I’ve made some assumptions on your skill level in a few areas. I’m assuming you have a fundamental understanding of Mac and/or Windows computers, including basic file structure protocol, working with peripherals, using Internet search engines, and using portable storage drives.

You should have a working knowledge of at least one 2D paint and one 3D graphics program of your choice, basic experience with 3D digital modeling, and a fundamental understanding of 3D space. It’s important to remember that this book is not designed to replace your softwares’ manuals and Help files. Whenever you need to use those, do so.

You don’t have to have a working knowledge of every application used in this book. I cover the topics in a way that allows you to apply them to modeling in any 3D software.

I can’t think of a single 3D modeling application that supports every feature or function covered in this guide; so the more comfortable you are with the software you are using, the easier it will be for you to translate any tool-specific process to the tools available in your application of choice.

Don’t be discouraged if you feel that you don’t currently have the knowledge required to continue. In this digital age you can easily get up to speed by doing some research on the Internet.

What You Will Need

Although I spend a great deal of time in this book focusing on the fundamentals of 3D modeling, some sections use a project-based approach to cover specific principles and techniques. The easiest way to absorb this material and commit it to muscle memory is to roll up your sleeves and actually do the projects as you read. So, you will definitely want to have a computer and the necessary software to get the most out of this book.

Most 3D modeling applications come in versions for both Mac and Windows, so whatever type of system you prefer, you should have no problem as a digital modeler. If you are buying a computer, make sure that its specifications are up to the requirements of the software you want to run. Don’t feel like you have to run out and get the latest and greatest monster machine, as many may suggest. You might be surprised at how a modest system configuration can be all you need to work comfortably. That said, the more powerful the system, the more you can throw at it.

RAM

Random access memory (RAM) is where the data set you are currently working with resides in your computer. This data can be in the form of images or 3D point data, such as models. The more RAM you have, the more data you can simultaneously access without having to wait for the system to load it from the hard disk. Loading from the hard disk is slow.

CPU Speed and Number of Cores

With today’s multi-core CPUs, computer processor speed is becoming less and less important. The more cores you have, the better off you are, so CPU speed is to be considered in relation to how many cores your computer has. Simply put, speed and number of cores are the main features that make rendering and data processing faster.

Graphics Card and GPU

A decent graphics card is an important factor for digital modelers, because it’s responsible for displaying your data onscreen. Because most applications use OpenGL (Open Graphics Library)—the industry-standard Application Programming Interface (API) for writing applications that produce 2D and 3D computer graphics—a strong graphics card allows you to view your digital models as smoothly as possible.

The more geometry or hi-res (high-resolution) textures, the harder your graphics card has to work. Having a good graphics card definitely increases productivity as projects become more complex. NVIDIA is a graphics card industry leader and has the most stable platform for the CG industry.

Another factor to consider is Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) technology. The industry is starting to make a shift towards GPU-based rendering, essentially harnessing the power of the graphics card, which often is 50–100 times more powerful than a CPU for performing certain tasks. When choosing a graphics card, it’s best to consider the amount of GPU cores it has; the more, the better.

If you’re unsure of what type of system is best for you, visit one of the many online community forums—for example, CGSociety (www.cgsociety.org), 3DTotal (www.3dtotal.com), or Foundation 3D (www.foundation3d.com)—talk to artists who use these systems, research what’s available, and most importantly, know your options.

Two Monitors

Something I have strong opinions about when discussing workstations is the need for a dual monitor setup. I believe dual monitors are a must for any digital artist and can’t imagine accomplishing my work using just one monitor. That doesn’t mean you have to invest in the largest, most expensive monitors available. For years I used two modestly priced 19-inch Viewsonic monitors that would satisfy even a tight budget.

Several extremely nice wide-screen monitors are available today that some might argue are just as good as using two monitors, but in my opinion, if you go that route, you might as well get two of them. Most studios I’ve visited have multiple monitors for their artists (Figure 1.3).

[Figure 1.3] Digital artists at BranitFX take advantage of multiple monitors while working on television shows like Breaking Bad, Californication, and Fringe.

A digital modeler working with just one monitor is like a draftsman working on an end table instead of a large drafting table. Having two monitors gives you more than just a comfortable workspace—it affords you the room needed to display multiple applications at the same time, as well as the ability to display your reference material on one screen while you work on the other.

About This Book’s Approach to Software

Every working artist in CG has a preferred modeling application when generating meshes. I’m willing to bet that if you randomly asked professional artists throughout the industry which tools they use when they create, you would find a distinctive mix of software that each swears by. Usually, it’s the software that they either started out using when they were learning about CG, or it’s the software in which they have the most experience in. This makes perfect sense, but it has created something known as software wars.

Software wars are as old as the software applications, and as far as I’m concerned, arguing about them is a complete waste of time. Don’t even bother getting into a debate with someone over which software is the best; you’ll only exhaust yourself justifying why your software of choice is “better.” No matter what is said during this argument, it is very likely that each of you will leave the conversation convinced that you are still using “the best” software.

Have you ever heard the phrase, “It’s not the tool, it’s the craftsman (or craftswoman)”?

Take a few minutes to explore any 3D software’s online gallery, and you’ll see breathtaking work being created. Whether the software is free, cheap, or super expensive, artists are creating amazing pieces of art with it. Don’t get too caught up in software, because throughout your career as a digital artist you will most likely use various modeling and sculpting applications. Each comes with its own workflow, but the core fundamentals of modeling stay the same. That principle guides my approach to software in this book.

One of the main aspects of the [digital] series that attracted me to writing this book is that it doesn’t focus on using any specific software. Hence, my book teaches you essential skills and concepts that you can apply to modeling in any 3D software.

Whatever software you own or decide to buy, be sure to read the manual. You need to become familiar with its tools and how that particular software works. You can use [digital] Modeling to help you generate professional meshes with those tools.

The bottom line is this: With some creative problem solving and an understanding of your toolset, you can accomplish anything you set out to create using any modeling application.

Software Requirements

Note that most applications have 30-day trial versions available on their Web sites. Also, several open source 3D applications, such as Blender (www.blender.org), are quite capable and absolutely free. A 2D paint and image manipulation application is also recommended.

3D Software

Although this book is software agnostic, I’ll mention particular modeling packages throughout, because not every application supports the wide range of features and functions covered. However, most areas of this book describe several alternate techniques to achieve a given effect, so you can accomplish tasks no matter which program you use. Leading 3D software programs I mention include

• 3ds Max: www.autodesk.com/3ds-Max

• LightWave 3D: www.lightwave3d.com

• Maya: www.autodesk.com/Maya

• Modo: www.luxology.com

• Silo: www.nevercenter.com

• XSI: www.autodesk.com/Softimage

• ZBrush: www.pixologic.com

2D software

A 2D paint and image manipulation application should be part of any digital modeler’s toolkit to create and manipulate reference material and to generate texture maps. Adobe Photoshop (www.adobe.com) is the industry standard, but if you can’t afford it, remember that there are a wide range of options available today, such as

• Paint Shop Pro: www.corel.com

• GIMP: www.gimp.org

• Paint.net: www.getpaint.net

Many other applications are available, too, that work perfectly fine.

What’s on the Disc

Over six hours of training videos are included on the accompanying DVD and support the topics covered in this book. Although the examples in the videos use NewTek’s LightWave 3D and Pixologic’s ZBrush, the information covered can be easily translated to any 3D software. There are 18 videos that explore a wide range of modeling tools and techniques and 3 videos located in the ZBrush directory that show the entire sculpting process of the creature maquette in Chapter 12. I recommend viewing these videos once you have finished reading the book to fully benefit from the information covered. In addition to the training videos, I’ve included a video that shows 100 character models and their topology that can be used as inspiration and reference to study poly flow.

Some of the images printed in the book contain fine lines in the 3D program that may not show up clearly on the printed page. You’ll find high-res versions of the images from the book on the disc, allowing you to see more detail.

Mentioned throughout the book is the Tofu the Vegan Zombie award-winning animated short, Zombie Dearest. This short can also be found on the disc so grab some popcorn and enjoy.

A Final Word: Change Your Thinking

Now that the formalities are out of the way, we’re almost ready to get to the meat of this book. But first I want to cover a topic that is extremely important to your success.

When I start teaching someone about digital modeling, I usually find myself having the same conversations I’ve had a thousand times regardless of whether the artist I’m talking to has zero experience or is working in the industry. They all have the same desire to succeed, but in each of their paths to 3D mastery one thing stands in their way. Once they get past this roadblock, it’s all smooth going.

What is this “one” thing that you have to get past (or passed, if you are a student of mine)? Could it be Booleans? Polygon flow? Radiosity? A corn-free diet?

The answer is none of those things, although the corn-free diet makes for a creative answer. Actually, the one thing you need to get past is simply the way you think.

It’s my experience that most people have a can’t-do attitude, especially when it comes to learning new things. When I say most people, I’m not limiting that to artists new to 3D. I witness this on just about every forum online and at the industry shows I attend. Most people assume that things are not possible, they are too difficult, or special software/hardware is needed to solve the problem. I always suggest a different approach.

It may sound cliché, but the power of positive thinking goes a long way when working in this industry. Every day you’ll be asked to tackle the impossible, and if you go in with the attitude of can do, you’ll be able to see the task to completion. If your attitude is not possible, you will most likely not complete the task. It’s called a self-fulfilling prophecy. Robert K. Merton, the man who is credited with coming up with the expression, explains it this way:

“The self-fulfilling prophecy is, in the beginning, a false definition of the situation evoking a new behavior, which makes the original false conception come ‘true.’ This specious validity of the self-fulfilling prophecy perpetuates a reign of error. For the prophet will cite the actual course of events as proof that he was right from the very beginning.”

Simply put, go into every new venture with a positive attitude, and you will be able to accomplish things you never knew you could. I get asked to do something I’ve never done all the time, so I always go in with the idea that I will be able to do it and will have that much more experience when it’s done. Accept the fact that you haven’t done that task, but don’t dwell on it.

I always tell people, “I know everything I need to know to do the things I’ve already done.”

Even I have to admit that it sounds silly but it’s a great way to approach each new task. Really give thought to that statement. The next time you feel like giving up before you even begin, recite that phrase. Say it out loud if you have to. It’s very similar to one of my favorite quotes from René Descartes, which states, “Each problem that I solved became a rule which served afterwards to solve other problems.” In this industry, we are not modelers, lighters, animators, or compositors. The best title for what our job is on a daily basis is problem solvers. As production artists, we are thrown problem after problem, and we have to devise solutions to move on to the next phase in production. Then when you wonder if something is possible, say, “I bet it is; I just need to figure out how to do it.” Do that and I believe you’ll have far better results than giving up before you begin.

One of the biggest hurdles for new users to overcome when problem solving is actually trying to use the tools currently available instead of wishing for the tools of tomorrow. I once had a student who wasn’t producing tell me that he couldn’t complete his tasks because he was waiting for technology to catch up with his ideas. He left me speechless! To this day he is still waiting for those magical tools to catch up with his unrealized ideas, whereas others who have the right attitude are realizing even better ones. Maybe I’ll check back with him in a few years to see if the tools he was waiting for were ever released and see if he has any of those incredible ideas left to realize.

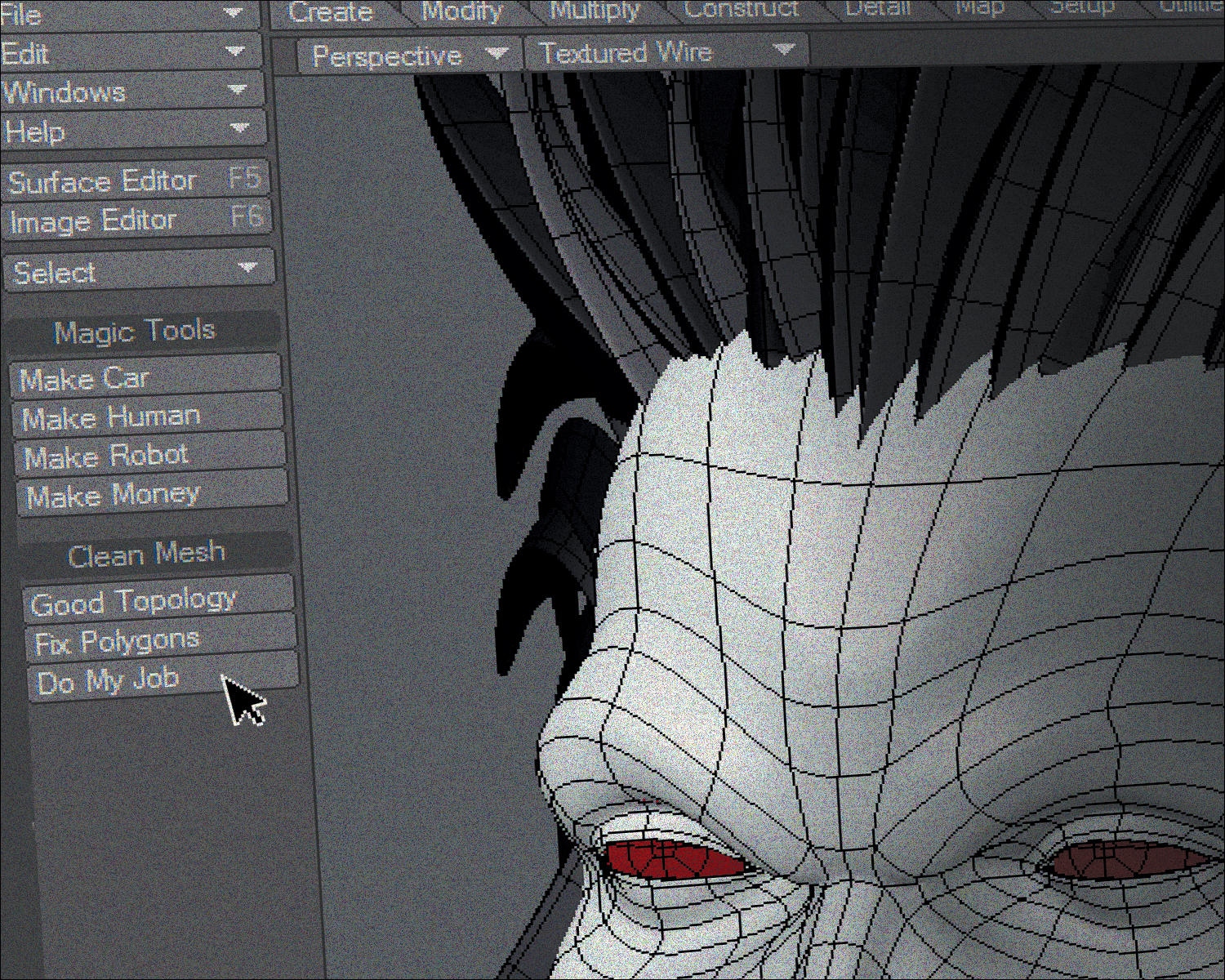

I like to call this magical tool the Do My Job button. You know, the button that you click and it creates whatever you’re currently tasked with in one simple step (Figure 1.4). Many people waste valuable time looking for the “easy” way out of their problem. Although this method sometimes leads to a breakthrough, usually the end result is lost time. The sooner you realize there isn’t a Do My Job button and that you need to put a little elbow grease into each project, the sooner you will be on your way to producing amazing work.

[Figure 1.4] Although many artists search for these buttons in their 3D software, they’ve yet to find them.

I tend to use the phrase “back in the day” all the time—which is surely a sign of getting older—yet I can’t help but explain to new artists the stuff we used to have to do to solve what seem like minor hurdles with today’s tools. Not having the tools didn’t stop us. When we needed a flag blowing in the wind and there were no cloth dynamics to be found, we simply ran a procedural texture through a segmented plane and called it a day, and at the end of the day (to use another overused phrase) what it is really about is solving each task with the tools and techniques that you currently have. Sure, the tools will improve and so will your bag of tricks, but you already have the things you need to accomplish today—not tomorrow!

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying don’t push for new tools and improvements from the software developers. I push for new tools all the time. What I don’t do is let the tools I currently have in hand stop me. This type of positive thinking and problem solving is what has helped most successful artists and studios flourish. Otherwise, studios with massive teams of programmers to write every tool needed for every job would be the only ones playing a significant role in our industry. What fun would that be?

It probably says a lot about me, but I usually give software programmers the benefit of the doubt and assume I’ve made a mistake when something goes wrong. It saves me a massive amount of time as I start trying to work through the problem as soon as it pops up. Here is a trick that has worked for me over the years and seems to be working for many artists working in the industry today. The next time you’re deep in production, and the software crashes or doesn’t give you the result you’re after, ask yourself, “What did I do wrong?” Don’t assume it is a bug in the software or blame the computer, even if it turns out that it is.

I’ve found that 98 percent of the time the problem turns out to be user error. If your first thought is that it’s the software or hardware, you have already come to a conclusion without working through the problem. Before you blurt out the knee-jerk reaction of “I didn’t do it!” ask yourself, “What did I just do?” It’s hard to take the blame sometimes, but give it a try and see if your workload becomes easier. Just remember the term PICNIC (Problem in Chair Not in Computer), and you’ll be set.

As CG artists, we need to be problem solvers who are able to think fast and tackle any issues that are thrown our way. With positive thinking and experience, nothing is impossible. These are the tools that allow us to create lovable characters, amazing explosions, and photo-real environments. It’s not about the software or hardware. Software and hardware will continue to evolve, and you may find that you jump from one application to another over the course of your career. But the true value of your abilities is your problem-solving skills, not where the Boolean tool is located and what it does.

This philosophy is what has allowed me to accomplish the things that I’m most proud of, and it is my most valuable skill. Take advantage of your problem-solving skills and mix in some positive thinking, and nothing will stand in your way.

So now, let’s dive in!